Submitted:

01 June 2023

Posted:

02 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

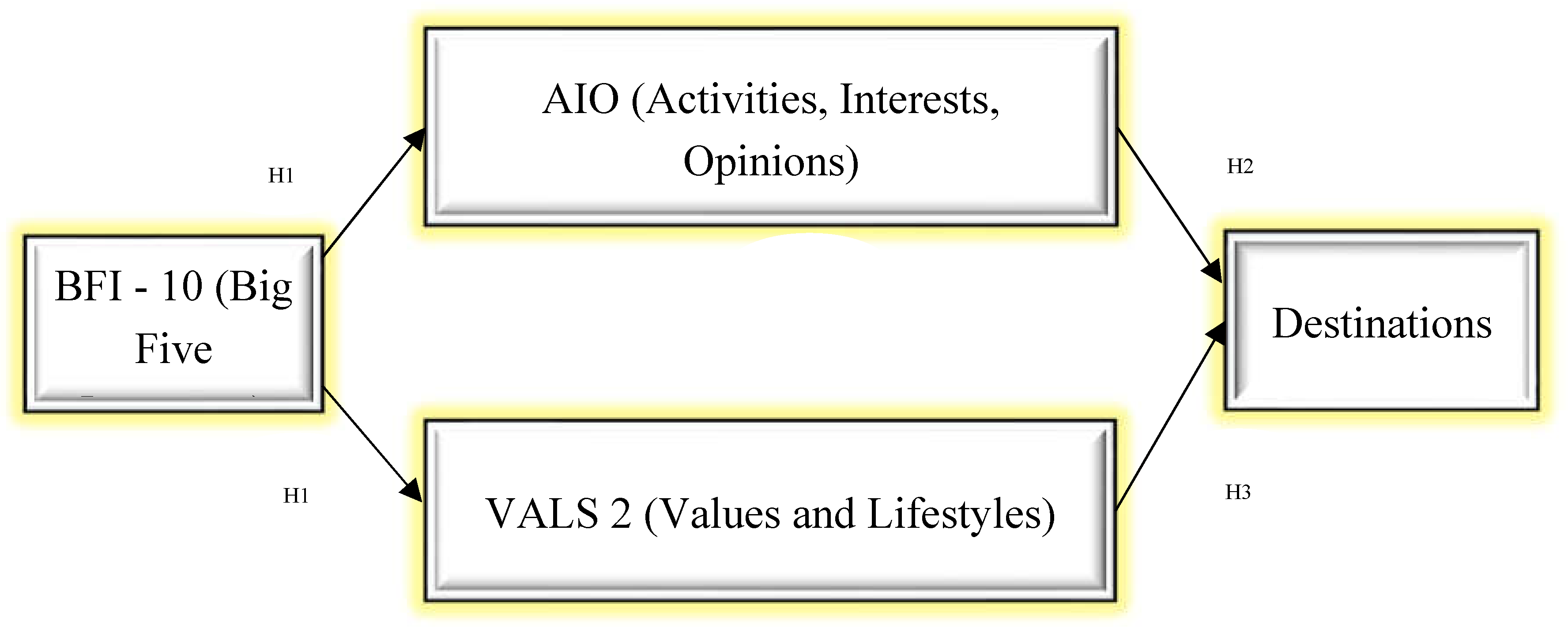

2. Theoretical background and conceptual framework

2.1. Perception of risks as (co)creators of tourist movements

2.2. Risk perception factors determined through various psychographic techniques

2.3. Aim of the present study and conceptual framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data analisys

4. Results and Discussion

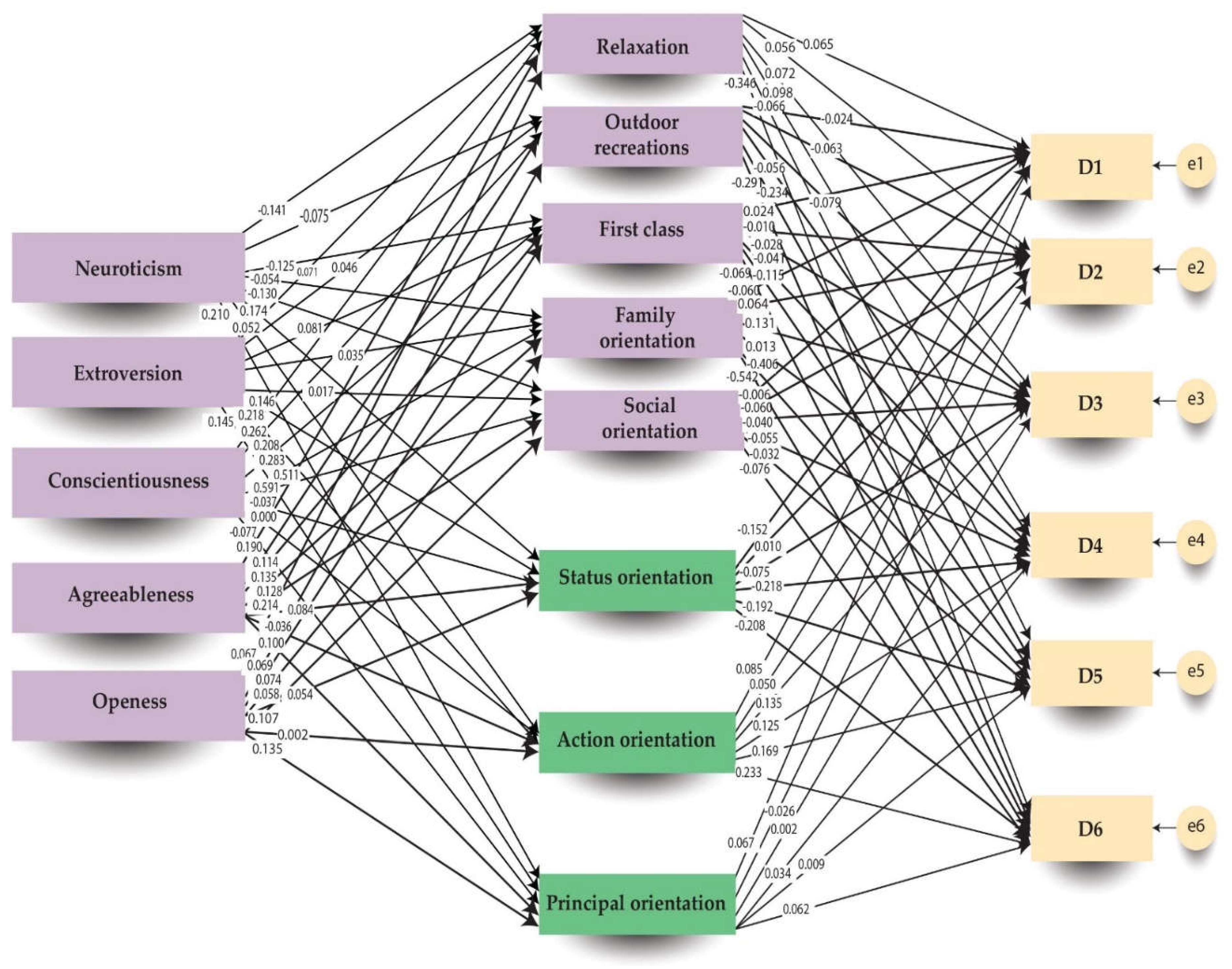

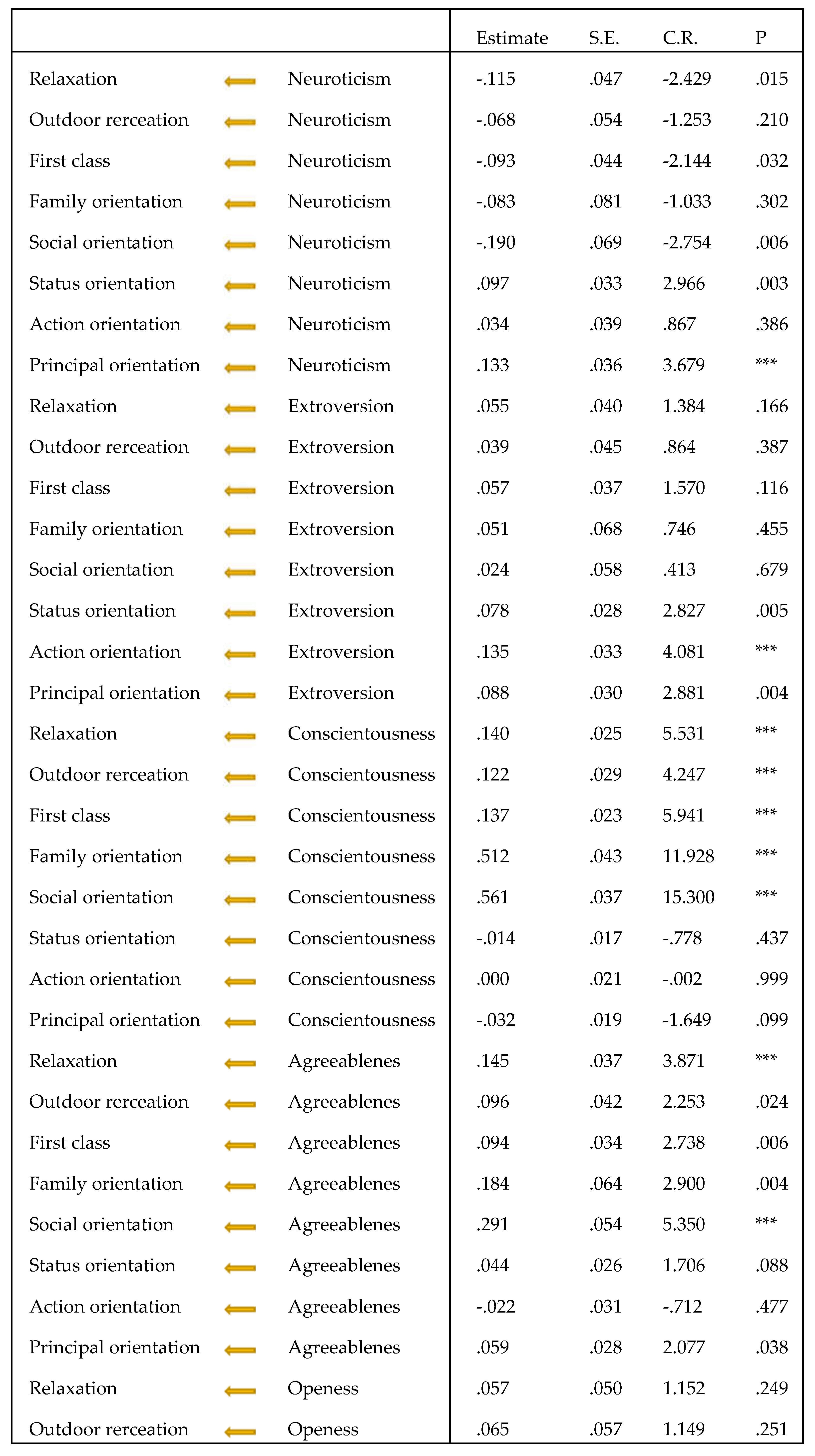

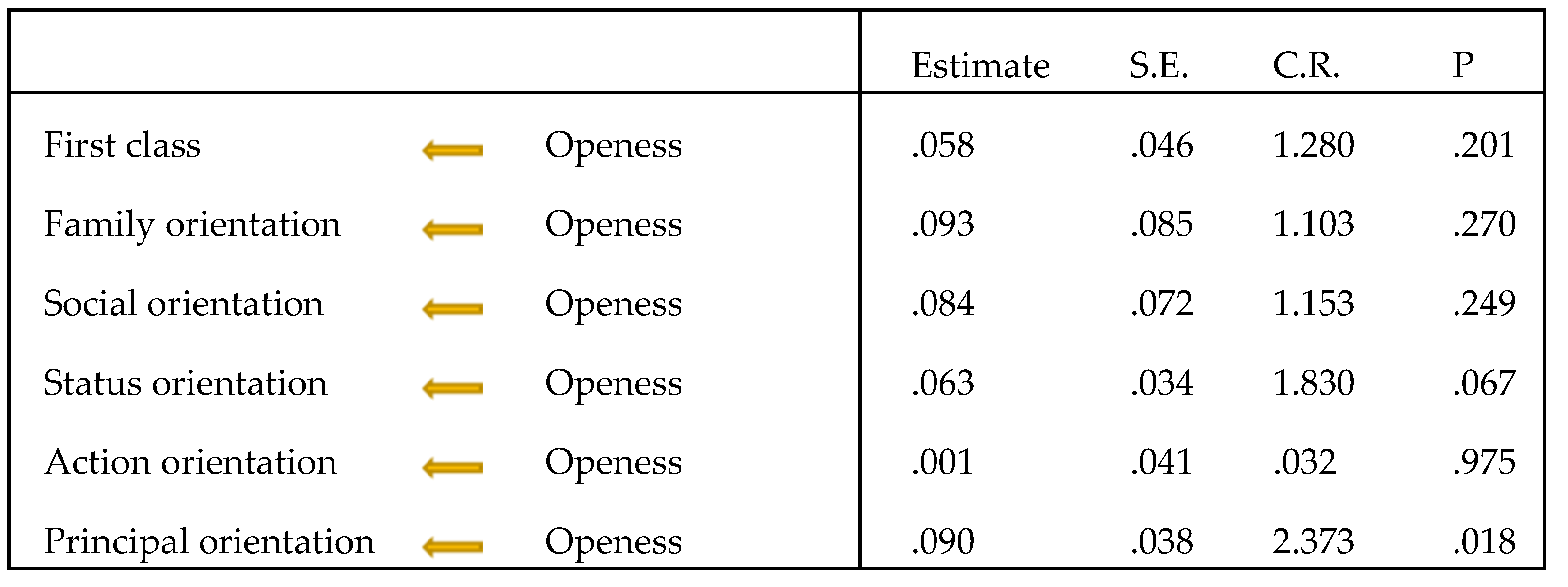

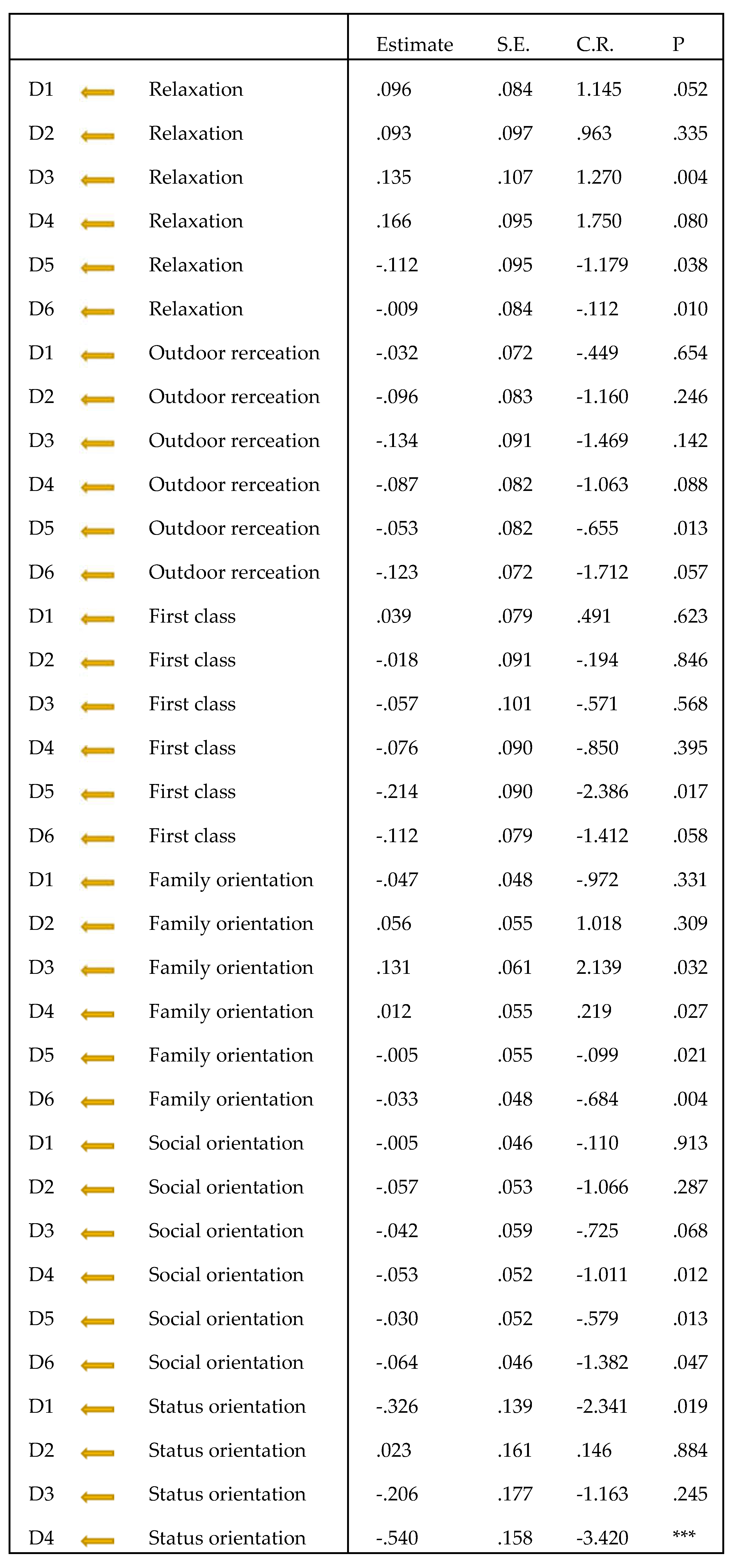

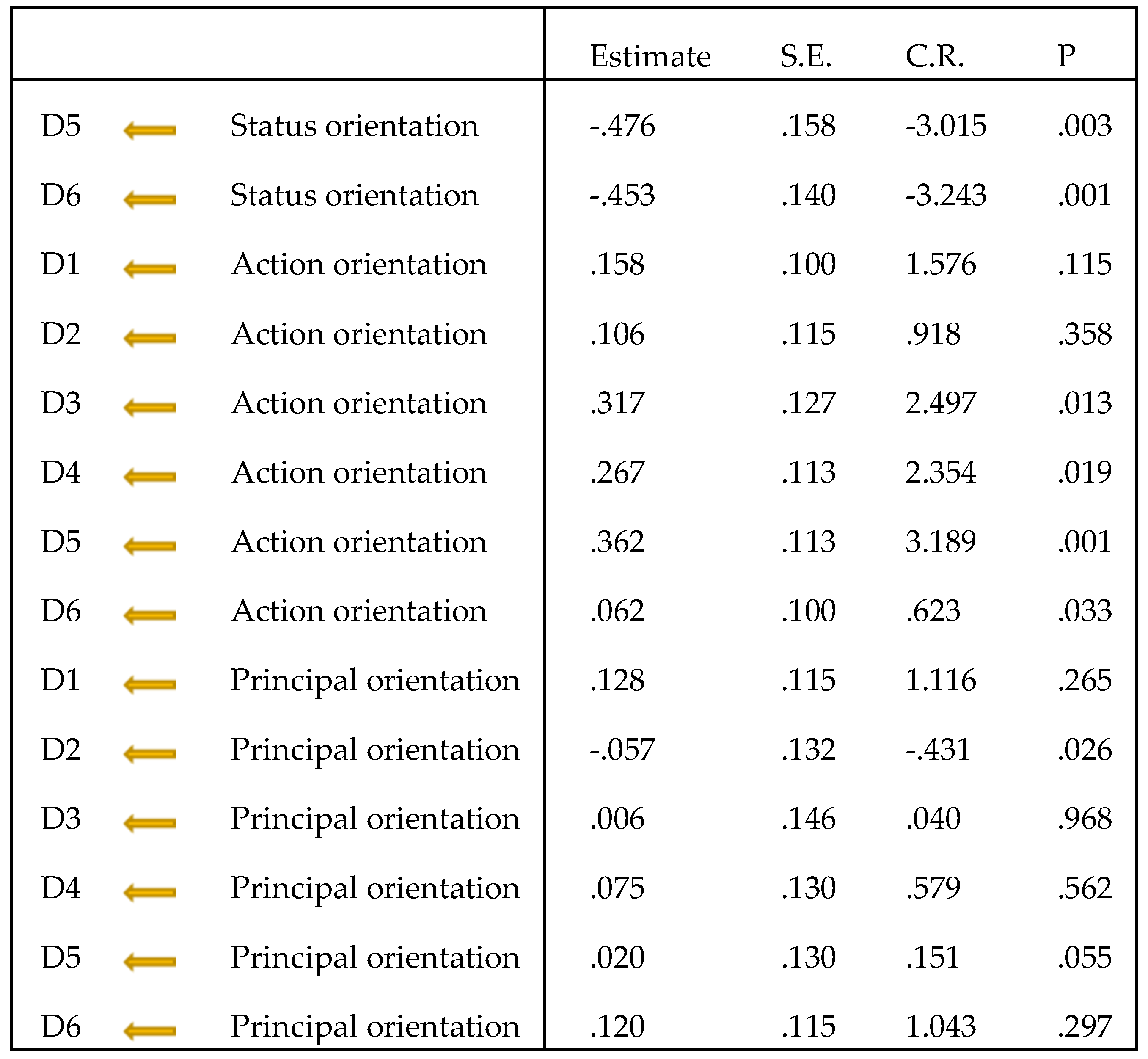

4.1. Relationships between personality traits and psychographic orientations

4.2. The relation of psychographic orientations to the selection of tourist destinations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Practical implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prüss-Ustün, A. Environmental risks and non-communicable diseases. BMJ, 2019, 365, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environment. European Comission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/risks/index_en.htm (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Beck, U. Risk society: towards a new modernity; Sage: London, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen, J.; Minor, M. Consumer behavior: A framework; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Tarlow, P. Tourism in crisis: Managing the effects of terrorism. Journal of Travel Research, 1999, 38, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, W.J. Risk concept, integral risk management and risk governance. In Risk 21-coping with risk due to natural hazards in the 21st century; Ammann, W., Dannenmann, S., Vulliet, L, Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, 2006; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, L.; O'Cass, A.; Paladino, A.; Carlson. Consumer behaviour; Pearson Higher Education AU, 2013; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Vuković, D.B.; Zobov, A.M.; Degtereva, E.A. The Nexus Between Tourism and Regional Real Growth: Dynamic Panel Threshold Testing. Journal of Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA, 2022, 71, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Tourist destination risk perception: the case of Israel. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, 2006, 14, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, C.I. Playing with risk? Participant perceptions of risk and management implications in adventure tourism. Tourism Management, 2006, 27, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. Stealth risks and catastrophic risks: On risk perception and crisis recovery strategies. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2008, 23, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism, 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Petrović, D.M.; Blešić, I.; Radovanović, M.; Syromjatnikowa, J. The Power of Fears in the Travel Decisions: COVID-19 vs. Lack of Money. Journal of Tourism Futures 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Prashant, B.; Nicholas, D.F. Problem solving in social interactions on the internet: rumor as social cognition. Social Psychology Quarterly, 2004, 67, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Tourist destination risk perception: The case of Israel. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 2006, 14, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Crotts, J.C.; Law, R. The impact of the perception of risk on international travelers. International Journal of Tourism Research 2007, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, Y. An overview of tourism risk perception. Natural Hazards, 2016, 82, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifpour, M.; Walters, G.; Ritchie, N.B. Risk perception, prior knowledge, and willingness to travel. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 2014, 20, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.W.; Morgan, M.G.; Fischhoff, B. What risks are people concerned about. Risk Analysis, 1991, 11, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 2002, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Q.; Zhang, H. Investigation of sports tourism visitors risk perception and coping behavior. Journal of Hebei Institute of Physical Education, 2012, 26, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Kumar, J. The Impact of Risk Perception and Factors on Tourists’ Decision Making for Choosing the Destination Uttarakhand/India. Journal of Tourism and Management Research, 2017, 12, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz, C.; Spaeter, S.; Auzet, A.V.; Glatron, S. Local stakeholders’ perception of muddy flood risk and implications for management approaches: A case study in Alsace (France). Land Use Policy, 2009, 26, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.; Lennon, J. JFK and dark tourism: Heart of darkness. Journal of International Heritage Studies, 1996, 2, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shondell, M. D. Disaster tourism and disaster landscape attractions after Hurricane Katrina. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2008, 2, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Mat Som, A.P.; Henderson, J.C. When disaster strikes: The Thai floods of 2011 and tourism industry response and resilience. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 2014, 20, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselló, J.; Becken, S.; Santana-Gallego, M. The effects of natural disasters on international tourism: A global analysis. Tourism Management 2020, 79, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Environmental Hazards: Assessing Risk and Reducing Disaster; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–504. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchi, M.; Montini, A. Earthquake effects on tourism in central Italy. Annals of Tourism Research, 2001, 28, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Min, J.C. Earthquake Devastation and Recovery in Tourism: The Taiwan Case. Tourism Management, 2002, 23, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Tarlow, P. Tourism in crisis: Managing the effects of terrorism. Journal of Travel Research 1999, 38, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qu, M.; Bao, J. Impact of crisis events on Chinese outbound tourist flow: A framework for post-events growth. Tourism Management, 2019, 74, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumayer, E.; Barthel, F. Normalizing economic loss from natural disasters: A global analysis. Global Environmental Change, 2011, 21, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Tourism and disaster: The tsunami waves in southern Thailand in Tourism in science research; Academy of Physical Education in Kraków, University of Information Technology and management in Rzeszów: Kraków-Rzeszów, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Becken, S.; Zammit, C.; Hendrikx, J. Developing Climate Change Maps for Tourism: Essential Information or Awareness Raising? Journal of Travel Research, 2015, 54, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Gibson, H.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B. The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2004, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I. Backpackers' risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies in Ghana. Tourism Management, 2015, 49, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Benckendorff, P. Bibliometric visualisation: An application in tourism crisis and disaster management research. Current Issues in Tourism, 2017, 63, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Sönmez, S. Lenient gun laws, perceived risk of gun violence, and attitude towards a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2019, 13, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña, L.; Prats, L.; Camprubí, R. Image and risk perceptions: An integrated approach. Current Issues in Tourism 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.M.; Wilson, M.A. The relative risk perception of travel hazards. Environment and Behavior, 2009, 41, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R. The perceived impact of risks on travel decisions. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2006, 8, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Tourist destination risk perception: The case of Israel. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 2006, 14, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, H. Disaster management and post-quake impact on tourism in Nepal. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 2016, 7, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankomah, P.K.; Crompton, J.L.; Baker, D. Influence of cognitive distance in vacation choice. Annals of Tourism Research, 1996, 23, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y. The role of security information in tourism crisis management: The missing link. In Tourism, security and safety. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann; Mansfeld, Y., Pizam, A., Eds.; Amsterdam, 2006; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Larsen, S. Flux and permanence of risk perceptions: Tourists' perception of the relative and absolute risk for various destinations. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 2016, 57, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice. Tourism Management, 2008, 29, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Cultural differences in travel risk perception. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2006, 20, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, E. J.; Jarvis, L. P. The psychology of leisure travel: Effective marketing and selling of travel services; CBI Publishing Company: Boston, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sarman, I.; Scagnolari, S.; Maggi, R. Acceptance of life-threatening hazards among young tourists: A stated choice experiment. Journal of Travel Research, 2016, 55, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavondo, F. Cultural Differences in Travel Risk Perception. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2005, 20, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavondo, F.; Reisinger, Y. Cultural consequences on traveler risk perception and safety. Tourism Analysis, 2006, 11, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Reisinger, Y. Differences in the perceived influence of natural disasters and travel risk on international travel. Tourism Geographies, 2010, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanghao, K.; Liu, W.; Li, M. High-dimensional super-resolution imaging reveals heterogeneity and dynamics of subcellular lipid membranes. Natural Community, 2020, 11, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W.S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Travel Research. 1992, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Lukić, D.; Radovanović, M.; Blešić, I.; Gajić, T.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Julia, A. Syromiatnikova.; Miljković, Đ.; Kovačić, S.; Kostić, M. How Can Tufa Deposits Contribute to the Geotourism Offer? The Outcomes from the First UNESCO Global Geopark in Serbia. Land 2023, 12, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Chien, P.M.; Sharifpour, M. Segmentation by travel related risks: An integrated approach. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2017, 34, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every, D.; McLennan, J.; Reynolds, A.; Trigg, J. Australian householders’ psychological preparedness for potential natural hazard threats: An exploration of contributing factors. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N. The precaution adoption process. Health Psychology, 1998, 7, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, W. Cognitive components in risk perception: natural versus manmade risks. Journal of Behavior Decision Making, 1992, 5, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Ivkov, M.; Tepavčević, J.; Popov Raljić, J.; Petrović, M.; Gajić, T.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Aleksić, M.; et al. Risky Travel? Subjective vs. Objective Perceived Risks in Travel Behaviour—Influence of Hydro-Meteorological Hazards in South-Eastern Europe on Serbian Tourists. Atmosphere, 2022, 13, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlberg, A. A.; Sjöberg, L. Risk perception and the media. Journal of Risk Research, 2000, 3, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L.; Moen, B. E.; Rundmo, T. Explaining risk perception. An evaluation of the psychometric paradigm in risk perception research. Rotunde, 2004, 84, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.A.; Mohd, N.I.I.; Toh, P.S. Sustainable Tourist Environment: Perception of international women travelers on safety and security in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia Social Behavior Science, 2015, 168, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.M. Travel safety introduction; China Tourism Press: Beijing, 2009; pp. 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, S. D.; Thielbar, G. W. Life styles: Diversity in American society. A psychographic and sociodemographic analysis of state park inn users. Journal of Travel Research, 1975, 28, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, D. W.; Darden, D. K.; Darden, W. R. A psychographic classification of vacation life styles. Journal of Leisure Research, 1977, 9, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwell, N. J. A psychographic and sociodemographic analysis of state park inn users. Journal of Travel Research, 1990, 28, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, J. Based tourism risk perception conceptual model—a case study of Shanghai residents. Tourism Science, 2008, 22, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, J. T. The concept and application of lifestyle segmentation. Journal of Marketing, 1974, 38, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, D. K. Travel-related lifestyle profiles of older women. Journal of Travel Research, 1988, 27, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I.; Petrović, MD.; Gajić, T.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Radovanović, M.; Popov-Raljić, J.; Yakovenko, N.V. How the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Can be Applied in the Research of the Influencing Factors of Food Waste in Restaurants: Learning from Serbian Urban Centers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanovć, M.M.; Ðoković, F.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Kovaˇci´c, S.; Jošanov Vrgović, I.; Tretyakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A. Stereotypes and Prejudices as (Non) Attractors for Willingness to Revisit Tourist-Spatial Hotspots in Serbia. Sustainability 2023a, 15, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Jeong, G.-H.; Reichel, A.; van Boemmel, H.; Lusson, J.M.; Steynberg, L.; Montmany, N. The relationship between risk-taking, sensation-seeking, and the tourist behavior of young adults: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Travel Research 2004, 42, 51–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakabati, Y.; Kapuściński, G. Personality, risk perception, benefit sought and terrorism effect. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2016, 18, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A. Lifestyle travellers: Backpacking as a way of life. Annals of Tourism Research, 2011, 38, 1535–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Taylor, L. Escape attempts: The theory and practice of resistance to everyday life; Routledge: London, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Đoković, F.; Pejanović, R.; Mojsilović, M.; Boljanović, J.; Plećić, K. Opportunities to revitalise rural tourism through the operation of agrarian cooperatives. Economics of Agriculture 2017, 64, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, C.I. Playing with risk? Participant perceptions of risk and management implications in adventure tourism. Tourism Management, 2006, 27, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond boredom and anxiety, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers in English: San Francisco, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brida, J. G.; Meleddu, M.; Pulina, M. Factors Influencing Length of Stay of Cultural Tourists. Tourism Economics, 2013, 19, 1273–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.M.; Tol, R.S.J. The impact of climate change on tourism in Germany, the UK and Ireland: a simulation study. Regional Environmental Change, 2007, 7, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.; Harris, G. The treatment of mentally disordered offenders. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 1997, 3, 126–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. Personality testing and police selection: Utility of the 'Big Five.' New Zealand. Journal of Psychology, 2000, 29, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C. C. The effects of personality traits and attitudes on student uptake in hospitality employment. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2008, 27, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saihani, S.B.; Alam, S.S.; Abdul, A.J.; Sarbini, S. The Effect of Big Five Personality in Creative Decision Making. In Creativity, Innovation and Management Proceedings of the 10th International Conference, Sousse, Tunisia, 25–28 November 2009; pp. 1157–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Tanasescu, V.; Jones, C.B.; Colombo, G.; Chorley, M.J.; Allen, S.M. The Personality of Venues: Places and the Five-Factors ('Big Five') Model of Personality. 2013 Fourth International Conference on Computing for Geospatial Research and Application; 2013; pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.A.; Pluess, M. Heritability estimates of the Big Five personality traits based on common genetic variants. Translational Psychiatry, 2015, 5, e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, M.Y. Personality of Travel Opinion Leaders. Paideuma Journal, 2019, 12, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, D. K. Psychographics are meaningful... not merely interesting. Journal of Travel Research, 1977, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, D. VALS As A Tool of Tourism Market Research: The Pennsylvania Experience. Journal of Travel Research, 1986, 24, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Beatty, S.E.; Homer, P. Alternative measurement approaches to consumer values: the List of Values (LOV) and Values and Life Style (VALS). Journal of Consumer Research 1986, 13, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalen, E. Research into values and consumer trends in Norway. Tourism Management, 1989, 10, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Hines, K.; MGraumann, C.; Greibrokk, J. The relationship between personal values and tourism behaviour: A segmentation approach. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 2010, 16, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, W. R.; Rao, C. P. A Linear Covariate Model of Warranty Attitudes and Behaviors. Journal of Marketing Research, 1979, 16, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R. D.; Miniard, P. W.; Engel, J. F. Consumer behavior, 9th ed.; Harcourt College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- John, O. P.; Donahue, E. M.; Kentle, R. L. The Big-Five Inventory-Version 4a and 54; Berkeley Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California: Berkeley, CA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory (BFI-K). Diagnostica, 2005, 51, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Huang, Y.C.; Cheng, J.S. Vacation Lifestyle and Travel Behaviors. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2009, 26, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maričić, B. Ponašanje potrošača; CID: Belgrade, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. A.; Olson, J. C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? Journal of Marketing Research, 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. A. Case and situation analysis. The Sociological Review, 1983, 31, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A. G.; Pitts, R. E. Effects of consumer life styles, demographics, and travel activities on foreign and domestic travel behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 1976, 14, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasova, O. The Big Five personality traits as antecedents of eco-friendly tourist Behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 2015, 83, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V. Big five personality traits and tourist’s intention to visit green hotels. Conference: International Conference on Contemporary issues in Science, Engineering & Management (ICCI-SEM-2017), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, February, 2017.

- Gajić, T.; Đoković, F.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.; Vukolić, D.; Mandarić, M.; Dašić, G.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Mićović, A. Pandemic Boosts Prospects for Recovery of Rural Tourism in Serbia. Land 2023b, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsdóttir, A.A. Impact of Eyjafjallajökull on tourism and international flights, B.S. thesis, Líf-ogumhverfisvísindadeild, Verkfræði- ognáttúruvísindasvið, HáskóliÍslands, Reykjavík. 2011. https://skemman.is/handle/1946/8507. 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Bhati, A.; Upadhayaya, A.; Sharma, A. National disaster management in the ASEAN-5: An analysis of tourism resilience. Tourism Review 2016, 71, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B. Crisis management and the management strategy: Time to &loop the loop. Disaster Prevention and Management, 1994, 3, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The risk perception paradox—implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk Analysis, 2012, 33, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Z.; Qian, L.; Haihua, L.; Nuoxun, L. The Impact of Chinese College Students' Perceived Stress on Anxiety During the COVID-19 Epidemic: The Mediating Role of Irrational Beliefs. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 731874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, P.M.; Sharifpour, M.; Ritchie, B.W.; Watson, B. Travelers health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. Journal of Travel Research, 2017, 56, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender Male 39.9% Female 60.1% |

Frequency of traveling I have traveled abroad several times 34.7% I travel abroad once a year 18.8% I travel abroad several times a year 46 .5% |

| Education High school 24% Faculty 67.7% MSc, PhD 8.3% |

Earning Low (≤300*) 0.7% Average (300-1.000*) 24.5% High (>1.000*) 74.8% |

| Age 18-30 26.2% 31-55 30% >56 43.8% |

Country of residence Bosnia 31.1% Hungary 3.6% Croatia 18.4% Italy 2.3% Slovenia 9.6% Montenegro 29% Austria 4.9% Germany 1.1% |

| Dimensions | m | sd | α |

| BIF-10 - Neuroticism | 2.27 | 1.238 | 0.956 |

| BIF-10 - Extroversion | 3.19 | 1.252 | 0.922 |

| BIF-10 - Conscientiousness | 3.49 | 1.827 | 0.811 |

| BIF-10 - Agreeableness | 3.34 | 1.275 | 0.725 |

| BIF-10 - Openness | 2.11 | 1.130 | 0.858 |

| AIO - Relaxation | 2.56 | 1.000 | 0.828 |

| AIO - Outdoor recreations | 2.13 | 1.084 | 0.737 |

| AIO - First class | 3.21 | 0.910 | 0.797 |

| AIO - Family orientation | 3.41 | 1.891 | 0.897 |

| AIO - Social orientation | 3.50 | 1.813 | 0.903 |

| VALS 2 - Status orientation | 3.01 | 0.677 | 0.852 |

| VALS 2 - Action orientation | 3.35 | 0.773 | 0.849 |

| VALS 2 - Principal orientation | 3.13 | 0.767 | 0.749 |

| Destination selection percentage values | |||

| Destination level risk 1 | 53.6% | ||

| Destination level risk 2 | 46.1% | ||

| Destination level risk 3 | 35.5% | ||

| Destination level risk 4 | 31% | ||

| Destination level risk 5 | 25.25% | ||

| Destination level risk 6 | 20.9% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).