Submitted:

05 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Consideration

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Student Characteristics

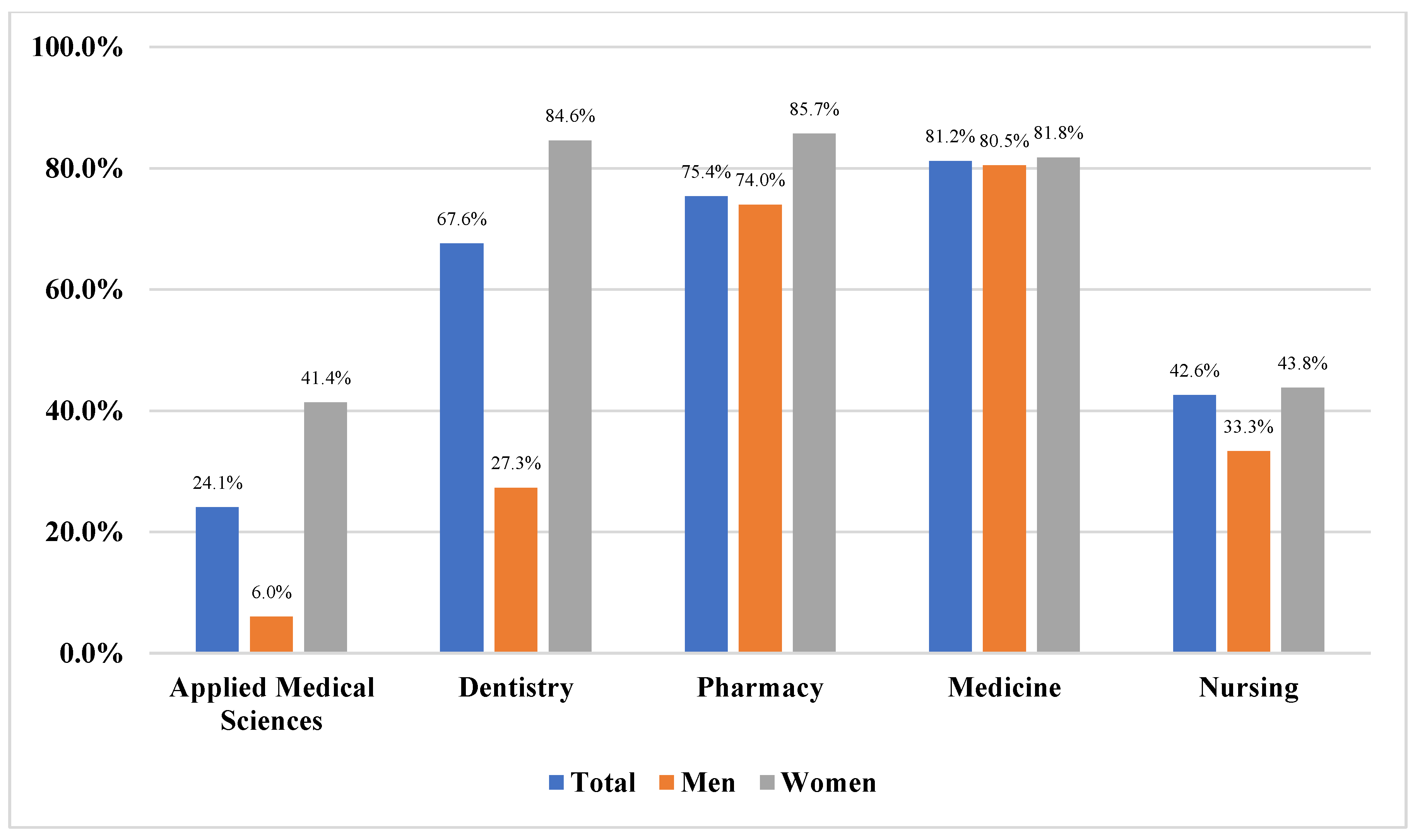

3.2. Awareness about the HPV Vaccine

3.3. Knowledge about HPV Vaccine

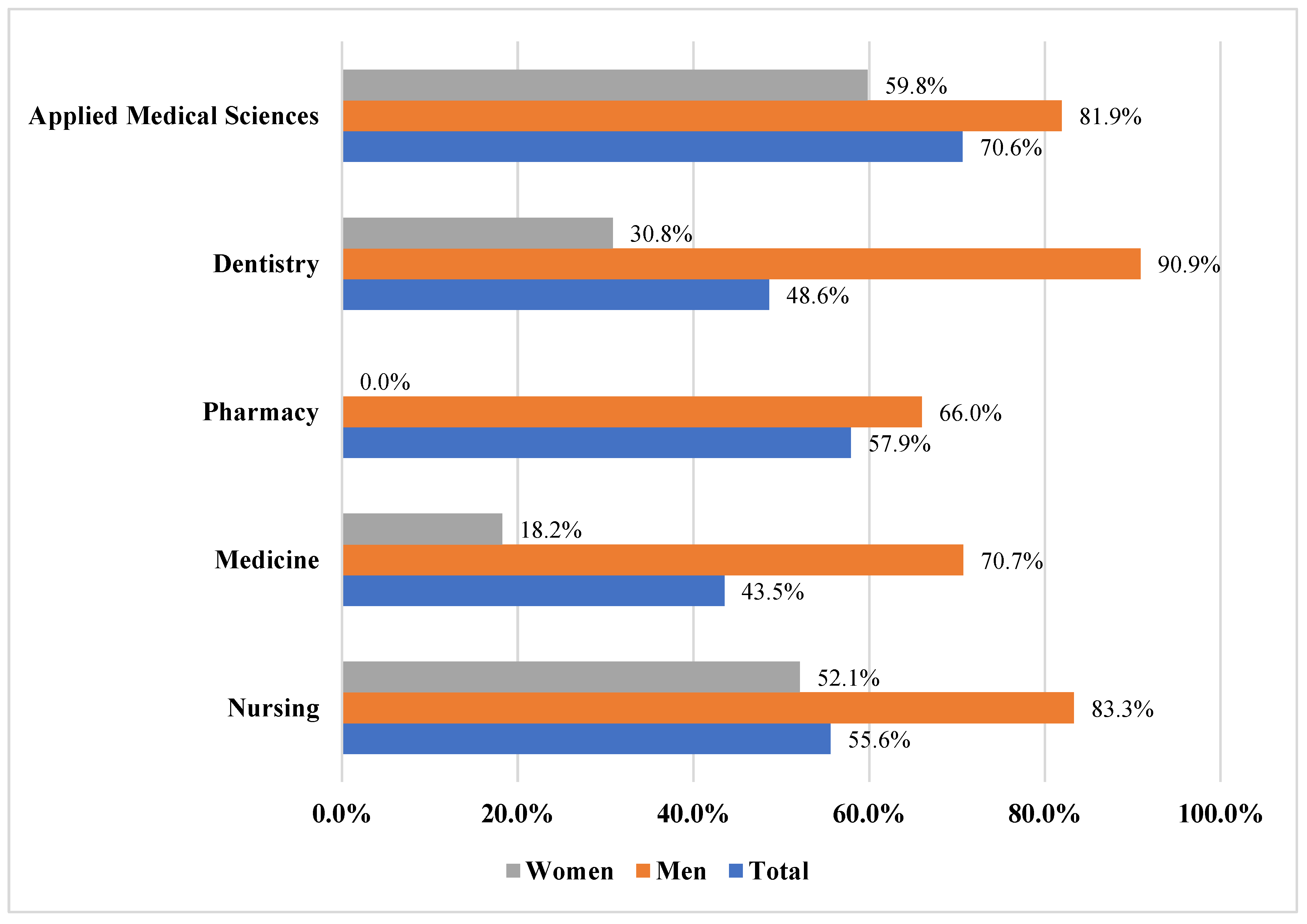

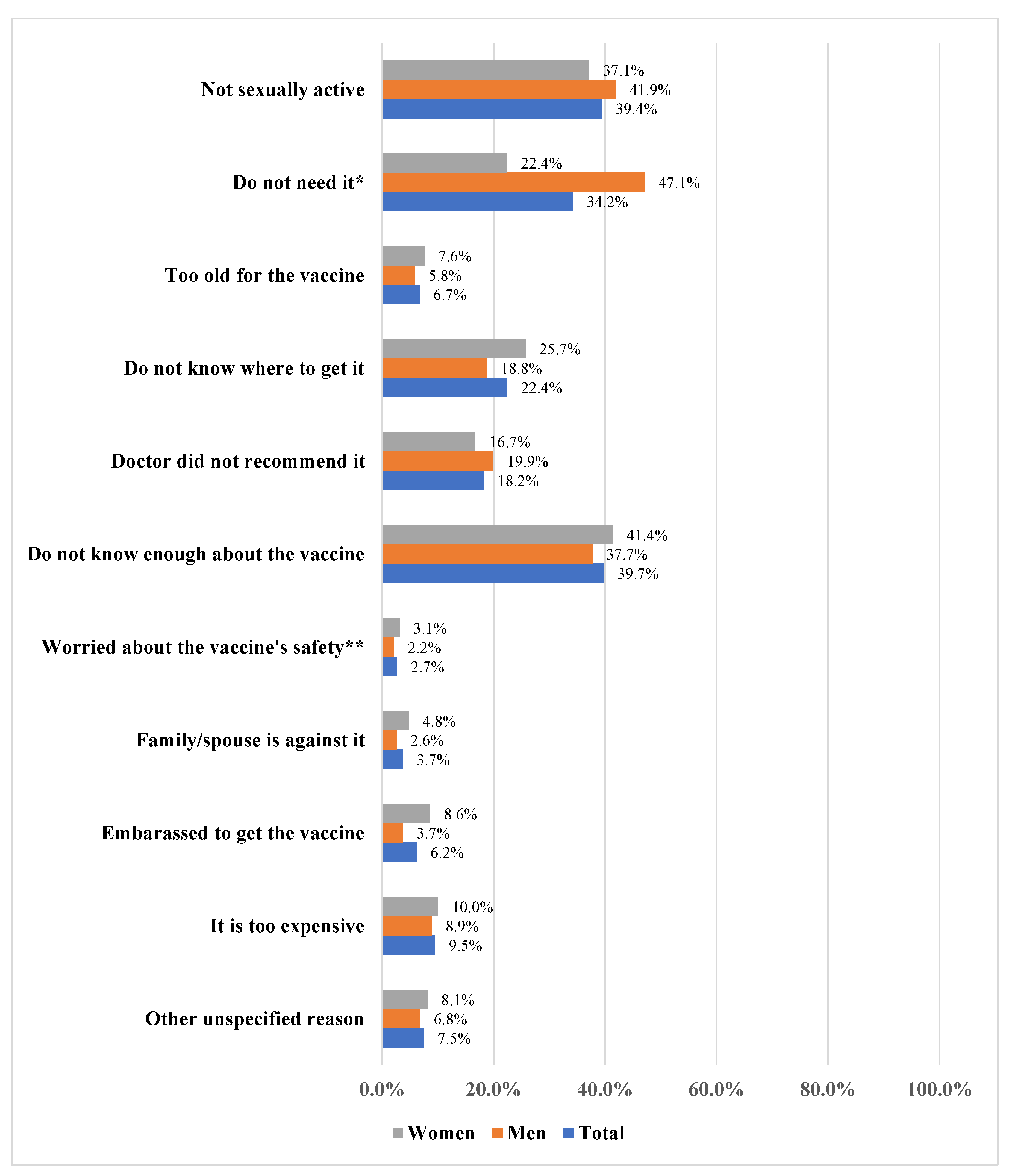

3.4. HPV Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Reasons

3.4. Predictors of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Martel, C.; Plummer, M.; Vignat, J.; Franceschi, S. Worldwide Burden of Cancer Attributable to HPV by Site, Country and HPV Type. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 664–670. [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. (Lahore). 2020, 40, 602–608. [CrossRef]

- Pimple, S.; Mishra, G. Cancer Cervix: Epidemiology and Disease Burden. Cytojournal 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Bruni L, A. G., Serrano B, Mena M, Collado Jj, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch Fx, D.S.S. Co/Iarc Information Centre on Hpv and Cancer (Hpv Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Saudi Arabia.; 2014;.

- Alhamlan, F.; Obeid, D.; Khayat, H.; Asma, T.; Al-Badawi, I.A.; Almutairi, A.; Almatrrouk, S.; Fageeh, M.; Bakhrbh, M.; Nassar, M.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Human Papillomavirus Infection on Cervical Dysplasia, Cancer, and Patient Survival in Saudi Arabia: A 10-Year Retrospective Analysis. Ann. Saudi Med. 2021, 41, 350–360. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- McLemore, M.R. Gardasil: Introducing the New Human Papillomavirus Vaccine. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2006, 10, 559–560. [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, L.E.; Tsu, V.; Deeks, S.L.; Cubie, H.; Wang, S.A.; Vicari, A.S.; Brotherton, J.M.L. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Introduction--the First Five Years. Vaccine 2012, 30 Suppl 5. [CrossRef]

- PATH Global HPV Vaccine Introduction Overview: Projected and Current National Introductions, Demonstration/Pilot Projects, Gender-Neutral Vaccination Programs, and Global HPV Vaccine Introduction Maps (2006–2023).; 2022;.

- Saudi Ministry of Health Communicable Diseases, HPV (Human Papillomavirus). Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/Diseases/Infectious/Pages/014.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) FDA Licensure of Bivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for Use in Females and Updated HPV Vaccination Recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2010, 59, 626–629.

- Kamolratanakul, S.; Pitisuttithum, P. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Efficacy and Effectiveness against Cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M.; Ali, H.; Boily, M.C.; Baldo, V.; Brassard, P.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Callander, D.; et al. Population-Level Impact and Herd Effects Following the Introduction of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Programmes: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2019, 394, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Ploner, A.; Elfström, K.M.; Wang, J.; Roth, A.; Fang, F.; Sundström, K.; Dillner, J.; Sparén, P. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1340–1348. [CrossRef]

- Loke, A.Y.; Kwan, M.L.; Wong, Y.T.; Wong, A.K.Y. The Uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Its Associated Factors among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Prim. Care Community Heal. 2017, 8, 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Saura-Lázaro, A.; Montoliu, A.; Brotons, M.; Alemany, L.; Diallo, M.S.; Afsar, O.Z.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Mosina, L.; Contreras, M.; et al. HPV Vaccination Introduction Worldwide and WHO and UNICEF Estimates of National HPV Immunization Coverage 2010-2019. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 2021, 144. [CrossRef]

- Akkour, K.; Alghuson, L.; Benabdelkamel, H.; Alhalal, H.; Alayed, N.; AlQarni, A.; Arafah, M. Cervical Cancer and Human Papillomavirus Awareness among Women in Saudi Arabia. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021, 57, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Almaghlouth, A.K.; Bohamad, A.H.; Alabbad, R.Y.; Alghanim, J.H.; Alqattan, D.J.; Alkhalaf, R.A. Acceptance, Awareness, and Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Alhusayn, K.; Alkhenizan, A.; Abdulkarim, A.; Sultana, H.; Alsulaiman, T.; Alendijani, Y. Attitude and Hesitancy of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Saudi Parents. J. Fam. Med. Prim. care 2022, 11, 2909. [CrossRef]

- Farsi, N.J.; Baharoon, A.H.; Jiffri, A.E.; Marzouki, H.Z.; Merdad, M.A.; Merdad, L.A. Human Papillomavirus Knowledge and Vaccine Acceptability among Male Medical Students in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17supp, 1968–1974. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.E.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Watson-Jones, D. Status of HPV Vaccine Introduction and Barriers to Country Uptake. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4761–4767. [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Diaz, M.; Barrionuevo-Rosas, L.; Herrero, R.; Bray, F.; Bosch, F.X.; de Sanjosé, S.; Castellsagué, X. Global Estimates of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage by Region and Income Level: A Pooled Analysis. Lancet. Glob. Heal. 2016, 4, e453–e463. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Darraj, A.I.; Arishy, A.M.; Alshamakhi, A.H.; Osaysi, N.A.; Jaafari, S.M.; Sumayli, S.A.; Mushari, R.Y.; Alhazmi, A.H. Human Papillomavirus Knowledge and Vaccine Acceptability in Jazan Province, Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, F.; Khan, K.U. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions Regarding Human Papillomavirus among University Students in Hail, Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Almehmadi, M.M.; Salih, M.M.; Al-Hazmi, A.S. Awareness of Human Papillomavirus Infection Complications, Cervical Cancer, and Vaccine among the Saudi Population: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaikh GK, Almussaed EM, Fayed AA, Khan FH, Syed SB, Al-Tamimi TN, E.H. Knowledge of Saudi Female University Students Regarding Cervical Cancer and Acceptance of the Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine - PubMed. Saudi Med J. 2014, 35, 1223–1230.

- Aldawood, E.; Alzamil, L.; Faqih, L.; Dabbagh, D.; Alharbi, S.; Hafiz, T.A.; Alshurafa, H.H.; Altukhais, W.F.; Dabbagh, R. Awareness of Human Papillomavirus among Male and Female University Students in Saudi Arabia. Healthc. 2023, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Farsi, N.J.; Baharoon, A.H.; Jiffri, A.E.; Marzouki, H.Z.; Merdad, M.A.; Merdad, L.A. Human Papillomavirus Knowledge and Vaccine Acceptability among Male Medical Students in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 1968–1974. [CrossRef]

- Waller, J.; Ostini, R.; Marlow, L.A.V.; McCaffery, K.; Zimet, G. Validation of a Measure of Knowledge about Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Using Item Response Theory and Classical Test Theory. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 2013, 56, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wu, B.; Dai, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Mei, K.; Wu, Z. Gender Differences in Knowledge and Attitude towards HPV and HPV Vaccine among College Students in Wenzhou, China. Vaccines 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Adjei Boakye, E.; Tobo, B.B.; Rojek, R.P.; Mohammed, K.A.; Geneus, C.J.; Osazuwa-Peters, N. Approaching a Decade since HPV Vaccine Licensure: Racial and Gender Disparities in Knowledge and Awareness of HPV and HPV Vaccine. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 2713–2722. [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Ren, H.; Guo, B.; Zhang, M. Have You Ever Heard of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine? The Awareness of HPV Vaccine for College Students in China Based on Meta-Analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2736–2747. [CrossRef]

- Lingam, A.S.; Koppolu, P.; Alhussein, S.A.; Abdelrahim, R.K.; Abusalim, G.S.; Elhaddad, S.; Asrar, S.; Nassani, M.Z.; Gaafar, S.S.; Bukhary, F.M.T.; et al. Dental Students’ Perception, Awareness and Knowledge About HPV Infection, Vaccine, and Its Association with Oral Cancer: A Multinational Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 3711–3724. [CrossRef]

- Farsi, N.J.; Sharif, S. Al; Qathmi, M. Al; Merdad, M.; Marzouki, H.; Merdad, L. Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Oropharyngeal Cancer and Acceptability of the HPV Vaccine among Dental Students. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 3595–3603. [CrossRef]

- Du, E.Y.; Adjei Boakye, E.; Taylor, D.B.; Kuziez, D.; Rohde, R.L.; Pannu, J.S.; Simpson, M.C.; Patterson, R.H.; Varvares, M.A.; Osazuwa-Peters, N. Medical Students’ Knowledge of HPV, HPV Vaccine, and HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, T. Human Papillomavirus and Its Vaccination: Knowledge and Attitudes among Female University Students in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. care 2020, 9, 1849. [CrossRef]

- Azer, S.A.; Alsaleem, A.; Albassam, N.; Khateeb, R.; Alessa, A.; Aljaloud, A.; Alkathiri, S. What Do University Students Know about Cervical Cancer and HPV Vaccine? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 3735–3744. [CrossRef]

- Bencherit, D.; Kidar, R.; Otmani, S.; Sallam, M.; Samara, K.; Barqawi, H.J.; Lounis, M. Knowledge and Awareness of Algerian Students about Cervical Cancer, HPV and HPV Vaccines: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Cheng, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X. HPV Vaccine Hesitancy Among Medical Students in China: A Multicenter Survey. Front. public Heal. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Alsanafi, M.; Salim, N.A.; Sallam, M. Willingness to Get HPV Vaccination among Female University Students in Kuwait and Its Relation to Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19. [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, J.A.; Comber, J.D. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection and Vaccination: A Cross-Sectional Study of College Students’ Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitudes in Villanova, PA. Vaccine X 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

| Student characteristics | College | ||||

|

Applied Medical Sciences N=170 |

Dentistry N=37 |

Pharmacy N=57 |

Medicine N=85 |

Nursing N=50 |

|

| Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | |

| Gender* | |||||

| Woman | 87 (51.2%) | 26 (70.3%) | 7 (12.3%) | 44 (51.8%) | 48 (88.9%) |

| Man | 83 (48.8%) | 11 (29.7%) | 50 (87.7%) | 41 (48.2%) | 6 (11.1%) |

| Age group* | |||||

| 18-20 years | 122 (71.8%) | 2 (5.4%) | 11 (19.3%) | 12 (14.1%) | 27 (50%) |

| 21-23 years | 42 (24.7%) | 27 (73.0%) | 43 (75.4%) | 67 (78.8%) | 25 (46.3%) |

| 24 years or older | 6 (3.5%) | 8 (21.6%) | 3 (5.3%) | 6 (7.1%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 168 (98.8%) | 36 (97.3%) | 57 (100%) | 84 (98.8%) | 50 (92.6%) |

| Married | 2 (1.2%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (5.6%) |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| GPA* | |||||

| Lower than 4 | 81 (47.6%) | 1 (2.7%) | 10 (17.5%) | 11 (12.9%) | 10 (18.5%) |

| 4 or above | 89 (52.4%) | 36 (97.3%) | 47 (82.5%) | 74 (87.1%) | 44 (81.5%) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Smoker | 24 (14.1%) | 6 (16.2%) | 7 (12.3%) | 12 (14.1%) | 6 (11.1%) |

| Non-smoker | 146 (85.9%) | 31 (83.8%) | 50 (87.7%) | 73 (85.9%) | 48 (88.9%) |

| History of STI | |||||

| Yes | 5 (2.9%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.5%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| No | 165 (97.1%) | 37 (100%) | 57 (100%) | 82 (96.5%) | 52 (96.3%) |

| Statements | Applied Medical Sciences N=41 |

Dentistry N=25 |

Pharmacy N=43 |

Medicine N=69 |

Nursing N=23 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women Count(%) |

Men Count(%) |

Women Count(%) |

Men Count(%) |

Women Count(%) |

Men Count(%) |

Women Count(%) |

Men Count(%) |

Women Count(%) |

Men Count(%) |

|

| HPV vaccine requires three doses | ||||||||||

| True | 9 (25.0%) | 0 | 6 (27.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 12 (32.4%) | 24 (66.7%) | 13 (39.4%) | 13 (61.9%) | 1 (50%) |

| False | 3 (13.9%) | 1 (20.0%) | 5 (22.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (10.8%) | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (6.1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Don't know | 22 (61.1%) | 4 (80.0%) | 11 (50.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 21 (58.8%) | 8 (22.2%) | 18 (54.5%) | 8 (38.1%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| HPV vaccine offers protection against all STIs | ||||||||||

| True | 12 (33.3%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 0 | 6 (16.2%) | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (6.1%) | 10 (47.6%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| False | 10 (27.8%) | 3 (60.0%) | 17 (77.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 6 (100%) | 22 (59.5%) | 29 (80.6%) | 30 (90.9%) | 9 (42.9%) | 0 |

| Don't know | 14 (38.9%) | 1 (20.0%) | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 | 9 (24.3%) | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| HPV vaccine is most effective if given to people who have never had sex | ||||||||||

| True | 17 (47.2%) | 3 (60.0%) | 7 (31.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (50.0%) | 10 (27.0%) | 31 (86.1%) | 19 (57.6%) | 12 (57.1%) | 0 |

| False | 4 (11.1%) | 0 | 4 (18.2%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 9 (24.3%) | 2 (5.6%) | 3 (9.1%) | 2 (9.5%) | 2 (100%) |

| Don't know | 15 (41.7%) | 2 (40.0%) | 11 (50.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 18 (48.6%) | 3 (8.3%) | 11 (33.3%) | 7 (33.3%) | 0 |

| A person who has HPV vaccine cannot develop cervical cancer | ||||||||||

| True | 6 (16.7%) | 7 (17.1%) | 7 (31.8%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 9 (24.3%) | 5 (13.9%) | 1 (3.0%) | 7 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| False | 8 (22.2%) | 9 (22.0%) | 9 (40.9%) | 2 (66.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 16 (43.2%) | 25 (69.4%) | 26 (78.8%) | 8 (38.1%) | 0 |

| Don't know | 22 (61.1%) | 25 (61.0%) | 6 (27.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 12 (32.4%) | 6 (16.7%) | 6 (18.2%) | 6 (28.6%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| HPV vaccine offers protection against most cervical cancers | ||||||||||

| True | 17 (47.2%) | 3 (60.0%) | 13 (59.1%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (50.0%) | 14 (37.8%) | 26 (72.2%) | 23 (69.7%) | 14 (66.7%) | 2 (100%) |

| False | 3 (8.3%) | 0 | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 7 (18.9%) | 2 (5.6%) | 6 (18.2%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 |

| Don't know | 16 (44.4%) | 2 (40.0%) | 8 (36.4%) | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 16 (43.2%) | 8 (22.2%) | 4 (12.1%) | 6 (28.6%) | 0 |

| One of the HPV vaccines offers protection against genital warts | ||||||||||

| True | 14 (38.9%) | 1 (20.0%) | 12 (54.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 20 (46.5%) | 27 (75.0%) | 17 (51.55) | 9 (42.9%) | 2 (100%) |

| False | 3 (8.3%) | 0 | 2 (9.1%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (11.6%) | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (3.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 |

| Don't know | 19 (52.8%) | 4 (80.0%) | 8 (36.4%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 | 18 (41.9%) | 8 (22.2%) | 15 (45.5%) | 10 (47.6%) | 0 |

| Girls who have had HPV vaccine do not need to get regular pap smears when they are older | ||||||||||

| True | 1 (2.8%) | 0 | 2 (9.1%) | 0 | 0 | 5 (13.5%) | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (3.0%) | 7 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| False | 17 (47.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | 14 (63.6%) | 0 | 4 (66.7%) | 11 (29.7%) | 24 (66.7%) | 24 (72.7%) | 10 (34.9%) | 0 |

| Don't know | 18 (50.0%) | 4 (80.0%) | 6 (27.3%) | 3 (100%) | 2 (33.3%) | 21 (56.8%) | 11 (30.6%) | 8 (24.2%) | 4 (19.0%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| Mean % of correct response (SD) | 46.9 (23.9) | 42.8 (23.6) | 55.7 (20.1) | 33.3 (21.8) | 71.4 (31.3) | 46.1 (20.4) | 75.9 (22.6) | 65.8 (22.0) | 53.6 (21.2) | 35.7 (10.1) |

| Student characteristics | Vaccine Hesitancy | |

|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | ||

| Woman | Ref | |

| Man | 6.2 | 3.44, 11.16 |

| College | ||

| Applied medical sciences | Ref | |

| Dentistry | 1.2 | 0.50, 3.14 |

| Pharmacy | 0.5 | 0.24, 1.28 |

| Medicine | 0.6 | 0.32, 1.35 |

| Nursing | 1.2 | 0.59, 2.49 |

| Age group | ||

| 18-20 years | Ref | |

| 21-23 years | 0.4 | 0.20, 0.65 |

| 24 years or older | 0.4 | 0.15, 1.17 |

| GPA | ||

| Lower than 4 | Ref | |

| 4 or above | 0.9 | 0.51, 1.67 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Smoker | 0.7 | 0.35, 1.44 |

| Non-smoker | Ref | |

| Awareness about HPV vaccine | ||

| Yes | 0.5 | 0.28, 0.83 |

| No | Ref | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).