Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Protein restriction

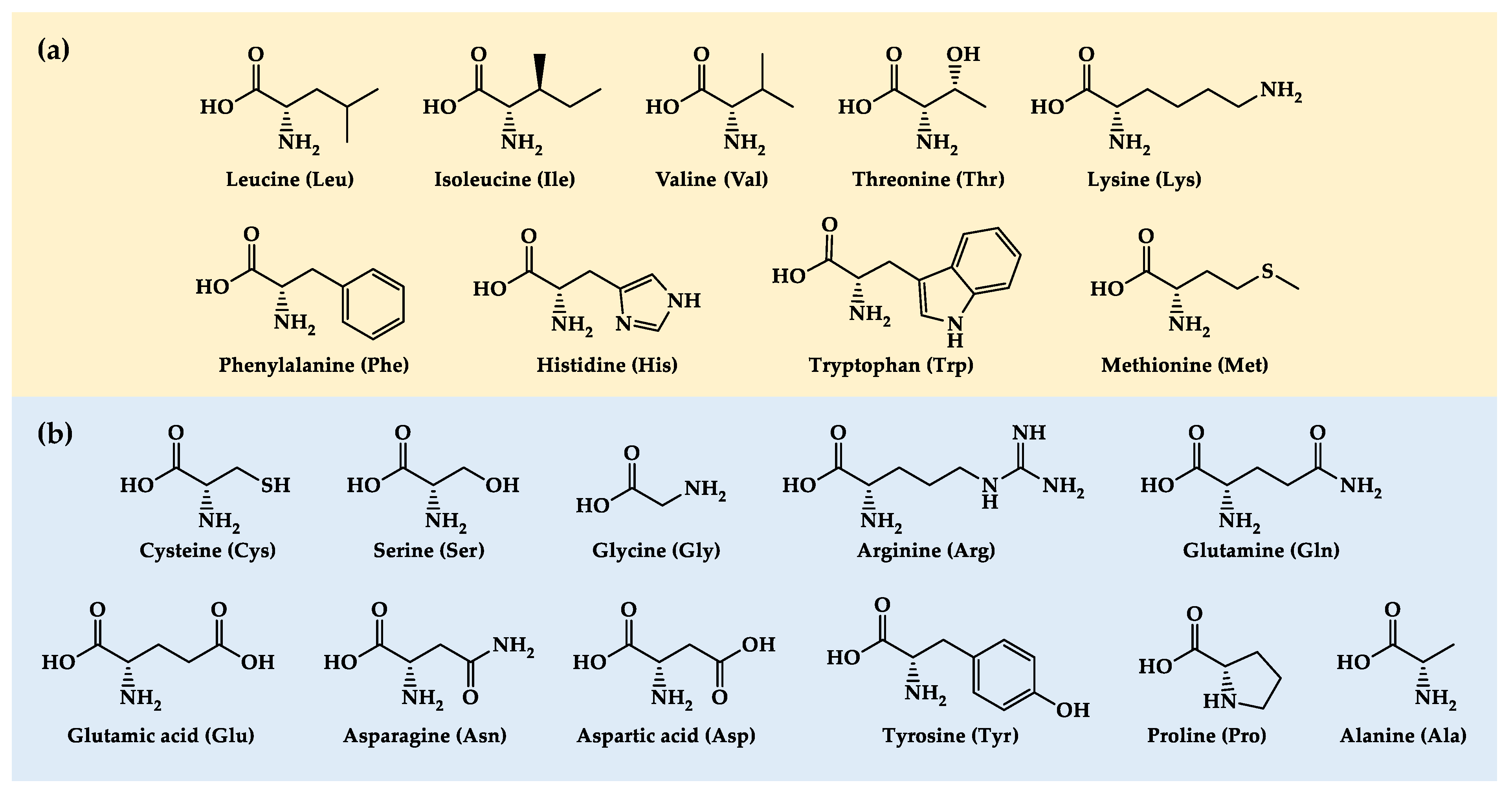

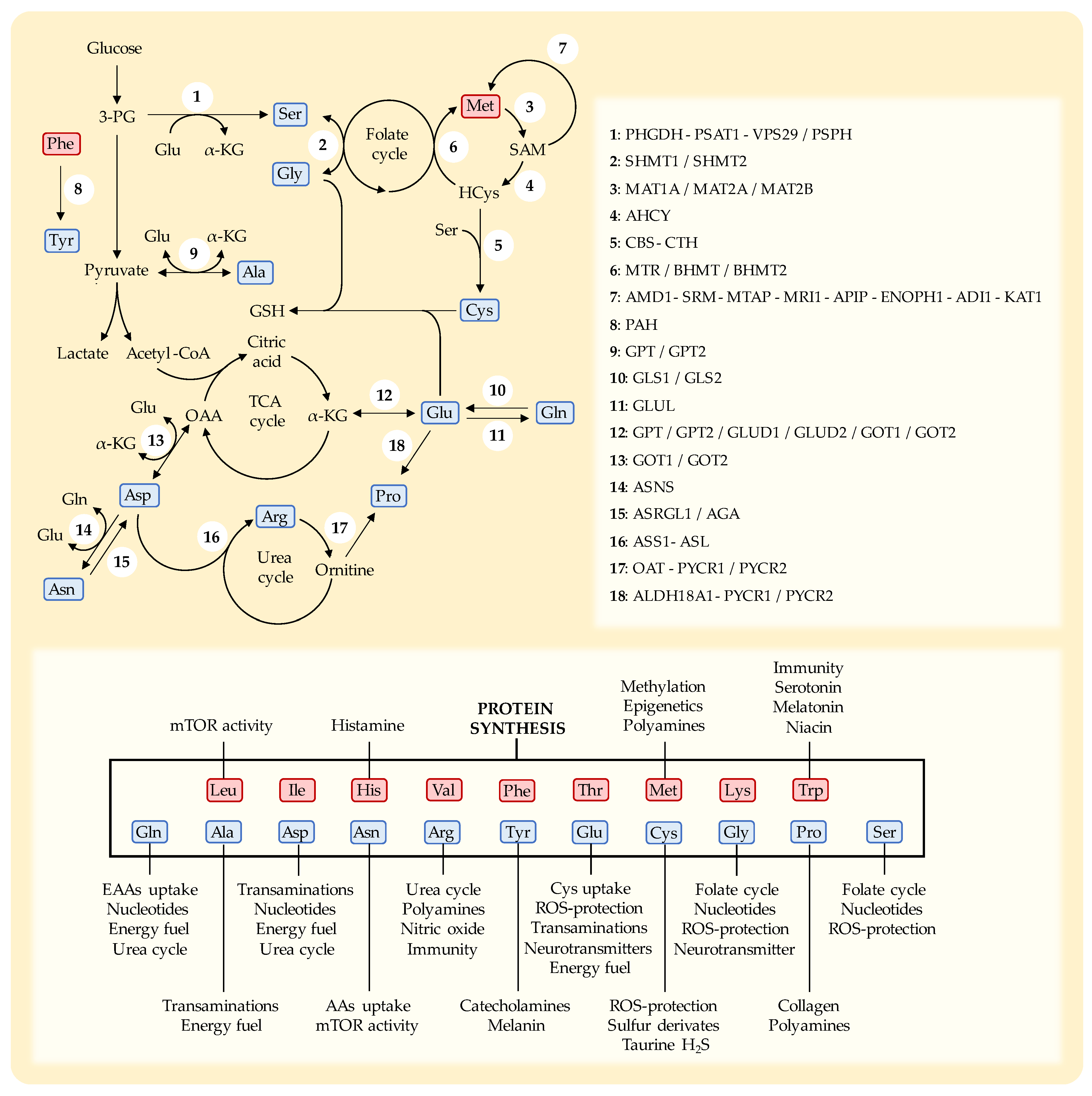

3. Essential Amino Acids

3.1. Leucine

3.2. Isoleucine

3.3. Valine

3.4. Threonine

3.5. Lysine

3.6. Phenylalanine

3.7. Histidine

3.8. Tryptophan

3.9. Methionine

4. Non-Essential Amino Acids

4.1. Cysteine

4.2. Serine

4.3. Glycine

4.4. Arginine

4.5. Glutamine

4.6. Glutamate

4.7. Asparagine

4.8. Aspartate

4.9. Tyrosine

4.10. Alanine

4.11. Proline

5. Manipulation of Multiple Amino Acids Simultaneously

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warburg, O. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakoglu, L.; Agress, H.; Goldsmith, S.J. Clinical Role of FDG PET in Evaluation of Cancer Patients. Radiographics 2003, 23, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Haim, S.; Ell, P. 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT in the Evaluation of Cancer Treatment Response. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Lazaro, M. The Warburg Effect: Why and How Do Cancer Cells Activate Glycolysis in the Presence of Oxygen? Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro, M. Does Hypoxia Really Control Tumor Growth? Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2006, 28, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lazaro, M. A New View of Carcinogenesis and an Alternative Approach to Cancer Therapy. Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro, M. Excessive Superoxide Anion Generation Plays a Key Role in Carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 1378–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro, M. Dual Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Cancer: Possible Relevance to Cancer Chemoprevention and Therapy. Cancer Lett. 2007, 252, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Tew, K.D. Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Zhu, J.; Thompson, C.B. The Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism: Still Emerging. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stine, Z.E.; Schug, Z.T.; Salvino, J.M.; Dang, C.V. Targeting Cancer Metabolism in the Era of Precision Oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Pardella, E.; Paoli, P.; Fendt, S.-M.; Taddei, M.L. Metabolic Reprogramming in Anticancer Drug Resistance: A Focus on Amino Acids. Trends in Cancer 2021, 7, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergers, G.; Fendt, S.-M. The Metabolism of Cancer Cells during Metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, X.; Cheng, C.; Yu, W.; Yi, P. Metabolism of Amino Acids in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endicott, M.; Jones, M.; Hull, J. Amino Acid Metabolism as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer: A Review. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukey, M.J.; Katt, W.P.; Cerione, R.A. Targeting Amino Acid Metabolism for Cancer Therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safrhansova, L.; Hlozkova, K.; Starkova, J. Targeting Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 373, 37–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.-H.; Coloff, J.L. The Diverse Functions of Non-Essential Amino Acids in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; van der Meer, L.T.; van Leeuwen, F.N. Amino Acid Depletion Therapies: Starving Cancer Cells to Death. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernieri, C.; Casola, S.; Foiani, M.; Pietrantonio, F.; de Braud, F.; Longo, V. Targeting Cancer Metabolism: Dietary and Pharmacologic Interventions. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1315–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pui, C.H.; Mullighan, C.G.; Evans, W.E.; Relling, M.V. Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Where Are We Going and How Do We Get There? Blood 2012, 120, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajan, M.; Vousden, K.H. Dietary Approaches to Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly-Schoonen, J.; Biamonte, S.F.; Danowski, L.; Montrose, D.C. Modifying Dietary Amino Acids in Cancer Patients. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 373, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alonso, J.J.; Guillén-Mancina, E.; Calderón-Montaño, J.M.; Jiménez-González, V.; Díaz-Ortega, P.; Burgos-Morón, E.; López-Lázaro, M. Artificial Diets Based on Selective Amino Acid Restriction versus Capecitabine in Mice with Metastatic Colon Cancer. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Montaño, J.M.; Guillén-Mancina, E.; Jiménez-Alonso, J.J.; Jiménez-González, V.; Burgos-Morón, E.; Mate, A.; Pérez-Guerrero, M.C.; López-Lázaro, M. Manipulation of Amino Acid Levels with Artificial Diets Induces a Marked Anticancer Activity in Mice with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2022, 2022, 16132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, M.; Ogura, Y.; Monno, I.; Koya, D. The Impact of Dietary Protein Intake on Longevity and Metabolic Health. EBioMedicine 2019, 43, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, H.; Suarez, J.A.; Longo, V.D. Protein and Amino Acid Restriction, Aging and Disease: From Yeast to Humans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ren, W.; Huang, X.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. Protein Restriction and Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer 2018, 1869, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Suarez, J.A.; Brandhorst, S.; Balasubramanian, P.; Cheng, C.-W.; Madia, F.; Fontana, L.; Mirisola, M.G.; Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Wan, J.; et al. Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhorst, S.; Wei, M.; Hwang, S.; Morgan, T.E.; Longo, V.D. Short-Term Calorie and Protein Restriction Provide Partial Protection from Chemotoxicity but Do Not Delay Glioma Progression. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Patiño, C.; Bossowski, J.P.; De Donatis, G.M.; Mondragón, L.; Villa, E.; Aira, L.E.; Chiche, J.; Mhaidly, R.; Lebeaupin, C.; Marchetti, S.; et al. Low-Protein Diet Induces IRE1α-Dependent Anticancer Immunosurveillance. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orillion, A.; Damayanti, N.P.; Shen, L.; Adelaiye-Ogala, R.; Affronti, H.; Elbanna, M.; Chintala, S.; Ciesielski, M.; Fontana, L.; Kao, C.; et al. Dietary Protein Restriction Reprograms Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Enhances Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 6383–6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.; Adelaiye, R.M.; Rastelli, A.L.; Miles, K.M.; Ciamporcero, E.; Longo, V.D.; Nguyen, H.; Vessella, R.; Pili, R. Dietary Protein Restriction Inhibits Tumor Growth in Human Xenograft Models of Prostate and Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.A.A.; Koshiyama, M.; Matsumura, N.; Abiko, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hamanishi, J.; Baba, T.; Kharma, B.; Mohamed, I.H.; Ameen, M.M.; et al. The Effect of the Type of Dietary Protein on the Development of Ovarian Cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 23987–23999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G. Amino Acids: Metabolism, Functions, and Nutrition. Amino Acids 2009, 37, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Cho, Y. ra; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.; Nam, H.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Son, J. Branched-Chain Amino Acids Sustain Pancreatic Cancer Growth by Regulating Lipid Metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, T.; Birnbaum, S.M.; Winitz, M.; Greenstein, J.P. Quantitative Nutritional Studies with Water-Soluble, Chemically Defined Diets. VIII. The Forced Feeding of Diets Each Lacking in One Essential Amino Acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959, 81, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuer, R.C. Effect of Essential Amino Acid Restriction on the Growth of Female C57BL Mice and Their Implanted BW10232 Adenocarcinomas. J. Nutr. 1971, 101, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J.-H.; Zoncu, R.; Kim, D.; Sabatini, D.M. Defective Regulation of Autophagy upon Leucine Deprivation Reveals a Targetable Liability of Human Melanoma Cells in Vitro and in Vivo. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Wang, C.; Yin, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, S.; Fang, J.; Guo, F. Leucine Deprivation Inhibits Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis of Human Breast Cancer Cells via Fatty Acid Synthase. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 63679–63689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönjes, M.; Barbus, S.; Park, Y.J.; Wang, W.; Schlotter, M.; Lindroth, A.M.; Pleier, S.V.; Bai, A.H.C.; Karra, D.; Piro, R.M.; et al. BCAT1 Promotes Cell Proliferation through Amino Acid Catabolism in Gliomas Carrying Wild-Type IDH1. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Faddaoui, A.; Bachvarova, M.; Plante, M.; Gregoire, J.; Renaud, M.C.; Sebastianelli, A.; Guillemette, C.; Gobeil, S.; Macdonald, E.; et al. BCAT1 Expression Associates with Ovarian Cancer Progression: Possible Implications in Altered Disease Metabolism. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 31522–31543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.H.; Hu, W.J.; Chen, B.C.; Grahn, T.H.M.; Zhao, Y.R.; Bao, H.L.; Zhu, Y.F.; Zhang, Q.Y. BCAT1, a Key Prognostic Predictor of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Promotes Cell Proliferation and Induces Chemoresistance to Cisplatin. Liver Int. 2016, 36, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, A.; Tsunoda, M.; Konuma, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Nagy, T.; Glushka, J.; Tayyari, F.; McSkimming, D.; Kannan, N.; Tojo, A.; et al. Cancer Progression by Reprogrammed BCAA Metabolism in Myeloid Leukaemia. Nature 2017, 545, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Achreja, A.; Meurs, N.; Animasahun, O.; Owen, S.; Mittal, A.; Parikh, P.; Lo, T.W.; Franco-Barraza, J.; Shi, J.; et al. Tumour-Reprogrammed Stromal BCAT1 Fuels Branched-Chain Ketoacid Dependency in Stromal-Rich PDAC Tumours. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Han, J. Branched-Chain Amino Acid Transaminase 1 (BCAT1) Promotes the Growth of Breast Cancer Cells through Improving MTOR-Mediated Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 486, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.A.; Lashinger, L.M.; Rasmussen, A.J.; Hursting, S.D. Leucine Supplementation Differentially Enhances Pancreatic Cancer Growth in Lean and Overweight Mice. Cancer Metab. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, P.J.; Smith, K.; Etheridge, T.; Rankin, D.; Rennie, M.J. Distinct Anabolic Signalling Responses to Amino Acids in C2C12 Skeletal Muscle Cells. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.M.M.; Jeong, S.J.J.; Park, M.C.C.; Kim, G.; Kwon, N.H.H.; Kim, H.K.K.; Ha, S.H.H.; Ryu, S.H.H.; Kim, S. Leucyl-TRNA Synthetase Is an Intracellular Leucine Sensor for the MTORC1-Signaling Pathway. Cell 2012, 149, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahara, T.; Amemiya, Y.; Sugiyama, R.; Maki, M.; Shibata, H. Amino Acid-Dependent Control of MTORC1 Signaling: A Variety of Regulatory Modes. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, Y.; Hatazawa, Y.; Uchitomi, R.; Yoshimura, R.; Miura, S. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Function by Amino Acids. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro, M. Selective Amino Acid Restriction Therapy (SAART): A Non- Pharmacological Strategy against All Types of Cancer Cells. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudry, A.G.; Law, M.L. Leucine Supplementation in Cancer Cachexia: Mechanisms and a Review of the Pre-Clinical Literature. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracos, V.E.; Martin, L.; Korc, M.; Guttridge, D.C.; Fearon, K.C.H. Cancer-Associated Cachexia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. MTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburn, S.C.; Vann, C.G.; Church, D.D.; Ferrando, A.A.; Roberts, M.D. Proteasome- and Calpain-Mediated Proteolysis, but Not Autophagy, Is Required for Leucine-Induced Protein Synthesis in C2C12 Myotubes. Physiologia 2021, 1, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.R.; Chiocchetti, G. de M. e; Oroy, L.; Vieira, W.F.; Busanello, E.N.B.; Marques, A.C.; Salgado, C. de M.; de Oliveira, A.L.R.; Vieira, A.S.; Suarez, P.S.; et al. Leucine-Rich Diet Improved Muscle Function in Cachectic Walker 256 Tumour-Bearing Wistar Rats. Cells 2021, 10, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, B.; Oliveira, A.; Viana, L.R.; Lopes-Aguiar, L.; Canevarolo, R.; Colombera, M.C.; Valentim, R.R.; Garcia-Fóssa, F.; de Sousa, L.M.; Castelucci, B.G.; et al. Leucine-Rich Diet Modulates the Metabolomic and Proteomic Profile of Skeletal Muscle during Cancer Cachexia. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toneto, A.T.; Ferreira Ramos, L.A.; Salomão, E.M.; Tomasin, R.; Aereas, M.A.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. Nutritional Leucine Supplementation Attenuates Cardiac Failure in Tumour-Bearing Cachectic Animals. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventrucci, G.; Mello, M.A.R.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. Proteasome Activity Is Altered in Skeletal Muscle Tissue of Tumour-Bearing Rats Fed a Leucine-Rich Diet. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2004, 11, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomão, E.M.; Toneto, A.T.; Silva, G.O.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. Physical Exercise and a Leucine-Rich Diet Modulate the Muscle Protein Metabolism in Walker Tumor-Bearing Rats. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomão, E.M.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. Light Aerobic Physical Exercise in Combination with Leucine and/or Glutamine-Rich Diet Can Improve the Body Composition and Muscle Protein Metabolism in Young Tumor-Bearing Rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 68, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C.; Ventrucci, G.; Toledo, M.T.; Cury, L.; Cooper, J.C. A Leucine-Supplemented Diet Improved Protein Content of Skeletal Muscle in Young Tumor-Bearing Rats. Brazilian J. Med. Biol. Res. 2003, 36, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, B.; Oliveira, A.; Gomes-Marcondes, M.C.C. L-Leucine Dietary Supplementation Modulates Muscle Protein Degradation and Increases pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Tumour-Bearing Rats. Cytokine 2017, 96, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.J.; Van Helvoort, A.; Kegler, D.; Argilès, J.M.; Luiking, Y.C.; Laviano, A.; Van Bergenhenegouwen, J.; Deutz, N.E.P.; Haagsman, H.P.; Gorselink, M.; et al. Dose-Dependent Effects of Leucine Supplementation on Preservation of Muscle Mass in Cancer Cachectic Mice. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Norren, K.; Kegler, D.; Argilés, J.M.; Luiking, Y.; Gorselink, M.; Laviano, A.; Arts, K.; Faber, J.; Jansen, H.; Van Der Beek, E.M.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with a Specific Combination of High Protein, Leucine, and Fish Oil Improves Muscle Function and Daily Activity in Tumour-Bearing Cachectic Mice. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Mao, X.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; Yang, Q. Isoleucine Plays an Important Role for Maintaining Immune Function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2019, 20, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Yu, J.; Guo, Y.; Deng, J.; Li, K.; Du, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Sheng, H.; Guo, F. Effects of Individual Branched-Chain Amino Acids Deprivation on Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose Metabolism in Mice. Metabolism. 2014, 63, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.D. A Nutritional Disease of Childhood Associated with a Maize Diet. Arch. Dis. Child. 1983, 58, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocher, R.A. Effects of a Low Lysine Diet on the Growth of Spontaneous Mammary Tumors in Mice and on the N2 Balance in Man. Cancer Res. 1944, 4, 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- van Spronsen, F.J.; Blau, N.; Harding, C.; Burlina, A.; Longo, N.; Bosch, A.M. Phenylketonuria. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, W.L.; Elliott, J.A. Fluorophenylalanine Inhibition of Tumors in Mice on a Phenylalanine-Deficient Diet. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demopoulos, H.B. Effects of Low Phenylalanine-Tyrosine Diets on S91 Mouse Melanomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1966, 37, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounous, G.; Kongshavn, P.A.L. The Effect of Dietary Amino Acids on the Growth of Tumors. Experientia 1981, 37, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, R.M.; Starkey, J.R.; Meadows, G.G. Dietary Restriction of Tyrosine and Phenylalanine: Inhibition of Metastasis of Three Rodent Tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1987, 78, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, C.A.; Meadows, G.G.; Abdallah, R.M. Specificity of the Suppression of Metastatic Phenotype by Tyrosine and Phenylalanine Restriction. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 1990, 8, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, C.A.; Thrall, B.D.; Raha, G.; Meadows, G.G. Tyrosine and Phenylalanine Restriction Sensitizes Adriamycin-Resistant P388 Leukemia Cells to Adriamycin. Nutr. Cancer 1996, 25, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenkott, C.E.; Huijzer, J.C.; Cardeiro, D.J.; Elstad, C.A.; Meadows, G.G. Attachment, Invasion, Chemotaxis, and Proteinase Expression of B16-BL6 Melanoma Cells Exhibiting a Low Metastatic Phenotype after Exposure to Dietary Restriction of Tyrosine and Phenylalanine. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 1996, 14, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelayo, B.A.; Fu, Y.M.; Meadows, G.G. Inhibition of B16BL6 Melanoma Invasion by Tyrosine and Phenylalanine Deprivation Is Associated with Decreased Secretion of Plasminogen Activators and Increased Plasminogen Activator Inhibitors. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 1999, 17, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.M.; Yu, Z.X.; Li, Y.Q.; Ge, X.; Sanchez, P.J.; Fu, X.; Meadows, G.G. Specific Amino Acid Dependency Regulates Invasiveness and Viability of Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2003, 45, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.M.; Zhang, H.; Ding, M.; Li, Y.Q.; Fu, X.; Yu, Z.X.; Meadows, G.G. Specific Amino Acid Restriction Inhibits Attachment and Spreading of Human Melanoma via Modulation of the Integrin/Focal Adhesion Kinase Pathway and Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2005, 21, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.M.; Zhang, H.; Ding, M.; Li, Y.Q.; Fu, X.; Yu, Z.X.; Meadows, G.G. Selective Amino Acid Restriction Targets Mitochondria to Induce Apoptosis of Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006, 209, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, N.P.; Liu, H.; Meadows, G.G. PPAR-γ Ligands and Amino Acid Deprivation Promote Apoptosis of Melanoma, Prostate, and Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Lett. 2006, 236, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Fu, Y.-M.; Meadows, G.G. Differential Effects of Specific Amino Acid Restriction on Glucose Metabolism, Reduction/Oxidation Status and Mitochondrial Damage in DU145 and PC3 Prostate Cancer Cells. Oncol. Lett. 2011, 2, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demopoulos, H.B. Effects of Reducing the Phenylalanine-Tyrosine Intake of Patients with Advanced Malignant Melanoma. Cancer 1966, 19, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorincz, A.B.; Kuttner, R.E. Response of Malignancy to Phenylalanine Restriction. A Preliminary Report on a New Concept of Managing Malignant Disease. Nebr. State Med. J. 1965, 50, 609–617. [Google Scholar]

- Edmund, J.; Jensen, O.A.; Egeberg, J. Reduced Intake of Phenylalanine and Tyrosine as Treatment of Choroidal Malignant Melanoma. Mod. Probl. Ophthalmol. 1974, 12, 504–509. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, D.H.; Stockton, L.H.; Bleier, J.C.; Acosta, P.B.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Nixon, D.W. The Effect of a Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Restricted Diet on Elemental Balance Studies and Plasma Aminograms of Patients with Disseminated Malignant Melanoma. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 41, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, M.N.; Campbell, I.T.; Howell, A.; Thatcher, N. Acceptability and Tolerance of a Low Tyrosine and Phenylalanine Diet in Patients with Advanced Cancer - a Pilot Study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2002, 15, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosnan, M.E.; Brosnan, J.T. Histidine Metabolism and Function. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2570S–2575S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froldi, F.; Pachnis, P.; Szuperák, M.; Costas, O.; Fernando, T.; Gould, A.P.; Cheng, L.Y. Histidine Is Selectively Required for the Growth of Myc-dependent Dedifferentiation Tumours in the Drosophila CNS. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e99895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanarek, N.; Keys, H.R.; Cantor, J.R.; Lewis, C.A.; Chan, S.H.; Kunchok, T.; Abu-Remaileh, M.; Freinkman, E.; Schweitzer, L.D.; Sabatini, D.M. Histidine Catabolism Is a Major Determinant of Methotrexate Sensitivity. Nature 2018, 559, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opitz, C.A.; Somarribas Patterson, L.F.; Mohapatra, S.R.; Dewi, D.L.; Sadik, A.; Platten, M.; Trump, S. The Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Tryptophan Catabolism in Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Tomek, P. Tryptophan: A Rheostat of Cancer Immune Escape Mediated by Immunosuppressive Enzymes IDO1 and TDO. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, S.K.; Conrad, N.C.; Olson, R.E.; Kohrs, M.B.; Ghosh, L. Amino Acid-Restricted Diets in the Treatment of Mammary Adenocarcinoma in Mice. J. Nutr. 1988, 118, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenk, M.; Scheler, M.; Koch, S.; Neumann, J.; Takikawa, O.; Häcker, G.; Bieber, T.; von Bubnoff, D. Tryptophan Deprivation Induces Inhibitory Receptors ILT3 and ILT4 on Dendritic Cells Favoring the Induction of Human CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3 + T Regulatory Cells. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallarino, F.; Grohmann, U.; You, S.; McGrath, B.C.; Cavener, D.R.; Vacca, C.; Orabona, C.; Bianchi, R.; Belladonna, M.L.; Volpi, C.; et al. The Combined Effects of Tryptophan Starvation and Tryptophan Catabolites Down-Regulate T Cell Receptor ζ-Chain and Induce a Regulatory Phenotype in Naive T Cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 6752–6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramme, F.; Crosignani, S.; Frederix, K.; Hoffmann, D.; Pilotte, L.; Stroobant, V.; Preillon, J.; Driessens, G.; van den Eynde, B.J. Inhibition of Tryptophan-Dioxygenase Activity Increases the Antitumor Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, J.; Däbritz, J.; Wirthgen, E. Limitations and Off-Target Effects of Tryptophan-Related IDO Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, G.V.; Dummer, R.; Hamid, O.; Gajewski, T.F.; Caglevic, C.; Dalle, S.; Arance, A.; Carlino, M.S.; Grob, J.J.; Kim, T.M.; et al. Epacadostat plus Pembrolizumab versus Placebo plus Pembrolizumab in Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma (ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252): A Phase 3, Randomised, Double-Blind Study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mato, J.M.; Martínez-Chantar, M.L.; Lu, S.C. S-Adenosylmethionine Metabolism and Liver Disease. Ann. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.; Birsoy, K. The Transsulfuration Pathway Makes, the Tumor Takes. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshiya, Y.; Kubota, T.; Matsuzaki, S.W.; Kitajima, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Methionine Starvation Modulates the Efficacy of Cisplatin on Human Breast Cancer in Nude Mice. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 3515–3518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoshiya, Y.; Kubota, T.; Inada, T.; Kitajima, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Methionine-Depletion Modulates the Efficacy of 5-Fluorouracil in Human Gastric Cancer in Nude Mice. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17, 4371–4375. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Lishko, V.K.; Herrera, H.; Groce, A.; Kubota, T.; Hoffman, R.M. Therapeutic Tumor-Specific Cell Cycle Block Induced by Methionine Starvation in Vivo. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 5676–5679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, E.; Jang, Y.J.; Son, J.E.; Kwon, J.Y.; Lim, T.; Kim, S.; Park, J.H.Y.; Kim, J.-E.; et al. Methionine Deprivation Suppresses Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Metastasis in Vitro and in Vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 67223–67234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strekalova, E.; Malin, D.; Good, D.M.; Cryns, V.L. Methionine Deprivation Induces a Targetable Vulnerability in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells by Enhancing TRAIL Receptor-2 Expression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2780–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, D.; Lee, Y.; Chepikova, O.; Strekalova, E.; Carlson, A.; Cryns, V.L. Methionine Restriction Exposes a Targetable Redox Vulnerability of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells by Inducing Thioredoxin Reductase. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 190, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Yin, F.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, B.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. Methionine and Cystine Double Deprivation Stress Suppresses Glioma Proliferation via Inducing ROS/Autophagy. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 232, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R.; Cooper, T.K.; Rogers, C.J.; Sinha, I.; Turbitt, W.J.; Calcagnotto, A.; Perrone, C.E.; Richie, J.P. Dietary Methionine Restriction Inhibits Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia in TRAMP Mice. Prostate 2014, 74, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Kang, K.; Williams, J.G.; Tong, L.; Liu, J.; Ji, M.; Deterding, L.J.; Tong, X.; et al. HNF4α Regulates Sulfur Amino Acid Metabolism and Confers Sensitivity to Methionine Restriction in Liver Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Sanderson, S.M.; Dai, Z.; Reid, M.A.; Cooper, D.E.; Lu, M.; Richie, J.P.; Ciccarella, A.; Calcagnotto, A.; Mikhael, P.G.; et al. Dietary Methionine Influences Therapy in Mouse Cancer Models and Alters Human Metabolism. Nature 2019, 572, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hens, J.R.; Sinha, I.; Perodin, F.; Cooper, T.; Sinha, R.; Plummer, J.; Perrone, C.E.; Orentreich, D. Methionine-Restricted Diet Inhibits Growth of MCF10AT1-Derived Mammary Tumors by Increasing Cell Cycle Inhibitors in Athymic Nude Mice. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komninou, D.; Leutzinger, Y.; Reddy, B.S.; Richie, J.P. Methionine Restriction Inhibits Colon Carcinogenesis. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 54, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J.L.; Wu, D.Z.; Yuan, Y.W.; Xin, L. Methionine Restriction Enhances the Chemotherapeutic Sensitivity of Colorectal Cancer Stem Cells by MiR-320d/c-Myc Axis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tan, Y.-T.; Chen, Y.-X.; Zheng, X.-J.; Wang, W.; Liao, K.; Mo, H.-Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; Piao, H.-L.; et al. Methionine Deficiency Facilitates Antitumour Immunity by Altering m 6 A Methylation of Immune Checkpoint Transcripts. Gut 2023, 72, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alonso, J.J.; Guillén-Mancina, E.; Calderón-Montaño, J.M.; Jiménez-González, V.; Díaz-Ortega, P.; Burgos-Morón, E.; López-Lázaro, M. Artificial Diets with Altered Levels of Sulfur Amino Acids Induce Anticancer Activity in Mice with Metastatic Colon Cancer, Ovarian Cancer and Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyayula, P.S.; Higgins, D.M.; Mela, A.; Banu, M.; Dovas, A.; Zandkarimi, F.; Patel, P.; Mahajan, A.; Humala, N.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; et al. Dietary Restriction of Cysteine and Methionine Sensitizes Gliomas to Ferroptosis and Induces Alterations in Energetic Metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goseki, N.; Endo, M.; Onodera, T.; Kosaki, G. Anti-Tumor Effect of L-Methionine-Deprived Total Parenteral Nutrition with 5-Fluorouracil Administration on Yoshida Sarcoma-Bearing Rats. Ann. Surg. 1991, 214, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goseki, N.; Nagahama, T.; Maruyama, M.; Endo, M. Enhanced Anticancer Effect of Vincristine with Methionine Infusion after Methionine-Depleting Total Parenteral Nutrition in Tumor-Bearing Rats. Japanese J. Cancer Res. 1996, 87, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Tan, Y.; Kubota, T.; Moossa, A.R.; Hoffman, R.M. Methionine Depletion Modulates the Antitumor and Antimetastatic Efficacy of Ethionine. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 2719–2723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.B.; Cao, W.X.; Yin, H.R.; Lin, Y.Z.; Ye, S.H. Influence of L-Methionine-Deprived Total Parenteral Nutrition with 5-Fluorouracil on Gastric Cancer and Host Metabolism. World J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 7, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshiya, Y.; Guo, H.; Kubota, T.; Inada, T.; Asanuma, F.; Yamada, Y.; Koh, J.I.; Kitajima, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Human Tumors Are Methionine Dependent in Vivo. Anticancer Res. 1995, 15, 717–718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.A.; Buehner, G.; Chang, Y.; Harper, J.M.; Sigler, R.; Smith-Wheelock, M. Methionine-Deficient Diet Extends Mouse Lifespan, Slows Immune and Lens Aging, Alters Glucose, T4, IGF-I and Insulin Levels, and Increases Hepatocyte MIF Levels and Stress Resistance. Aging Cell 2005, 4, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, W.O.; Margolies, N.S.; Anthony, T.G. Dietary Sulfur Amino Acid Restriction and the Integrated Stress Response: Mechanistic Insights. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, L.A.; Wanders, D.; Stone, K.P.; Pierse, A.; Gettys, T.W. Concentration-Dependent Linkage of Dietary Methionine Restriction to the Components of Its Metabolic Phenotype. Obesity 2017, 25, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breillout, F.; Hadida, F.; Echinard-Garin, P.; Lascaux, V.; Poupon, M.F. Decreased Rat Rhabdomyosarcoma Pulmonary Metastases in Response to a Low Methionine Diet. Anticancer Res. 1987, 7, 861–868. [Google Scholar]

- Casero, R.A.; Murray Stewart, T.; Pegg, A.E. Polyamine Metabolism and Cancer: Treatments, Challenges and Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.; Gomez, J.; Torres, M.L.; Naudi, A.; Mota-Martorell, N.; Pamplona, R.; Barja, G. Cysteine Dietary Supplementation Reverses the Decrease in Mitochondrial ROS Production at Complex I Induced by Methionine Restriction. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2015, 47, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshorbagy, A.K.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Mattocks, D.A.L.; Plummer, J.D.; Smith, A.D.; Drevon, C.A.; Refsum, H.; Perrone, C.E. Cysteine Supplementation Reverses Methionine Restriction Effects on Rat Adiposity: Significance of Stearoyl-Coenzyme a Desaturase. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voegtlin, C.; Johnson, J.M.; Thompson, J.W. Glutathione and Malignant Growth. Public Heal. Reports 1936, 51, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavuoto, P.; Fenech, M.F. A Review of Methionine Dependency and the Role of Methionine Restriction in Cancer Growth Control and Life-Span Extension. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2012, 38, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, B.C.; Clark, B.R.; Hardy, D.N.; Halpern, R.M.; Smith, R.A. The Effect of Replacement of Methionine by Homocystine on Survival of Malignant and Normal Adult Mammalian Cells in Culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1974, 71, 1133–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreis, W.; Goodenow, M. Methionine Requirement and Replacement by Homocysteine in Tissue Cultures of Selected Rodent and Human Malignant and Normal Cells. Cancer Res. 1978, 38, 2259–2262. [Google Scholar]

- Bertino, J.R.; Waud, W.R.; Parker, W.B.; Lubin, M. Targeting Tumors That Lack Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase (MTAP) Activity. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Hoffman, R.M.; Bertino, J.R. Exploiting Methionine Restriction for Cancer Treatment. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 154, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, E.C.; Ghisolfi, L.; Geck, R.C.; Asara, J.M.; Toker, A. Oncogenic PI3K Promotes Methionine Dependency in Breast Cancer Cells through the Cystine-Glutamate Antiporter XCT. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Li, W.; Kremer, D.M.; Sajjakulnukit, P.; Li, S.; Crespo, J.; Nwosu, Z.C.; Zhang, L.; Czerwonka, A.; Pawłowska, A.; et al. Cancer SLC43A2 Alters T Cell Methionine Metabolism and Histone Methylation. Nature 2020, 585, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goseki, N.; Yamazaki, S.; Shimojyu, K.; Kando, F.; Maruyama, M.; Endo, M.; Koike, M.; Takahashi, H. Synergistic Effect of Methionine-Depleting Total Parenteral Nutrition with 5-Fluorouracil on Human Gastric Cancer: A Randomized, Prospective Clinical Trial. Japanese J. Cancer Res. 1995, 86, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epner, D.E.; Morrow, S.; Wilcox, M.; Houghton, J.L. Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Indexes in Adults with Metastatic Cancer on a Phase I Clinical Trial of Dietary Methionine Restriction. Nutr. Cancer 2002, 42, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thivat, E.; Durando, X.; Demidem, A.; Farges, M.C.; Rapp, M.; Cellarier, E.; Guenin, S.; D’Incan, M.; Vasson, M.P.; Chollet, P. A Methionine-Free Diet Associated with Nitrosourea Treatment down-Regulates Methylguanine-DNA Methyl Transferase Activity in Patients with Metastatic Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 2779–2783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thivat, E.; Farges, M.-C.; Bacin, F.; D’Incan, M.; Mouret-Reynier, M.-A.; Cellarier, E.; Madelmont, J.-C.; Vasson, M.-P.; Chollet, P.; Durando, X. Phase II Trial of the Association of a Methionine-Free Diet with Cystemustine Therapy in Melanoma and Glioma. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 5235–5240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durando, X.; Farges, M.-C.; Buc, E.; Abrial, C.; Petorin-Lesens, C.; Gillet, B.; Vasson, M.-P.; Pezet, D.; Chollet, P.; Thivat, E. Dietary Methionine Restriction with FOLFOX Regimen as First Line Therapy of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Feasibility Study. Oncology 2010, 78, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Xu, M.; Tan, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, X.; Saikawa, Y.; Nagahama, T.; Sun, X.; Lenz, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Overexpression and Large-Scale Production of Recombinant L-Methionine-α-Deamino-γ-Mercaptomethane-Lyase for Novel Anticancer Therapy. Protein Expr. Purif. 1997, 9, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Mingxu, X.U.; Guo, H.; Sun, X.; Kubota, T.; Hoffman, R.M. Anticancer Efficacy of Methioninase in Vivo. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 3931–3936. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Sun, X.; Xu, M.; Tan, X.; Sasson, A.; Rashidi, B.; Han, Q.; Tan, X.; Wang, X.; An, Z.; et al. Efficacy of Recombinant Methioninase in Combination with Cisplatin on Human Colon Tumors in Nude Mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2157–2163. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, T.; Wada, T.; Uchida, N.; Maki, H.; Yoshida, H.; Ide, N.; Kasai, H.; Hojo, K.; Shono, K.; Maekawa, R.; et al. Anticancer Efficacy in Vivo and in Vitro, Synergy with 5-Fluorouracil, and Safety of Recombinant Methioninase. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 2583–2587. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinakis, D.M.; Hoffman, R.M.; Frenkel, E.P.; Wick, J.B.; Han, Q.; Xu, M.; Tan, Y.; Schold, S.C. Synergy between Methionine Stress and Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Brain Tumor Xenografts in Athymic Mice. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4017–4023. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, K.; Igarashi, K.; Li, S.; Han, Q.; Tan, Y.; Kiyuna, T.; Miyake, K.; Murakami, T.; Chmielowski, B.; Nelson, S.D.; et al. Combination Treatment with Recombinant Methioninase Enables Temozolomide to Arrest a BRAF V600E Melanoma in a Patientderived Orthotopic Xenograft (PDOX) Mouse Model. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 85516–85525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Li, S.; Han, Q.; Tan, Y.; Murakami, T.; Kiyuna, T.; Miyake, K.; Miyake, M.; Singh, A.S.; et al. Recombinant Methioninase in Combination with Doxorubicin (DOX) Overcomes First-Line DOX Resistance in a Patient-Derived Orthotopic Xenograft Nude-Mouse Model of Undifferentiated Spindle-Cell Sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2018, 417, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yoshioka, T.; Li, B.; Lu, Q.; Li, S.; Sun, X.; Tan, Y.; Yagi, S.; Frenkel, E.P.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, Methionine Depletion, and Antigenicity of Recombinant Methioninase in Primates. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, Q.; Xu, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Takakura, T.; Takimoto, A.; Yoshioka, T.; Lian, C.; Chen, C.; et al. PEGylation Confers Greatly Extended Half-Life and Attenuated Immunogenicity to Recombinant Methioninase in Primates. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 6673–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T.; Kawaguchi, K.; Miyake, K.; Han, Q.; Tan, Y.; Oshiro, H.; Sugisawa, N.; Zhang, Z.; Razmjooei, S.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Oral Recombinant Methioninase Combined with Caffeine and Doxorubicin Induced Regression of a Doxorubicin-Resistant Synovial Sarcoma in a PDOX Mouse Model. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 5639–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, K.; Miyake, K.; Han, Q.; Li, S.; Tan, Y.; Igarashi, K.; Kiyuna, T.; Miyake, M.; Higuchi, T.; Oshiro, H.; et al. Oral Recombinant Methioninase (o-RMETase) Is Superior to Injectable RMETase and Overcomes Acquired Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018, 432, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T.; Sugisawa, N.; Yamamoto, J.; Oshiro, H.; Han, Q.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Kimura, H.; Miwa, S.; Igarashi, K.; et al. The Combination of Oral-Recombinant Methioninase and Azacitidine Arrests a Chemotherapy-Resistant Osteosarcoma Patient-Derived Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Model. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2020, 85, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, J.; Miyake, K.; Han, Q.; Tan, Y.; Inubushi, S.; Sugisawa, N.; Higuchi, T.; Tashiro, Y.; Nishino, H.; Homma, Y.; et al. Oral Recombinant Methioninase Increases TRAIL Receptor-2 Expression to Regress Pancreatic Cancer in Combination with Agonist Tigatuzumab in an Orthotopic Mouse Model. Cancer Lett. 2020, 492, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Kiyuna, T.; Miyake, K.; Miyaki, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Kimura, H.; Miwa, S.; Higuchi, T.; et al. Metabolic Targeting with Recombinant Methioninase Combined with Palbociclib Regresses a Doxorubicin-Resistant Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 506, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugisawa, N.; Hamada, K.; Qinghong, H.A.N.; Yamamoto, J.; Yu, S.U.N.; Nishino, H.; Kawaguchi, K.; Bouvet, M.; Unno, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Adjuvant Oral Recombinant Methioninase Inhibits Lung Metastasis in a Surgical Breast-Cancer Orthotopic Syngeneic Model. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 4869–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, T.; Han, Q.; Miyake, K.; Oshiro, H.; Sugisawa, N.; Tan, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Kimura, H.; Miwa, S.; et al. Combination of Oral Recombinant Methioninase and Decitabine Arrests a Chemotherapy-Resistant Undifferentiated Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Patient-Derived Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 523, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, Y.; Tome, Y.; Qinghong, H.A.N.; Yamamoto, J.; Hamada, K.; Masaki, N.; Kubota, Y.; Bouvet, M.; Nishida, K.; Hoffman, R.M. Oral-Recombinant Methioninase Converts an Osteosarcoma from Methotrexate-Resistant to -Sensitive in a Patient-Derived Orthotopic-Xenograft (PDOX) Mouse Model. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, E.; Paley, O.; Hu, J.; Ekerdt, B.; Cheung, N.K.; Georgiou, G. De Novo Engineering of a Human Cystathionine-γ-Lyase for Systemic l-Methionine Depletion Cancer Therapy. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1822–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.C.; Saha, A.; Yan, W.; Garrison, K.; Lamb, C.; Pandey, R.; Irani, S.; Lodi, A.; Lu, X.; Tiziani, S.; et al. Enzyme-Mediated Depletion of Serum L-Met Abrogates Prostate Cancer Growth via Multiple Mechanisms without Evidence of Systemic Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 13000–13011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zavala, J.; Mingxu, X.U.; Zavala, J.; Hoffman, R.M. Serum Methionine Depletion without Side Effects by Methioninase in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 3937–3942. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Zavala, J.; Han, Q.; Xu, M.; Sun, X.; Tan, X.; Tan, X.; Magana, R.; Geller, J.; Hoffman, R.M. Recombinant Methioninase Infusion Reduces the Biochemical Endpoint of Serum Methionine with Minimal Toxicity in High-Stage Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17, 3857–3860. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota, Y.; Han, Q.; Hamada, K.; Aoki, Y.; Masaki, N.; Obara, K.; Tsunoda, T.; Hoffman, R.M. Long-Term Stable Disease in a Rectal-Cancer Patient Treated by Methionine Restriction With Oral Recombinant Methioninase and a Low-Methionine Diet. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 3857–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Han, Q.; Hozumi, C.; Masaki, N.; Yamamoto, J.; Aoki, Y.; Tsunoda, T.; Hoffman, R.M. Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer Patient Treated With FOLFIRINOX Combined With Oral Methioninase: A Highly-Rare Case With Long-Term Stable Disease. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 2567–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.A.; DeNicola, G.M. The Non-Essential Amino Acid Cysteine Becomes Essential for Tumor Proliferation and Survival. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-F.; Klein Geltink, R.I.; Parker, S.J.; Sorensen, P.H. Transsulfuration, Minor Player or Crucial for Cysteine Homeostasis in Cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltorack, C.D.; Dixon, S.J. Understanding the Role of Cysteine in Ferroptosis: Progress & Paradoxes. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.S.; Treloar, A.E.; Inoue, S.; Sasaki, M.; Gorrini, C.; Lee, K.C.; Yung, K.Y.; Brenner, D.; Knobbe-Thomsen, C.B.; Cox, M.A.; et al. Glutathione and Thioredoxin Antioxidant Pathways Synergize to Drive Cancer Initiation and Progression. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HumanCyc HumanCyc: Encyclopedia of Human Genes and Metabolism. Available online: https://humancyc.org/ (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Zhang, T.; Bauer, C.; Newman, A.C.; Uribe, A.H.; Athineos, D.; Blyth, K.; Maddocks, O.D.K. Polyamine Pathway Activity Promotes Cysteine Essentiality in Cancer Cells. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 1062–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yeung, S.-C.J.; Liu, S.; Qdaisat, A.; Jiang, D.; Liu, W.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; et al. Cyst(e)Ine in Nutrition Formulation Promotes Colon Cancer Growth and Chemoresistance by Activating MTORC1 and Scavenging ROS. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodado, V.; Dowdy, T.; Lita, A.; Kramp, T.; Zhang, M.; Jung, J.; Dios-Esponera, A.; Zhang, L.; Herold-Mende, C.C.; Camphausen, K.; et al. Cysteine Is a Limiting Factor for Glioma Proliferation and Survival. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 1777–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Sinha, P.; Clements, V.K.; Rodriguez, P.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Inhibit T Cell Activation by Depleting Cystine and Cysteine. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, V.D.B.; Pereira, S.A.; Serpa, J.; Vicente, J.B. Cysteine Metabolic Circuitries: Druggable Targets in Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatae, R.; Chamoto, K.; Kim, Y.H.; Sonomura, K.; Taneishi, K.; Kawaguchi, S.; Yoshida, H.; Ozasa, H.; Sakamori, Y.; Akrami, M.; et al. Combination of Host Immune Metabolic Biomarkers for the PD-1 Blockade Cancer Immunotherapy. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Green, M.; Choi, J.E.; Gijón, M.; Kennedy, P.D.; Johnson, J.K.; Liao, P.; Lang, X.; Kryczek, I.; Sell, A.; et al. CD8+ T Cells Regulate Tumour Ferroptosis during Cancer Immunotherapy. Nature 2019, 569, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, S.L.; Saha, A.; Liu, J.; Tadi, S.; Tiziani, S.; Yan, W.; Triplett, K.; Lamb, C.; Alters, S.E.; Rowlinson, S.; et al. Systemic Depletion of L-Cyst(e)Ine with Cyst(e)Inase Increases Reactive Oxygen Species and Suppresses Tumor Growth. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kshattry, S.; Saha, A.; Gries, P.; Tiziani, S.; Stone, E.; Georgiou, G.; DiGiovanni, J. Enzyme-Mediated Depletion of l-Cyst(e)Ine Synergizes with Thioredoxin Reductase Inhibition for Suppression of Pancreatic Tumor Growth. npj Precis. Oncol. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.; Georgiou, G.; Stone, E.; Kidane, D.; DiGiovanni, J. Combinatorial Approaches to Enhance DNA Damage Following Enzyme-Mediated Depletion of L-Cys for Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badgley, M.A.; Kremer, D.M.; Maurer, H.C.; DelGiorno, K.E.; Lee, H.-J.; Purohit, V.; Sagalovskiy, I.R.; Ma, A.; Kapilian, J.; Firl, C.E.M.; et al. Cysteine Depletion Induces Pancreatic Tumor Ferroptosis in Mice. Science 2020, 368, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursaitidis, I.; Wang, X.; Crighton, T.; Labuschagne, C.; Mason, D.; Cramer, S.L.; Triplett, K.; Roy, R.; Pardo, O.E.; Seckl, M.J.; et al. Oncogene-Selective Sensitivity to Synchronous Cell Death Following Modulation of the Amino Acid Nutrient Cystine. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerimoglu, B.; Lamb, C.; McPherson, R.D.; Ergen, E.; Stone, E.M.; Ooi, A. Cyst(e)Inase-Rapamycin Combination Induces Ferroptosis in Both In Vitro and In Vivo Models of Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Sriramaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Cheah, J.H.; Clemons, P.A.; Shamji, A.F.; Clish, C.B.; et al. Regulation of Ferroptotic Cancer Cell Death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Jin, S.; Chen, Y.; Guo, R. Ferroptosis in Cancer Therapy: A Novel Approach to Reversing Drug Resistance. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Cystine Transporter SLC7A11/XCT in Cancer: Ferroptosis, Nutrient Dependency, and Cancer Therapy. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzardo, S.; Conti, L.; Rooke, R.; Ruiu, R.; Accart, N.; Bolli, E.; Arigoni, M.; Macagno, M.; Barrera, G.; Pizzimenti, S.; et al. Immunotargeting of Antigen XCT Attenuates Stem-like Cell Behavior and Metastatic Progression in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Luo, G.; Shi, X.; Long, Y.; Shen, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X. The Xc− Inhibitor Sulfasalazine Improves the Anti-Cancer Effect of Pharmacological Vitamin C in Prostate Cancer Cells via a Glutathione-Dependent Mechanism. Cell. Oncol. 2020, 43, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, K.; Lv, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Cheng, F.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Pei, H.; et al. Suppression of the SLC7A11/Glutathione Axis Causes Synthetic Lethality in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 1752–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, C.; Zhao, L. Erastin/Sorafenib Induces Cisplatin-Resistant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Ferroptosis through Inhibition of the Nrf2/XCT Pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miess, H.; Dankworth, B.; Gouw, A.M.; Rosenfeldt, M.; Schmitz, W.; Jiang, M.; Saunders, B.; Howell, M.; Downward, J.; Felsher, D.W.; et al. The Glutathione Redox System Is Essential to Prevent Ferroptosis Caused by Impaired Lipid Metabolism in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5435–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Shin, D.; Lee, J.; Jung, A.R.; Roh, J.L. CISD2 Inhibition Overcomes Resistance to Sulfasalazine-Induced Ferroptotic Cell Death in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018, 432, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.K.; Lee, S.; Kang, G.W.; Lee, Y.R.; Park, S.Y.; Song, I.S.; Yun, J.W.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.K.; Park, K.G. Macropinocytosis Is an Alternative Pathway of Cysteine Acquisition and Mitigates Sorafenib-Induced Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Stockwell, B.R. Unsolved Mysteries: How Does Lipid Peroxidation Cause Ferroptosis? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, H.; Daniels, J.D.; Zandkarimi, F.; Liu, H.; Brown, L.M.; Uchida, K.; O’Connor, O.A.; Stockwell, B.R. Imidazole Ketone Erastin Induces Ferroptosis and Slows Tumor Growth in a Mouse Lymphoma Model. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Swanda, R.V.; Nie, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Lee, H.; Lei, G.; Mao, C.; Koppula, P.; Cheng, W.; et al. MTORC1 Couples Cyst(e)Ine Availability with GPX4 Protein Synthesis and Ferroptosis Regulation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborzinia, H.; Flórez, A.F.; Kreth, S.; Brückner, L.M.; Yildiz, U.; Gartlgruber, M.; Odoni, D.I.; Poschet, G.; Garbowicz, K.; Shao, C.; et al. MYCN Mediates Cysteine Addiction and Sensitizes Neuroblastoma to Ferroptosis. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robe, P.A.; Martin, D.H.; Nguyen-Khac, M.T.; Artesi, M.; Deprez, M.; Albert, A.; Vanbelle, S.; Califice, S.; Bredel, M.; Bours, V. Early Termination of ISRCTN45828668, a Phase 1/2 Prospective, Randomized Study of Sulfasalazine for the Treatment of Progressing Malignant Gliomas in Adults. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitara, K.; Doi, T.; Nagano, O.; Imamura, C.K.; Ozeki, T.; Ishii, Y.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Takahashi, S.; Nakajima, T.E.; Hironaka, S.; et al. Dose-Escalation Study for the Targeting of CD44v+ Cancer Stem Cells by Sulfasalazine in Patients with Advanced Gastric Cancer (EPOC1205). Gastric Cancer 2017, 20, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitara, K.; Doi, T.; Nagano, O.; Fukutani, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Nomura, S.; Sato, A.; Kuwata, T.; Asai, K.; Einaga, Y.; et al. Phase 1 Study of Sulfasalazine and Cisplatin for Patients with CD44v-Positive Gastric Cancer Refractory to Cisplatin (EPOC1407). Gastric Cancer 2017, 20, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, S.; Wada, K.; Nagatani, K.; Otani, N.; Osada, H.; Nawashiro, H. Sulfasalazine and Temozolomide with Radiation Therapy for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. Neurol. India 2014, 62, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Vousden, K.H. Serine and One-Carbon Metabolism in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possemato, R.; Marks, K.M.; Shaul, Y.D.; Pacold, M.E.; Kim, D.; Birsoy, K.K.; Sethumadhavan, S.; Woo, H.-K.K.; Jang, H.G.; Jha, A.K.; et al. Functional Genomics Reveal That the Serine Synthesis Pathway Is Essential in Breast Cancer. Nature 2011, 476, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labuschagne, C.F.; van den Broek, N.J.F.; Mackay, G.M.; Vousden, K.H.; Maddocks, O.D.K. Serine, but Not Glycine, Supports One-Carbon Metabolism and Proliferation of Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddocks, O.D.K.K.; Athineos, D.; Cheung, E.C.; Lee, P.; Zhang, T.; Van Den Broek, N.J.F.F.; Mackay, G.M.; Labuschagne, C.F.; Gay, D.; Kruiswijk, F.; et al. Modulating the Therapeutic Response of Tumours to Dietary Serine and Glycine Starvation. Nature 2017, 544, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravel, S.-P.; Hulea, L.; Toban, N.; Birman, E.; Blouin, M.-J.; Zakikhani, M.; Zhao, Y.; Topisirovic, I.; St-Pierre, J.; Pollak, M. Serine Deprivation Enhances Antineoplastic Activity of Biguanides. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 7521–7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nyen, T.; Planque, M.; van Wagensveld, L.; Duarte, J.A.G.; Zaal, E.A.; Talebi, A.; Rossi, M.; Körner, P.R.; Rizzotto, L.; Moens, S.; et al. Serine Metabolism Remodeling after Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Identifies Vulnerabilities in a Subgroup of Resistant Ovarian Cancers. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.R.; Mattaini, K.R.; Dennstedt, E.A.; Nguyen, A.A.; Sivanand, S.; Reilly, M.F.; Meeth, K.; Muir, A.; Darnell, A.M.; Bosenberg, M.W.; et al. Increased Serine Synthesis Provides an Advantage for Tumors Arising in Tissues Where Serine Levels Are Limiting. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1410–1421.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, T.; Cordes, T.; Handzlik, M.K.; You, L.; Lim, E.W.; Gengatharan, J.; Pinto, A.F.M.; Badur, M.G.; Kolar, M.J.; Wallace, M.; et al. Serine Restriction Alters Sphingolipid Diversity to Constrain Tumour Growth. Nature 2020, 586, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.M.; Zhang, B.Z.; Jackson, T.D.; Ogunkola, M.O.; Nijagal, B.; Milne, J.V.; Sallman, D.A.; Ang, C.-S.; Nikolic, I.; Kearney, C.J.; et al. Eprenetapopt Triggers Ferroptosis, Inhibits NFS1 Cysteine Desulfurase, and Synergizes with Serine and Glycine Dietary Restriction. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddocks, O.D.K.K.; Berkers, C.R.; Mason, S.M.; Zheng, L.; Blyth, K.; Gottlieb, E.; Vousden, K.H. Serine Starvation Induces Stress and P53-Dependent Metabolic Remodelling in Cancer Cells. Nature 2013, 493, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humpton, T.J.; Hock, A.K.; Maddocks, O.D.K.; Vousden, K.H. P53-Mediated Adaptation to Serine Starvation Is Retained by a Common Tumour-Derived Mutant. Cancer Metab. 2018, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBoeuf, S.E.; Wu, W.L.; Karakousi, T.R.; Karadal, B.; Jackson, S.R.E.; Davidson, S.M.; Wong, K.K.; Koralov, S.B.; Sayin, V.I.; Papagiannakopoulos, T. Activation of Oxidative Stress Response in Cancer Generates a Druggable Dependency on Exogenous Non-Essential Amino Acids. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 339–350.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajan, M.; Hennequart, M.; Cheung, E.C.; Zani, F.; Hock, A.K.; Legrave, N.; Maddocks, O.D.K.; Ridgway, R.A.; Athineos, D.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; et al. Serine Synthesis Pathway Inhibition Cooperates with Dietary Serine and Glycine Limitation for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Uribe, A.H.; Papalazarou, V.; Newman, A.C.; Athineos, D.; Stevenson, K.; Sauvé, C.E.G.; Gao, Y.; Kim, J.K.; Del Latto, M.; et al. Sensitisation of Cancer Cells to Radiotherapy by Serine and Glycine Starvation. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Pardella, E.; Muccillo, L.; Leo, A.; Nesi, I.; Santi, A.; Parri, M.; Zhang, T.; Uribe, A.H.; Lottini, T.; et al. SHMT2-Mediated Mitochondrial Serine Metabolism Drives 5-FU Resistance by Fueling Nucleotide Biosynthesis. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polet, F.; Corbet, C.; Pinto, A.; Rubio, L.I.; Martherus, R.; Bol, V.; Drozak, X.; Grégoire, V.; Riant, O.; Feron, O. Reducing the Serine Availability Complements the Inhibition of the Glutamine Metabolism to Block Leukemia Cell Growth. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Lucas, A.; Lin, W.; Driscoll, P.C.; Legrave, N.; Novellasdemunt, L.; Xie, C.; Charles, M.; Wilson, Z.; Jones, N.P.; Rayport, S.; et al. Identifying Strategies to Target the Metabolic Flexibility of Tumours. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Nigdelioglu, R.; Meliton, A.Y.; Tian, Y.; Witt, L.J.; O’Leary, E.; Sun, K.A.; Woods, P.S.; Wu, D.; Ansbro, B.; et al. Inhibition of Phosphoglycerate Dehydrogenase Attenuates Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacold, M.E.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Chan, S.H.; Rohde, J.M.; Lewis, C.A.; Swier, L.J.Y.M.; Possemato, R.; Chen, W.W.; Sullivan, L.B.; Fiske, B.P.; et al. A PHGDH Inhibitor Reveals Coordination of Serine Synthesis and One-Carbon Unit Fate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullarky, E.; Lucki, N.C.; Zavareh, R.B.; Anglin, J.L.; Gomes, A.P.; Nicolay, B.N.; Wong, J.C.Y.; Christen, S.; Takahashi, H.; Singh, P.K.; et al. Identification of a Small Molecule Inhibitor of 3-Phosphoglycerate Dehydrogenase to Target Serine Biosynthesis in Cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 1778–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, B.; Kim, E.; Osorio-Vasquez, V.; Doll, S.; Bustraan, S.; Liang, R.J.; Luengo, A.; Davidson, S.M.; Ali, A.; Ferraro, G.B.; et al. Limited Environmental Serine and Glycine Confer Brain Metastasis Sensitivity to PHGDH Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1352–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Mainolfi, N.; Suri, V.; Jeong, S.K.; Li, S.H.J.; Friedman, A.; Manfredi, M.G.; Gitai, Z.; Kim, H.; et al. Human SHMT Inhibitors Reveal Defective Glycine Import as a Targetable Metabolic Vulnerability of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 11404–11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cañaveras, J.C.; Lancho, O.; Ducker, G.S.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Xu, X.; da Silva-Diz, V.; Minuzzo, S.; Indraccolo, S.; Kim, H.; Herranz, D.; et al. SHMT Inhibition Is Effective and Synergizes with Methotrexate in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leukemia 2021, 35, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.H.; Bantug, G.; Griss, T.; Condotta, S.; Johnson, R.M.; Samborska, B.; Mainolfi, N.; Suri, V.; Guak, H.; Balmer, M.L.; et al. Serine Is an Essential Metabolite for Effector T Cell Expansion. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wu, G. Roles of Dietary Glycine, Proline, and Hydroxyproline in Collagen Synthesis and Animal Growth. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Nilsson, R.; Sharma, S.; Madhusudhan, N.; Kitami, T.; Souza, A.L.; Kafri, R.; Kirschner, M.W.; Clish, C.B.; Mootha, V.K. Metabolite Profiling Identifies a Key Role for Glycine in Rapid Cancer Cell Proliferation. Science 2012, 336, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L.; Hsu, S.-C.; Ann, D.K.; Yen, Y.; Kung, H.-J. Arginine Signaling and Cancer Metabolism. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.G.; Byus, C.V. Effect of Dietary Arginine Restriction upon Ornithine and Polyamine Metabolism during Two-Stage Epidermal Carcinogenesis in the Mouse. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 2932–2939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yeatman, T.J.; Risley, G.L.; Brunson, M.E. Depletion of Dietary Arginine Inhibits Growth of Metastatic Tumor. Arch. Surg. 1991, 126, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-T.T.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y.-C.C.; Chi, K.K.; Chung, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Chen, Y.-R.Y.-H.Y.H.R.; Oh, M.E.; Sheng, X.; Tang, Y.; et al. Arginine Starvation Kills Tumor Cells through Aspartate Exhaustion and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrou, C.; Al-Aqbi, S.S.; Higgins, J.A.; Boyle, W.; Karmokar, A.; Andreadi, C.; Luo, J.-L.; Moore, D.A.; Viskaduraki, M.; Blades, M.; et al. Sensitivity of Colorectal Cancer to Arginine Deprivation Therapy Is Shaped by Differential Expression of Urea Cycle Enzymes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, S.C.; Chen, C.L.; Cheng, M.L.; Chu, C.Y.; Changou, C.A.; Yu, Y.L.; Yeh, S. Der; Kuo, T.C.; Kuo, C.C.; Chuu, C.P.; et al. Arginine Starvation Elicits Chromatin Leakage and CGAS-STING Activation via Epigenetic Silencing of Metabolic and DNA-Repair Genes. Theranostics 2021, 11, 7527–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missiaen, R.; Anderson, N.M.; Kim, L.C.; Nance, B.; Burrows, M.; Skuli, N.; Carens, M.; Riscal, R.; Steensels, A.; Li, F.; et al. GCN2 Inhibition Sensitizes Arginine-Deprived Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Senolytic Treatment. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 1151–1167.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Jin, F. L-Arginine Supplementation Inhibits the Growth of Breast Cancer by Enhancing Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses Mediated by Suppression of MDSCs in Vivo. BMC Cancer 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Du, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Jin, F. L-Arginine and Docetaxel Synergistically Enhance Anti-Tumor Immunity by Modifying the Immune Status of Tumor-Bearing Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 35, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, R.; Rieckmann, J.C.; Wolf, T.; Basso, C.; Feng, Y.; Fuhrer, T.; Kogadeeva, M.; Picotti, P.; Meissner, F.; Mann, M.; et al. L-Arginine Modulates T Cell Metabolism and Enhances Survival and Anti-Tumor Activity. Cell 2016, 167, 829–842.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, Y.; Kotani, H.; Iida, Y.; Taniura, T.; Notsu, Y.; Harada, M. Supplementation of L-Arginine Boosts the Therapeutic Efficacy of Anticancer Chemoimmunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2248–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lin, H.; Yuan, L.; Li, B. Combination Therapy with L-Arginine and α-PD-L1 Antibody Boosts Immune Response against Osteosarcoma in Immunocompetent Mice. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2017, 18, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, L.; Chapman, T.E.; Sanchez, M.; Yu, Y.M.; Burke, J.F.; Ajami, A.M.; Vogt, J.; Young, V.R. Plasma Arginine and Citrulline Kinetics in Adults given Adequate and Arginine-Free Diets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993, 90, 7749–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharakan, J.F.; Yu, Y.M.; Zurakowski, D.; Roth, R.M.; Young, V.R.; Castillo, L. Adaptation to a Long Term (4 Weeks) Arginine- and Precursor (Glutamate, Proline and Aspartate)-Free Diet. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovich, S.; Adler, L.; Yizhak, K.; Sarver, A.; Silberman, A.; Agron, S.; Stettner, N.; Sun, Q.; Brandis, A.; Helbling, D.; et al. Diversion of Aspartate in ASS1-Deficient Tumours Fosters de Novo Pyrimidine Synthesis. Nature 2015, 527, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberman, A.; Goldman, O.; Assayag, O.B.; Jacob, A.; Rabinovich, S.; Adler, L.; Lee, J.S.; Keshet, R.; Sarver, A.; Frug, J.; et al. Acid-Induced Downregulation of ASS1 Contributes to the Maintenance of Intracellular PH in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Woo, J.H.; Mauldin, J.P.; Jo, C.; Stone, E.M.; Georgiou, G.; Frankel, A.E. Cytotoxicity of Human Recombinant Arginase I (Co)-PEG5000 in the Presence of Supplemental L-Citrulline Is Dependent on Decreased Argininosuccinate Synthetase Expression in Human Cells. Anticancer. Drugs 2012, 23, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowles, T.L.; Kim, R.; Galante, J.; Parsons, C.M.; Virudachalam, S.; Kung, H.J.; Bold, R.J. Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines Deficient in Argininosuccinate Synthetase Are Sensitive to Arginine Deprivation by Arginine Deiminase. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, N.; Garcia-Revilla, J.; Soto, M.S.; Perryman, R.; Symington, J.; Quarles, C.C.; Healey, D.R.; Guo, Y.; Orta-Vázquez, M.L.; Mateos-Cordero, S.; et al. Arginine Deprivation Alters Microglial Polarity and Synergizes with Radiation to Eradicate Non-Arginine-Auxotrophic Glioblastoma Tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Trials Using PEG-BCT-100 in Cancer | List Results - ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Cancer&term=PEG-BCT-100&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Yau, T.; Cheng, P.N.; Chan, P.; Chan, W.; Chen, L.; Yuen, J.; Pang, R.; Fan, S.T.; Poon, R.T. A Phase 1 Dose-Escalating Study of Pegylated Recombinant Human Arginase 1 (Peg-RhArg1) in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Invest. New Drugs 2013, 31, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Cheng, P.N.; Chan, P.; Chen, L.; Yuen, J.; Pang, R.; Fan, S.T.; Wheatley, D.N.; Poon, R.T. Preliminary Efficacy, Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Quality of Life Study of Pegylated Recombinant Human Arginase 1 in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Invest. New Drugs 2015, 33, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.L.; Cheng, P.N.M.; Liu, A.M.; Chan, L.L.; Li, L.; Chu, C.M.; Chong, C.C.N.; Lau, Y.M.; Yeo, W.; Ng, K.K.C.; et al. A Phase II Clinical Study on the Efficacy and Predictive Biomarker of Pegylated Recombinant Arginase on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Invest. New Drugs 2021, 39, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Cheng, P.N.M.; Chiu, J.; Kwok, G.G.W.; Leung, R.; Liu, A.M.; Cheung, T.T.; Ng, C.T. A Phase 1 Study of Pegylated Recombinant Arginase (PEG-BCT-100) in Combination with Systemic Chemotherapy (Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin)[PACOX] in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Invest. New Drugs 2022, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.N.M.; Liu, A.M.; Bessudo, A.; Mussai, F. Safety, PK/PD and Preliminary Anti-Tumor Activities of Pegylated Recombinant Human Arginase 1 (BCT-100) in Patients with Advanced Arginine Auxotrophic Tumors. Invest. New Drugs 2021, 39, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santo, C.; Cheng, P.; Beggs, A.; Egan, S.; Bessudo, A.; Mussai, F. Metabolic Therapy with PEG-Arginase Induces a Sustained Complete Remission in Immunotherapy-Resistant Melanoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Trials Using ADI-PEG20 in Cancer | List Results - ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Cancer&term=ADI-PEG20&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Delman, K.A.; Brown, T.D.; Thomas, M.; Ensor, C.M.; Holtsberg, F.W.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Clark, M.A.; Curley, S.A. Phase I/II Trial of Pegylated Arginine Deiminase (ADI-PEG20) in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4139–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feun, L.G.; You, M.; Wu, C.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Kuo, M.T.; Marini, A.; Jungbluth, A.; Savaraj, N. Final Results of Phase II Trial of Pegylated Arginine Deiminase (ADI-PEG20) in Metastatic Melanoma (MM). J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 8528–8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, E.S.; Piccirillo, M.; Albino, V.; Di Giacomo, R.; Palaia, R.; Mastro, A.A.; Beneduce, G.; Castello, G.; De Rosa, V.; Petrillo, A.; et al. Phase II Study of Pegylated Arginine Deiminase for Nonresectable and Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2220–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feun, L.G.; Marini, A.; Walker, G.; Elgart, G.; Moffat, F.; Rodgers, S.E.; Wu, C.J.; You, M.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Kuo, M.T.; et al. Negative Argininosuccinate Synthetase Expression in Melanoma Tumours May Predict Clinical Benefit from Arginine-Depleting Therapy with Pegylated Arginine Deiminase. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, P.A.; Carvajal, R.D.; Pandit-Taskar, N.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Hoffman, E.W.; Wu, B.-W.W.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Venhaus, R.; Pan, L.; Old, L.J.; et al. Phase I/II Study of Pegylated Arginine Deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Invest. New Drugs 2013, 31, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlosarek, P.W.; Steele, J.P.; Nolan, L.; Gilligan, D.; Taylor, P.; Spicer, J.; Lind, M.; Mitra, S.; Shamash, J.; Phillips, M.M.; et al. Arginine Deprivation With Pegylated Arginine Deiminase in Patients With Argininosuccinate Synthetase 1-Deficient Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.J.; Jiang, S.S.; Hung, W.C.; Borthakur, G.; Lin, S.F.; Pemmaraju, N.; Jabbour, E.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Chen, Y.P.; Hsiao, H.H.; et al. A Phase II Study of Arginine Deiminase (ADI-PEG20) in Relapsed/Refractory or Poor-Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Qin, S.; Ryoo, B.Y.; Lu, S.N.; Yen, C.J.; Feng, Y.H.; Lim, H.Y.; Izzo, F.; Colombo, M.; Sarker, D.; et al. Phase III Randomized Study of Second Line ADI-PEG 20 plus Best Supportive Care versus Placebo plus Best Supportive Care in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, P.E.; Ready, N.; Johnston, A.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Venhaus, R.R.; Sheaff, M.; Krug, L.; Szlosarek, P.W. Phase II Study of Arginine Deprivation Therapy With Pegargiminase in Patients With Relapsed Sensitive or Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2020, 21, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.J.; Hsiao, H.H.; Hsu, Y.T.; Liu, Y.C.; Kao, H.W.; Liu, T.C.; Cho, S.F.; Feng, X.; Johnston, A.; Bomalaski, J.S.; et al. Phase I Study of ADI-PEG20 plus Low-Dose Cytarabine for the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 2946–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, M.A.; Yu, K.H.; Kelsen, D.P.; Harding, J.J.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Glassman, D.C.; Covington, C.M.; Brenner, R.; Hollywood, E.; Barba, A.; et al. A Phase 1/1B Trial of ADI-PEG 20 plus Nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2017, 123, 4556–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.J.; Do, R.K.; Dika, I. El; Hollywood, E.; Uhlitskykh, K.; Valentino, E.; Wan, P.; Hamilton, C.; Feng, X.; Johnston, A.; et al. A Phase 1 Study of ADI-PEG 20 and Modified FOLFOX6 in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Other Gastrointestinal Malignancies. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.E.; Lewis, R.; Syed, N.; Shaffer, R.; Evanson, J.; Ellis, S.; Williams, M.; Feng, X.; Johnston, A.; Thomson, J.A.; et al. A Phase I Study of Pegylated Arginine Deiminase (Pegargiminase), Cisplatin, and Pemetrexed in Argininosuccinate Synthetase 1-Deficient Recurrent High-Grade Glioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2708–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Janku, F.; Subbiah, V.; Stewart, J.; Patel, S.P.; Kaseb, A.; Westin, S.N.; Naing, A.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; Hong, D.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of ADI-PEG20 plus Cisplatin in Patients with Pretreated Metastatic Melanoma or Other Advanced Solid Malignancies. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B.K.; Thomson, J.A.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Diaz, M.; Akande, T.; Mahaffey, N.; Li, T.; Dutia, M.P.; Kelly, K.; Gong, I.Y.; et al. Phase i Trial of Arginine Deprivation Therapy with ADI-PEG 20 plus Docetaxel in Patients with Advanced Malignant Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2480–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomalaski, J.S.; Chen, K.-T.; Chuang, M.-J.; Liau, C.-T.; Peng, M.-T.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lee, C.-C.; Johnston, A.; Liu, H.-F.; Huang, Y.-L.S.; et al. Phase IB Trial of Pegylated Arginine Deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) plus Radiotherapy and Temozolomide in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2057–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, M.; Müller, I.; Kropf, P.; Closs, E.I.; Munder, M. Metabolism via Arginase or Nitric Oxide Synthase: Two Competing Arginine Pathways in Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, M.; Ramirez, M.E.; Sierra, R.A.; Raber, P.; Thevenot, P.; Al-Khami, A.A.; Sanchez-Pino, D.; Hernandez, C.; Wyczechowska, D.D.; Ochoa, A.C.; et al. L-Arginine Depletion Blunts Antitumor T-Cell Responses by Inducing Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggio, R.; Elbaum, D.; Kanyo, Z.F.; Carroll, P.J.; Cavalli, R.C.; Ash, D.E.; Christianson, D.W. Inhibition of Mn2+2-Arginase by Borate Leads to the Design of a Transition State Analogue Inhibitor, 2(S)-Amino-6-Boronohexanoic Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 8107–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steggerda, S.M.; Bennett, M.K.; Chen, J.; Emberley, E.; Huang, T.; Janes, J.R.; Li, W.; MacKinnon, A.L.; Makkouk, A.; Marguier, G.; et al. Inhibition of Arginase by CB-1158 Blocks Myeloid Cell-Mediated Immune Suppression in the Tumor Microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzybowski, M.M.; Stańczak, P.S.; Pomper, P.; Błaszczyk, R.; Borek, B.; Gzik, A.; Nowicka, J.; Jędrzejczak, K.; Brzezińska, J.; Rejczak, T.; et al. OATD-02 Validates the Benefits of Pharmacological Inhibition of Arginase 1 and 2 in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.A.; Ugel, S.; Hübbe, M.L.; Carretta, M.; Perez-Penco, M.; Weis-Banke, S.E.; Martinenaite, E.; Kopp, K.; Chapellier, M.; Adamo, A.; et al. Arginase 1–Based Immune Modulatory Vaccines Induce Anticancer Immunity and Synergize with Anti–PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2021, 9, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Trials Using INCB001158 in Cancer | List Results - ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=cancer&term=incb001158&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Clinical Trials Using Arginase Vaccine in Cancer | List Results - ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=cancer&term=arginase+vaccine&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Szefel, J.; Ślebioda, T.; Walczak, J.; Kruszewski, W.J.; Szajewski, M.; Ciesielski, M.; Stanisławowski, M.; Buczek, T.; Małgorzewicz, S.; Owczarzak, A.; et al. The Effect of L-Arginine Supplementation and Surgical Trauma on the Frequency of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and T Lymphocytes in Tumour and Blood of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Adv. Med. Sci. 2022, 67, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, J.M.; Wilmore, D.W. Is Glutamine a Conditionally Essential Amino Acid? Nutr. Rev. 1990, 48, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeters, P.B.; Grecu, I. Have We Enough Glutamine and How Does It Work? A Clinician’s View. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 60, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halama, A.; Suhre, K. Advancing Cancer Treatment by Targeting Glutamine Metabolism—A Roadmap. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzat, V.; Macedo Rogero, M.; Noel Keane, K.; Curi, R.; Newsholme, P. Glutamine: Metabolism and Immune Function, Supplementation and Clinical Translation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, N.; Brown, T.; Joanisse, S.; Aguirre, N.; West, D.; Moore, D.; Baar, K.; Breen, L.; Philp, A. Characterisation of L-Type Amino Acid Transporter 1 (LAT1) Expression in Human Skeletal Muscle by Immunofluorescent Microscopy. Nutrients 2017, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daemen, A.; Liu, B.; Song, K.; Kwong, M.; Gao, M.; Hong, R.; Nannini, M.; Peterson, D.; Liederer, B.M.; de la Cruz, C.; et al. Pan-Cancer Metabolic Signature Predicts Co-Dependency on Glutaminase and De Novo Glutathione Synthesis Linked to a High-Mesenchymal Cell State. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 383–399.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Srivastava, S.; Zhang, J. Starve Cancer Cells of Glutamine: Break the Spell or Make a Hungry Monster? Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, A.; Meguid, M.M.; Hitch, D.C. Amino Acid Profiles Correlate Diagnostically with Organ Site in Three Kinds of Malignant Tumors. Cancer 1992, 69, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, Y.; Higashiyama, M.; Gochi, A.; Akaike, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Miura, T.; Saruki, N.; Bando, E.; Kimura, H.; Imamura, F.; et al. Plasma Free Amino Acid Profiling of Five Types of Cancer Patients and Its Application for Early Detection. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, A.C.; Paolillo, V.; Radaram, B.; Qureshy, S.; Li, L.; Maity, T.; Wang, L.; Uddin, M.N.; Wood, C.G.; Karam, J.A.; et al. PET/MR Imaging of a Lung Metastasis Model of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma with (2S,4R)-4-[18F]Fluoroglutamine. Mol. imaging Biol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, M.P.S.; Harding, J.J.; Venneti, S.; Zhang, H.; Burnazi, E.M.; Bromberg, J.; Omuro, A.M.; Hsieh, J.J.; Mellinghoff, I.K.; Staton, K.; et al. In Vivo PET Assay of Tumor Glutamine Flux and Metabolism: In-Human Trial of 18f-(2S,4R)-4-Fluoroglutamine. Radiology 2018, 287, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, H.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Li, N.; Kung, H.F.; Yang, Z. Imaging Brain Metastasis Patients with 18F-(2S,4 R)-4-Fluoroglutamine. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2018, 43, e392–e399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grkovski, M.; Goel, R.; Krebs, S.; Staton, K.D.; Harding, J.J.; Mellinghoff, I.K.; Humm, J.L.; Dunphy, M.P.S. Pharmacokinetic Assessment of 18F-(2S,4R)-4-Fluoroglutamine in Patients with Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geldermalsen, M.; Wang, Q.; Nagarajah, R.; Marshall, A.D.; Thoeng, A.; Gao, D.; Ritchie, W.; Feng, Y.; Bailey, C.G.; Deng, N.; et al. ASCT2/SLC1A5 Controls Glutamine Uptake and Tumour Growth in Triple-Negative Basal-like Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2016, 35, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, Y.D.; Ganapathy, V. Glutamine Transporters in Mammalian Cells and Their Functions in Physiology and Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 2531–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]