Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

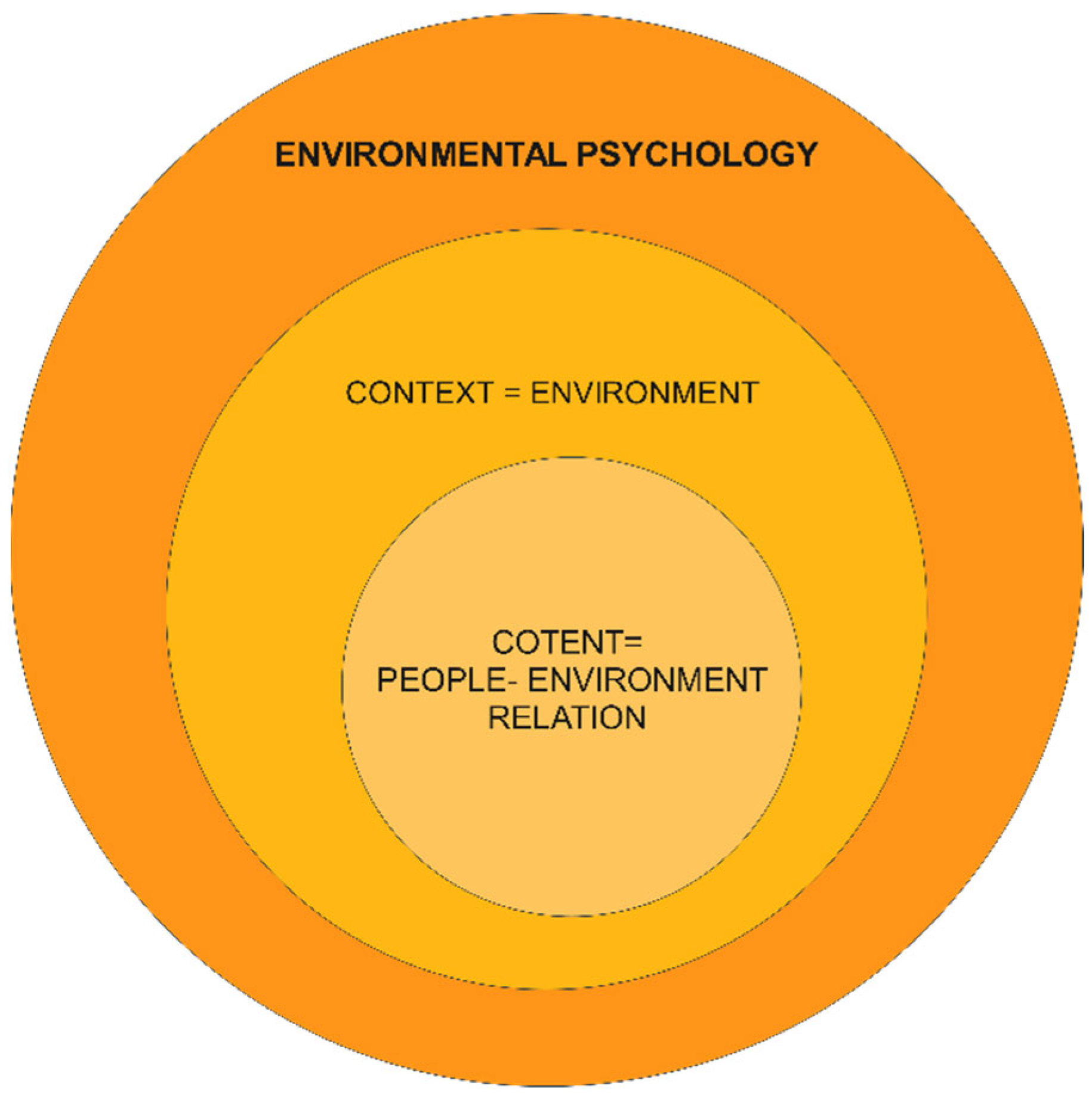

1.1. Environmental Psychology

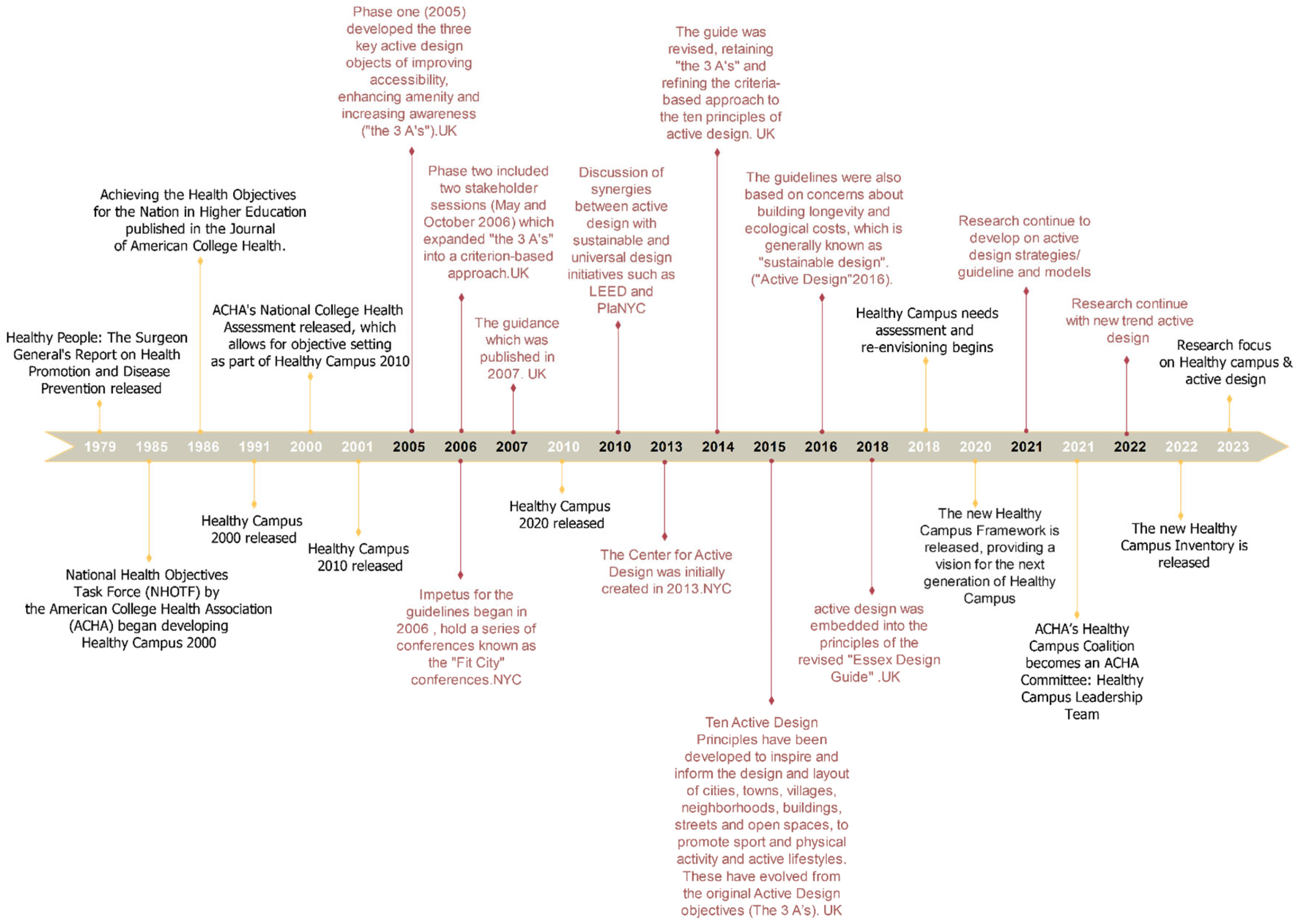

1.2. Healthy Campus as a New Trend

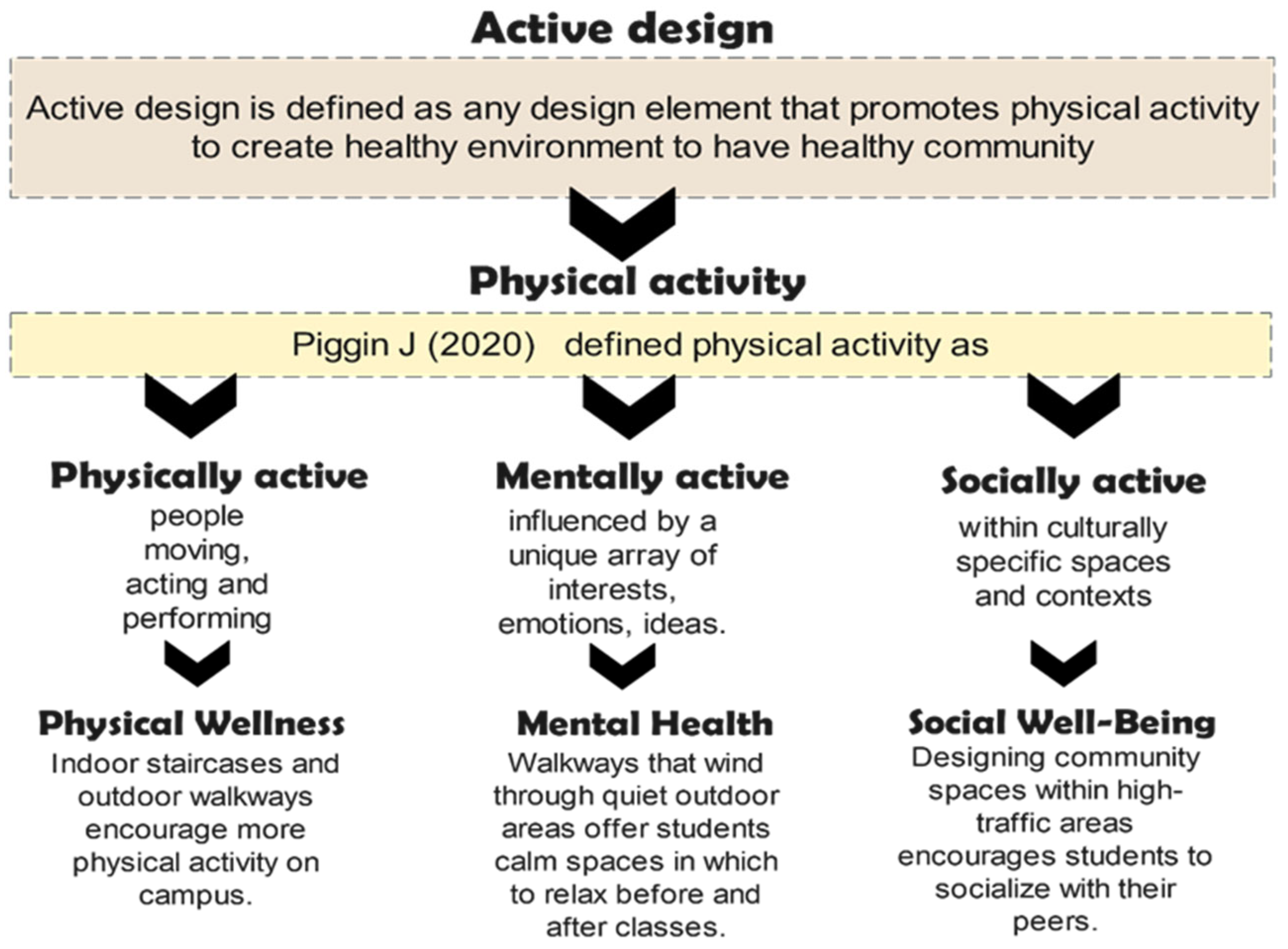

1.3. Active Design and Physical Activity

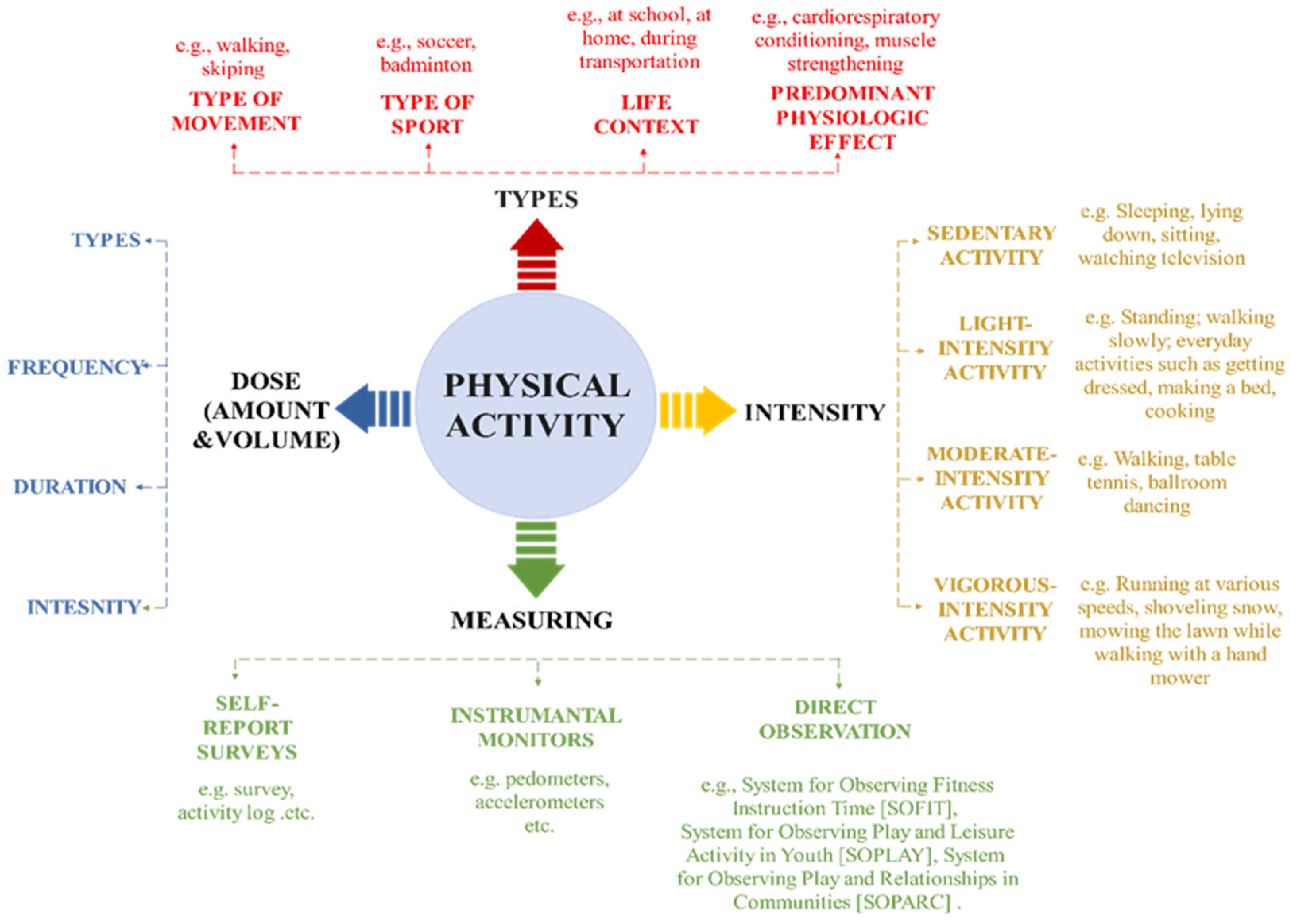

1.3.1. Classification of Physical Activity in Terms of the Active Design Approach

- Physically active: such as the person moving, acting and performing to achieve physical wellness in the built environment could be adopted as indoor staircases and outdoor walkways encourage more physical activity on campus .etc.

- Mentally active: influenced by a unique array of interests, emotions, and ideas to achieve mental health in a built environment could be adopted as walkways that wind through quiet outdoor areas offer students calm spaces in which to relax before and after classes (DeClercq, C., 2016) (WHO)

- Socially active: within culturally specific spaces and contexts to achieve social well-being in a built environment could be adopted as Designing community spaces within high-traffic areas encourages students to socialize with their peers.

1.3.2. Types of Physical Activity and its Measurement

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Survey

| Demographic Survey | Count | Table N % | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

University Campus |

Case 1 = University of Dohuk | 141 | 32.9% |

| Case 2 = University of Sulaimani | 67 | 15.7% | |

| Case 3 = University of Zakho | 29 | 6.8% | |

| Case 4 = Koya University | 28 | 6.5% | |

| Case 5 = Cihan University - Erbil | 43 | 10.0% | |

| Case 6 = University of Tishk-Erbil | 40 | 9.3% | |

| Case 7 = The Lebanese French University-Erbil | 25 | 5.8% | |

| Case 8 = Knowledge University-Erbil | 25 | 5.8% | |

| Case 9 = Nawroz University -Dohuk | 18 | 4.2% | |

| Case 10 = Catholic University -Erbil | 12 | 2.8% | |

|

Gender |

Male | 176 | 41.2% |

| Female | 251 | 58.8% | |

|

Age (Binned) |

<= 18 | 20 | 4.8% |

| 19 - 23 | 334 | 79.3% | |

| 24 - 28 | 63 | 15.0% | |

| 29 - 33 | 4 | 1.0% | |

| 34+ | 0 | 0.0% | |

|

Weight (Binned) |

<= 40 | 3 | 0.7% |

| 41 - 60 | 199 | 48.2% | |

| 61 - 80 | 151 | 36.6% | |

| 81 - 100 | 50 | 12.1% | |

| 101 - 120 | 9 | 2.2% | |

| 121 - 140 | 1 | 0.2% | |

| 141+ | 0 | 0.0% | |

|

Material status |

Single | 387 | 91.7% |

| Married | 35 | 8.3% | |

|

Living arrangement |

Home | 335 | 78.8% |

| Dormitory | 79 | 18.6% | |

| with a friend to rent a house/apartment | 11 | 2.6% | |

|

Having chronic disease |

Yes | 45 | 10.6% |

| No | 379 | 89.4% | |

|

Do sport (any kind) |

Yes | 245 | 58.2% |

| No | 176 | 41.8% | |

|

Hours of exercise per week |

<=1 | 150 | 42.0% |

| 2 | 108 | 30.3% | |

| 3 | 50 | 14.0% | |

| >=4 | 49 | 13.7% | |

|

Location (doing sport) |

Inside University Campus | 66 | 19.7% |

| Outside University Campus | 250 | 74.6% | |

| Both | 19 | 5.7% | |

|

Fixed setting (doing sport) |

Indoor (building) | 157 | 50.0% |

| Outdoor (site plan) | 138 | 43.9% | |

| Both | 19 | 6.1% |

3.2. Missing

| Case Processing Summary | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | ||||||

| Included | Excluded | Total | ||||

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Percent | |

| Physical activity (Frequency) * University campus | 364 | 85.0% | 64 | 15.0% | 428 | 100.0% |

| Physical activity (Duration) * University campus | 362 | 84.6% | 66 | 15.4% | 428 | 100.0% |

| Physical activity (Intensity) * University campus | 365 | 85.3% | 63 | 14.7% | 428 | 100.0% |

| Mentally active (Emotion) * University campus | 426 | 99.5% | 2 | 0.5% | 428 | 100.0% |

| Socially active(Frequency) * University campus | 396 | 92.5% | 32 | 7.5% | 428 | 100.0% |

| Socially active(Duration) * University campus | 392 | 91.6% | 36 | 8.4% | 428 | 100.0% |

| Socially active(Importance) * University campus | 400 | 93.5% | 28 | 6.5% | 428 | 100.0% |

3.3. Physical Activity Categories

3.3.1. Physical Activity

| Descriptives statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| Physical activity (Frequency) | Case 1 | 116 | 3.2059 | 1.88316 | 0.17485 | 2.8596 | 3.5523 | 1 | 7 |

| Case 2 | 48 | 1.8771 | 1.19052 | 0.17184 | 1.5314 | 2.2228 | 1 | 5 | |

| Case 3 | 28 | 2.5493 | 1.49646 | 0.28281 | 1.9691 | 3.1296 | 1 | 5 | |

| Case 4 | 17 | 1.4765 | 0.9763 | 0.23679 | 0.9745 | 1.9784 | 1 | 3.5 | |

| Case 5 | 42 | 2.4901 | 1.64798 | 0.25429 | 1.9765 | 3.0036 | 1 | 7 | |

| Case 6 | 39 | 1.7465 | 0.45192 | 0.07237 | 1.6 | 1.893 | 1 | 3.75 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 1.178 | 0.26657 | 0.05331 | 1.068 | 1.288 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 8 | 24 | 2.5357 | 1.10814 | 0.2262 | 2.0678 | 3.0036 | 1 | 4.75 | |

| Case 9 | 15 | 3.6756 | 1.36785 | 0.35318 | 2.9181 | 4.433 | 1.5 | 6 | |

| Case 10 | 10 | 3.4567 | 1.59831 | 0.50543 | 2.3133 | 4.6 | 1 | 7 | |

| Total | 364 | 2.5032 | 1.60788 | 0.08428 | 2.3375 | 2.669 | 1 | 7 | |

| Physical activity (Duration) | Case 1 | 115 | 1.6391 | 0.80329 | 0.07491 | 1.4907 | 1.7875 | 1 | 4 |

| Case 2 | 47 | 1.7259 | 1.29861 | 0.18942 | 1.3446 | 2.1072 | 1 | 7 | |

| Case 3 | 29 | 1.908 | 1.32667 | 0.24636 | 1.4034 | 2.4127 | 1 | 6 | |

| Case 4 | 16 | 1.3688 | 0.69447 | 0.17362 | 0.9987 | 1.7388 | 1 | 3 | |

| Case 5 | 42 | 1.7286 | 0.50822 | 0.07842 | 1.5703 | 1.887 | 1 | 3 | |

| Case 6 | 39 | 1.4774 | 0.40715 | 0.0652 | 1.3454 | 1.6094 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 1.3219 | 0.29562 | 0.05912 | 1.1999 | 1.4439 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 8 | 24 | 1.6657 | 0.77699 | 0.1586 | 1.3376 | 1.9938 | 1 | 4 | |

| Case 9 | 15 | 1.5744 | 0.56851 | 0.14679 | 1.2596 | 1.8893 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Case 10 | 10 | 1.5633 | 0.9326 | 0.29491 | 0.8962 | 2.2305 | 1 | 3.5 | |

| Total | 362 | 1.628 | 0.84941 | 0.04464 | 1.5402 | 1.7158 | 1 | 7 | |

| Physical activity (Intensity) | Case 1 | 116 | 1.9253 | 0.5733 | 0.05323 | 1.8198 | 2.0307 | 1 | 3 |

| Case 2 | 49 | 1.6095 | 0.53709 | 0.07673 | 1.4553 | 1.7638 | 1 | 3 | |

| Case 3 | 29 | 1.7836 | 0.57828 | 0.10738 | 1.5637 | 2.0036 | 1 | 3 | |

| Case 4 | 17 | 1.584 | 0.44265 | 0.10736 | 1.3564 | 1.8116 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 5 | 42 | 1.5935 | 0.479 | 0.07391 | 1.4442 | 1.7427 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Case 6 | 39 | 1.45 | 0.52432 | 0.08396 | 1.28 | 1.62 | 1 | 3 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 1.1295 | 0.20258 | 0.04052 | 1.0459 | 1.2131 | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Case 8 | 23 | 1.2479 | 0.38154 | 0.07956 | 1.0829 | 1.4129 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 9 | 15 | 1.6333 | 0.44633 | 0.11524 | 1.3862 | 1.8805 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 10 | 10 | 1.65 | 0.53547 | 0.16933 | 1.2669 | 2.0331 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Total | 365 | 1.6501 | 0.56258 | 0.02945 | 1.5921 | 1.708 | 1 | 3 | |

3.3.2. Mentally Active

| Descriptives statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| Mentally active (Emotion) | Case 1 | 140 | 4.1008 | 0.49119 | 0.04151 | 4.0187 | 4.1828 | 3 | 6.5 |

| Case 2 | 67 | 3.7299 | 0.628 | 0.07672 | 3.5768 | 3.8831 | 1 | 4.88 | |

| Case 3 | 28 | 4.0079 | 0.48574 | 0.0918 | 3.8195 | 4.1962 | 3.13 | 5 | |

| Case 4 | 28 | 3.8386 | 0.37015 | 0.06995 | 3.6951 | 3.9822 | 3.25 | 4.63 | |

| Case 5 | 43 | 3.8343 | 0.40341 | 0.06152 | 3.7102 | 3.9585 | 3 | 4.63 | |

| Case 6 | 40 | 3.8469 | 0.50676 | 0.08013 | 3.6848 | 4.0089 | 2.63 | 4.63 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 3.685 | 0.59852 | 0.1197 | 3.4379 | 3.9321 | 1.88 | 4.88 | |

| Case 8 | 25 | 3.8721 | 0.63768 | 0.12754 | 3.6089 | 4.1354 | 1.75 | 5 | |

| Case 9 | 18 | 4.0625 | 0.56107 | 0.13225 | 3.7835 | 4.3415 | 2.88 | 4.75 | |

| Case 10 | 12 | 3.9896 | 0.42459 | 0.12257 | 3.7198 | 4.2594 | 3.38 | 4.75 | |

| Total | 426 | 3.9258 | 0.53567 | 0.02595 | 3.8748 | 3.9768 | 1 | 6.5 | |

3.3.3. Socially Active

| Descriptives statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | Min | Max | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||||

| Socially active (Frequency) | Case 1 | 132 | 2.2109 | 1.11347 | 0.09692 | 2.0191 | 2.4026 | 1 | 8 |

| Case 2 | 57 | 1.7497 | 1.16049 | 0.15371 | 1.4418 | 2.0576 | 1 | 7 | |

| Case 3 | 25 | 1.9567 | 1.57253 | 0.31451 | 1.3076 | 2.6058 | 1 | 7 | |

| Case 4 | 24 | 1.8153 | 0.87774 | 0.17917 | 1.4446 | 2.1859 | 1 | 4.33 | |

| Case 5 | 40 | 1.8854 | 0.80801 | 0.12776 | 1.627 | 2.1438 | 1 | 4 | |

| Case 6 | 40 | 1.7846 | 0.38993 | 0.06165 | 1.6599 | 1.9093 | 1 | 2.67 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 1.266 | 0.33494 | 0.06699 | 1.1277 | 1.4043 | 1 | 2.25 | |

| Case 8 | 24 | 3.2569 | 0.89108 | 0.18189 | 2.8807 | 3.6332 | 1.5 | 5 | |

| Case 9 | 18 | 3.5139 | 1.3661 | 0.32199 | 2.8345 | 4.1932 | 1 | 6 | |

| Case 10 | 11 | 3.0848 | 0.98819 | 0.29795 | 2.421 | 3.7487 | 1.2 | 4.5 | |

| Total | 396 | 2.1158 | 1.14925 | 0.05775 | 2.0022 | 2.2293 | 1 | 8 | |

| Socially active (Duration) | Case 1 | 132 | 1.954 | 0.84987 | 0.07397 | 1.8077 | 2.1004 | 1 | 6.33 |

| Case 2 | 55 | 2.0909 | 1.01312 | 0.13661 | 1.817 | 2.3648 | 1 | 6 | |

| Case 3 | 24 | 2.0354 | 2.02444 | 0.41324 | 1.1806 | 2.8903 | 1 | 10 | |

| Case 4 | 23 | 1.4312 | 0.62293 | 0.12989 | 1.1618 | 1.7005 | 1 | 3.67 | |

| Case 5 | 40 | 2.1004 | 1.43208 | 0.22643 | 1.6424 | 2.5584 | 1 | 10 | |

| Case 6 | 40 | 1.5362 | 0.46975 | 0.07427 | 1.386 | 1.6865 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 1.3933 | 0.26308 | 0.05262 | 1.2847 | 1.5019 | 1 | 1.75 | |

| Case 8 | 24 | 1.7014 | 1.30516 | 0.26642 | 1.1503 | 2.2525 | 1 | 6.75 | |

| Case 9 | 18 | 1.7824 | 0.85517 | 0.20157 | 1.3571 | 2.2077 | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Case 10 | 11 | 1.8682 | 0.7744 | 0.23349 | 1.3479 | 2.3884 | 1 | 3.5 | |

| Total | 392 | 1.8583 | 1.03942 | 0.0525 | 1.7551 | 1.9615 | 1 | 10 | |

| Socially active (Importance) | Case 1 | 132 | 1.7068 | 0.44653 | 0.03887 | 1.6299 | 1.7837 | 1 | 3 |

| Case 2 | 60 | 1.7869 | 0.43991 | 0.05679 | 1.6733 | 1.9006 | 1 | 2.67 | |

| Case 3 | 27 | 1.6407 | 0.42848 | 0.08246 | 1.4712 | 1.8102 | 1 | 2.33 | |

| Case 4 | 23 | 1.5022 | 0.48654 | 0.10145 | 1.2918 | 1.7126 | 1 | 2.33 | |

| Case 5 | 40 | 1.6767 | 0.43963 | 0.06951 | 1.5361 | 1.8173 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Case 6 | 40 | 1.4254 | 0.40236 | 0.06362 | 1.2967 | 1.5541 | 1 | 2.33 | |

| Case 7 | 25 | 1.322 | 0.37527 | 0.07505 | 1.1671 | 1.4769 | 1 | 2.33 | |

| Case 8 | 24 | 1.4757 | 0.4541 | 0.09269 | 1.2839 | 1.6674 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 9 | 18 | 1.588 | 0.40672 | 0.09586 | 1.3857 | 1.7902 | 1 | 2 | |

| Case 10 | 11 | 1.7636 | 0.28302 | 0.08533 | 1.5735 | 1.9538 | 1.33 | 2.2 | |

| Total | 400 | 1.6298 | 0.44966 | 0.02248 | 1.5856 | 1.6739 | 1 | 3 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

|

Physical activity (Frequency) |

Between Groups | 190.059 | 9 | 21.118 | 9.989 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 748.397 | 354 | 2.114 | |||

| Total | 938.455 | 363 | ||||

|

Physical activity (Duration) |

Between Groups | 7.585 | 9 | .843 | 1.173 | .311 |

| Within Groups | 252.876 | 352 | .718 | |||

| Total | 260.461 | 361 | ||||

|

Physical activity (Intensity) |

Between Groups | 21.652 | 9 | 2.406 | 9.129 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 93.553 | 355 | .264 | |||

| Total | 115.205 | 364 | ||||

|

Mentally active (Emotion) |

Between Groups | 9.773 | 9 | 1.086 | 4.027 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 112.177 | 416 | .270 | |||

| Total | 121.951 | 425 | ||||

| Socially active (Frequency) | Between Groups | 112.964 | 9 | 12.552 | 11.853 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 408.739 | 386 | 1.059 | |||

| Total | 521.704 | 395 | ||||

| Socially active (Duration) | Between Groups | 21.729 | 9 | 2.414 | 2.302 | .016 |

| Within Groups | 400.703 | 382 | 1.049 | |||

| Total | 422.432 | 391 | ||||

| Socially active (Importance) | Between Groups | 7.568 | 9 | .841 | 4.486 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 73.107 | 390 | .187 | |||

| Total | 80.675 | 399 | ||||

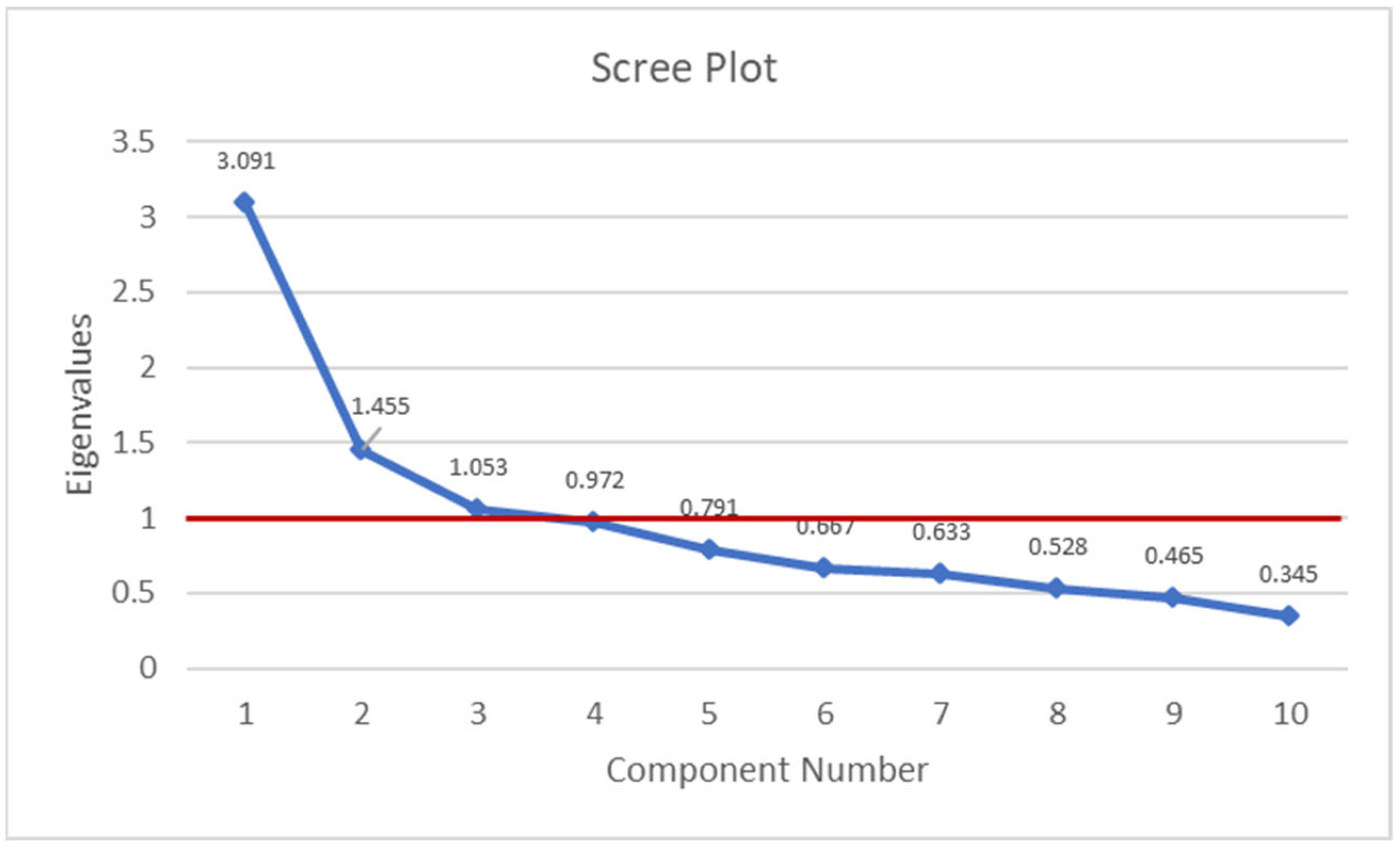

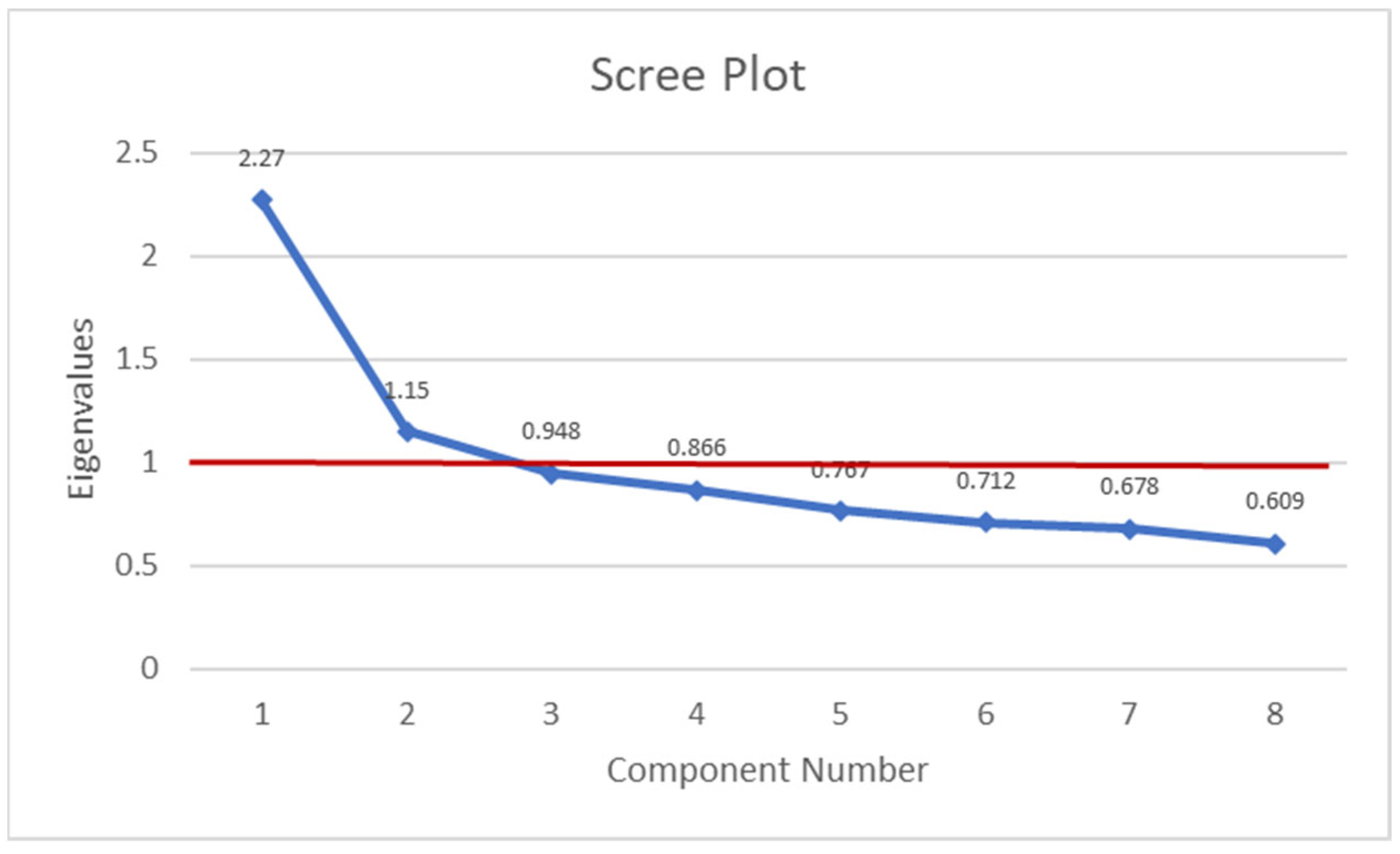

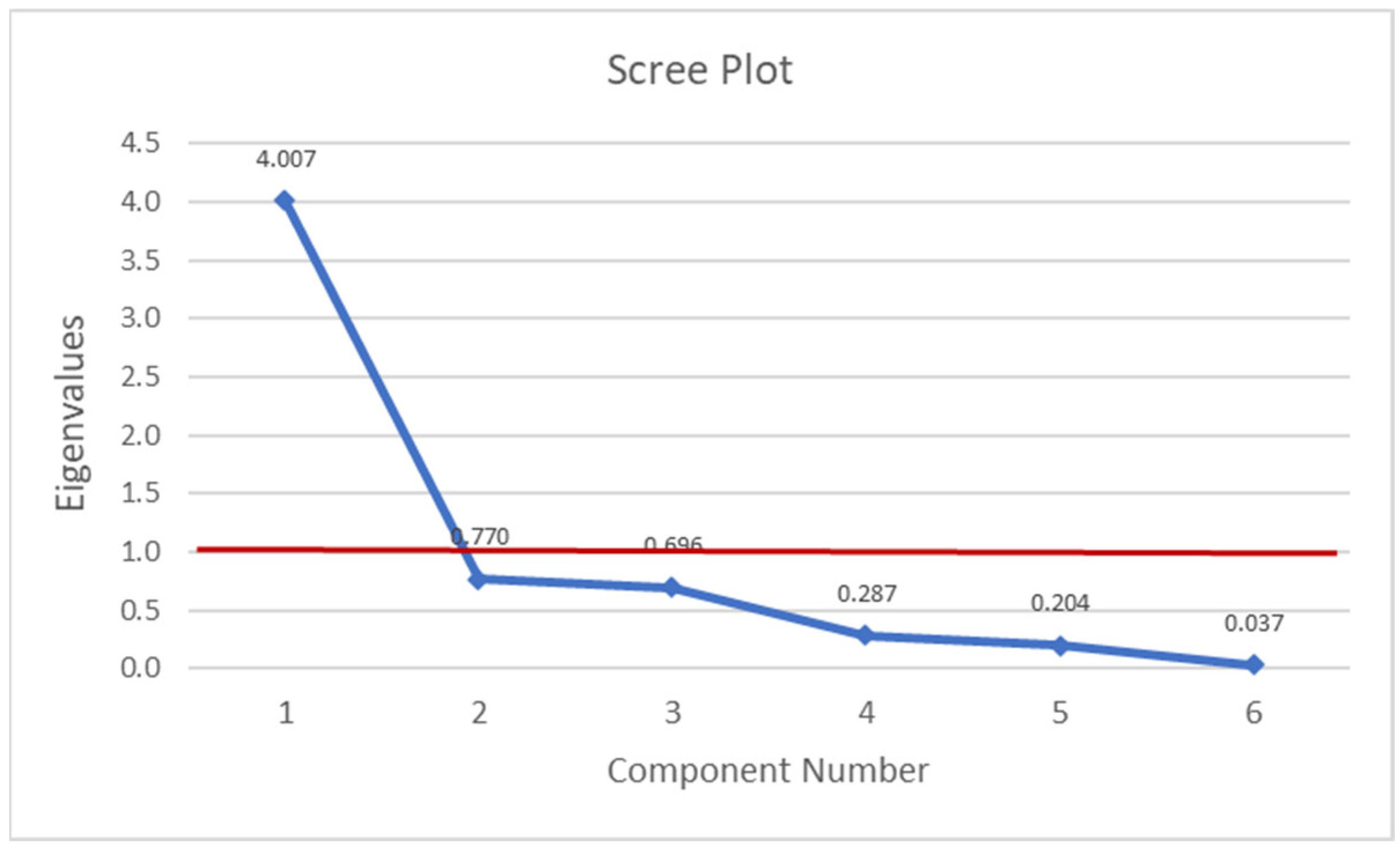

3.3.4. Factor Analyses for Physical Activity, Mentally Active and Socially Active

- Physical activity extraction:

| Rotated Component Matrixa | Rotated Component Matrixa | Factor Matrixa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physically active | Component | Mentally active | Component | Socially active | Factor | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Swimming | 0.8 | I feel anxiety every 4 weeks. | 0.676 | Leisure time (cafeteria, restaurant) | 0.484 | |||||

| Tennis | 0.747 | I feel depressed when I am not active | 0.622 | Public spaces (green area, park, benches) | 0.714 | |||||

| Basketball | 0.663 | I feel safer when I am doing physical activities. | 0.602 | Library | 0.753 | |||||

| Working performance (university activity participants) | 0.611 | Emotionally I feel good when I am physically active | 0.509 | Event-Hall spaces | 0.959 | |||||

| Exercise physiology (aerobic, yoga) | 0.539 | I feel comfortable everyday walking | 0.454 | Theatre | 0.943 | |||||

| Football | 0.517 | I expend energy on daily activities. | 0.792 | Shopping- market- kiosk | 0.761 | |||||

| Walking | 0.78 | I feel good about my Skeletal muscles and health | 0.611 | Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | ||||||

| Running | 0.734 | My mood motivates me to move. | 0.567 | a. 1 factor extracted. 5 iterations required. | ||||||

| Fitness/gym | 0.693 | Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | Only one factor was extracted. The solution cannot be rotated. | |||||||

| 8-Bicycling | 0.8 | Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. a | ||||||||

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | a. Rotation converged in 3 iterations. | |||||||||

| Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. a | ||||||||||

| a. Rotation converged in 5 iterations. | ||||||||||

- 2.

- Mentally active extraction

- 3.

- Socially active extraction

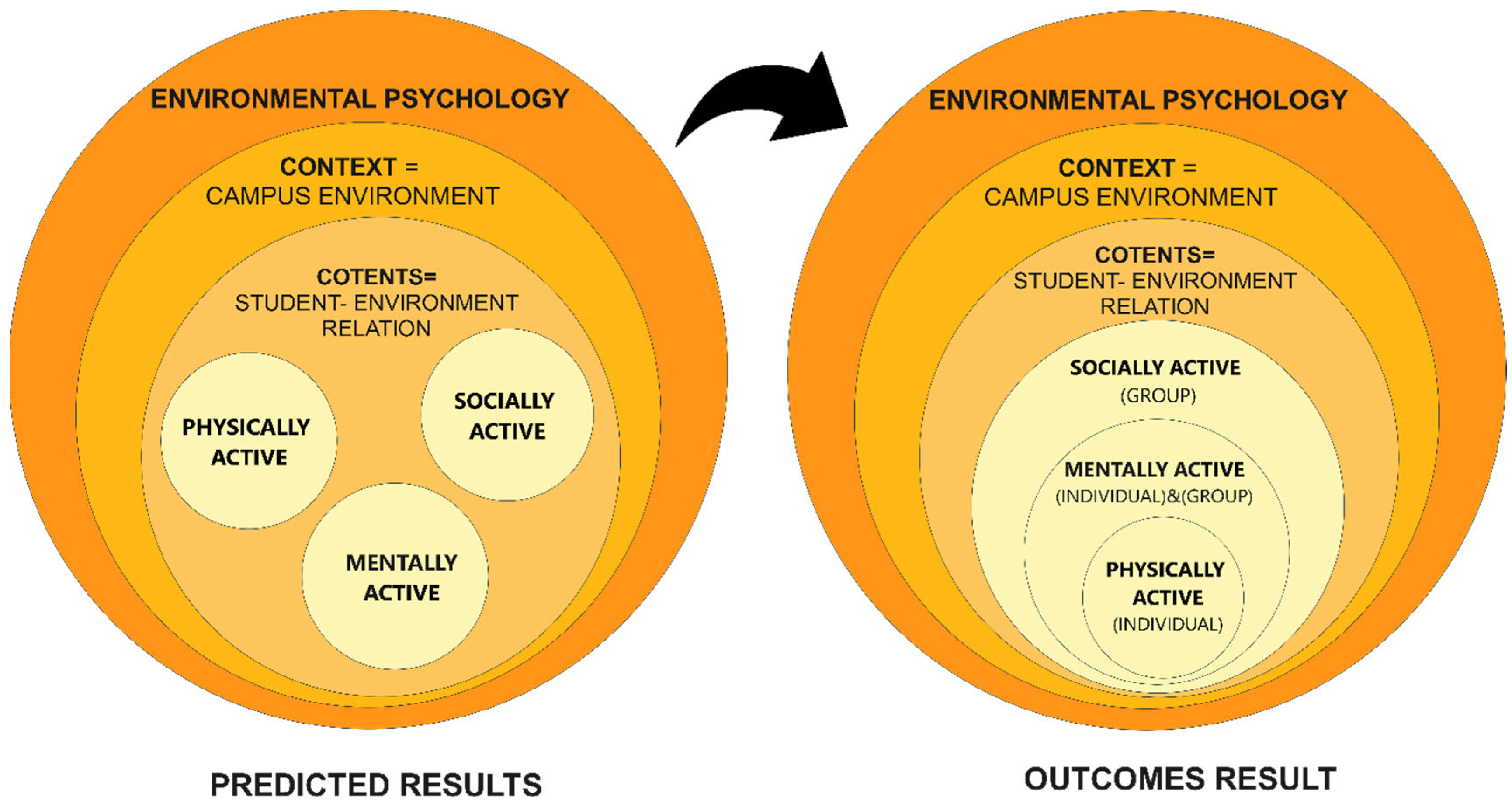

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- It concluded that only 19.7 % do physical activity at university campus .this indicate that students are not physically active at university campus the reason behind it they do not have time to do so. They are more physically active out on campus. Another reason all physical activities are not provided for students from university campuses. And 74.6% are physically active outside campus the reason to shape their body become attractive more than mentally be active only 5.7% of students do sport both inside and outside of campus this rate is for males who use the football stadium at the university campus.

- The new trends of active design emphasise creating active behaviour in the built environment starting from the individual, therefore society becomes active and would have mental well-being individually. But this study discovered that students are more interested in socially being active and they spend their break time with their friends at social locations on campus emotionally they are more satisfied than physical activity used to shape their bodies. This indicates that by creating new social activities inside the campus-built environment rapidly and positively students achieve mental well-being. Thus The environmental psychology of the campus could be considered as social-well being of users either students or staff the context is the environment of students that includes activity that affects the social well-being of students. In open-ended questions the student claimed to have more time to join social activities therefore university should think about it how they can make them socially active during university time which has a direct effect on the mental health of the university.

- The theory to achieve healthy behaviour for an active approach is different from the theory used for environmental psychology such as phenomenology, ontology..etc. A future study should be done to accumulate all environmental psychology theories to create a foundation for inventing new social activities for university campuses.

- Several researchers introduced their work in environmental psychology which differs from healthy behaviour theory in that something effect indirectly on human psychology and behaviour through experiencing in context but in healthy behaviour theory the activity could be created in a built environment and encourage them to do so.

- The context and content of environmental simulation are essential components of EP social psychology. Therefore, the environment is now the basis of context in EP, but other disciplines regard the social context as context when describing people-environment interactions.

- Future research should incorporate context-based theory since it will enhance EP’s fundamental concepts. EP should be just as willing to consider context as core which is after all the way offer subjects treat psychology (as one of their contexts). Thus EP is still a subject with a variety of physical world paradigms physical world. In addition, where do the boundaries of EPS content and context lie? What content and context? Local and global real world in which people live that EP and other areas of psychology should extend their focus of attention from individual psychological processes to their social, physical and temporal context.

- Another future research that could focus on EP could be set through perception & cognition the theory adopted for it is phenomenology ontology healthy behaviour, healthy in context increase social-wellbeing for EP.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- "Fit-City 2: Promoting Physical Activity through Design"(PDF). American Institute of Architects New York Chapter. 2007. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161213211217/http://aiany.aiany.org/corecode/uploads/document/uploaded_pdfs/corecode_aianyaia/FitCity2_Publication_Final_163.pdf.

- Ahmed, R.M., Abdullah, M.O. and Altun, Y., 2022. Comparison Between Factor Analysis and Cluster Analysis to Determine the Most Important Affecting Factors for Students’ Admission and Their Interests in The Specializations: A Sample of Salahaddin University-Erbil. Zanco Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences, 34(s6), pp.12-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21271/ZJPAS.34.s6.3. [CrossRef]

- American College Health Association. (2023). The healthy campus framework. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association. https://www.acha.org/HealthyCampus/HealthyCampus/Framework.aspx accessed 4 May of 2023.

- American College Health Association. 2015a. Healthy Campus 2020: About. Retrieved December 15, 2015, from the World Wide Web: www.acha.org/HealthyCampus/About/HealthyCampus/About. aspx?hkey=2c0c96b6-c330-47e1-87fe-747ec8397e85.

- Azeez, S.A.; Mustafa, F.A.; Ahmed, R.M. A Meta-Analysis of Evidence Synthesis for a Healthy Campus Built Environment by Adopting Active Design Approaches to Promote Physical Activity. Buildings 2023, 13, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13051224. [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg, M. R., Burney, D., Farley, T., Sadik-Khan, J., & Burden, A. (2010). Active design guidelines: promoting physical activity and health in design. The City of New York.: Report from City Council. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/environmental/active-design-guidelines.pdf.

- T., Yan, Z. and Heene, M., 2020. Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. Routledge.

- Bustler FitCity 10: Promoting Physical Activity through Design 2015. Available online: https://bustler.net/events/latest/6401/fitcity-10-promoting-physical-activity-through-design (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Castro, O., Bennie, J., Vergeer, I. et al. How Sedentary Are University Students? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev Sci 21, 332–343 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01093-8. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.P. (2006) American places: In search of the twenty-first-century campus. Westport: Greenwood.

- Charehjoo, F., Etesam, I. and Rasoulpour, H., 2018. The Role of environmental psychology in Architecture and urban design. Scientific Journal “Academia Architecture and Construction, 1(2), pp.11-15.

- Chen, W., M. Zaid, S., & Nazarali, N. (2016). Environmental psychology: the urban built environment impact on human mental health. Planning Malaysia, 14(5). https://doi.org/10.21837/pm.v14i5.190. [CrossRef]

- Coulson, J., Roberts, P., and Taylor, I. (2010) University planning and architecture: The search for perfection. Westport: Routledge.

- Coulson, J., Roberts, P., and Taylor, I. (2014) University trends: Contemporary campus design. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Craik, K.H., 1973. Environmental psychology. Annual review of psychology, 24(1), pp.403-422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.24.020173.002155. [CrossRef]

- Danaei, G.; Ding, E.L.; Mozaffarian, D.; Taylor, B.; Rehm, J.; Murray, C.J.L.; Ezzati, M. The Preventable Causes of Death in the United States: Comparative Risk Assessment of Dietary, Life. style, and Metabolic Risk Factors. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000058.

- De Groot, J.I., 2019. Environmental psychology: An introduction.

- DeClercq, Caitlin. "Toward the healthy campus: methods for evidence-based planning and design." Planning for Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 3, Apr.-June 2016, pp. 86+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A471145041/AONE?u=anon~d3d2aea2&sid=googleScholar&xid=ebb6fe81. Accessed 24 May 2023.

- DeJonge, M.L., Jain, S., Faulkner, G.E. and Sabiston, C.M., 2021. On campus physical activity programming for post-secondary student mental health: examining effectiveness and acceptability. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 20, p.100391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2021.100391. [CrossRef]

- Dober, R. P. 1996. Campus Planning. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for College and University Planning.

- Feng, H., Yang, F. Does environmental psychology matter: role of green finance and government spending for sustainable development. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30, 39946–39960 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-24969-4. [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, K. and Carr, D. eds., 2021. Handbook of ageing and the social sciences. Academic Press.

- Gebel, K.; King, L.; Bauman, A.; Vita, P.; Gill, T.; Rigby, A.; Capon, A. Creating Healthy Environments—A Review of Links between the Physical Environment, Physical Activity and Obesity; The University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2005.

- Gifford, R. (2014). Environmental psychology matters. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 541-579. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115048. [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, P.J., Remer, L.G., LaScala, E.A., 2014. Testing a social-ecological model of alcohol use: the California 50-city study. Addiction 109 (5), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12438. [CrossRef]

- Hajrasouliha, A., 2017. Campus score: Measuring university campus qualities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 158, pp.166-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.007Get rights and content. [CrossRef]

- Hajrasouliha, A.H. Master-planning the American campus: goals, actions, and design strategies. Urban Des Int 22, 363–381 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-017-0044-x. [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, S., Sabouri, S., & Ewing, R. (2020). Does density aggravate the COVID-19 pandemic? Early findings and lessons for planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(4), 495-509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1777891. [CrossRef]

- Jonathan d. Sime, what is environmental psychology? Texts, content and context, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume 19, Issue 2,1999, Pages 191-206, ISSN 0272-4944,https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0137.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494499901378). [CrossRef]

- Kenney, D.R., Dumont, R., and Kenney, G.S. (2005) Mission and place: Strengthening learning and community through campus design. Westport: Greenwood.

- LaBelle, B. Positive Outcomes of a Social-Emotional Learning Program to Promote Student Resiliency and Address Mental Health. Contemp School Psychol 27, 1–7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00263-y. [CrossRef]

- Lacasse, M.; Nienaber, S. Get Active: Implement Active Design in Your Neighborhoods and Open Spaces; The American Society of Landscape Architects: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar].

- Lam, T.M.; Vaartjes, I.; Grobbee, D.E.; Karssenberg, D.; Lakerveld, J. Associations between the Built Environment and Obesity: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2021, 20, 7.

- Lee, K. K. (2012). Developing and implementing the active design guidelines in New York City. Health & Place, 18(1), 5-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.009. [CrossRef]

- Michael R. B., David B., Thomas F., Janette S.& Amanda B. (2010) .Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health Design. New York City. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/environmental/active-design-guidelines.pdf.

- Mir IA, Ng SK, Mohd Jamali MNZ, Jabbar MA, Humayra S (2023) Determinants and predictors of mental health during and after COVID-19 lockdown among university students in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 18(1): e0280562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280562. [CrossRef]

- Mirilia Bonnes and Gianfranco Secchiaroli.Environmental Psychology: A Psycho-social Introduction. London: Sage Publications, 1995. ISBN 0 8039 7905 3. ISBN 0 8039 7906 1 (Translated from Italian, Psicologia Ambientale, 1992, by Claire Montagna).

- Mitchell, W.J., and Vest, C.M. (2007) Imagining MIT: Designing a campus for the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Nesma Sherif Samir Elrafie, Ghada Farouk Hassan, Mohamed A. El Fayoumi, Ayat Ismail, Investigating the perceived psychological stress in relevance to urban spaces’ different perceived personalities, Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Volume 14, Issue 6,2023,102116, ISSN 2090-4479, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102116.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2090447923000059). [CrossRef]

- Nurliyana Jekria, Salina Daud, Environmental Concern and Recycling Behaviour, Procedia Economics and Finance,Volume 35,2016, Pages 667-673, ISSN 2212-5671,https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00082-4.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567116000824). [CrossRef]

- Osmond, H. (1957). Function as the basis of psychiatric ward design. Psychiatric Services, 8(4), 23-30. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.8.4.23. [CrossRef]

- Paul A. Bell, Thomas C. Greene, Je¡rey D. Fisher and Andrew Baum,1996.Environmental Psychology (4th ed). By. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace. ISBN 0 15 501496-X, , 9780155014961Length 645 pages.

- Pelgrims, I., Devleesschauwer, B., Guyot, M. et al. Association between urban environment and mental health in Brussels, Belgium. BMC Public Health 21, 635 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10557-7. [CrossRef]

- Pinter-Wollman N, Jelić A, Wells NM. The impact of the built environment on health behaviours and disease transmission in social systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018 Aug 19;373(1753):20170245. doi 10.1098/rstb.2017.0245. PMID: 29967306; PMCID: PMC6030577. [CrossRef]

- Pronello, C.; Gaborieau, J.-B. Engaging in Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour Research from a Psycho-Social Perspective: A Review of Behavioural Variables and Theories. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072412. [CrossRef]

- Public Health England (2015) Active Design: Planning for health and wellbeing through sport and physical activityActive Design checklist. Sport England. https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/active-design-checklist-oct-2015.pdf?VersionId=az73PYXRmKYaXMfLu8BCxgXSByeiAQ1.

- Robbins, J.L. A New Design Movement that Can Help Us Beat Obesity. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/1663272/a-new-design-movement-that-can-help-us-beat-obesity (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Robert Bechtel; Environment & Behavior: An Introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1997. ISBN 0 8039 5795 5.

- Robert Gi¡ord. Boston: Allyn and Bacon (1997).Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practice (2nd ed). ISBN 0 205 18941 5.

- Rodríguez-Romo, G.; Acebes-Sánchez, J.; García-Merino, S.; Garrido-Muñoz, M.; Blanco-García, C.; Diez-Vega, I. Physical Activity and Mental Health in Undergraduate Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010195. [CrossRef]

- Russell Veitch and Daniel Arkkelin (1995).Environmental Psychology: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. ISBN 0 13 739954 5.

- Sallis, J.F.; Linton, L.S.; Kraft, M.K. The First Active Living Research Conference: Growth of a Transdisciplinary Field. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28 (Suppl. 2), 93–95.

- Salonee Jambusaria, Sara Berry, Shivam Bhadra, Shrutika Sanghvi (2020). Research paper on physical activity and fitness patterns among university students in Mumbai. International Journal of Advance Research, Ideas and Innovations in Technology, 6(3) www.IJARIIT.com.

- Shahadan, S.Z., Bolhan, N.S. and Ismail, M.F.M., The Association between Physical Activity Status and Mental Wellbeing among Overweight and Obese Female University Students. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences (2022) 18(19) 80-86. doi:10.47836/mjmhs.18.s19.13. [CrossRef]

- Silver, L.; Bell, F. FAIA Fit-City 2: Promoting Physical Activity through Design. Available online: https://www.aiany.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/FitCity2_Publication_Final_163.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Sport England. Active Design Checklist; Sport England: Loughborough, UK, 2015.

- Sport England. Active Design The Role of Master Planning|Phase 1; Sport England: Loughborough, UK, 2005; p. 68.

- Sport England. Jennie Price Active Design: Planning for Health and Wellbeing through Sport and Physical Activity. Public Health Engl. 2015, 2–64. Available online: https://www.rossendale.gov.uk/downloads/file/15002/active_design_planning_for_health_and_wellbeing_through_sport_and_physical_activity_sport_england_2015 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Steinmetz, C.A. (2009) Universities as a place: An intergenerational perspective on the experience of Australian university students (Doctoral dissertation, University of New South Wales Sydney, Australia 2009).

- Stevens, N. J., Tavares, S. G., & Salmon, P. M. (2021). The adaptive capacity of public space under COVID-19: Exploring urban design interventions through a sociotechnical systems approach. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 31(4), 333-348. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20906. [CrossRef]

- Strange, C.C., and Banning, J.H. (2001) Education by design: Creating campus learning environments that work. The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Tam, K.P. and Milfont, T.L., 2020. Towards cross-cultural environmental psychology: A state-of-the-art review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 71, p.101474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101474. [CrossRef]

- Tony Cassidy (1997).Environmental Psychology: Behaviour and Experience in Context. Hove, East Sussex, U.K.: Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis).ISBN 0 86377.

- Tootell, R. B., Zapetis, S. L., Babadi, B., Nasiriavanaki, Z., Hughes, D. E., Mueser, K., … & Holt, D. J. (2021). Psychological and physiological evidence for an initial ‘Rough Sketch’calculation of personal space. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-021-99578-1. [CrossRef]

- Veitch, Russell. Environmental psychology: an interdisciplinary perspective;1995; Environmental psychologyPublisher;Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice Hall Collection; urn:OCLC:record:1244737389urn:lcp:environmentalpsy0000veit:lcpdf:06fbd702-b8f6-49b3-8681-46ba1f6b73c8urn:lcp:environmentalpsy0000veit:epub:174436d4-37db-4028-8bc8-52d8272db1fd.

- Von Sommoggy J, Rueter J, Curbach J, Helten J, Tittlbach S and Loss J (2020) How Does the Campus Environment Influence Everyday Physical Activity? A Photovoice Study Among Students of Two German Universities. Front. Public Health 8:561175. doi ;10.3389/.2020.561175. [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.-Y.C.; Fung, H.-W.; Yuan, G.F. The Association between Physical Activity, Self-Compassion, and Mental Well-Being after COVID-19: In the Exercise and Self-Esteem Model Revised with Self-Compassion (EXSEM-SC) Perspective. Healthcare 2023, 11, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020233. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Van Gerven, P.W.M.; de Groot, R.H.M.; O. Eijnde, B.; Seghers, J.; Winkens, B.; Savelberg, H.H.C.M. The Association between Academic Schedule and Physical Activity Behaviors in University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021572. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Li, W. S., & Cheng, B. (2021). Study on Campus Planning from the Perspective of Environmental Behavior. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 9, 326-333. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2021.98022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., He, Z., Qian, J., Qi, X., & Tong, J. (2023). Relationship Between Mindfulness and Physical Activity in College Students: The Mediating Effect of Eudaimonic Well-Being. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 130(2), 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/00315125221149833. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).