Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental design

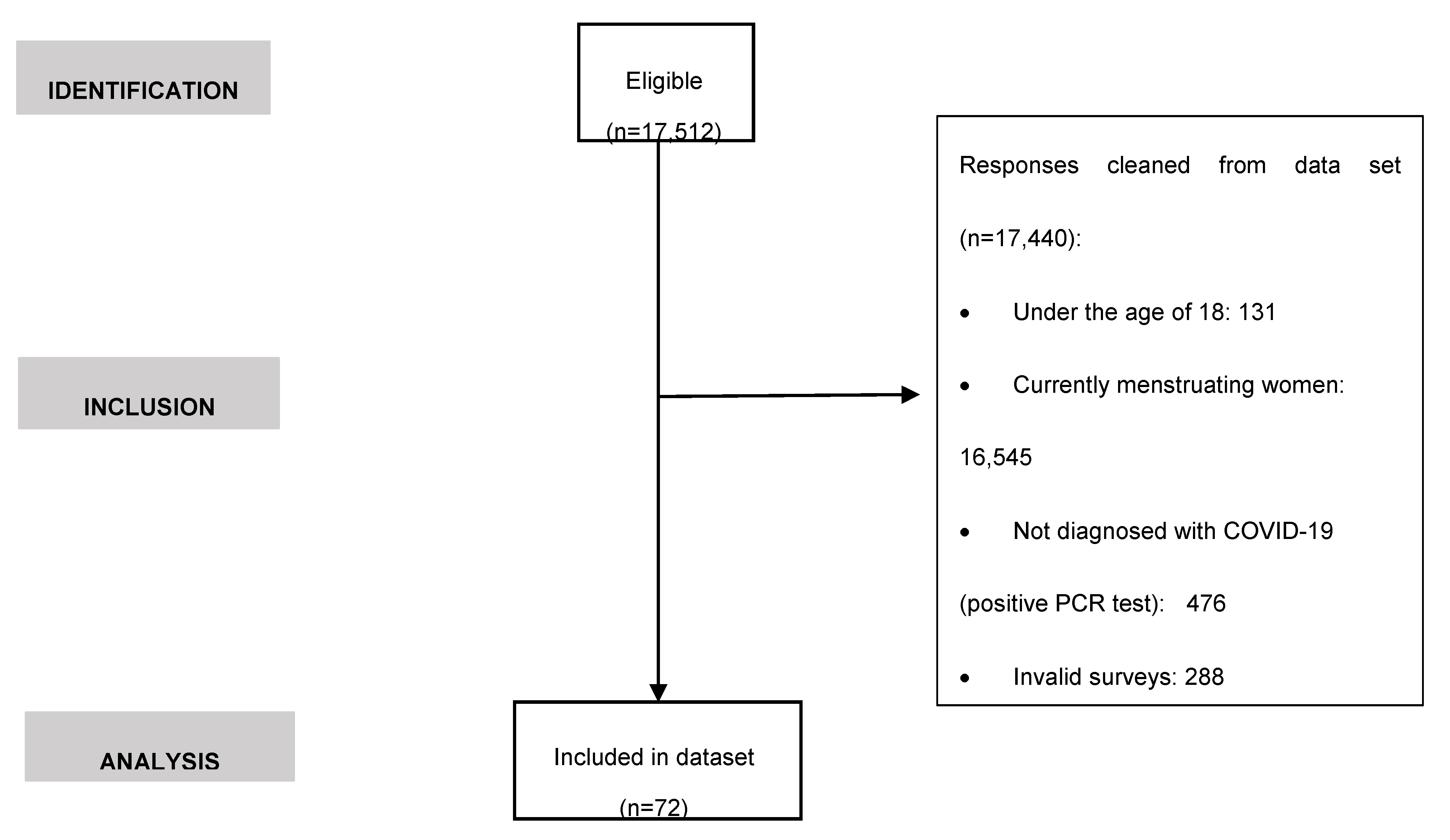

2.2. Recruitment, data collection and participants

2.3. Survey information

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anthropometric characteristics and medical history

3.2. Impact of COVID-19 disease on the menstrual health

| Variable | Category | Total (N=72) |

|---|---|---|

| Date of COVID-19 diagnosis (pandemic waves) | 1st wave | 21 (29.2) |

| 2nd wave | 17 (23.6) | |

| 3rd wave | 12 (16.7) | |

| 4th wave | 7 (9.7) | |

| 5th wave | 15 (20.8) | |

| Hospitalization | Yes | 2 (2.8) |

| No | 70 (97.2) | |

| MRD occurrence | Yes | 28 (38.9) |

| No | 44 (61.1) | |

| Types | Spotting | 8 (11.1) |

| Shorter menstrual cycle | 3 (4.2) | |

| Unexpected vaginal bleeding | 15 (20.8) | |

| Longer menstrual cycle | 1 (1.4) | |

| Length of menstrual bleeding | None | 45 (62.5) |

| Shorter | 9 (12.5) | |

| Unchanged | 16 (22.2) | |

| Longer | 8 (11.1) | |

| Flow of menstrual bleeding | Not applicable | 39 (54.2) |

| Lighter | 7 (21.2) | |

| Unchanged | 16 (48.5) | |

| Heavier | 10 (30.3) | |

| Time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and period/abnormal bleeding | I was menstruating when I got infected |

1 (1.4) |

| After 1-3 days | 3 (4.2) | |

| After 4-7 days | 6 (8.3) | |

| After 8-14 days | 5 (6.9) | |

| After more than 14 days | 15 (20.8) | |

| Coincidence with period date | Not applicable | 42 (58.3) |

| Yes | 9 (30.0) | |

| No | 16 (53.3) | |

| Not applicable | 5 (16.7) | |

| Premenstrual syndrome | ||

| Nº symptoms | 2 symptoms | 7 (28.0) |

| ≥3 symptoms | 7 (28.0) | |

| Types | None | 6 (24.0) |

| Fluid retention | 2 (8.0) | |

| Pain | 1 (4.0) | |

| Swelling | 0 (0.0) | |

| Thirst | 0 (0.0) | |

| Appetite | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 2 (2.8) | |

| Duration of MRD | 1 cycle | 4 (5.6) |

| <3 months | 3 (4.2) | |

| 3-6 months | 4 (5.6) | |

| 6-12 months | 3 (4.2) | |

| Until today | 20 (27.8) | |

| Not applicable | 38 (52.8) |

3.3. Factors associated with the occurrence or not of MRD after COVID-19 disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int.

- Guan W-J, Zheng-yi N, Yu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [CrossRef]

- Majumder J, Minko T. Recent Developments on Therapeutic and Diagnostic Approaches for COVID-19. AAPS J 2021, 23. [CrossRef]

- Kirtipal N, Kumar S, Dubey SK, et al. Understanding on the possible routes for SARS CoV-2 invasion via ACE2 in the host linked with multiple organs damage. Infect Genet Evol 2022, 99, 105254. [CrossRef]

- Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [CrossRef]

- Ni W, Yang X, Yang D, et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit Care 2020, 24, 422. [CrossRef]

- Bechmann N, Maccio U, Kotb R. , et al. COVID-19 Infections in Gonads: Consequences on Fertility? Horm Metab Res 2022, 54, 549–555. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Ma L, Xue L, et al. Co-expression of the SARS-CoV-2 entry molecules ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in human ovaries: Identification of cell types and trends with age. Genomics 2021, 113, 3449–3460. [CrossRef]

- Reis FM, Reis AM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), angiotensin-(1-7) and Mas receptor in gonadal and reproductive functions. Clin Sci 2020, 134, 2929–2941. [CrossRef]

- Carp-Veliscu A, Mehedintu C, Frincu F, et al. The Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Female Fertility: A Review of the Literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 984. [CrossRef]

- Male, V. Menstrual changes after covid-19 vaccination. BMJ 2021, 374:n2211. [CrossRef]

- Schoenbaum EE, Hartel D, Lo Y, et al. HIV infection, drug use, and onset of natural menopause. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41, 1517–24. [CrossRef]

- Giakoumelou S, Wheelhouse N, Cuschieri K, Entrican G, Howie SE, Horne AW. The role of infection in miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update 2016, 22, 116–33. [CrossRef]

- Kurmanova AM, Kurmanova GM, Lokshin VN. Reproductive dysfunctions in viral hepatitis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016, 32(sup2):37-40. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Chen G, Hou H, et al. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod Biomed Online 2021, 42, 260–267. [CrossRef]

- Ding T, Wang T, Zhang J et al. Analysis of ovarian injury associated with COVID-19 disease in reproductive-aged women in Wuhan, China: an observational study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 635255. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. , Yang, Q., Ren, X., Hu, J., Li, Z., Long, R., Xi, Q., Zhu, L., Jin, L. Investigating the impact of asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infection on female fertility and in vitro fertilization outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38: 101013. [CrossRef]

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), “Amenorrhea” (United States Government, 2021, https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/amenorrhea).

- Lord M, Sahni M. “Secondary Amenorrhea” in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK431055.

- Lee KMN, Junkins EJ, Luo C, Fatima UA, Cox ML, Clancy KBH. Investigating trends in those who experience menstrual bleeding changes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabm7201. [CrossRef]

- Spini A, Giudice V, Brancaleone V, Morgese MG, De Francia S, Filippelli A, et al. Sex-tailored pharmacology and COVID-19: Next steps towards appropriateness and health equity. Pharmacol Res 2021, 173, 105848. [CrossRef]

- Amer AA, Amer SA, Alrufaidi KM, Abd-Elatif EE, Alafandi BZ, Yousif DA, et al. Menstrual changes after COVID-19 vaccination and/or SARS-CoV-2 infection and their demographic, mood, and lifestyle determinants in Arab women of childbearing age. Front Reprod Health 2022, 4, 927211. [CrossRef]

- Khan SM, Shilen A, Heslin KM, Ishimwe P, Allen AM, Jacobs ET al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent changes in the menstrual cycle among participants in the Arizona CoVHORT study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022, 226, 270–273. [CrossRef]

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [CrossRef]

- Barabás K, Makkai B, Farkas N, Horváth HR, Nagy Z, Váradi K, et al. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination on the menstrual cycle: A retrospective study in Hungary. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13: 974788. [CrossRef]

- Schoenbaum EE, Hartel D, Lo Y, et al. HIV infection, drug use, and onset of natural menopause. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41, 1517–24. [CrossRef]

- Kallio ER, Helle H, Koskela E, Mappes T, Vapalahti O. Age-related effects of chronic hantavirus infection on female host fecundity. J Anim Ecol 2015, 84: 1264–1272. [CrossRef]

- Kurmanova AM, Kurmanova GM, Lokshin VN. Reproductive dysfunctions in viral hepatitis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016, 32(sup2):37-40. [CrossRef]

- Giakoumelou S, Wheelhouse N, Cuschieri K, Entrican G, Howie SE, Horne AW. The role of infection in miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update 2016, 22, 116–33. [CrossRef]

- Ni W, Yang X, Yang D, Bao J, Li R, Xiao Y, et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit Care 2020, 24, 422. [CrossRef]

- Ho JQ, Sepand MR, Bigdelou B, Shekarian T, Esfandyarpour R, Chauhan P, et al. The immune response to COVID-19: Does sex matter? Immunology 2022, 166, 429–443. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. Possible protective role of 17β-estradiol against COVID-19. J Allergy Infect Dis 2020, 1, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding T, Zhang J, Wang T, Cui P, Chen Z, Jiang J, et al. Potential Influence of Menstrual Status and Sex Hormones on Female Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection: A Cross-sectional Multicenter Study in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 72, e240–e248. [CrossRef]

- Costeira R, Lee KA, Murray B, Christiansen C, Castillo-Fernandez J, Ni Lochlainn M, et al. Estrogen and COVID-19 symptoms: Associations in women from the COVID Symptom Study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0257051. [CrossRef]

- Seeland U, Coluzzi F, Simmaco M, Mura C, Bourne PE, Heiland M, et al. Evidence for treatment with estradiol for women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. BMC Med 2020, 18, 369. [CrossRef]

- Suba, Z. Prevention and therapy of COVID-19 via exogenous estrogen treatment for both male and female patients. J Pharm Sci 2020, 23, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus D, Sebastião AI, Carrascal MA, Carmo AD, Matos AM, Cruz MT. Crosstalk between estrogen, dendritic cells, and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Rev Med Virol 2022, 32, e2290. [CrossRef]

- Madjunkov M, Dviri M, Librach C. A comprehensive review of the impact of COVID-19 on human reproductive biology, assisted reproduction care and pregnancy: a Canadian perspective. J Ovarian Res 2020, 13, 140. [CrossRef]

- Salamanna F, Maglio M, Landini MP, Fini M. Body Localization of ACE-2: On the Trail of the Keyhole of SARS-CoV-2. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 594495. [CrossRef]

- Sweet MG, Schmidt-Dalton TA, Weiss PM, Madsen KP. Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician 2012, 85, 35–43.

- Ray S, Ray A. Non-surgical interventions for treating heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) in women with bleeding disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 11, CD010338. [CrossRef]

- Taga A, Lauria G. COVID-19 and the peripheral nervous system. A 2-year review from the pandemic to the vaccine era. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2022, 27, 4–30. [CrossRef]

- Albert, PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015, 40, 219–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherenack EM, Salazar AS, Nogueira NF, Raccamarich P, Rodriguez VJ, Mantero AM, et al. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 is associated with menstrual irregularities among women of reproductive age. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0276131. [CrossRef]

- Scully EP, Haverfield J, Ursin RL, Tannenbaum C, Klein SL. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020, 20, 442–447. [CrossRef]

- Word Health Organization (WHO). “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022” (2021, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2022.pdf).

| Variable | Category | Total (N=27) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) a | - | 41.4±11.4 | |

| Weight (kg) a | - | 66.5±13.2 | |

| Height (cm) a | - | 163.7±6.0 | |

| BMI a, b | - | 27.8±4.6 | |

| Underweight | 5 (6.9) | ||

| Normal weight | 41 (56.9) | ||

| Pre-obesity/overweight | 13 (18.1) | ||

| Obesity I | 12 (16.7) | ||

| Obesity II | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Obesity III | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Medical history b | |||

| Autoimmune diseases | Diagnosis | Yes | 14 (19.4) |

| No | 58 (19.4) | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 1 (7.1) | |

| No | 13 (92.9) | ||

| Types | Thyroid | 6 (8.3) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (4.2) | ||

| Other | 3 (4.2) | ||

| Dermatological | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Rheumatic/articular | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Other clinical conditions | Diagnosis | Yes | 19 (27.1) |

| No | 51 (72.9) | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 5 (23.8) | |

| No | 16 (76.2) | ||

| Types | Other | 6 (8.3) | |

| Gynecological | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Cancer | 3 (4.2) | ||

| HPV | 3 (4.2) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Neurological/mental | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Respiratory | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Rheumatic/articular | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Thyroid | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Dermatological | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Allergies | Diagnosis | Yes | 26 (36.1) |

| No | 46 (63.9) | ||

| Gynecological history a, b | |||

| Age 1st menstruation |

- | 12.8±1.4 | |

| Amenorrhea | Causes | Contraceptives | 23 (31.9) |

| Postmenopause | 16 (22.2) | ||

| Other | 14 (19.4) | ||

| Perimenopause | 16 (22.2) | ||

| Breastfeeding | 8 (11.1) | ||

| Current/ past use of contraceptives | Time of use | <10 years | 23 (31.9) |

| Types | >10 years | 6 (8.3) | |

| None | 43 (59.7) | ||

| Hormonal | 23 (31.9) | ||

| IUD (nonhormonal) | 6 (8.3) | ||

| Reproduction | Have you ever been pregnant? | Yes | 44 (61.1) |

| Nº pregnancies | No | 28 (38.9) | |

| 0-2 | 60 (83.3) | ||

| >2 | 16 (16.7) | ||

| Nº children | 0-2 | 68 (94.4) | |

| >2 | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Diseases | Diagnosis | Yes | 38 (52.8) |

| No | 34 (47.2) | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 7 (18.4) | |

| No | 34 (47.2) | ||

| Types | PCOS | 13 (18.1) | |

| EndometriosisHeavy menstrual bleeding | 8 (11.1)13(18.1) | ||

| Other | 8 (11.1) | ||

| Fibroids | 4 (5.6) | ||

| Menorrhagia | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Adenomyosis | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Uterine bleeding | 0 (0.0) |

| Subgroup | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | n-MRD (n=44) |

MRD (n=28) |

X2 | p-value | |

| Age (years)a | 41.4±12.3 | 41.5±9.9 | - | 0.954 | ||

| Weight (kg)a | - | 66.1±13.8 | 67.0±12.5 | - | 0.785 | |

| Height (cm)a | - | 163.6±6.5 | 163.8±5.3 | - | 0.889 | |

| BMI a,b | - | 24.7±5.0 | 24.9±4.1 | - | 0.768 | |

| Underweight | 3 (6.8) | 2 (7.1) | 0.683 | |||

| Normal weight | 27 (61.4) | 14 (50.0) | ||||

| Pre-obesity/ overweight | 6 (13.6) | 7 (25.0) | ||||

| Obesity I | 7 (15.9) | 5 (17.9) | ||||

| Obesity II | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Obesity III | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Medical history b | ||||||

| Autoimmune diseases | Types | Dermatological | 1 (2.3) | 1 (3.6) | 0.107 | 0.744 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 (2.3) | 2 (7.1) | 1.016 | 0.313 | ||

| Rheumatics/ articular | 1 (2.3) | 1 (3.6) | 0.107 | 0.744 | ||

| Other | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1.992 | 0.158 | ||

| Thyroid | 3 (6.8) | 3 (10.7) | 0.340 | 0.560 | ||

| Other clinical conditions | Types | Cardiovascular | 1 (2.3) | 1 (3.6) | 0.107 | 0.744 |

| Cancer | 2 (4.5) | 1 (3.6) | 0.041 | 0.840 | ||

| Dermatological | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.309 | 0.253 | ||

| Gynecological | 3 (6.8) | 1 (3.6) | 0.344 | 0.558 | ||

| Neurological/ mental | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.645 | 0.422 | ||

| Other | 4 (9.1) | 2 (7.1) | 0.085 | 0.711 | ||

| Respiratory | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | 1.594 | 0.207 | ||

| Rheumatic/ articular | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | 1.594 | 0.207 | ||

| Thyroid | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.645 | 0.422 | ||

| HPV | 1 (2.3) | 2 (7.1) | 1.016 | 0.313 | ||

| Allergies | - | 31 (70.5) | 13 (29.5) | 2.114 | 0.146 | |

| Gynecological history a,b | ||||||

| Age 1st menstruation | - | 12.7±14 | 12.8±1.4 | 0.921 | ||

| Contraceptives | Time of use | <10 years | 12 (27.3) | 11 (39.3) | 1.810 | 0.405 |

| >10 years | 3 (6.8) | 3 (10.7) | ||||

| Types | None | 29 (65.9) | 14 (50.0) | 2.511 | 0.285 | |

| Hormonal | 11 (25.0) | 12 (42.9) | ||||

| IUD (nonhormonal) | 4 (9.1) | 2 (7.1) | ||||

| Reproduction | Have you ever been pregnant? | Yes | 27 (61.4) | 17 (60.7) | 0.003 | 0.956 |

| No | 17 (38.6) | 11 (39.3) | ||||

| Nº pregnancies | 0-2 | 37 (84.1) | 23 (82.1) | 0.047 | 0.29 | |

| > 2 | 7 (15.9) | 5 (17.9) | ||||

| Nº children | 0-2 | 40 (90.9) | 28 (100.0) | 2.695 | 0.101 | |

| > 2 | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Amenorrhea | Types | Perimenopause | 3 (6.8) | 8 (28.6) * | 6.809 | 0.033 |

| Postmenopause | 12 (27.3) | 4 (14.3) | ||||

| Other | 29 (65.9) | 16 (57.1) | ||||

| Diseases | Types | Adenomyosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Endometriosis | 3 (6.8) | 5 (17.9) | 2.111 | 0.146 | ||

| Fibroids | 2 (4.5) | 2 (7.1) | 0.220 | 0.639 | ||

| Menorrhagia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | 1.594 | 0.207 | ||

| Other | 5 (11.4) | 3 (10.7) | 0.007 | 0.932 | ||

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | 4 (9.1) | 9 (32.1) * | 6.146 | 0.013 | ||

| Uterine bleeding | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | ||||

| PCOS | 8 (18.2) | 5 (17.9) | 0.001 | 0.972 | ||

| COVID-19 | ||||||

| Date of COVID-19 diagnosis (pandemic waves) |

1st wave | 15 (34.1) | 6 (21.4) | 10.378 | 0.035 | |

| 2nd wave | 9 (20.5) | 8 (28.6) | ||||

| 3rd wave | 10 (22.7) | 2 (7.1) | ||||

| 4th wave | 1 (2.3) | 6 (21.4) * | ||||

| 5th wave | 9 (20.5) | 6 (21.4) | ||||

| Hospitalization | Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.1) | 3.233 | 0.072 | |

| No | 44 (100.0) | 26 (92.9) |

| Subgroup MRD (n=28) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | AOR(CI95%) | p-value |

| Amenorrhea | Perimenopause | 4.608(1.018-20.856) | 0.047 |

| Postmenopause | 0.541(0.139-2.103) | 0.375 | |

| Other | 1 | ||

| Gynecological history | |||

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | Yes | 4.857(1.239-19.031) | 0.023 |

| No | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).