1. Introduction

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, many countries have adopted drastic measures to control the spread of the virus: schools and workplaces were closed, social distancing measures were enforced, and social gatherings were prohibited. These measures, while limiting the spread of infection, had their own effects on people’s lives, from social isolation and loneliness to serious economic disruption and loss [

1]. Psychologically, such disruptions to life routines and financial security can result in increased uncertainty, ambiguity, loss of control, and economic worries, all of which are known to trigger emotional distress [

2]. A comprehensive review of the impact of quarantines during previous epidemiological events suggests that the psychological fallout of lockdowns and restrictions can include post-traumatic stress, anxiety, confusion, and anger [

3].

In general, aging is often associated with increased well-being [

4]. However, the increased mortality risk of Covid-19 for older people [

5,

6,

7] means that during the pandemic, older adults have been at particular risk of fear, anxiety, and stress compared with other age groups [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. This may be particularly true for older adults living in residential care homes, who in many countries have been barred from socializing, leaving the premises, and receiving visitors – even close family and other loved ones – for long stretches of time during the pandemic. All these factors raise the question of whether there are practices or interventions which might improve mental health outcomes for older adults residents of care homes under conditions such as the Covid-19 lockdowns.

Self-management in older adults is a construct capturing physical, social, and cognitive capacities, including initiative, self-efficacy, multifunctionality, and a positive frame of mind [

13]. The present study took advantage of a broader study on the contribution of self-management to older adults’ well-being that was underway before the onset of the pandemic. During this study, care home residents underwent 22 sessions of chair exercises – physical exercises performed while seated in a chair, designed to improve strength, balance, and mobility – based on previous work showing that physical activity improves self-management in older people. Restrictions due to the pandemic were imposed after the 22nd session, meaning that from that point residents were unable to meet for group exercises. However, some of the residents continued to perform the exercises independently. In this study, we examine the impact of self-management on psychological outcomes (including anxiety, traumatic stress symptoms, and post-traumatic growth, among others) in older adults who practiced the exercises independently during the first two months of the Covid-19 pandemic, compared with a group that underwent the training but did not continue to practice the exercises.

This paper offers two main contributions. First, we show that independent physical exercise based on individuals’ own planning and self-reflection can contribute to the improvement of aging management. Second, while many older adults suffer regularly from loneliness, there is extra value to being able to predict psychological outcomes – including the development of traumatic stress symptoms and post-traumatic growth – and to offer relevant aid during periods such as the Covid-19 pandemic, when social gatherings are banned for public health reasons.

In what follows, we first briefly review background information about Covid-19 as a traumatic event and aging management. We then introduce the present study and present our hypotheses. Following this, we describe our method and present our results. We conclude with a general discussion, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

1.1. Understanding Covid-19 as a Traumatic Event

In a recent conceptual paper, Horesh and Brown [

14] contend that the Covid-19 pandemic has had the potential to magnify societal and personal vulnerabilities and to create high levels of anticipatory anxiety. Given the expected timeline for the course of the virus, people have mainly feared the pandemic’s immediate impact on their medical and psychological well-being, but are also uncertain of their capacity to overcome its broader, long-term effects. Horesh and Brown (14) suggest that Covid-19 meets many criteria of mass traumatic events and should be viewed from that perspective, beyond people’s concern for their medical well-being.

Van der Kolk and colleagues [

15] argue that the effects of chronic interpersonal trauma extend beyond the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) described by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM, and include persistent alterations in affect regulation, consciousness, bodily processes, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships, as well as existential meaning. Indeed, a close inspection of the accumulating research on the effects of exposure to a traumatic event (or a natural disaster such as the Covid-19 pandemic) reveals broader and more comprehensive effects beyond the immediate reaction to the disaster. For example, Brown, Kallivayalil, Mendelsohn and Harvey [

16] found that in addition to recognized PTSD symptoms such as intrusive memories or being easily startled or frightened, PTSD patients also reported that their condition undermined their sense of mastery and their ability to find meaning in life. Fellman, Ritakallio, Waris, Jylkkä and Laine [

17] found that while Covid-19-related anxiety levels tended to fall over the weeks following the initial psychological “shock wave” of the pandemic, this anxiety had a strong disruptive effect on cognition which continued over time (see also Helton et al., [

18]). In another recent study, young adults facing Covid-19 reported feeling uncertainty about their lives and concern about their capacity to achieve their aspirations in the future [

19].

Considering the scale of the pandemic’s psychological effects, it is important to identify factors that can help individuals retain a sense of control, live with uncertainty, and find meaning in life. In this respect, discussing ways of working with trauma patients, Brown and colleagues [

16] argue that it is imperative for therapists to be attentive not only to the client’s psychopathology, but also to the client’s strengths and capacity for recovery.

1.2. Self-management

Self-management is an aspect of aging management [

20] - a relatively novel term that emerged from within the theory of active aging [

21,

22]. According to this theory, older adults individuals can maintain positive well-being through a combination of physical, social, educational, and cultural activities [

23,

24]. In particular, previous work has shown that physical activity improves autonomy and reduces dependence among older adults [

25]. Being active helps keep the individual emotionally and mentally fit [

26], whereas passivity leads to loneliness and social isolation [

27], and to negative emotions such as unhappiness and depression [

28].

From a resource perspective, successful aging requires the proactive management of resources [

29]. Self-management enables the individual to use internal resources, such as initiative, self-efficacy, or a positive frame of mind [

13], to manage external resources (e.g., food, friends, family) in such a way that physical and social well-being are maintained or restored [

30]. Even when resources are declining, for instance in the wake of illness or other major life events, successful management ensures the availability of reserve capacities to realize and sustain physical and social well-being [

31]. Findings have shown associations between self-management among older adults and reduced loneliness [

32,

33,

34], increased well-being [

29,

35,

36], and the prevention of falls [

37].

1.3. Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic on older adults

Since the start of the outbreak, most mortality from Covid-19 has occurred among older people [

38]. Fear of death, and awareness of their vulnerability, may lead to chronic psychological pressure for older adults [

8]. Beyond the fear of death, the social disconnection and isolation imposed by government restrictions have put older adults at greater risk of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and grief [

39,

40]. The problem is compounded for many older adults in that the senior centers and other social spaces that have traditionally been central in promoting active aging [

41] have had to close precisely when they are most needed. Under these unique conditions, self-management may become crucial for maintaining older adults’ mental health.

A number of studies have addressed problems of social care and aid for the older adults due to their unique vulnerability during the Covid-19 pandemic [

9,

42]. For example, Flores Tena [

43] argues that programs to promote active aging by encouraging active participation and healthy habits can reduce older people’s dependence during the pandemic. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet examined the association between self-management and mental health during the pandemic among older adults.

1.4. The Present Study

The present study compares psychological outcomes including traumatic stress symptoms, post-traumatic growth (PTG), anxiety, life satisfaction, and general mood among older adults who performed a set of self-directed physical exercises independently during the pandemic compared with a group that did not perform the exercises. For this research, we took advantage of a broader study on the contribution of self-management to older adults’ well-being that was underway as the pandemic began. As part of this study, care home residents in Israel provided data about their self-management in the autumn of 2019. They then underwent about six months of weekly training in chair exercises – physical exercises performed while seated in a chair, designed to engage all parts of the body and to improve strength, balance, and mobility. The initial training phase was planned to last 24 weeks, with one training session per week. Due to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and Israel’s first lockdown, the training was halted after 22 weeks, and residents were instructed to stay isolated in their apartments within the care home.

The first two months of lockdown were confusing and emotionally demanding for both residents and caregivers. Accurate information regarding the virus – its transmissibility, mortality rates, effective means of prevention, etc. – were lacking. Likewise, nobody knew how long the pandemic might last, and when restrictions on residents’ movements and social interactions would be lifted.

During this period, participants in the original self-management study were not instructed to follow any physical routine. However, some participants, of their own initiative, continued to practice the exercises on their own. This situation naturally created two study groups, one which engaged in independent self-training, and one which did not. The present study reports on psychological outcomes collected eight weeks after the pandemic’s outbreak among members of these two groups.

Based on theory and previous findings, we expected to find the following:

H1: Practicing independent self-directed physical activity will improve self-management, while not practicing will lead to a reduction in self-management.

H2: Self-management prior to the Covid-19 outbreak will be associated with psychological outcomes following the onset of the pandemic, including traumatic stress symptoms, PTG, anxiety, satisfaction, and general mood.

H3: The difference in self-management (improvement or decline) associated with practicing or not practicing self-directed physical activity will make a unique contribution to the variance in psychological outcomes following onset of the pandemic beyond initial (pre-pandemic) self-management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were part of a broader study on the contribution of self-management to the improvement of well-being among older adults living within the community and in a residential care home. The current study is based on data collected from the care home residents. Sixty four residents participated in the study (53 females, 11 males; mean age = 82.23 years, SD = 4.65, range = 70–95 years). Of the 64 participants, 11 (17.1% were married, 2 (3.1%) were single, and 51 (79.6%) were widowed. None of the participants were diagnosed during the study with Covid-19, and at the time of data collection 21.4% knew someone who had been ill with Covid-19. Most participants came from an upper middle-class background. IRB approval was obtained at the beginning of the process.

Thirty five participants (about 54.6%) practiced self-directed physical exercises independently during the first two months of the pandemic (see below), while 29 did not. Among those who practiced the exercises, 5 (about 14% of the 35) did so once a week, 7 (20%) twice a week, 6 (16%) three time a week, and 17 (48%) did so every day. For the analyses, we considered the 35 who practiced at least once per week as the self-practicing group, and the 29 who did not practice at all as the non-self-practicing group.

All participants took part in 22 sessions of training in physical exercises, one session per week, before the outbreak of the pandemic. The training comprised a set of physical exercises designed to engage the whole body while seated on a chair, and were suitable for this age group. While practicing the exercises, participants were instructed to think about their body movements, to be aware of their balance and mobility relative to previous classes, and to watch out for any emerging pains. Participants were instructed to stop any exercises that produced pain even if their range of movement had been higher in previous classes, thereby keeping their physical movements within a safe range. However, participants were strongly encouraged to push their bodies to the extent possible within that safe range.

Measurements were collected at two points. Before the beginning of the training, participants were interviewed face-to-face by members of the research team about their self-management in various areas of life. Then, eight weeks after the outbreak of the pandemic (eight months after the initial contact), participants were contacted by phone and asked about various psychological outcomes, as well as repeating the self-management measures. The complete set of questionnaires were completed within three days during the first round of data collection, and two weeks during the second round.

2.2. Measures

Anxiety was assessed using the 6-item anxiety subscale (e.g., “How often did you feel tense during the last month?”) from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [

44]. Answers were given on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety subscale was .81.

Traumatic stress symptoms were measured via a modified version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-5) [

45]. This 20-item self-report measure asks participants to indicate the extent to which they experienced each PTSD symptom on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Items correspond to the newly approved PTSD symptom criteria in the DSM–5 (e.g., “To what extent have you experienced distress when thinking about Covid-19?”). The original version was adapted so that the timeframe for experiencing each symptom was changed from “in the past month” to “since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic,” and the index event was the Covid-19 pandemic. Cronbach’s alpha in this study for the PCL-5 total score was .89.

Post-traumatic growth. An adapted version of the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) [

46] consisting of 8 items assessed growth following the Covid-19 experience (e.g., “I have learned that I have the capacities to cope with stress”). Statements were rated on a 6-point scale (0 = low to 5 = high). Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

General mood was measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [

47]. This self-reported 20-item scale evaluates negative (e.g., distressed, upset, scared) and positive (e.g., attentive, excited, strong) affect. Respondents were instructed to indicate the degree to which they had felt each emotion over the past two weeks on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Positive emotions were recoded yielding higher scale means reflecting negative general mood. Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Satisfaction with life was assessed through a 7-item measure assessing satisfaction with the individual’s social relationships and leisure activities, adapted from Zullig, Huebner, Patton, and Murray [

48]. A sample item: “How satisfied were you within the last seven days with your social relatiship” Items were rated on a scale from 1 (not satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Self-management was assessed through the Self-Management Ability Scale (SMAS) [

13]. This 30-item self-report measure captures various aspects of self-management, including initiative (“How often do you take the initiative to keep yourself busy?”), self-efficacy (“Are you capable of taking good care of yourself?”), investment in the self (“Do you ensure that you have enough interests on a regular basis?”), positive frame of mind (“How often are you able to see the positive side of the situation when something disagreeable happens?”), resources (“Do you have different ways to relax when necessary?”), and multifunctionality (“The activities I enjoy, I do together with others”). Most statements were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = very often), with some adjustment for the multifunctionality, self-efficacy, and positive frame of mind dimensions. Internal consistencies for the pre-training and post-pandemic onset measures, respectively, were as follows: initiative – α = .60, α = .88; self-efficacy – α = .86, α = .92; investment – α = .75, α = .89; positive frame of mind – α = .82, α = .76; resources – α = .73, α = .87; and multifunctionality – α = .82, α = .85. Cronbach’s alphas for the total scale were .93 and α = .95 for the pre-training and post-pandemic measures, respectively.

2.3.Data Analysis

Before testing the hypotheses, latent changes in self-management were first created using a path model. The latent factor scores were saved and imported into the SPSS analyses outlined below. A higher change score indicates an increase in self-management over time. Importantly, the correlation between pre-training self-management and the latent factor score (i.e., the change in self-management over time) is r = .00, suggesting that there is no multicollinearity between the two indices.

To examine the hypotheses, a series of regression analyses were conducted. Three control variables, namely gender, age, and personal status (married, single, or widowed), were entered in the first step. We assumed that self-management may decrease with increasing age, while being married might serve as a protective factor. Levels of self-management before the training sessions were entered in the second step. Changes in self-management between the beginning and end of the study (the latent factor scores) were entered in the second step.

3. Results

3.1. Self-practice and Its Contribution to Self-management

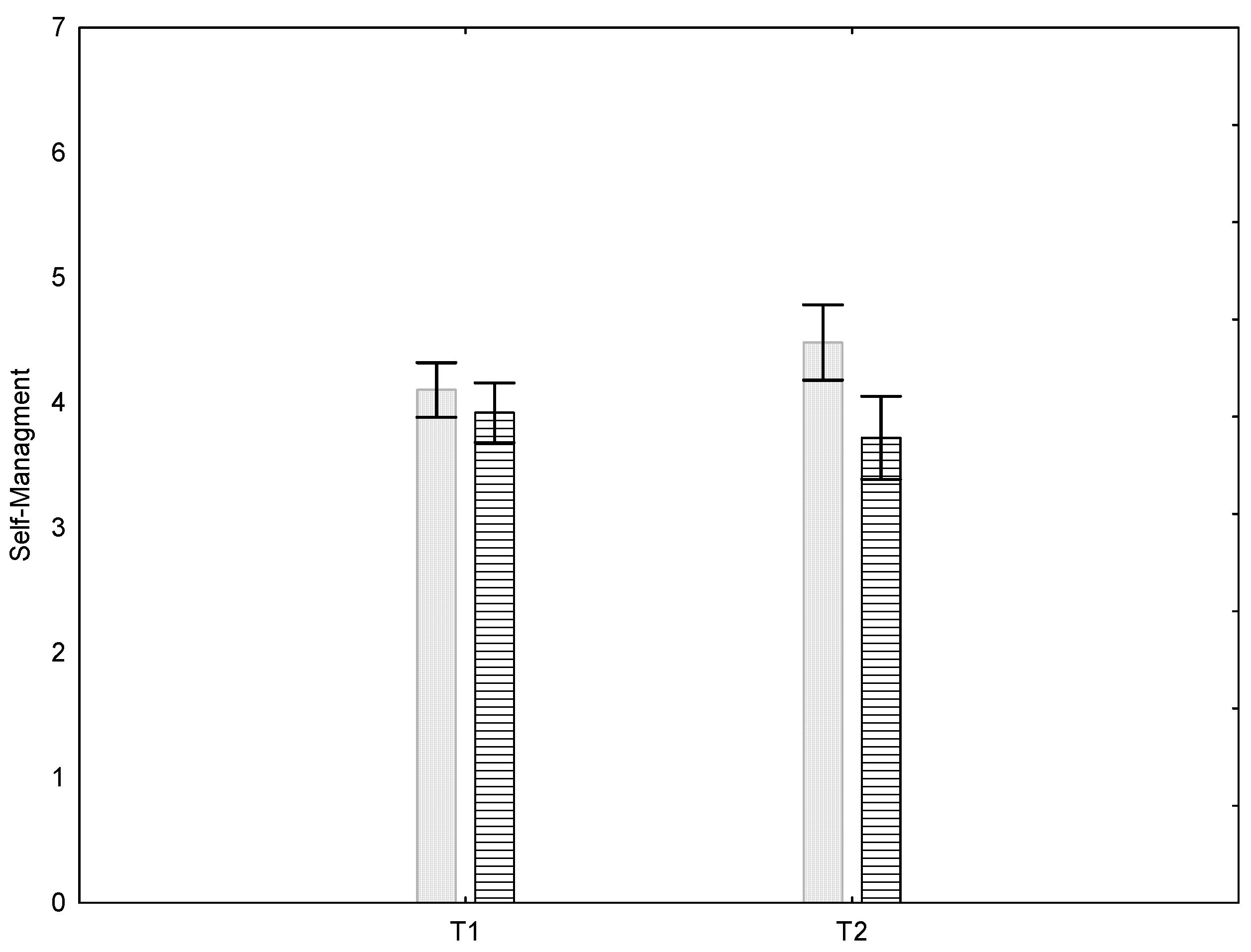

Our first hypothesis posited that practicing independent self-directed physical activity would improve participants’ self-management abilities. We first checked whether the two study groups differed in their self-management at the start of the study. We found no significant difference in self-management between the groups before the beginning of the training phase (M = 4.10, SE = .50, and M = 3.92, SE = .75, for the self-practicing and non-self-practicing groups, respectively), t(63)=1.11, n.s. However, after the outbreak of the pandemic a significant difference in self-management between the groups was found (M = 4.51, SE = .83, and M = 3.68, SE = .94, for the self-practicing and non-self-practicing groups, respectively), t(63)=3.39, p < 0.005).

To probe the data further, we used a mixed-design 2 X 2 ANOVA (self-management [pre-training or post-outbreak] X group [self-practicing: yes or no]). We treated self-management as a within-participant variable and group as a between-participants variable. Age, gender, and marital status were treated as covariates. Age and marital status were correlated at rs = .32**, with the number of widows or widowers increasing with age.

As seen in

Figure 1, the results show a significant interaction, with self-management improving in participants who independently practiced the physical exercises, and declining in participants who did not practice the exercises, F(1,59) = 5.86, p < .05, ηp² = 0.66. Thus, H1 is supported.

3.2. Self-management and Psychological Outcomes Following the Covid-19 Outbreak

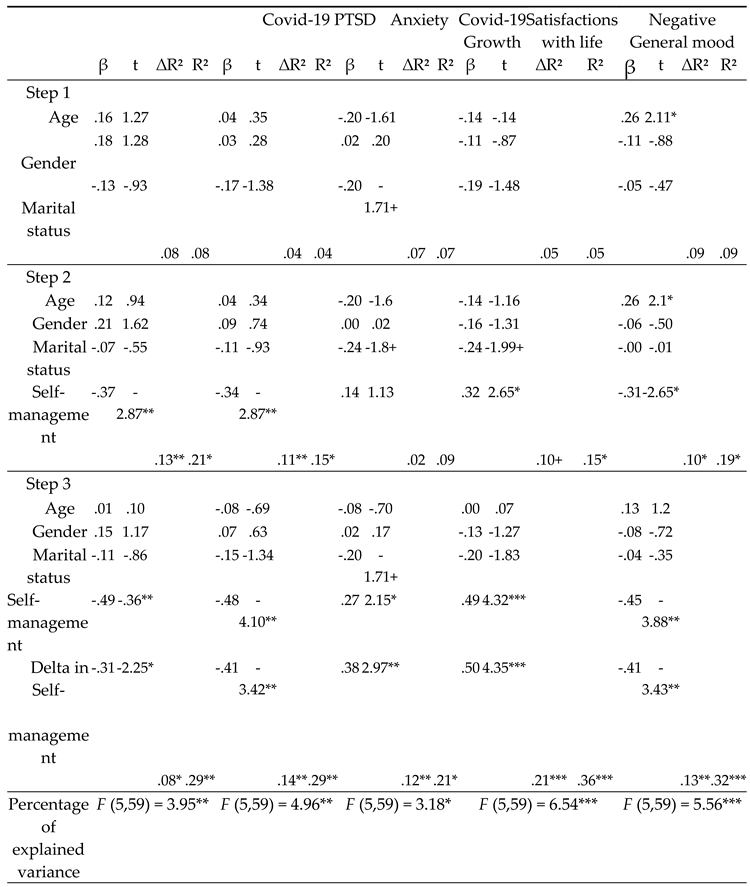

Our second and third hypotheses posited that self-management abilities prior to the Covid-19 outbreak would be associated with later psychological outcomes (H2), but that the change in self-management (improvement or decline) associated with practicing or not practicing the exercises would contribute to the variance in these outcomes beyond the effect of initial self-management abilities (H3). To test these hypotheses, we conducted three-step hierarchical regressions to capture the role of these two variables (initial self-management and change in self-management) as predictors of five outcomes: anxiety (M = 1.63, SE = .61), PTSD symptoms (M = 10.8, SE = 9.45), satisfaction with life (M = 4.76, SE = .82), general mood (M = 2.70, SE = 1.42), and PTG (M = 3.42, SE = 1.15).

As can be seen in

Table 1, except for age and negative general mood (β = .26, p = .03), there is no association between age, gender, or marital status and any of the psychological outcomes. Initial (pre-pandemic) self-management significantly predicts post-outbreak levels of anxiety (β = -.34, p = .006), PTSD symptoms (β = -.37, p = .006), satisfaction with life (β = .32, p = .010), and negative general mood (β = -.31, p = .010). Self-management does not predict PTG (β = .14, p = .26). Thus, H2 is almost wholly supported.

Our main interest is whether any change in self-management between the initial and post-outbreak measures would be associated with the psychological outcomes. As expected, we found that an increase in self-management was associated with a reduction in the negative effects of the Covid-19 outbreak, namely anxiety (β = -.41, p = .001) and PTSD symptoms (β = -.31, p = .029). Increased self-management was also associated with improved life satisfaction (β = .50, p = .000) and with changes in negative general mood (β = -.41, p = .001), as well as with an increase in PTG (β = .38, p = .004). Thus, H3 was fully supported.

4. Discussion

This study tested whether self-directed practice of physical exercises during the first eight weeks of the Covid-19 outbreak – a highly turbulent and distressing time – contributed to better self-management and, in turn, to better psychological outcomes in older adults. In line with our hypotheses, we found that pre-training self-management was a significant predictor of psychological outcomes after the onset of the pandemic, including PTSD symptoms, anxiety, general mood, and satisfaction with life. Notably, however, we also found that practicing the exercises independently was associated with improvements in self-management over the first two months of the pandemic, and that these improvements were linked with better psychological outcomes above and beyond those associated with initial self-management, including higher levels of post-traumatic growth.

Conceptualizing the Covid-19 pandemic as a traumatic event, Horesh and Brown [

14] described it as a massive attack on the world’s infrastructures and systems, magnifying functional and structural vulnerabilities, and leading to increased anxiety concerning the future. As the pandemic developed, it became clear that older adults had the highest mortality rate of any age group [

38]. For this population, the fear of death and awareness of their vulnerability was a source of chronic psychological stress [

8], while the social isolation imposed to reduce transmission of the virus put older adults at greater risk of depression and anxiety [

40]. Banerjee et al. [

42] and Cahapay [

19] stressed the need for appropriate strategies and programs to ensure the welfare of the older adults given their unique vulnerability during the pandemic. However, to the best of our knowledge, the role of self-management among older adults has not yet been studied for its protective role against the adverse psychological effects of the Covid-19 outbreak.

Our results support the theory of active aging [

22], as well as previous findings supporting the role of different activities (including physical activity) for maintaining positive well-being in older adults [

23,

24]. Fernández and Ponce de León [

27] and Petersen and Gasimova [

28] have found that passive tendencies result in loneliness, social isolation, unhappiness, and depression. Others found self-management abilities among older adults to be associated with reduced loneliness [

34] and improved well-being [

36].

Cramm et al. [

49] argued that successful aging requires the proactive management of resources. The participants in the current study, who were residents of a care home, had limited external resource during the Covid-19 pandemic, due to regulations that imposed strict isolation and social distancing among all citizens. Gatherings within the communal areas of their care home, which had previously been a big part of residents’ lives, were now prohibited. In this traumatic situation [

14], residents had to harness their internal resources – initiative, self-efficacy, and a positive frame of mind [

27].

Steverink et al. [

31] pointed out that even when resources are declining, successful aging requires maintaining physical and social well-being. In the current study, participants who independently engaged in regular physical activity increased their self-management abilities, and this contributed to an improved emotional state after the outbreak of the pandemic. Interestingly, although initial (pre-training) self-management predicted four of the post-outbreak outcomes (anxiety, PTSD symptoms, life satisfaction, and general mood), it did not predict expectations for post-traumatic growth. However, the change in self-management following physical self-training over the two months from the outbreak of the pandemic did predict PTG, as well as the other outcomes. Thus, PTG behaved somewhat differently from the other outcomes.

Tedeschi and Calhoun [

50] suggested a functional-descriptive model of PTG, where it represents a positive psychological change that results from successfully dealing with the consequences of an event that might be traumatic for the individual (see also Tedeschi, Calhoun, & Cann, [

51]). The PTGI questionnaire [

46] aims to capture a subjective sense of coping well with traumatic events. However, the PTGI only measures subjects’ sense of change in PTG, not the internal factors that might underlie these processes. Therefore, PTG is an outcome and not a predictor. In the current study, it may be that PTG was predicted only by the change in self-management during the study period, and not by pre-training self-management, because it was specifically taking the initiative to engage independently in a program of exercise during those turbulent weeks – and thereby coping effectively with the trauma – that led the individual self-training group to experience a sense of psychological change and growth. That is, under conditions of lockdown, when escape was not possible, the self-training group realized that they had to take control over their own physical and mental well-being [

52]. Thus, the current results support the notion that growth is related to a subjective sense of effective coping.

4.1. Limitations

Several factors limit the generalizability of the current findings. First, our findings pertain to residents of a care home for the older adults, and not to older adults living in the community. Second, the psychological variables were measured only once, eight weeks after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Third, the current study looked only at the influence of physical training on self-management. The pandemic restrictions prevented us from studying other kinds of activities which are highly important in active aging, in particular social gatherings. Future research should examine broader populations over a longer span of time, and with reference to different aspects of active aging, especially now that effective vaccines against the SARS-CoV-2 virus have been developed and distributed. And finally, PTG behaved differently than the other psychological effects examined. While we suggested one possible explanation for this finding, future research should examine PTG in greater detail.

5. Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the present findings produce a relatively clear picture. Self-management abilities among older adults can be seen as a protective factor against the adverse psychological outcomes associated with traumatic events such as the Covid-19 pandemic. We found self-management to protect against anxiety, declines in life satisfaction, and the development of post-traumatic symptoms; and to contribute to expectations of post-traumatic growth. Furthermore, the improvement in self-management abilities through self-directed physical excises had a unique contribution beyond initial self-management abilities. Practitioners planning interventions among older adults should aim to enhance their self-management abilities and promote independent physical activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co.; methodology, I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co.; software, I.Z.; validation, D I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co; formal analysis, I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co; investigation, I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co; writing—original draft preparation, I.Z.; writing—review and editing, I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co; supervision, I.Z., D.Ca., and D.Co; project administration, I.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Authority of the College of Management – Academic Studies, Rishon Lezion, Israel, grant number 707015.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Management - Academic Studies, Rishon Lezion Israel (protocol 0126-2020, 24 January 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Forbes, M. K., & Krueger, R. F.The great recession and mental health in the United States. Clinical Psychological Science 2019, 7(5), 900-913. [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., ... & Eisner, M. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine 2022, 52(5), 824-833. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet 2020, 395 (10227), 912–920. [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L. Integrating cognitive and emotion paradigms to address the paradox of aging. Cognition and Emotion 2019, 33(1), 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Chen, Y., Lin, R., & Han, K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. Journal of Infection 2020, 80(6), e14–e18. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. T., Leung, K., Bushman, M., Kishore, N., Niehus, R., de Salazar, P. M., Cowling, B. J., Lipsitch, M., & Leung, G. M. Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nature Medicine 2020, 26(4), 506–510. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F., Zhao, S., Yu, B., Chen, Y. M., Wang, W., Song, Z. G., ... & Zhang, Y. Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269.

- Banerjee, D. Age and ageism in COVID-19: Elderly mental health-care vulnerabilities and needs. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102154. [CrossRef]

- Cahapay, M. Senior Citizens during COVID-19 Crisis in the Philippines: Enabling Laws, Current Issues, and Shared Efforts. Research on Ageing and Social Policy 2021, 9(1), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- İlgili, Ö., & Gökҫe Kutsal, Y. Impact of Covid-19 among the elderly population. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics 2020, 23(4), 419–423.

- Piacenza, F., & Ong, S. K. Impact of social distancing due to coronavirus disease 2019 in old age psychiatry. Psychogeriatrics 2021, 21(2), 258-259. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Y., & Tang, S. F. Perceived psychosocial health and its sociodemographic correlates in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: a community-based online study in China. Infectious diseases of poverty 2020, 9(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans, H., Steverink, N., Frieswijk, N., Buunk, B. P., Slaets, J. P., & Lindenberg, S. How to measure self-management abilities in older people by self-report. The development of the SMAS-30. Quality of Life Research 2005, 14(10), 2215–2228. [CrossRef]

- Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2020, 12(4), 331.

- Van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 2005, 18(5), 389-399. [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. R., Kallivayalil, D., Mendelsohn, M., & Harvey, M. R. Working the double edge: Unbraiding pathology and resiliency in the narratives of early-recovery trauma survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2012, 4(1), 102-111. [CrossRef]

- Fellman, D., Ritakallio, L., Waris, O., Jylkkä, J., & Laine, M. Beginning of the Pandemic: COVID-19-Elicited Anxiety as a Predictor of Working Memory Performance. Frontiers in psychology 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Helton, W. S., Head, J., & Kemp, S. Natural disaster induced cognitive disruption: Impacts on action slips. Consciousness and cognition 2011, 20(4), 1732-1737. [CrossRef]

- Dyregrov, A., Fjærestad, A., Gjestad, R., & Thimm, J. Young People's Risk Perception and Experience in Connection with COVID-19. Journal of Loss and Trauma 2020, 26(7), 597-610. [CrossRef]

- Özsungur, F. Successful aging management in social work. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Dergisi 2020, 15(1), 5277–5307.

- Havighurst, R. J. Successful aging. Processes of aging: Social and psychological perspectives 1963, 1, 299-320.

- Havighurst, R. J. A social-psychological perspective on aging. The Gerontologist 1968, 8(2), 67-71. [CrossRef]

- Corsi, M., & Samek, L. Active ageing and gender equality policies. EGGSI report for the European Commission, DG Employment, Social Affairs, and Equal Opportunities, Brussels 2011.

- Martínez de Miguel López, S., Escarbajal de Haro, A., & Salmerón Aroca, J. A. El educador social en los centros para personas mayores: respuestas socioeducativas para una nueva generación de mayores. Educar 2016, 52(2), 451-467.

- Cerri, C. Dependence and autonomy: an anthropological approach from the care of the elderly. Athenea Digital 2015, 15(2), 111–140. [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. Commentary: The emergence and application of active aging in Europe. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 2008, 21(1), 75–93. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, T., and Ponce de León, L. Social Work with Families 2011. Madrid: Academic Editions.

- Petersen, E., and Gasimova, L. Elderly people's existential loneliness experience throughout their life in Sweden and its correlation to emotional (subjective) well-being 2019. (Master's thesis, Halmstad University).

- Cramm, J. M., Hartgerink, J. M., Steyerberg, E. W., Bakker, T. J., Mackenbach, J. P., & Nieboer, A. P. Understanding older patients’ self-management abilities: functional loss, self-management, and well-being. Quality of Life Research 2013, 22(1), 85–92.

- Steverink, N., & Lindenberg, S. Do good self-managers have less physical and social resource deficits and more well-being in later life? European Journal of Ageing 2008, 5(3), 181–190.

- Steverink, N., Lindenberg, S., & Slaets, J. P. How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. European Journal of Ageing 2005, 2(4), 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Alma, M. A., Van der Mei, S. F., Feitsma, W. N., Groothoff, J. W., Van Tilburg, T. G., & Suurmeijer, T. P. Loneliness and self-management abilities in the visually impaired elderly. Journal of Aging and Health 2011, 23(5), 843–861. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., Bhoi, R., Ravan, J. R., Nath, S., Kar, N., & Padhy, S. K. COVID-19 pandemic and care of elderly: measures and challenges. Journal of Geriatric Care and Research 2020, 7(3), 143–146.

- Nieboer, A. P., Hajema, K., & Cramm, J. M. Relationships of self-management abilities to loneliness among older people: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics 2020, 20, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. The importance of health behaviours and especially broader self-management abilities for older Turkish immigrants. European Journal of Public Health 2018, 28(6), 1087–1092. [CrossRef]

- Vestjens, L., Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. A cross-sectional study investigating the relationships between self-management abilities, productive patient-professional interactions, and well-being of community-dwelling frail older people. European Journal of Ageing 2020, 18, 427–437. [CrossRef]

- Schoon, Y., Bongers, K. T., & Olde Rikkert, M. G. Feasibility study by a single-blind randomized controlled trial of self-management of mobility with a gait-speed feedback device by older persons at risk for falling. Assistive Technology 2020, 32(4), 222–228. [CrossRef]

- Rothan, H. A., & Byrareddy, S. N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Journal of Autoimmunity 2020, 109, 102433. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R., & Nellums, L. B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. The Lancet Public Health 2020, 5(5), e256.

- Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., Cornwell, E. Y., Koyanagi, A., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., ... & Koushede, V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health 2020, 5(1), e62–e70.

- de Miguel Lopez, S. M., Escarbajal de Haro, A., & Salmeron Aroca, J. A. Social educators at senior centers: A socio-educational response to a new generation of older people. Educar 2016, 52(2), 451–467. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D., Kosagisharaf, J. R., & Rao, T. S. ‘The dual pandemic’ of suicide and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatry Research 2020, 295, 113577. [CrossRef]

- Flores Tena, M. J. Prevent dependence on active aging during COVID-19. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine 2020, 7(7), 466-477.

- Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychological medicine 1983, 13(3), 595-605. [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) 2013. Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www. ptsd.va.gov.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1996, 9(3), 455-471.

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54(6), 1063-1070.

- Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., Patton, J. M., & Murray, K. A. The brief multidimensional students' life satisfaction scale-college version. American Journal of Health Behavior 2009, 33(5), 483-493.

- Cramm, J. M., Strating, M. M., de Vreede, P. L., Steverink, N., & Nieboer, A. P. Validation of the self-management ability scale (SMAS) and development and validation of a shorter scale (SMAS-S) among older patients shortly after hospitalisation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2012, 10(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. Post-traumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry 2004, 15, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G., & Cann, A. (2007). Evaluating resource gain: Understanding and misunderstanding posttraumatic growth. Applied Psychology: An International Review 2007, 56(3), 396–406. [CrossRef]

- Powell, S., Rosner, R., Butollo, W., Tedeschi, R.G., & Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth after war: A study with former refugees and displaced people in Sarajevo. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2003, 59, 71–83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).