1. Introduction

Germ cell tumors (GCT) are the most common cancer affecting young males between 20 and 34 years of age. An estimated 1200 new cases and 35 deaths occurred in Canada in 2021 due to GCT[

1].

Although metastatic GCT is highly curable, 20-30% of patients relapse after initial cisplatin-based chemotherapy, including 40-50% of patients presenting with International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCG) poor risk disease [

2]. For these relapsed patients, salvage chemotherapy is associated with long-term cure rates of 50% [

3]. Salvage chemotherapy options include conventional-dose (CDCT) and high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT); however, treatment strategies vary in the absence of definitive comparative data, pending results from TIGER clinical trial. The TIGER trial is a randomized phase III trial of CDCT (paclitaxel, ifosfamide and cisplatin (TIP)) vs HDCT (two cycles of paclitaxel and ifosfamide followed by three cycles of high-dose carboplatin and etoposide (TI-CE)) as initial salvage chemotherapy for patients with GCT (NCT02375204) [

4]. Currently, IT-94 is the only randomized clinical trial which compared 4 cycles of CDCT (cisplatin, etoposide and ifosfamide (VIP) or vinblastine, ifosfamide and cisplatin (VeIP) (arm A) to 3 cycles of CDCT (VIP or VeIP) followed by one cycle of HDCT (carboplatin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide) with ASCT (arm B), with no significant difference in overall survival (OS) [

5]. Several methodological shortcomings make the interpretation of this trial results challenging, with the exclusion of patients who did not achieve complete response to first line chemotherapy, a significant proportion of patients (>25%) not receiving planned HDCT, and only one HDCT cycle being used.

For relapsed GCT patients requiring salvage chemotherapy, the International Prognostic Factor Study Group (IPFSG) risk stratification is prognostic and may potentially be a useful tool for treatment selection. The IPFSG criteria include primary site of disease, prior initial treatment response, progression-free interval, AFP and B-HCG level at relapse, and presence of distant metastasis such as liver, brain, and bone. Results from a large multicentered retrospective database reported by Lorch et al. suggested the superiority of HDCT over CDCT in progression free survival (PFS) and OS in each IPFSG subgroup except for low-risk patients. However inherent limitations exist due to the retrospective nature of this study [

5,

6,

7]. Other retrospective data suggests IPFSG very-low-risk and low-risk patients have similar outcomes with CDCT or HDCT [

8], although prospective studies are warranted for validation.

Given the uncertainty of the optimal curative-intent salvage chemotherapy strategy in this setting and potential for improving outcomes, we aimed to characterize the contemporary real world practice patterns of salvage chemotherapy across Canada, including treatment availability, patient selection and management strategies used for relapsed GCT patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a multicenter national survey of physicians to examine real world practice patterns of the use of salvage chemotherapy in patients with relapsed GCT. To our knowledge, no prior surveys on this topic were published in the literature at the time of study design. The survey questions were developed with multidisciplinary input and revisions from medical oncologist and hematologists who treat relapsed GCT. The survey was pilot tested to ensure the questions were clearly articulated, relevant and comprehensive. The final online survey consisted of 30 multiple choice questions (appendix A) and took approximately 7 minutes to complete. The survey was administered via Survey Monkey in August 2021, using email membership listservs of Genitourinary Medical Oncologists of Canada and Cell Therapy Transplant Canada to capture both staff medical oncologists and hematologists. Participation was voluntary with no financial incentive to complete the survey. Reminders emails were sent every 2-4 weeks after the initial email invitations, and the survey was closed in March 2022. Respondents could choose not to respond to certain questions. The survey was anonymous, no survey respondent was identified individually, and all data was reported in aggregate and confidentially. Email addresses were discarded at the conclusion of this study. Data were analyzed using quantitative methodologies and descriptive statistics. Response rates and other categorical data were reported as proportions, while continuous data were described using range. Free text responses were categorized to reveal any notable trends. All percentages were calculated as a function of the number of respondents for each question. Data from incomplete questionnaires were included for analysis whenever possible.

3. Results

The respondents included 30 physicians, 25 (83.3%) medical oncologists, 3 (10%) hematologists, 2 (6.6 %) identified as both. Responses were captured from 18 cancer centers across 8 provinces: Ontario (53.3%); Quebec (20%); Alberta, (6.6%); British Columbia, ( 3.3%); Manitoba, (6.6%); New Brunswick, (3.3%); Nova Scotia, (3.3%); and PEI, (3.3%) (

Table 1).

Most respondents (26, 86%) were from academic centers, and reported case volumes of salvage chemotherapy 5 cases or less per year (

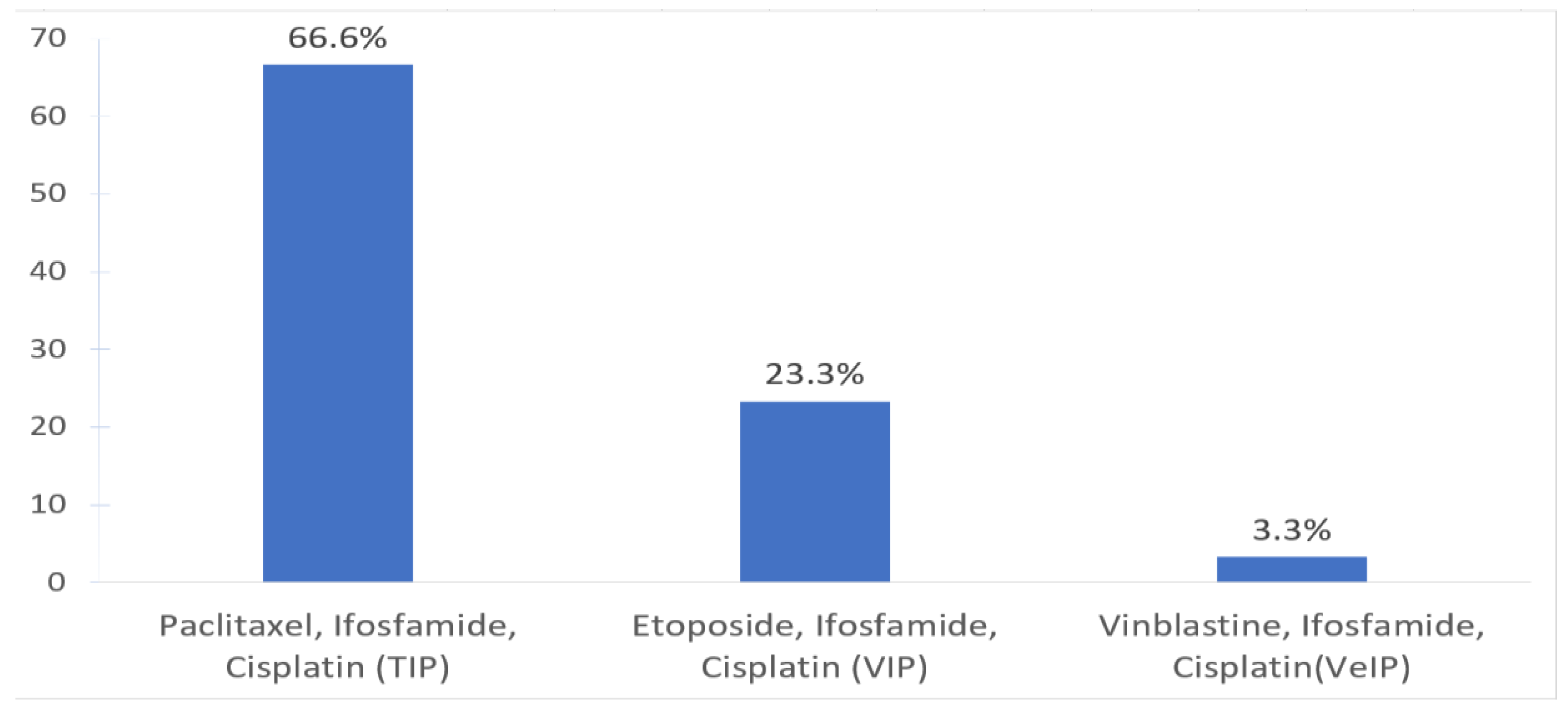

Table 1). No clinical trials are available for relapsed GCT patients requiring salvage chemotherapy during the time of this survey. The most commonly used CDCT regimen was TIP (66.6%) and VIP (23.3%) (

Figure 1).

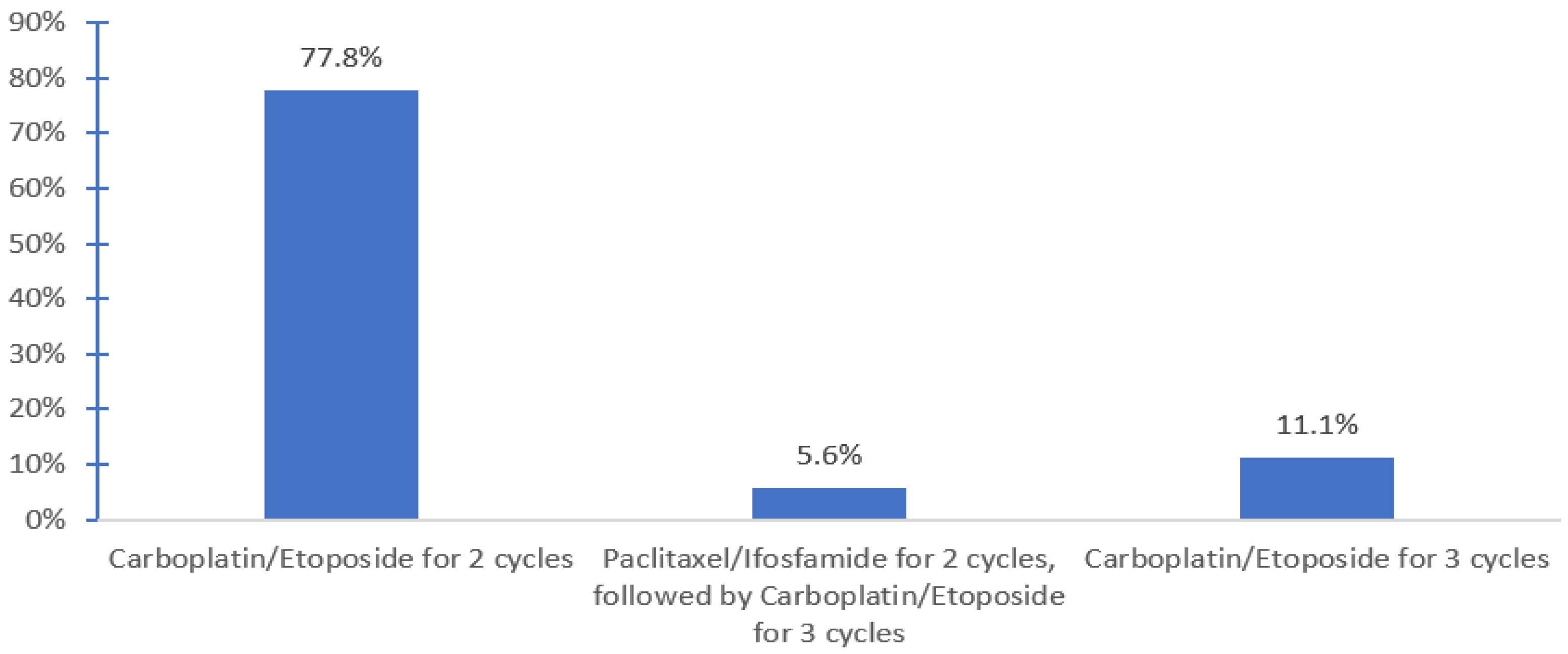

HDCT was available for 72.4% of respondents in 13 centers. HDCT regimen used included carboplatin and etoposide for 2 cycles with tandem ASCT (Indiana protocol, 77.8%) and the TICE protocol 11.1%) (

Figure 2). Planned hospital admission was required by 83.3% of the respondents who offered salvage HDCT and ASCT.

Among 20 respondents who offered HDCT and ASCT, only 25% reported HDCT can be organized within 3 weeks. Most (65.0%) required CDCT as a bridging therapy while awaiting HDCT and ASCT to be organized. Stem cells are most often collected within 4 weeks (69.2%) with a minimum target CD34 cell dose of 2-3x 106/kg (33.3%), and salvage HDCT and ASCT would begin 2-4 weeks after peripheral stem cell collection (66.6%). After completion of bridging CDCT, most (61.5%) required both tumor markers (AFP, BHCG, LDH) and radiological imaging to assess response; 69.2% of those would have patients proceed to HDCT and ASCT regardless of the biochemical and radiology response. However, 7.7% would proceed only if evidence of disease response, and 23.1% would make the decision to proceed as per case-by-case discussion (e.g one described giving another cycle of CDCT if no response). Others mentioned discussion via national email tumor board). After one cycle of HDCT, both tumor markers and radiology imaging were required to document response in 18.7% of the respondents, while 75% only required tumor markers. However, 37.5% of the respondents would proceed to the second transplant regardless of the results.

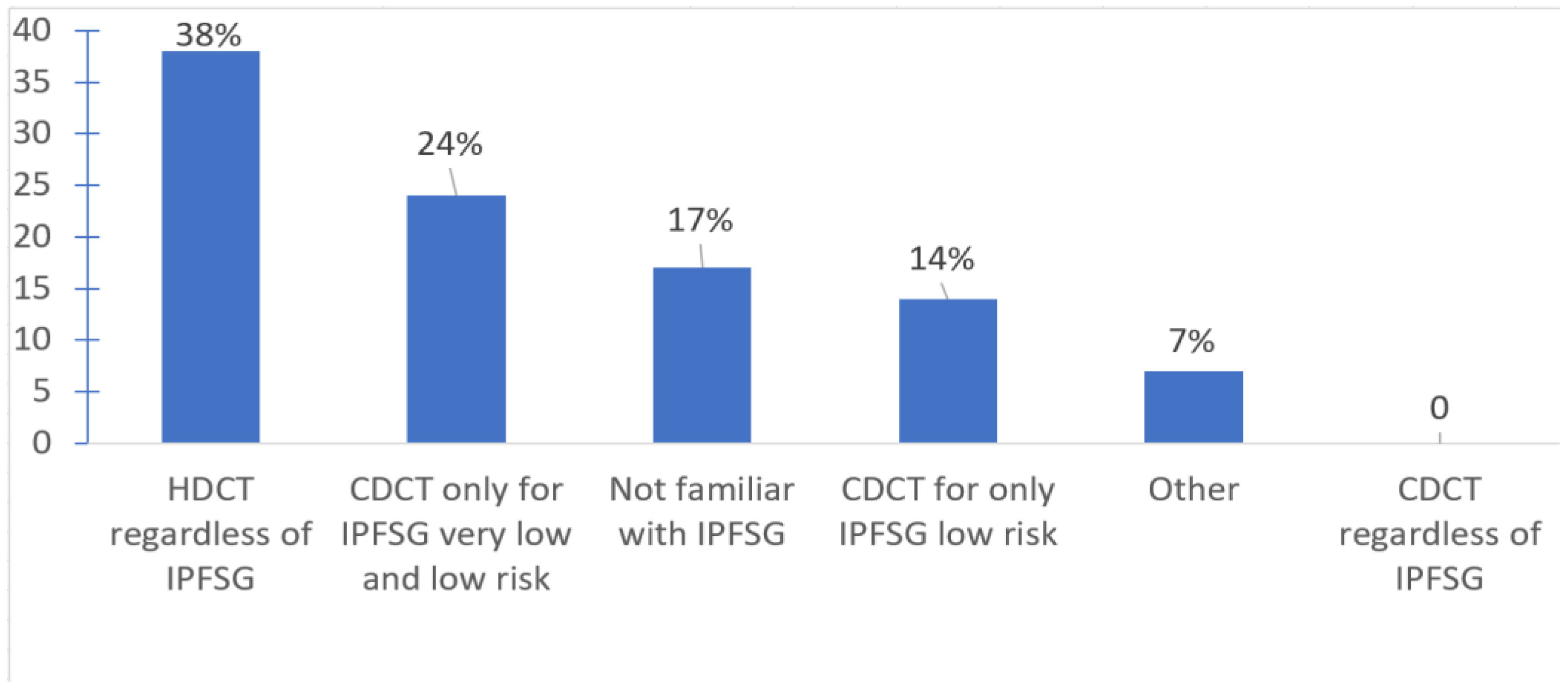

With respect to treatment selection, most offered salvage HDCT and ASCT in the first line salvage setting (75.9%); some favored second (20.7%) or third line (3.5%) settings. Only about a third of oncologists used the IPFSG criteria to determine eligibility for HDCT. IPFSG criteria did not impact treatment selection for HDCT for 37.9% (use HDCT regardless of IPFSG category); 24% of the respondents use CDCT only for very low and low risk IPFSG disease; and 14% use CDCT for only low risk IPFSG. Among the respondents, 17.2% were not familiar of the IPFSG criteria (

Figure 3).

None reported any impact of the ongoing covid-19 pandemic on the selecting salvage chemotherapy (either CDCT or HDCT) for patients with relapsed GCT.

Surveillance investigations after completion of HDCT and ASCT include tumor markers and imaging every 2-4 months in the first year (

Table 2).

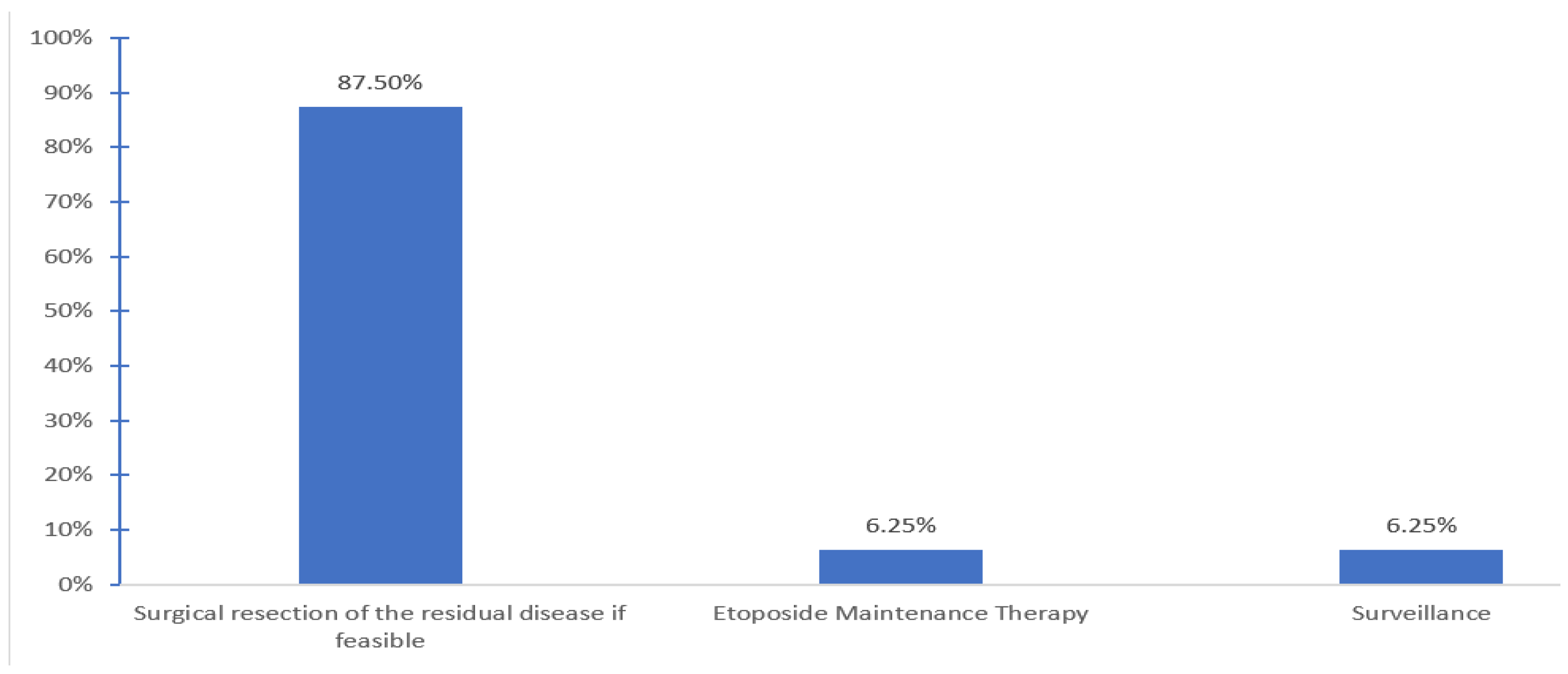

Patients are generally followed by medical oncology (56.2%) or both medical oncology and hematology (37.5%). Post salvage chemotherapy treatment options offered after completion of HDCT and ASCT include surgical resection of the residual if feasible (87.5%, 9 centers), maintenance etoposide (6.3%, one center) and none other than surveillance (6.3%, one center) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

For patients with relapsed GCT following initial cisplatin-based chemotherapy, the optimal salvage chemotherapy regimen is still being debated. According to this Canadian survey study, the use of salvage HDCT and ASCT was favored over CDCT in the first line salvage setting upon relapse following initial cisplatin-based chemotherapy, which is consistent with previous data [

9]. The IPFSG criteria was used by about a third of oncologists surveyed to select CDCT for IPFSG very low risk and/or low risk patients., and 17% surveyed were in fact not familiar with this prognostic score. Our results echo the observed variation of treatment pattern around the world. Investigators from Indiana University favor the use of HDCT as the initial salvage therapy approach[

10]. In Germany, Zschäbitz et al. published their experience in selecting HDCT as the initial salvage therapy approach in 67% of patients, including IPFSG intermediate (

n = 12, 26%), high (

n = 16, 35%), or very high risk (

n = 9, 20%) relapsed GCT [

11]. Oncologists at Memorial Sloan Kettering employ a risk stratified approach of CDCT with TIP or HDCT with the TICE protocol[

12]. In comparison, in the UK, salvage HDCT is mostly reserved for the third-line setting [

13].

Large retrospective multicentered data have suggested the potentially utility of IPFSG criteria in treatment selection [

8], which have been validated in multiple other cohorts. Available data suggests HDCT is associated with 10-15% improvement in OS rates compared to CDCT in all risk groups except IPFSG low risk disease, which awaits confirmation from the TIGER trial. This trial is aiming to compare overall survival TIP versus TI-CE regimen (1:1), stratified by IPFSG risk classification (low, intermediate, and high) (Clinical Trials.gov identifier NCT02375204). Based on our survey results, in Canada, both approaches of using CDCT in IPFSG very low or low risk groups or HDCT in all IPFSG risk groups are used and are acceptable options. The use of HDCT in the first line salvage setting may be preferable to some given it is more effective than its use in subsequent treatment settings[

14].

To note, the 2010 Canadian consensus guidelines for the management of testicular GCT indicated that either CDCT or HDCT were options in patients who relapse post cisplatin based chemotherapy and that a number of clinical and tumor related factors must be taken into account when choosing[

15]. The updated 2022 Canadian consensus guidelines do recommend risk stratifying patients based on the IPFSG risk stratification but caution that there is no prospective conclusive randomized data identifying which type of salvage treatment produces the best outcomes. It recommends that in patients with very low or low IPFSG risk either CDCT or HDCT are reasonable options, in patients with intermediate IPFSG risk group, HDCT is the preferred treatment option however there may be some circumstances where CDCT is reasonable, and for patients with high and very high IPFSG risk, HDCT is the preferred treatment option[

16].

Most commonly, salvage HDCT was administered as tandem high dose carboplatin etoposide with ASCT (Indiana protocol), which is associated with 2 years PFS and 5 years OS rates of 47-65%[

14,

17,

18,

19], however two (11%) used the TICE regimen. In most centers, bridging CDCT was required due to logistics of organizing HDCT. Whether this improves the effectiveness of salvage HDCT is unknown and requires further study. It is notable that some physicians would offer salvage HDCT only if there is disease response to CDCT. In the few cases where patients do not respond to bridging CDCT, some can still achieve cure and current data suggest they should be excluded from HDCT [

20]. On the other hand, some respondents indicated that patients will still proceed with the subsequent cycle of HDCT if disease progresses after the first cycle. To our knowledge, there is no evidence supporting this approach and it is unlikely that long-term disease control will be achieved in this situation considering the potential toxicity, cost and limited benefit. Instead, alternative strategies such as post chemo surgical resection for nonseminoma or alternative palliative chemotherapy regimens such as GemOx should be considered[

21].

The most common conventional CDCT regimens used in our survey is TIP followed by VIP. Many phase II studies support using TIP as the preferred initial salvage CDCT regimen. Complete remission rates with TIP have been reported between 31-71%. The MSKCC group have shown 2-year PFS 65% and 2-years OS 78% which represent some of the best outcomes of salvage chemotherapy with CDCT. It is important to note that this study reported on a select group of patients who had somewhat favorable disease characteristics including purely gonadal primaries and response to initial cisplatin-based chemotherapy for

6 months prior to relapse[

22,

23,

24]. Other retrospective and prospective phase II studies evaluating VIP or VeIP have shown CR rates in 19-56% which support their use as less favored but alternative options of CDCT [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

In our survey most considered surgical resection of residual disease if feasible post salvage chemotherapy (87.5%, 9 centers). This is supported by the most recent Canadian guideline recommendations[

16]. Cary et al. reported the outcomes of the post- HDCT and ASCT retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) in 92 patients treated at Indiana University. Histological findings were viable tumor (38%), necrosis (26%), and teratoma (34%). The 5-year OS of patients undergoing RPLND after HDCT was 70% in the Indiana University cohort [

31]. Miller et al. reported the surgical outcomes of 112 patients who underwent RPLND following salvage CDCT or HDCT at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Histopathological findings were viable cancer (27%), teratoma (23%) and fibrosis (50%)[

12]. Maintenance oral etoposide (50 mg po daily 21 days every 28 days) post salvage therapy is not routinely used in Canada. Retrospective data have shown potential promise for this approach [

32,

33]. However, further prospective data is needed. A randomized phase II clinical trial of maintenance oral etoposide or observation following HDCT for relapsed GCT is ongoing and pending results (NCT04804007) [

34].

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. Patients with relapsed GCT who require salvage chemotherapy are uncommon, and the low case volumes of some centers may have skewed some of the results. Centralization of care for these patients can be challenging considering the vast geography of Canada, and future efforts in standardization of practice across regions will be critical. The low response rate of hematologists limits the data on current delivery of HDCT and ASCT in Canada, however building on this survey study, differences in institutional protocols and resources for transplant in this rare treatment setting will be investigated in future studies.

5. Conclusions

HDCT was available for most academic centers in Canada and was the most commonly preferred strategy in the first-line salvage treatment setting. Two cycles of carboplatin and etoposide is the most common HDCT regimen. TIP is the most commonly used CDCT regimen. Significant differences exist in the treatment selection, delivery of HDCT, and post-salvage chemotherapy care, highlighting the need for standardization of care for patients with relapsed testicular GCT requiring salvage chemotherapy. Patients who relapse after initial chemotherapy require multidisciplinary expertise at experienced centers for optimal and timely management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Appendix A.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EA, AZ, AH and DMJ; Data curation, EA; Formal analysis, EA, AZ and DMJ; Methodology, EA, AZ and DMJ; Resources, EA, AH, RH, MC, JK, LW, LN, CK, SN, EW, DS, SH and DMJ; Software, EA, AZ and DMJ; Supervision, DMJ; Writing – original draft, EA, AZ, RH, MC, LW and DMJ; Writing – review & editing, EA, AH, RH, MC, JK, LW, LN, CK, SN, EW, DS, SH and DMJ; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was a survey study of clinicians which did not require research ethics board review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our special thanks to our colleges Dr. Carlos Stecca, Dr. Philippe Bedard and Dr. Srikala Sridhar for their insightful advice and suggestions which were especially valuable to us for this project. We thank the Meekison, Keystone and Posen families for their support for the Canadian GCT symposium.

Conflicts of Interest

RH received fund from Janssen, Abbvie, Bayer, Astellas Pharma (Honoraria); Janssen, Bayer (Research Funding); Janssen (Travel, Accommodations, Expenses). AH received funding from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Novartis AstraZeneca (Consulting or Advisory Role); and Karyopharm Therapeutics, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche/Genentech, Janssen, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Astellas Pharma, BioNTech, Pfizer/EMD Serono, Neoleukin Therapeutics (Research Funding). MC received fund from Gilead Sciences, Servier/Pfizer (Honoraria); SERVIER, Gilead Sciences, Novartis Canada Pharmaceuticals Inc (Consulting or Advisory Role); Roche Canada (Research Funding). LW received fund from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Roche Canada, Merck, AstraZeneca (Research Funding). CK received fund from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Merck KGaA, Merck, Astellas Pharma, Janssen Oncology, Eisai (Honoraria); Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, Ipsen, Eisai, Janssen, Merck KGaA, Merck, Gilead Sciences (Consulting or Advisory Role); Pfizer, Ipsen (Travel, Accommodations, Expenses). SN received fund from Janssen-Ortho, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, Merck, Roche Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb (Honoraria); Astellas Pharma, Sanofi, Pfizer, Roche Canada, Merck, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EMD Serono (Consulting or Advisory Role); Astellas Pharma, Janssen, AstraZeneca (Research Funding); AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma (Travel, Accommodations, Expenses). EW received fund from Merck, Bayer, Eisai, Amgen, Roche, Ipsen (Consulting or Advisory Role), Roche/Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, Eisai, Ayala Pharmaceuticals (Research Funding). DS received fund from Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Ipsen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Adlai Nortye (Honoraria); Merck, Pfizer, Ipsen, Adlai Nortye(Consulting or Advisory Role); Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Roche/Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Adlai Nortye(Research Funding). SH received fund Astellas Scientific and Medical Affairs Inc, Janssen Oncology, Bayer, Merck Ipsen, Eisai (Honoraria); Janssen, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Bayer AstraZeneca, Merck, Eisai, Ipsen, Advanced Accelerator Applications Seattle Genetics (Consulting or Advisory Role); Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers SquibbSeattle Genetics, SignalChem (Research Funding); Eisai, (Travel, Accommodations, Expenses). DMJ received fund from Janssen Oncology, Ipsen, Bayer, EMD Serono (Honoraria); Bayer (Consulting or Advisory Role). All other authors have no COI.

References

- Committee CCSA, S.C. , Canada S, et al. . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2021.

- Abughanimeh, O.; Teply, B.A. Current Management of Refractory Germ Cell Tumors. Curr Oncol Rep 2021, 23, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oing, C.; Lorch, A. The Role of Salvage High-Dose Chemotherapy in Relapsed Male Germ Cell Tumors. Oncol Res Treat 2018, 41, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A. Management of Refractory Germ Cell Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018, 38, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pico, J.-L.; Rosti, G.; Kramar, A.; Wandt, H.; Koza, V.; Salvioni, R.; Theodore, C.; Lelli, G.; Siegert, W.; Horwich, A. A randomised trial of high-dose chemotherapy in the salvage treatment of patients failing first-line platinum chemotherapy for advanced germ cell tumours. Ann Oncol 2005, 16, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A.; Kleinhans, A.; Kramar, A.; Kollmannsberger, C.K.; Hartmann, J.T.; Bokemeyer, C.; Rick, O.; Beyer, J. Sequential Versus Single High-Dose Chemotherapy in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Germ Cell Tumors: Long-Term Results of a Prospective Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, J.; Stenning, S.; Gerl, A.; Fossa, S.; Siegert, W. High-dose versus conventional-dose chemotherapy asfirst-salvage treatment in patients with non-seminomatousgerm-cell tumors: a matched-pair analysis. Ann Oncol 2002, 13, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A.; Beyer, J.; Bascoul-Mollevi, C.; Kramar, A.; Einhorn, L.H.; Necchi, A.; Massard, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Fléchon, A.; Margolin, K.A.; et al. Prognostic factors in patients with metastatic germ cell tumors who experienced treatment failure with cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 4906–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seftel, M.D.; Paulson, K.; Doocey, R.; Song, K.; Czaykowski, P.; Coppin, C.; Forrest, D.; Hogge, D.; Kollmansberger, C.; Smith, C.A.; et al. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing auto-SCT for advanced germ cell tumour: a multicentre cohort study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011, 46, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashdan, S.; Einhorn, L.H. Salvage Therapy for Patients With Germ Cell Tumor. J Oncol Pract 2016, 12, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschäbitz, S.; Distler, F.A.; Krieger, B.; Wuchter, P.; Schäfer-Eckart, K.; Jenzer, M.; Hohenfellner, M.; Dreger, P.; Haag, G.M.; Jäger, D.; et al. Survival outcomes of patients with germ cell tumors treated with high-dose chemotherapy for refractory or relapsing disease. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 22537–22545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.I.; Feifer, A.; Feldman, D.R.; Carver, B.S.; Bosl, G.J.; Motzer, R.J.; Bajorin, D.F.; Sheinfeld, J. Surgical Management of Patients with Advanced Germ Cell Tumors Following Salvage Chemotherapy: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Experience. Urology 2019, 124, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamash, J.; Ansell, W.; Alifrangis, C.; Thomas, B.; Wilson, P.; Stoneham, S.; Mazhar, D.; Warren, A.; Barrett, T.; Alexander, S.; et al. The impact of a supranetwork multidisciplinary team (SMDT) on decision-making in testicular cancers: a 10-year overview of the Anglian Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (AGCCCG). Br J Cancer 2021, 124, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, L.H.; Williams, S.D.; Chamness, A.; Brames, M.J.; Perkins, S.M.; Abonour, R. High-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue for metastatic germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Jewett, M.; Chung, P.; Hotte, S.; O’Malley, M.; Sweet, J.; Anson-Cartwright, L.; Winquist, E.; North, S.; et al. Canadian consensus guidelines for the management of testicular germ cell cancer. Can Urol Assoc J 2010, 4, e19–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, R.J.; Canil, C.; Shrem, N.S.; Kuhathaas, K.; Jiang, M.D.; Chung, P.; North, S.; Czaykowski, P.; Hotte, S.; Winquist, E.; et al. Canadian Urological Association consensus guideline: Management of testicular germ cell cancer. Can Urol Assoc J 2022, 16, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.R.; Sheinfeld, J.; Bajorin, D.F.; Fischer, P.; Turkula, S.; Ishill, N.; Patil, S.; Bains, M.; Reich, L.M.; Bosl, G.J.; et al. TI-CE High-Dose Chemotherapy for Patients With Previously Treated Germ Cell Tumors: Results and Prognostic Factor Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adra, N.; Abonour, R.; Althouse, S.K.; Albany, C.; Hanna, N.H.; Einhorn, L.H. High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Peripheral-Blood Stem-Cell Transplantation for Relapsed Metastatic Germ Cell Tumors: The Indiana University Experience. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A.; Kleinhans, A.; Kramar, A.; Kollmannsberger, C.K.; Hartmann, J.T.; Bokemeyer, C.; Rick, O.; Beyer, J. Sequential versus single high-dose chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory germ cell tumors: long-term results of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, A.; Neubauer, A.; Hackenthal, M.; Dieing, A.; Hartmann, J.T.; Rick, O.; Bokemeyer, C.; Beyer, J. High-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) as second-salvage treatment in patients with multiple relapsed or refractory germ-cell tumors. Ann Oncol 2010, 21, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pectasides, D.; Pectasides, M.; Farmakis, D.; Aravantinos, G.; Nikolaou, M.; Koumpou, M.; Gaglia, A.; Kostopoulou, V.; Mylonakis, N.; Skarlos, D. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in patients with cisplatin-refractory germ cell tumors: a phase II study. Ann Oncol 2004, 15, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondagunta, G.V.; Bacik, J.; Donadio, A.; Bajorin, D.; Marion, S.; Sheinfeld, J.; Bosl, G.J.; Motzer, R.J. Combination of paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin is an effective second-line therapy for patients with relapsed testicular germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23, 6549–6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, G.M.; Cullen, M.H.; Huddart, R.; Harper, P.; Rustin, G.J.; Cook, P.A.; Stenning, S.P.; Mason, M. A phase II trial of TIP (paclitaxel, ifosfamide and cisplatin) given as second-line (post-BEP) salvage chemotherapy for patients with metastatic germ cell cancer: a medical research council trial. Br J Cancer 2005, 93, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardiak, J.; Sálek, T.; Sycová-Milá, Z.; Obertová, J.; Hlavatá, Z.; Mego, M.; Recková, M.; Koza, I. Paclitaxel plus ifosfamide and cisplatin in second-line treatment of germ cell tumors: a phase II study. Neoplasma 2005, 52, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pizzocaro, G.; Salvioni, R.; Piva, L.; Faustini, M.; Nicolai, N.; Gianni, L. Modified cisplatin, etoposide (or vinblastine) and ifosfamide salvage therapy for male germ-cell tumors. Long-term results. Ann Oncol 1992, 3, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, J.A.; Mazumdar, M.; Bajorin, D.F.; Bosl, G.J.; Vlamis, V.; Motzer, R.J. Ifosfamide- and cisplatin-containing chemotherapy as first-line salvage therapy in germ cell tumors: response and survival. J Clin Oncol 1997, 15, 2559–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehrer, P.J., Sr.; Gonin, R.; Nichols, C.R.; Weathers, T.; Einhorn, L.H. Vinblastine plus ifosfamide plus cisplatin as initial salvage therapy in recurrent germ cell tumor. J Clin Oncol 1998, 16, 2500–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Cooper, K.; Geller, N.L.; Bajorin, D.F.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Herr, H.; Morse, M.; Fair, W.; Sogani, P.; Russo, P.; et al. The role of ifosfamide plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy as salvage therapy for patients with refractory germ cell tumors. Cancer 1990, 66, 2476–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehrer, P.J., Sr.; Einhorn, L.H.; Williams, S.D. VP-16 plus ifosfamide plus cisplatin as salvage therapy in refractory germ cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 1986, 4, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, F.; Culine, S.; Théodore, C.; Békradda, M.; Terrier-Lacombe, M.J.; Droz, J.P. Cisplatin and ifosfamide with either vinblastine or etoposide as salvage therapy for refractory or relapsing germ cell tumor patients: the Institut Gustave Roussy experience. Cancer 1996, 77, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cary, C.; Pedrosa, J.A.; Jacob, J.; Beck, S.D.; Rice, K.R.; Einhorn, L.H.; Foster, R.S. Outcomes of postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection following high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell transplantation. Cancer 2015, 121, 4369–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.A.; Einhorn, L.H. Maintenance chemotherapy with daily oral etoposide following salvage therapy in patients with germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 1995, 13, 1167–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taza, F.; Abonour, R.; Zaid, M.A.; Althouse, S.K.; Anouti, B.; Akel, R.; Hanna, N.H.; Adra, N.; Einhorn, L.H. Maintenance Oral Etoposide After High-Dose Chemotherapy (HDCT) for Patients With Relapsed Metastatic Germ-Cell Tumors (mGCT). Clin Genitourin Cancer 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashkar, R.; Adra, N.; Abonour, R.; Zaid, M.I.A.; Snow, C.I.; Hanna, N.H.; Einhorn, L.H. Randomized phase 2 trial of maintenance oral etoposide or observation following high-dose chemotherapy for relapsed metastatic germ cell tumor. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, TPS429–TPS429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).