Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Influence of Gratitude on Adolescent Prosocial Behavior

1.2. The Mediating Role of Social Support

1.3. The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

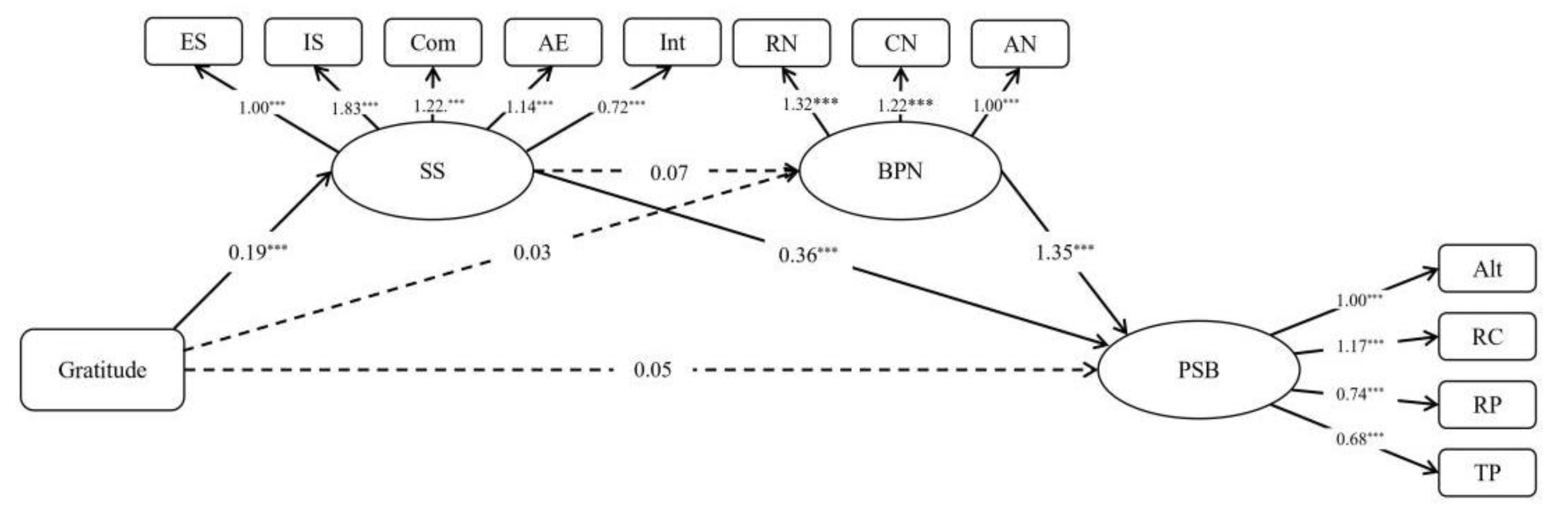

3.1. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenberg, N.; Morris, A. S. Children’s emotion-related regulation. In Advances in child development and behavior, Academic Press: San Diego, CA, US, 2002; Volume 30, pp. 189–229.

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T. L.; Knafo-Noam, A. Prosocial development. In R. M. Lerner, M. A. Easterbrooks, & J. Mistry (Eds.); Handbook of psychology; Developmental psychology, 2022; Volume 30, pp. 209–233.

- Froh, J. J.; Bono, G.; Emmons, R. Being grateful is beyond good manners: Gratitude and motivation to contribute to society among early adolescents. Motiv. Emot. 2010, 34, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. K.; Tunney, R. J.; Ferguson, E. Does gratitude enhance prosociality?: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 601–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, M. Y.; DeSteno, D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froh, J. J.; Bono, G. Gratitude in children and adolescents: Development, assessment, and school-based intervention. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.); Designing Positive Psychology: Taking Stock and Moving Forward. 2016, pp. 191–209.

- Wood, A.; Froh, J.; Geraghty, A. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M.; Kilpatrick, S.; Emmons, R.; Larson, D. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In The psychology of gratitude.; Series in affective science. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, US, 2004; pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K.; Lyubomirsky, S. The how, why, what, when, and who of happiness: Mechanisms underlying the success of positive activity interventions. In Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, US, 2014; pp. 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. The Relationship between Gratitude and Adolescents’ Prosocial Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirelli, L. K.; Einarson, K. M.; Trainor, L. J. Interpersonal interactions influence the perception of musical emotions in infants. Emotion. 2014, 14, 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J. M.; Baumeister, R. F.; DeWall, C. N.; Ciarocco, N. J.; Bartels, J. M. Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guzman, M. R. T.; Jung, E.; Anh Do, K. Perceived social support networks and prosocial outcomes among latino/a youth in the United States. Rev. Interam. Psicol. 2012, 46, 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, M. W.; Kret, M. E.; de Rooij, M.; van Honk, J. Giving behavior of adolescents: Intergenerational differences and the role of empathy and testosterone. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018, 9, 2483. [Google Scholar]

- You, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y. Relationships between gratitude, social support, and prosocial and problem behaviors. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 2646–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, V.; Unanue, W.; Gómez, M.; Bravo, D.; Unanue, J.; Araya-Veliz, C.; Cortez, D. Dispositional gratitude as an underlying psychological process between materialism and the satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs: A longitudinal mediational analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L. The need for competence. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T. K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L.; Ryan, R. M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M.; Maltby, J.; Gillett, R.; Linley, P. A.; Joseph, S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. J. Res. Personal. 2008, 42, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B.; Mishra, A.; Breen, W. E.; Froh, J. J. Gender differences in gratitude: Examining Appraisals, Narratives, the Willingness to Express Emotions, and Changes in Psychological Needs. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 691–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Self-Determination Research. ; Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Series Eds.; Handbook of self-determination research.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, US, 2002; pp x, 470. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R.; McCullough, M. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. H.; Chen, M.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-M. Does gratitude always work? Ambivalence over emotional expression inhibits the beneficial effect of gratitude on well-being. Int. J. Psychol. J. Int. Psychol. 2012, 47, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. K. Does gratitude mitigate the negative consequences of social support? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2012, 4, 386–407. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Zhang, X.; Huebner, E. The effects of satisfaction of basic psychological needs at school on children’s prosocial behavior and antisocial behavior: The mediating role of school satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, M.; Sheldon, K. M. The nature of motivational goals: A focus on self-determination theory. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and Action. 2015, pp 81–99.

- Leow, K.; Lynch, M. F.; Lee, J. Social support, basic psychological needs, and social well-being among older cancer survivors. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2019, 92, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, M.; Sheikholeslami, R.; Ahmadzadeh, M.; Cheraghi, A. Social support, basic psychological needs and psychological well-being: Examining a causal model in employed women. Dev. Psychol. Iran. Psychol. 2014, 10, 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, M. E.; Emmons, R. A.; Tsang, J.-A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H. Social support networks and peer relationships in middle school students. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science Edition). 1999, 1, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- La Guardia, J. G.; Ryan, R. M.; Couchman, C. E.; Deci, E. L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Q. P.; Kou, Y. The dimension of measurement on prosocial behavior: Exploration and confirmation. Sociology Research. 2011, 26, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M±SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | - | - | |||||

| 2. Age | 13.88±1.54 | .01 | - | ||||

| 3. Gratitude | 25.18±6.61 | .15** | .07 | - | |||

| 4. Social Support | 46.6±18.33 | .22*** | .02 | .39*** | - | ||

| 5. Basic Psychological Needs | 16.59±4.89 | .02 | -.09 | .22*** | .21*** | - | |

| 6. Prosocial Behavior | 7.54±17.63 | .12* | -.02 | .25*** | .34*** | .38*** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).