1. Introduction

European Protected Areas (PAs) create a unique mosaic of rich, diverse, intricate landscapes that encompass a wide variety of natural and semi-natural environments. Europe has the most extensive network of protected areas in the world, dedicated to achieving the long-term conservation of nature. Europe’s PAs are managed through legal regimes or other means that vary greatly and are characterized by several different designation types applied at local, national, regional, and international level [

1].

The management regimes of PAs attempt to address various pressures on European biodiversity and among them the alarming decline of farmland biodiversity. Historically, traditional low-intensity agriculture in Europe contributed significantly to increasing the diversity of landscapes and species [

2,

3,

4]. Most of the low intensity farming systems have been developed over time, with farm structures and traditional farming practices being closely adapted to the local environmental, social, and economic conditions [

2,

5]. However, in the context of modern agriculture that has radically transformed the agricultural sector over the last decades, the traditional low-intensity farming systems have become unprofitable leading to either abandonment or intensification of farming practices. This pattern of agricultural production resulted consequently to a substantial decline of habitats associated with agriculture (semi-natural habitats) and farmland-related species, and additionally to the loss of valuable cultural knowledge [

6].

Today, the crucial role of low-intensity farming practices in maintaining farmland biodiversity is broadly recognized. Yet, low-intensity farming systems tend to generate low incomes, are often labour intensive [

2] and due to social and economic pressures are usually difficult to survive especially in the absence of financial support [

6]. Therefore, in many European PAs, the protection and continuation of these systems is part of their biodiversity protection strategies and management plans, supported through EU and/or national financial resources and programming tools [

7].

One of these tools is the development of certification and labelling schemes [

6] that can be used to promote environmentally friendly practices and high-quality products developed within the territory of the protected area and reinforce its local image and identity [

8]. The “labelling” tool is usually applied as a complementary tool based on wider conservation projects [

9]. With specific reference to farming, food products produced under specific methods that benefit biodiversity and support the management of farmland habitats and species can use the name and brand logo of a PA [

6,

10]. The labelling of local food products can raise environmental awareness among the farmers who can act as “guardians/stewards of nature” [

11] with the aim to safeguard the unique biodiversity and natural resources of PAs. On the other hand, it can offer socio-economic benefits to local farms and food companies by providing a marketing edge over their competitors and/or an improved market position through product differentiation [

12]. These schemes are mainly local labelling schemes which can support the development of niche markets and provide ecological accreditation for these products [

13].

From a consumer perspective, a quality label provides information on the specific characteristics and unique qualities of the product such as a certain geographical origin, traditional production methods, environmentally friendly practices etc. [

14]. Thus, labelling food products with the brand logo of a PA could raise public awareness towards ecological issues by linking the brand logo of a PA with biodiversity conservation, enhancement of local resources and traditional farming practices [

8].

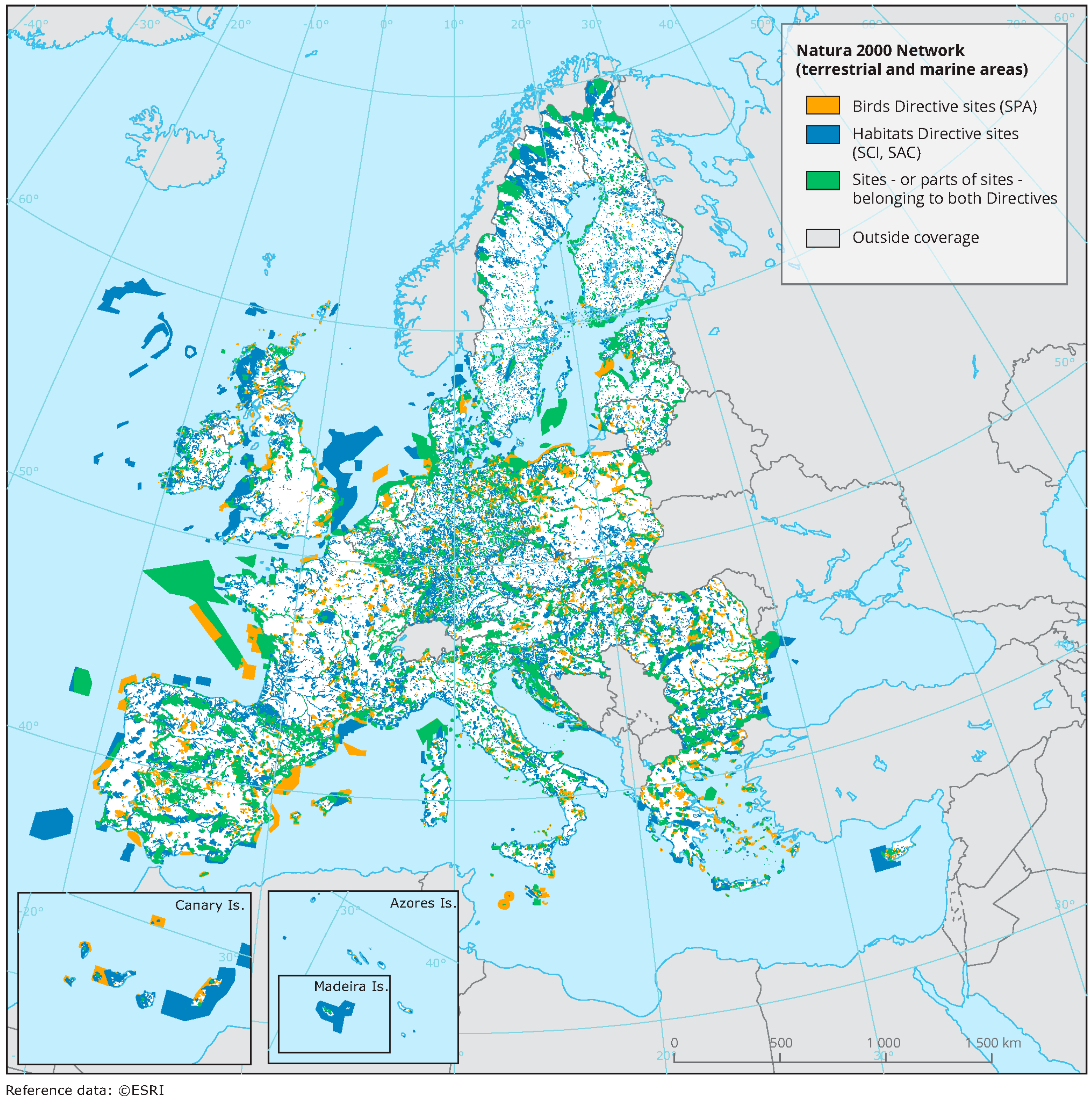

In this context, the environmental and socio-economic issues associated with farming practices, production methods and labelling schemes for agri-food products of the European PAs are of great interest. Especially if we consider that PAs today cover a relatively large part of Europe and farming is an important part of the local economies of these areas. Overall, PAs cover more than 25% of the EU terrestrial land territory and the European ecological network Natura 2000 (

Figure 1), the largest coordinated network of protected areas in the world, accounts for 18% of the EU’s land territory and more than 8% of its marine territory [

1]. Farmland makes up around 40% of the total area included in Natura 2000 sites supporting many farmers and local communities [

6].

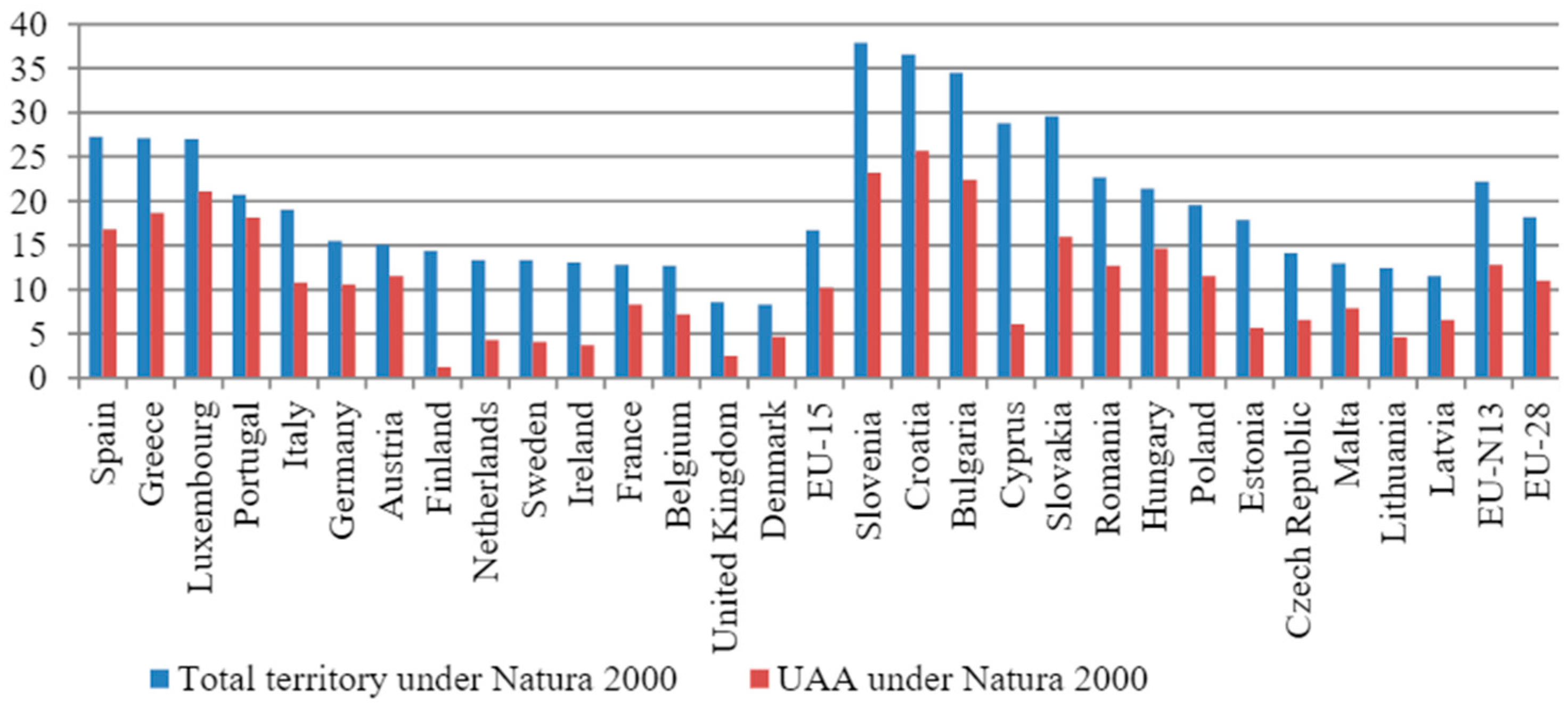

Figure 2 outlines the total area of the Natura 2000 Network of the European Union countries and the agricultural land area covered by this form of protection. Characteristic is the example of Italy where more than 230.000 farms operate within the administrative boundaries of the National Parks and farmland inside the Italian PAs occupy about 9% of the total national farmland [

11].

Figure 1.

Natura 2000 Network (terrestrial and marine areas) for EU28 countries in 2018 (Source: [

15]).

Figure 1.

Natura 2000 Network (terrestrial and marine areas) for EU28 countries in 2018 (Source: [

15]).

Figure 2.

Proportion of total territory under the Natura 2000 Network and utilized agricultural area (UUA) including natural grassland in 2016 (Source: [

16]).

Figure 2.

Proportion of total territory under the Natura 2000 Network and utilized agricultural area (UUA) including natural grassland in 2016 (Source: [

16]).

It is therefore surprising, as also noted by other researchers [

8,

10,

17] that academic research on this issue is scarce. There might however be different valid reasons for the limited research on this topic. Regarding farmland biodiversity and the role of low-intensity farming systems it seems that most researchers have directed their interest towards the concept of High Nature Value (HNV) farmland [see e.g., 5,18,19]. HNV areas typically represent the remaining traditional agro-ecosystems of Europe and while they are not equivalent to PAs, there is a considerable overlap [

18,

20]. Respectively, a significant number of studies has focused on the EU food quality labelling schemes: Protected Designation of Origin - PDO, Protected Geographical Indication - PGI and Traditional Speciality Guaranteed - TSG. While these labels provide no guarantee that the products benefit in any way farmland biodiversity, there are many examples of products registered under these EU quality labels that are produced inside protected areas [

6].

Under this spectrum, this paper review is an attempt to gather and analyse in depth the findings of the existing studies focusing on the relationship between the European PAs, farming systems and certification/labelling schemes of agri-food products with a PA logo. It is the aim of the present paper to give an overview of what is known on this topic and serve as a starting point for discussions and reveal opportunities for further research in the future. To achieve this goal, our study is guided by the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Which dimensions of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic) have been studied within the literature of farming systems that are identified inside the European PAs?

RQ2: How certification/labelling schemes of agri-food products with a PA logo influence sustainable regional development?

RQ3: What methodological approaches or theories have been employed within the literature identified?

The following section presents the Materials and Methods, followed by the Conceptual framework in

Section 3, the Results in

Section 4 and the Discussion in

Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2. Materials and Methods

An in-depth review and analysis of the scientific and grey literature has been conducted with the purpose to identify and appraise information to address the research questions posed in the previous section. Our basic aim was to identify papers focusing on the environmental and socio-economic issues associated with farming practices, production methods, and labelling schemes for agri-food products of the European PAs. Due to the unique features of the semi-natural habitats and cultural aspects that characterise the European PAs’ landscapes, we decided to include only studies that were carried out inside PAs within a European-wide context. Following this, the identification of publications with explicit reference on labelling/certification schemes for agri-food products with the brand logo and name of a PA, was set as our key priority. Complementary, we searched for publications that analyse the sustainability dimensions of farming systems identified inside the European PAs and their correlation with the production of high-quality products.

To gather the available relevant studies and research, we performed a literature search using large academic databases that included Scopus-Elsevier, Google Scholar, and Web of Knowledge. To keep the search as broad as possible, we established three main sets of keywords and used multiple combinations of these keywords in our search. The first set of keywords referred to the geographic area of our interest and the type of Protected Area. We included here the words “Europe”, “Protected Areas”, “National Parks”, “Biosphere Reserves”, “Natura 2000 areas”. The second set of keywords contained words related to labelling schemes. We included here the words “labelled products”, “certification”, “label”, “brand”, “logo” and we also added words that specify the development of quality schemes including: “food quality”, “local food”, “alternative food networks”, “sustainable development”. In the third set of keywords, we included words that are relevant to farming systems and agricultural practices: “agriculture”, “farming”, “farming systems”, “traditional landscapes”, “low-intensity”, “abandonment”, “intensification” and “farmland biodiversity”.

In addition, studies commissioned by authorities were identified through EU websites. Cross-referencing led to the identification of papers that were included in the present study and served as a useful tool to make sure that relevant studies were not overlooked. To ensure the accessibility of the literature, only studies published in English were considered. Our search resulted to the selection of 21 publications for in-depth examination. After a thorough analysis, we removed 7 publications either because of the absence of a PA certification label for agri-food products or because the chosen study area was not specifically referring to a designated PA. In addition, 4 publications were excluded because the focus of the study was on specific agricultural management measures without depicting the multifunctional role of agriculture and the production of high quality agri-food products. The final set of papers included in the present review consist of 10 publications. Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis was not seen as necessary due to the relatively small sample size.

4. Results

In the following, we synthesize the findings of the reviewed papers, guided from our research questions and conceptual framework. First, we present some general information and results derived from the analysis of all the reviewed papers. Then, we distinguish the review papers into two categories. In the first category we grouped the publications that have studied the multifunctional role of farming systems inside the European PAs. They analyse the relationship between the protected areas, agriculture, and local dynamics, focusing on the implications of farming systems and high-quality local products to sustainable regional development. In the second category, we distinguished the publications with specific reference on PAs that use their brand logo and name on the labels of agri-food products as a means of achieving socio-economic development goals alongside with conservation objectives. In our review, we comment on the methodologies and theories employed by the researchers.

4.1. General results

We based our review on ten papers which makes clear that academic research on the subject is scarce. Most of the research has been conducted during the last decade and most papers have been published from 2017 onwards.

All publications underline the important role of PAs in safeguarding our remaining most valuable natural, agricultural, cultural, and social heritage. Rural communities coexist with the natural environments of PAs and thus economic and social goals should be achieved alongside with the primary goal of environmental conservation. In this context, PAs can function as real-world laboratories of sustainable rural development, promoting social regeneration and a more environmentally healthy and economically viable model for society.

Most publications indicate the environmental benefits of traditional low-intensity farming systems and the complex interrelationship between agricultural practices and biodiversity. Traditional farming systems are today economically unprofitable, and thus their maintenance and continuation require more innovative approaches, participatory work, and financial support. The ecological value of these systems and the multifunctional role of agriculture in PAs has been neglected, along with the role of farmers as the direct managers of the land.

Almost all papers mention the impressive growth of local, regional brands and quality schemes introduced in the European market, over the last years, as an important strategy to foster regional development. Labels that signal the product’s origin, quality, method of cultivation, etc. influence consumers’ decisions that seek products with unique characteristics. Thus, the differentiation of agricultural products of PAs, through labelling and information, can be a proactive market-based instrument to support the local economy, promote environmentally sound practices, raise environmental awareness, and preserve biodiversity in PAs.

4.2. Results on farming systems inside the PAs

We identified five papers (

Table 1) that focus on the sustainability dimensions of farming systems inside the European PAs. Three publications focus on traditional low-intensity farming systems. One publication explores the impacts of organic farming as an alternative strategy for farmers and one the trends in agricultural production inside the PAs over the last two decades. Due to the small number of publications, we organise the results of our analysis in chronological order by the publication date.

The first paper we identified was published in 2008 by Jansen [

29]. The area studied was a Natural Park in Portugal that incorporates a large Natura 2000 area. Based on long-term observations and experiences in the study area, the author attempts to qualify the benefits of traditional farming systems for both biodiversity management and rural development. The study area was chosen as one of the last living examples in Western Europe that continue to support traditional agro-pastoral systems. The traditional knowledge and methods that farmers and shepherds apply enables them to conserve the rich biodiversity of semi-natural biotopes while sustaining their cultural heritage. The paper in its methodological approach uses the study area as a reference area to other countries that attempt, sometimes through high-cost projects, to restore the quality of the cultural, natural, and environmental aspects of agricultural landscapes in designated areas.

Hadjigeorgiou and Zervas [

30] evaluated the pastoral livestock farming systems in two different areas in Greece which are protected under the Natura 2000 network. The researchers conducted a survey with farmers, using structured questionnaires, to analyse different socio-economic aspects of the livestock systems at the farm scale. The farms identified in the study area were mainly small size sheep and goat farms, generally characterised as being extensive. In addition, a vegetation sampling provided information regarding the role of grazing livestock in the management and conservation of pastures. The main trends and findings identified in the study areas can be summarised as follows: transition of extensive livestock farms to more intensified management systems; gradual degradation of grazing resources; concentration of grazing in water rich and easy to access areas; high cost of labour, harsh working conditions and low social status endanger the continuity of the farms’ operation; small size farms with aged and low education farmers deter the adoption of technical advantages.

A study published in 2020 by Morales-Jerrett et al. [

31] is the first assessment research aiming to analyse the sustainability of traditional meat goat farming and its contribution to human wellbeing. Through a technical-economic and environmental study of some farms with autochthonous goat breeds in selected Andalusian PAs in Spain, the economic viability of the sector, ecosystem services, limiting factors and proposals for the profitability and continuity of the sector were explored. Pastoral goat farming systems generate low income and the lack of acknowledgement and remuneration of the ecosystem services they provide is leading to a progressive decline of grazing livestock systems.

The opinions of organic and conventional farm owners on the economic satisfaction of running a farm inside a PA has been studied in a Natura 2000 area in Poland by Pawlewicz et al. [

32]. Organic farming inside the PAs can be an alternative maintenance strategy to conventional farming as it can sustain the development of rural areas and mitigate the effects of restrictions imposed by the PA. An empirical study with a sample of 152 organic farm and 140 conventional farm operators indicated that there is no major difference between the opinions expressed by organic and conventional farm owners. Conventional farmers were slightly more satisfied mainly because of the easier access on sale markets for their products. Due to the flexible form of protection in Natura 2000 sites, most farmers felt no impact of legal restrictions on their business activities.

The last study chosen in this category was published in 2022 by Cejudo-García et al. [

33]. The purpose of the research was to assess the effectiveness of PAs as drivers of sustainable development for these and the surrounding areas. Using the trends in agricultural and livestock farming as an indicator of rural/local development dynamics the authors compared the evolution of farming specialisation in two PAs, one in Spain and the other in Italy, over a 20-year period. The analysis of the changes and shifts in farming reveal the political decisions, local participation in decision making and the influence of market forces. Extensification of farming, abandonment of farmland, specialisation of crops, introduction of capital-intensive greenhouse forms of agriculture, loss of traditional crops and agricultural landscapes have a significant impact on the sustainability of these rural areas. The results of the study indicated that the conservation of the natural heritage was the priority of PAs. On the other hand, there was a lack of adequate measures and actions that could promote the multifunctional role of agriculture and enhance the agricultural heritage and farmland biodiversity of these areas.

Table 1.

Sustainability dimensions of farming systems inside the PAs.

Table 1.

Sustainability dimensions of farming systems inside the PAs.

| |

Dimensions of Sustainability |

| Reference |

Farming

system

|

Aim of study |

Products |

Social |

Economic |

Environmental |

| Jansen, 2008 |

Traditional agro-pastoral farming system |

Qualification of the benefits of traditional farming systems for biodiversity management and rural development |

Agri-food products |

- Traditional

farming knowledge |

- High quality food products |

- Semi-natural habitats’

biodiversity |

| Hadjigeorgiou & Zervas, 2009 |

Pastoral livestock farming system |

Evaluation of the pastoral livestock systems at the farm scale and the role of grazing livestock in the management and conservation of pasture resources |

Sheep and goat

products |

- Harsh working conditions

- Absence of

successors

- Social

devaluation

- Age & education |

- Farmer’s

income

- High cost

of labour |

- Conservation of pasture

resources |

| Morales-Jerrett et al., 2020 |

Traditional

meat goat

farming system |

Contribution of traditional meat goat farming to human wellbeing and the sustainability of the sector |

Goat meat |

- Human

wellbeing |

- Farmer’s

income

- High quality food products |

- Carbon

footprint

- Forest wildfire prevention

- Autochthonous goat breeds |

Pawlewicz

et al., 2022 |

Organic

farming |

Farmers’ opinion towards organic farming as an alternative maintenance strategy in Natura 2000 areas |

Agri-food products |

_ |

- Economic satisfaction of farmers |

_ |

| Cejudo-Garcίa et al., 2022 |

Farming

systems |

Effectiveness of PAs as drivers of sustainable development |

Agri-food products |

- Local community participation |

- High quality food products |

- Farmland biodiversity

- Agricultural landscapes |

4.3. Results on labelled agri-food products of PAs

In our research we found only 5 academic papers (

Table 2) that aimed to analyse the environmental and socio-economic impacts of the certification/labelling schemes of agri-food products with a PA logo. Despite the quite small number of studies on the topic, these articles enable us to extract important information on the effects and potentials of labelled products for the sustainable development of the PAs.

Already in 2001, Knickel [

34] in his paper, focused on the case study of the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Rhön in Germany and the development of a new product line of organic dairy products to examine the multifaceted character of rural development processes and illustrate the important link between agricultural activities and the natural resources, cultural landscapes, and socio-economic development of rural areas. The Biosphere Reserve Rhön is a typical example of a moderately mountainous area with meadows and pastures where traditional farming systems are linked with high nature values. An area with natural constraints that followed the same trend as other mountainous areas in Europe during the first decades of the second half of the 20

th century. Most farmers abandoned the traditional forms of agriculture and young people left the area leading to a general socio-economic deterioration. The Rhöngold dairy and organic farming case study is a successful example of rural development process that influenced among other factors the regeneration of the region and led to the re-evaluation of regional conditions. Rhöngold products embrace the ecological values and management principles of the Biosphere Reserve and use its positive ‘green/intact nature’ image and label for their advertisement. In this regard, nature and landscape conservation, environmentally friendly farming methods, high-quality products, green tourism, and quality of living conditions are all interconnected. The researcher uses this case to examine the theoretical implications of the multifunctional role of agriculture at farm and regional level, which more than any other activity has the capacity to play an integrating role in sustainable rural development (a more analytical framework on the structure of multifunctionality in the Rhöngold case is presented in the paper of Knickel and Renting [

21].

Two of the studies we reviewed have focused their research on the economic impact of labelled local products that use the brand logo of a PA and their ability to foster sustainable economic development. The first study, published in 2014 by Kraus et al. [

35], is to our knowledge the first academic attempt to analyse the impact of a local labelling scheme of a PA on regional economies. The two studies complement one other, and both have used as case studies well-managed Biosphere Reserves, the one in Germany (Rhön Biosphere Reserve) and the other in Switzerland (Entlebuch Biosphere Reserve). The second study published in 2017 by Knaus et al. [

17] with the purpose of providing more information on the monetary effects of all labelled products that use the brand logo of a PA and their potential to stimulate the regional economy.

Both papers recognise the general lack of quantitative data to measure the impacts of PAs’ regional products and its contribution to regional economic development. They acknowledge, however, the practical difficulties and the significant effort needed to gather the adequate data for a comprehensive analysis. In their methodological approach the researchers used a two-group comparison research to compare the results and estimate the impact of the labelled products in relation to the regional products outside the PA. The first study focused on the analysis of local supply chains in the economic sectors of tourism and food processing and the results were based mainly on important economic data gathered through interviews. The second study calculated the regional added value for agriculture and forestry related products using statistical data from the national and cantonal levels, interviews and other studies and databases.

The key outcome of these two studies is that a label can be a significant asset for PAs and their management. In the case of the Rhön Biosphere Reserve in Germany, the label helped strengthen selected local added-value chains. Similarly, the labelled products of the Entlebuch Biosphere Reserve contributed significantly to the regional economy. Moreover, both studies presented some important concluding remarks. Τhe labelling schemes that promote the products of these PAs were based on a bottom-up concept and thus there was a need for a continual process to establish synergies and good and trustful cooperation between the involved stakeholders within the regions. Additionally, the labels should be able to depict the quality specifications of the products, their identity and origin, and raise consumer awareness.

The other two studies come from Italy, and both focus on consumer perceptions towards food products that are produced by firms located within the Italian National Parks and use the parks’ brand (name and logo). The first paper, published in 2017 by Temperini et al. [

10], is the first empirical research to investigate the impact of national park brands of food products on consumers’ attitudes and behaviours. The researchers conducted a survey with face-to-face interviews, involving a sample of 227 Italian consumers, to gather data on the factors that influence consumers’ trust in food quality and their willingness to pay premium prices for the national park brands. The results of the study indicated that women seem to be more sensitive towards environmental issues and pay more attention to food naturalness and the use of chemicals in agricultural production. Along the same lines, younger people have a more positive attitude towards organic food and certified products. Therefore, these two categories of consumers showed a greater degree of confidence towards the quality of food products with the label of national parks and willingness to pay more for food products that preserve natural resources.

Three years later, in 2020, another research study followed on the same topic by Ferrari [

8], considering consumers’ growing demand for eco-friendly products, that has been observed during the last years. Labels of origin and territorial brands that are strongly related to a place are important information and marketing tools. Therefore, the author assumes that as PAs are symbols of naturalness, wilderness, ecological integrity, biodiversity, and quality goods, thus the food products with the labels of National Parks could generate positive effects for local products, services and/or resources. To test this hypothesis the author used literature data and conducted meetings with experts in this field to gain information on the branding strategies and related regulations of the Italian National Parks. In addition, a qualitative survey was performed, based on 35 in-depth interviews, to analyse the perceptions of consumers towards National Parks as touristic destinations and towards products with the brand logo of the National Parks. The results of the study show that protected areas can promote sustainable objectives and raise public awareness towards environmental issues with the use of effective branding policies that reinforce their local image and identity. This is quite relevant to agri-food products that are directly linked to health and environmental concerns, production techniques, and local traditions and culture.

Table 2.

Sustainability impacts of agri-food products with a PA label.

Table 2.

Sustainability impacts of agri-food products with a PA label.

| |

Sustainability impacts |

| Reference |

Label |

Aim of study |

Products |

Social |

Economic |

Environmental |

| Knickel 2001 |

Dachmarke Rhön |

Socio-economic and environmental effects of high-quality dairy products with the Biosphere

Reserve Rhön label |

Organic dairy

products |

- Quality living conditions

- Positive green regional image

- Food quality

- Synergies &

cooperation |

- Value-added quality products

- Improved

farmers’ income

- Local

employment

- Green tourism

|

- Sustainable production & use of natural resources

- Traditional high

nature value farming systems

-Diversification of production

- Nature & landscape conservation |

| Kraus et al., 2014 |

Dachmarke Rhön |

The contribution of the regional labelling scheme Dachmarke Rhön to sustainable economic development |

Tourism & traditional agri-food products/

services |

- Synergies &

cooperation

- High quality standards |

- Local buying in enterprises

- Local added-value chains

-Sustainable short supply chains |

_ |

| Knaus et al., 2017 |

Echt Entlebuch |

The economic impact of labelled regional products of the Entlebuch Biosphere Reserve |

Agri-food & forestry products/

services |

_ |

- Regional

added value

- Local

employment |

_ |

| Temperini et al., 2017 |

Italian

National Parks’ brands |

Consumers’ trust in food quality and their willingness to pay premium prices for the National Park brands. |

Agri-food products |

- Food quality

certifications & branding

- Origin, image, identity

- Environmental consciousness

- Consumer green/ethical

behaviour |

_ |

_

|

| Ferrari 2020 |

Italian

National Parks’ brands |

The role of National Parks’ branding strategies to generate positive effects for local products, services and/or

resources. |

Agri-food products/

services |

- Origin, image, identity, culture

- Environmental consciousness

- Brand equity |

_ |

_ |

4. Discussion

The first finding that emerges from the results of the literature review is the limited research towards the multifunctional role of agriculture in the sustainable development of the European PAs. Integrated approaches that focus on addressing the impacts of farming systems on the natural environment and local socio-economic developments of PAs have not been given much attention. Moreover, the role of certification/labelling schemes of PAs’ agri-food products that use the brand logo of the PA in the effective management of PAs and the achievement of environmental and socio-economic development goals have not been thoroughly addressed. It seems that the direct link of PAs’ high quality agri-food products with the conservation of farmland biodiversity and preservation of cultural landscapes and heritage through branding is not such a common approach in Europe.

Existing research on the European PAs has been mainly focused on issues that are easier to assess like the economic impact created by tourism [

36,

37] or the implementation of individual improvement agri-environmental measures [

38,

39]. However, understanding the actual role of farming systems in the management and conservation of PAs requires a multidisciplinary approach [

30] and a lot of effort to gather the necessary data and conduct a comprehensive study [

17,

35]. This is because farming is a rural activity with a highly integrative role in rural development as it produces a range of goods and services, links various fields and involves multiple actors among different levels [

21].

The reviewed literature, despite limited, showed a wide range of sustainability dimensions related to farming systems, indicating the complex and multifunctional role of agricultural production in the sustainable rural development of PAs.

Farmers’ subjective feelings are of high importance as they are the ones who carry out agricultural production and take decisions on the management of the land. Their decisions can result in the maintenance of sustainable agricultural practices of high natural quality or to the abandonment and even intensification of their production. The choices of farmers are based on incentives which are mainly influenced from a combination of social and economic parameters. Social factors, like the harsh working conditions and low social status associated with agriculture can be a significant reason for the abandonment of farming activities especially in the mountainous PAs with natural constraints [

30]. Additionally, the establishment of PAs imposes restrictions in land use activities which can influence farmers’ income as they might limit their ability in profit maximisation [

32]. While in some PAs the legal form of protection appears to be quite flexible [

32], in other cases, environmental restrictions on agricultural production have resulted in the abandonment of previous farming systems like the traditional agro-pastoral systems [

31]. Subsidies for organic farming and participation in agri-environmental schemes (AES) can provide a good economic incentive for farmers [

32] which can also be combined with other complementary activities like processing and direct marketing of their high-quality products or other agritourism activities [

34]. On the other hand, livestock intensification and cultivation of more specialised profitable crops in the most fertile and easily accessible areas is a common practice in recent years [

30,

33]. Of high interest and probably a trend of the last decade has been identified mainly in the Mediterranean countries. Influenced by the impacts of climate change, especially high temperatures, intense rainfalls and hail, the installation of greenhouses either to protect crops and/or increase production has gained significant ground. In the case of the Sierra Nevada Natural Park in Spain, greenhouses above 900m of altitude are prohibited and punished with a fine from the regional authorities, with the aim to protect biodiversity and the traditional landscapes of the park. However, during the summer months, the cooler temperatures in the mountains favour the production of vegetables and produce high level of income and employment. Therefore, capital-intensive greenhouse systems for vegetables inside the park have become popular among local farmers and companies, creating conflicts between conservation and economic interests [

33].

One of the most conspicuous aspects identified by our review is the need to acknowledge the value of low-intensity farming systems and traditional agricultural landscapes not only for their environmental, but also for their socio-cultural services. Morales-Jerrett et al. [

31] indicated the connection of traditional meat goat farming systems with human wellbeing. These pastoral systems provide several ecosystem services that significantly affect people’s quality of life. Jansen [

29] emphasized the significance of traditional knowledge on land use practices for the maintenance of agrobiodiversity, autochthonous breeds and crop varieties, production of traditional products, architecture, gastronomy, and other services delivered by traditional farmers and shepherds. Economically valuing and socially acknowledging these services has been mentioned in the reviewed papers as a method that could contribute to the preservation of these systems and the benefits associated with them. However, the financial support measures allocated to farmers are primarily related to environmental protection without considering the important socio-cultural services related to the multifunctionality and sustainability of agriculture. In Andalusia, economic compensation is granted to farmers that use their animals, that graze certain areas under specific conditions, to prevent forest fires [

31]. Along the same lines, agri-environmental and climate measures, payments for organic farming and Natura 2000 support under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) regime have been developed by the European countries to remunerate the provision of certain ecosystem services. To resolve such issues, Cejudo-Garcίa et al. [

33] stresses the importance of local participation and stakeholder involvement in the planning and decision-making, through participatory processes, for the development of strategies that connect the natural and cultural heritage and strengthen economic activities inside the PAs.

Among the actions aiming at promoting the multifunctional and sustainable character of agriculture, “high quality food products” has been indicated in our review as an important economic dimension that can add value to local products and improve the quality of life of the communities that live inside the PAs. The creation of a brand for these products could be a way to strengthen the synergy among the ecological, socio-cultural, aesthetic, and gastronomical values associated with low-intensity farming systems and biodiversity rich, agricultural landscapes [

34] that characterise most European PAs. Product differentiation based on high quality standards and/or geographical origin of production has been proved a highly competitive strategy that can empower farmers, give them the opportunity to improve their profitability, generate added value and lead to the creation of niche markets [

40].

According to the reviewed literature, local and high-quality food products produced in PAs can use the positive image and capture the unique nature of the place and thereby can promote authenticity [

8] and naturalness [

10]. Thus, considered to be “iconic” products with emotional qualities due to their special characteristics [

34,

35]. Especially for PAs that are known for their ecological value and are attractive to tourists, a labelling scheme can promote local products and raise awareness on the regional identity and quality characteristics of the products for both local people and tourists. Labelled agri-food products with a PA brand logo can valorise the qualifications linked to their socio-ecological attributes which can be translated into higher prices with additional multiplier effects for the regional economy [

17,

35]. Besides the economic impact and consumer awareness, the implementation of production and labelling standards can contribute to the achievement of environmental goals like landscape management and biodiversity conservation [

34].

Many studies have indicated the increasing consumer interest in locally produced food and regional certification labels that promote quality products with specialised characteristics [

28]. Other studies have concluded that among the most important quality criteria to holiday making are a beautiful landscape and good food [

34]. More recently, and probably influenced by the ecological crisis of the last decade, the general shopping habits of consumers with more social and environmental awareness has been raised substantially. The two revied papers on consumers’ perceptions in food quality products with a PA label, provide results that support this trend. Temperini et al. [

10] pointed out that younger people and women are more environmentally aware, and they trust more and are willing to pay for food quality labelled products with the national parks’ brand. Ferrari [

8] indicated in her study that there is an increasing awareness towards the important role of PAs and effective branding policies for PAs’ agri-food products could promote local image, identity, and sustainability objectives.

To date, the EU has gradually developed several food quality schemes with the aim of improving farmers’ and producers’ income, enable them to market their products better through diversification and ensure that certain characteristics are clear to consumers. The main EU quality labels (PDO, PGI, TSG) protect the names of specific products and promote their unique characteristics, linked to their geographical origin and the traditional know-how involved in their manufacture. In addition, one more optional quality term, the “mountain product”, introduced with the Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products. The label “mountain product” highlights the specificities of a product, made in mountain areas with natural constraints. The specific policy framework of the EU quality schemes gives an emphasis on the development of quality labels to strengthen local food supply chains by linking territorial quality associations and/or production specifications with product branding, promoting these labels among the European Countries [

41]. It is also an important feature of the European Green Deal, launched in 2020 with the objective to build a fairer, healthier, and more environmentally friendly food system by 2030 [

42].

However, recent studies show that there is an attitude-behaviour gap between consumers’ green rhetoric and purchasing habits. While consumer appreciation and awareness towards sustainable food labels, local products, and culinary traditions have been raised significantly, the actual purchasing behaviour towards food quality schemes among European consumers remains low [

43]. Generally, the market shares of EU food quality products remain modest and marginal, and are not well known by consumers, who often do not understand or pay attention to the labels [

44]. Moreover, the abundance of labels, product-certifying systems and symbols can create confusion and scepticism to consumers towards food products that promote sustainable attributes, including those that are genuinely more environmentally friendly [

45]. These issues are also addressed in the EU’s new Farm to Fork strategy that aims to accelerate the transition to more sustainable food systems. Part of the strategy is to increase and improve food information to consumers to help them make more informed, healthy, and sustainable food choices and enforce rules against misleading information. In addition, it aims to promote sustainability food labelling schemes and a higher uptake of sustainability standards [

42].

With special focus on the European PAs, that are symbols of naturalness, wilderness, ecological integrity, biodiversity, and quality goods [

8], there is no official recognition of a quality label by the EU legislation. The accreditation of a PA brand is mainly based on national regulations that provide the opportunity to local farms, food companies and other enterprises to certify their products and use their own brand name as a marketing tool [

10,

17]. Additionally, the Natura 2000 label can be used to support the production and selling of agri-food products produced and/or manufactured inside Natura 2000 areas while respecting and supporting the conservation goals of the area. The promotion and labelling of sustainable farming in Natura 2000 sites are usually based on regional nature conservation projects [

46].

According to Renting et al. [

47], the creation, operation and evolution of short food supply chains and the development of a clear label profile is a process with highly differentiated outcomes. It depends on several factors, linked with variations in farming practices, territorial attributes, cultural traditions, organisational structures, institutional and policy support but as well on the consumers’ perceptions and trust in the products. Based on the reviewed studies, the successful examples of the labelled agri-food products in the Rhön and Entlebuch Biosphere Reserves, indicated that the development and establishment of the labels followed a bottom-up approach which required a lot of time, effort, and synergies between different activities and among various actors to achieve good results [

17,

35].

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to shed some light on the link between sustainable farming practices and certification/labelling schemes of agri-food products with a PA logo in the achievement of environmental and socio-economic development goals. To this end, we used the existing literature to examine the sustainability dimensions and impacts investigated in the reviewed papers and the methodological approaches adopted by the researchers. It was clear that academic research on the issue is scarce. We acknowledge, however, limitations in our research and the possibility of existing related studies in other languages.

Our findings suggest that the European PAs are facing today very complex and highly diverse challenges. Profit maximization, social factors, technological improvements, and market forces have changed farm management structures inside PAs, leading towards the gradual abandonment of the less productive and marginalised areas and intensification and specialization of farming systems in the most fertile and easily accessible areas. Therefore, protection objectives should include the development of tools and activities that promote in a combined, integrated way the important socio-cultural services related to the multifunctionality and sustainability of agriculture, in addition to environmental protection.

A quality scheme or label alone for the agri-food products of the European PAs cannot guarantee a success in delivering sustainable development. However, it is a rural development process that involves multiple functions that can be linked to environmental improvements and positive socio-economic changes. These services should be better quantified, and factors linked to the effective development of a labelling scheme should be thoroughly analysed. Any research on the impacts of labelled agri-food products of PAs at farm, farm household, regional and societal level can contribute to our further understanding of the morphology and dynamics of this tool. Future lines of research will require to consider the interrelations and additional effects emerging from the labelling/certification of high quality agri-food products with a PA logo. It is also important to understand consumer demands, current trends and changing shopping habits towards agri-food products with more social and environmental characteristics. Finally, specific reference should be made on the research gap identified by our review on the environmental impacts associated with the development of such labelling schemes. Particularly, there is a need for more research on the influence of a label in the effective management of PAs and the achievement of environmental goals like the conservation of farmland biodiversity and preservation of cultural landscapes.