Submitted:

04 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: The East Naples Peri-Urban Fringe

2.1.1 The Municipal Urban Plan of Casoria

2.1.2 The Urban Recovery Programme of the Ponticelli Neighbourhood in Naples

2.2. Data Sources and Approach

2.3. First Phase: Identification of Evaluation Indicators

2.4. Second Phase: Spatial Sustainability Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Results of the First Phase: Construction of Evaluation Indicators

3.1.1. Social Dimension

- social housing;

- sustainable mobility;

- civic use of public properties;

- illegal building rate;

- civic cornerstones.

- soil sealing;

- forest area index;

- Ecosystem fragmentation.

- 15 metres for urban roads;

- 7.5 metres for the urban neighbourhood road network;

- 5 metres for fences and other infrastructure.

- the cancellation of the buffer for fences, as both urban planning instruments provide that such works are not allowed in peri-urban areas;

- the cancellation of the buffer in areas where local roads are reclassified as agricultural service roads;

- the reduction of the buffer by 50% in areas characterised by public crossing routes;

- the reduction of the buffer by 50% in areas subject to mitigation through reforestation and thus ecological reconnection.

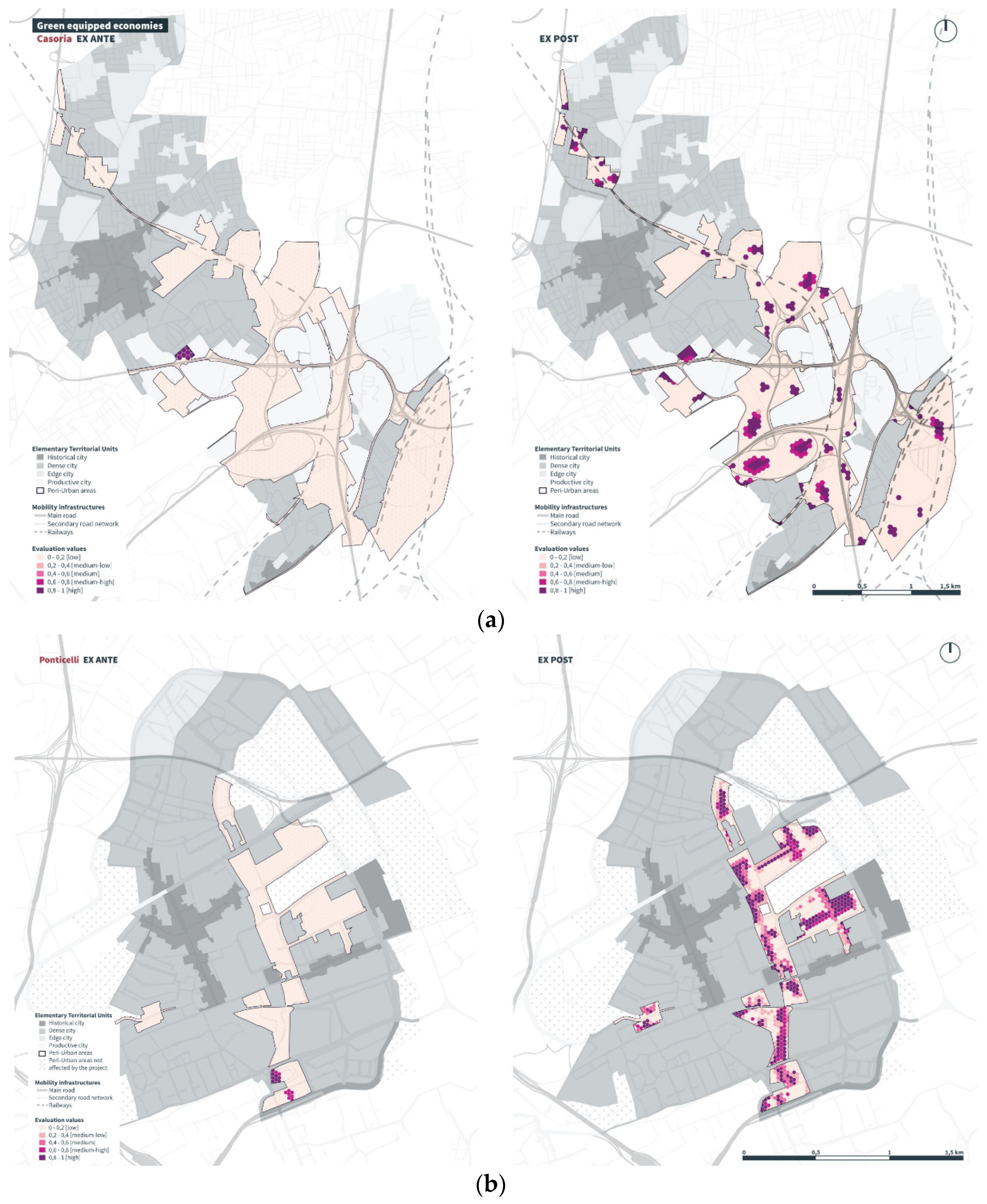

3.1.3. Economic Dimension

- agri-environmental productions;

- green equipped economies.

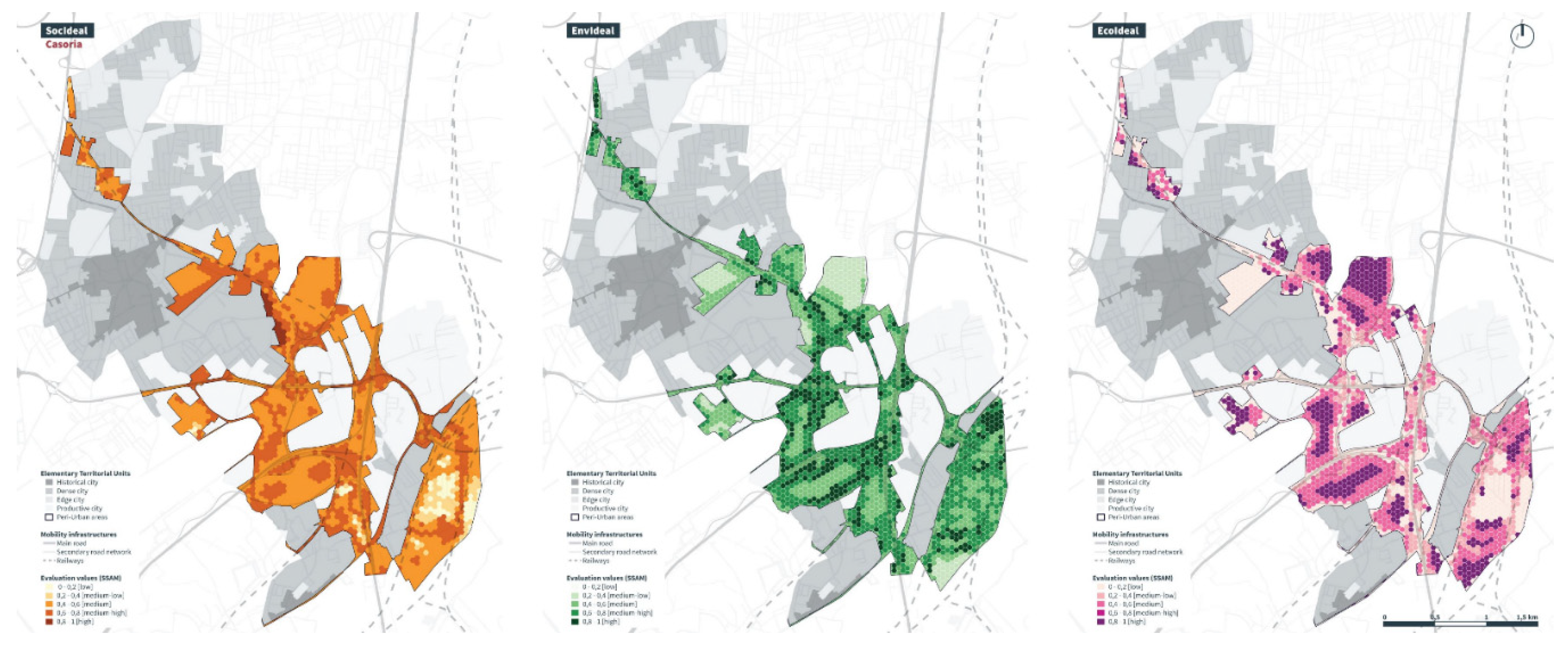

3.2. Results of the Second Phase: Dimension Assessment and Sustainability Index

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- Bond, A.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Pope, J. Sustainability assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2012, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, B. A framework for environmental sustainability assessment and assurance. In Handbook of environmental impact assessment; Petts, J., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, R.B. Sustainability assessment: criteria, processes and applications; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 13: 978-1-84407-050-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sheate, W.R. The evolving nature of environmental assessment and management: linking tools to help deliver sustainability – tools, techniques & approaches for sustainability. In Tools, techniques and approaches for sustainability: collected writings in environmental assessment policy and management; Sheate, W.R., Ed.; World Scientific: Toh Tuck Link, SGP, 2009; pp. 1–29. ISBN 13 978-981-4289-68-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hacking, T.; Guthrie, P. A framework for clarifying the meaning of triple bottom-line, integrated, and sustainability assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2008, 28, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffoni, L. La “dottrina” dello sviluppo sostenibile e della solidarietà generazionale. Il giusto procedimento di normazione ambientale. Federalismi.it: rivista di diritto pubblico italiano, comparato, europeo 2007, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Low, N.; Gleeson, B. Justice, Society and Nature. An exploration of politcal ecology, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; pp. 29–48. ISBN 0-203-00668-2.

- Mininni, M. Abitare il territorio e costruire paesaggi. In Campagne urbane, 2nd ed.; Pierre Donadie; Donzelli Editore: Roma, IT, 2013; pp. XIII–LV. ISBN 978-88-6036-966-6. [Google Scholar]

- Attademo, A.; Formato, E. Ripartire dalle cincture urbane di transizione. In Fringe Shifts; Attademo, A., Formato, E., Eds.; LISt Lab: Trento, IT, 2018; pp. 10–25. ISBN 978-88-9877-458-6. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, M. Un urbanistica senza crescita? In Urbanistica per una diversa crescita; Russo, M., Ed.; Donzelli Editore: Roma, IT, 2014; pp. XV–XXX. ISBN 978-88-6843-091-7. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Tracciare la rotta; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milano, IT, 2018; pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, T.T.R.; In Conversation with Richard T., T. Forman. LA+ Interdisciplinary Journal of Landscape Architecture 2015, 1, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, R.; Drozdz, Z.; Padgett Kjaersgaard, S. Hotspot Cities: Identifying peri-urban conflict zones. Journal of Landscape Architecture 2019, 14, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravetz, J.; Fertner, C.; Sick Nielsen, T. The Dynamics of Peri-Urbanization. In Peri-urban futures: Scenarios and models for land use change in Europe; Nilsson, K., Pauleit, S., Bell, S., Aalbers, C., Sick Nielsen, T., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2012; pp. 13–44. ISBN 978-3-642-30529-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wandl, A.; Magoni, M. Sustainable Planning of Peri-Urban Areas: Introduction to the Special Issue. Planning Practice & Research 2017, 32, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareglio, S.; Pozzi, F. Analisi e caratterizzazione dei sistemi agricoli e territoriali della Lombardia. In Analisi e governo dell’agricoltura periurbana (AGAPU). Rapporto finale di ricerca; Pareglio, S., Ed.; Milano, IT: Fondazione Lombardia per l’Ambiente: Milano, IT, 2013; pp. 24–60. ISBN 978-88-8134-116-0. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, A. Defining suburbs. Journal of Planning Literature 2012, 27, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mininni, M. Approssimazioni alla città, 1nd ed.; Donzelli Editore: Roma, IT, 2012; pp. 13–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Theses on Urbanization. Public Culture 2013, 25, 85–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N., Schmid, C. Planetary urbanisation. In Urban Constellations, 1nd ed.; Gandy, M., Ed.; Jovis: Berlin, DE, 2011; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism, 1nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2003; pp. 137–182. ISBN 0-19-926431-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mininni, M. Né città, né campagna. Un terzo territorio per una società paesaggista. Urbanistica 2005, 128, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretto, M.; Caiani, G.; Mugnano, S. Classificazione dei comuni lombardi sulla base della morfologia sociale e delle funzioni: 4 possibili scenari interpretativi del territorio. In Analisi e governo dell’agricoltura periurbana (AGAPU). Rapporto finale di riceerca; Pareglio, S., Ed.; Milano, IT: Fondazione Lombardia per l’Ambiente: Milano, IT, 2013; pp. 116–153. ISBN 978-88-8134-116-0. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, D.; McGregor, D.; Thompson, D. Contemporary Perspectives on the Peri-Urban Zones of Cities in Developing Areas. In The Peri-Urban Interface: approches to sustainable natural and human resource use, 1nd ed.; Simon, D., McGregor, D., Thompson, D., Eds.; Earthscan: Londra, UK, 2006; pp. 3–17. ISBN 13: 978-1-84407-188-3. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A. Understanding Environmental Change in the Contest of Rural-Urban Interaction. In The Peri-Urban Interface: approches to sustainable natural and human resource use, 1nd ed.; Simon, D., McGregor, D., Thompson, D., Eds.; Earthscan: Londra, UK, 2006; pp. 30–43. ISBN 13: 978-1-84407-188-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J. W; Steffen, K; Noone, Å; Persson, F. S; Chapin, III, E; Lambin, T. M; Lenton, M; Scheffer, C; Folke, H; Schellnhuber, B; Nykvist, C. A; De Wit, T; Hughes, S; van der Leeuw, H; Rodhe, S; Sörlin, P. K; Snyder, R; Costanza, U; Svedin, M; Falkenmark, L; Karlberg, R. W; Corell, V. J; Fabry, J; Hansen, B; Walker, D; Liverman, K; Richardson, P. Crutzen, and J. Foley. Planetary boundaries:exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta M, Poli G. Landscape Services Assessment: A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Spatial Decision Support System (MC-SDSS). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, C.P.; Oom, S.P.; Beecham, J.A. Rectangular and hexagonal grids used for observation, experiment and simulation in ecology. Ecological Modellling 2007, 206, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Maier, S.D.; Horn, R.; Holländer, R.; Aschemann, R. Development of an Ex-Ante Sustainability Assessment Methodology for Municipal Solid Waste Management Innovations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzarella, F.; Turcanu, C.; Abelshausen, B.; Cappuyns, V. Community capitals and (social) sustainability: Use and misuse of asset-based approaches in environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 329, 117122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, M.; De Toro, P.; Fusco Girard, L.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Iodice, S. Indicators for Ex-Post Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Impacts in the Perspective of the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Better Regulation Practices across the European Union. Chapter 4. Ex-post Review of Laws and Regulations Across the European Union; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Orozco, B.; Rosell, J.A.; Merçon, J.; Bueno, I.; Alatorre-Frenk, G.; Langle-Flores, A.; Lobato, A. Challenges and Strategies in Place-Based Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainability: Learning from Experiences in the Global South. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellefontaine, T.; Wisener, R. The Evaluation of Place-Based Approaches. Questions for Further Research; Policy Horizons Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S.R.; Folke, C.; Norström, A.; Olsson, O.; Schultz, L.; Agarwal, B.; Balvanera, P.; Campbell, B.; Castilla, J.C.; Cramer, W. Program on ecosystem change and society: An international research strategy for integrated social–ecological systems. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2012, 4, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balvanera, P.; Calderón-Contreras, R.; Castro, A.J.; Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Jacobs, S.; Martín-López, B.; Arbieu, U.; Speranza, C.I.; Locatelli, B.; Pérez Harguindeguy, N.; Ruiz Mercado, I.; Spierenburg, M. J.; Vallet, A.; Lynes, L.; Gillson, L. Interconnected place-based social–ecological research can inform global sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2017, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.; Saisana, M.; Paruolo, P.; Vandecasteele, I. Weights and importance in composite indicators: closing the gap. Ecological Indicators 2017, 80, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, O. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach. In Knowledge Solutions; Serrat, O., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, SG, 2017; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Hauschild, M.Z. Indicators for environmental sustainability. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppinger, C. R.; Gorman, M.; Markey, A.; Stanley, D. A. Are indicators useful for measuring and supporting the sustainability of forest use? A Zambian case study. Forest Policy and Economics 2023, 149, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D. Indicators and information systems for sustainable development. In The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Cities, 1st ed.; Satterthwaite, D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 1–30. ISBN 978–13–1580–046–2. [Google Scholar]

- Warhurst, A., 2002. Sustainability Indicators and Sustainability Performance Management. Report to the Project: Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development (MMSD). International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): Warwick, England. Available online: Sustainability Indicators and Sustainability Performance Management (iied.org) (accessed 15 December 2022).

- Singh, K. R.; Murty, H. R.; Gupta, S. K.; Dikshit, A. K. An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecological Indicators 2012, 15, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, M.; Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S. Tools for Composite Indicators Building. European Commission, 2005. Available online: (PDF) Tools for Composite Indicators Building (researchgate.net) (accessed 18 November 2022).

- Rocchi, L.; Ricciolini, E.; Massei, G.; Paolotti, L.; Boggia, A. Towards the 2030 Agenda: Measuring the Progress of the European Union Countries through the SDGs Achievement Index. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggia, A.; Massei, G.; Pace, E.; Rocchia, L.; Paolotti, L.; Attard, M. Spatial multicriteria analysis for sustainability assessment: A new model for decision making. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, P.; De Toro, P.; Franciosa, A. Evaluation of urban processes on health in Historic Urban Landscape approach: Experimentation in the Metropolitan Area of Naples (Italy). Quality Innovation Prospery 2016, 21, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Cerreta, M.; De Toro, P. Towards a local comprehensive productive development strategy: A methodological proposal for the Metropolitan City of Naples. Quality Innovation Prospery 2016, 21, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J.; Rinner, C. Multicriteria Decision Analysis in Geographic Information Science; Springer: Berlin, DE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg, C.A.; Nijkamp, P. Multifunctional land use in the city: A typological overview. Built Environment 2004, 30, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, D.; Thomas, I. Location of Public Services: From Theory to Application. In Models in Spatial Analysis; Sanders, L., Ed.; ISTE Ltd: London, UK, 2007; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, K. K. Geographic Information Science and Spatial Analysis for the Humanitie. In The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the future humanities scholarship; Bodenhamer, D. J., Corrigan, J., Harris, T. M., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, USA, 2010; pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.L. Comparison of weights in TOPSIS models. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2004, 40, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.B.; Keisler, J.; Linkov, I. Multi-criteria decision analysis in environmental sciences: Ten years of applications and trends. Science of The Total Environment 2011, 409, 3578–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Herath, A. A critical review of multi-criteria decision making methods with special reference to forest management and planning. Ecological Economics 2009, 68, 2535–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, A.; De Toro, P.; Fierro, N.; Montone, E. Integration between GIS and Multi-Criteria Analysis for Ecosystem Services Assessment: A Methodological Proposal for the National Park of Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA. XIII Rapporto “Qualità dell’ambiente urbano”, 2017. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/stato-dellambiente/xiii-rapporto-qualita-dell2019ambiente-urbano-edizione-2017 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Magnaghi, A. Il principio territoriale, 1st ed.; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, IT, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cellamare, C. Città fai-da-te; Donzelli Editore: Roma, IT, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- INFC—Inventario Nazionale delle Foreste e dei Serbatoi Forestali di Carbonio (2005–2015). Available online: https://www.sian.it/inventarioforestale/jsp/dati_carquant_tab.jsp?menu=3 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Schirpke, U.; Scolozzi, R.; De Marco, C.; Modello Dimostrativo di Valutazione Qualitativa e Quantitativa dei Servizi Ecosistemici Nei Siti Pilota; Parte1: Metodi di Valutazione. Report del Progetto Making Good Natura (LIFE+11 ENV/IT/000168); EURAC Research: Bolzano, Italy; Available online: http://www.lifemgn-serviziecosistemici.eu/IT/Documents/doc_mgn/LIFE+MGN_Report_B1.1.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Jaeger, J. A. G. Landscape division, splitting index, and effective mesh size: New measures of landscape fragmentation. Landscape ecology 2000, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chailloux, M.; Amsallem, J.; Chéry J., P. FragScape v1.0. INRAE - Ministère de la Transition Ecologique et Solidaire, 2019. Available online: https://www.umr-tetis.fr/jdownloads/equipements/FragScape_UserGuide_fr.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Brenner, N. The Hinterland, Urbanized? AD/Architectural Design 2016, 86, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J. S. Rational Ecology: Environment and Political Economy; Blackwell: New York, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- M. Potschin, R. Haines-Young. Landscapes, sustainability and the place-based analysis of ecosystem services. Landscape Ecology 2013, 28, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension of Sustainability | SDGs | Target SDGs | Indicators |

| Social | 11 Sustainable cities and communities |

11.1 By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums | Social housing |

| 11.2 By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons | Sustainable mobility |

||

| 11.3 By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries | Civic use of public properties |

||

| 11.4 Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world's cultural and natural heritage | Illegal building rate | ||

| 11 Sustainable cities and communities 17 Partnerships for the goals |

11.7 By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities 17.17 Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships |

Civic cornerstones | |

| Environmental | 15 Life on land data |

15.1 By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services, in particular forests, wetlands, mountains and drylands, in line with obligations under international agreements | Forest area index |

| 15.3 By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world | Soil sealing |

||

| Ecosystem Fragmentation | |||

| Economic | 2 Zero Hunger | By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality |

Agri-environmental productions |

| 8 Decent work and economic growth | 8.3 Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small-and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services | ||

| 12 Responsible consumption and production |

12.2 By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources |

||

| 8 Decent work and economic growth |

8.4 Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production, with developed countries taking the lead | Green equipped economies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).