1. Introduction

Quality of life (QOL), as an essential dimension of human existence, has always been accepted as the ultimate goal of healthcare [1, 2]. However only in modern times has the debate progressed beyond philosophy and onto the implementation of specific interventions and measures directed at health-related quality of life. It is generally accepted that the modern era of the ‘quality of life’ concept debuted through the efforts of the World Health Organization (WHO) [

2], which expanded the definition of health to mean “not only the absence of infirmity and disease, but also a state of physical, mental, and social well-being” [

3].

The WHO definition not only put health in a more holistic context, but also laid the foundations for operationalizing quality of life as a genuine measure of wellbeing. This meant that the measures of health went beyond the established clinical or biological outcomes (symptoms, signs, clinical events), and approached more personal domains (such as perception of the treatment, self-image and distress caused by cancer) [

4].

QOL is a multidimensional construct that consists of several domains, among which are physical, mental and social ones [

4]. While there is agreement among the many definitions of QOL, there are also differences. The 1995 WHO definition of QOL was “individuals' perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”. QOL was referred to as the individual’s satisfaction with life and perception of wellbeing by Schumaker et al. (1990) [

5]. Oleson (1990) [

6] defines QOL as the subjective perception of satisfaction or happiness in the relevant domains of the individual. Revicki (2000) [

7] suggests QOL represents “a broad range of human experiences related to one's overall well-being”. Other authors have looked at a narrow definition that is more directly related to the health of the individual. For instance, Csaba et al. (2015) [

8] recognize two fundamental components of QOL. First is the ability to execute daily activities, referring to physical, psychological and social wellbeing (individual’s perception of their own condition). The second component refers to the degree of satisfaction regarding one’s level of functionality and control capacity in symptom evaluation and treatment [

9]. The latter component, that health research usually refers to as ‘health-related quality of life’ is the focus of this review. In the interest of convenience, we will refer to this concept as QOL. When considering QOL specifically in cancer patients, Cella and Tulsky (1993) [

10] suggest it describes “patients’ appraisal of and satisfaction with their current level of functioning compared to what they perceive to be possible or ideal”.

2. Materials and Methods

Studies included in the review consisted of published English language peer-reviewed articles focused on examining current psycho-oncological approach guidelines and their relationship with the Romanian policy. We utilized the following databases: Google Scholar, Elicit, PsycINFO, PubMed and Science Direct and conducted electronic searches from March 2023 to April 2023, examining articles published at any time prior to March 15, 2023. Searches were conducted with terms related to Psycho-Oncology (i.e., “psycho-oncology,” “oncology,” “psychosocial”, „psycho-oncology guidelines,” “cancer patients” or “Romania”) and quality of life (i.e., “life quality,” “health-related quality of life,” “quality of life indicators”). The concept of „quality of life and „Romanian Psycho-Oncology” were very scarcely mentioned throughout literature thus we included broader concepts like „Eastern Europe Psycho-Oncology”, „Eastern Europe quality of life in cancer patients” to attain a broader perspective on our primary objectives. All published articles found using the above search terms and deemed to be related to the topic of focus were included based on their relevance.

3. Considerations and Models of Health-Related Quality of Life

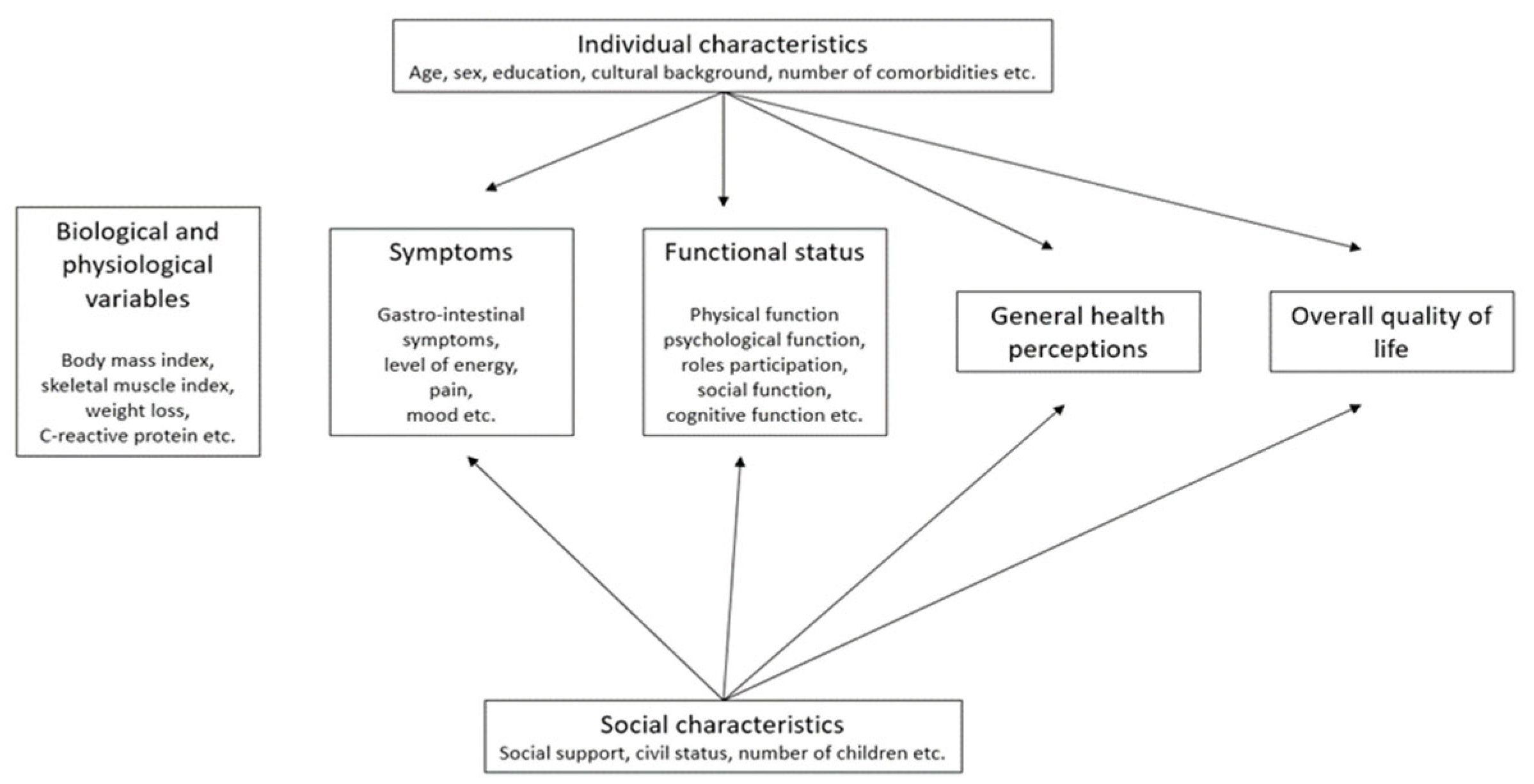

To map out existing conceptual relationships within elements of QOL, Wilson and Cleary (1995) [

11] proposed a conceptual model, a version of which is presented in

Figure 1. The novelty of this model is that it connects two aspects of research, clinical and social, as well as provides a visualization of the biological, clinical, physical, psychological and social factors influencing the quality of life. This model has been adopted by many authors and adapted to better allow that targeting of specific QOL measurement tools [

9].

4. The need to Assess QOL in Cancer Patients

Jenkins (1992) [

12] argues that QOL is a critical component of health care, as “the ultimate purpose of all health interventions is to enhance the quality of life”. Consequently, QOL assessment should be considered in all evaluations of health interventions.

The issue that Jenkins (and many other authors since) raises is that, although “people are the best experts on themselves” [

13] and patients’ perceptions are valid signs of QOL, when assessing QOL, it is necessary to rely as much as possible on observable phenomena and objective psychometric instruments, rather than subjective self-ratings. This is because much of the subjective perception of health is based on the patient’s expectations (e.g., a patient not expecting a full recovery may exhibit a high satisfaction for only partial satisfaction) [

12].

The English National Health Service (NHS) conducts an ongoing survey on the QOL of patients diagnosed with cancer [

14]. Its aim is to explore the QOL changes for cancer patients, to assess the service provision. The data collected as part of the survey helps to better understand unmet needs. The survey results are reported in an interactive format, including several aspects of QOL, including health (such as mobility), functional domains (such as emotional) and symptoms (such as fatigue) [

14]. In the September 2022 update, the survey reported that cancer patients reported a mean QOL level of 74.3, significantly lower (p<0.001) than the 81.8 level reported in the general population [

15]. The cancer patients also reported significantly more problems than the general population for all aspects of health (p<0.001 each aspect). This difference was largest for usual activities. 48.5% of cancer patients reported having mental health problems, compared with 33.1 in the general population. The Cancer QOL survey [

14] is currently one of the most important tools to influence health policy, professional practice and to enable patient empowerment in the United Kingdom.

QOL assessment is getting more emphasis all around the globe. The International Psycho-Oncology Society (IPOS) functions as a multidisciplinary organization dedicated to promoting evidence-based approaches in psychosocial and behavioral oncology for the improvement of care in cancer patients [

16]. The most recent IPOS standard of care, supported by many organizations worldwide, includes three core principles: 1) Psychosocial cancer care should be recognized as a universal human right; 2) Quality cancer care must integrate the psychosocial domain into routine care; 3) Distress should be measured as the sixth vital sign [

16].

It has long been argued that impact on QOL should be an important outcome to include in all clinical trials of health interventions, even as early as the regulatory step [

17]. However, this had proven more difficult to implement in practice, due to many reasons presented, but mainly due to the lack of a universal QOL measure that could be applicable in every clinical context.

Because of this methodological constraint, the United States Food and Drug Administration explicitly accepts surrogate outcomes instead of QOL outcomes when evaluating anti-cancer treatments [

18], while the European Medicines Agency (EMA) advises care in using QOL outcomes and, more generally, patient-reported outcomes. In addition, even when the QOL measuring instruments are sufficiently validated, there is a concern that not all relevant domains are appropriately reported [

19].

4.1. The Regional Context

In 2021, the European Union (EU) launched Europe's Beating Cancer Plan [

20], a new EU-wide approach to prevention, treatment and care of cancer, focusing on areas where the European perspective would add the most value. This plan was structured around 10 key European initiatives to tackle all parts of the disease pathway. The European Commission allocated around €4 billion for these actions, from sources including the EU4Health program, Horizon Europe and the Digital Europe program. This included prevention, early detection and improved diagnosis and treatment for cancer patients across EU.

One of the actions specifically aims to improve the quality of life for cancer patients and survivors. Entitled 'Better Life for Cancer Patients Initiative', this initiative will focus on follow-up care. The aim is to provide a 'Cancer Survivor Smart-Card' that can summarize patients' clinical history and facilitate and monitor follow-up care. An European Cancer Patient Digital Centre will also be launched to support the exchange of patients' data and the monitoring of survivors' health conditions [

20].

Another key initiative of the Cancer plan was the European Cancer Inequalities Registry. The aim of this registry is to provide reliable data on disparities between EU Member States and regions [

20]. Part of this initiative was the drawing up of country cancer profiles in collaboration with The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [

21].

4.2. The Romanian Context

The Romanian Cancer profile [

21] reports a cancer mortality above the EU average, which has increased for six types of cancer since 2000. Authors attribute this to possibly suboptimal performance in screening and early detection as well as “the scarcity of specialized professionals, uneven distribution of diagnostic and treatment facilities across the country, and lack of uniformity in following the protocols”. [

21]

At the end of 2022 the Cancer Prevention and Treatment Law [

22] was adopted by the Romanian Parliament. This law laid out the National Cancer Plan for 2023-2030, the current main policy document for all national actions related to cancer prevention and treatment. The plan specifically mentions the health services that Romanian citizens are entitled to. These include prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer; cancer care, including palliative care; psycho-oncology, cancer nutrition and fertility services; and social assistance. More of the plan’s details and actions will be set out in a regulation document, which is imminently being drafted by the Romanian Government.

Within the General Aim 4 of the Plan, Cancer Care, one of the current challenges is acknowledged: Romania is confronted with a critical deficit of psycho-oncology services, as well as professionals. There is currently no standard for specific counselling for cancer patients regarding their feelings. As such, the Plan recommends a standard for psycho-oncologic counselling for cancer patients and their families and monitors their quality of life. The country profile for Romania [

21] also places the cancer care performance below the EU average and unequally distributed.

As an answer to these challenges, a national recovery and resilience plan [

23] was enacted to support policy and infrastructure reform. Disease registries were also planned, including for cancer, as a priority domain. This creates an opportunity to look at integrating psycho-oncologic services into the service package for cancer patients. Psychosocial factors play an important role in the evolution of cancer and can have a favorable or negative impact on disease outcomes [

8]. According to Csaba 2015 [

8] psycho-oncology, as a multidisciplinary research and practice field, is still in its infancy in Romania.

5. Measuring Quality of Life in Cancer Patients—Tools and Psychological Interventions

5.1. Psychological Tools

Several scales have been developed for the measurement of the impact of health care on QOL. Developing a scale that can accurately measure the QOL of cancer patients is a long and complicated process. Most scales are presented as questionnaires. Many QOL scales are specific, applying to certain conditions, populations, or functional issues. Others are generic. The generic tools are more useful when measuring QOL in people with comorbidities or when evaluating complex interventions [

24]. Some generic scales include health profiles, which generate scores in several domains, and health utility measures, which generate a single score of QOL such as a quality-adjusted life-year [

24].

One such generic questionnaire is the Medical Outcome Study,36-item short-form (SF-36) [

25]. Composed of 36 items, it allows the evaluation of QOL of any population, related to eight domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, mental health).

Among the population-specific questionnaires, the Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30) [

26], developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), includes five function domains (physical, emotional, social, role, cognitive), eight symptoms (fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, insomnia, dyspnea, and appetite loss), as well as global health/quality-of-life and financial impact [

16]. Another widely used questionnaire is Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) [

27]; FACT-G explores four domains of QOL in cancer patients: physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being.

A few cancer site-specific scales have been developed by the EORTC [28, 29]. Among these, QLQ-H&N35 [

30] for head and neck cancers, QLQ-BR23 [

31] for breast cancer and QLQ-OV28 [

32] for ovarian cancer. Some questionnaires evaluate a single symptom; for instance, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Anemia (FACT-An) [

27] was developed specifically for patients with anemia. The FACT-An is composed of the FACT-G, the Fatigue Subscale and seven additional miscellaneous non-fatigue items relevant to anemia in cancer patients.

In 2014, the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI®) questionnaire [

33] was validated for Romania. The QOLI was developed as a measure of wellbeing, positive health, and meaning. Its results are generally easy to understand and immediately suggest areas for intervention [

33].

Another argument for using this tool is the measure of life satisfaction across a number of areas said to comprise human happiness and contentment (after considering genetic contributions). These sixteen areas of life are: Goals and Values, Self-Esteem, Health, Relationships (in four areas: Friends, Love, Children, and Relatives), Work and Retirement, Play, Helping or Service, Learning, Creativity, Money or standard of living, and Surroundings (Home, Neighborhood, and Community). Respondents rate how important each of the 16 domains is to their overall happiness and satisfaction.

The usefulness of the QOLI relies on the possibility of both planning and evaluating the benefit of both clinical and psychological interventions [

34]. The QOLI has been found to be sensitive to change in studies of positive psychology coaching [

35] and in studies of psychotherapy and medication effectiveness [33-35].

5.2. Psycho-Oncologic Interventions and Their Effect on the Quality of Life of Patients with Cancer

Many psychological interventions have been proposed for improving the QOL of patients with cancer. Such interventions range from short, nurse-led relaxation sessions to hour-long individual or group sessions led by a specially trained therapist [

36]. In their 2002 systematic review, looking at these interventions, Newell et al. [

36] observed that those interventions involving structured or unstructured counselling, as well as and guided imagery seem to be effective for improving patients’ general functional ability or quality of life. Follow-up evidence also suggested the benefits would persist mid to long term [

36].

The persistence of long-term effects of psycho-oncologic interventions was confirmed in a more recent meta-analysis by Faller et al. 2013 [

37]. According to their meta-analyses, interventions such as individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, psychoeducation, as well as relaxation training, produced small-to-medium effects on emotional distress, anxiety, depression, and QOL. The interventions seemed to be the most effective for patients with increased distress levels [

37].

5.3. Structure of a Psycho-Oncologic Intervention

Psycho-oncologic interventions can be heterogeneous in concept, structure and duration. We will, however, use an existing such intervention as an example of current developments in the psycho-oncology practice.

The Quality-of-Life Therapy (QOLT) was developed as a companion to QOLI, building on the evidence gathered as part of the psychometric evaluation of QOLI [

13]. QOLT is a comprehensive, individually tailored package of positive psychology interventions suitable for both coaching and use in clinical contexts [

13]. QOLT includes techniques for the control of negative feelings, making it a good match for the psycho-oncology context. QOLT patients are taught strategies and skills to help them identify, pursue and fulfil their most cherished needs [

38].

According to the QOLT theory, a person’s satisfaction with a particular area of life is made up of four parts: “(1) the objective characteristics or circumstances of an area, (2) how a person perceives and interprets an area’s circumstances, (3) the person’s evaluation of fulfilment in an area based on the application of standards of fulfilment or achievement, and (4) the value or importance a person places on an area regarding his or her overall happiness or well-being” [

13]. This model is described by the acronym “CASIO” (“Characteristics”, “Attitude about”, “Standards of fulfilment”, “Importance”), where the last letter represents “Overall satisfaction”. QOLT always involves a two-track approach in which core techniques are combined with evidence-based elements of cognitive therapy.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The evaluation of QOL in cancer patients is increasingly considered as a mandatory step in this complex health intervention. Measuring of the QOL not only reflects the impact of the medical and pharmacological treatment, but also the general wellbeing of the patient; this can suggest further areas of psycho-oncologic intervention. Unfortunately, this emerging practice is still at an early stage in Romania.

A cancer diagnosis has a long-term impact on the QOL of patients [

39]. However, much of the interaction between patients and oncologists is focused on physical symptoms and clinical signs, while general wellbeing and QOL are perceived as lesser outcomes that would improve simply by following the prescribed therapy. However, the psychological factor is important in how patients cope with the disease and may represent an untapped resource for reducing patients’ distress [

40]. The inclusion of the psycho-oncologist as part of the mixed team can facilitate the treatment process by changing the focus to more patient relevant outcomes.

There are methodological and epistemic concerns surrounding the concept of QOL. In particular, the measurement of QOL is subject to considerable methodological uncertainty, due to the necessary extrapolation of subjective outcomes into objective measurements. Currently, despite significant practice and evidence building up over time, there are no universally applicable measurement tools for QOL.

Another current challenge is the heterogeneity of QOL research in cancer. Some areas (e.g. breast [

41], colorectal [4, 42]) were disproportionately more investigated than others (e.g. male patients with cancer [

37]). More research on these aspects should provide a better understanding of the area’s most sensible to QOL interventions.

Finally, psycho-oncologic interventions take many forms and information on their effectiveness is still limited [

36]; the evidence does seem to suggest that patients with the worst QOL indicators seem to benefit the most, and the benefits seem to persist long term [

37].

On a regional level, the new health policy developments in Romania should open the way for better coordination between clinical and psychological evaluations and interventions in patients with cancer, with the potential to improve QOL and wellbeing of such patients in order for the country to better adapt to EU requirements for improving patients and caregivers cancer experience and overall quality of life as Romania will have access to the financial tools in order to attain this national objective.

Author Contributions

CGI and ML contributed to the conception, structure of the paper, contributed to analysis, and interpretation of available literature. CGI and SP contributed to the development initial draft. ML reviewed and critiqued the output for important intellectual content. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tengland, P.-A. The goals of health work: Quality of life, health and welfare. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 2006, 9, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, L. Quality of life: conceptual and measurement issues. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1992, 17, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. The first ten years of the World Health Organization; World Health Organization: 1958.

- Dunn, J.; et al. Quality of life and colorectal cancer: a review. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 2003, 27, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumaker, S.; Anderson, R.; Czajkowski, S. Psychological tests and scales. In Quality of life assessments in clinical trials; Raven Press: New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oleson, M. Content validity of the Quality of Life Index. Applied nursing research: ANR 1990, 3, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revicki, D.A.; et al. Recommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labeling and promotional claims in the United States. Quality of Life Research 2000, 9, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csaba, D.L. Aspecte psihosociale ale bolilor tumorale. Evaluare şi intervenţie. 2015: Dr. Dégi László Csaba.

- Ferrans, C.E. Definitions and conceptual models of quality of life. Outcomes assessment in cancer: Measures, methods, and applications, 2005: p. 14-30.

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S. Quality of Life in Cancer: Definition, Purpose, and Method of Measurement. Cancer Investigation 1993, 11, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: a conceptual model of patient outcomes. Jama 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.D. Assessment of outcomes of health intervention. Social Science & Medicine 1992, 35, 367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.B. Quality of life therapy: Applying a life satisfaction approach to positive psychology and cognitive therapy; John Wiley & Sons: 2005.

- National Health Service. National Health Service Cancer Quality of Life Survey. 2022 [cited 2023; Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mi-cancer-quality-of-life-survey.

- Frobisher, C.; et al. P25 A new England-wide survey on quality of life after cancer. 2022, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

- Travado, L.; et al. 2015 President's Plenary International Psycho-oncology Society: psychosocial care as a human rights issue—challenges and opportunities. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Temple, R. Food and Drug Administration requirements for approval of new anticancer drugs. Cancer treatment reports 1985, 69, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Grigore, B.; et al. Surrogate endpoints in health technology assessment: an international review of methodological guidelines. Pharmacoeconomics 2020, 38, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Europe's Beating Cancer Plan. 2021.

- European Commission, EU Country Cancer Profile: Romania 2023, in European Cancer Inequalities Registry. 2023.

- Parlamentul Roman, Legea nr. 293/2022 pentru prevenirea și combaterea cancerului. 2022.

- Marin Mileusnic, Romania's National Recovery and Resilience Plan, European Parliamentary Research Service, Editor. 2023.

- Hand, C. Measuring health-related quality of life in adults with chronic conditions in primary care settings: Critical review of concepts and 3 tools. Canadian Family Physician 2016, 62, e375–e383. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care 1992, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprangers, M.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer approach to quality of life assessment: guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. Quality of Life Research 1993, 2, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, M.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer approach to developing questionnaire modules: an update and overview. Quality of Life Research 1998, 7, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; et al. Performance of the EORTC questionnaire for the assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients EORTC QLQ-H&N35: a methodological review. Quality of Life Research 2013, 22, 1927–1941. [Google Scholar]

- El Fakir, S.; et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire-BR 23 breast cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire: psychometric properties in a Moroccan sample of breast cancer patients. BMC research notes 2014, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, A.; et al. Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer questionnaire module to assess the quality of life of ovarian cancer patients in clinical trials: a progress report. European Journal of Cancer 2001, 37, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.B.; et al. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory. A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological assessment 1992, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.B.; et al. Predictive and treatment validity of life satisfaction and the quality of life inventory. Assessment 2005, 12, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas-Diener, R. Practicing positive psychology coaching: Assessment, activities and strategies for success. 2010: John Wiley & Sons.

- Newell, S.A; Sanson-Fisher, R.W.; Savolainen, N.J. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2002, 94, 558–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, H.; et al. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical oncology 2013, 31, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, A.M.; Johnson, J. The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology; John Wiley & Sons: 2016.

- Firkins, J.; et al. Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, A.; et al. A meta-analytic review of the relationship of cancer coping self-efficacy with distress and quality of life. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshina, N.; Falk, R.S.; Hofvind, S. S.; Hofvind, S. Long-term quality of life among breast cancer survivors eligible for screening at diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public health 2021, 199, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; et al. Dimensions of quality of life and psychosocial variables most salient to colorectal cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer 2006, 15, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).