Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Description

2.1. Experimental Materials Used

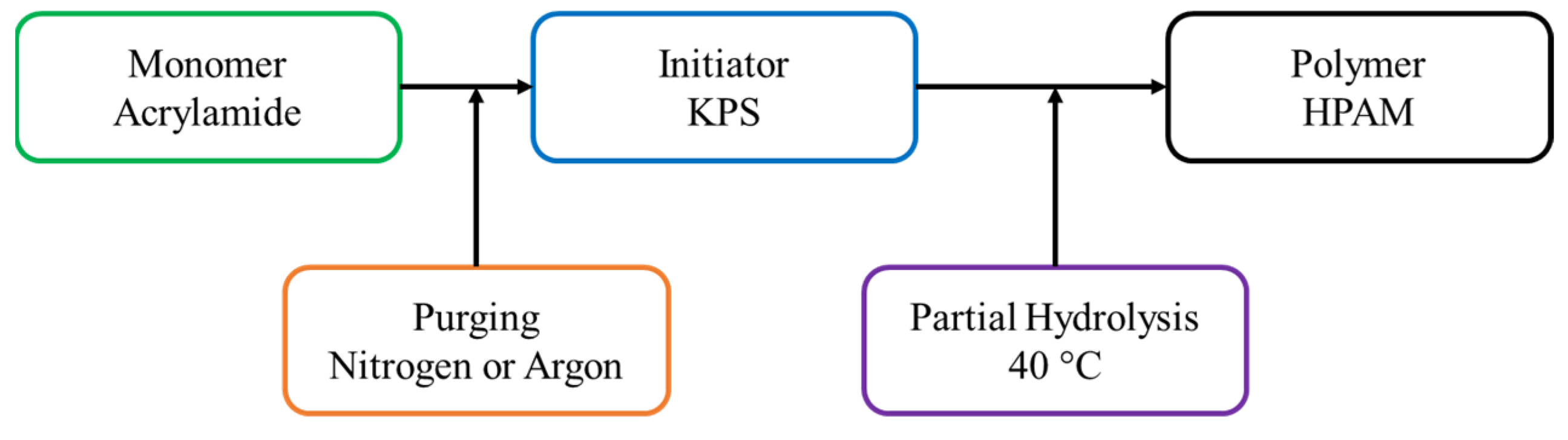

2.2. Polymer Synthesis

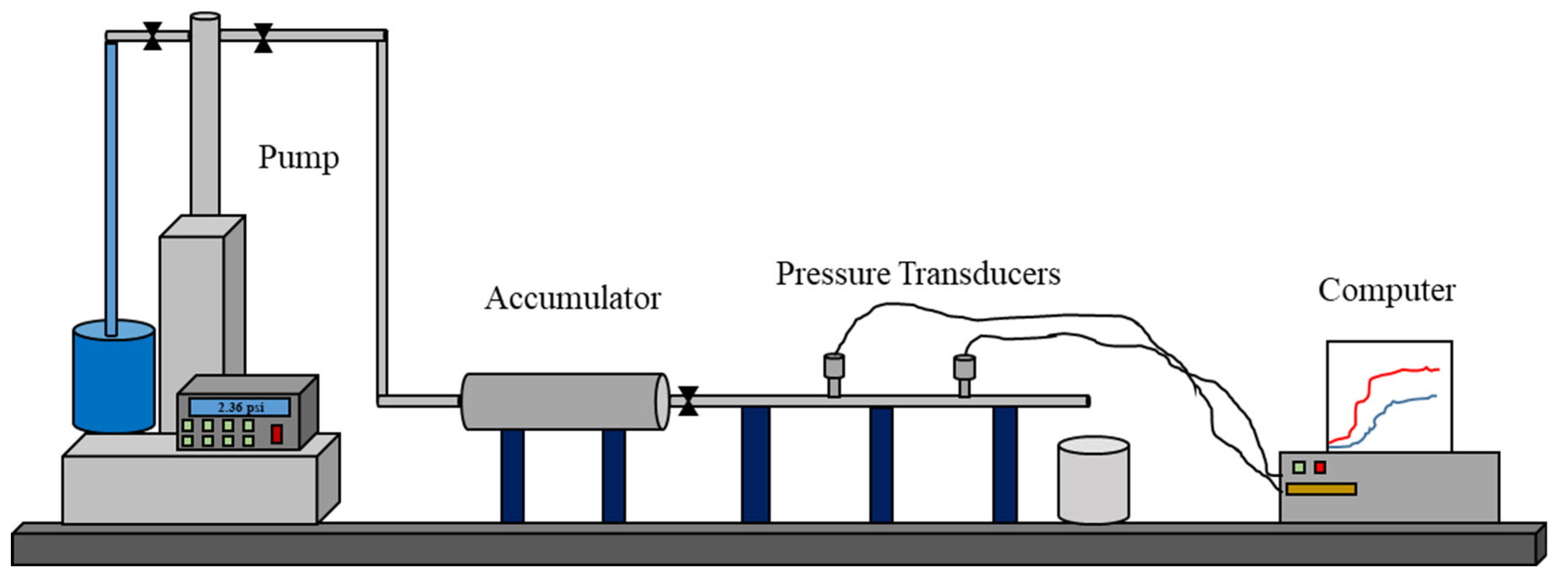

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. Experimental Procedure

- -

- Synthesis the polymer using the polymer synthesis procedure discussed above and then hydrolyze the polymer by placing it in the oven until it reaches 10-15% hydrolysis. Dehydrate the polymer until it becomes a dry white powder.

- -

- Prepare the polymer solution by placing the polymer powder in the distilled water and stirring the mixture for at least 12 hours using a magnetic stirrer. The solution should be covered during stirring to avoid any contaminants from entering the solution during the mixing process.

- -

- Place the polymer in the accumulator and ensure that there are no air pockets between the polymer which may impact the experiments. Also, the accumulator must be fully occupied by the polymer.

- -

- Connect the tube to the accumulator and attach the pressure transducers after they have been calibrated.

- -

- Begin the polymer injection using the lowest flowrate. Each flowrate is stopped when the pressure becomes stable for at least two pore volumes of injection.

- -

- Once the experiment is concluded, the accumulator and tube are cleaned and prepared for the following experiments.

3. Results and Discussion

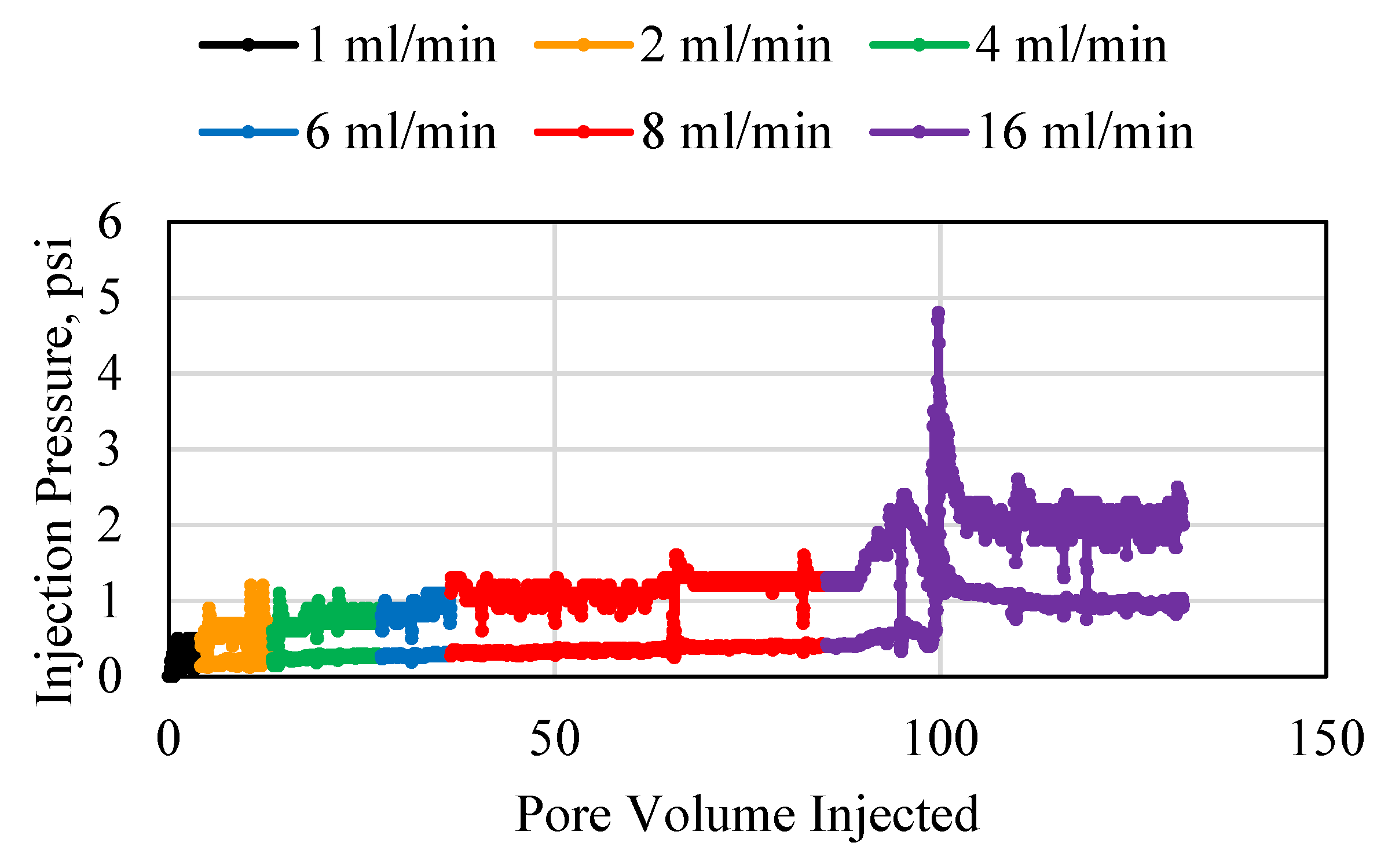

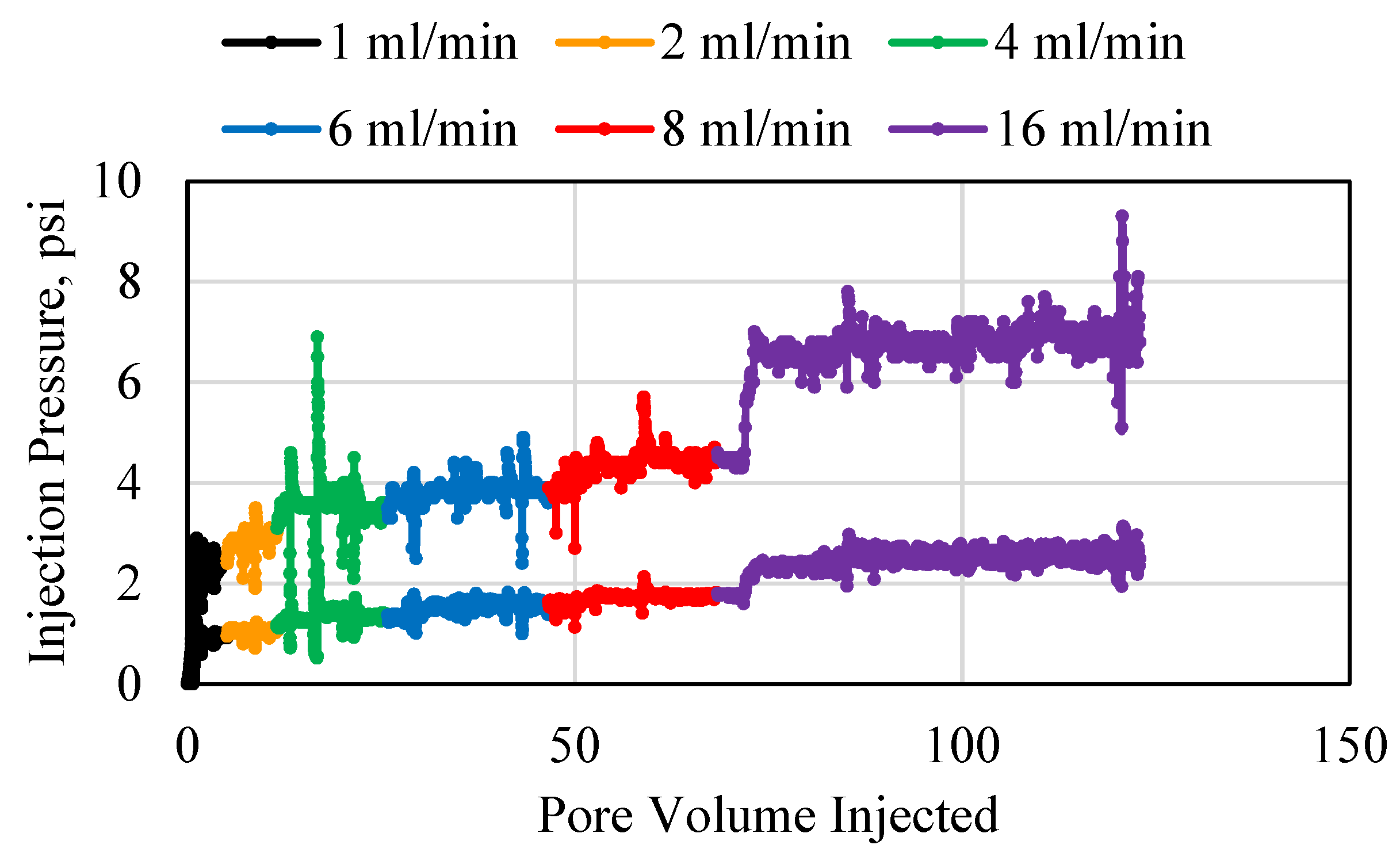

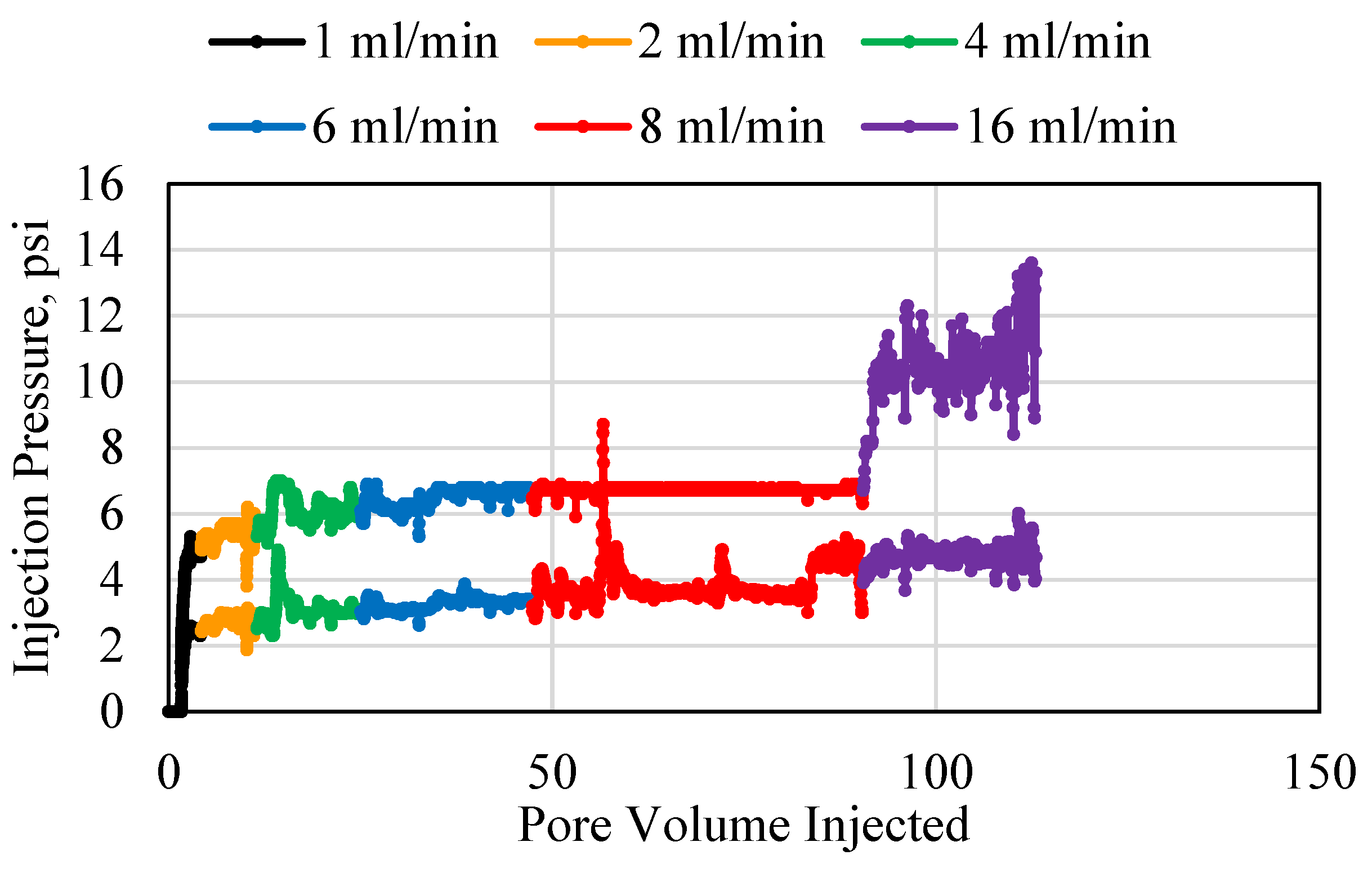

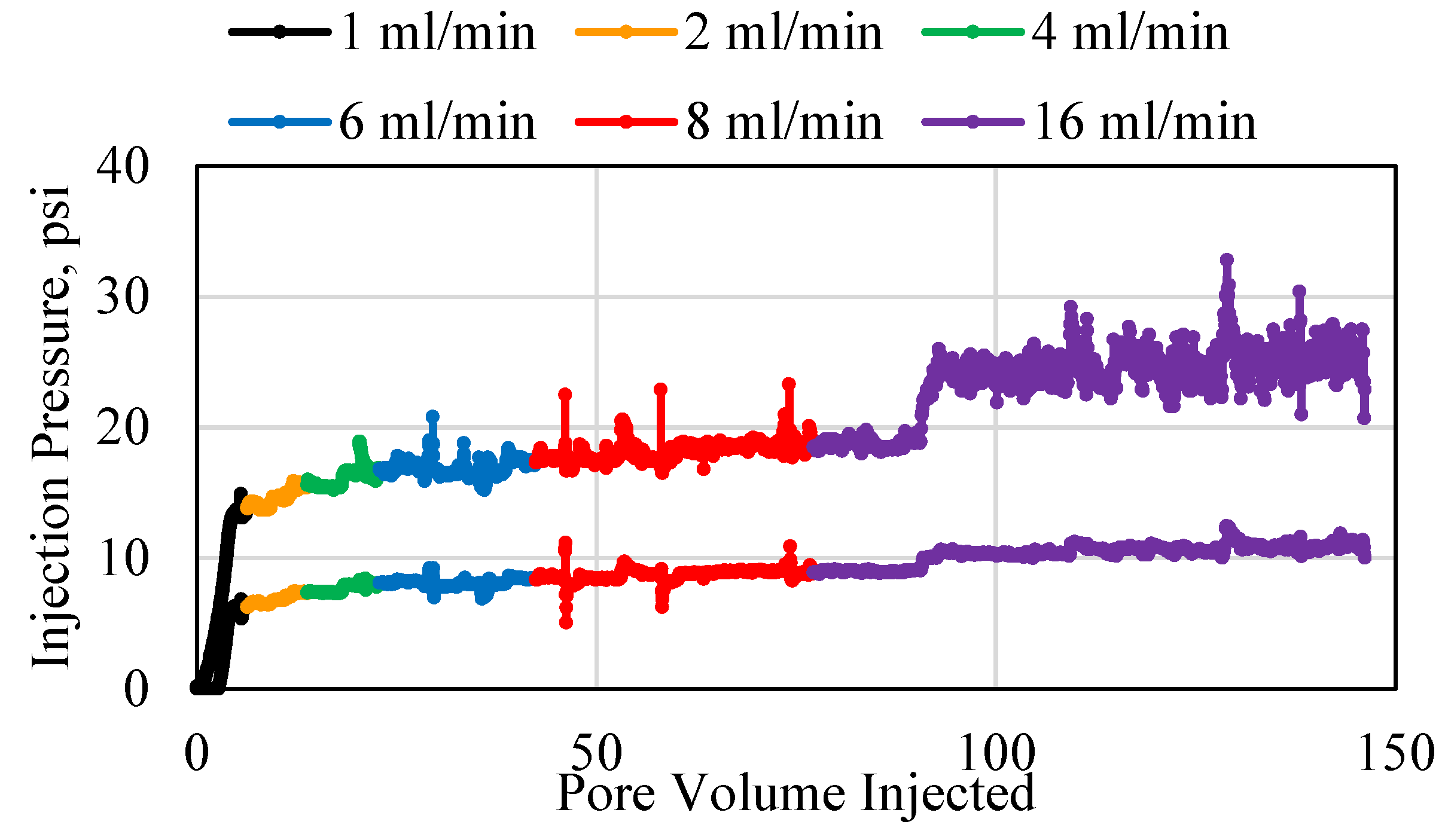

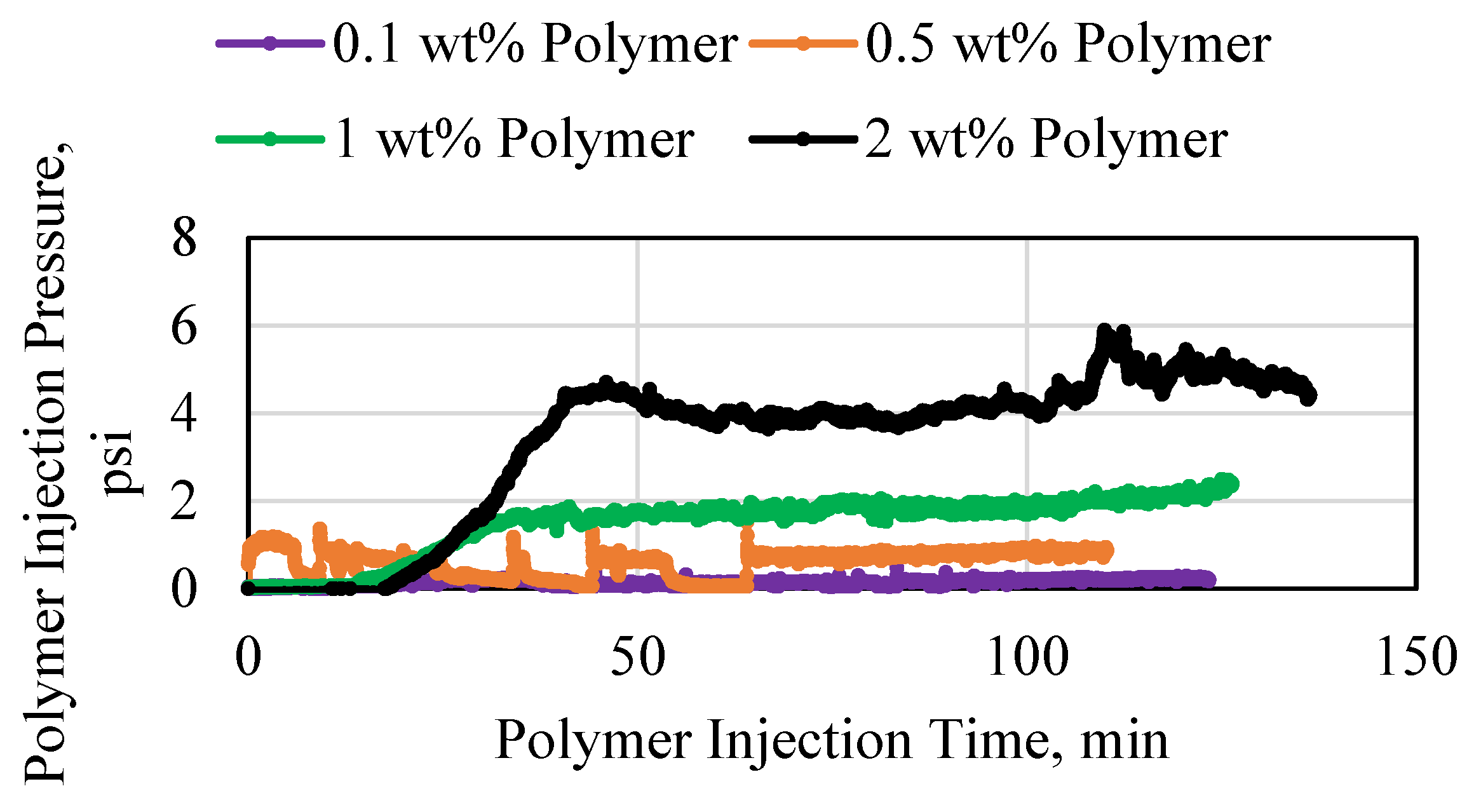

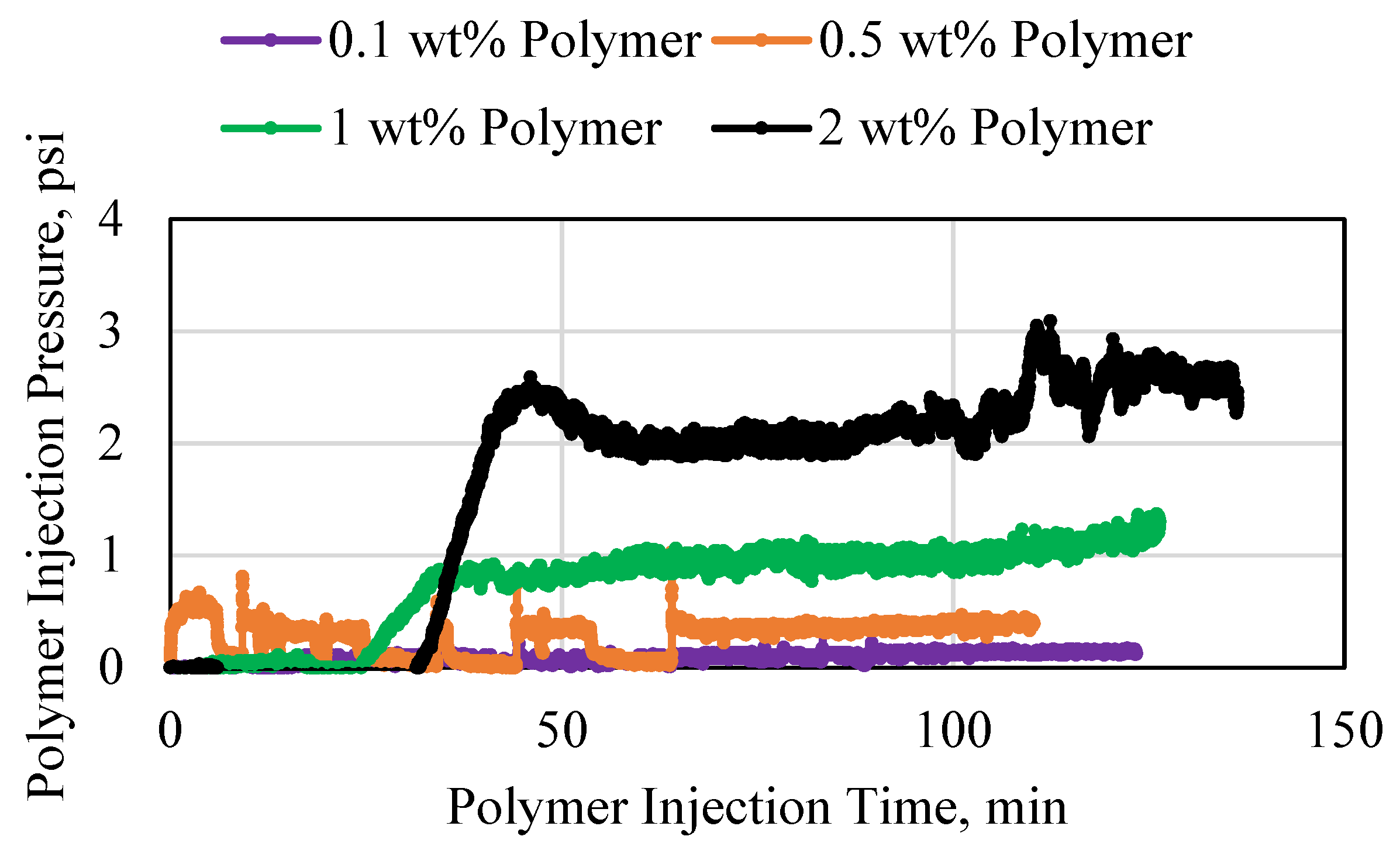

3.1. Polymer Injection and Injectivity

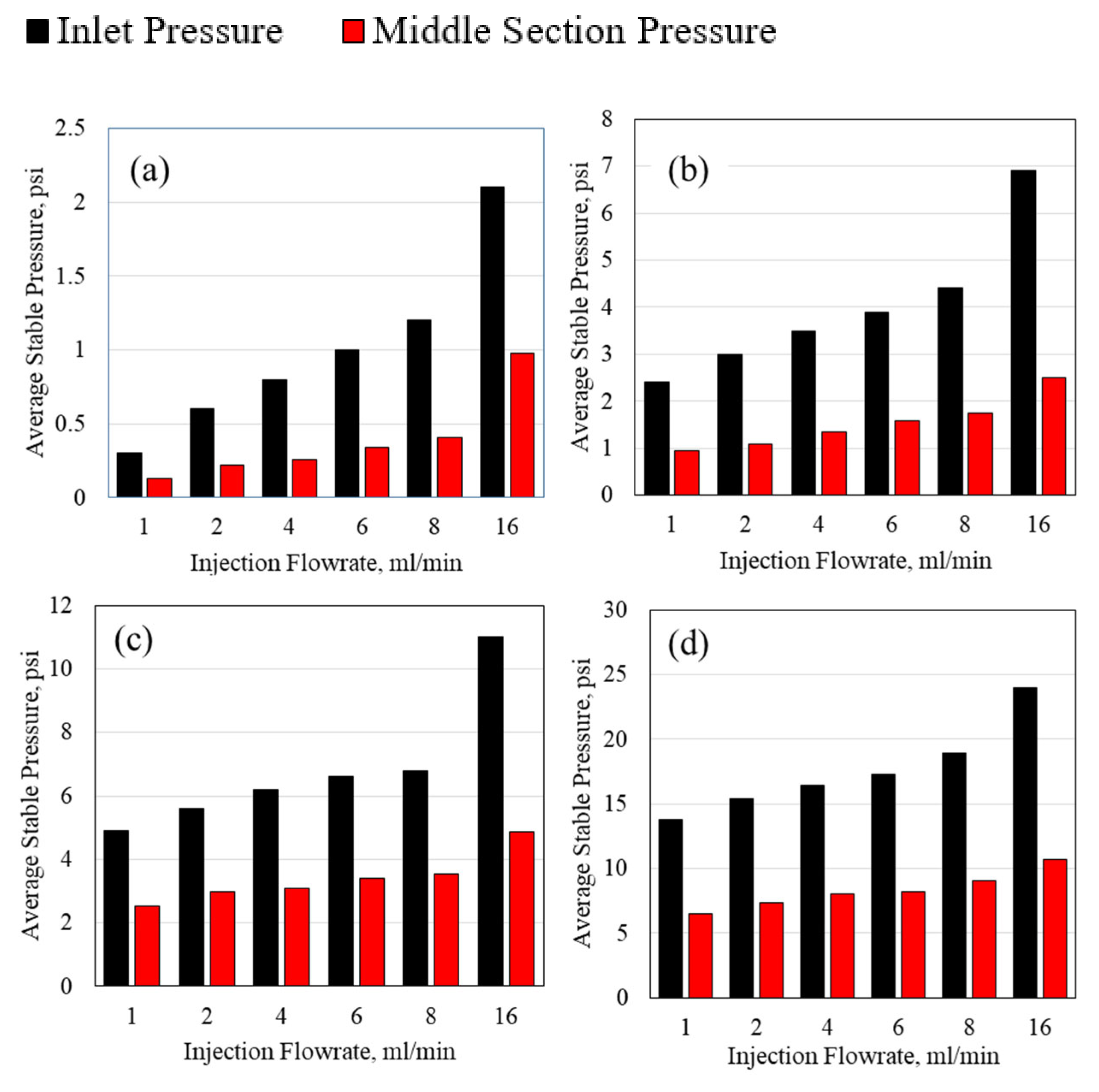

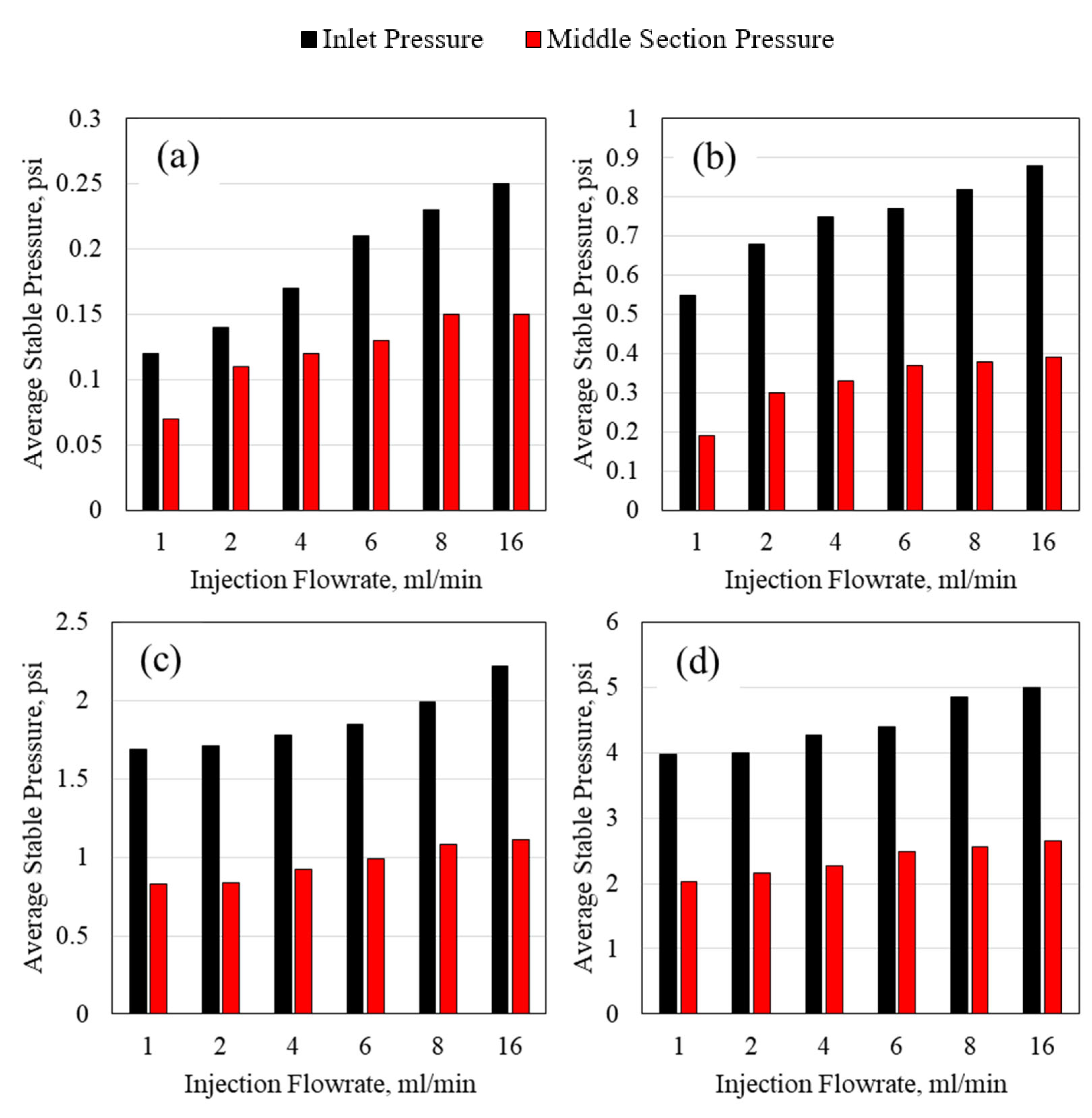

3.2. Polymer Average Stable Pressure

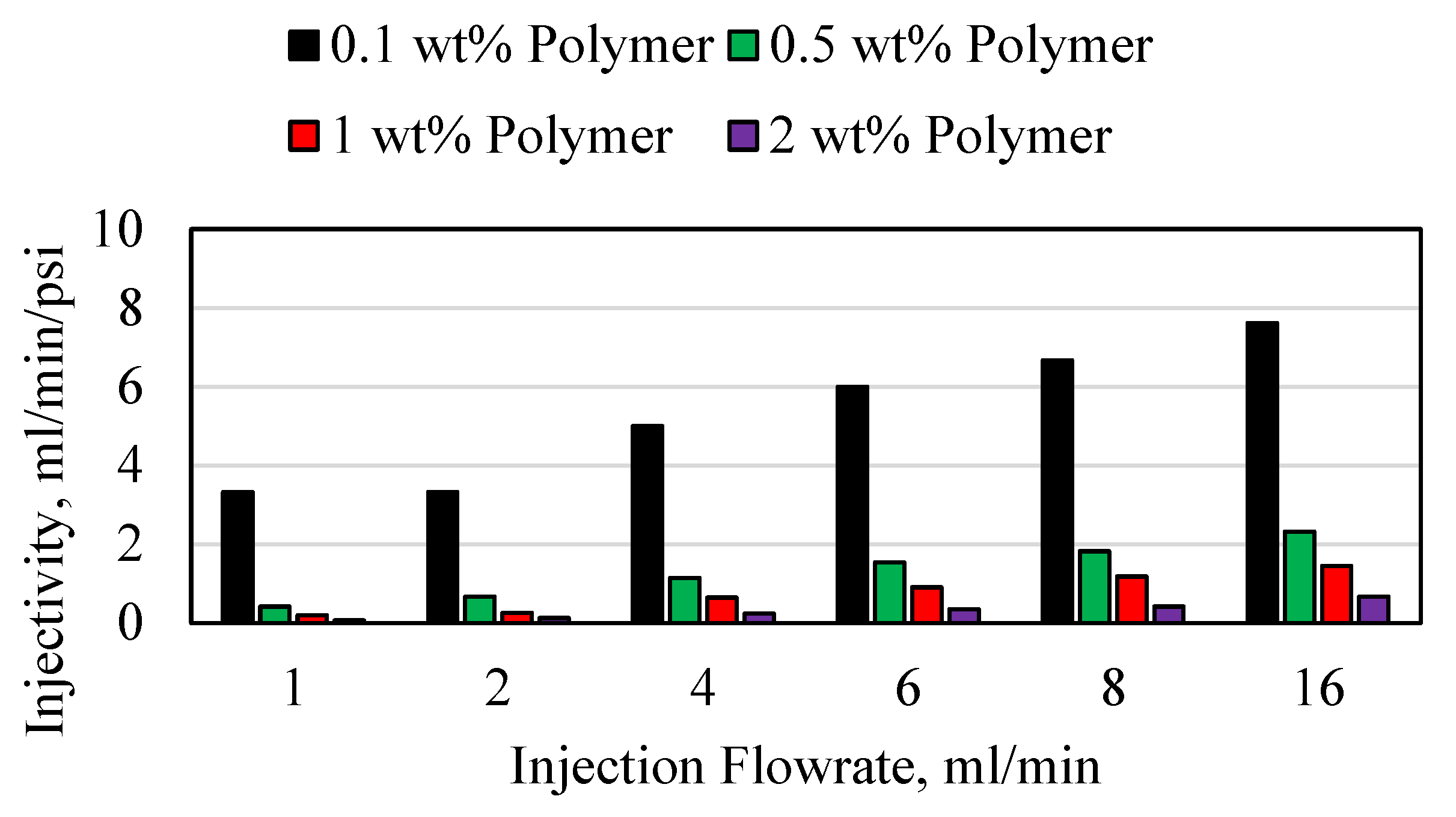

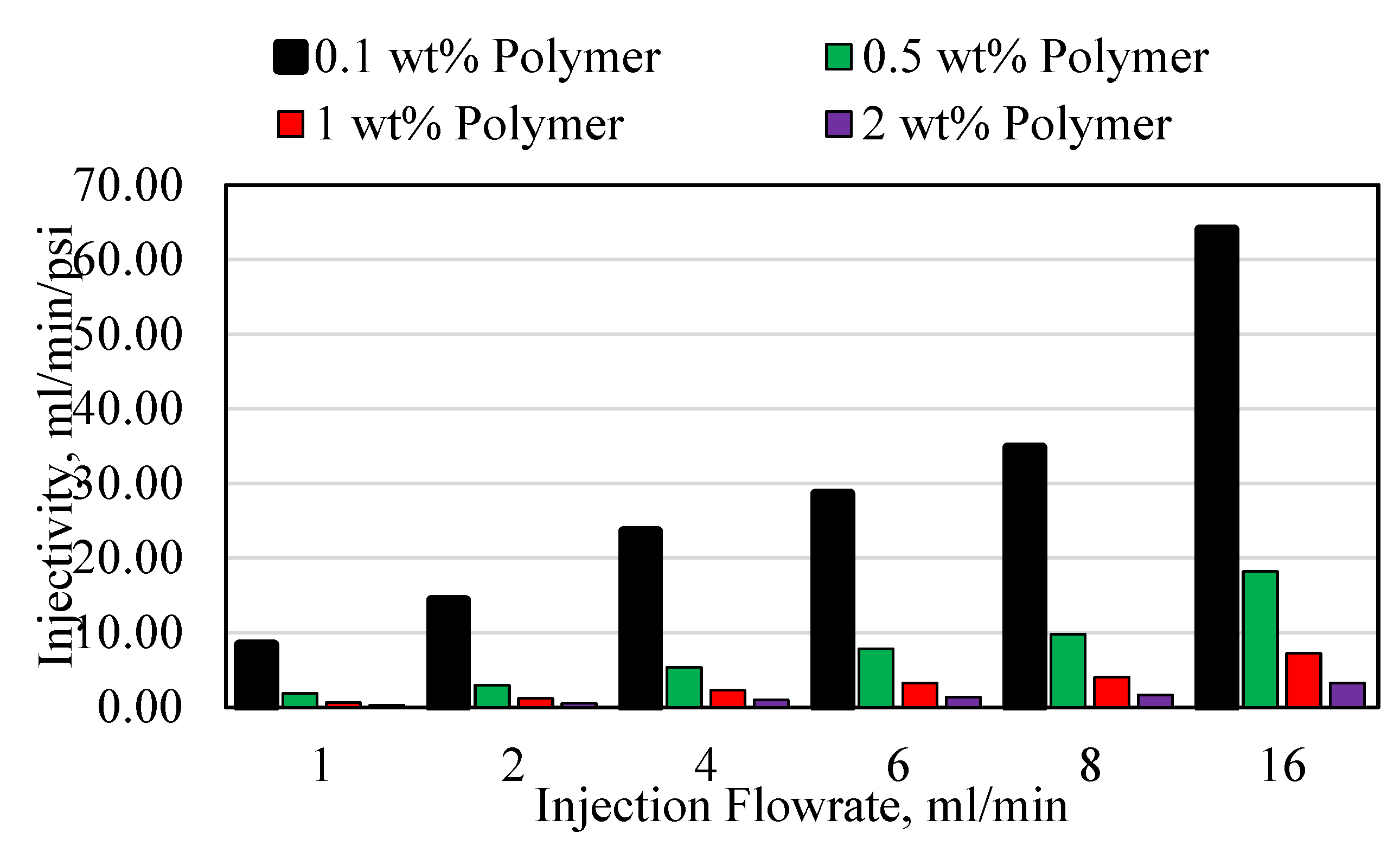

3.3. Polymer Injectivity

3.4. Polymer Degradation and Reinjection

4. Conclusions

- -

- Decreasing the pore size resulted in a significant decrease in injectivity and a significant increase in the pressure requirements for injection. This also resulted in a significant degradation in the polymer structure which caused the polymer to become a poor candidate for reinjection.

- -

- As the porous media length increased, the pressure required to inject the polymer also increased. This resulted in polymer degradation, which indicates that the length that the polymer travels is a governing criterion for polymer reinjection operations.

- -

- Polymer degradation is predominantly an irreversible process which indicates that if the polymer is structurally degraded, it has to be disposed which results in material loss and operational costs.

- -

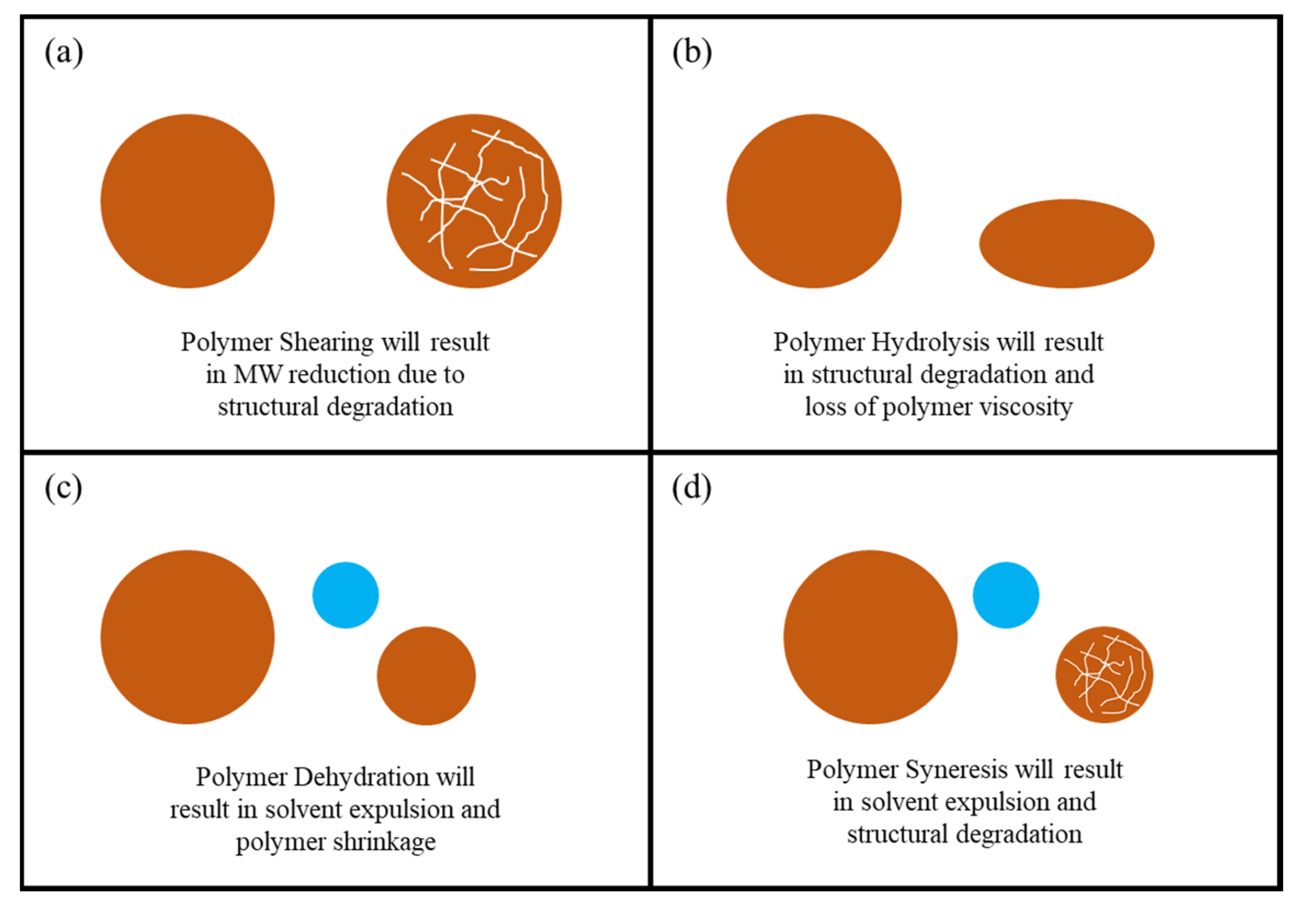

- Excessive polymer hydrolysis can result from high injection pressures and high shearing which can generate high temperatures, thus polymer hydrolysis is not only caused by reservoir temperature.

- -

- Polymer degradation decreases significantly with an increase in the porous media pore size, which indicates that polymer injected in the fractures due to the high fracture widths is less susceptible to degradation compared to the polymer injected into the formation matrix which usually has much smaller pores.

Statements and Declaration

References

- Alsofi, A. M., and Blunt, M. J. Streamline-Based Simulation of Non-Newtonian Polymer Flooding. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Baijal, S. K.. Interaction During Polymer Flooding. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1975.

- Bondor, P. L. et al. Mathematical Simulation of Polymer Flooding in Complex Reservoirs. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1972. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. et al. How Viscoelastic-Polymer Flooding Enhances Displacement Efficiency. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Delamaide, E. et al. Pelican Lake Field: First Successful Application of Polymer Flooding In a Heavy-Oil Reservoir. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Erincik, M. Z. et al. New Method To Reduce Residual Oil Saturation by Polymer Flooding. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kazempour, M. et al. Effect of Alkalinity on Oil Recovery During Polymer Floods in Sandstone. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, S. et al., 2020. Increasing Oil Recovery from Unconventional Shale Reservoirs Using Cyclic Carbon Dioxide Injection." Paper presented at the SPE Europec, Virtual, December 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, S. and Imqam, A., 2020. A data analysis of immiscible carbon dioxide injection applications for enhanced oil recovery based on an updated database. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 448. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, S. et al., 2019. A characterization of different alkali chemical agents for alkaline flooding enhanced oil recovery operations: an experimental investigation. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1622. [CrossRef]

- Khorsandi, S. et al. Displacement Efficiency for Low-Salinity Polymer Flooding Including Wettability Alteration. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Koh, H. et al. Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Polymers on Residual Oil Saturation. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Novosad, J. et al. Polymer Flooding In Stratified Cores. Petroleum Society of Canada, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Seright, R. S. et al. Injectivity Characteristics of EOR Polymers. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Seright, R. Potential for Polymer Flooding Reservoirs With Viscous Oils. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Seright, R. S. How Much Polymer Should Be Injected During a Polymer Flood? Review of Previous and Current Practices. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, S. et al., 2020. Carbon Dioxide Sequestration in Unconventional Shale Reservoirs Via Physical Adsorption: An Experimental Investigation." Paper presented at the SPE Europec, Virtual, December 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, S., 2021. What are the Dominant Flow Regimes During Carbon Dioxide Propagation in Shale Reservoirs’ Matrix, Natural Fractures and Hydraulic Fractures?." Paper presented at the SPE Western Regional Meeting, Virtual, April 2021. [CrossRef]

- Seright, R. S. et al. Can 25-cp Polymer Solution Efficiently Displace 1,600-cp Oil During Polymer Flooding? Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Seright, R. et al. A Comparison of Polymer Flooding With In-Depth Profile Modification. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J. J. et al. Status of Polymer-Flooding Technology. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Slater, G. E. and Ali, S. M. F. Simulation of Oil Recovery By Polymer Flooding. Petroleum Society of Canada, 1970. [CrossRef]

- Smith, F. W. The Behavior of Partially Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide Solutions in Porous Media. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1970. [CrossRef]

- Tagavifar, M. et al. Heavy-Oil Recovery by Combined Hot Water and Alkali/Cosolvent/Polymer Flooding. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. et al. Study of Alkaline/Polymer Flooding for Heavy-Oil Recovery Using Channeled Sandpacks. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. et al. Effect of Layering on Incremental Oil Recovery From Tertiary Polymer Flooding. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Baushin V. V., Muslimov R. K., Nikiforov A. I., Ramazanov R. G.. On oil recovery of fractured-porous formations during cyclic and polymer-cyclic waterflooding (Russian). Journal of Neftyanoe khozyaystvo - Oil Industry Journal (OIJ) 2023 (01): 40–43. [CrossRef]

- Kruglov D. S., Kornilov A. V., Tkachev I. V., Altynbaeva D. R., Sansiev G. V., Fedorchenko G. D., G. A. Fursov, D. M. Ponomarenko. Development of surfactant-polymer flooding technology for carbonate reservoirs with high salinity formation water and high reservoir temperature (Russian). Journal of Neftyanoe khozyaystvo - Oil Industry Journal (OIJ) 2023 (01): 44–48, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hu Guo, Zhengbo Wang, Sisi Dang, Rui Wen, Xiuqin Lyu, Huifeng Liu, Meng Yang. What is Learned from Polymer Flooding Practices in Offshore Reservoirs? Offshore Technology Conference May 1–4, 2023. Paper Number: OTC-32314-MS. [CrossRef]

- Khlaifat, A.L.; Dakhlallah, D.; Sufyan, F. A Critical Review of Alkaline Flooding: Mechanism, Hybrid Flooding Methods, Laboratory Work, Pilot Projects, and Field Applications. Energies 2022, 15, 3820. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Hou, Z.; Feng, G.; Liao, J.; Haris, M.; Xiong, Y. Effect of Reservoir Heterogeneity on CO2 Flooding in Tight Oil Reservoirs. Energies 2022, 15, 3015. [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, A.A.; Chughtai, S. Miscible CO2 Flooding for EOR in the Presence of Natural Gas Components in Displacing and Displaced Fluids. Energies 2018, 11, 391. [CrossRef]

- Hincapie, R.E.; Borovina, A.; Clemens, T.; Hoffmann, E.; Tahir, M.; Nurmi, L.; Hanski, S.; Wegner, J.; Janczak, A. Optimizing Polymer Costs and Efficiency in Alkali–Polymer Oilfield Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 5508. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, B.; Sun, S.; Hua, D.; Zhao, J. Laboratory Experimental Study on Polymer Flooding in High-Temperature and High-Salinity Heavy Oil Reservoir. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11872. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).