Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

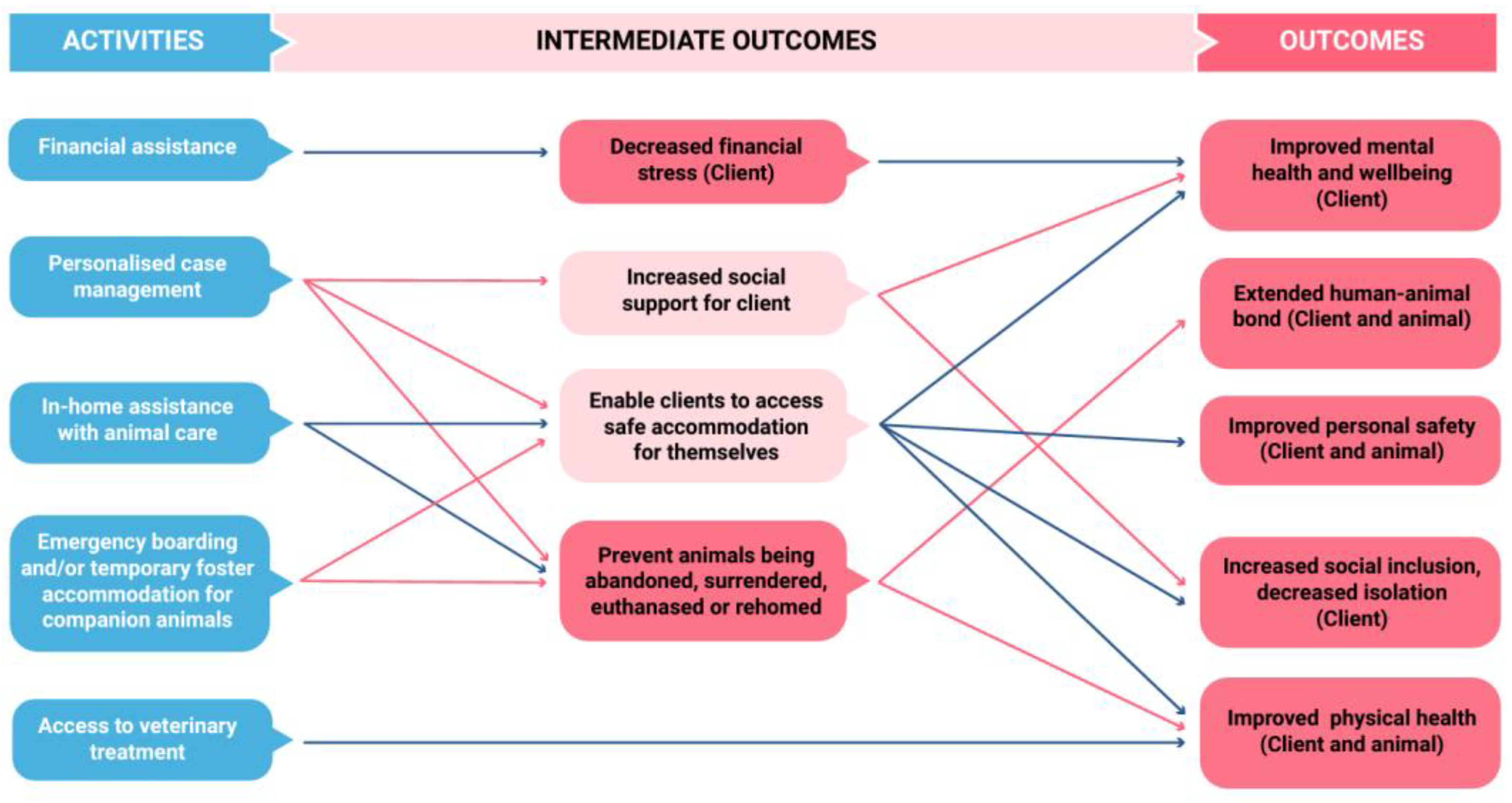

2.1. The RSPCA NSW Emergency Boarding & Homelessness Program

2.3. Identifying stakeholders

2.4. Stakeholder engagement

2.4.1. Interviews

2.4.2. Questionnaires

2.5. Analysis and modelling

3. Results

3.1. Evidencing outcomes

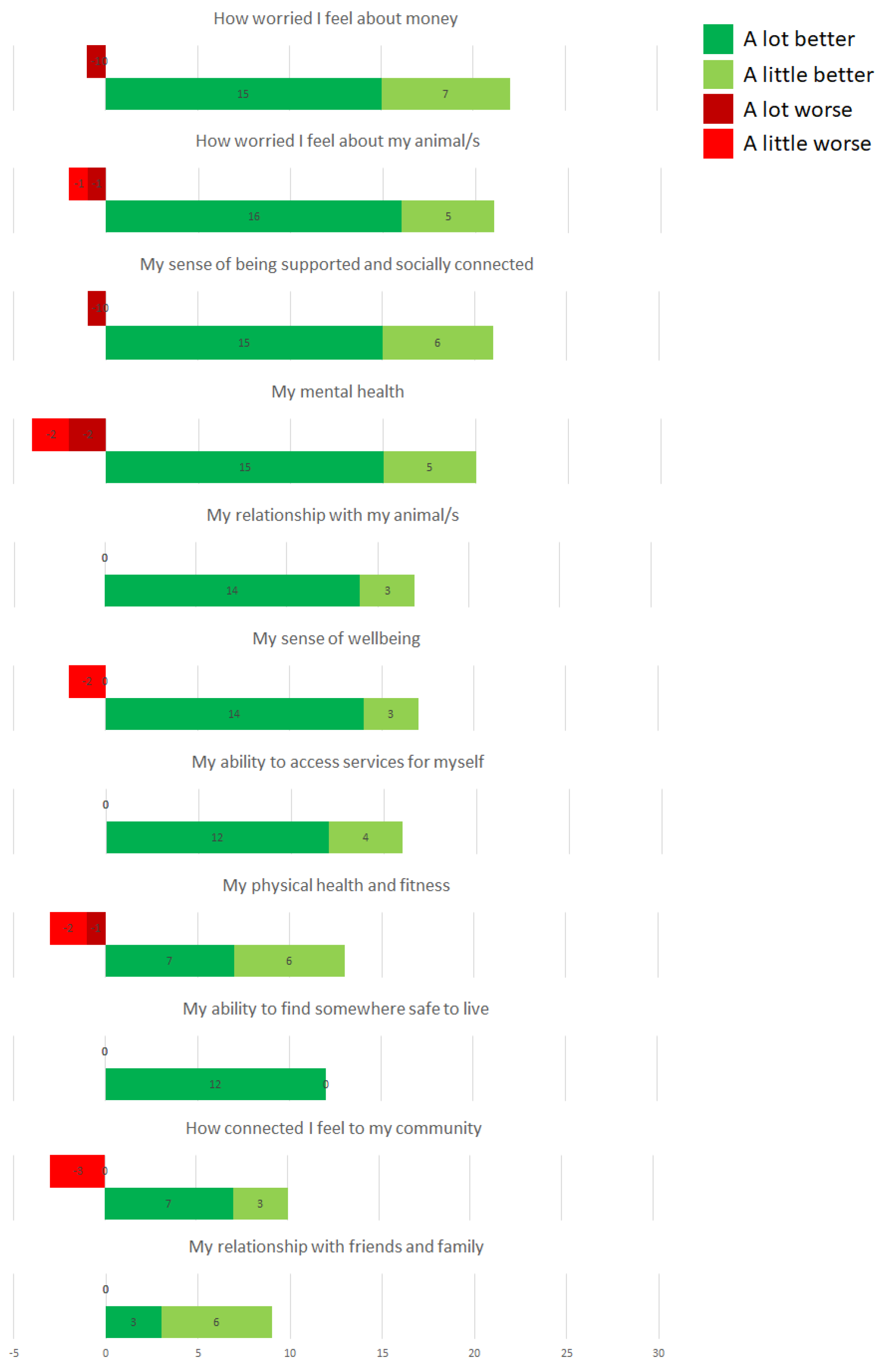

3.1.1. Outcomes experienced by clients

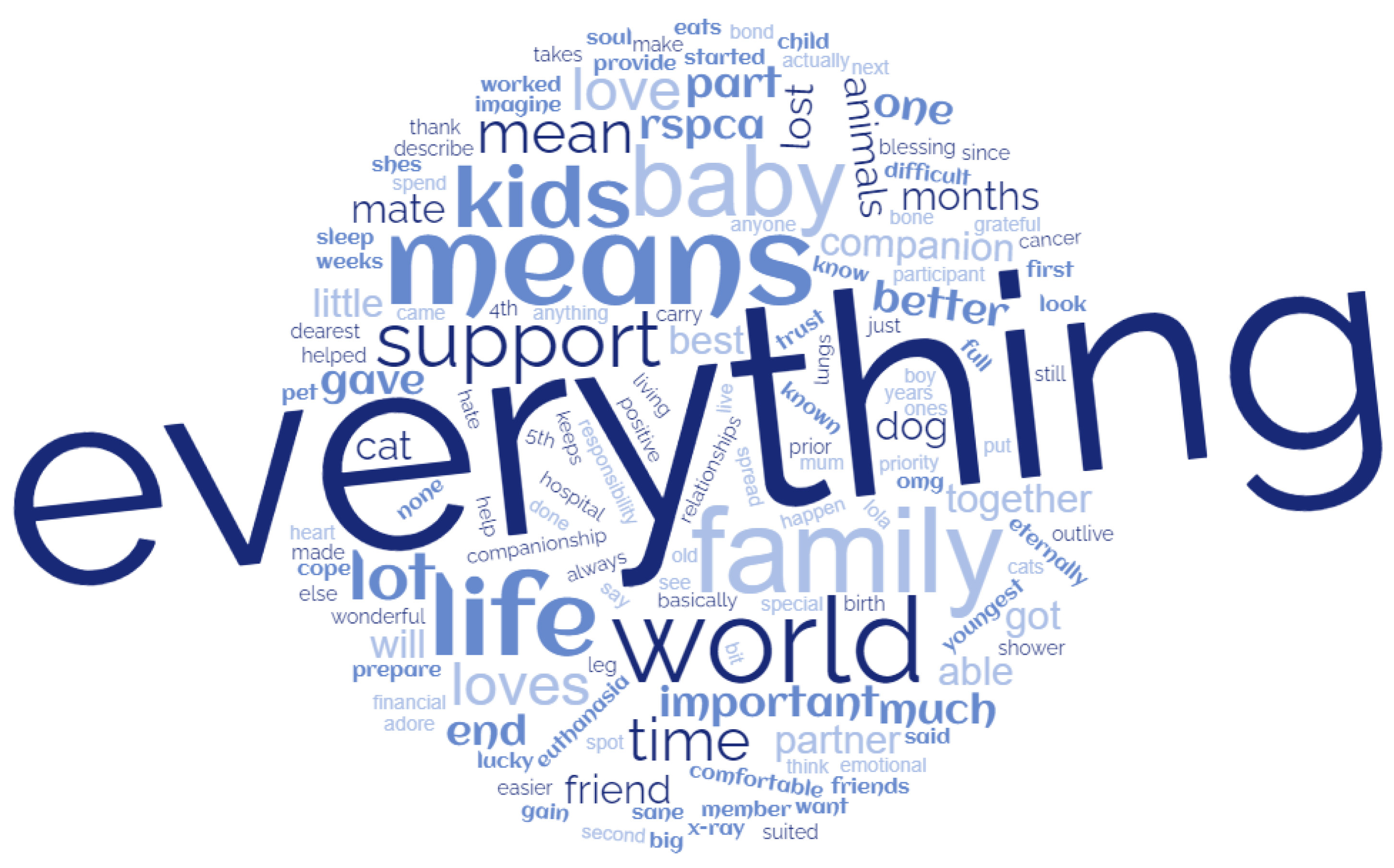

“That I got to be able to still have my cat because there are times in my life where my cat has saved me [from suicide].” Stacy – program client

“[My cats] are the reason I feel carpet under my feet in the morning. Over the years my life got to the point where I’ve lost so much, and not just material stuff and money, but all the other shit that goes with it, and they were my anchor. They made me come home every night. Be there to feed them by 6 o’clock every. Single. Day. I’m up every single morning to put food in their bowls. Their bowls are washed out religiously. These are the things I’ve got to do every day. That’s what the cats mean to me. They basically took the place of an antidepressant.

“When you’re in the situation I was in – a crisis situation – you’re not connected to anything. You’re quite alone and even though there were services around me the cats kept me focused on what I needed to do. Do you know what I mean? It wasn’t all lost. The girls were coming with me and that made it sort of better. [When I knew the cats were safe] it was just like “I’m good now. I can do anything.” It was just really, really important that I had them there and I knew that they were coming back. Yep 100%, that was just everything.” Amber – program client

“He means everything to me. He is my life. He is the only one that I have in my life. He keeps me sane. I don’t know what I would do or where I would be without him. He is very special to me. He’s not just a pet, he is my companion and my support. He is my everything. I cannot see myself living without him. I am one of the lucky ones to have a dog.” Kimberly – program client

“[Without RSPCA] it would be a lot different. My life would be a little bit empty without them because I’ve spent the last 10 years looking after them. My life would feel empty without them. Like if you have animals and cats in your life and then all of a sudden you don't have them, because you had an accident and went to hospital, and the cats get re-homed, you know that would be a devastating thing to go through. I would miss them terribly. And even small jobs like cleaning the kitty litter and stuff like that. There’s nothing that can replace the happiness having a cat can bring you. I’d hate it and the animals wouldn’t like it either.” Scott – program client

“[The most valuable thing was] knowing there is help out there, as I am a single mum and do not have a job, so I could not afford the vet treatment. I would have been forced to surrender her, but because of RSPCA’s help we could stay together as a family and I am so grateful to be able to pay this off, it means everything to me. RSPCA will never know how much I appreciate what they have done for us.” Diana – program client

| Outcome | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Extended or enhanced human-animal bond | 93% |

| Improved mental health and wellbeing | 90% |

| Increased social inclusion/decreased isolation | 72% |

| Decreased financial stress | 76% |

| Improved access to care for themselves | 59% |

| Improved personal safety | 41% |

| Improved physical health | 38% |

3.1.2. Outcomes experienced by clients’ animals

“For the first time I had some actual choices. When you are in crisis, your animal’s welfare is so at risk.” Jennifer – program client

“[Without RSPCA] it would have been the end of my dog as I would have had to have her euthanized.” Brian – program client

“[Without RSPCA] my kids would have been heartbroken as we would have had to surrender her.” Diana – program client

3.1.3. Outcomes experienced by RSPCA NSW Inspectors

“It's a huge relief to have programs available to assist. If I had more cases that programs couldn’t assist with, I’d feel stressed, and it would be quite difficult. I can go home and sleep at night and not worry that I left the dog in an environment that wasn't ideal and there's no monitoring. Or I'm going to have to take someone through a court system for something that I know ahead of time, it's going to go under the Mental Health Act. You have to question why you're taking that route in the first place. But if there are significant animal welfare issues and you can't leave the animal, you've got no other choice. I mean, I would hate to be plagued with that on my mind because my mental health will start to be affected and I’d probably end up needing assistance myself.” RSPCA Inspector

3.1.4. Outcomes experienced by animal pounds and shelters

“They would've taken my dog away from me if I couldn't find help.” Nathan – program client

“I was very stressed at the time and financially strained. [Without RSPCA] I would have had to surrender my animals.” Angela – program client

3.1.4. Unintended and negative outcomes

3.2. Valuing outcomes

3.3. The counterfactual

3.3.1. Deadweight

“I would have found a friend to look after him.” Jason – program client

“I would have been forced to find the money for private boarding services.” Angela – program client

3.3.2. Attribution

“No. No, I don’t know anybody.” Robert – program client

“I got online so you know like 12 months through the whole disaster, the drug raids and bloody jail and everything like that. And the cheapest thing I could find was over in [a distant suburb] and it was like $450 a week… for 5 cats per week was around 700 bucks.” Amber – program client

3.3.3. Displacement

3.4. Benefit period and drop-off

3.5. Program inputs

3.6. The social return on investment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A – Semi-structured interview guides

A.1. Interview guide - clients

- What companion animals do you care for, and what do they mean to you?

- Can you tell me a bit about life before [ANIMAL] came to RSPCA?

- What is life like now?

- What difference has RSPCA made for you? For your animal/s? For anyone else (e.g. children)

- What is the biggest difference in your life now?

- What value could you put on this change? (asked for a stated preference)

- Have you received support from other agencies/people?

- How much of this difference in your life is due to RSPCA? Can you estimate a %? (Attribution)

- What would have happened if it weren’t for RSPCA? (Deadweight) For you? For your animal? For anyone else?

- Are you aware of other organisations offering a similar service to the RSPCA program?

A.2. Interview guide – RSPCA NSW Inspectors

- Can you tell me a bit about your current role?

- What have been your experiences with RSPCA Community Programs? How does your work intersect with the work of the Programs team?

- What change have you experienced as a result of RSPCA’s Community Programs? For you and your work? For others?

- What would happen if RSPCA Community Programs did not provide the services they currently provide? For you and your work? For anyone else?

- Are you aware of other similar services to RPSCA’s Community Programs?

A.3. Interview guide – external stakeholders

- Can you tell me a bit about your current role?

- What is your connection with RSPCA’s Community Programs?

- What sort of clients do you work with? What sort of situations/difficulty are they experiencing?

- What change have you experienced as a result of RSPCA’s Community Programs? For you and your work? For others?

- What difference has RSPCA made for you? For your clients?

- What would happen if RSPCA Community Programs did not provide the services they currently provide? For you and your work? For anyone else?

- Are you aware of other similar services to RPSCA’s Community Programs?

Appendix B – Client questionnaire

- I was not allowed pets where I was living

- My pet was preventing me from finding somewhere safe to live

- Where I was living was not safe for my pet

- I needed help with my animals while I was in hospital

- I needed help with my animals while I accessed services for myself (e.g. drug and alcohol, mental health, physical rehabilitation, respite, other)

- I needed help accessing veterinary treatment

- Other, please describe

- Emergency boarding

- Veterinary treatment

- Transport

- Other, please describe

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- more than 3

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- more than 3

- Kept with you at home

- Stayed with friends/family

- Left at home alone

- Stayed at private pet boarding facility

- Rehomed

- Surrendered to a shelter or pound

- Euthanased

- Other, please describe

- My ability to find somewhere safe to live

- My ability to access services for myself (e.g. drug and alcohol, mental health, physical rehabilitation, respite, other)

- My sense of wellbeing

- My sense of being supported and socially connected

- How worried I feel about money

- How worried I am about my animal/s (e.g. their safety, health and/or wellbeing)

- How connected I feel to my community

- My physical health

- My mental health

- My relationship with my animal/s

- My relationships with friends and family

References

- Animal Medicines Australia. 2021. Pets and the pandemic: a social research snapshot of pets and people in the COVID-19 era. Available online: https://animalmedicinesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AMAU005-PATP-Report21_v1.41_WEB.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2021. Homelessness and homelessness services; Canberra.

- Davies, A.; Wood, L.J. Homeless health care: Meeting the challenges of providing primary care. Medical Journal of Australia 2018, 209, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, M.; West, S.; Visentin, D.; Phipps, M.; Westman, M.; Vesk, K.; Kornhaber, R. The unbreakable bond: The mental health benefits and challenges of pet ownership for people experiencing homelessness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2021, 42, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.; Easterbrook, M.J. The perceived costs and benefits of pet ownership for homeless people in the UK: Practical costs, psychological benefits and vulnerability. Journal of Poverty 2018, 22, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, K.; Buetow, S. Making the invisible visible: A photovoice exploration of homeless women’s health and lives in central Auckland. Social Science & Medicine 2011, 72, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022. Mental health services in Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/overnight-admitted-mental-health-related-care (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Health of people experiencing homelessness; AIHW: Canberra, 2021b.

- McCosker, L.; Downes, M.J.; Maujean, A.; Hill, N. Services and interventions for people who are homeless with companion animals (pets). Social Science Protocols 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hageman, T.; Langenderfer-Magruder, L.; Geene, T.; Williams, J.; St Mary, J.; McDonald, S.; Ascione, F. Intimate partner violence survivors and pets: Exploring practitioners’ experiences in addressing client needs. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 2018, 99, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, K.; Haase, B.; Ravulo, J.; Lomax, S.; Ma, G. The Role of Human–Animal Bonds for People Experiencing Crisis Situations. Animals 2023, 13, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, L.M. Historical perspectives on the Human-Animal Bond. American Behavioral Scientist 2003, 47, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Value International. 2012. A guide to social return on investment. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60dc51e3c58aef413ae5c975/t/60f7fa286b9c6a47815bc3b2/1626864196998/The-SROI-Guide-2012.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Australian Government. 2021. Practice Regulation Guidance Note: Value of statistical life. Available online: https://obpr.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-09/value-of-statistical-life-guidance-note-2020-08.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Australian Government. 2008. The Health of Nations: The Value of a Statistical Life. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/the-healthofnations_value_statisticallife_2008_pdf.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Inoue, M.; Kwan, N.C.; Sugiura, K. Estimating the life expectancy of companion dogs in Japan using pet cem-etery data. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2018, 17–0384. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.; Haeder, S.; Jenkins-Smith, H.; Ripberger, J.; Silva, C.; Weimer, D. Monetizing bowser: A contingent valuation of the statistical value of dog life. Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 2019, 11, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABS. 2017. Household Expenditure Survey, Australia: Summary of Results. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/finance/household-expenditure-survey-australia-summary-results/latest-release#income-and-spending (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- NDIA. 2022. Pricing Arrangements and Price Limits 2022-23 https://www.ndis.gov.au/media/4518/download?attachment.

- Canstar. 2021. What does the average Australian spend at the gym? Available online: https://www.canstarblue.com.au/health-beauty/average-gym-cost/#:~:text=Aussies%20spend%20an%20average%20of,lowest%20gym%20costs%20(%2454) (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- NSW Government. 2021. Rent Report. Available online: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/facs.statistics/viz/Rentandsales_15565127794310/Rent (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Choosi. 2022. Compare pet insurance. Available online: https://www.choosi.com.au/pet-insurance (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- APS. 2018. APS National Schedule of Recommended Fees. Available online: https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/af30b47d-ef39-49c2-8116-6d20ed1dc828/18aps-2018-19-aps-is-srf-p1-a.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Walsh, F. Human-animal bonds I: The relational significance of companion animals. Family process 2009, 48, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkow, P. Chapter 5 - Animal Therapy on the Community Level: The Impact of Pets on Social Capital. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy (Fourth Edition), Fine, A.H., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2015; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bulsara, M.; Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bosch, D. More Than a Furry Companion: The Ripple Effect of Companion Animals on Neighborhood Interactions and Sense of Community. Society & Animals 2007, 15, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. The State of Research on Human–Animal Relations: Implications for Human Health. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, A.; Amerio, A.; Odone, A.; Baertschi, M.; Richard-Lepouriel, H.; Weber, K.; Di Marco, S.; Prelati, M.; Aguglia, A.; Escelsior, A.; Serafini, G. Suicide prevention from a public health perspective. What makes life meaningful? The opinion of some suicidal patients. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91 Suppl 3, 128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Ravulo, J.; McGeown, U. Refuge for Rover: A Social Return on Investment of a program assisting victim-survivors of domestic and family violence with their pets. Social Work, 2023; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, A.L.; Salemonsen, E.; Severinsson, E. Suicide prevention strategies for older persons—An integrative review of empirical and theoretical papers. Nursing open 2021, 8, 2175–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiman, EM; Liu, RT. Social support as a protective factor in suicide: Findings from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Disord. 2013, 150, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakimi, N.; Greer, A.; Butler, A. Too Many Hats? The Role of Police Officers in Drug Enforcement and the Community, Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2022, paab082. [CrossRef]

- Balfour, M.E.; Hahn Stephenson, A.; Delany-Brumsey, A.; Winsky, J.; Goldman, M.L. Cops, clinicians, or both? collaborative approaches to responding to behavioral health emergencies. Psychiatric Services 2022, 73, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papazoglou, K.; Chopko, B. The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: An unexplored topic. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 8, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.; Ray, M. No pets allowed? Companion animals, older people and residential care. Medical humanities 2019, 45, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Funston, L.; Farrugia, C.; Coorey, L.; Verco, J.; Campbell, J. (2020). There’s More to the Story: Report on the NSW Health Education Centre Against Violence Roundtable on Animal Abuse and Domestic and Family Violence. Parramatta: NSW Health Education Centre Against Violence.

- Hardesty, J.L.; Khaw, L.; Ridgway, M.D.; Weber, C.; Miles, T. Coercive control and abused Women’s decisions about their pets when seeking shelter. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2013, 28, 2617–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volant, A.M.; Johnson, J.A.; Gullone, E.; Coleman, G.J. The Relationship Between Domestic Violence and Animal Abuse: An Australian Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2008, 23, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L. (2018). Your patient hurts, my patients hurt. Domestic & Family violence, A veterinary perspective. Unpublished presentation, NSW Health Education Centre Against Violence, Roundtable: Exploring the Intersection between Animal Abuse, Domestic & Family violence, Abuse of Children, Older persons and People with Disabilities: Indications and Opportunities, Sydney, 14 August.

- Levine, G.; Allen, K.; Braun, L.; Christian, H.; Friedmann, E.; Taubert, K.; Thomas, S.; Wells, D.; Lange, R. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk. Circulation 2013, 127, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stakeholder | Included | Reason for inclusion/exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Program clients | Yes | Group expected to directly benefit the most from the activity |

| Companion animals of clients | Yes | Benefit directly from program activities |

| RSPCA NSW Inspectorate | Yes | Clients case-managed through the RSPCA NSW Domestic Violence program are often diverted from being managed through the RSPCA Inspectorate |

| Animal pounds and shelters | Yes | Animals accessing services through the Emergency Boarding program are less likely to be surrendered to animal pounds and shelters |

| Broader community | No | Changes not material |

| Family and friends of clients | No | Changes not material |

| Other service providers | No | Changes not material |

| NSW Health | No | Improved physical health and fitness experienced by program clients might have resulted in less health expenditure. Changes experienced by NSW Health are likely to be material but were beyond the scope of this project to quantify. |

| Court system | No | Clients referred to the RSPCA NSW Emergency Boarding and Homelessness program via the RSPCA Inspectorate might otherwise be subject to prosecutions for animal cruelty or neglect under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1979 (NSW). Changes experienced by the NSW Court system are likely to be material but were beyond the scope of this project to quantify. |

| Outcome | Incidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Improved wellbeing as a result of preserving or improving the human-animal bond | 91% | |

| Improved physical health | 71% | |

| Access to safe accommodation | 71% |

| Outcome | Incidence |

|---|---|

| More time available to pursue genuine animal cruelty offenses | 80% |

| Improved mental health | 80% |

| Outcome | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Fewer animals abandoned | 9% |

| Fewer animals surrendered | 37% |

| Outcome | Proxy Description | Rationale | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved mental health and wellbeing | Contingent valuation. The value of a statistical life year ($222,000) adjusted for the loss attributable to generalised anxiety disorder – mild to moderate (disability weighting 0.17). Benefit applied for the average length of time an Emergency Boarding client's animal/s were in care (51 days). |

Clients’ companion animals provide an important source of comfort and companionship that is a consistent presence in their day-to-day life. Participation in the program enables clients to preserve this relationship, which profoundly improves wellbeing and was considered the most valuable change by clients. Hence, we equate this outcome with relieving mild anxiety. | $5,320 | Value of a statistical life year: Australian Government, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet [14] Disability weight: Australian Government, Australian Safety and Compensation Council [15] |

| Extended or enhanced human-animal bond | Contingent valuation. The value of a dog life year for a companion dog with a receptive owner, applied for the difference between the average age of an Emergency Boarding program dog (5 years) and a dog’s average life expectancy (13 years) [16]. Based on a value of $2,400 USD in 2019, converted to present value Australian dollars. |

Clients described the depth of the bond they have with their companion animals; a bond that in many cases had been strengthened by their shared experiences of trauma. Their relationship with their companion animal was often their most valuable, even their only relationship. They also described the impact that losing this bond would have on their wellbeing. | $3,453 | Carlson et al, 2019 [17] |

| Decreased financial stress | Observed spending on related goods. The difference in cost between the emergency boarding rate charged to RSPCA NSW Community Programs clients ($10/day) and the cost of boarding through a private pet boarding facility ($50/day) for the average duration an Emergency Boarding client’s animal/s were in care (51 days). |

Clients experiencing this outcome avoid incurring upfront costs associated with providing safe temporary accommodation for their animals through private boarding facilities. Clients also receive discounted pet boarding through the program. In interviews clients reported the alternative to accessing the RSPCA program would be to pay for pet boarding through a private boarding facility or veterinary hospital and that this would typically cost around $50/day. |

$2,058 | Client interviews |

| Increased social inclusion/decreased isolation | Time use method. The average amount spent on recreation for six months. Based on the average weekly income for a one-parent family of $1,187, and the proportion of weekly income spent on recreation for families in the lowest income bracket (9%). |

According to clients, participation in the Emergency Boarding program increased their social inclusion and decreased their social isolation including increasing their sense of being supported and connected to their community and improved relationships with family and friends. Hence, we use the amount spent on recreation as a proxy to represent improved social interactions and social connectedness. |

$2,778 | Australian Bureau of Statistics [18] |

| Improved access to care for themselves | Observed spending on related goods. The cost of an allied health assistant ($56.16/hour) for one hour once per week for the average duration an Emergency Boarding client’s animal/s were in care (51 days). |

Clients reported in interviews and questionnaire responses that the assistance provided by RSPCA enabled them to better access care and services for themselves, for example attending hospital, accessing mental health and rehabilitation services. We consider a weekly session with an allied health assistant would provide similar benefits. Allied health assistants facilitate functional improvement and provide supports aimed at adjustments, adaptation, and building capacity for clients. |

$413 | National Disability Insurance Agency [19] |

| Improved physical health | Observed spending on related goods. The typical cost of an annual gym membership. |

Some clients reported experiencing improved physical health as a result of their participation in the RSPCA Emergency Boarding program. We determined that an annual gym membership would provide similar benefits to clients experiencing this outcome. |

$1,140 | Canstar Blue [20] |

| Improved personal safety | Observed spending on related goods. The cost of secure accommodation based on the median weekly rent for NSW 2020-21 of $466.25 per week for the average length of time Emergency Boarding client's animal/s were in boarding or foster care (51 days). |

Clients were better able to seek safety for themselves as a result of having somewhere safe to place their animals. In the context of people experiencing homelessness or medical or mental health crises, finding secure accommodation would be expected to provide a similar outcome for clients. Hence the median weekly rent in NSW for the duration client’s animal/s were in care has been used as a proxy. | $3,427 | NSW Government [21] |

| Outcome | Proxy Description | Rationale | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved wellbeing as a result of preserving or improving the human-animal bond | Observed spending on related goods. The cost of insurance premiums for a typical Emergency Boarding program animal (5-year-old Australian Cattle Dog Cross). |

We have chosen the cost of insurance to reflect the value placed on ensuring an animal’s continued wellbeing by their owner. We consider this to be an outcome that continues for the life of the animal. In addition, this is a relationship that strengthens over time, increasing rather than decreasing as animals age. | $1,380 | Choosi: Pet Insurance. Pet insurance comparison website [22] |

| Access to safe accommodation | Observed spending on related goods. The cost of private pet boarding for the average number of days an Emergency Boarding program animal remained in care (39 days). |

RSPCA Emergency Boarding program clients’ animals access safe accommodation either in secure boarding facilities or with foster families. Accessing private pet boarding would provide a similar outcome for these animals hence the cost of private boarding has been used as a proxy. Clients reported in interviews that this would cost around $50 per day through local boarding kennels or veterinary practices. | $1,925 | Client interviews |

| Improved physical health | Observed spending on related goods. The average cost of veterinary treatment per animal that received veterinary treatment while under the care of the Emergency Boarding program. |

Most animals participating in the RSPCA Emergency Boarding program accessed veterinary treatment, whether routine medical care or treatment or injuries or illness and as a result experienced improved physical health. Hence, the average cost of the veterinary treatment provided per animal receiving veterinary treatment through the program was used as the proxy for this outcome. |

$241 |

RSPCA NSW Community Programs records |

| Outcome | Financial Proxy | Rationale | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| More time available to pursue genuine animal cruelty offences | Time use method. Value of an Inspectors time spent pursuing Emergency Boarding programs cases as cruelty or abandonment cases, based on the average hourly rate for Inspectors of $35/hr, assuming 3hrs per week in total are spent assisting potential RSPCA NSW Community Programs cases, 50% of which are likely to be related to the Emergency Boarding program. |

RSPCA Inspectors frequently described their frustration at having to case-manage individuals who would be more appropriately managed through RSPCA NSW Community Programs and that this takes up a considerable amount of their time at work. Hence, we use the value to the Inspectors of being able to use this time for pursuing genuine cruelty offences as a proxy for this outcome. |

$2,730 | Inspector interviews |

| Improved mental health |

Observed spending on related goods. The cost of a typical mental health plan of six sessions with a psychologist at $210 per session. |

RSPCA NSW Inspectors described being relieved of substantial moral distress when they can refer clients to the RSPCA NSW Community Programs. Without this referral pathway, Inspectors’ mental health can be negatively affected. We consider this moral distress comparable with mild anxiety and hence value this outcome using a typical treatment plan for mild anxiety. | $1,260 | Australian Psychological Society [23] |

| Outcome | Proxy Description | Rationale | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fewer animals abandoned without care | Observed spending on related goods. Cost to RSPCA of processing an abandoned animal |

According to interviews with RSPCA Inspectors, animals regularly come into the care of the RSPCA shelter via the Inspectorate because of being abandoned without care. This was also mentioned in interviews with Emergency Boarding program clients. Costs are incurred by RSPCA NSW for retrieving, sheltering and rehabilitating these animals. Hence, the average costs associated with rehabilitating a typical Emergency Boarding program client’s animal (a medium sized adult dog) has been used as the proxy for this outcome. |

$885 | RSPCA records |

| Fewer animals surrendered by their owner | Observed spending on related goods. Cost to RSPCA of processing a surrendered animal |

When asked ‘What do you think would be different for you now if you had not accessed assistance for your animal/s through RSPCA?’ some Emergency Boarding program clients responded that their animal would have been surrendered to a pound or shelter. Hence the average cost to RSPCA NSW of processing a surrendered animal from the time of surrender to adoption has been used as a proxy for this outcome. | $686 | RSPCA records |

| Stakeholder N |

Outcome | Financial Proxy | Outcome Incidence | Deadweight | Attribution | Displacement | Benefit Period (years) |

Drop-Off | Net Social Value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clients 259 |

Extended or enhanced human-animal bond | $3,453 | 93% | 7% | 0% | 25% | 8 | 5% | $1,554,223 |

| Improved mental health and wellbeing | $5,320 | 90% | 7% | 50% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $574,429 | |

| Decreased financial stress | $2,058 | 76% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $376,068 | |

| Increased social inclusion/decreased isolation | $2,778 | 72% | 7% | 50% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $242,274 | |

| Improved personal safety | $3,427 | 41% | 7% | 75% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $85,394 | |

| Improved access to care for themselves | $413 | 59% | 7% | 50% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $29,143 | |

| Improved physical health | $1,140 | 38% | 7% | 75% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $26,039 | |

| Client’s animal/s 627 |

Improved wellbeing as a result of preserving or improving the human-animal bond | $1,380 | 91% | 25% | 0% | 25% | 8 | 0% | $1,249,542 |

| Access to safe accommodation | $1,925 | 71% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $801,776 | |

| Improved physical health | $241 | 71% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $100,315 | |

| RSPCA Inspectors 35 |

More time available to pursue genuine animal cruelty offenses | $2,730 | 80% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $71,089 |

| Improved mental health | $1,260 | 80% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $32,810 | |

| RSPCA NSW shelters | Fewer animals abandoned without care (54 animals; 9% of clients reported their animal would have been abandoned without care) | $885 | 100% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $44,246 |

| Fewer animals surrendered by their owner (233 animals; 37% of clients reported their animal would have been rehomed or surrendered) | $686 | 100% | 25% | 25% | 0% | 1 | N/A | $89,832 |

| Value created for program clients | $2,887,569 |

| Value created for client’s animals | $2,151,633 |

| Value created for RSPCA NSW Inspectors | $103,900 |

| Value created for animal pounds and shelters | $134,078 |

| Total social value created for all stakeholders | $5,277,179 |

| Net Program Investment | $642,489 |

| Social return for each $1 invested | $8.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).