Introduction

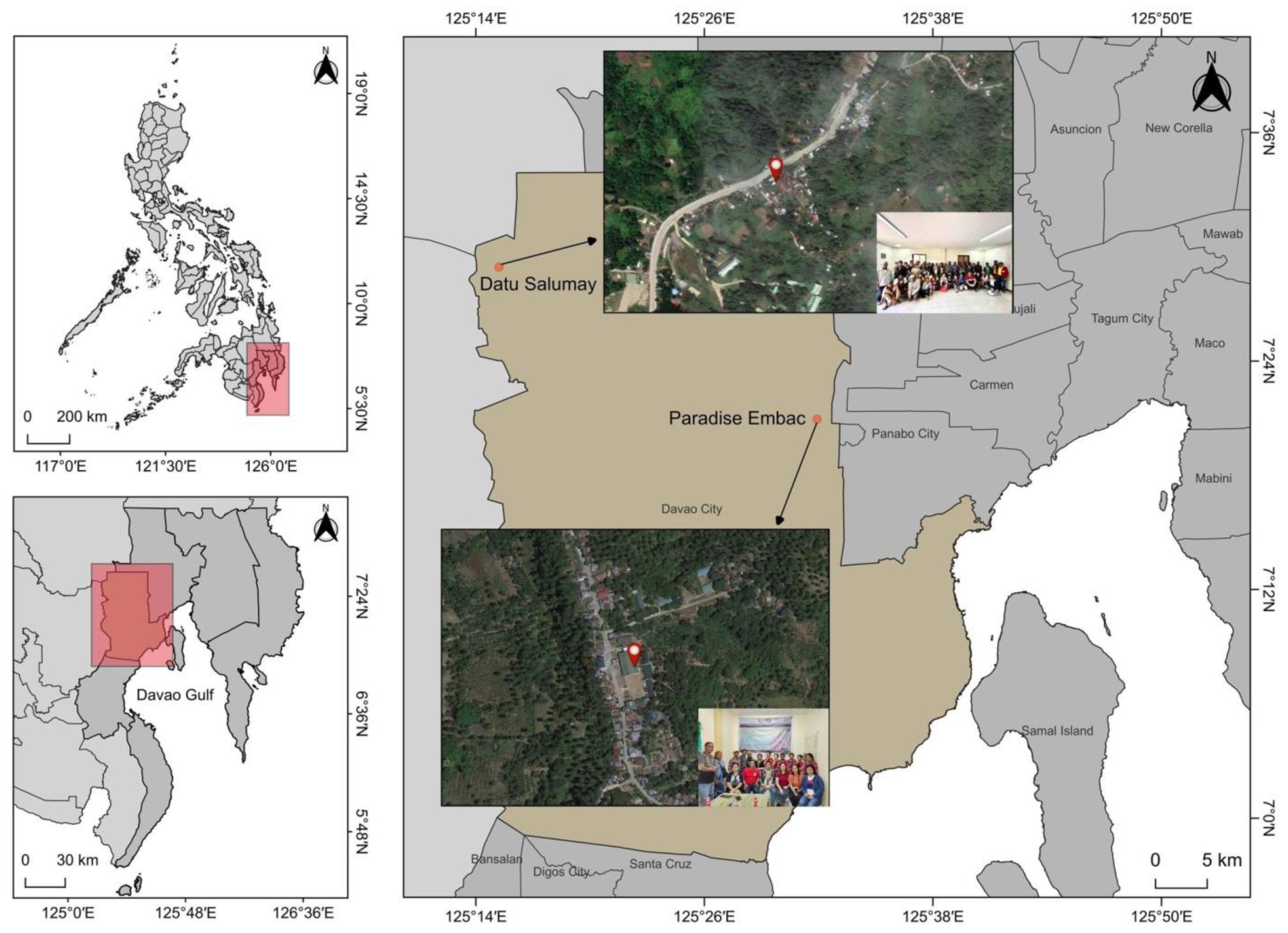

The Philippines is an archipelagic country consisting of 62 indigenous cultural communities (ICCs) spread across various islands. However, it appears that only since recently have these indigenous communities been given serious attention because of their existing indigenous knowledge systems and practices (IKSPs) and existing resources in their area. The promise of IKSP is with regards to food security and crop management such as food utilization, cultivation, and conservation practices which have been poorly acknowledged or documented in the scientific community. IKSPs refer to the skills, beliefs, knowledge, and philosophies developed by societies with long histories of interaction with their natural environments. It has been previously mentioned that IKSPs are beneficial in preserving the environment and the possible impact of their knowledge has many possible benefits towards generating new ideas. The IKSP of indigenous tribes have long been considered a comprehensive concept designed to assist and enhance the knowledge about techniques in terms of agricultural aspects, particularly in upland areas. Their methods in terms of farming are environmentally friendly which do not cause any stress to agricultural areas and mountain ecosystems (Marcogliese, 2008). In addition, IKSPs have a role in monitoring and managing ecosystem practices and functions with special attention to ecological resilience (Berkes et al., 2000 & Mendoza et al., 2022). The promotion of IKSPs in some areas has rendered communities to be productive in terms of income and their lands producing alternative livelihood resources such as native products and other commodities (Yazdanpanah et al., 2021). The IKSPs are beneficial to enhance our knowledge in terms of food security and crop management techniques as well as conservation practices for our upland environment (Manik et al., 2019). It is also useful to make an efficient decision regarding activities, such as agricultural and educational assistance, that are acceptable to the ICCs way of living (Corona & Derr, 2020). Hence, the documentation of IKSP of Matigsalog and Ata tribes will help create new information to develop sustainable solutions for a culturally acceptable livelihood (Berkes et al., 2000 & Zhong et al., 2022). By learning from the indigenous peoples’ knowledge system and practices e.g., on farming, livestock raising, fishing and conservation practices, this will help enhance environmentally safe and sustainable farming practices for our lowland communities in general (Hernani et al., 2021).

The cultivation and farming practices of indigenous tribes can be utilized to provide valuable information to promote and document the design of ecologically desirable farming production systems (Singh & Sureja, 2008). These practices come in various arrangements of crop management systems practices, such as home gardens, crop combinations in fields to the management of crop utilization, and cultivation practices like mixed fruits trees. This may not also only refer to their traditional local ecological knowledge (TEK) about native farming practices but also include their food production system (Heywood, 2011). Thus, this TEK of the tribes can be a good basis for agroforestry and crop practices that are sustainable and can be employed by many farmers. Crop production using their TEK can improve farm productivity due to its more conservative nature and therefore the ability to provide many ecosystem services (Martínez-Martí et al., 2020). However, there are currently very few existing agricultural practices that can be considered having sound sustainable practices that can be attained through simultaneous enhancement of agroecosystem diversity and farm productivity as in agricultural systems (Khan et al., 2019). There are only few studies in the Philippines that have considered looking into the contribution of TEK particularly with regards to food security and crop management to utilize agricultural sustainability and productivity (Akinnifesi et al., 2008) and address issues such as livelihood assessment, climate change and seasonality of crops (Nyong & Martin, 2019). The aim of this study was to document the indigenous knowledge systems and practices of the Matigsalog and Ata tribes in Davao City, particularly their special and unique agricultural techniques, rituals and practices regarding conservation, selection, and food utilization in the Davao region. Our second goal was to assess also their existing livelihood options and how the government can further benefit them.

Results

Livelihood and resources in the area

The common livelihood resources in the two areas are farming mainly of rice in Marilog district area and corn in Paquibato area. Interspersed in the cornlands are coconuts, marang, rambutan, durian, cacao, abaca, and coffee for the Ata tribes. They also plant camote,

carlang and squash. While for the rice farming area of Bukidnon, which is a mountainous area, this also includes vegetable, abaca and banana farming (

binangay, cardaba, tundan). They have planted rice with different varieties, but continue to plant native ones including denorado, pilit and azucena; while for corn, they planted a variety named

sige-sige, a loose term for hybrid corn but planted year after year like open-pollinated varieties in their area but they wanted to replant their areas with native corn varieties like Tiniguib. In both areas, they were highly affected by the decision of the Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) to stop buying their native abaca varieties, which they have been using for the longest time in the area, accordingly, because of poor fiber quality. They are advised to change and plant the

tanggungon abaca variety, an NSIC registered variety (see

Table 1).

In terms of aspirations, the Matigsalog tribe, wanted to have a dressmaking and bead-making cottage industries for their women’s group. They are requesting to have sewing machines and fabric that can be used to start up their own dressmaking and bead-making cottage industry. They also asked for more trainings regarding backyard raising of Tilapia and Hito, training on raising ornamental plants and provisions for horses and carabaos. Moreover, they do not grow ornamental crops, but they wanted to engage in this kind of livelihood because they have observed this from their Bisaya neighbors. Besides, the climate is favorable as well as there are diverse valuable ornamental crops existing in the area. In fact, they are sometimes the source of these ornamentals which they collect from their areas and mass propagated by the Bisayas.

Similar to the Matigsalog tribe, the livelihood resources found in Paquibato district are farming of fruit trees such as durian, lansones, breadfruit, rambutan, cacao, coffee, coconut, and abaca. They are also raising livestock such as goats, poultry, and native pigs, including ducks. Other crops cultivated include corn, squash, sayote, and ube. Thus, the Ata tribe from Paradise Embac also asked for livelihood such as egglayers, dressmaking and beadmaking, livestock, fishing implements like nets and gears to make a fishpond for Tilapia and grinding and pelletizing machine to make their own feeds (see

Table 2).

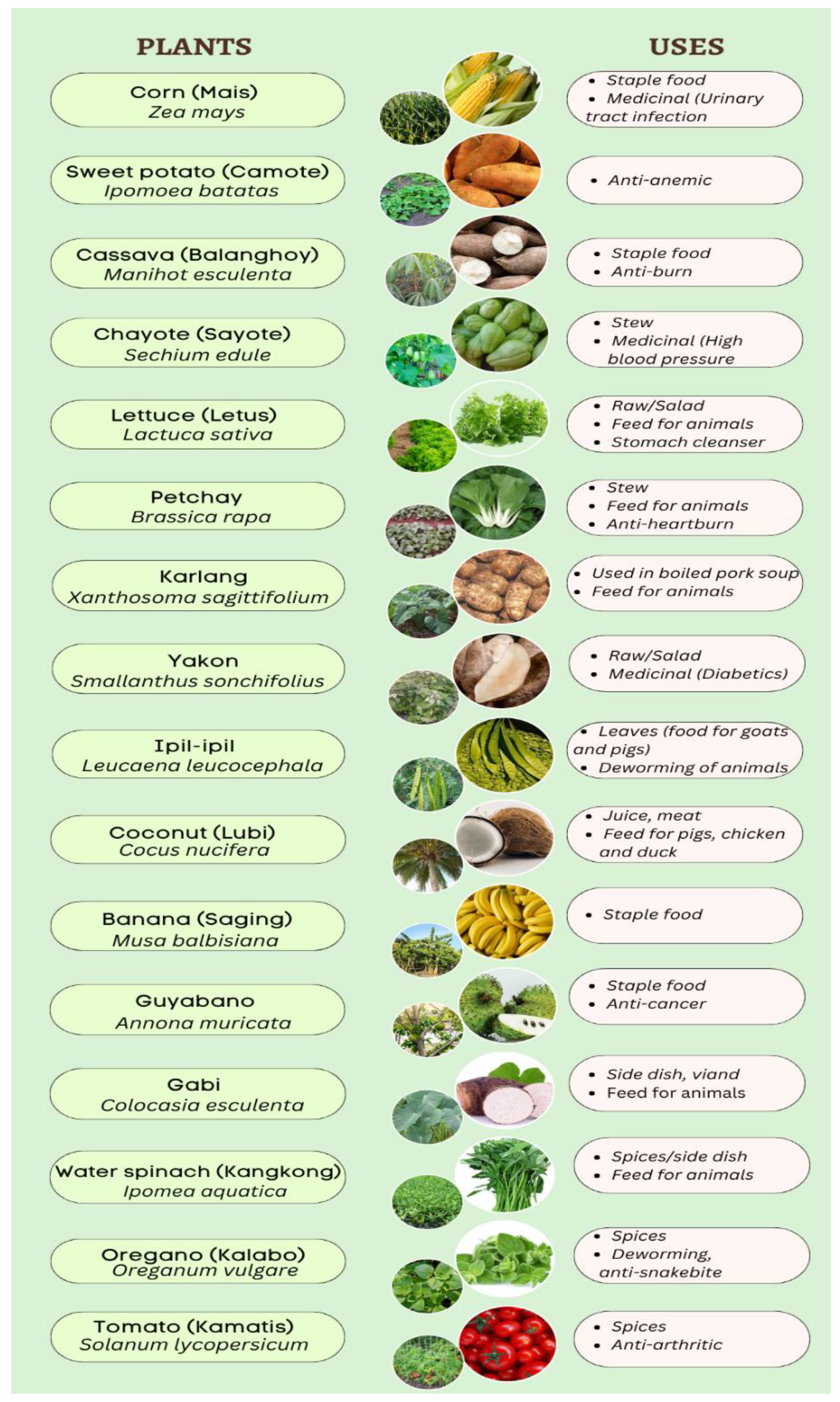

Different crops available in Marilog District and their uses

Based on the focus groups, the following crops were mentioned to be very useful as a staple food, sold as a root crop or traded by the farmers. Corn (Zea mays) is used in variety of ways, for instance, when grounded, it is used as a daily food staple, while the corn seeds too can also be used as feeds for chicken, fish (Tilapia) and the whole ear of a corn (pakaw) can be eaten by pigs. While the corn silk can be boiled and used as a tea for urinary tract infection. Another crop is sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) or camote, the young leaf (camote tops) can be used as a vegetable salad together with tomato and green mango, while the tuber can be boiled, grilled, or fried as food. The skin of the camote tuber can be used as a feed for pig, dogs and even for tilapia fish. In addition, camote tops can be boiled as food for anemic individuals.

In addition, the farmers also plant cassava (Manihot esculenta), where it can be used as food for snacks to make a cassava cake (suman), cassava sweets, or cassava flour, while the leaves of the plant can be used as food for horses; the leaves can be used for hot steam inhalation (tuob/suob). The root can also be used to cure burns. Sometimes termed as a green gold in Baguio City, the chayote (Sechium edule) plant has various uses including its young leaves as a vegetable salad or part of stew. The fruit with a shape of a pear is often added to be part of various meat dishes such as pork stew, as a side dish or can also be used as feed for pig, and chicken. Moreover, the chayote fruit can also be used as a cure for high blood pressure by juicing it. Another leafy vegetable grown and sourced in the area is lettuce (Lactuca sativa) which can be eaten raw or used as salad, part of other dishes or burger patties, it can also be used as food for pigs and the vegetable is known to cleanse the stomach. The stem can be used as a remedy for bruises (bali).

Pechay (Brassica rapa) is another leafy vegetable used in a variety of cook meals, it can be eaten boiled, steamed, part of a side dish or stews and it can also be used as food for pigs. It is a good remedy for those who are suffering heartburn. Another useful root crop is the karlang (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) which is often used in cooking usually as part of boiled pork meat or stews, sometimes the root crop can also be used as a food for pigs by boiling it first to make it soft. Upland rice, this is usually used as a staple food; darak from rice milling can be used as feed for pigs, chicken, and ducks.

Yakon (Smallanthus sonchifolius) is another root crop that can be eaten fresh or pickled, it can also be used as a feed for pigs and the leaves of the plant can be used as fodder for goats. Ipil-ipil plant (Leucaena leucocephala) is another useful plant in the upland areas, its leaves are utilized as food for goats, and the seeds can be used as antihelminth for animals.

Different crops available in Paquibato District and their uses

Corn (Zea mays) is also used by the Ata tribe as a staple food, the finely ground maize can be used to feed fish, chicken, and pigs while the dukot can be used for steamed inhalation. It can also be sold for commercial purposes.

Coconut (Cocus nucifera) is used in a variety of ways, it is sold as a copra, the juice can be drunk fresh, and the coconut shell can be used to make a charcoal that can be sold in the market. The coconut meat left overs (sapal) after grinding it can be used as a food for pigs and chicken, while the coconut milk is often used in cooking, the oil can also be used for healing and massaging purposes. In addition, it can also be used as a coconut coffee, with the meat being used for that purpose.

Banana (Musa balbisiana), it is often used in a variety of ways, mainly as additives in cooking for pig stew, snacks such as banana cue or pinaypay, fried banana as another snack variety and its young banana leaves can be used for enhancing breastfeeding purposes or for wrapping bruised areas in your body. The fruit is often sold immediately in the market.

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) or camote, can be used as a vegetable salad together with tomato and green mango, while the tuber can be boiled, grilled, or fried as food. On the other hand, the skin of the camote tuber can be used as a medicine for stomach upset or LBM by using the camote skin. Meanwhile for the Guyabano fruit (Annona muricata) can be used as staple fruit because the tree can grow fast, and once it starts producing fruit, it keeps producing throughout the year. Its young leaves can be used to feed the pigs and it can be boiled and made into a tea to be used for healing urinary tract infections.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta) is a root crop that can be used as food for snacks to make a cassava cake (suman), cassava sweets, or cassava flour, while the leaves of the plant can be used as food for horses; the leaves can be used for hot steam inhalation (tuob/suob). The root can also be used to cure burns.

Karlang (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) is used in cooking usually as part of boiled pork meats or stews, sometimes the root crop can also be used as a food for pigs by boiling it first to make it soft. It is a good remedy for those who look pale, lacks appetite to eat and anemic. Upland rice, this is usually used as a staple food; darak from rice milling can be used as feed for pigs, chicken, and ducks.

Gabi (Colocasia esculenta), leaf, stem and root tuber can be used as a food mixed with sardines or fish or with coconut milk. All parts of the plant can also be cooked through boiling and used as a feed for ducks, chicken, horses, pig, and goats.

Kangkong (Ipomea aquatica) is also used as a side dish and often cooked as adobo. When chopped, it can also be used as food for pigs.

Oregano (Oreganum vulgare), its leaves can be used as spices for cooking and can also be used for deworming of pigs and healing from snake bites.

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), its fruit is used as part of cooking spices and its leaves are used for treating wounds.

Figure 2.

Plants utilized by the two tribes in Marilog and Paquibato district of Davao City.

Figure 2.

Plants utilized by the two tribes in Marilog and Paquibato district of Davao City.

Seasonality and farming strategies of important crops

Upland Rice is a special crop to both tribes which involve four major crop production practices, lampas, pugas, guna and harvest period. Lampas is done during January to March (clearing for land preparation), and pugas (sowing/planting) occurs around March to May while guna (weeding period) is from May to June. Harvest time occurs from July to October. Both males and females are involved at all phases, but lampas or clearing is usually done by males. In terms of off-farm activities such as hunting wild pigs, these are usually around July for Matigsalog tribe. During the summertime, they are involved in construction jobs (March to April), while during May to July they are also working in the resorts. In the case of the Ata tribe, during off farm activities, the women are making dresses and beads. They have noted that rainy season starts from May to July and dry/drought period occurs during August to September, disease and pest attacks usually occur around May and June. While for the Ata tribe they noted that drought period occurs around March and April, and rainy season from May to July; rat infestation also occurs around the month of July. Harvest time is also around August to September. During post-harvest, they have a practice termed “Linaplapan” – this a postharvest processing in corn, where the corn is harvested at a specific stage, boiled with corn husk present, and then removed or “laplap” some outer part of the corn before being placed in containers or sacks and hanged for storage – this has important implications for their food security. These special storage containers are for rice, corn and useful for planting for the next season or for keeping the rice and corn for consumption. The special containers are usually made of the thick bark of lauaan tree which according to the respondents are bitter to pests.

Accordingly, the rituals for each major activity – both individual and community – denote their set of shared values which continue up to this day and which allow them to survive as a tribe. Moreover, the forest has a special function in the farming systems of the two tribes. For example, in Matigsalog tribe, they gather special “sagbot” or weed/plant from the forest to use for “palina”. These plants are broadcasted in the farm to protect the plants from diseases and pests. This also give them reason to protect the forest so ensure the survival of these plants.

Unlike the Matigsalog tribe, Ata men do not generally have off farm activities like labor for construction sites and mountain resorts. They do not need to resort to these activities as their produce is enough for their subsistence. On the other hand, the topography and cold weather in the Matigsalog area is attractive to lowland dwellers that is why many of them settled in Marilog district and made hillside residence and building establishments that require labor of the locals in the area. In addition, the Ata tribe do not have the usual problems associated with conventional rice farming – they do not need expensive fertilizers, no irrigation, and they are very knowledgeable in pest and disease management. In fact, they have special tools for persistent rice pests like rats and birds. The need to use agricultural inputs like fertilizers and pesticides for other crops like corn, vegetables, bananas, etc. because of the adoption of conventional farming practices. Settling down in one place and cultivating the same land again and again, made their cropping practices vulnerable to usual agricultural practices like soil infertility, susceptibility to pests and diseases.

Perception of climate change events

Both the Matigsalog and the Ata tribe have reported to have felt strong effects of climate change over the past decade. In Marilog Datu-Salumay, the Matigsalog tribe has observed an increase in frequency of droughts and floods, which have significantly impacted their harvest outcome. In Paquibato District, the Ata tribe has experienced strong winds that have damaged their upland rice plantations. They have also been affected by prolonged wet seasons, with heavy rains and floods. In addition, they mentioned the occurrence of heat waves in the years of 2013 to 2015 and frequent droughts.

Both tribes use the moon and star formations to predict the weather and the timing of farming activities. This technique is locally called “Pandorawa”. For “pugas” or sowing, they said it was best to sow when the moon is bright, and for “lampas”, it was best to do when they experience sunny weather. Furthermore, the tribes have a ritual of shaking to start the planting process; they call this “kalayat” or the sounds of white-eared (alimokon) to begin sowing the seeds from their land. According to members of the Matigsalog tribe, climate change and the accompanying change in weather conditions are affecting their abilities to accurately interpret the constellation of the moon and stars.

Another observation that was shared from recent years was the increase in occurrence of pests, both from rats and insects. The Paquibato District had been especially affected by rat infestation in the two consecutive years of between 2019 and 2021. To the question of the suspected origin of this problem, the Matigsalog tribe replied that they believed that this development was due to the change in cultural practices of surrounding farmlands, such as increased use of pesticides and fertilizers. The infestation of pests has had detrimental effects on the quantity and quality of the two tribes’ harvest yields. According to the Matigsalog tribe, their members usually possess the ability to predict the timing of pest infestation. However, they claim that these visions are inhibited due to the effects of climate change.

Climate change impacts on livelihood and aspirations for well-being

Being one of the area’s main upland rice producers, the decrease in harvest yield has a strong effect on the Matigsalog’s livelihoods as well as their subsistence. Some of the FGD members have expressed a general feeling of exhaustion towards the increased efforts to uphold their crop production, while others have offered testimonies of their acceptance of the overall situation and their willingness to adapt and become more resilient in consideration of climate change. It has also been mentioned that the tribes have observed a decline in health because of climate change. The Ata tribe has called this a “fever”, where they are suffering from the sun’s heat during the day, which makes even the early hours of the morning seem like the sun is at its zenith.

In more technical terms, the members of the Matigsalog tribe shared their aspirations to receive more assistance from the government, especially in the field of transportation of their products. Currently, they are delivering their harvest by foot over long distances through the mountainous area. In order to increase the efficiency of their trade and also minimize the physical exhaustion to their members, the tribe wishes for the supply of horses for transportation of goods as well as the provision of technical tools for their farming activities. Previous government interventions in Paquibato District have been evaluated as inefficient by the local tribe. During an especially dry and hot period, the government had wanted to provide the Ata IP with cacao seedlings. However, this support was not seen as an appropriate measure, as the Ata tribe felt a stronger need to purchase rice for subsistence at the time.

On the other hand, the Ata tribes have complained about corruption regarding budget allocation to their community. According to their leader, their community was included in the budget but have not received the allocated funding. Nevertheless, Datu Boyson said they were enhancing their practices to maintain ecological balance for the sustainability of their environment just as their ancestors have done. There is a continued demand for help and assistance funds by the government, specifically the National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP) as the authority to market their products so that they can manage their income independently and the earnings will not be lost to traders in Davao City and other investors.

Climate change adaptation strategies

In Marilog Datu-Salumay, the tribe members have developed several adaptation strategies in response to climate change, including intercropping; alternation of planting crop species that are resilient to either rainy season or drought season; and the increased use of fertilizer. Additionally, they grow “lagutmon” such as karlang, gabi, and gulay to avoid the rainy season because these crops can be harvested in just 45 days.

In Paquibato District, the first response to climate change was an adaptation of the daily rituals of the community’s farming practices. They perform more frequent prayers and rituals for protecting their environment and for sustained income on their farm. Moreover, they practice seed preservation and crop cultivation under forest rehabilitation and establish a massive nursery to restore their farmland, maintain their watershed protection areas and combat the impacts of climate change. The tribe has stationed 60 forest guards to secure their territory as well as the possession of a Certificate of the Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) and Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan (ADSDP). In addition, the community has started deforestation programs of foreign species to rehabilitate endemic trees. Lastly, some members of the community have abandoned their farmland to look for alternative labor and income to support their families.

Discussion

Livelihood aspirations

This study showed that the two tribes have contributed to farming cultivation and utilization in their communities. The abundance of their harvest through their farming efforts is essential to their daily survival and for other livelihood opportunities. It could be shown that indigenous knowledge can play a vital role in designing sustainable use of biodiversity and sustainable agricultural systems in which rural populations develop and maintain innovations and interventions through their experiences (Singh & Sureja, 2008). Some indigenous communities engage in small-scale agriculture as a source of income which has been demonstrated by the two tribes. They may cultivate cash crops such as coffee, cacao, and bananas, which have market value. On the other hand, they may participate in local markets and engage in value-added activities such as processing and selling traditional food products or handicrafts made from agricultural materials. In most parts of their ecosystems in the past, as local farmers in their communities, they have been in perfect harmony with nature and have substantially contributed to conserving the richness of their agrobiodiversity. This unity includes growing diverse crops with livelihood and livestock using on-farm natural resources to enhance the fertility of soils and resist crop pests (Ajibade, 2003). Regarding livelihood interventions, indigenous communities often have well-established practices prioritizing sustainability, cultural values, and community well-being (Galang & Vaughter, 2020).

Regarding additional farming crops and livelihood aspirations, the tribes requested for technical training on proper banana propagation, proper abaca propagation and proper fish culturing techniques and feed formulation using locally available raw materials. For traditional dressmaking, they need sewing machines and tools to finish bulk orders faster than stitching by hand. In order to pass this skillset through generations, they also need additional training on tailoring techniques and patternmaking to enhance their competency and train young women in the tribe to develop their sewing artistry. For bead making, they also want supplies of input materials to produce various accessories and quality beadwork and to start with their cottage industry in the area.

Crop management and utilization

The study showed that the two tribes have similarities in terms of plants that they utilized specially rice and corn, and root crops such as cassava, sweet potato (camote), abaca and banana and inland fisheries. They are also using traditional methods of planting upland rice and corn and perform rituals for each production activity.

The two indigenous communities rely on the crops grown in their area for their food security and survival (Bisht, 2020). These crops provide essential nutrients and form the basis of their traditional diets. However, indigenous tribes have a vast knowledge of medicinal plants and herbs in their local environment. They utilize various crops for conventional medicinal purposes to treat common disorders, illness and maintain health condition. During our validation, herbal remedies from plants in their community include guava leaves, lagundi, ginger, and turmeric.

On the other hand, crops play a significant role in the cultural and ritual practices of indigenous tribes. As they said, they are used in ceremonies, festivals, and significant life events. For instance, certain crops may be offered as part of ancestral rituals, weddings, or harvest celebrations, symbolizing attitude and respect for the land and nature (Hobbs, 2007). Also, the two tribes showed that traditional crop varieties adapted well to local conditions over generations. They actively engage in seed-saving and exchange practices, preserving these crop varieties and ensuring their availability for future planting seasons. This helps maintain crop diversity and resilience in the face of changing environmental conditions (Sanni et al., 2022). During the site visit, the two tribes have shown their planted farms in Datu, Salumay, Marilog District, and Paquibato District to be practicing sustainable farming techniques that promote soil health and biodiversity. They often employ traditional methods such as shifting cultivation, intercropping, and crop rotation. These techniques enhance soil fertility, reduce pest and diseases pressures, and promote natural resource conservation (Lohri et al., 2017).

Climate change adaptation strategies

The importance of traditional practices for the development of adaptation strategies is high, as it is built from knowledge passed down through many generations (Nelson et al., 2019). The main examples of strategies that were mentioned during the study involved intercropping, alternation of more resilient crops according to the weather patterns, increased use of technical farming tools, and the diversification of income sources.

The two tribes recognize the importance of forests in regulating local climate patterns and mitigating the impacts of climate change and their restoration efforts help to preserve biodiversity and maintain ecosystem resilience (Aydinalp, 2008). Efforts to address climate change and support indigenous communities should consider their unique needs, rights, and aspirations (Cardenas & Carpenter, 2013).

Towards sustainable agriculture practices

Considering that their traditional farming practices originally did not involve the use of chemical pesticides and insecticides, it is alarming that due to the increasing use thereof in surrounding areas the tribes are pressured to abandon the use of organic substances. These substances are not only often biodegradable, less persistent, and less harmful to the environment and humans (Narayanasamy, 2006), but also more easily available to the communities, which lessens the financial investment and dependence on external sources. The severity of the implications of commercial fertilizer use has become especially apparent during the recent price increase due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its restrictions on travel and shipping, as well as high fuel prices in the global market and the Russian-Ukrainian war (Tanduyan, 2022).