Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Testes component evaluation by ultrasonography

2.1. Anatomy, physiology and vascularization of the testis

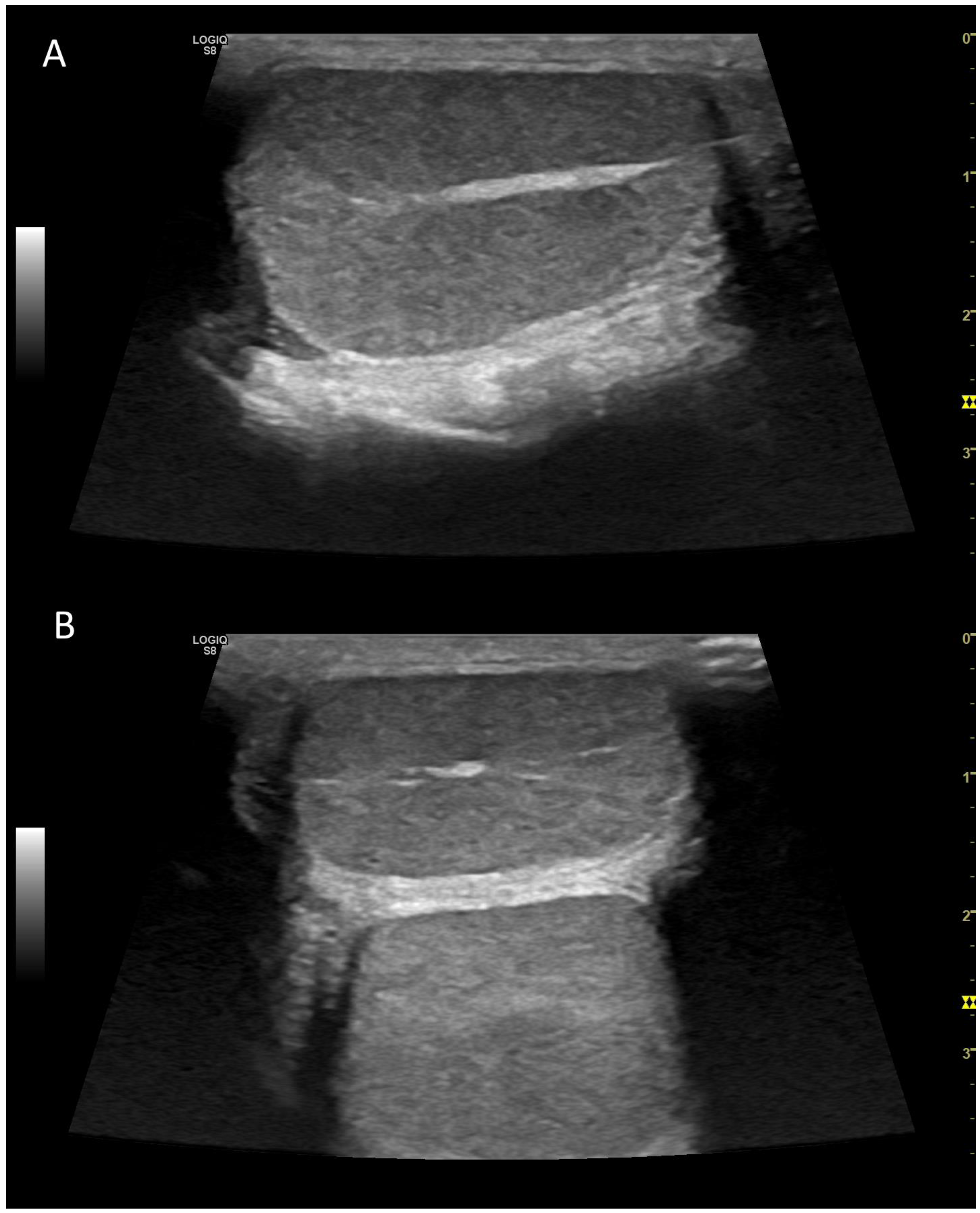

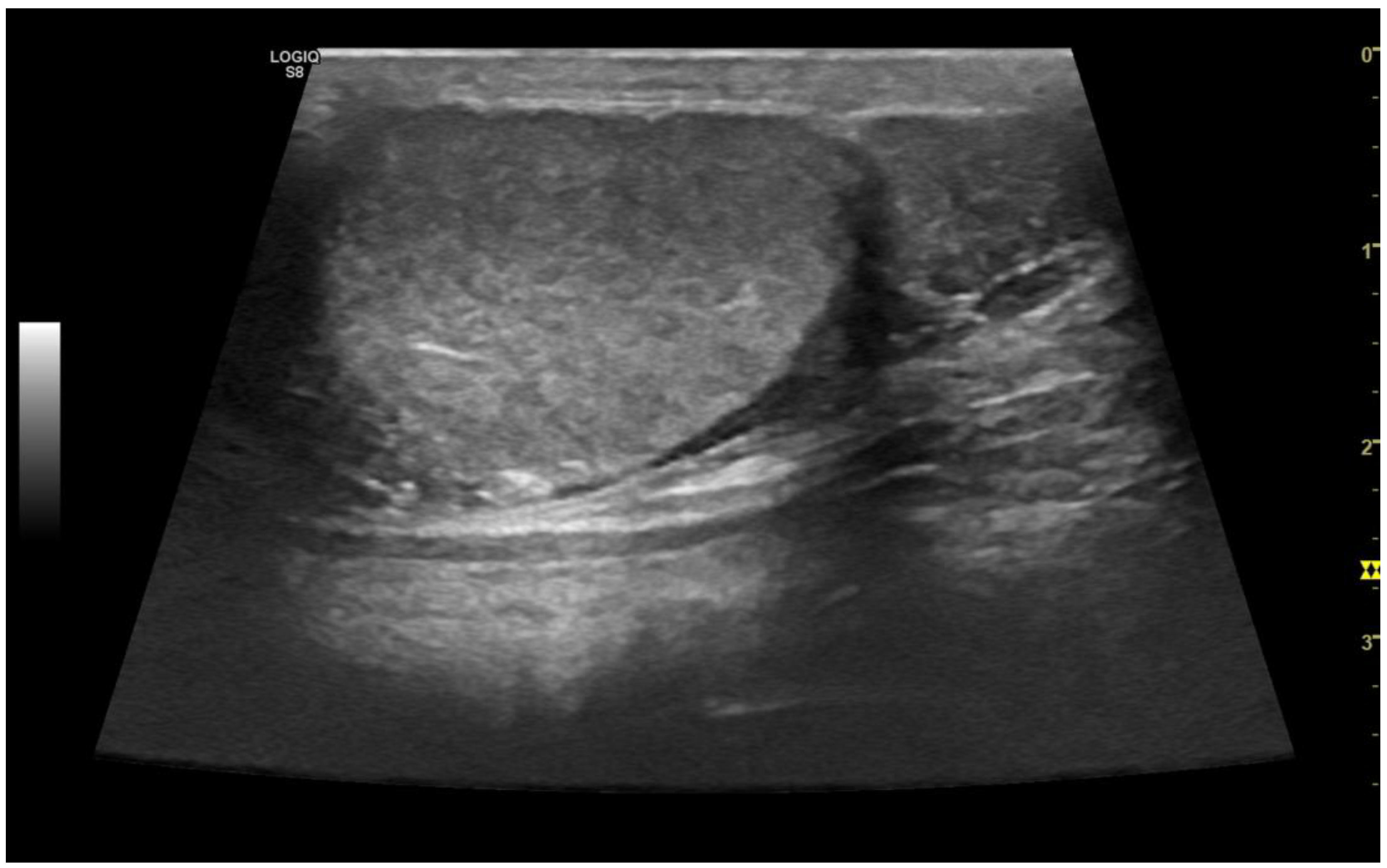

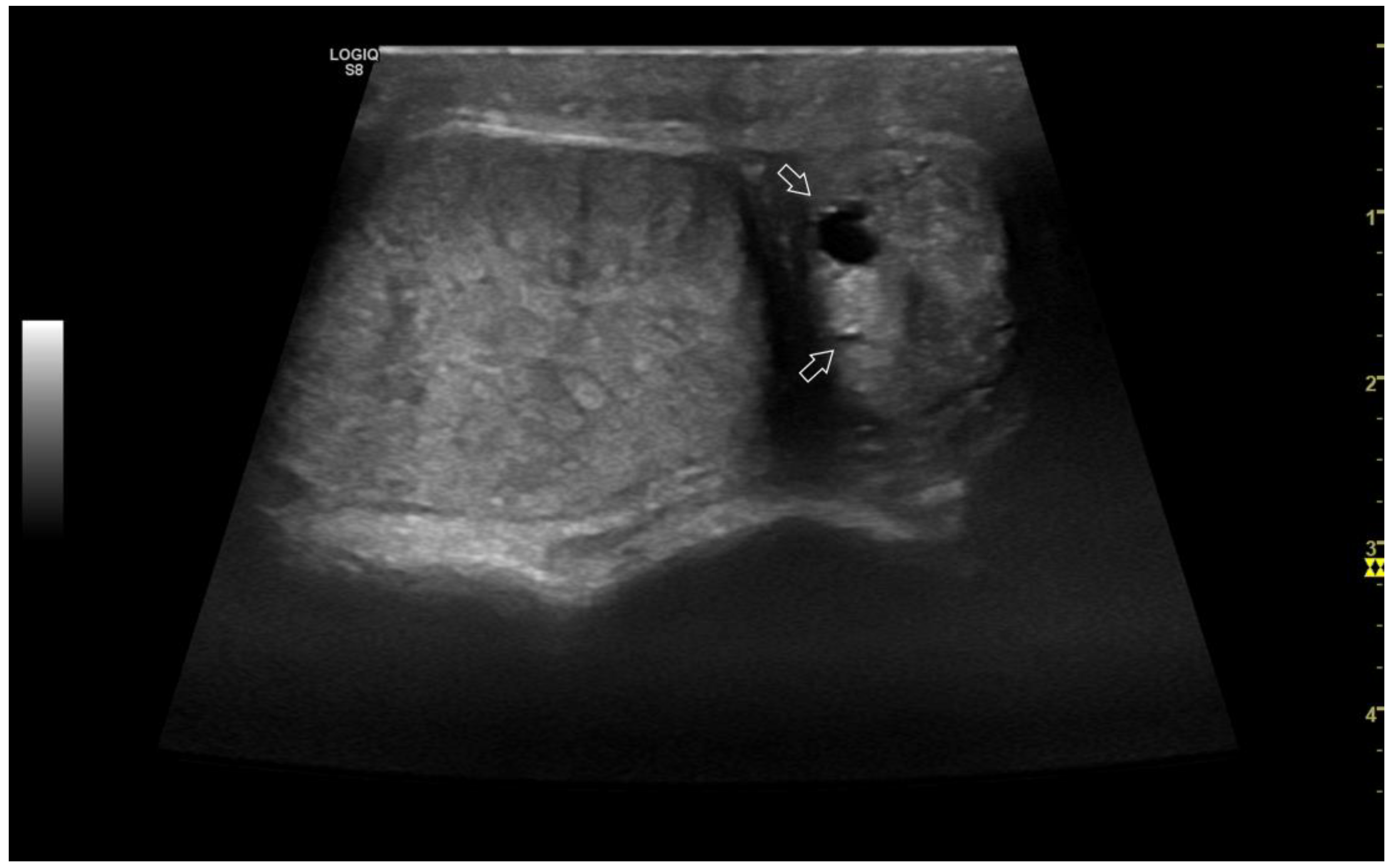

3. Gray-scale ultrasonography

3.1. Technology and applications

3.2. Examination technique

3.3. Normal findings

3.4. Abnormal findings

3.4.1. Intratesticular diseases

3.4.2. Extratesticular diseases

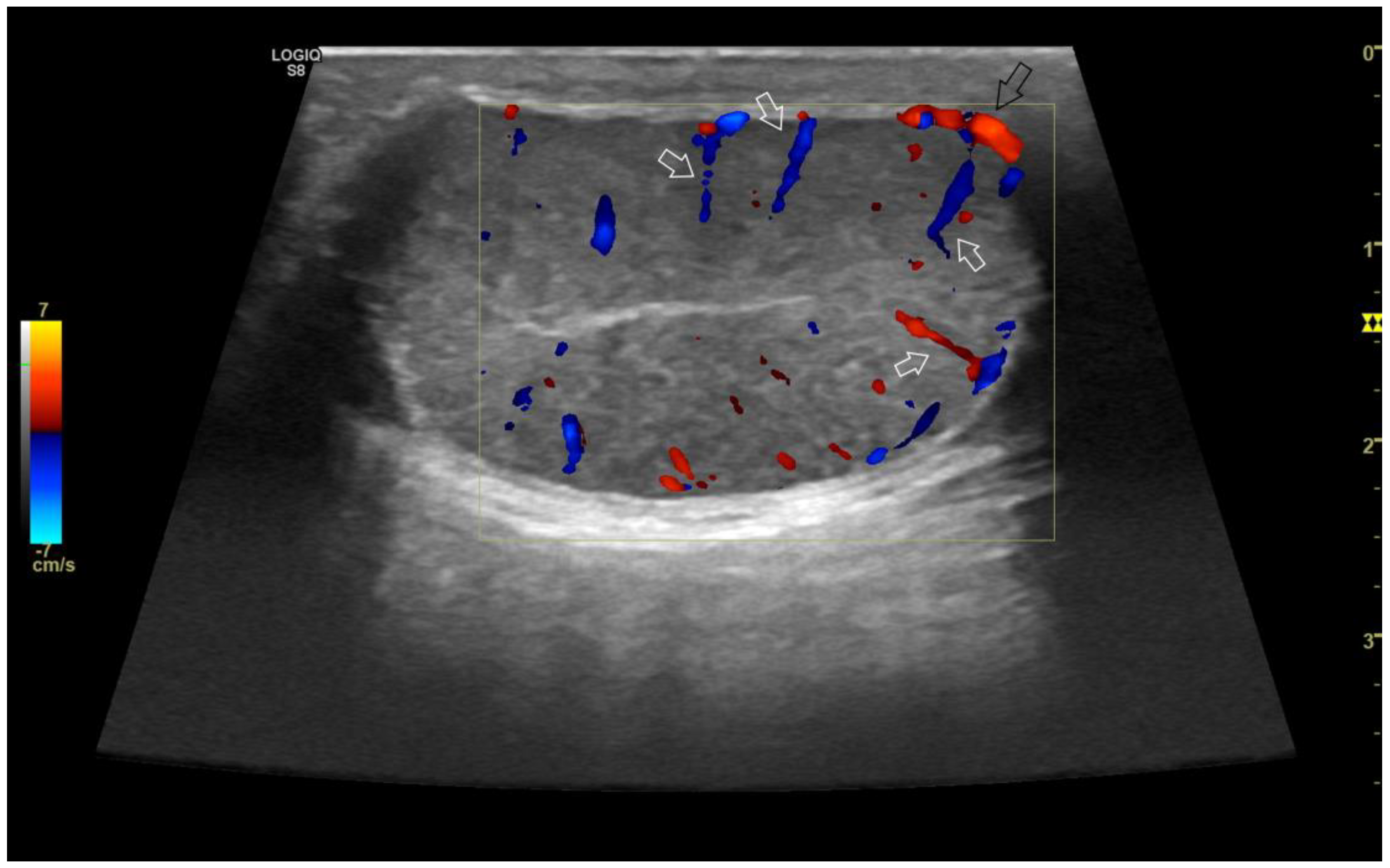

4. Color doppler and power doppler

4.1. Technology and applications

4.2. Normal findings

4.3. Relationship between spectral doppler measurement and dog’s semen quality

4.4. Abnormal findings

5. B-flow

6. Contrast enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS)

6.1. Technology and applications

6.2. Normal findings

6.3. Abnormal findings

7. Ultrasound elastography

7.1. Technology and applications

7.2. Normal findings

7.3. Abnormal findings

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dogra, V.S.; Gottlieb, R.H.; Oka, M.; Rubens, D.J. Sonography of the Scrotum. Radiology 2003, 227, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, G.; Schmidt, C.; Helmich, F.; Stolle, E.; Dieckmann, K.-P. Early Experience with Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Testicular Masses: A Feasibility Study. Urology 2011, 77, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zordo, T.; Stronegger, D.; Pallwein-Prettner, L.; Harvey, C.J.; Pinggera, G.; Jaschke, W.; Aigner, F.; Frauscher, F. Multiparametric Ultrasonography of the Testicles. Nat Rev Urol 2013, 10, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantziaras, G. Imaging of the Male Reproductive Tract: Not so Easy as It Looks Like. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, H.E.; De Lahunta, A.; Miller, M.E. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog; 4. ed.; Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis, Mo, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4377-0812-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kastelic, J.P.; Cook, R.B.; Coulter, G.H. Contribution of the Scrotum, Testes, and Testicular Artery to Scrotal/Testicular Thermoregulation in Bulls at Two Ambient Temperatures. Animal Reproduction Science 1997, 45, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Rodriguez, J.M.; Anel-Lopez, L.; Martín-Muñoz, P.; Álvarez, M.; Gaitskell-Phillips, G.; Anel, L.; Rodríguez-Medina, P.; Peña, F.J.; Ortega Ferrusola, C. Pulse Doppler Ultrasound as a Tool for the Diagnosis of Chronic Testicular Dysfunction in Stallions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, A.; Damber, J.-E. Vascular Controls in Testicular Physiology. In Molecular Biology of the Male Reproductive System; de Kretser, D., Ed.; Academic Press Inc., 1993; pp. 439–468 ISBN 978-0-12-209030-1.

- England Relationship between Ultrasonographic Appearance, Testicular Size, Spermatozoal Output and Testicular Lesions in the Dog. J Small Animal Practice 1991, 32, 306–311. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.R.; Feeney, D.A.; Johnston, S.D.; O’Brien, T.D. Ultrasonographic Features of Testicular Neoplasia in Dogs: 16 Cases (1980-1988). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991, 198, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.R.; Feeney, D.A.; Rivers, B.; Walter, P.A. Diagnostic Imaging of the Male Canine Reproductive Organs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 1991, 21, 553–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, C.R.; Konde, L.J.; Park, R.D. Testicular Ultrasound in the Normal Dog. Veterinary Radiology 1990, 31, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, C.R.; Konde, L.J. Sonographic Evaluation of Canine Testicular and Scrotal Abnormalities: A Review of 26 Case Histories. Veterinary Radiology 1991, 32, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, A.L.; Scortegagna, E.; Nowitzki, K.M.; Kim, Y.H. Ultrasonography of the Scrotum in Adults. Ultrasonography 2016, 35, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.P.; Baker, T.W. Reproductive Ultrasound of the Dog and Tom. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine 2009, 24, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlandi, R.; Vallesi, E.; Boiti, C.; Polisca, A.; Bargellini, P.; Troisi, A. Characterization of Testicular Tumor Lesions in Dogs by Different Ultrasound Techniques. Animals 2022, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattoon, J.S.; Sellon, R.; Berry, C. Small Animal Diagnostic Ultrasound; Fourth.; Elsevier, Inc: Philadelphia, 2020; ISBN 978-0-323-53337-9. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga, A.A.; Barth, A.D.; Brito, L.F.C. Relationship between Semen Quality and Pixel–Intensity of Testicular Ultrasonograms after Scrotal Insulation in Beef Bulls. Theriogenology 2005, 64, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, B.; Lau, C.P.-S.; Giffin, J.; Santos, N.; Hahnel, A.; Raeside, J.; Christie, H.; Bartlewski, P. Suitability of Epididymal and Testicular Ultrasonography and Computerized Image Analysis for Assessment of Current and Future Semen Quality in the Ram. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012, 237, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, L.F.C.; Barth, A.D.; Wilde, R.E.; Kastelic, J.P. Testicular Ultrasonogram Pixel Intensity during Sexual Development and Its Relationship with Semen Quality, Sperm Production, and Quantitative Testicular Histology in Beef Bulls. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Serna, M.; Miguel-Jiménez, S.; Pérez-Pe, R.; Casao, A. Testicular Ultrasound Analysis as a Predictive Tool of Ram Sperm Quality. Biology 2022, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, G.; Bright, L.; Pritchard, B.; Bowen, I.; de Souza, M.; Silva, L.; Moxon, R. Canine Reproductive Ultrasound Examination for Predicting Future Sperm Quality. Reprod Dom Anim 2017, 52, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon, R.; Bright, L.; Pritchard, B.; Bowen, I.M.; Souza, M.B. de; Silva, L.D.M. da; England, G.C.W. Digital Image Analysis of Testicular and Prostatic Ultrasonographic Echogencity and Heterogeneity in Dogs and the Relation to Semen Quality. Animal Reproduction Science 2015, 160, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garolla, A.; Grande, G.; Palego, P.; Canossa, A.; Caretta, N.; Di Nisio, A.; Corona, G.; Foresta, C. Central Role of Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Testicular Function and Genital Tract Obstruction in Infertile Males. Andrology 2021, 9, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.H.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Seo, J.T.; Chun, Y.K. Scrotal US for Evaluation of Infertile Men with Azoospermia. Radiology 2006, 239, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Yoshida, H. Relationship between Testicular Volume and Testicular Function: Comparison of the Prader Orchidometric and Ultrasonographic Measurements in Patients with Infertility. Asian J Andrology 2008, 10, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurich, M.; Aigner, F.; Frauscher, F.; Pallwein, L. The Role of Ultrasound in Assessment of Male Fertility. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2009, 144, S192–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; England, G.C.W.; Catone, G.; Marino, G. Imaging of Canine Neoplastic Reproductive Disorders. Animals 2021, 11, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, S.; Bonaccini, P.; Stelletta, C.; Garolla, A.; Menegazzo, M.; Foresta, C.; Mollo, A.; Milani, C.; Gelli, D. Clinical Use of Testicular Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology in Oligozoospermic and Azoospermic Dogs. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2009, 44, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.B.; Silva, L.D.M.; Moxon, R.; Russo, M.; England, G.C.W. Ultrasonography of the Prostate Gland and Testes in Dogs. In pract. 2017, 39, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouletsou, P.G.; Galatos, A.D.; Leontides, L.S. Comparison between Ultrasonographic and Caliper Measurements of Testicular Volume in the Dog. Animal Reproduction Science 2008, 108, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltiel, H.J.; Diamond, D.A.; Di Canzio, J.; Zurakowski, D.; Borer, J.G.; Atala, A. Testicular Volume: Comparison of Orchidometer and US Measurements in Dogs. Radiology 2002, 222, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantziaras, G.; Alonge, S.; Luvoni, G.C. Ultrasonographic Study of Age-Related Changes on the Size of Prostate and Testicles in Healthy German Shepherd Dogs.; Wroclaw (Poland), 14; p. 150. 20 September.

- Cotchin, E. Testicular Neoplasms in Dogs. Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics 1960, 70, 232–IN12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.A. Common Lesions in the Male Reproductive Tract of Cats and Dogs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2012, 42, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüntzig, K.; Graf, R.; Hässig, M.; Welle, M.; Meier, D.; Lott, G.; Erni, D.; Schenker, N.S.; Guscetti, F.; Boo, G.; et al. The Swiss Canine Cancer Registry: A Retrospective Study on the Occurrence of Tumours in Dogs in Switzerland from 1955 to 2008. Journal of Comparative Pathology 2015, 152, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.A.; Saba, C.F. Tumors of the Male Reproductive System. In Small Animal Clinical Oncology; Elsevier Saunders, 2013; pp. 557–571.

- Liao, A.T.; Chu, P.-Y.; Yeh, L.-S.; Lin, C.-T.; Liu, C.-H. A 12-Year Retrospective Study of Canine Testicular Tumors. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009, 71, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, H.H.L.; Santos, A. dos; Prante, A.L.; Lamego, E.C.; Tondo, L.A.S.; Flores, M.M.; Fighera, R.A.; Kommers, G.D. Testicular Tumors in 190 Dogs: Clinical, Macroscopic and Histopathological Aspects. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2020, 40, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuali, E.; Forte, C.; Porcellato, I.; Brachelente, C.; Sforna, M.; Pavone, S.; Ranciati, S.; Morgante, R.; Crescio, I.M.; Ru, G.; et al. A Five-Year Cohort Study on Testicular Tumors from a Population-Based Canine Cancer Registry in Central Italy (Umbria). Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2020, 185, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, D.F.; Rossi, L.; Pellegrino, C.; Ceppi, M.; Cardellino, U.; Capurro, C.; Ratto, A.; Sambucco, P.L.; Sestito, V.; Tanara, G.; et al. Cancer Incidence in Pet Dogs: Findings of the Animal Tumor Registry of Genoa, Italy. J Vet Intern Med 2008, 22, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosier, J.E. Effect of Aging on Body Systems of the Dog. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 1989, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.L.; Silva, C.M.; Ribeiro, A.F.C.; Serakides, R. Testicular Tumors in Dogs: Frequency and Age Distribution. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2000, 52, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, H.M.; Wilson, G.P.; Pendergrass, T.W.; Cox, V.S. Canine Cryptorchism and Subsequent Testicular Neoplasia: Case-Control Study with Epidemiologic Update. Teratology 1985, 32, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Gartley, C.J.; Khanam, A. Canine Cryptorchidism: An Update. 2018.

- Memon, M.A. Common Causes of Male Dog Infertility. Theriogenology 2007, 68, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxsee, A.L.; Yager, J.A.; Best, S.J.; Foster, R.A. Extratesticular Interstitial and Sertoli Cell Tumors in Previously Neutered Dogs and Cats: A Report of 17 Cases. 2006, 47. 47.

- Bigliardi, E.; Denti, L.; De Cesaris, V.; Bertocchi, M.; Di Ianni, F.; Parmigiani, E.; Bresciani, C.; Cantoni, A.M. Colour Doppler Ultrasound Imaging of Blood Flows Variations in Neoplastic and Non-Neoplastic Testicular Lesions in Dogs. Reprod Dom Anim 2019, 54, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hricak, H.; Lue, T.; Filly, R.A.; Alpers, C.E.; Zeineh, S.J.; Tanagho, E.A. Experimental Study of the Sonographic Diagnosis of Testicular Torsion. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 1983, 2, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felumlee, A.E.; Reichle, J.K.; Hecht, S.; Penninck, D.; Zekas, L.; Dietze Yeager, A.; Goggin, J.M.; Lowry, J. Use of Ultrasound to Locate Retained Testes in Dogs and Cats: Location of Retained Testes. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2012, 53, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, T.J. Color-Flow and Power Doppler Imaging of the Testes. World J Urol 1998, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strina, A.; Corda, A.; Nieddu, S.; Solinas, G.; Lilliu, M.; Zedda, M.T.; Pau, S.; Ledda, S. Annual Variations in Resistive Index (RI) of Testicular Artery, Volume Measurements and Testosterone Levels in Bucks. Comp Clin Pathol 2016, 25, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.M. Power Doppler. Eur Radiol 1999, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Pretorius, D. The Doppler Signal: Where Does It Come from and What Does It Mean? American Journal of Roentgenology 1988, 151, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.B.; Mota Filho, A.C.; Sousa, C.V.S.; Monteiro, C.L.B.; Carvalho, G.G.; Pinto, J.N.; Linhares, J.C.S.; Silva, L.D.M. Triplex Doppler Evaluation of the Testes in Dogs of Different Sizes. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2014, 34, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydos, K.; Baltaci, S.; Salih, M.; Anafarta, K.; Bedük, Y.; Gülsoy, U. Use of Color Doppler Sonography in the Evaluation of Varicoceles. Eur Urol 1993, 24, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; S. , S.; Shetty, S.S.; R., C. Role of High Resolution Sonography and Color Doppler Flow Imaging in the Evaluation of Scrotal Pathology. Int J Res Med Sci 2017, 5, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstman, W.G.; Melson, G.L.; Middleton, W.D.; Andriole, G.L. Testicular Tumors: Findings with Color Doppler US. Radiology 1992, 185, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, W.-H.; Choe, B.-Y.; Byun, J.-Y.; Shinn, K.-S.; Hwang, T.-K. Resistive Index of the Intrascrotal Artery in Scrotal Inflammatory Disease. Acta Radiol 1997, 38, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, F.T.; Winter, D.B.; Madsen, F.A.; Zagzebski, J.A.; Pozniak, M.A.; Chosy, S.G.; Scanlan, K.A. Conventional Color Doppler Velocity Sonography versus Color Doppler Energy Sonography for the Diagnosis of Acute Experimental Torsion of the Spermatic Cord. American Journal of Roentgenology 1996, 167, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotti, F.; Frizza, F.; Balercia, G.; Barbonetti, A.; Behre, H.M.; Calogero, A.E.; Cremers, J.; Francavilla, F.; Isidori, A.M.; Kliesch, S.; et al. The European Academy of Andrology (EAA) Ultrasound Study on Healthy, Fertile Men: An Overview on Male Genital Tract Ultrasound Reference Ranges. Andrology 2022, 10, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, W.; Thorne, D.; Melson, G. Color Doppler Ultrasound of the Normal Testis. American Journal of Roentgenology 1989, 152, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlica, P.; Barozzi, L. Imaging of the Acute Scrotum. European Radiology 2001, 11, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, S.A.A.; Ahmad, I.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Zaheer, S.; Ahmad, K. Role of Color Doppler Ultrasonography in Evaluation of Scrotal Swellings. 2011, 8. 8.

- Sidhu, P.S. Clinical and Imaging Features of Testicular Torsion: Role of Ultrasound. Clinical Radiology 1999, 54, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriprasad, S.; Kooiman, G.G.; Muir, G.H.; Sidhu, P.S. Acute Segmental Testicular Infarction: Differentiation from Tumour Using High Frequency Colour Doppler Ultrasound. BJR 2001, 74, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahed, S.R.; Mohamed, E.-E.M.; Taha, E.A.; Saleh, M.A.; Abdelsalam, Y.M.; ElGanainy, E.O. Sensitivity and Specificity of Ultrasonography in Predicting Etiology of Azoospermia. Urology 2013, 81, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagiotti, G.; Cavallini, G.; Modenini, F.; Vitali, G.; Gianaroli, L. Spermatogenesis and Spectral Echo-Colour Doppler Traces from the Main Testicular Artery. BJU International 2002, 90, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinggera, G.-M.; Mitterberger, M.; Bartsch, G.; Strasser, H.; Gradl, J.; Aigner, F.; Pallwein, L.; Frauscher, F. Assessment of the Intratesticular Resistive Index by Colour Doppler Ultrasonography Measurements as a Predictor of Spermatogenesis. BJU Int 2008, 101, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sihag, P.; Tandon, A.; Pal, R.; Bhatt, S.; Sinha, A.; Sumbul, M. Sonography in Male Infertility: A Useful yet Underutilized Diagnostic Tool. J Ultrasound 2022, 25, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollwein, H.; Scheibenzuber, E.; Stolla, R.; Echte, A.-F.; Sieme, H. Testicular blood flow in the stallion: variability and its relationship to sperm quality and fertility: PHK 2006, 22, 123–133. 22. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ferrusola, C.; Gracia-Calvo, L.; Ezquerra, J.; Pena, F. Use of Colour and Spectral Doppler Ultrasonography in Stallion Andrology. Reprod Dom Anim 2014, 49, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozor M., A.; McDonnell S., M. Doppler Ultrasound Measures of Testicular Blood Flow in Stallions. Theriogenology 2002, 437–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pozor, M.A.; McDonnell, S.M. Color Doppler Ultrasound Evaluation of Testicular Blood Flow in Stallions. Theriogenology 2004, 61, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacem, S.; Papas, M.; Catalan, J.; Miró, J. Examination of Jackass (Equus Asinus) Accessory Sex Glands by B-mode Ultrasound and of Testicular Artery Blood Flow by Colour Pulsed-wave Doppler Ultrasound: Correlations with Semen Production. Reprod Dom Anim 2020, 55, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho Brito, M.; Maronezi, M.C.; Uscategui, R.A.R.; Avante, M.L.; Simões, A.R.; Monteiro, F.O.B.; Feliciano, M.A.R. Metodos Ultrassonográficos Para La Evaluación de Testículos En Gatos. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2018, 23, 6888–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito; Feliciano, M. ; Coutinho, L.; Uscategui, R.; Simões, A.; Maronezi, M.; de Almeida, V.; Crivelaro, R.; Gasser, B.; Pavan, L.; et al. Doppler and Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography of Testicles in Adult Domestic Felines. Reprod Dom Anim 2015, 50, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloria, A.; Carluccio, A.; Wegher, L.; Robbe, D.; Valorz, C.; Contri, A. Pulse Wave Doppler Ultrasound of Testicular Arteries and Their Relationship with Semen Characteristics in Healthy Bulls. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 2018, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, F.A.B.; Junior, C.K.; Fávaro, P. da C.; Pereira, G.R.; Morotti, F.; Menegassi, S.R.O.; Barcellos, J.O.J.; Seneda, M.M. Effect of Breed on Testicular Blood Flow Dynamics in Bulls. Theriogenology 2018, 118, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, H.; Elweza, A.; Sharshar, A. Testicular Color Doppler Ultrasonography in Barki Rams. AJVS 2019, 61, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedia M., G.; El-Belely M., S. Testicular Morphometric and Echotextural Parameters and Their Correlation with Intratesticular Blood Flow in Ossimi Ram Lambs. Large Animal Review 2021, 27, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Samir, H.; Nyametease, P.; Nagaoka, K.; Watanabe, G. Effect of Seasonality on Testicular Blood Flow as Determined by Color Doppler Ultrasonography and Hormonal Profiles in Shiba Goats. Animal Reproduction Science 2018, 197, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito; da Rosa Filho, R. R.; Losano, J.D.A.; Vannucchi, C.I. Ageing Changes Testes and Epididymis Blood Flow without Altering Biometry and Echodensity in Dogs. Animal Reproduction Science 2021, 228, 106745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, J.; Soler, M.; Lucas, X.; Agut, A. Colour and Pulsed Doppler Ultrasonographic Study of the Canine Testis: Doppler Ultrasound Testis Dog. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2012, 47, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.B.; Barbosa, C.C.; England, G.; Mota Filho, A.C.; Sousa, C.; de Carvalho, G.G.; Silva, H.; Pinto, J.N.; Linhares, J.; Silva, L. Regional Differences of Testicular Artery Blood Flow in Post Pubertal and Pre-Pubertal Dogs. BMC Vet Res 2015, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, M.B.; England, G.C.W.; Mota Filho, A.C.; Ackermann, C.L.; Sousa, C.V.S.; de Carvalho, G.G.; Silva, H.V.R.; Pinto, J.N.; Linhares, J.C.S.; Oba, E.; et al. Semen Quality, Testicular B-Mode and Doppler Ultrasound, and Serum Testosterone Concentrations in Dogs with Established Infertility. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, M.B.; da Cunha Barbosa, C.; Pereira, B.S.; Monteiro, C.L.B.; Pinto, J.N.; Linhares, J.C.S.; da Silva, L.D.M. Doppler Velocimetric Parameters of the Testicular Artery in Healthy Dogs. Research in Veterinary Science 2014, 96, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloria, A.; Di Francesco, L.; Marruchella, G.; Robbe, D.; Contri, A. Pulse-Wave Doppler Pulsatility and Resistive Indexes of the Testicular Artery Increase in Canine Testis with Abnormal Spermatogenesis. Theriogenology 2020, 158, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbsch, P.; Holzmann, A.; Gabler, C. Colour-Coded Duplex Sonography of the Testes of Dogs. Veterinary Record 2002, 151, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunzel-Apel, A.-R.; Mohrke, C.; Nautrup, C.P. Colour-Coded and Pulsed Doppler Sonography of the Canine Testis, Epididymis and Prostate Gland: Physiological and Pathological Findings. Reprod Domest Anim 2001, 36, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, H.; Dorado, J.; Hidalgo, M.; Gaivão, I.; Martins-Bessa, A. Assessment of Dog Testis Perfusion by Colour and Pulsed-Doppler Ultrasonography and Correlation With Sperm Oxidative DNA Damage. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine 2020, 41, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautwein, L.G.C.; Souza, A.K.; Martins, M.I.M. Can Testicular Artery Doppler Velocimetry Values Change According to the Measured Region in Dogs? Reprod Dom Anim 2019, 54, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelli, R.; Troisi, A.; Elad Ngonput, A.; Cardinali, L.; Polisca, A. Evaluation of Testicular Artery Blood Flow by Doppler Ultrasonography as a Predictor of Spermatogenesis in the Dog. Research in Veterinary Science 2013, 95, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, H.; Radwan, F.; Watanabe, G. Advances in Applications of Color Doppler Ultrasonography in the Andrological Assessment of Domestic Animals: A Review. Theriogenology 2021, 161, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, A.; Ruiz, S. New Approaches to Assess Fertility in Domestic Animals: Relationship between Arterial Blood Flow to the Testicles and Seminal Quality. Animals 2020, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schärz, M.; Ohlerth, S.; Achermann, R.; Gardelle, O.; Roos, M.; Saunders, H.M.; Wergin, M.; Kaser-Hotz, B. Evaluation of Quantified Contrast-Enhanced Color and Power Doppler Ultrasonography for the Assessment of Vascularity and Perfusion of Naturally Occurring Tumors in Dogs. ajvr 2005, 66, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, A.G.; Mlekusch, I.; Wickenhauser, G.; Assadian, A.; Taher, F. Clinical Applications of B-Flow Ultrasound: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.A.; Jha, P.; Poder, L.; Weinstein, S. Advanced Ultrasound Applications in the Assessment of Renal Transplants: Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound, Elastography, and B-Flow. Abdom Radiol 2018, 43, 2604–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, A.; Yamada, K. B-Mode Flow Imaging of the Carotid Artery. Stroke 2001, 32, 2055–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsberg, R.H. B-Flow, a Non-Doppler Technology for Flow Mapping: Early Experience in the Abdomen. Ultrasound Quarterly 2003, 19, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsberg, R.H. B-Flow Imaging of the Hepatic Vasculature: Correlation with Color Doppler Sonography. American Journal of Roentgenology 2007, 188, W522–W533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino-Rocha, A.I.; Silva, A.; Gabriel, J.; Teixeira-Guedes, C.I.; Lopes, C.; Gil da Costa, R.; Gama, A.; Ferreira, R.; Oliveira, P.A.; Ginja, M. Ultrasonographic, Thermographic and Histologic Evaluation of MNU-Induced Mammary Tumors in Female Sprague-Dawley Rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2013, 67, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino-Rocha, A.I.; Gama, A.; Oliveira, P.A.; Vanderperren, K.; Saunders, J.H.; Pires, M.J.; Ferreira, R.; Ginja, M. A Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonographic Study About the Impact of Long-Term Exercise Training on Mammary Tumor Vascularization: Exercise Training and Mammary Tumor Vascularization. J Ultrasound Med 2017, 36, 2459–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, A.L.; Meijer, R.I.; Poelgeest, E.; Spoor, P.; Serné, E.H.; Eringa, E.C. Contrast-enhanced Ultrasound for Quantification of Tissue Perfusion in Humans. Microcirculation 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlichman, D.B.; Weiss, A.; Koenigsberg, M.; Stein, M.W. Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound: A Review of Radiology Applications. Clinical Imaging 2020, 60, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, H.T.; Kristensen, A.T.; Kjelgaard-Hansen, M.; McEvoy, F.J. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography in Normal Canine Liver. Evaluation of Imaging and Safety Parameters. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2005, 46, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canejo-Teixeira, R.; Lima, A.; Santana, A. Applications of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Splenic Studies of Dogs and Cats. Animals 2022, 12, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correas, J.-M.; Bridal, L.; Lesavre, A.; Méjean, A.; Claudon, M.; Hélénon, O. Ultrasound Contrast Agents: Properties, Principles of Action, Tolerance, and Artifacts. Eur Radiol 2001, 11, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haers, H.; Saunders, J.H. Review of Clinical Characteristics and Applications of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography in Dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2009, 234, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, A.; Manfredi, S.; Vignoli, M.; Russo, M.; England, G.; Rossi, F.; Bigliardi, E.; Di Ianni, F.; Parmigiani, E.; Bresciani, C.; et al. Use of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography in Chronic Pathologic Canine Testes. Reprod Dom Anim 2014, 49, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioanitescu, E.S.; Copaci, I.; Mindrut, E.; Motoi, O.; Stanciu, A.M.; Toma, L.; Iliescu, E.L. Various Aspects of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography in Splenic Lesions—a Pictorial Essay. Med Ultrason 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloth, C.; Kratzer, W.; Schmidberger, J.; Beer, M.; Clevert, D.A.; Graeter, T. Ultrasound 2020—Diagnostics & Therapy: On the Way to Multimodal Ultrasound: Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS), Microvascular Doppler Techniques, Fusion Imaging, Sonoelastography, Interventional Sonography. Rofo 2021, 193, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolotto, M.; Derchi, L.E.; Sidhu, P.S.; Serafini, G.; Valentino, M.; Grenier, N.; Cova, M.A. Acute Segmental Testicular Infarction at Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound: Early Features and Changes During Follow-Up. American Journal of Roentgenology 2011, 196, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caretta, N.; Palego, P.; Schipilliti, M.; Torino, M.; Pati, M.; Ferlin, A.; Foresta, C. Testicular Contrast Harmonic Imaging to Evaluate Intratesticular Perfusion Alterations in Patients With Varicocele. Journal of Urology 2010, 183, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, V.; Sellars, M.E.; Sharma, D.M.; Sidhu, P.S. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Testicular Trauma: Role in Directing Exploration, Debridement and Organ Salvage. BJR 2012, 85, e65–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentino, M.; Bertolotto, M.; Derchi, L.; Bertaccini, A.; Pavlica, P.; Martorana, G.; Barozzi, L. Role of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound in Acute Scrotal Diseases. Eur Radiol 2011, 21, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagumo, T.; Ishigaki, K.; Yoshida, O.; Sakurai, N.; Terai, K.; Heishima, T.; Asano, K. Quantitative Analysis of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Estimates Intrahepatic Portal Vascularity in Dogs with Single Extrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt. ajvr 2022, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, R.T.; Iani, M.; Matheson, J.; Delaney, F.; Young, K. Contrast Harmonic Ultrasound of Spontaneous Liver Nodules in 32 Dogs. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2004, 45, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwei, R.M.; O’Brien, R.T.; Matheson, J.S. Characterization of Lymphomatous Lymph Nodes in Dogs Using Contrast Harmonic and Power Doppler Ultrasound. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2005, 46, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, M.; Ohta, H.; Nisa, K.; Osuga, T.; Sasaki, N.; Morishita, K.; Takiguchi, M. Contrast-enhanced Ultrasonography Is a Feasible Technique for Quantifying Hepatic Microvascular Perfusion in Dogs with Extrahepatic Congenital Portosystemic Shunts. Vet Radiol Ultrasound, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, M.; Rychlik, A.; Nieradka, R.; Nowicki, M. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography (CEUS) in Canine Liver Examination. Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2010, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, L.E.; O’Brien, R.T.; Waller, K.R.; Zagzebski, J.A. Quantitative Contrast Harmonic Ultrasound Imaging of Normal Canine Liver. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2003, 44, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotta, A.F.; Gomes, M.C.; Rocha, N.S.; Melchert, A.; Giuffrida, R.; Silva, J.P.; Mamprim, M.J. Sonography and Sonoelastography in the Detection of Malignancy in Superficial Lymph Nodes of Dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2019, 33, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschen, L.; Angelette, N.; Stout, R. Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Ultrasonography of Medial Iliac Lymph Nodes in Healthy Dogs: Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography of Lymph Nodes. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2010, 51, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-Y.; Jeong, W.-C.; Lee, Y.-W.; Choi, H.-J. Contrast Enhanced Ultrasonography of Kidney in Conscious and Anesthetized Beagle Dogs. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2016, 78, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, K.R.; O’Brien, R.T.; Zagzebski, J.A. Quantitative Contrast Ultrasound Analysis of Renal Perfusion in Normal Dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2007, 48, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Neitman, J.L.; O’Brien, R.T.; Wallace, J.D. Quantitative Perfusion Analysis of the Pancreas and Duodenum in Healthy Dogs by Use of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography. ajvr 2012, 73, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademacher, N.; Ohlerth, S.; Scharf, G.; Laluhova, D.; Sieber-Ruckstuhl, N.; Alt, M.; Roos, M.; Grest, P.; Kaser-Hotz, B. Contrast-Enhanced Power and Color Doppler Ultrasonography of the Pancreas in Healthy and Diseased Cats. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2008, 22, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blohm, K.; Hittmair, K.M.; Tichy, A.; Nell, B. Quantitative, Noninvasive Assessment of Intra- and Extraocular Perfusion by Contrast-enhanced Ultrasonography and Its Clinical Applicability in Healthy Dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2019, 22, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blohm, K.; Tichy, A.; Nell, B. Clinical Utility, Dose Determination, and Safety of Ocular Contrast-enhanced Ultrasonography in Horses: A Pilot Study. Vet Ophthalmol 2020, 23, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Park, S.; Lee, D.; Cha, A.; Kim, D.; Choi, J. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Evaluation of Blood Perfusion in Normal Canine Eyes. Vet Ophthalmol 2019, 22, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, S.; Di Pietro, S.; Cicero, L.; Falcone, A.; Liotta, L.; Crupi, R.; Cassata, G.; Macrì, F. Impact of Region-of-Interest Size and Location on Quantitative Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound of Canine Splenic Perfusion. BMC Vet Res 2021, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Sasaki, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Ohta, H.; Hwang, S.-J.; Mimura, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Takiguchi, M. Quantitative Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography of Canine Spleen. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2009, 50, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Sasaki, N.; Murakami, M.; Bandula Kumara, W.R.; Ohta, H.; Yamasaki, M.; Takagi, S.; Osaki, T.; Takiguchi, M. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Characterization of Focal Splenic Lesions in Dogs: Contrast Ultrasound of Splenic Lesions. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2010, 24, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlerth, S.; Rüefli, E.; Poirier, V.; Roos, M.; Kaser-Hotz, B. Contrast Harmonic Imaging of the Normal Canine Spleen. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2007, 48, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krg̈er Hagen, E.; Forsberg, F.; Liu, J.-B.; Gomella, L.G.; Aksnes, A.-K.; Merton, D.A.; Johnson, D.; Goldberg, B.B. Contrast-Enhanced Power Doppler Imaging of Normal and Decreased Blood Flow in Canine Prostates. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2001, 27, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Vignoli, M.; Catone, G.; Rossi, F.; Attanasi, G.; England, G. Prostatic Perfusion in the Dog Using Contrast-Enhanced Doppler Ultrasound. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2009, 44, 334–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Vignoli, M.; England, G. B-Mode and Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonographic Findings in Canine Prostatic Disorders. Reprod Domest Anim 2012, 47, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, A.; Orlandi, R.; Bargellini, P.; Menchetti, L.; Borges, P.; Zelli, R.; Polisca, A. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonographic Characteristics of the Diseased Canine Prostate Gland. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, M.; Russo, M.; Catone, G.; Rossi, F.; Attanasi, G.; Terragni, R.; Saunders, J.; England, G. Assessment of Vascular Perfusion Kinetics Using Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Prostatic Disease in Dogs: Prostatic Perfusion Kinetics Assessed by CEUS. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2011, 46, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillaert, A.; Stock, E.; Duchateau, L.; de Rooster, H.; Devriendt, N.; Vanderperren, K. B-Mode and Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography Aspects of Benign and Malignant Superficial Neoplasms in Dogs: A Preliminary Study. Animals 2022, 12, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillaert, A.; Stock, E.; Favril, S.; Duchateau, L.; Saunders, J.H.; Vanderperren, K. Intra- and Inter-Observer Variability of Quantitative Parameters Used in Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound of Kidneys of Healthy Cats. Animals 2022, 12, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademacher, N.; Schur, D.; Gaschen, F.; Kearney, M.; Gaschen, L. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography of the Pancreas in Healthy Dogs and in Dogs with Acute Pancreatitis: Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Canine Pancreatitis. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2016, 57, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, J.; Céspedes, I.; Ponnekanti, H.; Yazdi, Y.; Li, X. Elastography: A Quantitative Method for Imaging the Elasticity of Biological Tissues. Ultrason Imaging 1991, 13, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correas; Drakonakis, E. ; Isidori, A.M.; Hélénon, O.; Pozza, C.; Cantisani, V.; Di Leo, N.; Maghella, F.; Rubini, A.; Drudi, F.M.; et al. Update on Ultrasound Elastography: Miscellanea. Prostate, Testicle, Musculo-Skeletal. European Journal of Radiology 2013, 82, 1904–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, J.; Cosgrove, D.; Dietrich, C.; Fromageau, J.; Bojunga, J.; Calliada, F.; Cantisani, V.; Correas, J.-M.; D’Onofrio, M.; Drakonaki, E.; et al. EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Ultrasound Elastography. Part 1: Basic Principles and Technology. Ultraschall in Med 2013, 34, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, R.M.S.; Liau, J.; Kaffas, A.E.; Chammas, M.C.; Willmann, J.K. Ultrasound Elastography: Review of Techniques and Clinical Applications. Theranostics 2017, 7, 1303–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Snedeker, J.G. Elastography: Modality-Specific Approaches, Clinical Applications, and Research Horizons. Skeletal Radiol 2011, 40, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, R.G. Sonographic Breast Elastography: A Primer. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 2012, 31, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, A.; Ueno, E.; Tohno, E.; Kamma, H.; Takahashi, H.; Shiina, T.; Yamakawa, M.; Matsumura, T. Breast Disease: Clinical Application of US Elastography for Diagnosis. Radiology 2006, 239, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvière, O.; Melodelima, C.; Hoang Dinh, A.; Bratan, F.; Pagnoux, G.; Sanzalone, T.; Crouzet, S.; Colombel, M.; Mège-Lechevallier, F.; Souchon, R. Stiffness of Benign and Malignant Prostate Tissue Measured by Shear-Wave Elastography: A Preliminary Study. Eur Radiol 2017, 27, 1858–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddi, A.; Sacchi, A.; Magistretti, G.; Almolla, J.; Salvadore, M. Real-Time Tissue Elastography for Testicular Lesion Assessment. Eur Radiol 2012, 22, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muršić, M. The Role of Ultrasound Elastography in the Diagnosis of Pathologic Conditions of Testicles and Scrotum. ACC 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocher, L.; Criton, A.; Gennisson, J.-L.; Izard, V.; Ferlicot, S.; Tanter, M.; Benoit, G.; Bellin, M.F.; Correas, J.-M. Testicular Shear Wave Elastography in Normal and Infertile Men: A Prospective Study on 601 Patients. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2017, 43, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, A.; Bradley, K.; Birch, S.; Browne, W.J.; Barberet, V. Elastography of the Normal Canine Liver, Spleen and Kidneys: Canine Elastography. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2014, 55, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.-K.; Kim, H.; Yu, D.; Choi, J. Ultrasonographic Elastography of the Liver, Spleen, Kidneys, and Prostate in Clinically Normal Beagle Dogs: Ultrasonographicx Elastography in Normal Dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2015, 56, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciano, M.A.R.; Maronezi, M.C.; Simões, A.P.R.; Uscategui, R.R.; Maciel, G.S.; Carvalho, C.F.; Canola, J.C.; Vicente, W.R.R. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Elastography of Prostate and Testes of Healthy Dogs: Preliminary Results. J Small Anim Pract 2015, 56, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cintra, C.A.; Feliciano, M.A.R.; Santos, V.J.C.; Maronezi, M.C.; Cruz, I.K.; Gasser, B.; Silva, P.; Crivellenti, L.Z.; Uscategui, R.A.R. Applicability of ARFI Elastography in the Evaluation of Canine Prostatic Alterations Detected by B-Mode and Doppler Ultrasonography. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2020, 72, 2135–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, S.; Feliciano, M.A.R.; Borin-Crivellenti, S.; Crivellenti, L.Z.; Maronezi, M.C.; Simões, A.P.R.; Silva, P.D.A.; Uscategui, R.R.; Cruz, N.R.N.; Santana, A.E.; et al. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) Elastography of Adrenal Glands in Healthy Adult Dogs. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2017, 69, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizzi, G.; Crepaldi, P.; Roccabianca, P.; Morabito, S.; Zini, E.; Auriemma, E.; Zanna, G. Strain Elastography for the Assessment of Skin Nodules in Dogs. Vet Dermatol 2021, 32, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favril, S.; Stock, E.; Broeckx, B.J.G.; Devriendt, N.; de Rooster, H.; Vanderperren, K. Shear Wave Elastography of Lymph Nodes in Dogs with Head and Neck Cancer: A Pilot Study. Vet Comparative Oncology 2022, 20, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Yang, S.; Suh, G.; Choi, J. Correlating Two-Dimensional Shear Wave Elastography of Acute Pancreatitis with Spec CPL in Dogs. J Vet Sci 2022, 23, e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spużak, J.; Kubiak, K.; Glińska-Suchocka, K.; Jankowski, M.; Borusewicz, P.; Kubiak-Nowak, D. Accuracy of Real-Time Shear Wave Elastography in the Assessment of Normal Small Intestine Mucosa in Dogs. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Simões, A.P.; Cristina Maronezi, M.; Andres Ramirez Uscategui, R.; Garcia Kako Rodrigues, M.; Sitta Gomes Mariano, R.; Tavares de Almeida, V.; José Correia Santos, V.; Del Aguila da Silva, P.; Ricardo Russiano Vicente, W.; Antonio Rossi Feliciano, M. Placental ARFI Elastography and Biometry Evaluation in Bitches. Animal Reproduction Science 2020, 214, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Simões, A.P.; Rossi Feliciano, M.A.; Maronezi, M.C.; Uscategui, R.A.R.; Bartlewski, P.M.; de Almeida, V.T.; Oh, D.; do Espírito Santo Silva, P.; da Silva, L.C.G.; Russiano Vicente, W.R. Elastographic and Echotextural Characteristics of Foetal Lungs and Liver during the Final 5 Days of Intrauterine Development in Dogs. Animal Reproduction Science 2018, 197, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, M.A.R.; Maronezi, M.C.; Pavan, L.; Castanheira, T.L.; Simões, A.P.R.; Carvalho, C.F.; Canola, J.C.; Vicente, W.R.R. ARFI Elastography as a Complementary Diagnostic Method for Mammary Neoplasia in Female Dogs—Preliminary Results. J Small Anim Pract 2014, 55, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glińska-Suchocka, K.; Jankowski, M.; Kubiak, K.; Spużak, J.; Nicpon, J. Application of Shear Wave Elastography in the Diagnosis of Mammary Gland Neoplasm in Dogs. Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2013, 16, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimini, M.; Gloria, A.; Romanucci, M.; Della Salda, L.; Di Francesco, L.; Contri, A. Strain and Shear-Wave Elastography and Their Relationship to Histopathological Features of Canine Mammary Nodular Lesions. Veterinary Sciences 2022, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito; Feliciano; Coutinho ARFI Elastography of Healthy Adults Felines Testes. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae 2015, 43.

- Feliciano, M.A.R.; Maronezi, M.C.; Simões, A.P.R.; Maciel, G.S.; Pavan, L.; Gasser, B.; Silva, P.; Uscategui, R.R.; Carvalho, C.F.; Canola, J.C.; et al. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) Elastography of Testicular Disorders in Dogs: Preliminary Results. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2016, 68, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glińska-Suchocka, K.; Jankowski, M.; Kubiak, K.; Spużak, J.; Dzimira, S. Sonoelastography in Differentiation of Benign and Malignant Testicular Lesion in Dogs. 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).