Submitted:

23 May 2023

Posted:

25 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

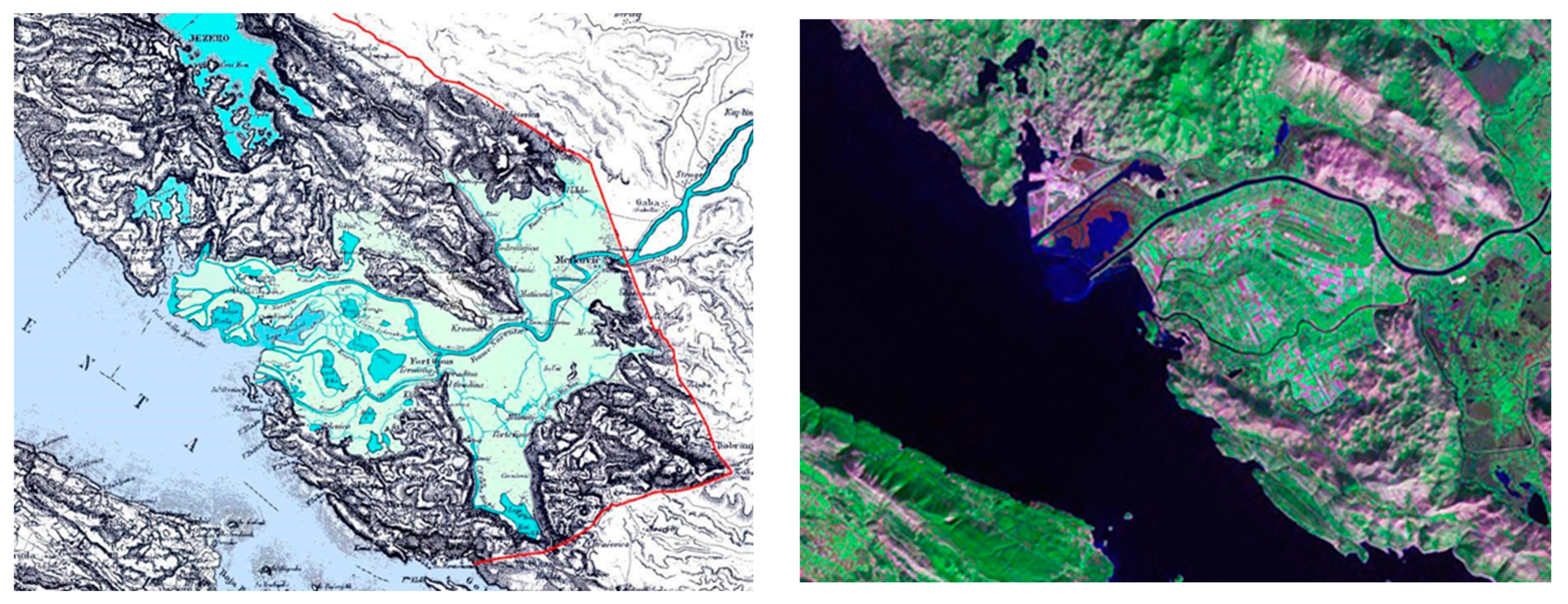

3.1. Natural eel Habitats Loss

3.2. Historical Captures

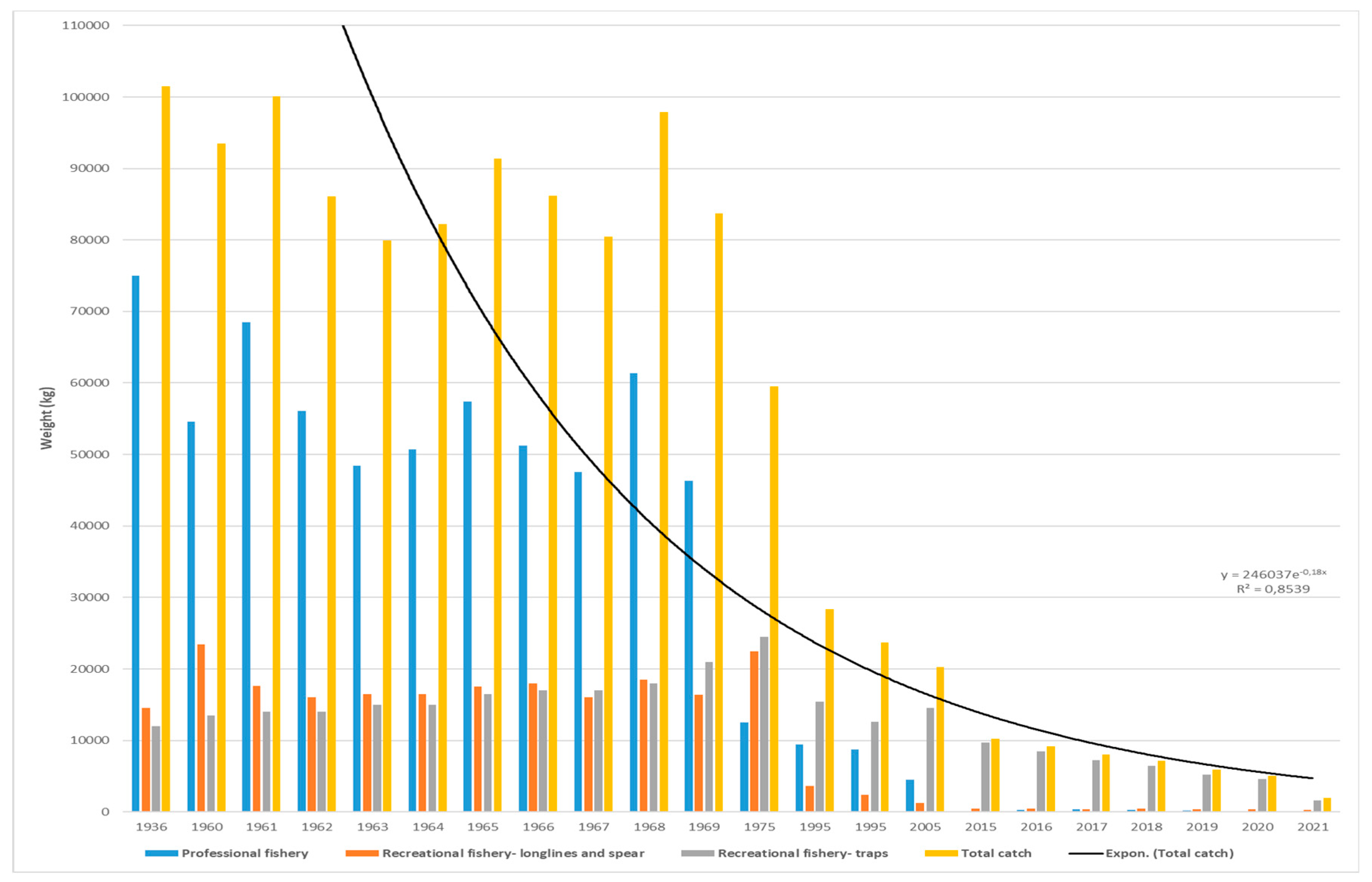

- The period from 1930-1940 was characterized by organized purchase of eel in the state station in town of Opuzen and its processing by drying or salting for sale in other markets. According to the available data, about 75 tons were purchased annually in the Neretva Delta. The annual sale of dried and salted eel was estimated at 20 tons, which corresponds to the amount of freshly caught eel (loss after cleaning and drying). In addition to the officially registered catches, recreational fishing with spears and longlines was also carried out during these years, but mostly for personal use, as resale was not possible. This period can be considered the pristine natural state of the eel population in the Neretva estuary, and the estimated catch of 100 tons of silver eel per year can be considered relatively reliable given the natural areas and their potential for eel growth.

- The period from 1960 to 1970 was characterized by large-scale reclamation of the main eel fishing areas below the town of Opuzen (Modrič lagoon and a number of salt lakes) and the town and port of Ploče (lagoons), and later also below the town of Metković, which was followed by a decline in catches in the 1970s. During this period, most of the catch was bought by state cooperatives, and a smaller part was used for personal needs through recreational fishing, as there was no tourism and restaurants.

- The period from 1970 to 1990 was characterised by a sharp decline in catches in commercial fisheries in the fall and winter, and interest in this type of hunting also declined. However, the increase in tourist activities and the beginning of restaurant and hotel operations (summer season) opened a new market for eel, so recreational fishing with pots, spears and longlines increased.

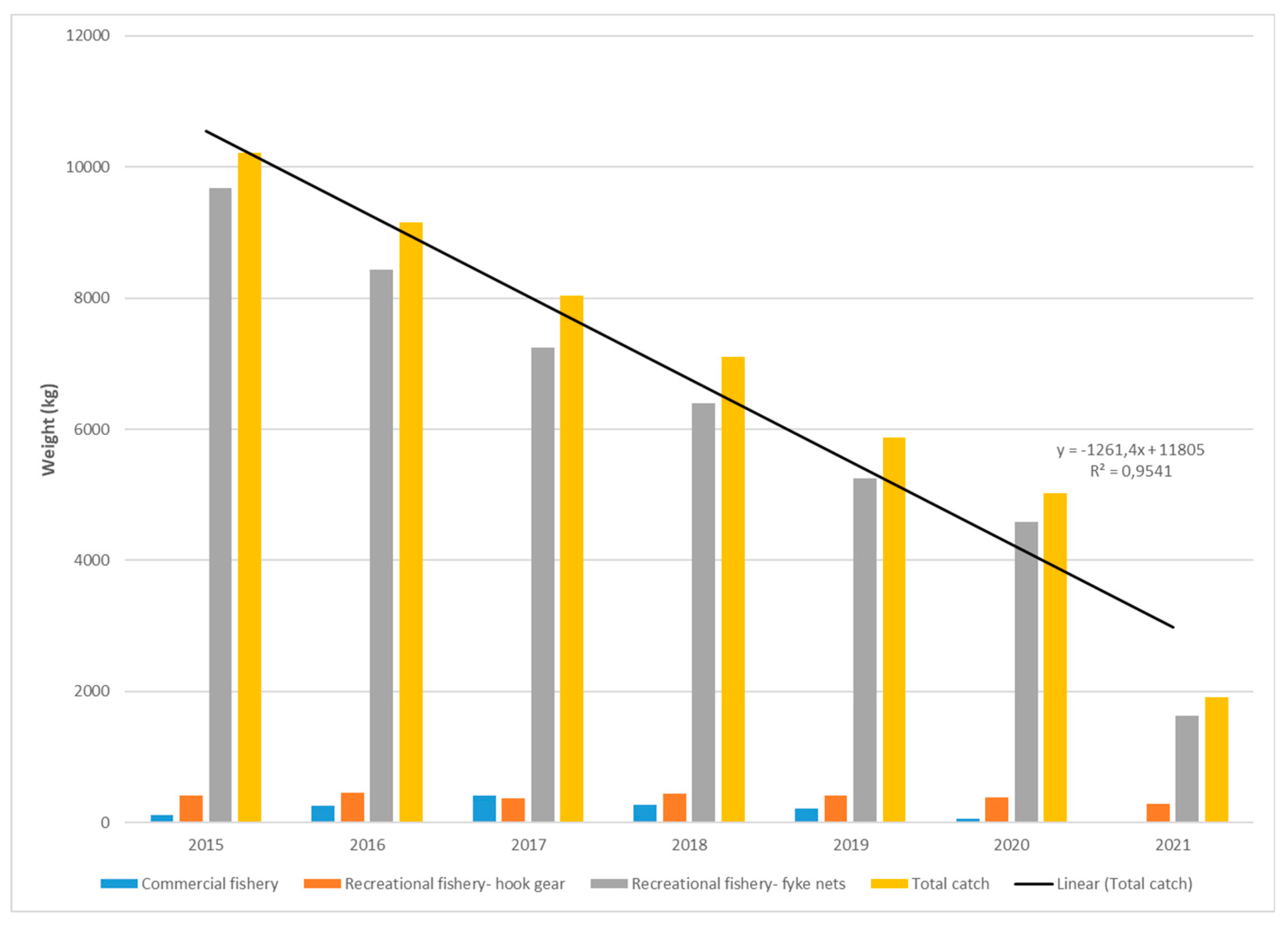

- The period from 1995 to 2013 was characterised by a further decrease in catches in commercial fisheries and the increase in the price of eel up to 20 €/kg, an increased interest in eel fishing with fish traps and small eel traps, as the number of these fishermen increased sharply due to the increasing number of new local retirees and the ban on eel hunting in Croatian protected areas (Lake Vransko). This is accompanied by an increasing demand for eel, uncontrolled catch of smaller and smaller eels and destruction of entire populations

- The period after 2013 and the official accession of Croatia to the EU follows a similar trend of decline in catches in commercial fisheries (autumn-winter) and even greater fishing effort (greater number of smaller, non-selective peaks), with similar effects as in the previous period. The price increase (now 30 €/kg) has also affected fishing in other areas of the Republic of Croatia, so recreational fishing has a significant negative impact on the eel stock. Due to increased controls by state institutions since 2020, the number of fishing gears used for recreational fishing (mainly small eel traps) has decreased significantly, but due to the high eel price, the fishing effort is still enormous, although eel catches are decreasing and the catch size is mostly 50-100 grams (Glamuzina et al., 2022). The number of eels under 30 grams has also declined significantly due to invasive species such as Largemouth bass in Kuti Lake [8] and blue crab in brackish water ecosystems [9] which either feed on or compete with eels.

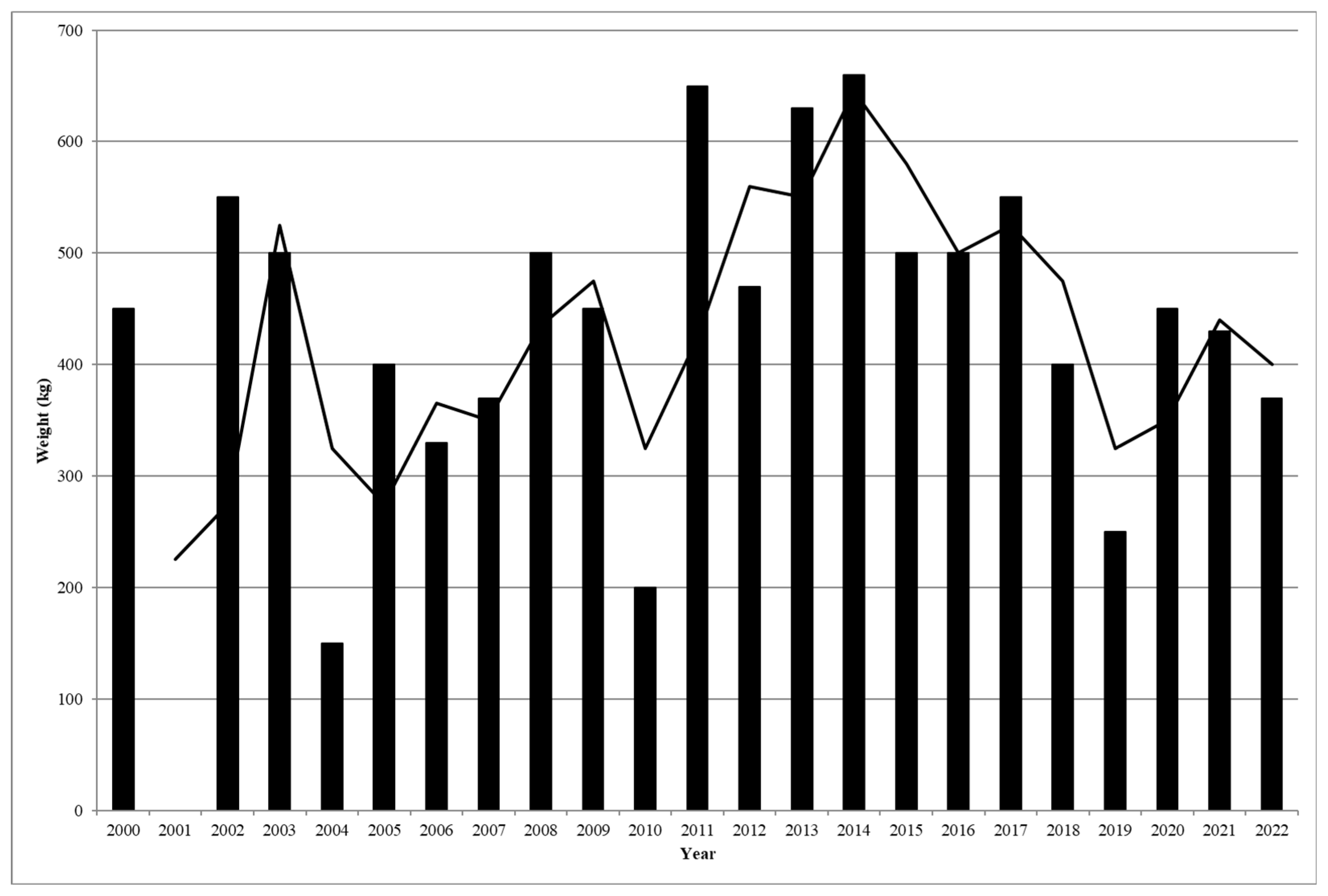

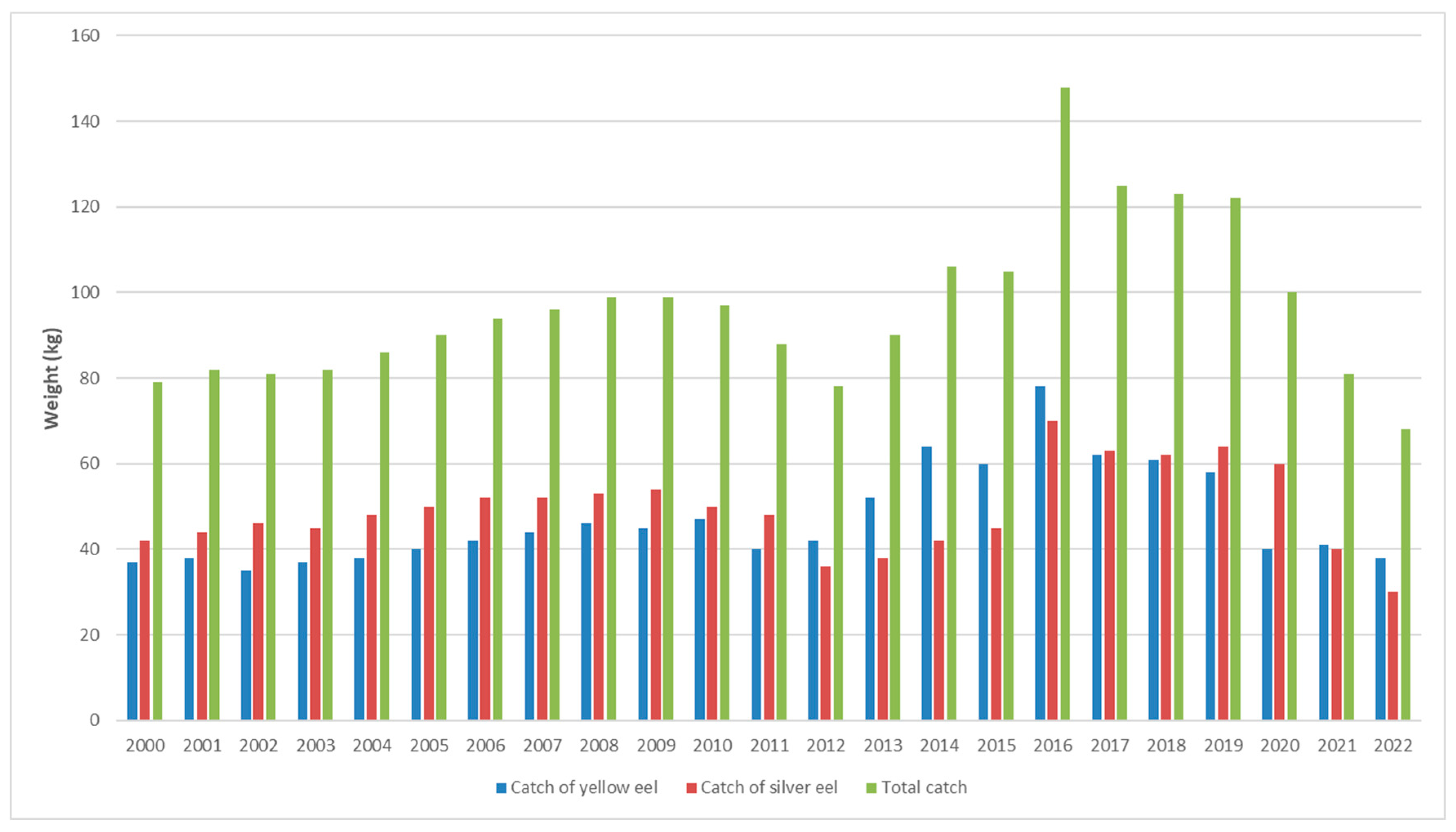

3.3. Eel Catches of the Commercial and Recreational Fishers in the Period 2000–2023 in the Neretva Estuary (Middle Eastern Adriatic, Croatia)

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aalto, E., Capoccioni, F., Terradez Mas, J., Schiavina, M., Leone, C., De Leo, G., & Ciccotti, E. (). Quantifying 60 years of declining European eel (Anguilla anguilla L., 1758) fishery yields in Mediterranean coastal lagoons. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2016, 73, 101-110. [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua D, Melia P, Crivelli AJ, Gatto M, De Leo GA. Multi-objective assessment 705 of conservation measures for the European eel (Anguilla anguilla): an application to 706 the Carmargue lagoons. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2007, 64, 1483-1490. [CrossRef]

- European Union (EU). 2007. Council Regulation (EC) No. 1100/2007 “Establishing 819 measures for the recovery of the stock of European eel”.

- Aprahamian MW, Evans DW, Briand C, Walker AM, McElarney Y, Allen M. The changing times of Europe's largest remaining commercially harvested population of eel Anguilla anguilla L. J Fish Biol. 2021 99, 1201-1221. [CrossRef]

- Glamuzina, L., Pećarević, M., Dobroslavić, T., Tomšić, S., Glamuzina, B. . The study of European eel, Anguilla anguilla in the River Neretva estuary (Eastern Adriatic Sea, Croatia) using traditional fishery gear. Acta Adriatica 2022, 63, 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Morović, D. 1948. Godišnje kretanje jegulje i cipla u Donjoj Neretvi. (Annual trend of eel and mullets in Lower River Neretva). Ribarstvo Jugoslavije, 9, 83-86. (In Croatian).

- Morović, D. Quelques observations sur l’anguille, Anguilla Anguilla L., de la côte ori-entale de l’Adriatique. Bilješke-Notes Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Split. 1970, 27, 1-4.

- Mrakovčić, ., Kresonja M., Glamuzina, B., Petravić, J., Trgovčić, K. 2021. Structure and characteristics of the fish community in the Neretva Delta after the introduction of the Largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides (Lacepède, 1802). 4 th CROATIAN SYMPOSIUM ON INVASIVE SPECIESwith International Participation / Jelaska, Sven D. (ur.). Zagreb: Croatian Ecological Society, 2021. str. 39-39.

- Glamuzina, L., A. Conides, G. Mancinelli, B. Glamuzina. . A Comparison of Traditional and Locally Novel Fishing Gear for the Exploitation of the Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab in the Eastern Adriatic Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021 9: 1019. [CrossRef]

- Erceg, J., 2003. Stanje hidromelioracijskih sustava na slivnom području Neretve- Donja Neretva, stručno-znanstveni skup- “Stanje i održivi razvoj hidromelioracijskih sustava u Hrvatskoj-Preduvjet razvoja poljoprivrede”, 28. i 29. listopada 2003., Zagreb.

- Petravić, J., Kresonja, M., Glamuzina, B., Mrakovčić, M. 2021.Dietary composition of the Largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides (Lacepède, 1802) in the lower course of the Neretva River in Croatia. 4th CROATIAN SYMPOSIUM ON INVASIVE SPECIES with International Participation / Jelaska, Sven D. (ur.). Zagreb: Croatian Ecological Society, 2021. str. 40-40.

- Guhl, B., Stürenberg, FJ. & Santora, G. 2014. Contaminant levels in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) in North Rhine-Westphalian rivers. Environ Sci Eur 26, 26. [CrossRef]

- Aschonitis, V., Castaldelli, G., Lanzoni, M., Rossi, R., Kennedy, C., and Fano, E. A. (2017) Long-term records (1781–2013) of European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) production in the Comacchio Lagoon (Italy): evaluation of local and global factors as causes of the population collapse. Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst., 27: 502– 520. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Dias, S., E. Dias, J. Lobon-Cervia, C. Antunes & J. Coimbra. 2010. Infec-tion by Anguillicoloides crassus in a riverine stock of European eel, Anguilla anguilla. Fish. Man. Ecol.,17, 6: 485-492. [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D., A.H. Arthington, M.O. Gessner, Z. Kawabata, D.J. Knowler, C. Leveque, R.J. Naiman, A-H. Prieur-Richard, D. Soto, M.L.J. Stiassny & C.A. Sullivan. 2006. Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation chal-lenges. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc., 81(2):163-82. [CrossRef]

- De Leo G.A. and Gatto M., 1995. A size and age-structured model of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 52, 1351–1367. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R. 1979. An estimate of the production of the eel population in the Valli of Comacchio (Po Delta) during 1974–1976. Italian Journal of Zoology, 46:3, 217-223. [CrossRef]

- Amilhat, E., H. Farrugio, R. Lecomte-Finiger, G. Simon and P. Sasal. 2008. Silver eel population size and escapement in a Mediterranean lagoon: Bages-Sigean, France. Knowl. Managt. Aquatic Ecosyst., 390-391. [CrossRef]

- Feunteun E., Acou A., Laffaille P. and Legault A., 2000. European eel (Anguilla anguilla): prediction of spawner escapement from continental population parameters. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 57, 1627–1635. [CrossRef]

- Acou A., Gabriel G., Laffaille P. and Feunteun E., 2009. Differential production and condition indices of premigrant eels in two small Atlantic coastal catchments of France. In: Casselman J.M. and Cairns D.K. (eds.), Eels at the edge: science, status, and conservation concerns, Amer. Fish. Soc. Symp., 58, Bethesda, Maryland, 157–174.

- Panfili, J., M.-C. Ximénès, and A. J. Crivelli. 2011. Sources of Variation in Growth of the European Eel (Anguilla anguilla) Estimated from Otoliths. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 51(3): 506-515. [CrossRef]

- Vollestad, L. A., & Jonsson, B. (1988). A 13-Year Study of the Population Dynamics and Growth of the European Eel Anguilla anguilla in a Norwegian River: Evidence for Density-Dependent Mortality, and Development of a Model for Predicting Yield. Journal of Animal Ecology, 57(3), 983–997. [CrossRef]

- Glamuzina, B., V. Bartulović, A. Conides, N. Zovko. 2008. Status populacije europske jegulje, Anguilla anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758) na području močvare Hutovo blato, Bosna i Hercegovina (Status of European eel population, Anguilla Anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758) in the wetlands of Hutovo blato (Bosnia and Herzegovina)). Proceedings. 43rd Croatian and 3rd International Symposium on Agriculture / Pospišil, Milan (ur.). Zagreb: Agronomski fakultet, 2008. 733-736.

- . [CrossRef]

- Bukvić, V., Dušak, V., Kučinić, M., Delić, A., Dulčić, J., Senta, I. and Glamuzina, B. (2011), Arsenic in the water, sediment and fish in the Neretva River Delta, Croatia. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 27: 908-911. [CrossRef]

- Bark, A., Williams, B., and Knights, B. 2007. Current status and temporal trends in stocks of European eel in England and Wales. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 64 (7), 1368–1378, . [CrossRef]

- García Manteca, P., Nores Quesada, C., Cuervo, N., Colubi, A., y García Flórez, L. (2015). Estimación del área húmeda, actual y potencial, disponible para la anguila europea (Anguilla anguilla) usando técnicas GIS. GeoFocus (Artículos), 16, p.41-60. ISSN: 1578-5157.

- Nzau Matondo, B.; Backory, L.; Dupuy, G.; Amoussou, G.; Oumarou, A.A.; Gelder, J.; Renardy, S.; Benitez, J.-P.; Dierckx, A.; Dumonceau, F.; et al. 2023. Space and Time Use of European Eel Restocked in Upland Continental Freshwaters, a Long-Term Telemetry Study. Fishes, 8, 137. [CrossRef]

| Reclamation areas: habitat types | Total reclaimed area (hectare)* | Potential eel biomass (kg/ha)** | Estimated total lost eel biomass (kg-h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower estuary (brackish 15-30 psu)) | |||

| Mediterranean lagoons (Town of Ploče area) | 1 661 | 20 | 33200 |

| Mediterranean lagoons (area bellow town of Opuzen) | 2 600 | 20 | 52000 |

| Middle estuary (brackish 10-20 psu) | |||

| Mediterranean lagoons- middle estuary (Kuti area) | 274 | 15 | 4100 |

| Upper estuary (0.3-5 psu) | |||

| Freshwater bodies | 616 | 10 | 6100 |

| Freshwater estuarine bodies | 1 867 | 10 | 18000 |

| Freshwater estuarine bodies- lakes, rivers and channels | 1 972 | 10 | 19000 |

| Other areas | |||

| Other smaller wetland areas (not divided to specific habitat type) | 2 500 | 15 | 25000 |

| Total | 11 490 | 157400 |

| Period | Average silver eel yearly capture(tons)* | Average yellow eel yearly capture (tons)** |

|---|---|---|

| 1930-1940 | 75 | 45 |

| 1960-1970 | 45 | 30 |

| 1980-1990 | 25** | 30 |

| 2010-2020 | 2 | 3 |

| 2022 | 1 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).