Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

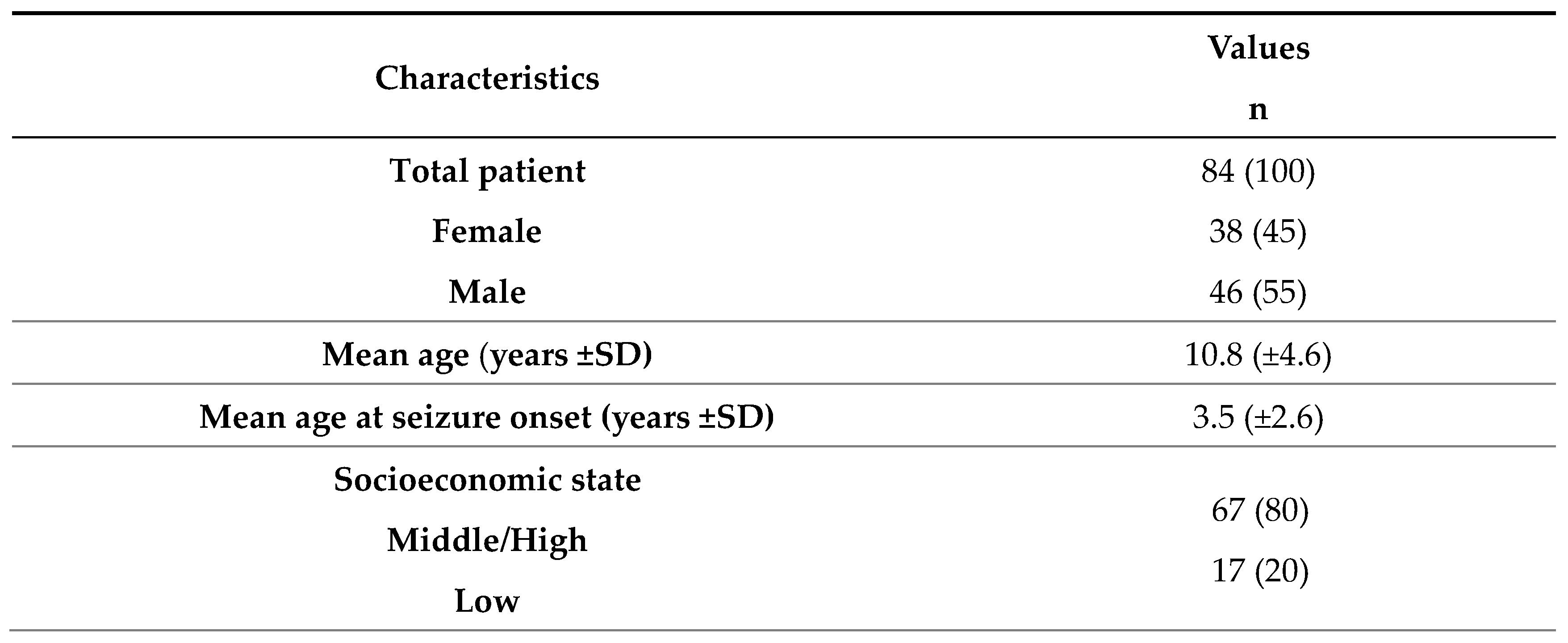

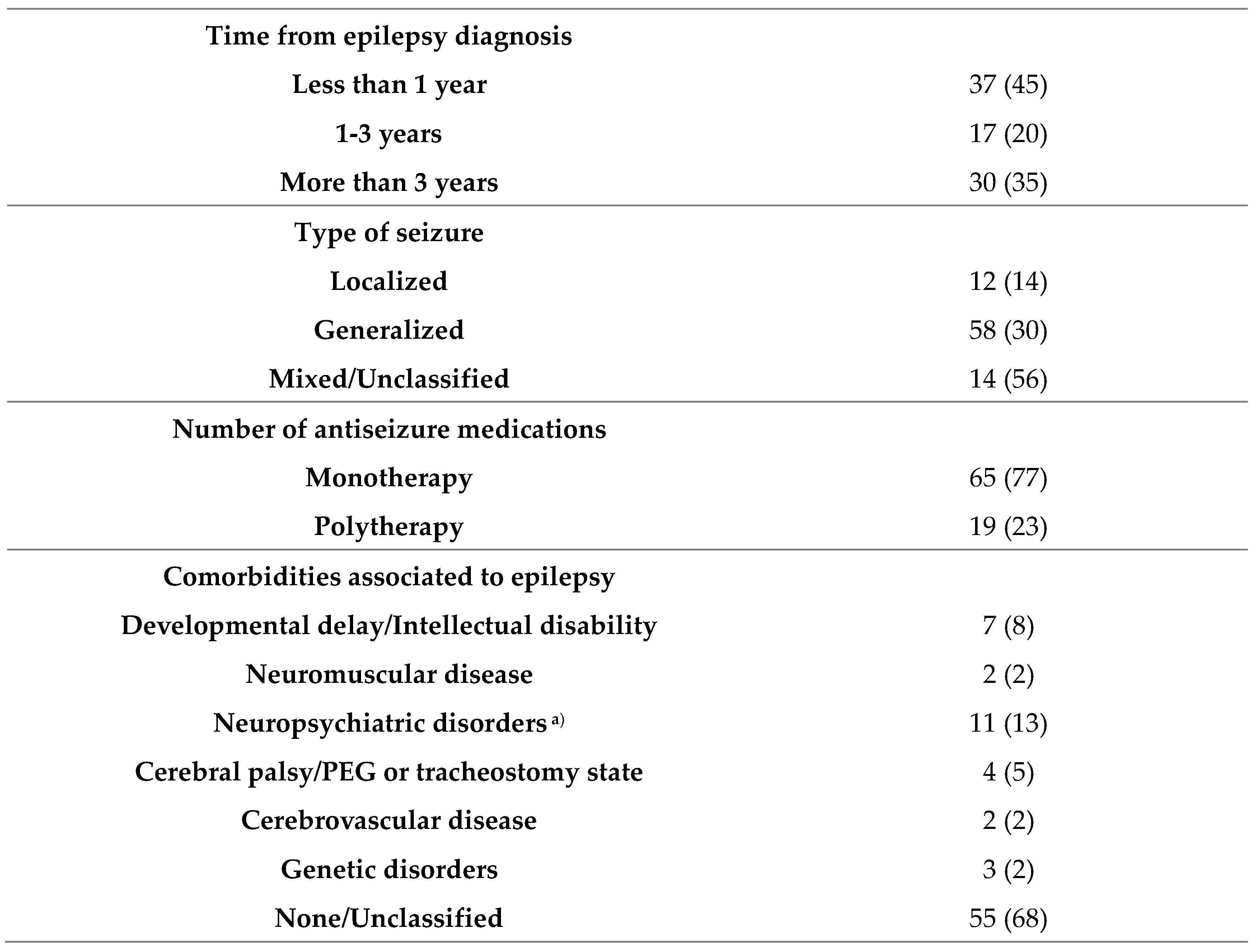

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of children with epilepsy before COVID-19 pandemic

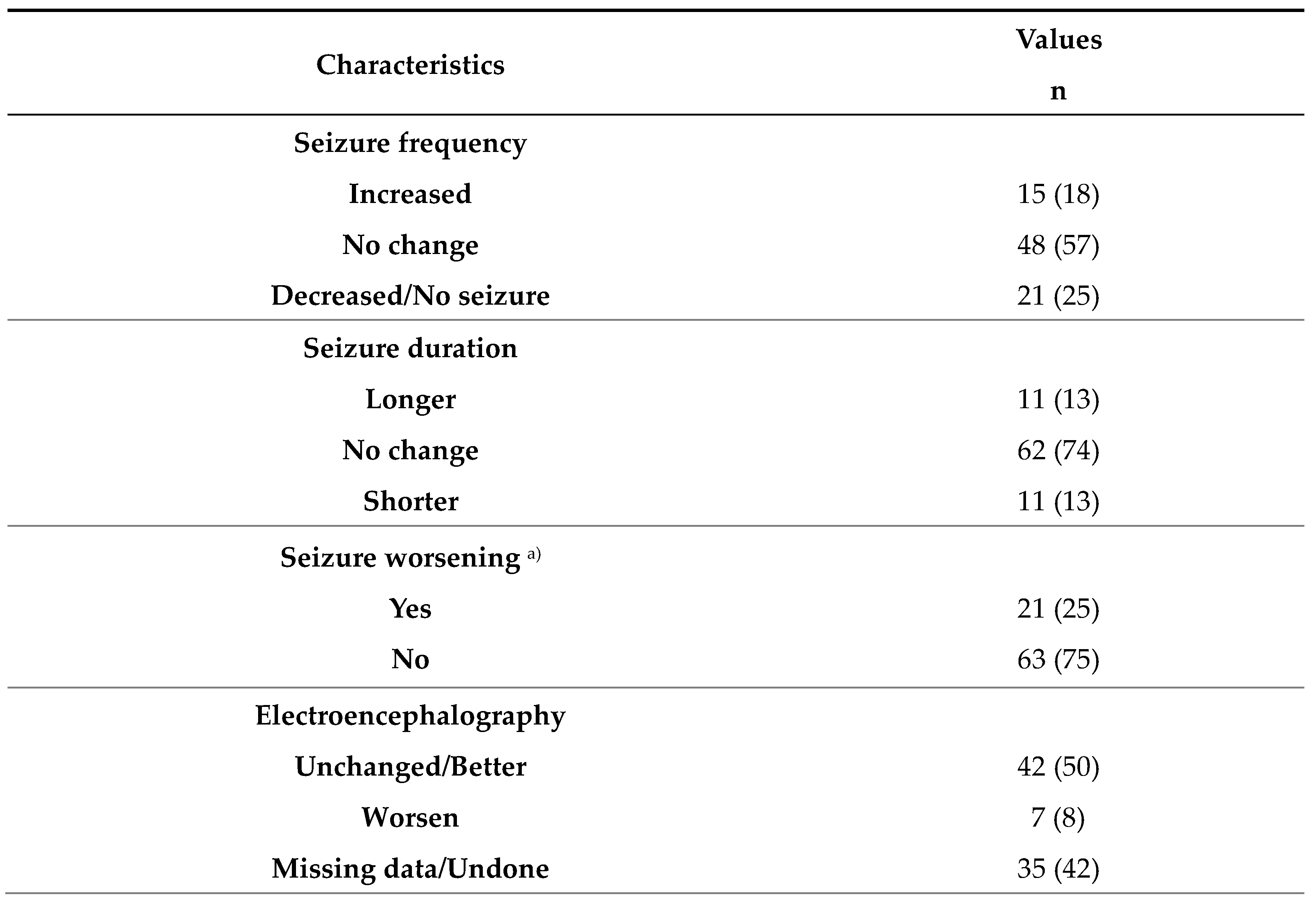

3.2. Seizure changes during the COVID-19 pandemic era

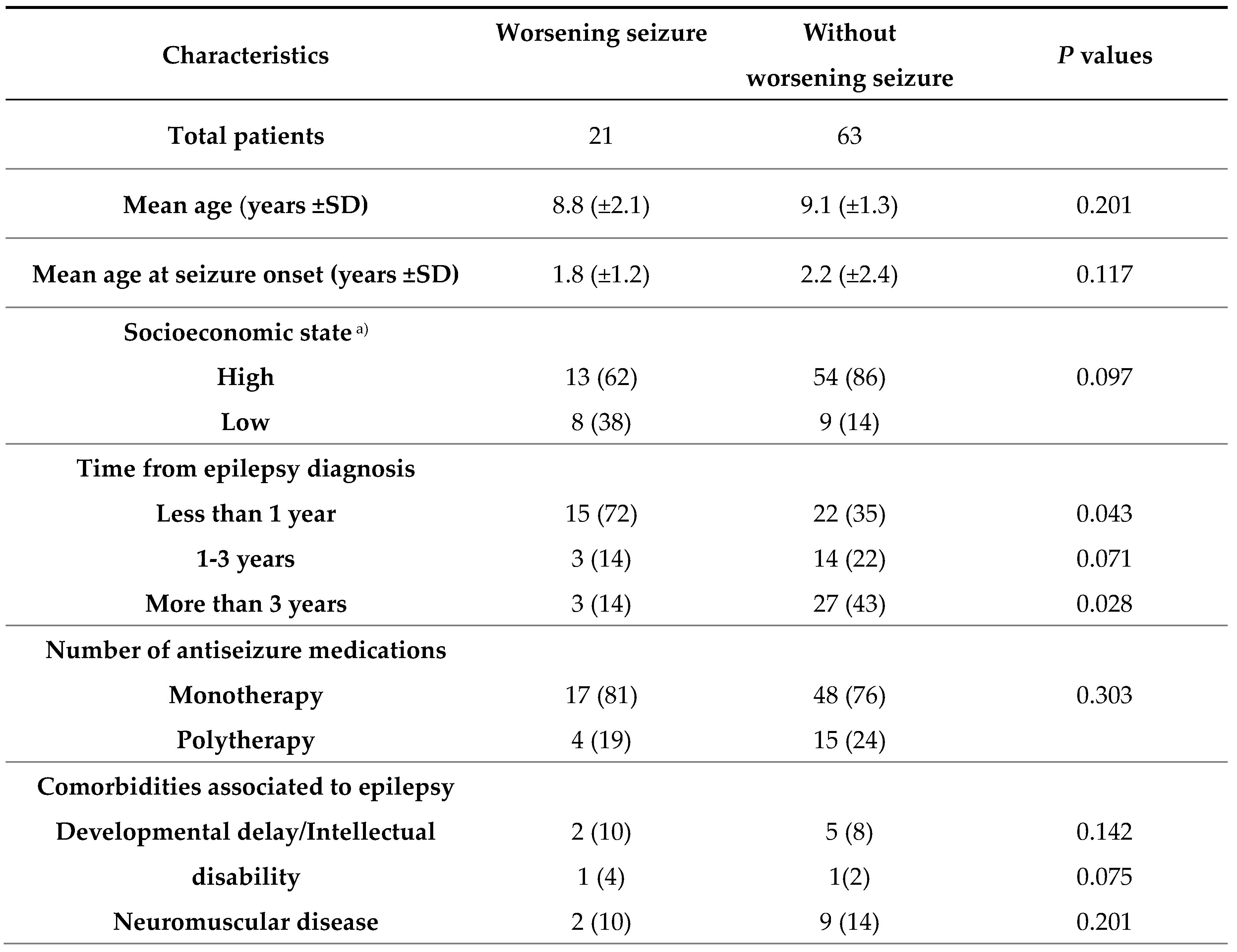

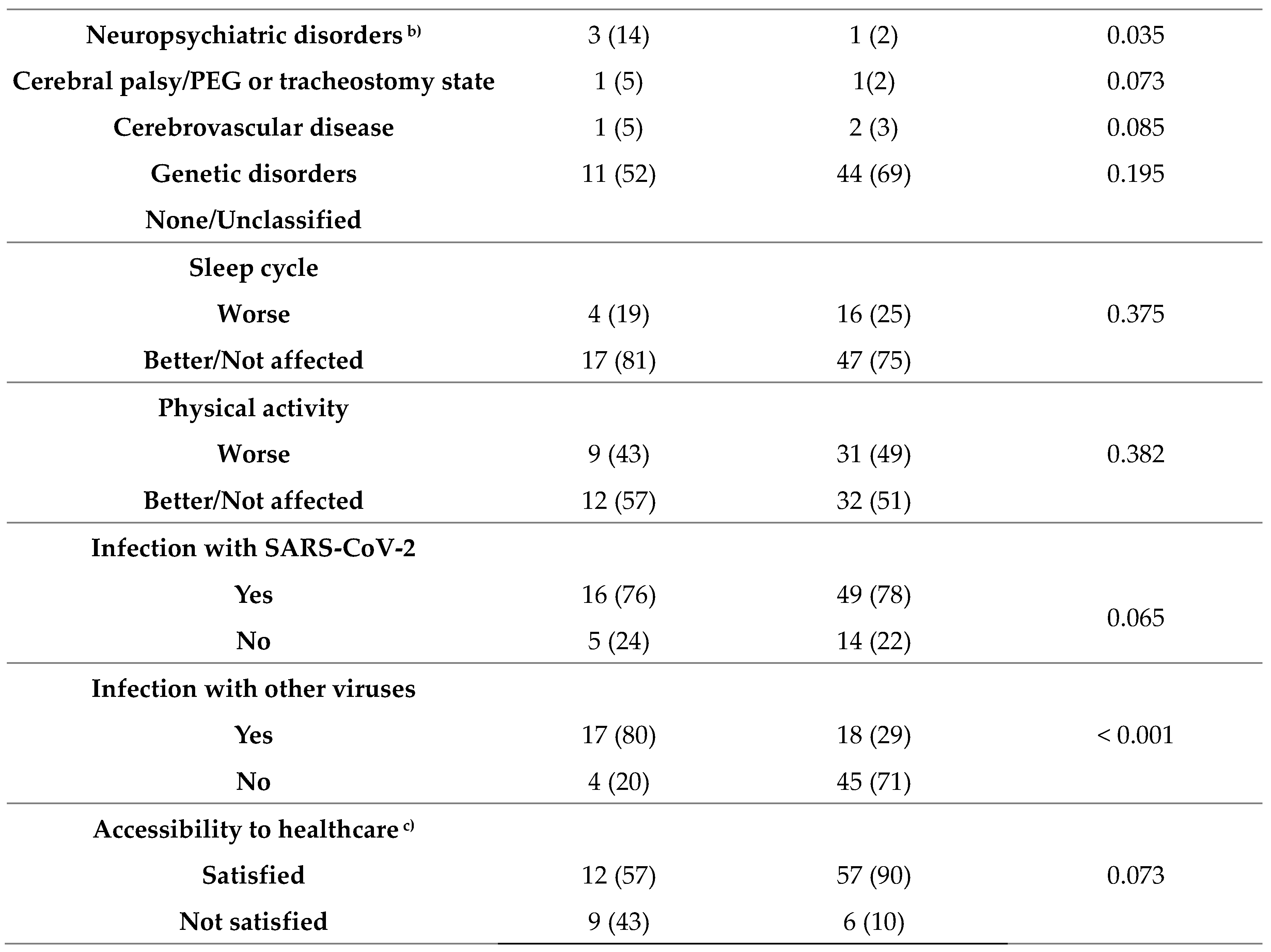

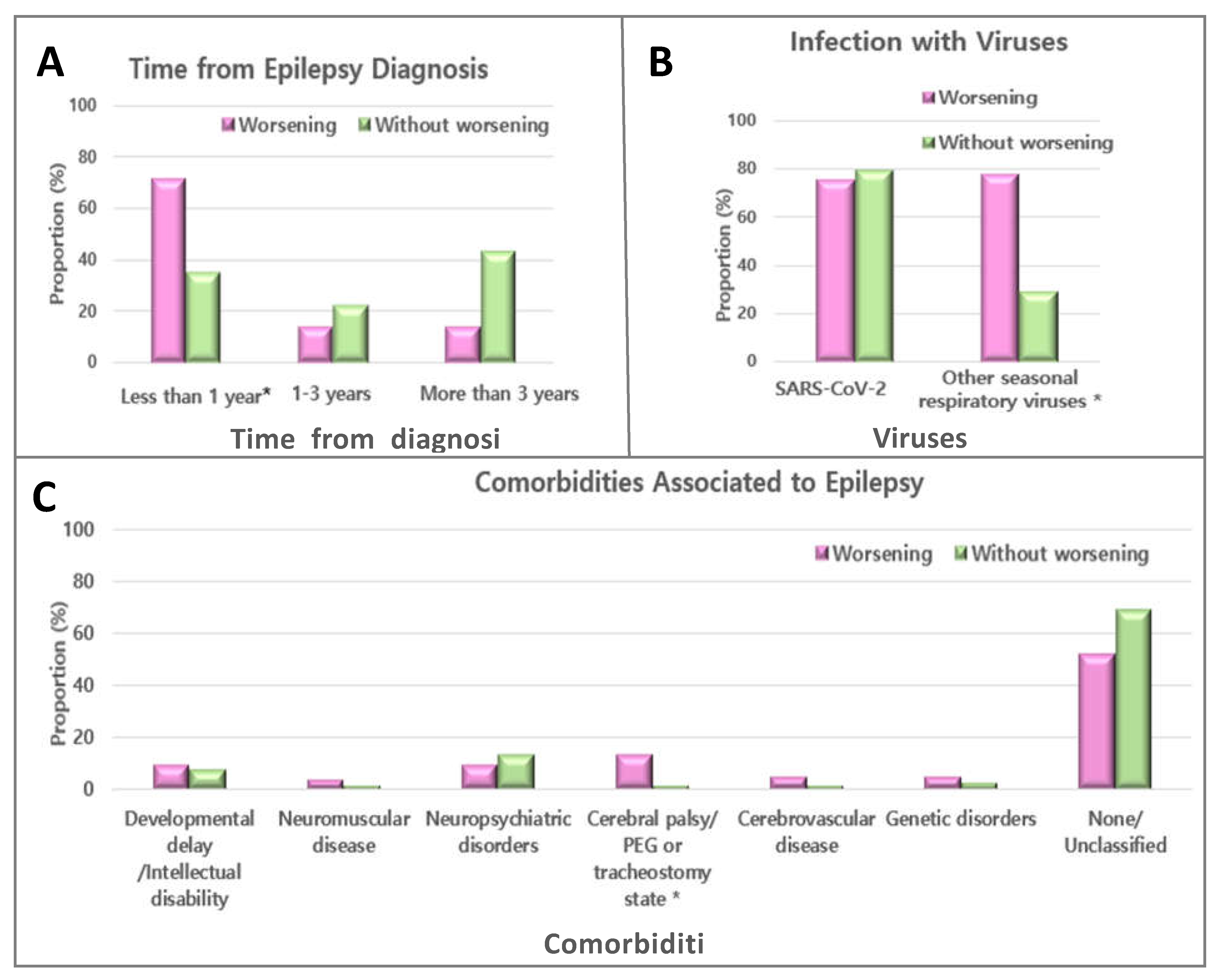

3.3. Risk factors of significantly worsening seizures during the COVID-19 pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Mannan, O.; Taylor, H.; Donner, E.J.; Sutcliffe, A.G. A systematic review of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in childhood. Epilepsy Behav 2019, 90, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagar, A.; Falcone, T. Psychiatric Comorbidities in Pediatric Epilepsy. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2020, 22, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, V.; Kendrick, D.; Sayal, K.; Thomas, S.L.; West, J. Injury among children and young adults with epilepsy. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiest, K.M.; Birbeck, G.L.; Jacoby, A.; Jette, N. Stigma in epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2014, 14, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, C.E.; Beghi, E. The economic cost of epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsia 2002, 43 Suppl 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Deng, L.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Cheung, C.W.; Xia, Z. Review of the Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Gen Intern Med 2020, 35, 1545–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhotani, A.; Siddiqui, M.I.; Almuntashri, F.; Baothman, R. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on seizure control and self-reported stress on patient with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2020, 112, 107323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D. , et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Xiong, W.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; Li, N.; Mu, J.; Guo, J.; Li, W.; Wang, G. , et al. New onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in coronavirus disease 2019: A retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia 2020, 61, e49–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, T.; Bisulli, F.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Rocamora, R. Did the COVID-19 pandemic silence the needs of people with epilepsy? Epileptic Disord 2020, 22, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, R.T.; Wijaya, V.O.; Jody, A.A.; Nunsio, P.N.; Buana, R.B. Persistent neurological manifestations in long COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health 2022, 15, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.S.; Acevedo, C.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Bogacz, A.; Cross, J.H.; Elger, C.E.; Engel, J., Jr.; Forsgren, L.; French, J.A.; Glynn, M. , et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.S.; Cross, J.H.; French, J.A.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F.E.; Lagae, L.; Moshe, S.L.; Peltola, J.; Roulet Perez, E. , et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Momani, M.; Almomani, B.A.; Sweidan, P.; Al-Qudah, A.; Aburahma, S.; Arafeh, Y. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric patients with epilepsy in Jordan: The caregiver perspective. Seizure 2021, 92, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Larsen, A.; Gonzalez-Villar, E.; Diaz-Maroto, I.; Layos-Romero, A.; Martinez-Martin, A.; Alcahut-Rodriguez, C.; Grande-Martin, A.; Sopelana-Garay, D. Influence of the COVID-19 outbreak in people with epilepsy: Analysis of a Spanish population (EPICOVID registry). Epilepsy Behav 2020, 112, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilhoto, L.M.; Mosini, A.C.; Susemihl, M.A.; Pinto, L.F. COVID-19 and epilepsy: How are people with epilepsy in Brazil? Epilepsy Behav 2021, 122, 108115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assenza, G.; Lanzone, J.; Brigo, F.; Coppola, A.; Di Gennaro, G.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Ricci, L.; Romigi, A.; Tombini, M.; Mecarelli, O. Epilepsy Care in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: Risk Factors for Seizure Worsening. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, C.; Jia, Y.; Li, G.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, K.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhu, S. COVID-19 outbreak: The impact of stress on seizures in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivisano, M.; Specchio, N.; Pietrafusa, N.; Calabrese, C.; Ferretti, A.; Ricci, R.; Renzetti, T.; Raponi, M.; Vigevano, F. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric patients with epilepsy - The caregiver perspective. Epilepsy Behav 2020, 113, 107527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengard, J.L.; Donato, J.; Ferastraoaru, V.; Zhao, D.; Molinero, I.; Boro, A.; Gursky, J.; Correa, D.J.; Galanopoulou, A.S.; Hung, C. , et al. Seizure control, stress, and access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: The patient perspective. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.T.; Huang, F.L.; Ting, P.J.; Chang, C.C.; Chen, P.Y. The epidemiological features of pediatric viral respiratory infection during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2022, 55, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirrell, E.C.; Grinspan, Z.M.; Knupp, K.G.; Jiang, Y.; Hammeed, B.; Mytinger, J.R.; Patel, A.D.; Nabbout, R.; Specchio, N.; Cross, J.H. , et al. Care Delivery for Children With Epilepsy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Survey of Clinicians. J Child Neurol 2020, 35, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assenza, G.; Lanzone, J.; Ricci, L.; Boscarino, M.; Tombini, M.; Galimberti, C.A.; Alvisi, L.; Tassi, L.; Broglia, L.; Di Lazzaro, V. , et al. Electroencephalography at the time of Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Neurol Sci 2020, 41, 1999–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, D.; Elumalai, V.; Desai, V.C.; Hoyt, M.L. Conceptualization and implementation of an interdisciplinary clinic for children with drug-resistant epilepsy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav 2021, 125, 108403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blottner, S.; Bertram, R.; Pitra, C. [Species specific motility patterns of hyperactivated mammalian spermatozoa and quantitative analysis of the hyperactivation of bull spermatozoa]. Andrologia 1989, 21, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonello, M.; Michael, B.D.; Solomon, T. Infective Causes of Epilepsy. Semin Neurol 2015, 35, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Lang, B.; Aronica, E. Immunity and Inflammation in Epilepsy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 6, a022699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, A.W.C.; Keezer, M.R.; Sander, J.W. Epilepsy is a neurological and a systemic disorder. Epilepsy Behav 2018, 78, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillanpaa, M.; Saarinen, M.M.; Karrasch, M.; Schmidt, D.; Hermann, B.P. Neurocognition in childhood epilepsy: Impact on mortality and complete seizure remission 50 years later. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrini, S.; Koepp, M.J.; Gandhi, S.; Rickman, H.M.; Shin, G.Y.; Houlihan, C.F.; Anders-Cannon, J.; Silvennoinen, K.; Xiao, F.; Zagaglia, S. , et al. Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities for people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2021, 115, 107602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.A.; Brodie, M.J.; Caraballo, R.; Devinsky, O.; Ding, D.; Jehi, L.; Jette, N.; Kanner, A.; Modi, A.C.; Newton, C.R. , et al. Keeping people with epilepsy safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology 2020, 94, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aledo-Serrano, A.; Mingorance, A.; Jimenez-Huete, A.; Toledano, R.; Garcia-Morales, I.; Anciones, C.; Gil-Nagel, A. Genetic epilepsies and COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from the caregiver perspective. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, E.; Quintana, M.; Lallana, S.; Luis Restrepo, J.; Abraira, L.; Santamarina, E.; Seijo-Raposo, I.; Toledo, M. Epilepsy in time of COVID-19: A survey-based study. Acta Neurol Scand 2020, 142, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribot, R.; Kanner, A.M. Neurobiologic properties of mood disorders may have an impact on epilepsy: Should this motivate neurologists to screen for this psychiatric comorbidity in these patients? Epilepsy Behav 2019, 98, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millevert, C.; Van Hees, S.; Siewe Fodjo, J.N.; Wijtvliet, V.; Faria de Moura Villela, E.; Rosso, B.; Gil-Nagel, A.; Weckhuysen, S.; Colebunders, R. Impact of COVID-19 on the lives and psychosocial well-being of persons with epilepsy during the third trimester of the pandemic: Results from an international, online survey. Epilepsy Behav 2021, 116, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuno, N.; Besset, A.; Ritchie, K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2005, 66, 1254–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsawh, H.J.; Stein, M.B.; Belik, S.L.; Jacobi, F.; Sareen, J. Relationship of anxiety disorders, sleep quality, and functional impairment in a community sample. J Psychiatr Res 2009, 43, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.B.; Belik, S.L.; Jacobi, F.; Sareen, J. Impairment associated with sleep problems in the community: relationship to physical and mental health comorbidity. Psychosom Med 2008, 70, 913–919. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, J.; Ashby, S.; Hallab, A.; Ding, D.; Andraus, M.; Dugan, P.; Perucca, P.; Costello, D.; French, J.A.; O'Brien, T.J. , et al. Evaluating risk to people with epilepsy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary findings from the COV-E study. Epilepsy Behav 2021, 115, 107658. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Duan, P.; Yao, L.; Hou, H. Shiftwork-Mediated Disruptions of Circadian Rhythms and Sleep Homeostasis Cause Serious Health Problems. Int J Genomics 2018, 2018, 8576890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, J.T.; DeWolfe, J.L. Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Epilepsy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2018, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.; Aung, T.; Geng, Y.; Wang, S. Epilepsy and Its Interaction With Sleep and Circadian Rhythm. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, M.Y.; Lim, K.S.; Fong, S.L.; Khor, S.B.; Tan, C.T. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with epilepsy: An interventional study using early physical consultation. Epilepsy Behav 2021, 122, 108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arida, R.M.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; da Silva, A.C.; Scorza, F.A. Physical activity and epilepsy: proven and predicted benefits. Sports Med 2008, 38, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arida, R.M.; de Almeida, A.C.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Scorza, F.A. Experimental and clinical findings from physical exercise as complementary therapy for epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2013, 26, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, Y.; Michael-Gayego, A.; Rivkin, M.; Levinson, L.; Wolf, D.G.; Nir-Paz, R. Decreased prevalence rate of respiratory pathogens in hospitalized patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: possible role for public health containment measures? Clin Microbiol Infect 2020, 27, 811–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Song, K.H.; Kim, E.S.; Park, J.S.; Jung, J.; Ahn, S.; Jeong, E.K.; Park, H.; Kim, H.B. Impact of Public Health Interventions on Seasonal Influenza Activity During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Korea. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, e132–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.P.; Chu, I.Y.; Yeh, M.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lee, C.L.; Lin, H.H.; Chan, Y.J.; Chen, H.P. Differentiating impacts of non-pharmaceutical interventions on non-coronavirus disease-2019 respiratory viral infections: Hospital-based retrospective observational study in Taiwan. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2021, 15, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, J.S.; Sikazwe, C.; Xie, R.; Deng, Y.M.; Sullivan, S.G.; Michie, A.; Levy, A.; Cutmore, E.; Blyth, C.C.; Britton, P.N. , et al. Off-season RSV epidemics in Australia after easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.P.; Vermeulen, F.; Debeer, A.; Lagrou, K.; Smits, A. Impact of COVID-19 on viral respiratory infection epidemiology in young children: A single-center analysis. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 931242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.T.; Lau, Y.C.; Shan, S.; Ryu, S.; Du, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, X.K.; Chen, D.; Xiong, J.; Tae, J. , et al. Prediction of upcoming global infection burden of influenza seasons after relaxation of public health and social measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2022, 10, e1612–e1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).