Submitted:

05 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

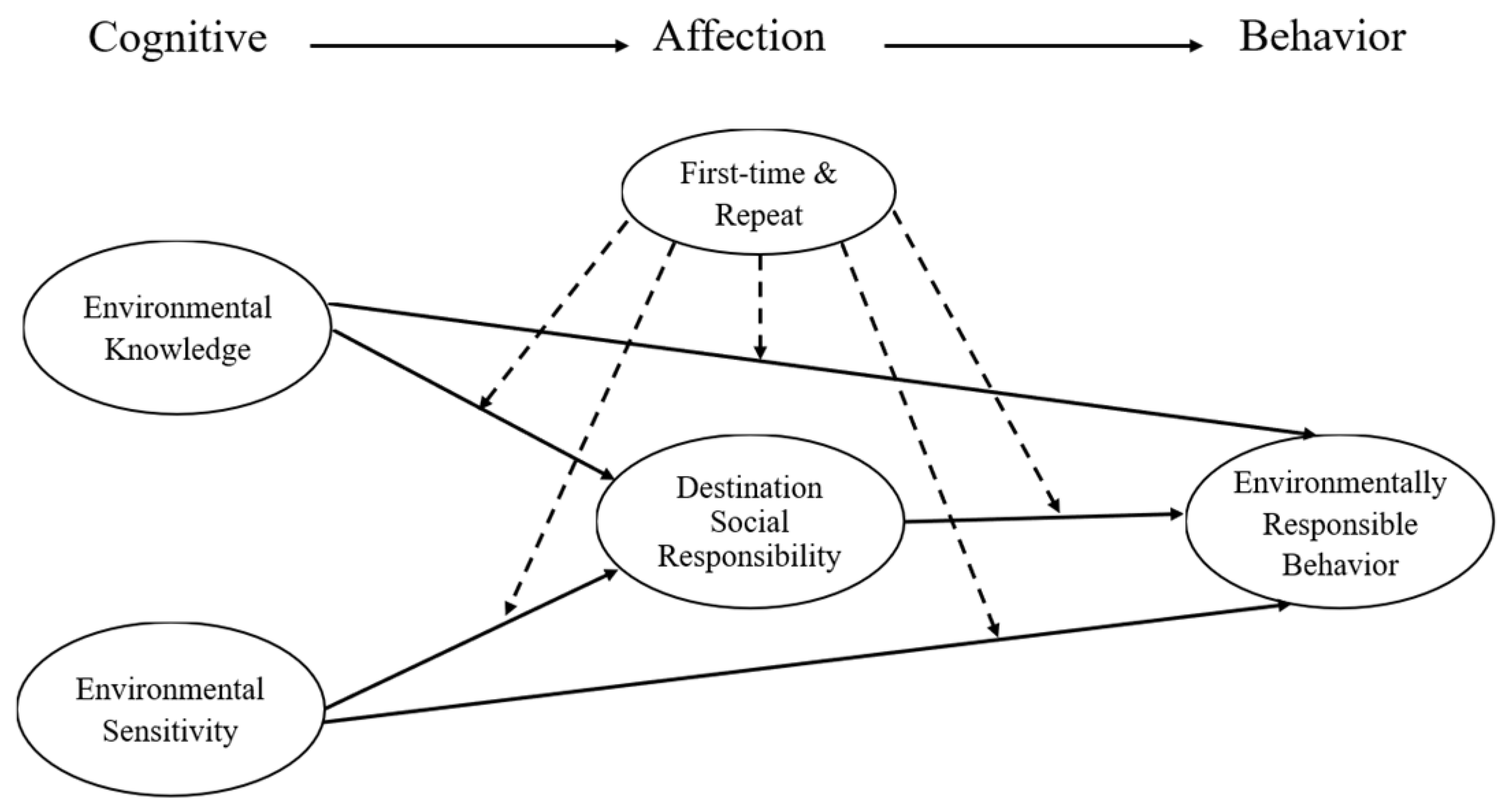

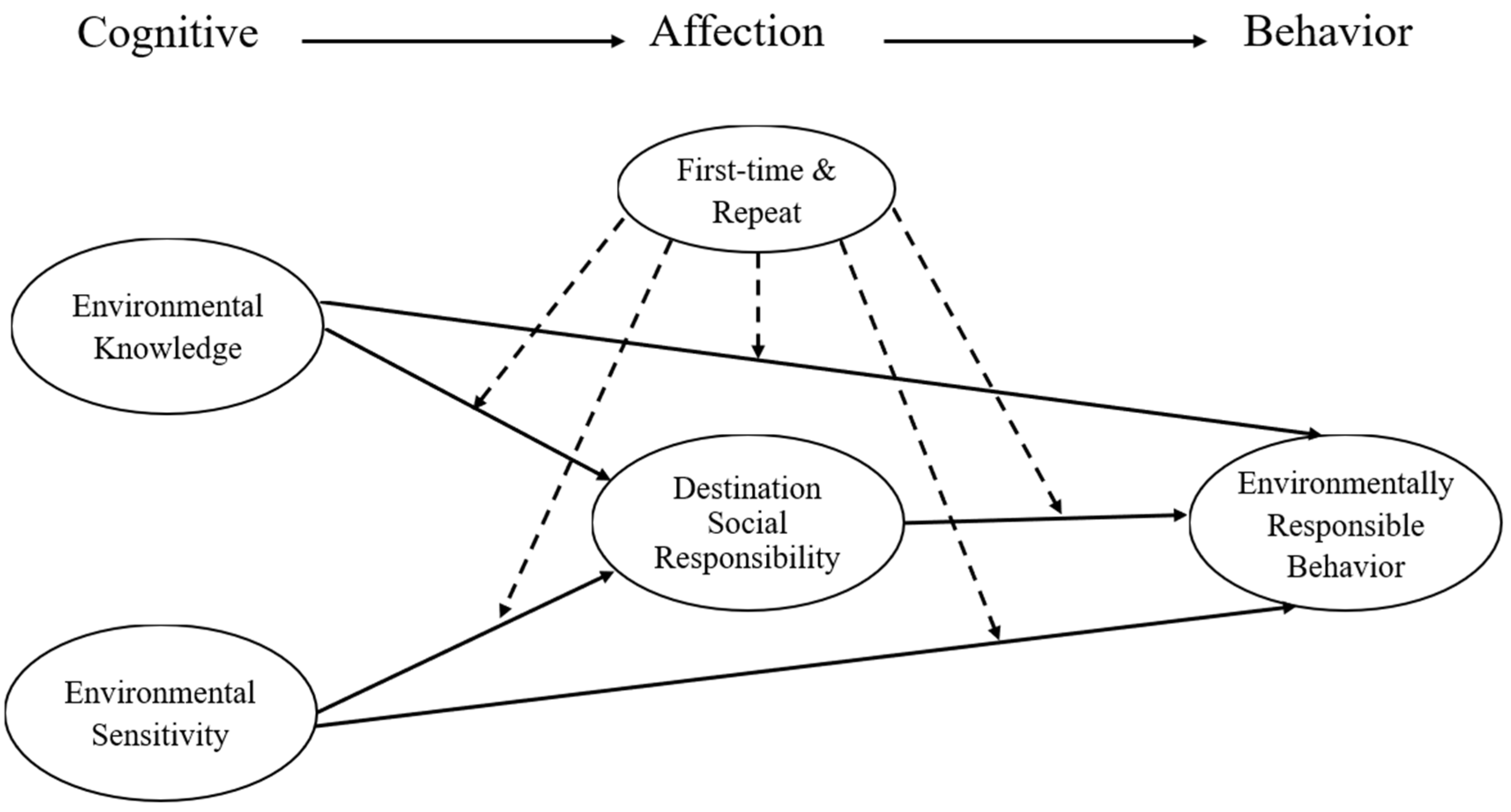

2.1. Subsection Cognition-Affect-Behavior Model

2.2. Cognition: Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Sensitivity

2.3. Affect: Destination Social Responsibility

2.4. Affect: Destination Social Responsibility Behavior: Environmentally Responsible Behaviors

2.5. Moderating Variable: First-time vs. Repeat Volunteers

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Subjects

3.3. Research Tools

3.4. Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographic Background

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

4.4. Mediating Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusion

References

- Forrest, A.; Giacovazzi, L.; Dunlop, S.; Reisser, J.; Tickler, D.; Jamieson, A.; Meeuwig, J.J. Eliminating plastic pollution: How a voluntary contribution from industry will drive the circular plastics economy. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2019, 6, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassignet EP, Xu X, Zavala-Romero O. Tracking marine litter with a global ocean model: Where does it go? Where does it come from? Frontiers in Marine Science. 2021, 8, 667591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Stegeman, J.J.; Fleming, L.E.; Allemand, D.; Anderson, D.M.; Backer, L.C.; Brucker-Davis, F.; Chevalier, N.; Corra, L.; Czerucka, D. Human health and ocean pollution. Annals of global health. 2020, 86, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dripfina. 100+ Frightening Plastic in The Ocean Statistics And Facts 2021-2022. 2022 01 August. Available from: https://dripfina.com/plastic-in-the-ocean-statistics/.

- Volunteer World. Volunteer Scuba Diving Projects. 2022 01 August. Available from: https://www.volunteerworld.com/en/volunteer-abroad/diving.

- Overseas. Marine Conservation Volunteering & Scuba Diving in Caribbean Sea. 2022 01 Auguest. Available from: https://www.gooverseas.com/volunteer-abroad/grenada/program/257154.

- Clean Up the Lake The 72 Mile Clean, Up. 2022 22 August. Available from: https://cleanupthelake.org/.

- Greenpeace. Stay together with our ocean. 2022 2022 Auguest. Available from: https://www.greenpeace.org/taiwan/.

- Cerrano, C.; Milanese, M.; Ponti, M. Diving for science-science for diving: volunteer scuba divers support science and conservation in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 2017, 27, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Graefe, A.R.; Meyer, L.A. Specialization and marine based environmental behaviors among SCUBA divers. Journal of Leisure Research. 2006, 38, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J Environ Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. Journal of Sustainable tourism. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-S.; Shih, L.-H. Effective environmental management through environmental knowledge management. Int J Environ Sci Technol (Tehran). 2009, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, C. The effects of environmental education on the behavior of divers: A case study from the British Virgin Island. London: The University of Greenwich; 2000. Master.

- Chawla, L. Significant life experiences revisited: A review of research on sources of environmental sensitivity. The Journal of environmental education. 1998, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of destination social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceived quality of life. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2016, 42, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of management. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira MR, Proença JF, Rocha M. Do occasional volunteers repeat their experience? Journal of Human Values. 2016, 22, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerkin, R.M.; Swiss, J.E. Religious motivations and social service volunteers: The interaction of differing religious motivations, satisfaction, and repeat volunteering. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 2013, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Batra, R. Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. J Cons Res. 1987, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X. Landscape and unique fascination: a dual-case study on the antecedents of tourist pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Land. 2022, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M. Land Issues and Their Impact on Tourism Development. MDPI; 2022. p. 658.

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-H.; Korfiatis, N.; Chang, C.-T. Mobile shopping cart abandonment: The roles of confli cts, ambivalence, and hesitation. J Bus Res. 2018, 85, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.Y.; Kim, K.; Stout, P.A. Assessing the effects of animation in online banner advertising: Hierarchy of effects model. Journal of interactive advertising. 2004, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Goudeau, C. Consumers’ beliefs, attitudes, and loyalty in purchasing organic foods: The standard learning hierarchy approach. Br Food J. 2014, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J.E. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: a cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological bulletin. 2007, 133, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Perceived quality and service experience: Mediating effects of positive and negative emotions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. 2019, 28, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. The effect of Flemish eco-schools on student environmental knowledge, attitudes, and affect. IJSEd. 2011, 33, 1513–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Kim, J.; Thapa, B. Influence of environmental knowledge on affect, nature affiliation and pro-environmental behaviors among tourists. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environmental Education Research. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, A.; Skrzypiec, G. Environmental attitudes of senior secondary school students in South Australia. Global Environ Change. 1998, 8, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.R.; Volk, T.L. Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The journal of environmental education. 1990, 21, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Tuou, Y.; Liu, J. How does destination social responsibility impact residents’ pro-tourism behaviors? The mediating role of place attachment. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.S.; Pearce, J. How does destination social responsibility contribute to environmentally responsible behaviour? A destination resident perspective. J Bus Res. 2018, 86, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time & repeat tourists. Tourism Management. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.A.T.; Hwang, Y.S.; Yu, C.; Yoo, S.J. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourists’ satisfaction: The mediating role of emotions. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Khan, H.U.R.; Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Ahmed, M.F. Sustainable Tourism Policy, Destination Management and Sustainable Tourism Development: A Moderated-Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. The Journal of environmental education. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Hsu, M.K.; Boostrom Jr, R.E. From recreation to responsibility: Increasing environmentally responsible behavior in tourism. J Bus Res. 2020, 109, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller T, Dolnicar S, Leisch F. The sustainability–profitability trade-off in tourism: can it be overcome? Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2011, 19, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, F.M. Structural Equation Modeling. Taipei, Taiwan: Wu-Nan Book Inc; 2009.

- Kim, H.; Millsap, R. Using the Bollen-Stine bootstrapping method for evaluating approximate fit indices. Multivariate behavioral research. 2014, 49, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saputra, F.E.; Putra, W.H. An Implication of Destination Attractiveness, Environmental Sensitivity, and Satisfaction with Interpretive Service on Place Attachment and Environmental Responsible Behavior. International Journal of Social Science and Business. 2020, 4, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustinx, L. I quit, therefore I am? Volunteer turnover and the politics of self-actualization. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2010, 39, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolford, M.; Cox, K.; Culp, I.I.I.K. Effective Motivators for Master Volunteer Program Development. Journal of extension. 2001, 39, n2. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Item |

|---|---|

| Environmental knowledge | 1. Maintaining ecological balance contributes to sustainable marine development (EK1). 2. It is for the next generation that we must protect marine natural resources (EK2). 3. Maintaining species diversity contributes to marine ecological balance (EK3). 4. Excessive use of natural resources will destroy the sustainable development of the ocean (EK4). 5. Excessive diving activities will cause damage to the marine environment (EK5). 6. Carbon dioxide emitted by vehicles will increase the temperature of the seawater (EK6). 7. Excessive development of marine tourism will erode marine natural resources (EK7). 8. The use of disposable products can cause harm to the marine environment (EK8). |

| Environmental sensitivity | 1.I like the natural marine environment (ES9). 2.I am concerned about the development of marine environmental conservation (ES10). 3.I appreciate the natural marine environment (ES11). 4.I care about the impact of my living habits on the marine environment (ES12). |

| Destination social responsibility | 1.I think it is my duty to maintain the marine environment (DSR13). 2.I think maintaining the marine environment is an important mission (DSR14). 3.I am willing to maintain the marine environment to promote local community development (DSR15). 4.I am willing to maintain the marine environment to promote the development of the local marine economy (DSR16). 5.I am willing to maintain the marine environment to promote the sustainable development of the destination (DSR17). |

| Environmentally responsible behavior | 10. I will learn how to solve marine environmental problems (ERB18). 11. I will read national ocean reports, publicity, or books (ERB19). 12. I will discuss with others issues related to marine environmental protection (ERB20). 13. I will try to persuade my fellow travelers to take actions that are beneficial to the marine natural environment (ERB21). 14. When I see others destroying the marine environment, I will report it to the relevant authorities (ERB22). 15. I will follow the legal approach to stop the destruction of the marine environment (ERB23). 16. Usually, when I see litter in the ocean, I will pick it up on my own initiative (ERB24). 17. I will participate if there are activities related to cleaning up marine waste (ERB25). |

| Variable | Item | Q’ty of samples | Percentage (%) | Accumulative percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 178 | 59.3 | 59.3 |

| Female | 122 | 40.7 | 100.0 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 210 | 70.0 | 70.0 |

| Married | 90 | 30.0 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 20 years old (including) and below | 23 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| 21-30 years old | 84 | 28.0 | 35.7 | |

| 31-40 years old | 90 | 30.0 | 65.7 | |

| 41-50 years old | 75 | 25.0 | 90.7 | |

| 51 years old (including) and above | 28 | 9.3 | 100.0 | |

| Senior and vocational high school (including) and below | 36 | 12.0 | 12.0 | |

| University/junior college | 208 | 69.3 | 81.3 | |

| Graduate school (including) and above | 56 | 18.7 | 100.0 | |

| Occupation | Students | 58 | 19.3 | 19.3 |

| Military personnel, police personnel, civil servants, and teachers | 39 | 13.0 | 32.3 | |

| Business | 50 | 16.7 | 49.0 | |

| Freelance | 21 | 7.0 | 56.0 | |

| Agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and animal husbandry | 36 | 12.0 | 68.0 | |

| Homemaker | 35 | 11.7 | 79.7 | |

| Service industry | 51 | 17.0 | 96.7 | |

| None (including retired) | 10 | 3.3 | 100.0 | |

| Current residence | Northern Taiwan | 153 | 51.0 | 51.0 |

| Central Taiwan | 39 | 13.0 | 64.0 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 62 | 20.7 | 84.7 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 25 | 8.3 | 93.0 | |

| Offshore islands | 21 | 7.0 | 100.0 | |

| Frequency of participation | 1 time | 140 | 46.7 | 46.7 |

| 2 times | 64 | 21.3 | 68.0 | |

| 3 times (including) and more | 96 | 32.0 | 100.0 |

| Potential variables | Observed variables | Factor loadings | Cronbach‘s alpha | Construct reliability | Average variance extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental knowledge | EK 1 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.71 |

| EK 2 | 0.85 | ||||

| EK 3 | 0.92 | ||||

| EK 4 | 0.81 | ||||

| EK 8 | 0.71 | ||||

| Environmental sensitivity | ES 1 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.78 |

| ES 2 | 0.77 | ||||

| ES 3 | 0.94 | ||||

| Destination social responsibility | DSR1 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.78 |

| DSR2 | 0.92 | ||||

| DSR3 | 0.86 | ||||

| DSR5 | 0.86 | ||||

| Environmentally responsible behavior | ERB1 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.73 |

| ERB3 | 0.88 | ||||

| ERB4 | 0.84 | ||||

| ERB7 | 0.74 |

| Mediating variable | Causal relationship | First-time (β value) | Repeat (β value) | z-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-time & repeat volunteers | Environmental knowledge-> Destination social responsibility | 0.78* | 0.92* | 0.86 |

| Environmental sensitivity-> Destination social responsibility | 0.25* | 0.17 | -0.55 | |

| Environmental knowledge-> Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.45* | -0.04 | -1.88* | |

| Environmental sensitivity-> Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.01 | 0.43* | 2.59* | |

| Destination social responsibility-> Environmentally responsible behaviors | 0.67* | 0.58* | -0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).