1. Introduction

It is estimated that one-third of the world's population has contracted hepatitis B virus (HBV), while 248 million are chronically infected, at risk of progressive liver disease [

1,

2]. Around 15 million people are reported to be coinfected with the hepatitis D virus [

3]. There is no accurate data regarding the epidemiology of HBV in Romania, but HBsAg prevalence is estimated to be high-intermediate, ranging from 5-7% [

2]. About 45% of the world's population lives in areas highly endemic to HBV, resulting in a lifelong risk of infection of 60%. Only 12% of the world's population lives in areas with a low HBV prevalence, with a lifelong risk of infection below 20%. In Romania, where the estimated prevalence is up to 7%, the lifelong risk of infection is 20-60% [

1,

3].

Regarding the consequences, one-third of the cases of liver cirrhosis and half of the cases of hepatocellular carcinoma are secondary to HBV infection [

3,

4]. Some patients with chronic HBV infection are reported to have developed antibodies [

5]. It is estimated that up to 40% of patients with HBV chronic infection will develop end-stage liver disease [

1], this being responsible for at least 600 000 deaths worldwide per year [

1,

4]. In 2015, 887 000 deaths occurred secondary to complications related to chronic hepatitis B [

6].

About 130-150 million individuals have hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The worldwide prevalence is estimated to be around 2-3% [

7,

8]. The World Health Organization estimates that every year 3-4 million individuals are infected with HCV [

9]. In the case of HCV infection, up to 85% of individuals subsequently develop a chronic infection [

7,

10]. About 40000 - 60000 children are born annually from HCV-infected mothers [

10,

11]. It is estimated that 1 million children are chronically infected worldwide [

1,

2]. In Romania, the prevalence of hepatitis C is approximately high-moderate, 2-5% [

8].

Because of the infection, 60-70% of patients with HCV will develop liver fibrosis and steatosis, up to 20% will develop liver cirrhosis, and up to 5% will develop hepatocellular carcinoma [

7]. Antinuclear antibodies, an essential marker of autoimmune hepatitis, included in the scoring systems for this disease, have been reported to have a higher incidence in patients with chronic HCV infection and show a worse prognosis [

12,

13]. It is estimated that about 350000 deaths occur annually, and 950000 individuals are permanently disabled secondary to chronic HCV infection [

10,

14].

Another issue reported in 80% of patients with chronic HCV infection is fatigue, unrelated to the severity of the liver disease, which alters the quality of life of these patients. Depression, cognitive impairment, delayed intellectual development, and learning deficits have also been reported to be associated. These events appear to be secondary to a virus-induced cerebral dysfunction [

10].

The burden of chronic viral hepatitis is high not only because of costs for prevention and treatment of the disease but also because of other costs, like absenteeism in school for children and in the workplace for parents, and low quality of life.

The aim of this paper was to approach the issues of chronic viral hepatitis interdisciplinary, taking into consideration the medical point of view but also the social and economic ones, because nowadays rapid changes are happening both in economy and society. Measuring economic and social aspects of this matter regards economic efficacy and social equity. Economic and financial mechanisms, social and sanitary policies may highlight measures for prevention and treatment to improve the health status of individuals. Financial opportunities and funds for chronic viral hepatitis are still insufficient.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a 4-year observational prospective study in the Pediatrics Department of "Grigore Alexandrescu" Emergency Children's Hospital in Bucharest, Romania. We included in the survey pediatric patients with chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Patients with other liver pathologies or uncertain aetiology of liver disease were excluded. After obtaining the parents' or legal guardians' consent, they were given a questionnaire to evaluate the child's socio-economic status. We gathered information about the geographical origin of patients (rural or urban area), whether the child was registered with a general practitioner and if the child was enrolled in school. Data regarding the family's income, the parent's level of education and employment status, data about the siblings and living conditions were also gathered. All data were processed using Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

3. Results

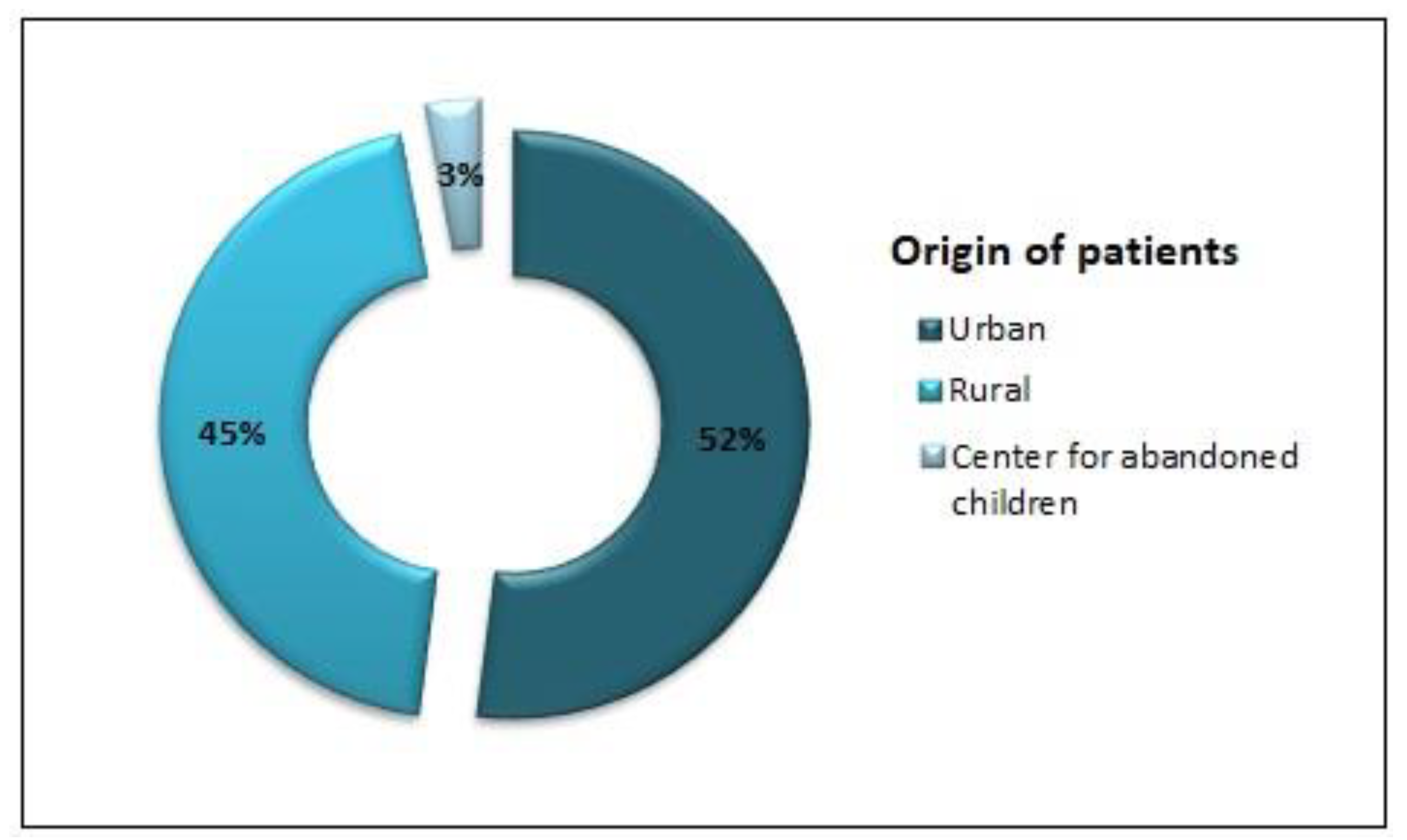

The inclusion and exclusion criteria identified one hundred and fifty-nine patients. The mean age was 103 months (8years 7months). Fifty-two per cent originated from urban areas, and 2.5% from centres for abandoned children (

Figure 1). All children were registered with a general practitioner. Out of 119 school-aged children, only 66% were enrolled. Families comprised 3 to 12 members (mean = 4.18, median = 4).

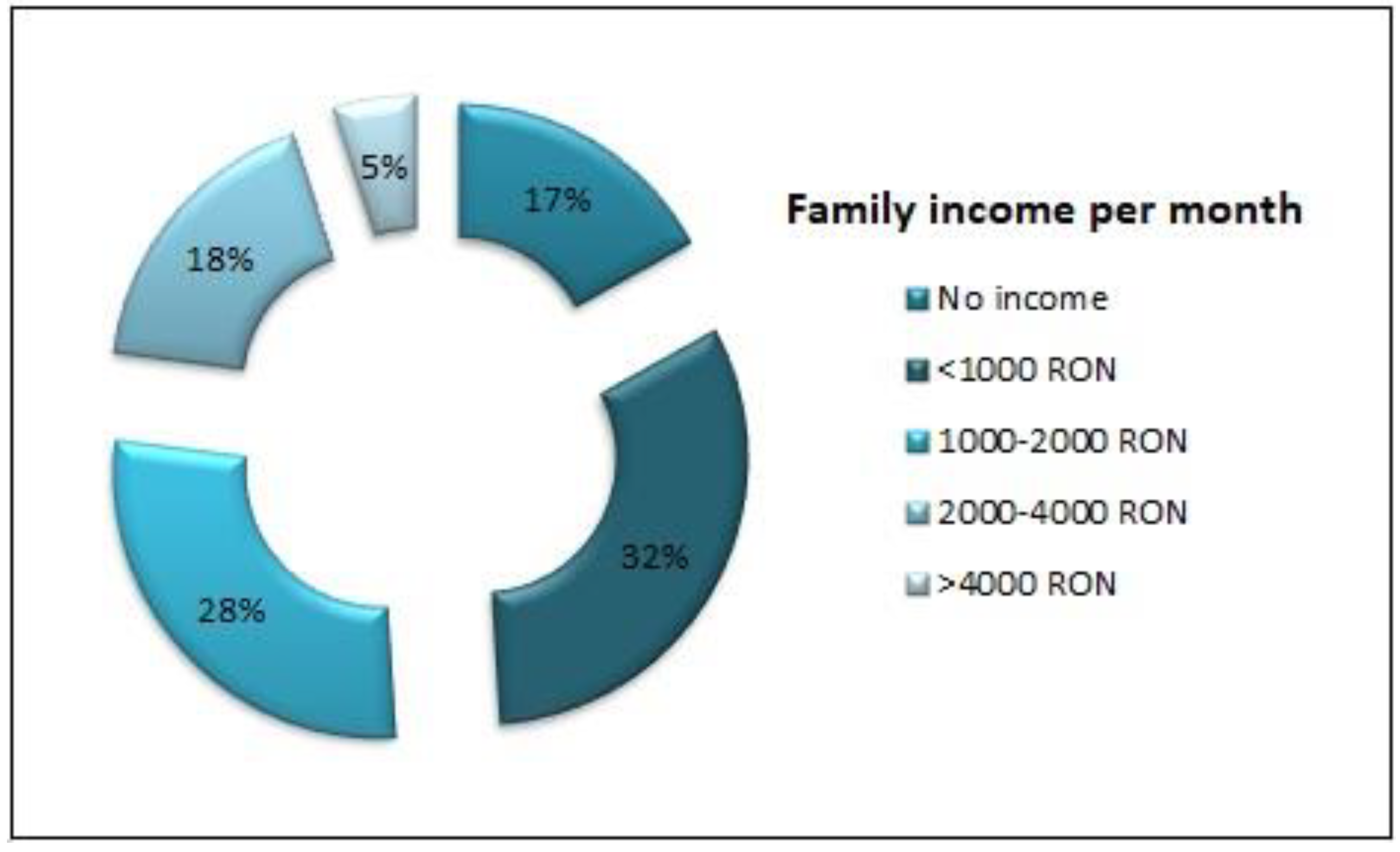

Seventeen percent of children came from families with no income, while most came from families with an income below 1000 RON per month. Only 5% of children came from families with a monthly income higher than 4000 RON. For one-third of children none of their parents had a work place. The monthly family income is depicted in

Figure 2.

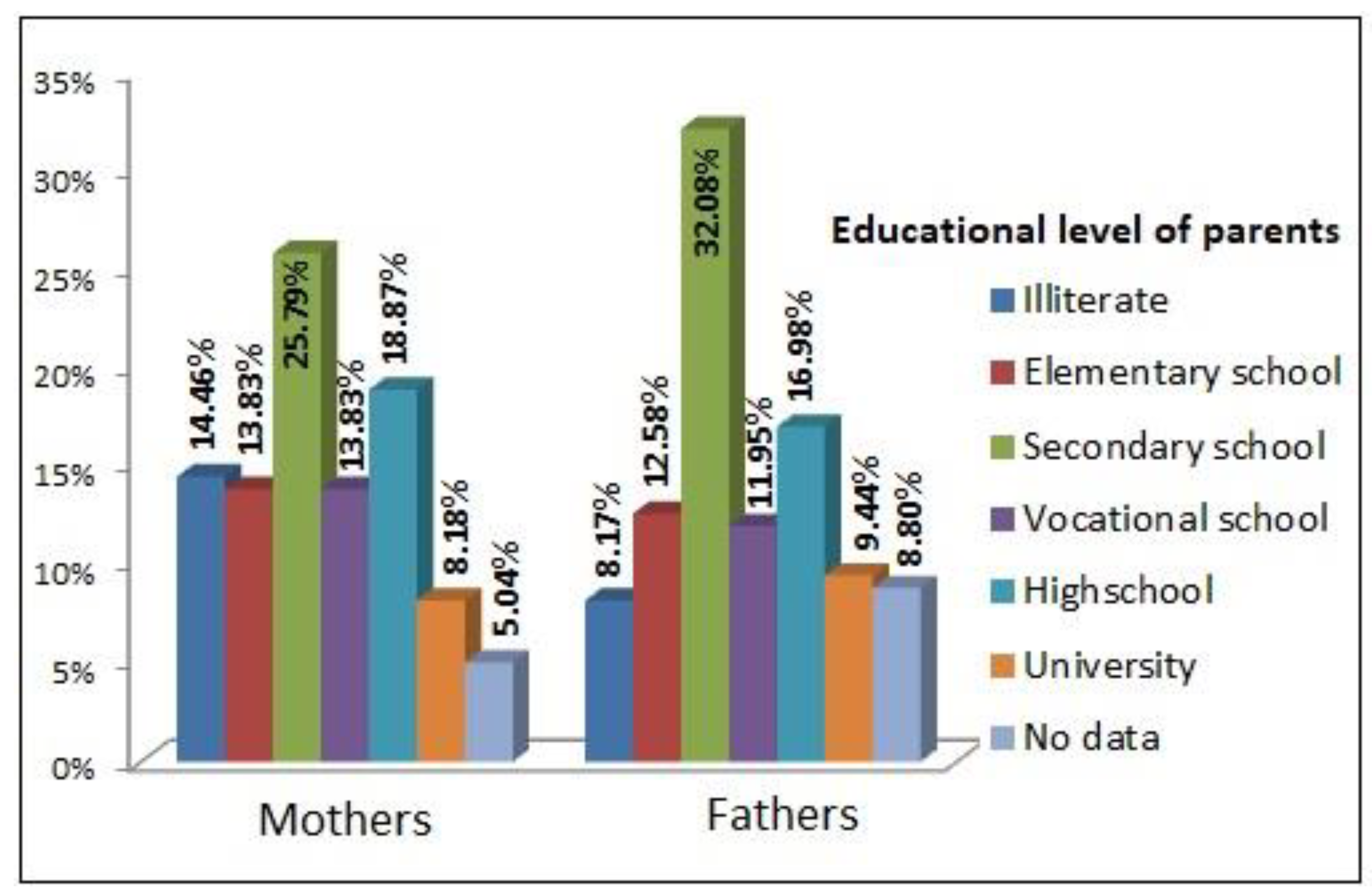

Regarding the educational level of the children's parents, the mean number of years of education was 7.8 for the mothers and 8.2 for the fathers, with a median of 8 for both mothers and fathers. For 17% of children, at least one parent was illiterate, while for 5.6%, both parents were illiterate. Only 8% of mothers and 9% of fathers had an academic degree. The education level of parents is presented in

Figure 3.

When analyzing the living conditions for the children included in the study, we found that the mean number of people in the household was 4.66 (median = 4), and the mean number of rooms per household was 3.22 (median = 3). The number of people per room ranged from 0.4 to 8 (mean = 1.8, median = 1.5).

Thirty-eight percent of the children in the study lived in households without sewerage and 23% without water facilities.

In 32% of cases, families reported sharing and cutting personal objects.

4. Discussion

Three years old was considered as the cut-off level for enrolment in early childhood education (International Standard Classification of Education 2011) [

15]. By this standard, out of 119 children above three years old, only 66% percent were enrolled in kindergarten or respectively school. This may be secondary to the low educational level of the family.

Regarding parents' educational level, for a significant number of children included in the study - 5.6% - both were illiterate, while for 17%, at least one parent was illiterate. Only about 9% of children originated from parents with an academic degree. Most children had parents with a medium to low level of education. In comparison to the last statement released by the National Institute of Statistics in 2011, this data suggests that parents of the children included in the study group had a lower educational level and a higher rate of illiteracy compared to the average level in Romania (1.4% rate of illiteracy, 14.8% individuals with academic degree) [

16]. The level of education is important for communicable diseases in terms of understanding and practising hygiene to limit transmission. Due to poor hygiene and overcrowding, these children have frequent respiratory or digestive infections, and thus they have high antibiotic consumption rates. Often symptoms are considered adverse effects of antibiotic therapy, and there are times when parents do not perceive important signs of illness, such as loss of appetite, failure to thrive or diarrhoea [

17,

18].

Lemoine et al. highlights the fact that mortality and morbidity through chronic hepatitis B are influenced by low vaccination rates, lack of education (which generates low access to information) and poverty. One of the determining factors causing malnutrition is poverty, due to an unbalanced diet, especially through lack of good quality proteins [

3,

19,

20]. The importance of a balanced diet and the role of proteins in maintaining a good nutritional status in the first year of life are well known. In an article published in 2016, Sahin Y et al. evaluated the prevalence of malnutrition among children with chronic hepatitis B. They concluded that additional information regarding the nutritional status of children is needed early during infection because timely interventions are imperative [

21,

22].

The abovementioned paper supports the data we report in this research; most children originate from families with a medium-low educational level. Lack of education leads to a neglecting attitude towards screening and prevention measures. Access to treatment also becomes an issue in this context [

3].

As to HCV, current publications display that prenatal screening is essential for implementing perinatal measures to prevent virus transmission to newborns [

10,

11]. The pursuit of screening depends on the mother's level of education. El-Shabrawi et al. highlight the need for health education and the importance of public awareness regarding HBV and HCV infection [

10].

According to the World Bank, Atlas method, Romania is considered to be a medium-high-income country, with a gross national income per capita of

$9970 per year (the equivalent of 3300RON per month), which is much more than the reported income for the study group enrolled [

23]. Seventy-seven percent of the children included in the study originated from families with an income below 2000RON per month.

Higher education may contribute to workplace occupancy, translated into income. Regular income offers security and protects against poverty. There are limited job openings for individuals with a medium-low education (secondary school at most), generating lower income and less security [

24].

The significant number of children living in improper conditions (no sewerage - 38%, no water facilities - 23%) may contribute to the risk of contagiously within these families. This problem is particularly poignant in the rural areas - only 17% of the rural settings and 8% of the rural households are reported to have water facilities, while in the urban areas, the percent rises above 85. Four percent of rural households have sewerage in contrast to 84% of the urban ones [

24]. In our study group, almost half of the children came from rural areas, justifying the numbers. We may also argue that rural areas surrounding Bucharest are more likely to have water facilities and sewerage in comparison to more isolated settings across the country.

Sharing of cutting objects (reported in 32% of the patients) may also increase the risk of transmission and is in direct correlation with the level of education (awareness of the disease and ways of transmission).

5. Conclusions

Socio-economic level can significantly impact disease epidemiology (infectiousness) and access to treatment for patients with chronic viral hepatitis. It is tightly related to educational level and access to information, which are critical factors in disease prevention through general and specific measures and disease management (treating infected patients and limiting transmission). Poverty and lack of education lead to late diagnosis of the disease, neglect and postponement of treatment, which add to the severity of the disease through morbidity and mortality. Prenatal screening also depends on the mother's level of education and is essential for preventing vertical transmission of the virus. There is a critical need for health education to raise people's awareness regarding viral hepatitis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D, A.C. and A.D.; methodology I.D, A.C. and A.D.; validation I.D, A.C. and A.D.; formal analysis, I.D, A.C. and A.D.; investigation, I.D, A.C. and A.D.; resources, I.D, A.C. and A.D.; data curation, I.D, A.C. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and A.D.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, I.D.; project administration, I.D, A.C. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

"The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Grigore Alexandrescu Children's Hospital (protocol code 19412/12.12.2013)".

Informed Consent Statement

"Not applicable."

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

"The authors declare no conflict of interest."

References

- Hwang E, Cheung R. Global Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection. North American Journal of Medicine and Science, 2011; 4(1): 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Averhoff F. (2017, June 13). Hepatitis B. Retrieved from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/hepatitis-b#5182.

- Lemoine M, Thursz M, Njie R, Dusheiko G. Forgotten, not neglected: viral hepatitis in resource-limited settings, recall for action. Liver Int, 2014; 34(1): 12-5.

- Shepard C, Simard E, Finelli L, Fiore A, Bell B. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol Rev, 2006; 28: 112-25.

- Pop T, Stefanescu A, Samasca G, Miu N. Clinical significance of antinuclear antibodies in chronic viral hepatitis B in children. Clin Lab, 2014; 60(6): 931-9.

- World Health Organization (2018, July 18). Hepatitis B. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

- Ansaldi F, Orsi A, Sticchi L, Bruzzone B, Icardi G. Hepatitis C virus in the new era: Perspectives in epidemiology, prevention, diagnostics and predictors of response to therapy. World J Gastroenterol, 2014; 20(29): 9633-9652. [CrossRef]

- Holtzman D. (2017, June 12). Hepatitis C. Retrieved from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/hepatitis-c.

- Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis, 2005; 5(9): p. 558-567. [CrossRef]

- El-Shabrawi MH, Kamal NM. Burden of pediatric hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol, 2013; 19(44): 7880–7888.

- Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, Rahman B, Guise JM. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med, 2013, 158(2): 109-113. [CrossRef]

- Costa de Castro GL, da Silva Graça Amoras E, Araújo MS, Souza da Silva Conde SR, Araújo Bichara CD, Freitas Queiroz MA, Rosário Vallinoto AC. High prevalence of antinuclear antibodies in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection, Eur J Med Res, 2022; 27: 180.

- Nita AF, Pacurar D. Adequacy of scoring systems in diagnosing paediatric autoimmune hepatitis: retrospective study using a control group children with Hepatitis B infection. Acta Paediatrica, 2019; 108(9): 1717-1724. [CrossRef]

- Kretzer IF, Do Livramento A, Da Cunha J, Goncalves S, Tosin I, Spada C, et al. Hepatitis C Worldwide and in Brazil: Silent Epidemic—Data on Disease including Incidence, Transmission, Prevention, and Treatment. The Scientific World Journal, 2014; 827849.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2012). International Standard Classification of Education. Retrieved from: http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced.

- Institutul National de Statistica (2011). [Recensamantul Populatiei si Locuintelor]. Retrieved from: http://colectaredate.insse.ro/phc/aggregatedData.htm.

- Becheanu CA, Tincu IF, Smadeanu RE, Coman OA, Coman L, Tincu RC, Pacurar D. Benefits of oligofructose and inulin in management of functional diarrhoea in children - Interventional study. Farmacia, 2019; 67(3): 511-516.

- Becheanu CA, Smadeanu RE, Tincu IF. Effect of a Symbiotic Mixture on Fecal Microbiota in Pediatric Patients Suffering of Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders. Processes, 2021; 9(12): 2157. [CrossRef]

- Gerner P, Hörning A, Kathemann S, Willuweit K, Wirth S. Growth abnormalities in children with chronic hepatitis B or C. Adv Virol, 2012; 670316. [CrossRef]

- Tincu IF, Pacurar D, Tincu RC, Becheanu C. Influence of Protein Intake during Complementary Feeding on Body Size and IGF-I Levels in Twelve-months-old Infants. Balkan Medical Journal, 2020; 37(1): 54-55.

- Şahin Y. Prevalence of malnutrition in children with chronic hepatitis B infection. Arq Gastroenterol, 2016; 53(2): 89-93.

- Becheanu CA, Tincu IF, Smadeanu RE, Lesanu G. Feeding Practices Among Romanian Children in the First Year of Life. Hong Kong Journal of Paediatrics, 2018; 23(1): 13-19.

- World Bank (2017). GNI per capita, Atlas method. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gnp.pcap.cd\.

- Paraschiv E. [Problema Sărăciei în comunităţile urbane şi rurale din România]. Revista Română de Sociologie, 2008; 3(4): 423-451.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).