1. Introduction

Digital technologies are become more and more an effective tool to document Cultural Heritage and sites, and to integrate new information and knowledge to digital models. In addition to capture shapes and metric data, digital survey techniques are going in the direction of adding different levels of knowledge to be connected to the 3D metric-morphological model [

1,

2]. This is a crucial added value in applying digitization as an extremely effective support for a huge set of analysis [

3], up to conservation and restoration purposes [

4], and current research directions towards the application of parametric modeling [

5,

6] and semantic enrichment of 3D models [

7,

8,

9] are additional expanding these applications.

This great potential can be also be addressed to tourism purposes [

10], supporting visitors’ deeper awareness on all possible dimensions of Cultural Heritage sites [

11]. While digital technologies are a widespread tool to document heritage buildings and sites, digital applications are indeed becoming more and more used to explore digital contents.

The increasingly widespread application of 3D digital survey technologies is leading to an ever growing number of digitized Cultural Heritage or landscape sites. However, this process needs further strengthening and a continue effort to digitize and digitally preserve Cultural Heritage assets, as indicated in the European Commission initiative called “European data space for Cultural Heritage” [

12]. The State of the Art is quite heterogeneous: often major or monumental sites have the opportunity to be digitized thanks to the availability of economic resources; “minor” sites or widespread heritage, when digitized thanks to research projects or local initiatives, struggle to reach broader audiences out of the specific initiative [

13]. This can be a shortcoming in supporting heritage institutions to find effective tools for the public to access, discover, explore and enjoy of cultural assets and to create innovative and creative services in the tourism sector.

Generally, there is a lack of digital applications to small or inappropriately so-called “minor” heritage sites, due to the reduced availability of economic resources, or the absence of appropriate sustainable strategies toward a pipeline able to make the best possible use of digital opportunities.

The recent pandemic crisis and the resulting drop in tourist flows - albeit temporary - has generated strong economic and social repercussions [

14] on geographical areas where tourism is the main source of economic activity and employment, and on small cultural institutions, deprived from their principal source of revenues which ensures their financial sustainability [

15]. Lately, large museums and the most popular heritage sites have gradually recovered from the crisis. However, minor sites and other cultural institutions which are excluded from the main tourist flows have a much lower degree of business resilience or financial sustainability. These small cultural sites, not included in the mass-tourism routes, play a key-role in social inclusion and territorial cohesion, and could be the key to open up to new strategies for sustainable tourism and heritage enhancement and fruition, also by local population.

Digital technologies such as 3D, cloud computing, Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR), are bringing extraordinary opportunities for digitization, online access and digital preservation, opening up new ways of digitally engaging with cultural content [

16]. When applied to Cultural Heritage, considering the uniqueness of heritage assets, these methodologies and applications need an integrated vision able to also address the needs of site managers, local cultural curators, citizens. New technologies are constantly evolving, and new digital media are increasingly used for accessing Cultural Heritage, but there is the need to find a different sensitivity and awareness in the approach to digital heritage for an active and sustainable accessibility.

Heritage fruition scenarios during and post pandemic condition put a great emphasis on the use of digital technologies for heritage sites accessibility [

17], giving new meanings to technologies for virtual tourism and remote fruition.

Under “ordinary” conditions, when the physical accessibility of heritage sites is not restricted, one of the focus points is the impact of mass tourism on renowned tourist destinations versus the lack of visitors of cultural sites off from the most popular routes. Before the pandemic crisis, urban studies already highlighted the need to solve the issue of mass tourism [

18]. After the pandemic, the need to smooth and diversify the tourist flows by moving them from the large attractors on different urban contexts is more and more evident [

19,

20], for social, economic and environmental reasons.

New economic strategies in tourism development and heritage enhancement and conservation are a urgent requirement especially for small, hidden, minor, unknown, inaccessible heritage sites [

21]. Without new forms of enhancement and accessibility, and economic resources, most of these sites are likely destined to disappear.

In this direction, there is a huge potential for innovation and experimentation using digital technologies and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration.

“Digital resources are handled sustainably if their utility for society is maximized, so that digital needs of contemporary and future generations are equally met. Digital needs are optimally met if resources are accessible to the largest number and reusable with minimal restrictions”: the [

22] statement, immediately highlights three major points: social utility of digital contents, accessibility, reuse of digital data.

There points are at the forefront of recent initiatives by the European Commission [

23,

24] aimed at finding new ways of ensuring better access to, understanding of and engagement with Cultural Heritage through digital technologies, with a particular focus on 3D models [

25].

From these studies, reports and initiatives, it is possible to evince that there is a need to find unconventional solutions exploiting digital opportunities, and there is a large room of improvement in terms of heritage digital contents’ creation, fruition and accessibility.

Moreover, the applications of digital technologies for survey and documentation are nowadays also addressed to the major issue of heritage at risk due to natural hazards, climate change effects [

26] and additional several threats, up to close or destruct sites, that could reborn to a second life in terms of preservation strategies, accessibility and tourism experiences thanks to technologies such as Virtual, Augmented or Mixed reality [

27]. This scenario indeed includes also inaccessible or abandoned heritage sites, many of which deserve to be put back into a circuit of knowledge, protection and identity awareness.

The challenge is to improve the design of cultural experiences by enhancing new understanding and resilient strategies for heritage documentation, preservation and fruition through digital means.

Many cultural sites too often fail to enter into virtuous systems of knowledge and exploitation, keeping hidden memories and stories of great identity value. There is a growing need to connect Cultural Heritage collections and sites revealing tangible and intangible heritage to citizens and tourists in their wider historical and geographical contexts.

Digital media have to be focused not only on visual and structural information, but also on stories and experiences connected to cultural and socio-historical context. The approach to digitization is liable to be fragmented, localized and static, the digitized cultural tangible (artefacts, historical sites) and intangible resources (stories, experiences, written memory of the society) are rarely interlinked, preventing deeper exploitation of the resources through wider searchability via different domains, networks or languages.

The paper aims to propose a methodological approach and conceptual model aimed at facing the following main challenges:

to open and diversify the tourist flows from the large attractors to culturally significant but little-known destinations, preventing over-tourism or reducing pressure in main renowned sites and giving new life to the minors;

to foster digitization and holistic documentation of heritage sites, at risk or marginalized;

to facilitate connections of minor sites into larger networks, proposing new approaches for handling visits in heritage sites and their surrounding area;

to relate tangible and intangible memories through digital;

to explore new economic opportunities in tourism development;

to contribute to solve the current fragmentation in heritage sites and collections digitization, finding new ways to put together different sources, reusing already digitized datasets;

to enrich personal fruition experiences, in the most possible inclusive way, fostering meaningful engagement of visitors and local people.

In order to create a workflow able to support the above mentioned action, the involvement of cultural institutions, regional and local authorities, stakeholders, citizens and creative industries, is essential in order to redistribute and balance tourist flows and related resources from major or renowned sites to sites suffering from a lack of visitors and attentions, making the most of the currently available digital technologies.

The development model proposed is based on the concept that sustainable heritage fruition and participation, economic strategies and digital technologies have to be integrated going together toward sustainable Cultural Heritage tourism [

28]. The proposal includes different dimensions of sustainability: cultural and social sustainability, sustainable economic growth, support of cultural diversity and traditions of local populations, according to the definition of sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities” [

29].

The main aim of the research is to outline a possible model or methodological schema for heritage fruition and enhancement, assuming digital technology as an enabler to reveal unknown assets in the most possible inclusive way.

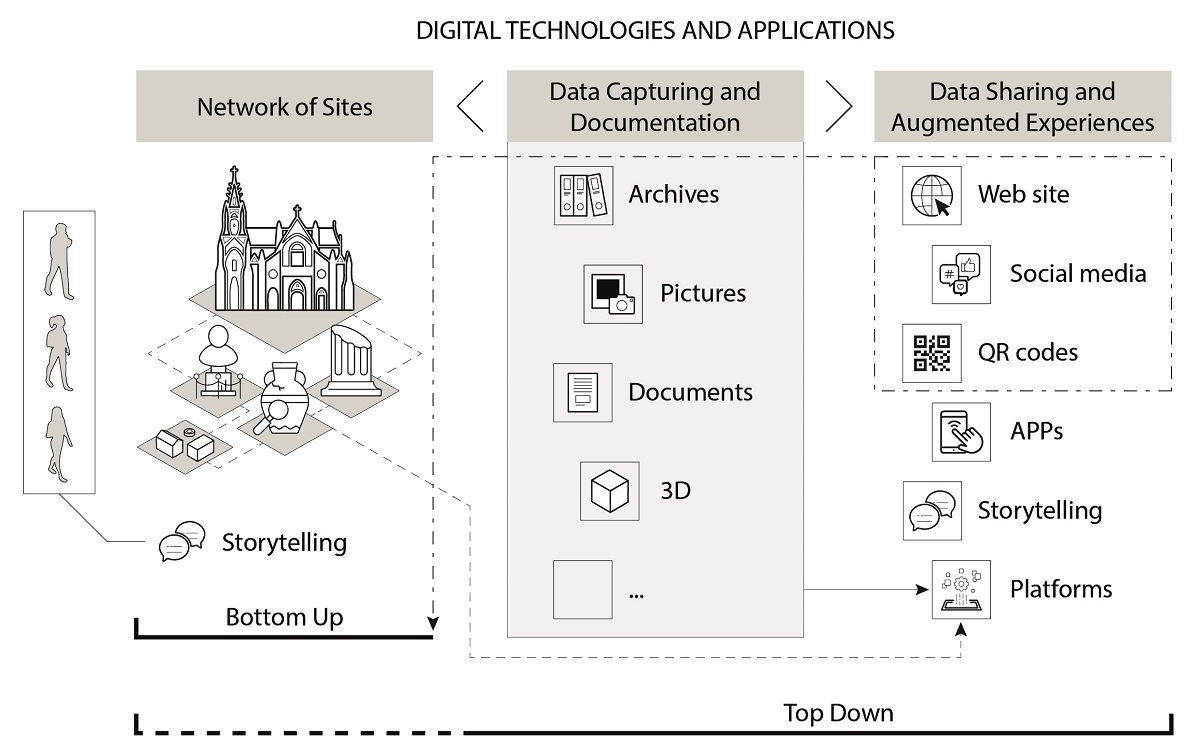

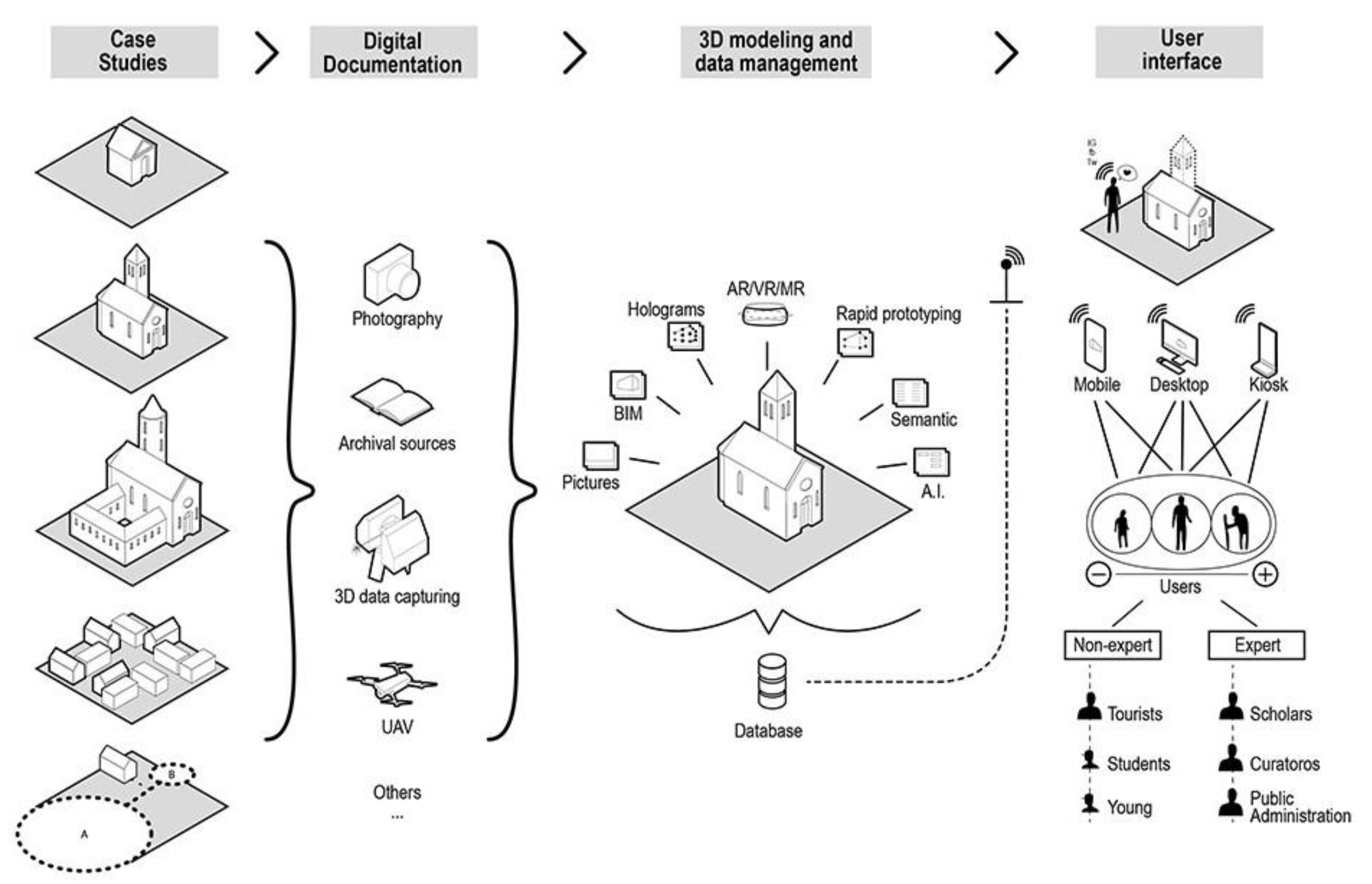

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the possible “universe of knowledge” to define an outline integrating small heritage sites or sites not included in conventional tourism routes, documentation and data input via different acquisition devices, data aggregation and outputs for the active fruition of cultural heritage and sites for the wide access of different users, experts and non-expert.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the possible “universe of knowledge” to define an outline integrating small heritage sites or sites not included in conventional tourism routes, documentation and data input via different acquisition devices, data aggregation and outputs for the active fruition of cultural heritage and sites for the wide access of different users, experts and non-expert.

In this direction, the focus is on “minor” or unknown heritage, seeking to solve the issue of unbalanced knowledge and cultural tourism between regions and sites, promoting unknown and unexplored heritage sites compared to high demand areas being overexploited in an unsustainable manner.

Heritage digitization, protection, and enhancement need to find new ways to exploit current opportunities offered by technological development according to a new sensitivity able to include new forms of exploration, understanding and imaginative experience.

2. Research scenarios and related works

The State of the Art in the field of digital technologies applied to Cultural Heritage tourism is wide and complex.

Scientific literature shows relevant studies at an interdisciplinary level, covering social sciences, sustainability issues, tourism analysis and statistics, urban studies, economics, and remote sensing applications related to heritage digitization or Cultural Heritage digital documentation in the broadest sense.

In recent years, studies on the topic have increased in number as a consequence of the Covid 19 pandemic [

30,

31]. In general terms, literature on sustainable tourism has exponentially grown in the last decades, being a central topic - linked to environmental, social and economic impacts – while connections between sustainable tourism and digital tools is currently at the forefront of the research in different scientific fields [

32].

However, studies on the application of technologies such as VR or AR in the field of tourism fruition and enhancement are well-established and have been presenting results for twenty years.

Studies on Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) developments related to tourism and sustainability goals highlight strengths and risks, and the need for more critical evaluations of the implications of the ICT economy [

33].

Digital applications cross the issue of tourism-related sustainability at different levels, from the dematerialization of several practices (booking, information material, maps) through the download of apps, almost always free of charge, contributing to reduce the environmental impact, to the deployment of immersive technologies.

The impact of VR and immersive applications in general can be considered as twofold. On the one hand, these tools enables remote access to cultural sites and contents, potentially increasing accessibility by different users categories, reducing inequalities and fostering inclusion in society (people with limited mobility, or affected by social isolation, or unable to physically travel) [

34]. On the other hand, the management of digital contents should be oriented towards encouraging physical access to heritage, and not vice versa [

35].

As a matter of fact, digital technologies have significantly changed the global ecosystem of the tourism industry (products, services, business ecosystems, destinations), starting from digital platforms with on-demand functionalities, creating new opportunities and challenges according to different markets, sub-sectors, and destinations, requiring new capacity-building, regulations and standards for digital services related to tourism. According to [

36], while many basic technologies associated with e-business have been included in operator services, higher levels of digitization are not as common.

For instance, storytelling through digital media is a powerful means for tourism and economic development, enabling strategic communication that supports sustainable competitive advantages [

37].

Digital technologies, web-based platforms and social media in the field of tourism can influence travel practices and tourists behavior [

38], while the use of immersive technologies, VR and AR applications on mobile devices has received increased attention in recent years [

39], generating new creative innovative opportunities for tourism, such as virtual simulations in order to digitally interact with destinations before plan the onsite visit [

40] or to enrich the on-site experience [

41,

42].

In recent years, immersive reality technologies such as AR, VR, Augmented Virtuality (AV), and Mixed Reality have become increasingly widespread for cultural knowledge dissemination, mainly for enriching personalized visiting experiences in Museums, but also applied to historical buildings and heritage sites [

43], or at historical city level [

44]. Recent studies foreshadow for the near future very promising developments in the fields of tourism, education, and entertainment, enriching 3D scenarios with different types of content [

45].

Projects and research aimed at documenting, storing and disseminating the Cultural Heritage starting from 3D data capturing or digitizing documents to create digital models for augmented applications for mobile devices such as tablets and smartphones produced very relevant and promising results also for future developments [

46,

47,

48]. Recent expansion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) connected to AR are bringing to rapid development and advancement of applications, software and devices to document, analyze and communicate space and artifacts, tangible and intangible Cultural Heritage [

49].

Despite research and development of applications that are achieving interesting advances in the field of digital documentation, data management and representation, in the tourism industry, conceptual grounding for which providers can leverage to create innovative immersive experiences is not fully mature [

50].

A possible direction to make the most from the current State of the Art is to go toward integrated systems able to combining the informative value of digital models (3D) with the intangible values that can be conveyed for tourism fruition at different levels. Starting from local administrations, cultural institutions or heritage site managers, a possible vision is to create new attractions or to add new dimensions to the visit experience, promoting the extension of the visit with “unconventional” routes to discover neighboring sites.

3. Materials and Methods

The conceptual framework here discussed is based on the analysis of the State of the Art and an overview of the current scenario, and it is based on experiences and considerations resulting from the author's participation in ongoing EU project in the field of Heritage digitization, such as “4CH - Competence Centre for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage” [

51] and “5Dculture - Deploying and Demonstrating a 3D Cultural Heritage space” aimed at enriching the offer of European 3D digital Cultural Heritage assets fostering their reuse in domains such as education, tourism and the wider cultural and creative sectors towards socially and economically sustainable outcomes.

The research idea is framed within the broad concept of digitization as a crucial means for protection, conservation, restoration, promotion, regeneration, dissemination, of Cultural Heritage.

The main concept is based on a possible approach - economically and environmentally sustainable - grounded on guidelines and indications set in a “model” to be provided to municipalities, local administrations or cultural institutes, or any local or territorial body or institution that needs to create new virtuous circuits in terms of sustainable tourist flows. Or for those sites that need an incentive to digitize contents that cannot be physically accessed (archival documentation, parts of the site not accessible to the public, intangible heritage) to enrich both the visit path and the remote use.

Starting from major or renowned heritage sites, the model is conceived to create connections and network routes. The main “node” should act as a driver to suggest additional visits in surrounding sites.

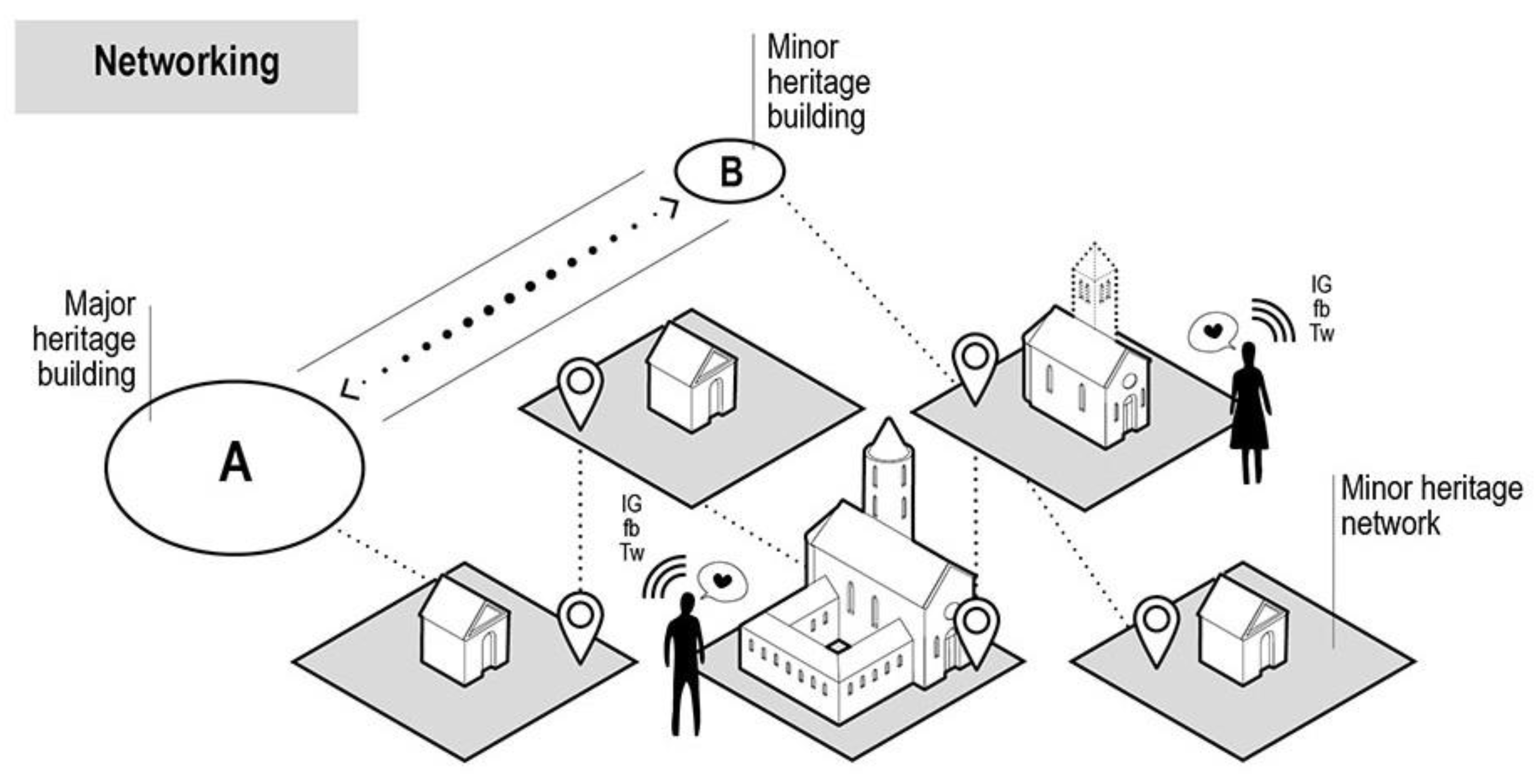

Figure 2.

Concept of sites’ networking. The renowned location can be the driver to create new and unconventional visits facilitating connections between minor sites into larger networks, proposing new approaches for handling visits in heritage sites and their surrounding area.

Figure 2.

Concept of sites’ networking. The renowned location can be the driver to create new and unconventional visits facilitating connections between minor sites into larger networks, proposing new approaches for handling visits in heritage sites and their surrounding area.

The concept is based on two levels: the one of digital documentation and the one of promotion and public engagement in a two way process. A scalable model depending on site features, needs and requirements, and on available resources (economic, human, technological), based on top-down and bottom-up actions that can be activated simultaneously or asynchronously considering different time spans according to different resources available, until converging.

The model can be conceived as a set of strategies and guidelines – as a first level – and a set of digital tools as a framework of indications as a more mature or structured level of action, most likely for the main site to be considered as the “promoter” of a network of other touristic destinations.

As a bottom-up strategy, several forms of storytelling can be activated, encouraging local population and tourists sharing their visits’ experiences via social media and platforms.

In this directions, storytelling [

52] is conceived as a way to communicate tourists impressions, stories and views through digital media, but also to enhance citizens or local population to share traditions, local customs, culture to enhance the visibility of the community [

53].

In order to put at the center the opportunities offered by digital technologies for heritage enhancement and fruition, the concept is structured considering all the possible digital media, starting from basic tools (a more effective use of cultural sites’ website information, the upload of digital contents in possible mobile applications, totem, QR codes), up to the creation of a 3D digital model of the heritage site, to be used for deeper digital experiences and as the basis for several applications for VR and AR. The heritage site manager or the cultural institution can create storytelling (from the supply side) through digital tools to create additional narratives.

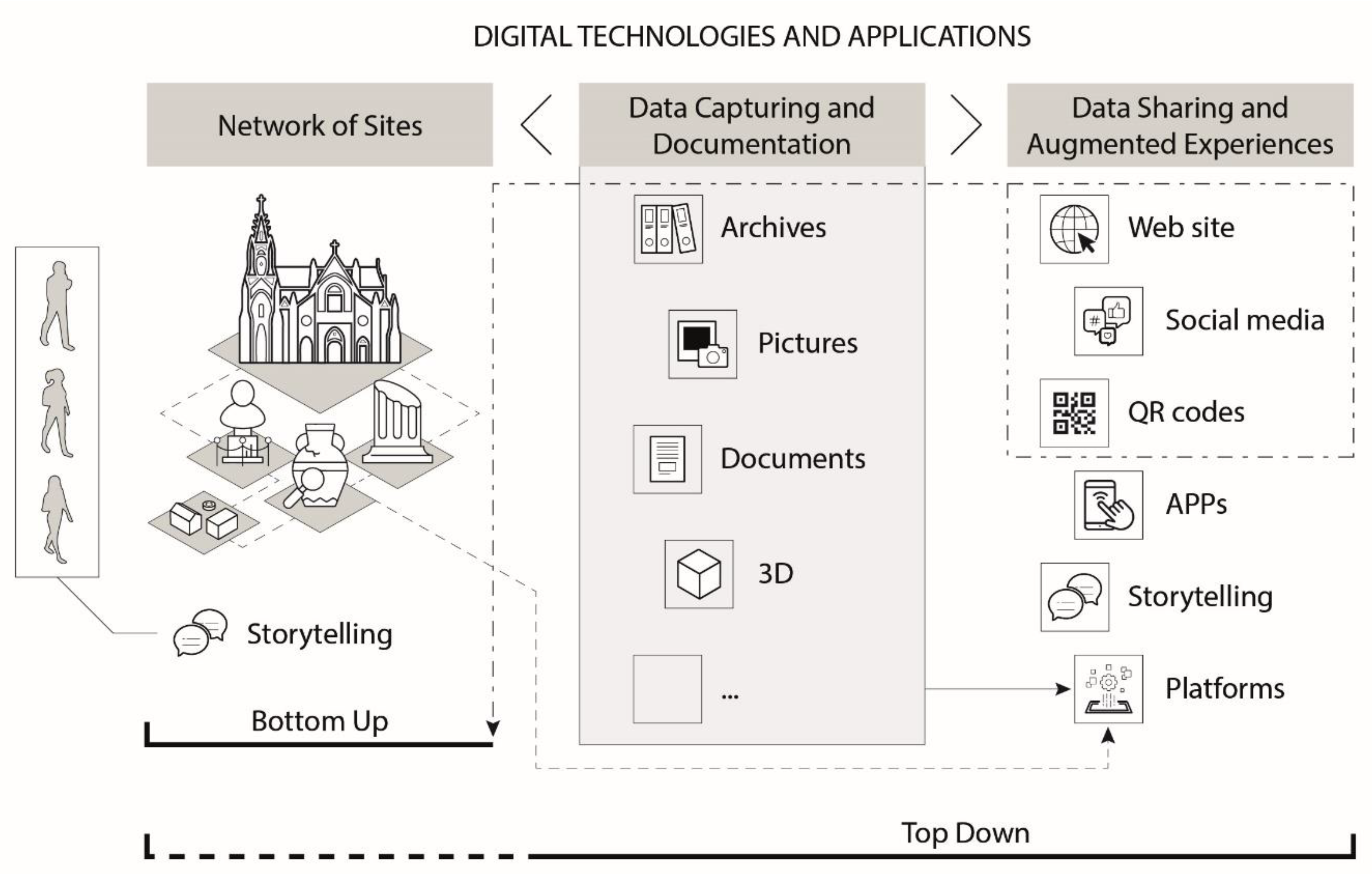

Figure 3.

Overall vision of the conceptual model, grounded on an efficient use of digital technologies, to be provided to heritage site managers, municipalities, local administrations or cultural institutes needing to increase sustainable tourist flows, set by integrating bottom-up and top-down actions and tools, fostering social participation.

Figure 3.

Overall vision of the conceptual model, grounded on an efficient use of digital technologies, to be provided to heritage site managers, municipalities, local administrations or cultural institutes needing to increase sustainable tourist flows, set by integrating bottom-up and top-down actions and tools, fostering social participation.

One of the main issues in this direction is economic; very often, small cultural sites hardly have the economic resources to set up digital survey, modelling and data management processes to produce digital models. The idea of creating a framework of bottom-up actions - and thanks to the network generated by the attractor site - is aimed at gradually increasing the income of the small or lesser known site, which can be reinvested in further actions for enhancement.

The model is conceived to be scalable and exportable, and organized as a kind of protocol of actions of different complexity. Priority or entry-level actions are related to the assessment phase, including:

identification of heritage site needs in terms of implementation of digital tools to improve forms of sustainable tourism and enhancement;

assessment of the potential network of neighboring sites or cultural destinations;

cataloguing and mapping of heritage buildings inaccessible not only to visitors but also unknown to local communities;

assessment of the level of development of available digital tools (website, social media connections, totem, apps, etc.);

assessment of digital resources available (digitized documents, 3D models, digitized iconographic sources, etc.);

assessment of potential financing funds or calls for tenders.

Depending on the different contexts, the relationship or agreements with governmental institutions and heritage management bodies will be crucial in determining the next steps of the top-down approach to channel resources for the upgrading of digital tools and skills.

Some additional considerations can be pointed out:

Despite the need for specialized personnel capable of producing digital models with high quality content, and the need for hardware and software infrastructure, 3D data capturing and digital documentations are possible today by exploiting low-cost technologies, such as Structure from Motion or Photomodelling starting from photographic survey;

The spread of open source software to manage digital data can help starting different kind of data processing to create digital contents to be shared;

The current direction at European level to accelerate digital transformation is creating unprecedented opportunities to use different fundings to boost digitization and capacities in the Cultural Heritage sector. Several initiatives and call for tenders or call for proposals are moving in this direction, creating relevant funding opportunities (programme such as Digital Europe, Horizon Europe, the Cohesion policy Funds, REACT-EU, the Technical Support Instrument and the Recovery Resilience Facility). Moreover, the already mentioned initiative for a “Common European data space for Cultural Heritage” is aimed not only at accelerating the digitization of all Cultural Heritage monuments and sites, but also to boost their reuse in domains such as education, sustainable tourism and cultural creative sectors. The Commission encourages Member States to digitize by 2030 all monuments and sites that are at risk of degradation and half of those highly frequented by tourists.

At national level, actions toward the enhancement of heritage fruition have been promoted by the European Commission, for instance the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan [

54] including a focus on tourism and culture, highlighting the need to improve culture and tourist accessibility through digital investments, promoting participation in culture, and the enhancement of sustainable tourism. Investments to achieve these goals include the “digital strategy” and platforms for Cultural Heritage and regeneration of small cultural sites, to foster the development of new tourism/cultural experiences and balance tourist flows in a sustainable way [

55]. Under this umbrella, the Digital Library of the Italian Ministry of Culture has the mission to accompany cultural institutions and sites in implementing their digital transformation, to redesign the way they interact with Cultural Heritage, to develop new models in an ecosystem approach.

A very relevant point, is indeed the reuse of digital contents already available. The widespread heritage 3D digital documentation is a process started a long time ago – and currently even faster and spread – producing several databases and 3D models that could be shared, explored, reused. There are several major sites (potential attractors to promote surrounding visits) and small sites, already digitized, that could be collected and enriched.

A two-ways strategy for heritage contents storytelling can be activated, bottom-up and top-down, the latter conceived as an advanced exploitation of digital contents by the cultural institution or the site manager. The bottom-up strategy can trigger possible participatory to make people create and interact with digital contents.

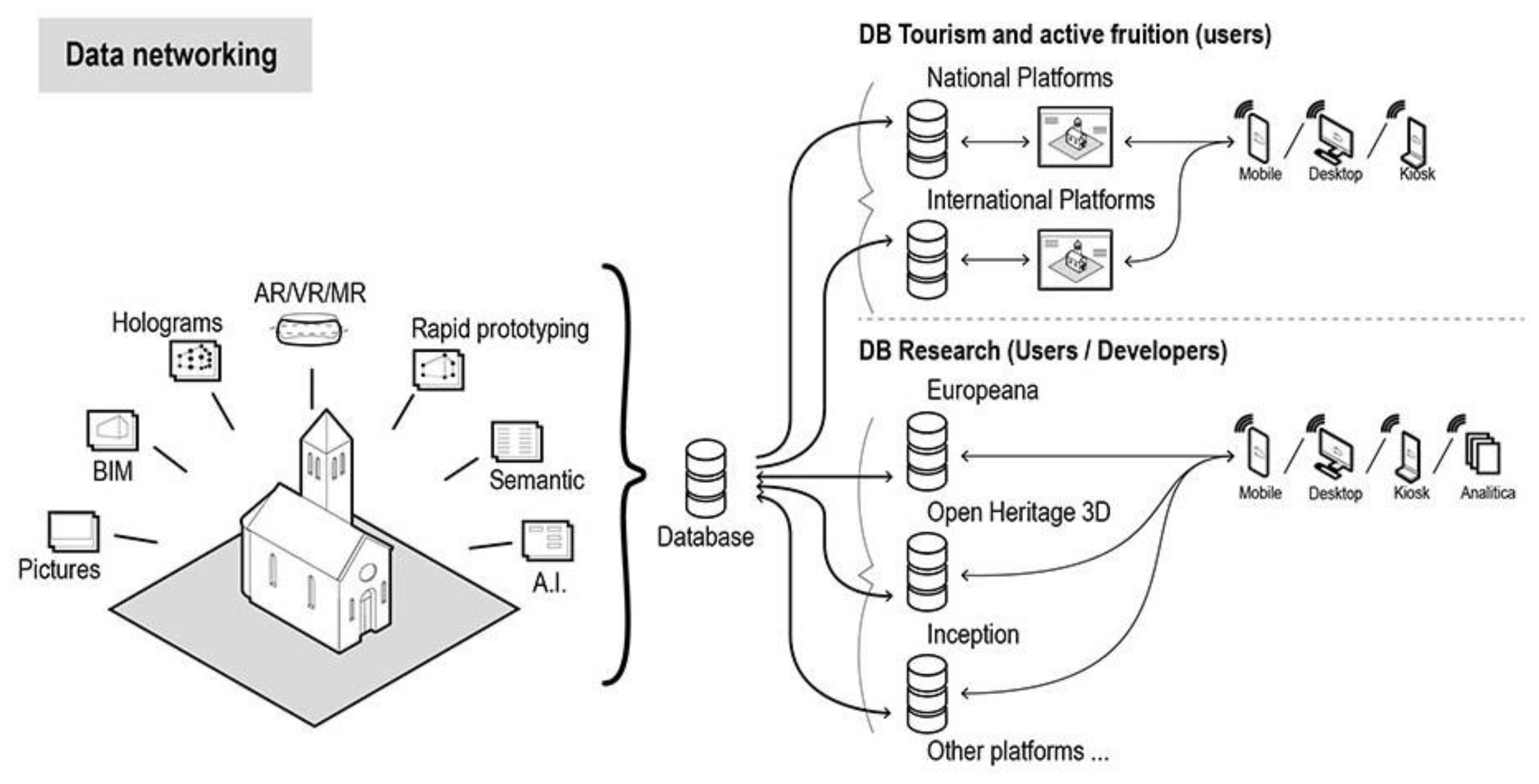

The topic of aggregator platforms to collect and make heritage digital contents available and accessible is topical as well. The Data space initiative will draw the direction, but in the meanwhile several platforms and digital infrastructures are available to share 2D and 3D heritage contents to collect and share digital models.

Figure 4.

Possible fallout in terms of sharing data and document sources through existing platforms to disseminate digital contents. Europeana, Open Heritage and Open Heritage Labs, Open Heritage 3D, Inception, are some examples of digital data collector and aggregator on which ground additional applications.

Figure 4.

Possible fallout in terms of sharing data and document sources through existing platforms to disseminate digital contents. Europeana, Open Heritage and Open Heritage Labs, Open Heritage 3D, Inception, are some examples of digital data collector and aggregator on which ground additional applications.

This outline is aimed at defining a framework for possible approaches to the inclusion and fruition of minor, hidden or inaccessible heritage, or spaces at the limits of the conventional tourist routes, to be recovered and reconnected. The way latest technologies are applied to digitally document tangible and intangible heritage needs to be oriented including different dimensional scales (sites, buildings, artworks, etc.) by enhancing engaging narrations, story-telling, and linking physically separated objects and sites.

Catalysts are needed for the renewal of the cultural identities of otherwise neglected places that, if enhanced, can renovate interest in the populations and foster social and economic positive impacts.

4. Possible impacts

The overall workflow outlined in the present paper can be a strategy proposal to foster procedures of sustainable touristic development through digital tools.

Although current efforts in terms of digitization are geared towards sites with higher tourist numbers and towards heritage at risk [

56], the proposed strategy focuses on minor and diffuse heritage as a possible driver for new approaches to sustainable tourism.

This historic moment foreshadows great accelerations in terms of development and technological applications, especially related to the digital domain, but the issues at the level of local management of small sites or those outside the major economic circuits is vital. The gap between small heritage assets to be safeguarded and technological advancement is not so unbridgeable, but a comprehensive strategy is needed.

The proposal can foster interdisciplinary collaborations, including social science and public engagement, to activate pilot experimentations of bottom-up and top-down strategies toward the increasing adoption of digital tools, considering the high potential of making accessible, interlinking, disseminating and preserving sites and collections. Nevertheless, there is a need to set up a systematization of documentation procedures and a careful and critical selection and verification of information to be included in the additional layers of knowledge that digital systems allow. While in this sense there are several best practices and guidelines [

57,

58], copyright-related issues when digitizing and sharing Cultural Heritage are still a shortcoming to be faced.

From a social point of view, the rediscover and promotion by digital media of sites only marginally known but expressive of a cultural reality worthy of attention, can arise a social awareness and sense of belonging by local communities. The outlined conceptual framework is indeed focused at giving access to cultural contents and resources to as many people as possible, by using functionalities and applications (web sites, databases, digital libraries, virtual applications, etc.), overcoming cultural, environmental, and management barriers, while promoting easier and widespread fruitions.

From an economic point of view, cultural tourism represents up to 40% of all tourism in Europe [

59], and Cultural Heritage is an essential part of cultural tourism. Digitization of Cultural Heritage assets and the reuse of such content can generate new jobs, be a driver for cultural initiatives and a channel to find new economic resources bringing in new tourist flows. As far as current funding opportunities are concerned, the point is to draw up procedures for accessing funding that are sufficiently simplified to be managed even by small institutions.

The setting up of the conceptual framework can flow into good practices, both at a managerial and technological level, proposing innovative communication strategies allowing reaching a cultural appropriation through easy-to-understand systems.

Stakeholders and target groups to whom this framework is geared are manifold. Professionals, scholars, and researchers can be involved toward the effective application of documentation through digital resources for analysis, conservation actions, knowledge enhancement. Local communities, citizens and tourists can benefit from new form of access, fostering the rediscover of local heritage, and encouraging new visit routs. Curators, asset managers, public administrations can find new forms of enhancement, exploitation and business models. Online access [

60] to documented digital replicas (including storytelling) of artefacts, augmented visits to sites and monuments and new accesses to archive documents may increase the appeal and promotion of a place, a building, a site, a museum, a city, moving new tourism and increasing local economy. Young people and students can be involved for training and education activities [

61,

62], as well as for participation actions. The participatory, educational and training fallout is central within the concept of sustainable tourism and it is aimed both at local communities and citizens (through storytelling tools), and at curators, experts, professional and stakeholders involved in heritage preservation (through applications for advanced uses of digital models for conservation actions).

Digital technologies can be the catalysts for the renewal of the cultural identity of a place and the strengthening of social involvement through new approaches for handling visits in heritage sites and their surrounding areas according to the concept of Network of sites, finding unconventional paths of knowledge in which the real and the virtual are able to dialogue.

5. Discussion

The workflow proposal is based on the setting up a “model” – flexible and scalable – grounded on an efficient use of digital technologies, to be provided to heritage site managers, municipalities, local administrations or cultural institutes that needs to create new approaches to knowledge and to the increasing of sustainable tourist flows, focusing on small or minor sites out from conventional routes.

The development of a set of integrated bottom-up and top-down actions and tools can enable the exploitation of virtual applications, experimenting digital opportunities on real contexts, merging missing memories with tangible legacy and fostering social participation.

Digital technologies allow to add several level of knowledge to a site, including intangible values, “traces” and remains, not only physical but also documentary and immaterial assets, contained in physical places that narrate heritage spaces and sites. Single “objects” can be potentially organized in rout networks, where tangible and intangible memories can be related, in order to enhance hidden but valuable places.

The brief discussion here proposed, theoretically embedded, does not resolve the entire structure of an approach that presents different levels of complexity and different variable parameters, depending on the specific context. Anyway, a comprehensive view of the current scenario and the focus on the potential of digital applications for “minor” assets can be the starting point for the definition of possible strategies to outline a cross-approach pipeline for small, unknown or not enhanced heritage sites.

The proposed methodological approach can be considered as a first step in further developing a “model” that could help small cultural institutions to find their way to manage all the opportunities that digital technologies offer, toward cultural and social sustainability.

While the issue of “quality” of digital data produced [

63] should be discussed deeply, the quantity of digital contents is growing exponentially; this large amount of data presents an increasing challenge of management to curators and public administrations toward an adaptation of the current fruition of heritage toward a sustainable and inclusive access [

64].

An additional crucial point is to strengthen the concept and meanings of accessibility, through the creation of networks, creating connections among places and individuals, shifting attention to the great added value that digital technology can bring in merging the social dimension of inclusiveness and active fruition into a process usually fragmented and expert-oriented, increasing heritage awareness by addressing knowledge methodologies and governance rather than mere technological tools; bringing methodological innovation, mapping relationships and practices, rather than technologies.

Another major challenge is related to the digital skills gap [

65] in the sector: Cultural Heritage institutions need to be able to exploit the opportunities offered by advanced digital technologies, and to be aware about possible tools to be easily exploited. For instance, several existing platforms can be an entry level to disseminate digital contents (Europeana; Open Heritage and Open Heritage Labs; Open Heritage 3D, Inception, etc.), while other specific platform to upload digital models and applications should be carefully analyzed, setting specific tools for web navigation and virtual tours, reconstructions, immersive features and so on. The potential applicability of tailored digital contents in local digital networks and international platforms [

66] is high and offer different opportunities.

Additional chances to access different kind of services as a support in fostering digitization capabilities are related to the connection with ongoing project; for example, the already mentioned 4CH project is working in the direction of setting up the methodological, procedural, and organizational framework of a Competence Centre able to work with a network of national, regional, and local Cultural Institutions, providing them with advice, support, and services focused on the preservation and conservation of historical monuments and sites, giving access to training services, repositories of data, metadata, standards and guidelines.

6. Conclusion

Cultural Heritage is a shared resource, to raise awareness and reinforce a sense of common identity, and a transformative force for communities regeneration, strengthening links between culture and education, social aspects, urban policies, research and innovation, as stated in “A New European Agenda for Culture” by the European Commission [

67].

A central point concerns the opportunity to bring citizens closer to the cultural institutions of their territory through a more open and inclusive governance model, promoting a real opening of the institutions that incorporate the use of information and communication technologies [

68,

69] in terms of transparency and dialogue with the citizens.

Human-technology interaction is becoming increasingly disruptive (not only among young people, who needs to find alternative uses of digital devices), and this is producing several cross-cutting social impacts.

Interacting with digital heritage contents in a meaningful and effective way is a goal to be reached, considering that, even if we are living in a digital world, tourism and cultural routes are still grounded mainly on traditional practices.

Nevertheless, touristic development models to approach sustainability in a new and broad way are needed, as well as technologies addressed to tourists for helping them understanding Cultural Heritage sites in all possible dimensions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Centofanti, M.; Brusaporci, S.; Lucchese, V. Architectural Heritage and 3D Models. Computational Modeling of Objects Presented in Images; Di Giamberardino, P., Iacoviello, D., Natal Jorge, R., Tavares, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Barsanti, S. G.; Remondino, F.; Fenández-Palacios, B. J.; Visintini, D. Critical Factors and Guidelines for 3D Surveying and Modelling in Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2014, 3(1), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; De Luca, L. Semantic-driven analysis and classification in architectural heritage. Disegnarecon 2021, 14(26), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Grilli, E.; Remondino, F. Classification of 3D digital heritage. Remote Sens 2019, 11(7), 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Lerones, P.; Olmedo, D.; López-Vidal, A.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Zalama, E. BIM Supported Surveying and Imaging Combination for Heritage Conservation. Remote Sens. 2021, 13(84), 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, G.; Bertolini, F.; Bevilacqua, M. G.; Caroti, G.; Martínez-Espejo Zaragoza, I.; Martino, M.; Piemonte, A. HBIM Methodologies for the Architectural Restoration. The Case of the Ex-Church of San Quirico All'Olivo in Lucca, Tuscany. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W11, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L. Methods, formalisms and tools for the semantic-based surveying and representation of architectural heritage. Appl Geomat 2014, 6, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, V.; Caroti, G.; De Luca, L.; Jacquot, K.; Piemonte, A.; Véron, P. From the semantic point cloud to heritage-building information modeling: a semiautomatic approach exploiting machine learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13(3), 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruggi, S.; Grilli, E.; Russo, M.; Fassi, F.; Remondino, F. A hierarchical machine learning approach for multi-level and multi-resolution 3D point cloud classification. Remote Sens 2020, 12(16), 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdicca, R.; Paolanti, M.; Frontoni, E. eTourism: ICT and its role for tourism management. J. Hosp. Tour 2019, 10(1), 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Pavía, S.; Cahill, J.; Lenihan, S.; Corns, A. An initial design framework for virtual historic Dublin. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission proposes a common European data space for cultural heritage; 2021. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-proposes-common-european-data-space-cultural-heritage (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Salerno, R. Digital technologies for “minor” cultural landscapes knowledge: Sharing values in heritage and tourism perspective. In Geospatial intelligence: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications; IGI Global: Hershey, Pennsylvania, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 1645–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Covid-19 & beyond. Challenges and opportunities for cultural heritage; 2020. Available online: https://www.europanostra.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/20201014_COVID19_Consultation-Paper_EN.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- IDEA Consult, Goethe-Institut, Amann, S., & Heinsius, J. Research for CULT committee—Cultural and creative sectors in post-Covid-19 Europe: Crisis effects and policy recommendations. European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies; 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2021)652242 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Bekele, M. K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni E., S.; Gain, J. A survey of augmented, virtual, and mixed reality for cultural heritage. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Heritage 2018, 11(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, T. (Ed.); Adetunji, O.; Jurčys, P.; Niar, S.; Okahashi, J.; Rush, V. The impact of COVID-19 on heritage: An overview of responses by ICOMOS National Committees and Paths Forward. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2415/ (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is ‘overtourism’a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23(18), 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andria, E.; Fiore, P.; Nesticò, A. Strategies for the Valorisation of Small Towns in Inland Areas: Critical Analysis. In New Metropolitan Perspectives. Post COVID Dynamics: Green and Digital Transition, between Metropolitan and Return to Villages Perspectives; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022, vol 482, pp 1790–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Naramski, M.; Szromek, A. R.; Herman, K.; Polok, G. Assessment of the activities of European cultural heritage tourism sites during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov.: Technol. Mark. Complex 2022, 8(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizio, I.; Brusaporci, S.; Luigini, A.; Ruggieri, A.; Basso, A.; Maiezza, P.; Tata, A.; Giannangeli, A. Experiencing the inaccessible. A framework for virtual interpretation and visualization of remote, risky or restricted access heritage places. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W15, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapp, M.; Open Government Data and Free Software - Cornerstones of a Digital Sustainability Agenda. In The 2013 Open Reader—Stories and Articles Inspired by OKCon 2013: Open Data, Broad, Deep, Connected; 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marcus_Dapp/publication/309792312_Open_Government_Data_and_Free_Software_-_Cornerstones_of_a_Digital_Sustainability_Agenda/links/5823aee808ae61258e3cbf4d.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Commission recommendation on a common European data space for cultural heritage; 2021. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-proposes-common-european-data-space-culturalheritage (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Basic principles and tips for 3D digitisation of cultural heritage; 2020. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/basic-principles-and-tips-3d-digitisation-cultural-heritage (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- 3D content in Europeana task force; 2020. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/project/3d-content-in-europeana (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Markham, A.; Osipova, E.; Lafrenz Samuels, K.; Caldas, A.; World heritage and tourism in a changing climate. United Nations Environment Programme/United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2016. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/139944 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Schaffer, V.; Timms, K. Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tour. Manage. 2021, 83, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Shirvani Dastgerdi, A.; Francini, C.; Liberatore, G. Sustainable cultural heritage planning and management of overtourism in art cities: Lessons from atlas world heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12(9), 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council; 2020. Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Palazzo, M.; Gigauri, I.; Panait, M. C.; Apostu, S. A.; Siano, A. Sustainable Tourism Issues in European Countries during the Global Pandemic Crisis. Sustainability 2022, 14(7), 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasoli, M. Small Historical Centres: an opportunity for the “smart” revitalization of Inner Areas in the Post (post) COVID Era. Technical Transactions 2021, 118(1).

- Della Corte, V.; Del Gaudio, G.; Sepe, F.; Sciarelli, F. Sustainable Tourism in the Open Innovation Realm: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Tourism, technology and ICT: a critical review of affordances and concessions. J. Sustainable Tour. 2021, 29(5), 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nuenen, T.; Scarles, C. Advancements in technology and digital media in tourism. Tourist Stud. 2021, 21(1), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, N.; Mahroof Khan, M.; Ashraf, S.; Hashmi, M. S.; Khan, M. M.; Hishan, S. S. Post-COVID 19 tourism: will digital tourism replace mass tourism? Sustainability 2021, 13(10), 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Phi, G. T. L.; Mahadevan, R.; Meehan, E.; Popescu, E.; Digitalisation in Tourism: In-depth analysis of challenges and opportunities. Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (EASME), European Commission; 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/33163/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Bassano, C.; Barile, S.; Piciocchi, P.; Spohrer, J.C.; Iandolo, F.; Fisk, R. Storytelling about places: Tourism marketing in the digital age. Cities 2019, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nuenen, T.; Scarles, C. Advancements in technology and digital media in tourism. Tourist Stud. 2021, 21(1), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; tom Dieck, M. C.; Moorhouse, N.; tom Dieck, D. Tourists' experience of Virtual Reality applications. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2017; pp. 208–210.

- Yung, R.; C. Khoo-Lattimore. New Realities: A Systematic Literature Review on Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality in Tourism Research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22(17), 2056–2081.

- Corrigan-kavanagh, E. ; C. Scarles ; G. Revill. Augmenting Travel Guides for Enriching Travel Experiences. eRTR e-Review of Tourism Research 2019, 17(3), 334–348.

- tom Dieck, M. C.; T. H. Jung. Value of Augmented Reality at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Stakeholder Approach. J. Dest. Mark. Manage. 2017, 6(2), 110–117.

- Bekele, M.K,; Champion, E. A Comparison of Immersive Realities and Interaction Methods: Cultural Learning in Virtual Heritage. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6:91.

- Brusaporci, S.; Graziosi, F.; Franchi, F.; Maiezza, P.; Tata, A. Mixed Reality Experiences for the Historical Storytelling of Cultural Heritage. In From Building Information Modelling to Mixed Reality; Bolognesi, C., Villa, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fanini, B.; Pagano, A.; Pietroni, E.; Ferdani, D.; Demetrescu, E.; Palombini, A. Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage. In Springer Handbook of Augmented Reality; Nee, A.Y.C., Ong, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, V.; Spallone, R.; Vitali, M. Augmented Turin Baroque Atria: AR Experiences for Enhancing Cultural Heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W9, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spallone, R.; Lamberti, F.; Guglielminotti Trivel, M.; Ronco, F.; Tamantini, S. 3D Reconstruction and Presentation of Cultural Heritage: AR and VR Experiences at the Museo D’Arte Orientale di Torino. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2021, XLVI-M-1-2021, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigini, A.; Brusaporci, S.; Basso, A.; Vattano, S.; Maiezza, P.; Trizio, I.; Tata, A. Digital experience for the enhancement of cultural heritage. VR and AR models of the Valentin im Viertel farmhouse. In 3D Modeling & BIM–Modelli e soluzioni per la digitalizzazione; Empler, T., Fusinetti, A. Eds; DEI; Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 440–466.

- Giordano, A.; Russo, M.; Spallone, R. Representation Challenges: Augmented Reality and Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage and Innovative Design Domain; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Timms, K.; Schaffer, V.; Skavronskaya, L.; Little, C. Management of immersive heritage tourism experiences: A conceptual model. Tour. Manage. 2019, 72, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaia, E.; Maietti, F.; Di Giulio, R.; Iadanza, E. ICT and Digital Technologies. The New European Competence Centre for the Preservation and Conservation of Cultural Heritage. In Trandisciplinary Multispectral Modelling and Cooperation for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Moropoulou, A., Georgopoulos, A., Doulamis, A., Ioannides, M., Ronchi, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ippoliti, E.; Casale, A. Representations of the City. The Diffuse Museum The Esquilino Tales. diségno 2021, 8, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Roque, M. I. Storytelling in Cultural Heritage: Tourism and Community Engagement. In Global Perspectives on Strategic Storytelling in Destination Marketing. IGI Global: Hershey, Pennsylvania, 2022; pp. 22–37.

- Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza; 2021. Available online: https://www.governo.it/it/articolo/piano-nazionale-di-ripresa-e-resilienza/16782 and https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Maietti, F. Digital Documentation for Enhancement and Conservation of Minor or Inaccessible Heritage Sites. In Cultural Leadership in Transition Tourism. Contributions to Management Science; Borin, E., Cerquetti, M., Crispí, M., Urbano, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, I.; Drdácký, M.; Vintzileou, E.; Bonazza, A.; Hanus, C.; Safeguarding cultural heritage from natural and man-made disasters. A comparative analysis of risk management in the EU. European Commission Publication Office; 2021. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/224310 (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Europe’s Digital Decade: digital targets for 2030; 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/europes-digital-decade-digital-targets-2030_en (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Study on quality in 3D digitisation of tangible cultural heritage; 2022. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/study-quality-3d-digitisation-tangible-cultural-heritage (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Tourism and Culture Synergies, World Tourism Organization UNWTO; 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284418978 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- European Commission Recommendation of 27 October 2011 on the Digitisation and Online Accessibility of Cultural Material and Digital Preservation (2011/711/EU); 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:283:0039:0045:EN:PDF (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Bolognesi, C.; Aiello, D. Learning through serious games: a digital museum for education. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIII-B5-2020, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigini, A., Panciroli, C. Ambienti digitali per l’educazione all’arte e al patrimonio. FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2018. 2018.

- Denard, H. London Charter for computer-based visualization of Cultural Heritage; 2009. Available online: www.londoncharter.org (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Dhonju, H.K.; Xiao, W.; Mills, J.P.; Sarhosis, V. Share Our Cultural Heritage (SOCH): Worldwide 3D Heritage Reconstruction and Visualization via Web and Mobile GIS. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Recovery and Resilience Facility. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/economic-recovery/recovery-and-resilience-facility_en (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Myers, D. ; Quintero. M.S. ; Dalgity, A. ; Avramides, I. The Arches heritage inventory and management system: a platform for the heritage field. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6(2), 213–224.

- A New European Agenda for Culture; 2020. Available online: https://culture.ec.europa.eu/document/a-new-european-agenda-for-culture-swd2018-267-final (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Ippoliti, E.; Meschini, A. Tecnologie per la comunicazione del patrimonio culturale. Disegnarecon 2011, 4(8).

- The ICOMOS Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites; 2008. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/interpretation_e.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).