1. Introduction

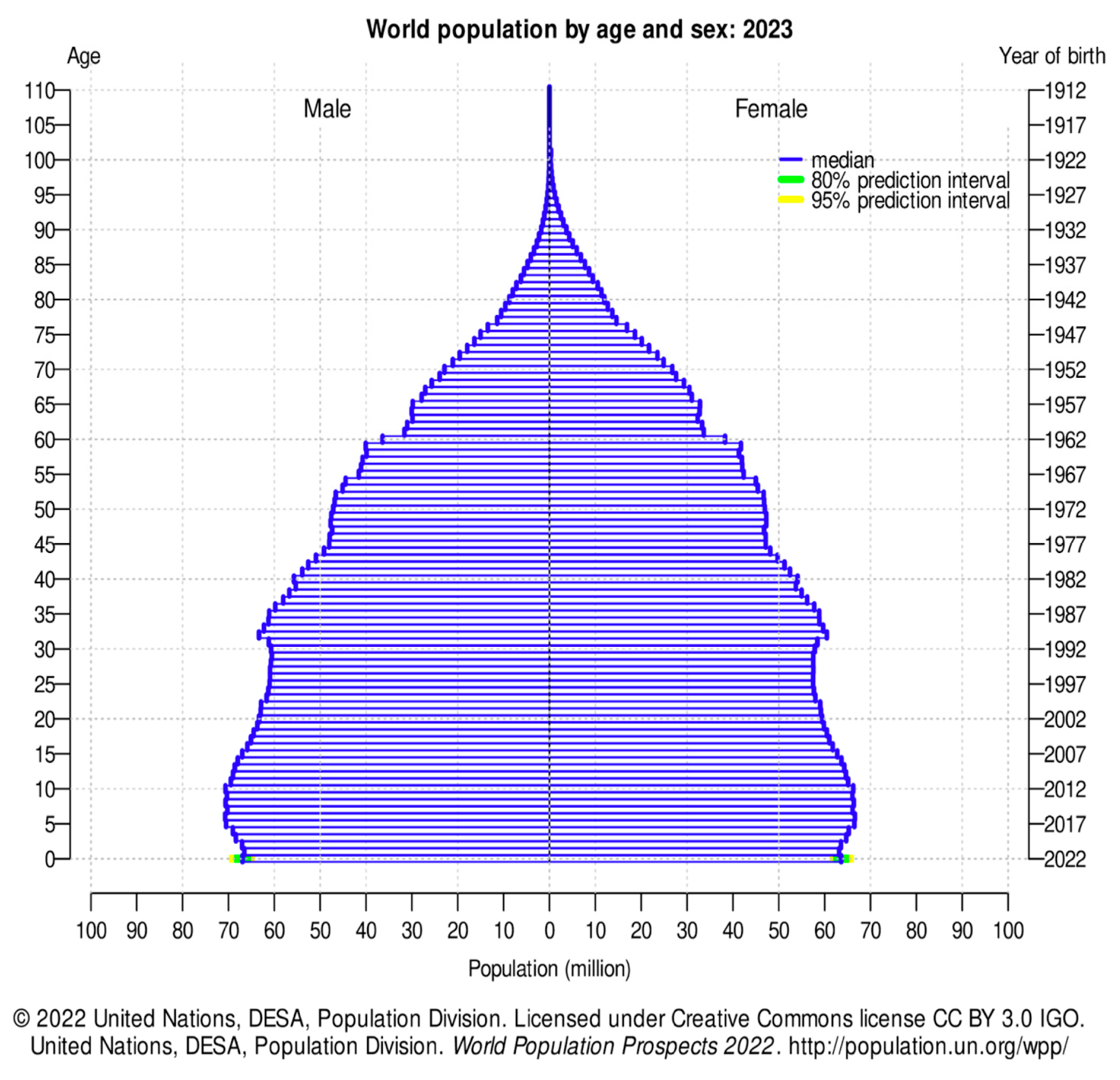

Life expectancy is invariably increasing worldwide. Data available in literature confirm this trend: the median age has gone from 22.2 years in 1950 to 30.2 in 2022.

In the USA the median age was 29.3 in 1950 and became 37.9 in 2022. In Europe it has gone from 27.8 years in 1950 to 41.9 in 2022; in Italy from 27.5 years in 1950 to 47.3 in 2022. (1)

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines 65 y.o as the age of transition to the status of “elderly”. While people over the age of 60 were considered elderly by WHO until 1984 (2), now it has shifted to 65 years old.

The elderly patient presents age-related morphological and histological changes of the oral cavity, regarding both hard and soft tissues (3) (4) due to reduced elasticity, limited turnover and higher susceptibility to certain pathogens. (5) (6) Also, the effects of pharmacological therapies, primarily anti-resorptive but also chemotherapy, should not be underestimated.

Literature displays many studies regarding the specific pathologies of the oral cavity in elderly patients, both regarding self-sufficient and institutionalized older population. (7) (5)

The main modifications of the oral cavity of the elderly are:

Reduced taste function and swallowing efficiency (9) (10);

Bone atrophy as a result of tooth loss;

The thinning of the oral mucosa and the decrease of its keratinization;

Reduced elasticity and permeability of connective tissue;

Atrophy of adipose tissue;

Changes in the vessels: small arteries and arterioles undergo atherosclerosis processes and the number of capillaries decreases;

The atrophy of the salivary glands which, added to the action of some drugs, often determines an overall reduction in the basic salivary flow;

The increase of carious lesions, favored in the elderly by gingival recession (11);

The progressive tooth loss due to the high prevalence of periodontal disease.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study was to analyze the series of patients over 65 who were treated by our Unit of Pathology and Oral Medicine and Odontostomatological Diagnostics between 2020 and 2022 for the diagnosis and therapy of diseases of the oral cavity.

All patients aged 65 years or older that were addressed to our center by private practitioners or other spoke hospitals for a suspicion of oral lesion or for dental evaluation in anticipation of cardiac surgery, anti-resorptive drugs intake, chemotherapy, radiotherapy of the head neck district or transplantation (kidney, liver, bone marrow or heart), were included. Patients who were not diagnosed with any oral lesion following the examinations (8 patients) were excluded from the study.

For each patient, in a Microsoft Excel database, the following data were collected: age, sex, diagnosis and location of the lesion (or the reason for dental evaluation) and any in-depth examinations to which the patient has been subjected (imaging, laboratory, histopathological).

Oral lesions have been classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Dentistry and Stomatology (ICD-DA) (12) and the World Health Organization Cancer Classification (2022) (13).

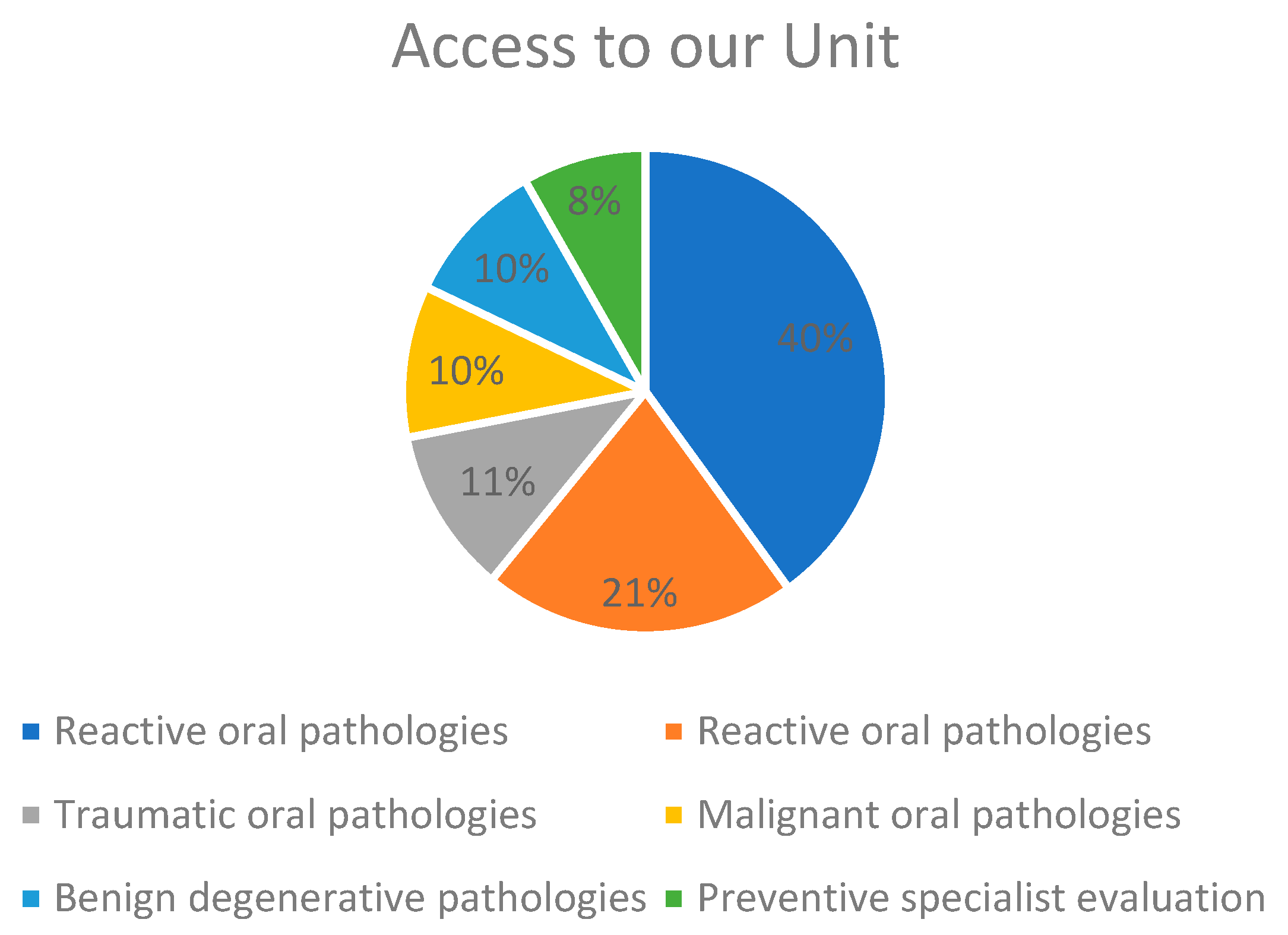

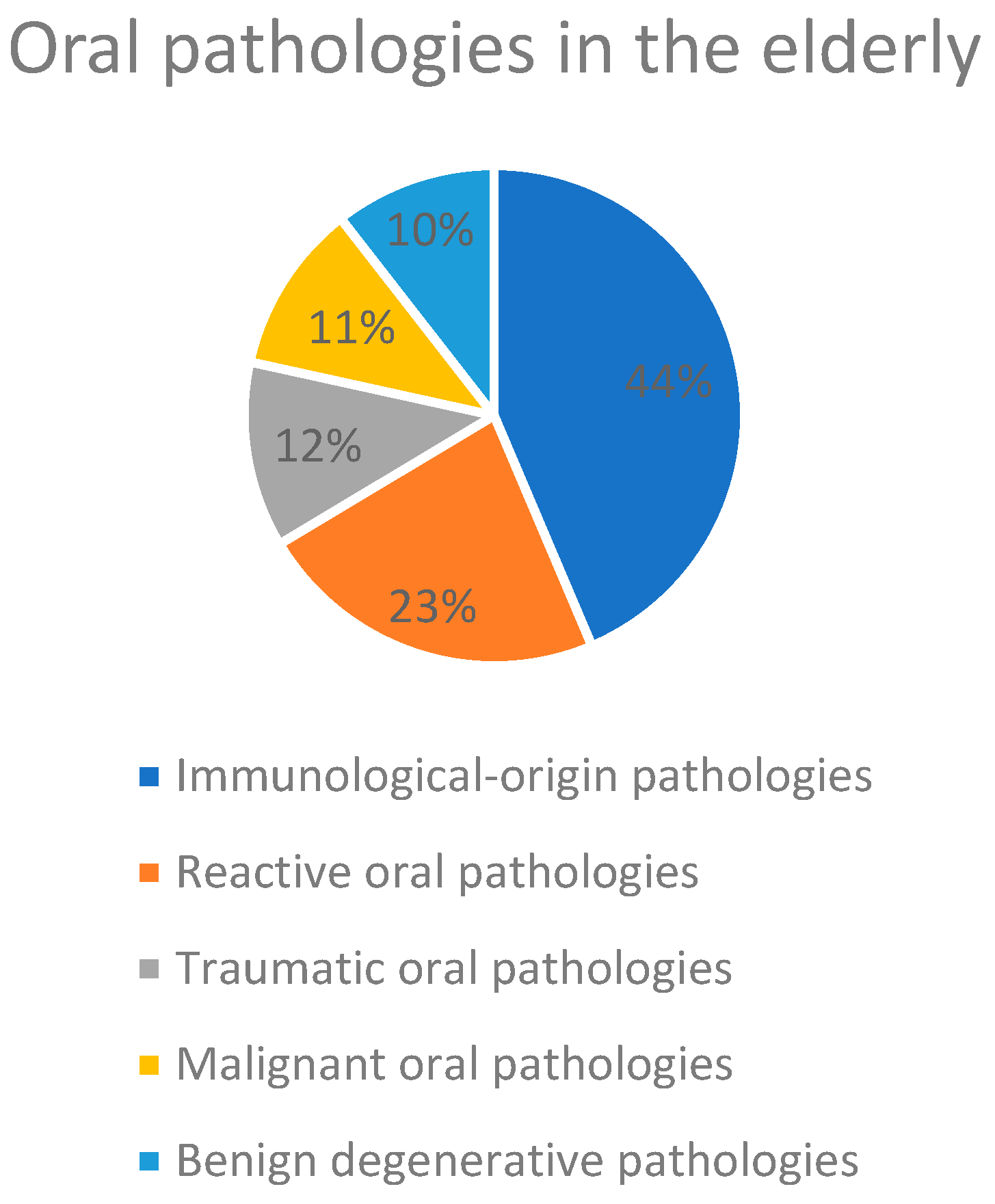

The analysis was conducted by dividing oral lesions into 5 groups depending on the etiology: reactive, immunological, traumatic, benign degenerative and malignant degenerative. The sixth group consisted of patients undergoing preventive dental evaluation.

3. Results

The study included 435 patients whose median age was 74 years; 153 were male and 282 were female. 91 of them received a diagnosis of pathology of reactive origin, 174 of immunological origin, 48 of traumatic origin and 86 were diagnosed with degenerative pathologies (42 benign and 44 malignant).

A group of patients, 36 to be precise, went to our Unit for preventive specialist evaluation.

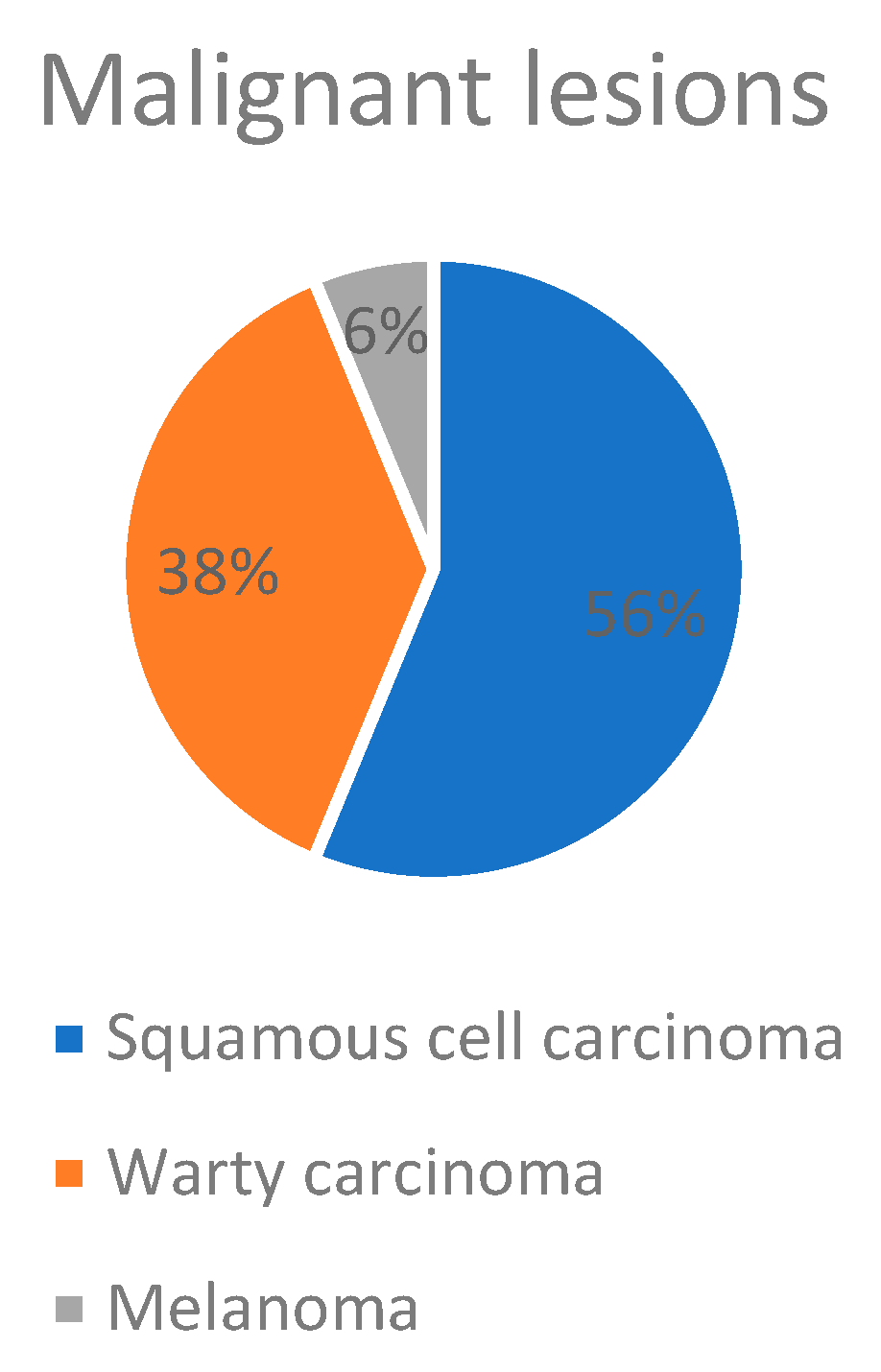

Among the pathologies of malignant degenerative origin, 16 carcinomas of the oral cavity have been diagnosed, including:

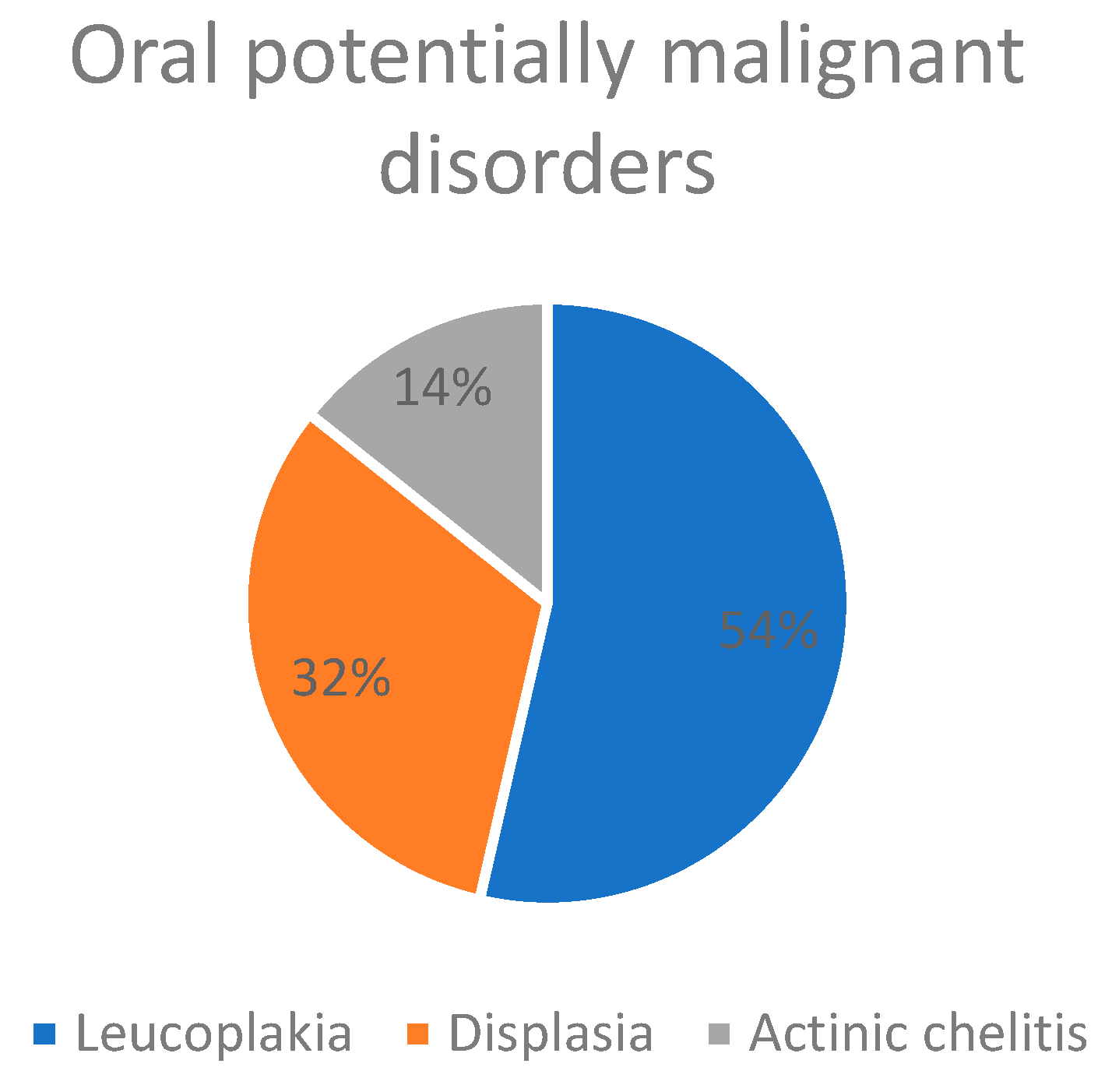

Among the patients analyzed in this study, 28 potentially malignant lesions were detected including:

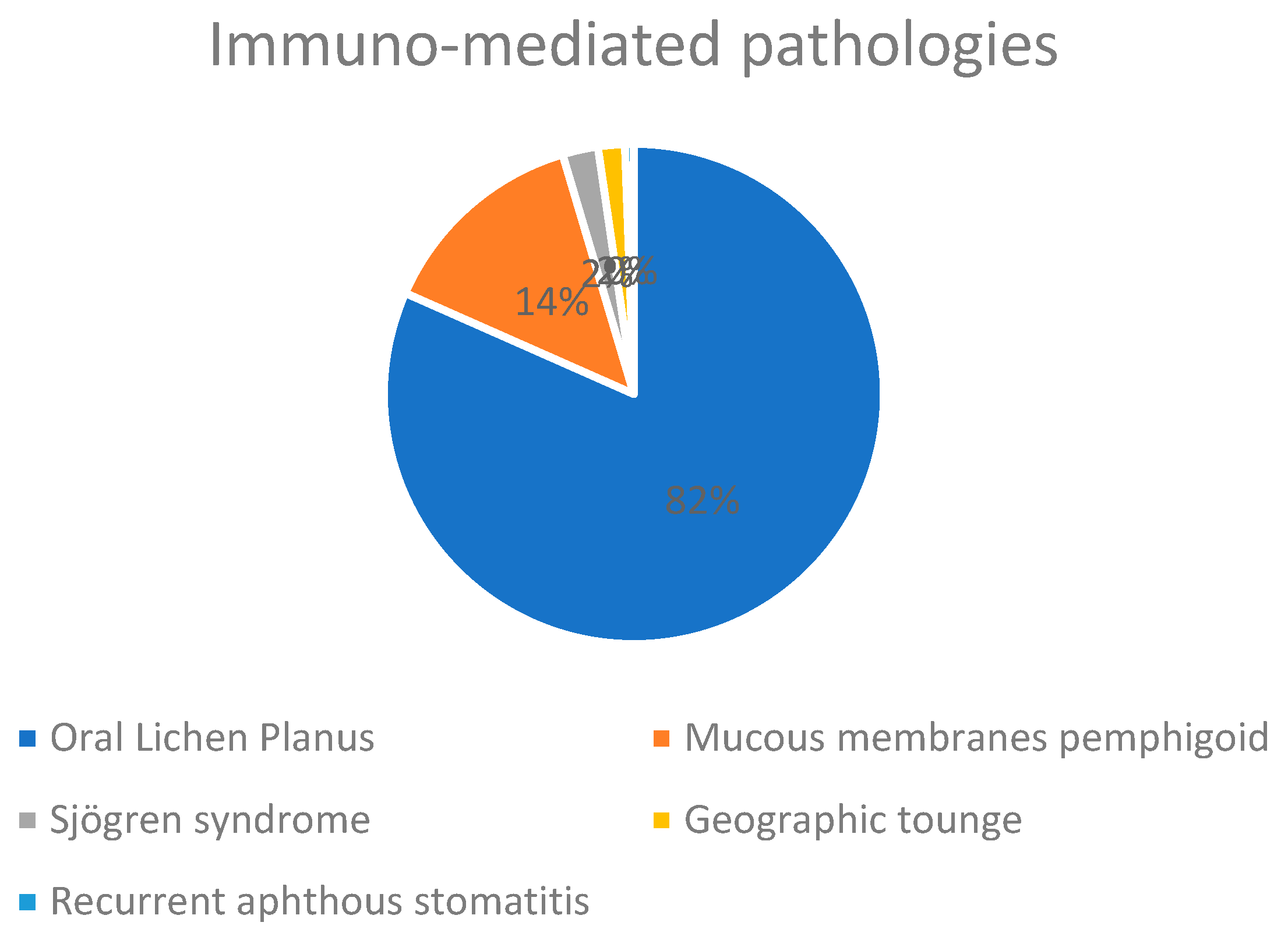

Among the patients analyzed in this study, 142 were affected by Oral Lichen Planus (OLP), a disease of immune-mediated origin that has a malignant transformation rate around 1%. 6 of the patients with Lichen Planus underwent an additional biopsy in the six-monthly check-ups for suspected dysplasia and 3 cases tested positive for high-grade dysplasia.

Mucous membranes pemphigoid was another frequent pathology of immunological origin among the patients of this study, and it was diagnosed by histological examination in 24 patients.

Among the pathologies of immunological origin, 4 elderly patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and 1 elderly patient suffering from recurrent aphthous stomatitis are being treated at our Unit. Blood chemistry tests were required for both of these diseases. Lastly, 3 patients came to our attention for suspicious lesions of the tongue, but after an accurate clinical examination they were diagnosed with a typical anatomical variation known as “geographic tongue”. These lesions appeared in fact as erythematous areas surrounded by a characteristic migratory cercine.

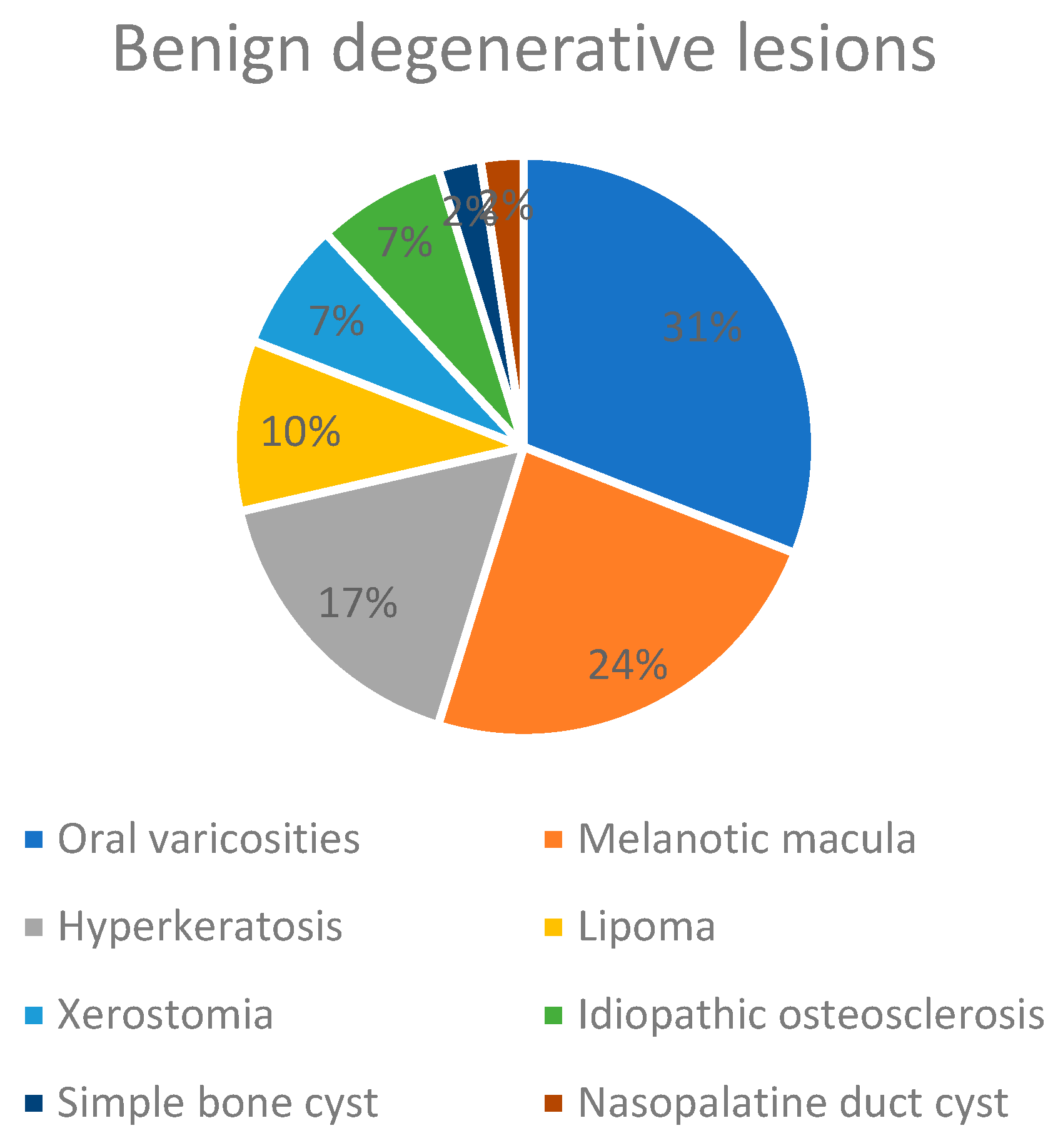

Among the diseases of benign degenerative origin, lingual varicosities (13 patients) and melanotic macule (10 patients) are most frequently distinguished.

In lower frequency among the pathologies of benign degenerative origin have been detected:

7 cases of hyperkeratosis;

4 cases of lipoma;

3 cases of xerostomia;

3 cases of idiopathic osteosclerosis;

1 case of Simple Bone Cyst;

1 case of nasopalatine duct cyst.

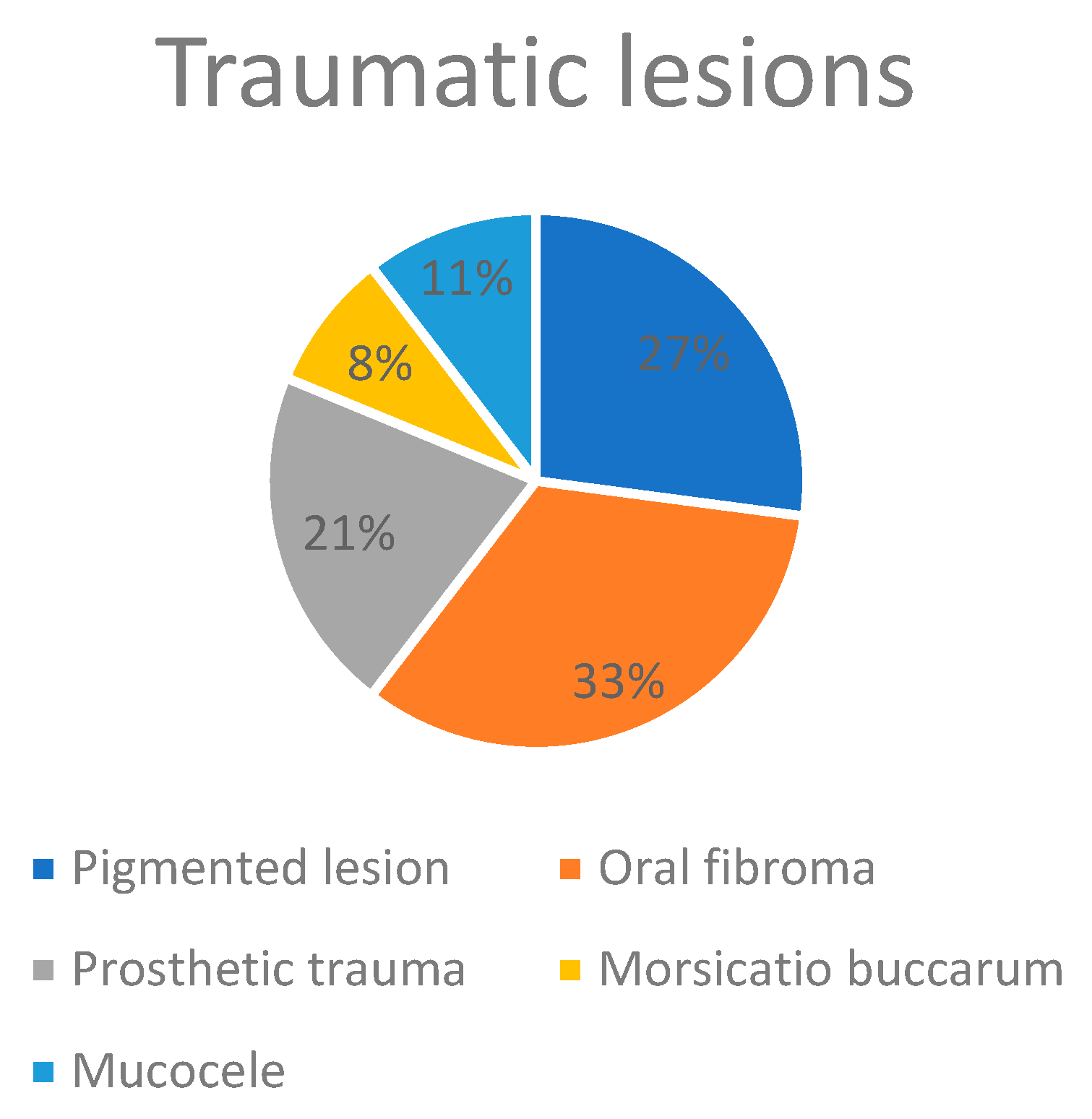

48 patients came to our center for pathologies of traumatic origin, such as:

13 pigmented lesions;

16 traumatic fibromas;

10 prosthetic trauma;

4 morsicatio buccarum;

5 mucoceles.

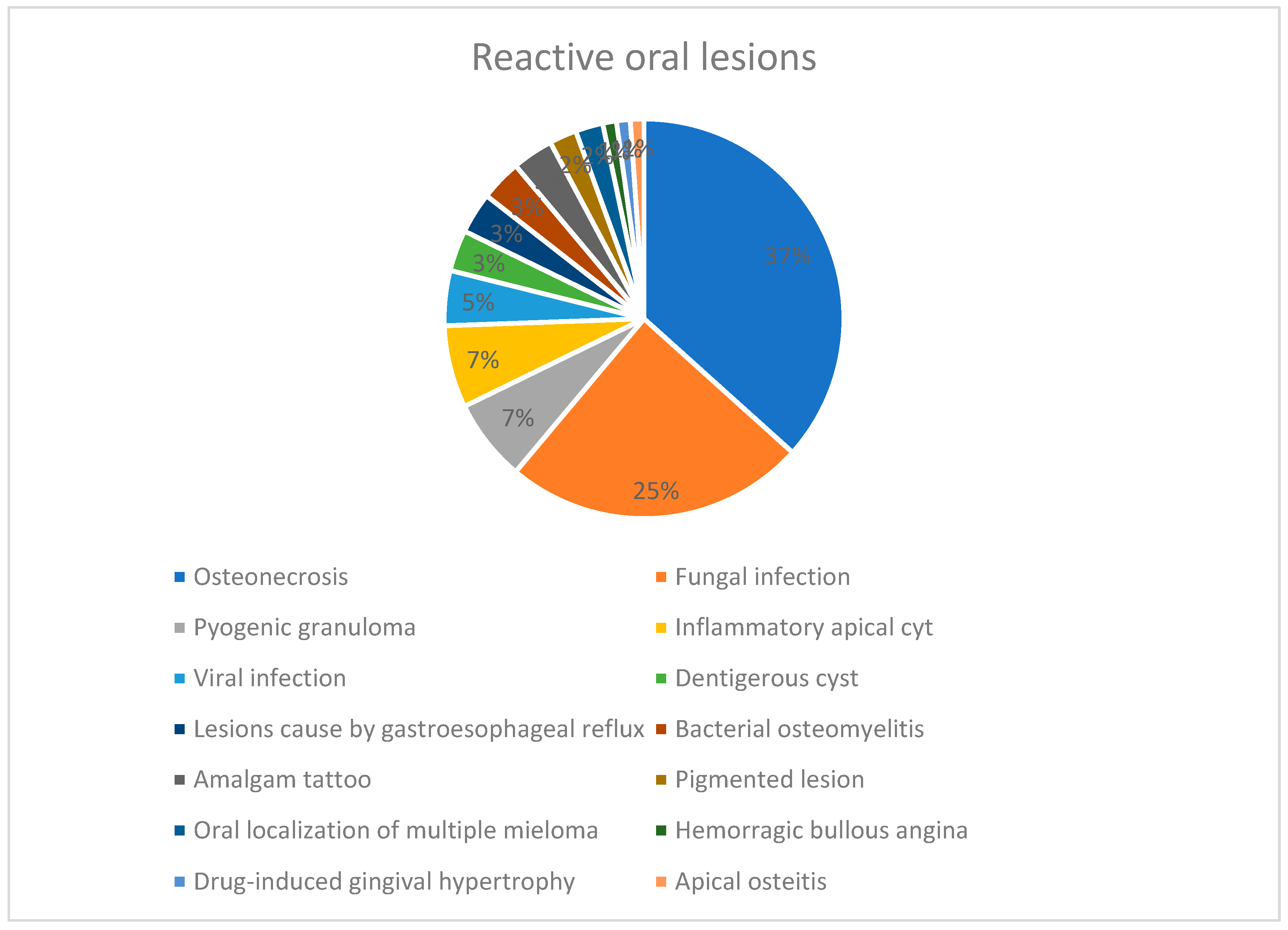

At last, 22% of the patients involved in this study presented at our center for diseases of reactive origin including:

33 osteonecrosis;

22 fungal infections;

6 pyogenic granulomas;

6 inflammatory apical cysts;

4 viral infections;

3 dentigerous cyst;

3 lesions caused by gastroesophageal reflux;

3 bacterial osteomyelitis;

3 amalgam tattoos;

3 pigmented lesions;

2 oral manifestations of multiple mieloma;

A hemorrhagic bullous angina;

A gingival hyperplasia related to antihypertensive drugs;

An apical osteitis.

29 are the patients analyzed by us in this study for the primary prevention of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) and they have been cataloged as “preventive specialist evaluations”. Specifically, 22 patients were examined before starting bisphosphonate therapy for diseases such as multiple myeloma, osteoporosis and metastases of breast cancer, thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer and esophageal adenocarcinoma. The remaining 7 patients were already being treated with ONJ associated drugs and were sent to our department by colleagues for tooth extractions.

The remaining preventive specialist evaluations were performed in patients who were candidates for cardiac surgery, chemotherapy, head neck radiotherapy and transplantation (kidney, liver, bone marrow and heart).

The 22 fungal infections tested positive for Candida albicans or other strains of the genus Candida on cyto/microbiological examination. Among the subjects in this study, three different forms of oral candidiasis were detected:

3 cases of median rhomboid glossitis;

3 cases of chronic hyperplastic candidiasis;

3 cases of angular cheilitis.

In order to achieve a correct diagnosis, all patients underwent a careful clinical examination to establish a diagnostic hypotheses, that was later confirmed or refuted thanks to:

Histological exam in 320 cases;

Radiographic imaging in 88 cases;

Cytological test in 15 cases;

Microbiological tests in 7 cases;

Blood chemistry tests in 20 cases;

Molecular typing tests in 9 cases.

4. Discussion

Median values (and not arithmetic means) were used to describe the mean age values, because in the case of an asymmetric distribution such as the age of the population, they are more representative.

No etiologically based classification about the pathologies of the oral cavity is available in Literature.

Therefore, our study group has defined a new differentiation of the pathologies of this district based on their origin dividing them into reactive, traumatic, immunological, degenerative benign and malignant.

Indeed, oral fibroma has been considered a pathology of reactive origin, as it is still uncertain if it is a real tumor, but it seems to better represent a hyperplastic lesion of the fibrous connective tissue induced by irritation or trauma. (14)

The category of lesions most frequently found in this study are those of immunological origin, in particular oral Lichen Planus, unlike most similar studies in the literature, which report a preponderance of lesions of reactive origin in elderly patients. (15) (16) (17) (18) (19)

Data that emerge from this study coincide with those of current literature regarding the detection of squamous cell carcinoma as the most frequent malignant pathology in the elderly patients (15)(16)(18)(19) and likewise leukoplakia as the main potentially malignant lesion (5)(20)(21), the rarity of neoplastic diseases affecting the salivary glands (not emerged in our study) (15) and the high prevalence of oral varicosities among benign neoplastic pathologies. (8) (22) (23) (24) (25) (26) (27)

Tumors of the oral cavity are so-called head and neck cancers. In Italy every year about 4,000 new cases of mouth cancer are diagnosed, more frequent in men than in women. The incidence in Italy is 7 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. This type of cancer is rare in young people, but the incidence increases with age and it peaks in people over 70. For all oral cancers the main risk factors are tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. The coexistence of these two factors multiplies the risk of developing neoplastic lesions of the mouth. (28)

Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) is the most frequent malignant tumor of the oral cavity with a higher prevalence in men than women. Clinical aspects range from a white or red lesion to an ulcerative area and a swelling of papillary or warty appearance. Treatment of OCSCC is based on the size of the primary tumor, the anatomical site, the extension to the lymph nodes and any distant metastases.

Verrucous carcinoma is a low-malignant variant of oral cancer, with a better prognosis than squamous cell carcinoma and the highest prevalence is in males over 60. On physical examination it presents with white exophytic lesions with a papillary or warty surface. First choice therapy is surgical excision that can also be performed by laser.

Oral melanoma is very rare. Clinically it appears as a dark brown or black pigmented macula with irregular and indistinct margins that tends to expand. First choice therapy is radical surgical excision; Complete margin-negative resection is necessary, and it should be at least 4-5 cm from the edges of the lesion. (29) (30)

Early cancer detection is fundamental for the survival and life-quality of oncologic patients. Hence derives the importance of early detection of oral potentially malignant lesions.

Elderly patients undergo a progressive deterioration of the functions of the immune system (immunosenescence), which translates into a reduced ability to defend against microorganisms on one hand and on the other an increased tendency to develop autoimmune diseases also in oral cavity. (25) (27)

Patients with OLP and mucous membranes Pemphigoid were visited frequently to monitor oral hygiene conditions, dental and periodontal situation and for the prescription of corticosteroids.

The “American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Criteria for the Classification of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome” of 2016 were strictly applied for the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Oral varicosities are dilations of venous vessels that develop in the oral cavity of elderly patients, particularly on the tongue’s ventral surface, lips and vestibular mucosa. They have the appearance of dark blue nodules, of mobile consistency and usually do not require any treatment.

Melanotic macule are flat pigmented areas of the oral mucosa caused by a deposit of melanin, without an increased number of melanocytes. All melanotic macules in this study were investigated by biopsy to confirm the clinical diagnosis and exclude the presence of nevi, melanoacanthoma or melanoma. (29) (30)

In elderly patients many pathologies are often related to a low level of oral hygiene and prosthetics trauma.

The oral pigmented lesions resolved spontaneously or after removal of the traumatic factor. Also in this case the most frequent sites were the buccal mucosa and the tongue.

Traumatic fibromas were treated with surgical excision followed by histological examination for diagnostic confirmation. The most frequent sites were the tongue, lips and buccal mucosa.

The lesions caused by incongruous prosthetic, detected most frequently in lower edentulous saddles, were resolved by advising the patient to abstain from the use of prosthetics during the night.

Morsicatio buccarum, most often detected in the tongue and buccal mucosa, were observed 1 and 2 weeks apart to confirm their etiology, following removal of the traumatic factor.

The mucoceles of the lower lip were biopsied and did not recur after removal of the traumatic factor.

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) is a serious side effect that occurs in some patients undergoing anti-resorptive drugs (such as bisphosphonates or denosumab), antiangiogenic agents or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. (31) (32) (33) (34) (35) (36) (37) The prevalence of this chronic necrosis of the mandible and maxilla is increasing among elderly patients, especially in women.

In order to prevent ONJ it is essential to educate elderly patients taking the above medications to maintain a proper oral hygiene and subject them to routine dental check-ups. (38) (39)

The diagnosis of MRONJ is achieved through the application of a diagnostic work-flow, which starts from the clinical suspicion (based on signs and symptoms, but also on the evaluation of systematic and local risk factors) and must necessarily be integrated with the radiological investigations (OPT/intraoral radiographs and CBCT, respectively first and second level investigations). The execution of a bone biopsy should be performed in the diagnostic phase only in case of suspicion of metastases from other solid tumors in the mandibular/maxillary site, or during dental avulsion in case the presence of pre-existing MRONJ is suspected. (30) (40)

The MRONJ cases diagnosed in our center occurred more frequently in patients suffering from oncological pathologies (in particular Multiple Myeloma) and treated pharmacologically with zolendronate. Our operating unit deals with MRONJ prevention at multiple levels:

- -

As primary prevention: the control of local risk factors related to MRONJ is carried out both before and while taking the drugs;

- -

As secondary prevention: clinical/radiographic signs and/or symptoms associated with an early stage of MRONJ (therefore hopefully credible and/or easily treatable) are sought.

Candida is a component of the normal microbiota of the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract. To make a diagnosis of oral candidiasis, a positive culture test to C. albicans is not sufficient, but symptoms and clinical signs associated with it are necessary. In this study, 3 different types of oral manifestations of oral candidiasis were diagnosed: median rhomboid glossitis, chronic hyperplastic candidiasis and angular cheilitis.

Median rhomboid glossitis is clinically observed as an erythematous area on the midpoint area of the posterior third of the lingual dorsum. It is diamond shaped and the surface can be smooth or lobulated.

Hyperplastic chronic candidiasis occurs in the form of plaques strongly adhered to the mucosa, which cannot be removed by scraping. In this case, a biopsy may be needed if there is no response to antifungal treatment. This form of candidiasis has in fact been associated with epithelial dysplasia of various degrees, especially in the non-homogeneous form.

Angular cheilitis is mainly observed in elderly patients with prostheses, as in the cases included in this study, and is characterized by erythema, fissure and desquamation of labial commissures. (29) (30)

There are conflicting articles about how predisposing factors (such as advanced age, the use of removable dentures and poor oral hygiene) interact with each other and favour the proliferation of mycete and therefore trigger the infection. Some papers substain that Candida is an age related infection rather then prosthesis related,(41); others, however, claim the opposite (42), (43). The use of prostheses and increasing age alone cannot fully explain the high prevalence of oral candidiasis in geriatric patients, which varies between 34 and 51 % (44). In fact, it has been shown that even some systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus (45), immunosuppression (41) and some pharmacological therapies (antibiotics and corticosteroids) (46) (47) favor the development of these opportunistic infections (48).

These systemic conditions also significantly influence the onset of xerostomia.

Dry oral cavity is one of the most common symptoms in elderly patients, with 40% of frequency (49),(50), (51). There is evidence of a correlation between xerostomia and polypharmacotherapy. The definition of polypharmacotherapy mostly used indicates patients who chronically take 5 or more different active substances per day (52). Numerous studies show that dry mouth depends on the number of drugs, the duration of their use, their interactions and not specifically their type (53, 54, 55).

The presence of saliva is fundamental for taste perception, which is activated during the first phase of food intake. Geriatric patients also present with a gradual taste buds, neuromuscular control and muscle strength loss with a consequent reduction in chewing performance (56). Such conditions result in a significant impact on appetite that can eventually lead to malnutrition or eating disorders (57).

5. Conclusions

In the elderly, even a slight drop of the immune defenses, due to an alteration of the microbiota following antibiotic therapy, polypharmacotherapy, the presence of systemic diseases, or simply due to “elderly” age increases the probability of onset of oral lesions.

Oral health has a major impact on the daily life of an elderly patient. Some oral diseases, in fact, have negative effects on some systemic diseases such as neoplasms, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and respiratory infectious diseases.

The examination of oral mucosa in geriatric patients represents a diagnostic moment of fundamental importance to report lesions early, thus allowing easier prevention and treatment.

The exchange of information between oral pathology and other medical specialties is also fundamental to obtain clinical-diagnostic completeness and offer the elderly patient the most correct therapeutic, pharmacological and surgical protocols.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., C.F, and G.A.; methodology, C.B., C.F., G.A., and A.R.; software, A.R. C.F.; validation, C.B.; formal analysis, C.F., G.A., A.R.; investigation, C.F., G.A.; data curation, C.F., G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.F., G.A.; writing—review and editing, C.B., A.R.; visualization, C.B.; supervision, C.B.; project administration, C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Azienda Ospedale Università di padova (223n/AO/22).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations - Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- WHO Scientific Group on the Epidemiology of Aging. The Uses of Epidemiology in the Study of the Elderly. Technical. World Health Organization, editor. 1984. 84 p.

- Breustedt A. Age-induced changes in the oral mucosa and their therapeutic consequences. nt Dent J. 1983;33:272–80.

- Vigild M. Oral mucosal lesions among institutionalized elderly in Denmark. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:309–13.

- Pindborg JJ. Oral cancer and precancer as diseases of the aged. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1978;6: 300–307.

- Fleishman R, Peles DB, Pisanti S. Oral mucosal lesions among elderly in Israel. J Dent Res 1985; 64: 831–836.

- Scott J, Cheah SB. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in the elderly in a surgical biopsy population: a retrospective analysis of 4042 cases. Gerontology 1989;8: 73–78.

- Lin HC, Corbet EF, Lo EC. Oral mucosal lesions in adult Chinese. J Dent Res 2001; 80: 1486–1490.

- Boyce JM, Shone GR. Effects of ageing on smell and taste. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:239-41.

- Mojon P, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Rapin CH. Realtionship between oral health and nutrition in very old people. Age and aging 1999;28:463-468.

- Meneghim Mde C, Pereira AC, Silva FR. Prevalence of root caries and periodontal conditions in an elderly institutionalized population from Piracicaba-SP. Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2002 Jan-Mar;16(1):50-6.

- World Health Organization. ICD-DA: Application of the International Classification of Diseases to Dentistry and Stomatology. 3rd ed. World Health Organization. 1995.

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Head and neck tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2022. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 9).

- Neville B, Damm D, Allen C, Chi C. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis MO: Elsevier Inc; 2016. 878 p.

- Kononen, M., Ylipaavalniemi, P., Hietanen, J., Happonen, R.P., 1987. Oral diseases in the elderly in Finland as judged by biopsy. Compr. Gerontol. A 1, 106–108.

- Correa, L., Frigerio, M.L., Sousa, S.C., Novelli, M.D., 2006. Oral lesions in elderly population: a biopsy survey using 2250 histopathological records. Gerodontology 23, 48–54.

- Franklin, C.D., Jones, A.V., 2006. A survey of oral and maxillofacial pathology specimens submitted by general dental practitioners over a 30-year period. Br. Dent. J. 200, 447–450.

- Muzyka, B.C., Dehler, K.R., Brannon, R.B., 2009. Characterization of oral biopsies from a geriatric population. Gen. Dent. 57, 432–437.

- Carvalho Mde, V., Iglesias, D.P., do Nascimento, G.J., Sobral, A.P., 2011. Epidemiological study of 534 biopsies of oral mucosal lesions in elderly Brazilian patients. Gerodontology 28, 111–115.

- Rossi EP, Hirsch SA (1977). A survey of 4,793 oral lesions with emphasis on neoplasia and premalignancy. J Am Dent Assoc 94: 883–886.

- Silverglade LB, Stablein MJ (1988). Diagnostic survey of 9,000 biopsies from three age groups: under 60 years, 60–69 and over 70. Gerodontics 4: 285–288.

- Darwazeh AMG, Pillai K (1973). Prevalence of tongue lesions in 1013 Jordanian dental outpatients. Oral Surg 36: 34–38.

- Kaplan I, Moskona D (1990). A clinical survey of oral soft tissue lesions in institutionalized geriatric patients in Israel. Gerontology 9: 59–62.

- Kovac-Kavcic M, Skaleric U (2000). The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a population in Ljubljana, Slovania. J Oral Pathol Med 29: 331–335.

- Reichart PA, Schmidtberg W, Scheifele Ch (1996). Betel chewer’s mucosa in elderly Cambodian women. J Oral Pathol Med 25: 367–370.

- Jainkittivong A, Aneksuk V, Langlais RP. Oral mucosal conditions in elderly dental patients. Oral Dis. 2002 Jul;8(4):218-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodineau A, Folliguet M, Séguier S. Tissular senescence and modifications of oral ecosystem in the elderly: risk factors for mucosal pathologies. Curr Aging Sci. 2009 Jul;2(2):109-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agenzia Zoe, “Tumore della bocca”, airc.it, 20 marzo 2023. https://www.airc.it/cancro/informazioni-tumori/guida-ai-tumori/tumore-della-bocca.

- Ficarra G, Pini Prato GP. Manuale di patologia e medicina orale. 3. ed. Milano: McGraw- Hill; 2006.

- Biasotto M, Campisi G, Lodi G, Lo Muzio L, Mignogna MD, Montebugnoli L, et al. Patologia e medicina orale. Edra Publ; 2022. 528 p.

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117.

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Mehrotra, B.; Rosenberg, T.J.; Engroff, S.L. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: A review of 63 cases. J. Oral Maxil. Surg. 2004, 62, 527–534.

- Marx, R.E.; Sawatari, Y.; Fortin, M.; Broumand, V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: Risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J. Oral Maxil. Surg. 2005, 63, 1567–1575.

- King, R.; Tanna, N.; Patel, V. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw unrelated to bisphosphonates and denosumab-a review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 289–299.

- Estilo, C.L.; Fornier, M.; Farooki, A.; Carlson, D.; Bohle, G., 3rd; Huryn, J.M. Osteonecrosis of the jaw related to bevacizumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4037–4038.

- van Cann, T.; Loyson, T.; Verbiest, A.; Clement, P.M.; Bechter, O.; Willems, L.; Spriet, I.; Coropciuc, R.; Politis, C.; Vandeweyer, R.O.; et al. Incidence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients treated with both bone resorption inhibitors and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 869–878.

- Hernandez, M.; Phulpin, B.; Mansuy, L.; Droz, D. Use of new targeted cancer therapies in children: Effects on dental development and risk of jaw osteonecrosis: A review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2017, 46, 321–326.

- Hsu KJ, Hsiao SY, Chen PH, Chen HS, Chen CM. Investigation of the Effectiveness of Surgical Treatment on Maxillary Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: A Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2021 Sep 29;10(19):4480. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bacci C, Cerrato A, Bardhi E, Frigo AC, Djaballah SA, Sivolella S. A retrospective study on the incidence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) associated with different preventive dental care modalities. Support Care Cancer. 2022 Feb;30(2):1723-1729. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cerrato A, Zanette G, Boccuto M, Angelini A, Valente M, Bacci C. Actinomyces and MRONJ: A retrospective study and a literature review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Nov;122(5):499-504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart SR, Joly S, Vargas K, Swails-Wenger J, Enger L, Soll DR. Natural defenses against Candida colonization breakdown in the oral cavities of the elderly. J Dent Res, 1999; 78: 857-68.

- Ikebe K, Morii K, Matsuda K, Hata K, Nokubi T. Association of candidal activity with denture use and salivary flow in symptom – free adults over 60 years. J Oral Rehabil, 2006; 33: 36-42.

- Radford DR, Challacombe SJ, Walter JD. Denture plaque and adherence of Candida albicans to denture-base materials in vivo and in vitro. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med, 1999; 10: 99-116.

- Rothan-Tondeur M, Lancien E, Pialleport T, Meaume S, Moulias R, Marzais M, Cambau E & Le Blanche AF. Prevalence of oropharyngeal candidiasis in geriatric inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 1741–174.

- Belazi M, Velegraki A, Fleva A, Gidarakou I, Papanaum L, Baka D, Danülidou N, Karamitos D. Candidal overgrowth in diabetic patients: potential predisposing. Mycoses, 2005; 48: 192-6.

- Peterson DE. Oral candidiasis. Clin Geriatr Med 1992; 8: 513– 527.

- Shay K, Truhlar MR & Renner RP. Oropharyngeal candidosis in the older patient. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45: 863–870.

- Webb BC, Thomas CJ, Willcox MD, Harly DW, Knox KW. Candida-associated denture stomatitis. Aetiology and management: a review. Part 2. Oral disease caused by Candida species. Aust Dent J, 1998; 43: 160-6.

- Lu, T.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Du, J.K.; Lin, Y.C.; Ho, P.S.; Lee, C.H.; Hu, C.Y.; Huang, H.L. Dysphagia and Masticatory Performance as a Mediator of the Xerostomia to Quality of Life Relation in the Older Population. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 521.

- Kho, H.S. Understanding of Xerostomia and Strategies for the Development of Artificial Saliva. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 17, 75–83.

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.G.; Moreno, K. Xerostomia Among Older Adults With Low Income: Nuisance or Warning? J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 58–65.

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What Is Polypharmacy? A Systematic Review of Definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230.

- Navazesh, M.; Brightman, V.J.; Pogoda, J.M. Relationship of Medical Status, Medications, and Salivary Flow Rates in Adults of Different Ages. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1996, 81, 172–176.

- Murray Thomson, W.; Chalmers, J.M.; John Spencer, A.; Slade, G.D.; Carter, K.D. A Longitudinal Study of Medication Exposure and Xerostomia among Older People. Gerodontology 2006, 23, 205–213.

- Fernandes, M.S.; Castelo, P.M.; Chaves, G.N.; Fernandes, J.P.S.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Zanato, L.E.; Gavião, M.B.D. Relationship between Polypharmacy, Xerostomia, Gustatory Sensitivity, and Swallowing Complaints in the Elderly: A Multidisciplinary Approach. J. Texture Stud. 2021, 52, 187–196.

- Emami, E.; de Souza, R.F.; Kabawat, M.; Feine, J.S. The Impact of Edentulism on Oral and General Health. Int. J. Dent. 2013, 2013, 498305.

- Samnieng, P.; Ueno, M.; Shinada, K.; Zaitsu, T.; Wright, F.A.; Kawaguchi, Y. Association of Hyposalivation with Oral Function, Nutrition and Oral Health in Community-Dwelling Elderly Thai. Community Dent. Health 2016, 29, 1–7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).