1. Introduction

Intertemporal decision-making refers to the process by which individuals weigh and make choices regarding the value of monetary reward outcomes that occur at different times [

1]. The core content of this process is delay discounting; that is, when individuals make choices regarding the psychological trade-offs between costs and benefits that occur at different time points, they tend to give less weight to the costs and benefits of future time nodes [

2]. Researchers often use the delay discounting task to examine intertemporal decision-making [

3]. This task asks participants to choose between two rewards: a smaller reward that is immediately available (Smaller-Sooner, SS) and a larger but more distant reward, i.e., a delayed reward (Larger-Later, LL). As the acquisition time is delayed, the individual’s evaluation of the same gain or loss decreases, resulting in an increase in the discounting rate [

4].

1.1. State Anxiety, Trait Anxiety and Intertemporal Decision-making

Emotions are one of the factors affecting individuals' intertemporal decision-making [

5]. The temporal relationship between emotions and decision-making is divided into pre-decision emotion, in-decision emotion and post-decision emotion. Pre-decision emotion refers to the individual’s emotions prior to engaging in the decision-making task, which is not induced by the task but accompanies the entire decision-making process. In-decision emotion refers to the emotional experience stimulated by the decision-making process. Post-decision emotion is a pervasive and persistent emotional process that results from the decision [

6]. Most studies have examined the impact of pre-decision emotion on intertemporal decision-making. Different pre-decision emotions have different effects on intertemporal decision-making. Positive emotions (such as gratitude and happiness) and certain negative emotions (such as anger) cause individuals to prefer LL [

2,

7]. Other negative emotions (such as sadness) cause individuals to focus more on SS [

8].

The motivational dimensional model of affect posits that highly motivational negative emotions such as anxiety help individuals evaluate and escape from dangerous situations [

9]. During this process, the range of individual attention is narrowed, cognitive resources are focused on target stimuli, and cognitive flexibility is reduced [

10]. Therefore, anxiety causes individuals to focus more on immediate gains and losses and to prefer immediate gains. However, few studies have investigated the effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making, and the results of the studies that have been conducted regarding this topic are contradictory. Hanies et al (2020) and Patt et al (2021) used the same monetary delay discounting task to conduct relevant studies [

11,

12]. The former group of authors found that anxiety significantly increased the rate of individuals choosing SS, while the latter reported that anxiety was not significantly associated with the discounting rate. Based on the existing evidence, the failure to consider the influence of trait anxiety may be a key reason for the divergence of these research results. Trait anxiety is not only positively correlated with state anxiety but also affects intertemporal decision-making [

13]. Studies have reported that individuals with high trait anxiety are more likely to choose SS due to their impulsive decision-making [

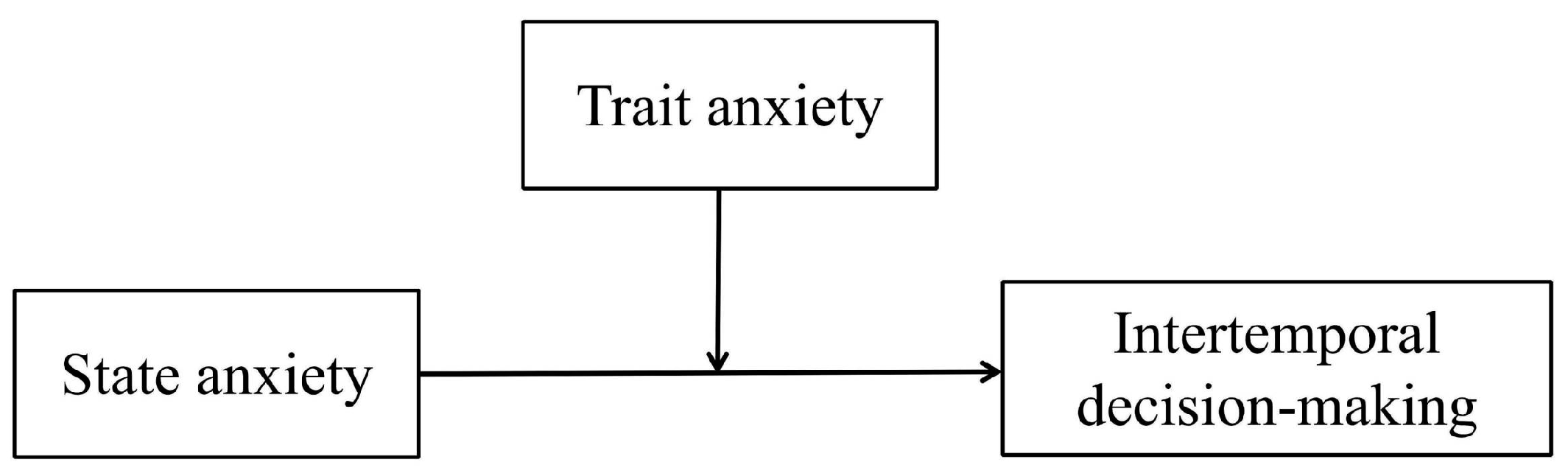

14]. Moreover, Zhao et al (2015) have also found that the higher individuals’ trait anxiety is, the weaker the positive predictive power of state anxiety on SS selection, which may even shift to a negative prediction [

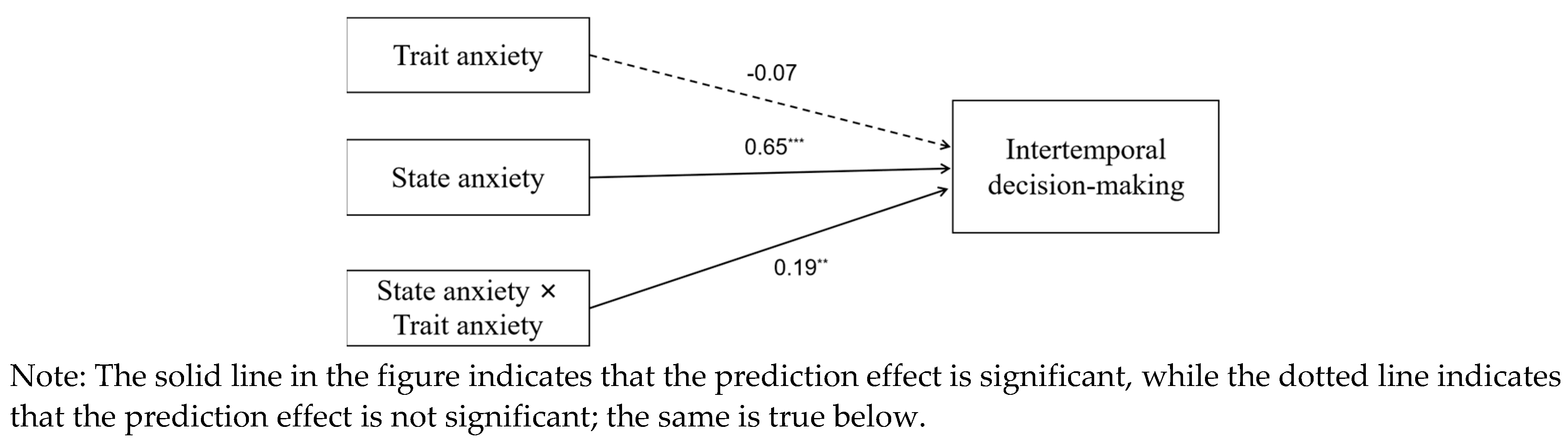

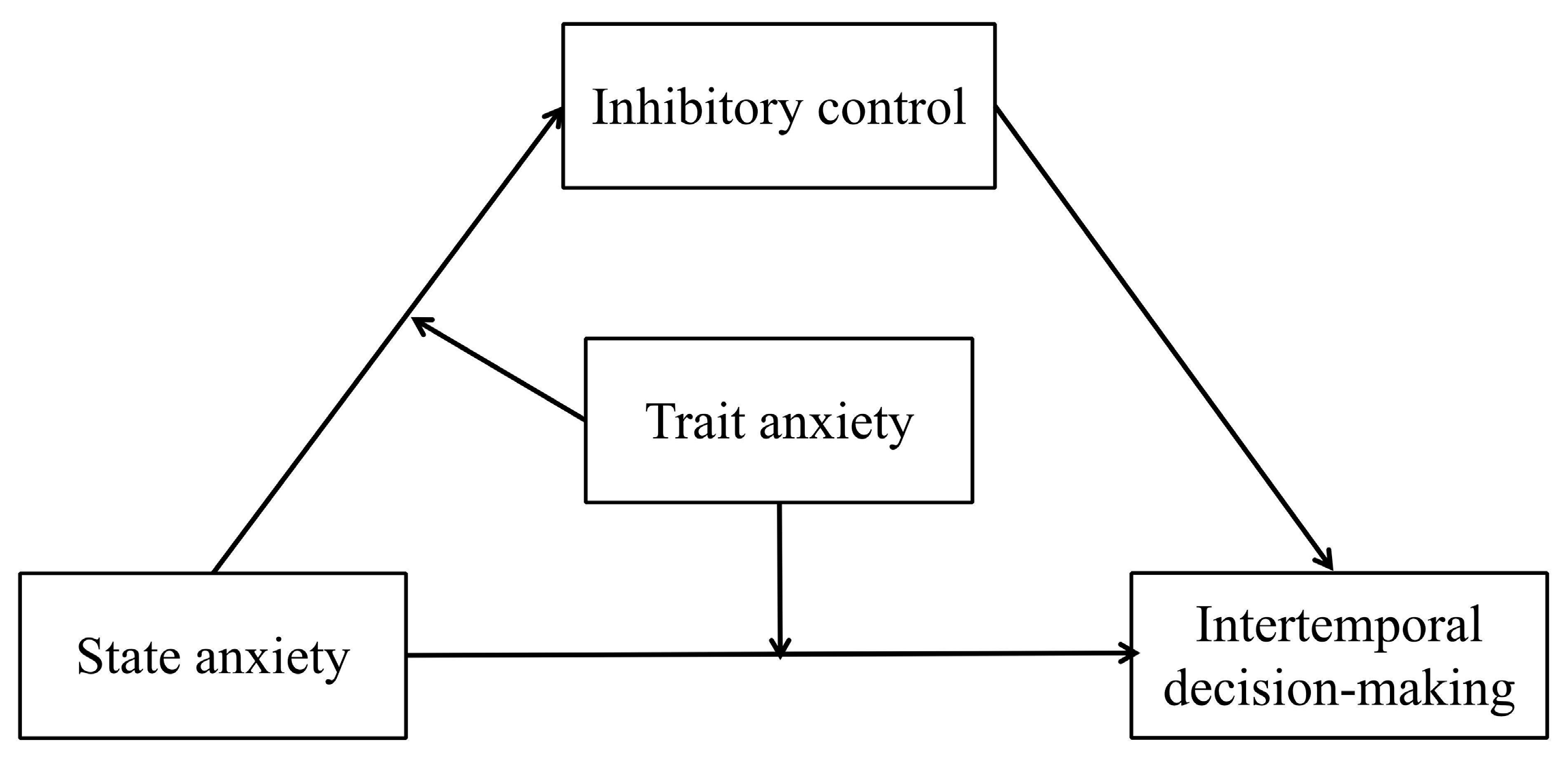

15]. However, Zhao’s study did not fully induce the anxiety of the participants and only considered the participants’ choice of SS as the dependent variable. These methods may affect the reliability of the results. Therefore, the role of trait anxiety in the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making must be verified in further detail. In summary, this study proposes Hypothesis 1: Trait anxiety moderates the effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making. The higher the individual’s trait anxiety, in cases of state anxiety, the individual is more inclined to make impulsive intertemporal decisions, that is, to choose smaller short-term gains (as shown in

Figure 1).

1.2. State Anxiety, Trait Anxiety, Inhibitory Control, and Intertemporal Decision-making

Processing negative emotion needs a large amount of cognitive resources and self-control capacity, resulting in more irrational behaviors [

16], such as irrational intertemporal decision-making. Inhibitory control, as an executive function [

17], refers to the ability to inhibit interfering, irrelevant behaviours or impulsive behaviours [

18]. Adolescents’ inhibitory control improves, and their discounting rate for monetary rewards decreases [

19]. Hong (2014) believe the lottery gamblers’ higher rate of discounting is attributed to their low inhibitory control [

20]. Therefore, inhibitory control may be an important factor influencing intertemporal decision-making.

Regarding the relationship between anxiety and inhibitory control, previous studies have recognized the fact that the cognitive ability decline caused by anxiety could lead to impaired inhibitory control; however, there are differences in the anxiety components that have been reported to play a role in this process. Some researchers have claimed that cognitive impairment is present only in high trait anxiety groups, resulting in deficits in inhibitory control from functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging(fMRI), Event-related Potential(ERP) and Behaviour studies [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Other scholars, in contrast, have reported that cognitive impairment is caused by transiently elevated state anxiety, thereby reflecting the temporary depletion of cognitive ability caused by anxiety states [

25], which in turn impairs inhibitory control [

26]. In addition, few previous studies have considered the role of both state anxiety and trait anxiety in this process. Myles examined the effects of state anxiety and trait anxiety on inhibitory control simultaneously and found that the effects of state anxiety on inhibitory control differed significantly only in individuals with high trait anxiety [

13]. These viewpoints and results must be tested empirically in further detail.

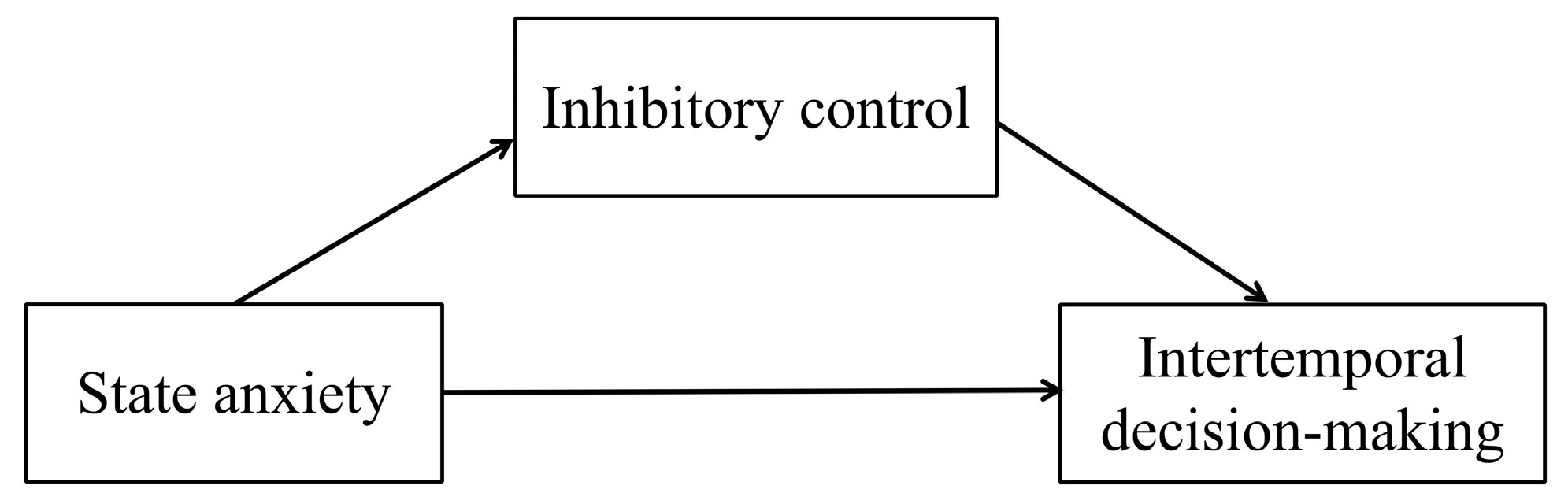

Based on previous studies, trait anxiety may moderate the effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making. Trait anxiety may also be a moderating variable associated with the effect of state anxiety on inhibitory control and a boundary condition on this effect in the context of intertemporal decision-making. Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis 2: Inhibitory control mediates the predictive effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making (as shown in

Figure 2). Individuals with higher state anxiety exhibit weaker inhibitory control ability and thus make more impulsive intertemporal decisions. And the study also proposes Hypothesis 3: The mediating process by which state anxiety affects intertemporal decision-making via inhibitory control is mediated by trait anxiety (as shown in

Figure 3). Individuals with higher trait anxiety have weaker inhibitory control ability when they have higher state anxiety, and they thus make more impulsive intertemporal decisions.

2. Study 1: The Role of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-making: A Moderation Model of Trait Anxiety

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

Based on the power analysis by G*Power program(effect size f2 = 0.20, power = 0.80, α = 0.05), the minimum sample size required is 70. A total of 173 college students in Zhejiang University of Technology were recruited via their campus bulletin board in January 2022, including 106 females, with an average age of 19.30 years old (SD = 1.76). This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University of Technology in Hangzhou, China (ethics approval number: zjut202104735001-1). All the participants signed informed consent forms prior to participating in the study.

2.1.2. Materials and Procedures

The Chinese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [

27] was used to measure the trait anxiety and state anxiety of participants. The inventory consists of 40 items. The first 20 items are associated with the State Anxiety Inventory, which requires the participants to evaluate how they feel at the moment they complete the inventory. The remaining 20 items are associated with the Trait Anxiety Inventory. The participants are asked to evaluate their situation over the past week. The inventory is scored on a 4-point scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. The inventory has been widely used to measure the anxiety of Chinese college students [

28,

29,

30]. The split-half reliability of the inventory in this study was 0.94, and the consistency reliability of the subscales were Cronbach’s α

state = 0.94 and Cronbach’s α

trait = 0.93, respectively. Before administering the test, the researcher reminded the participants that there were differences between the subscales.

The Monetary Choice Questionnaire [

31] was used to measure participants' preferences in the context of intertemporal decision-making. The questionnaire consists of 27 items divided into the 3 groups of large reward (L), medium reward (M), and small reward (S); each group features 9 items. Participants were required to choose one of the SS and LL options. The questionnaire uses the discounting rate k as an indicator. The larger the value of

k is, the more impulsive the individual's behaviour, and the easier it is for the individual to choose a small and immediate reward. The reward and delay times for the items are different, but the discounting rate for one item in each of the three groups is the same. It is worth noting, considering the fact that the state anxiety and trait anxiety inventory may have similar meanings in terms of item content, that the participants completed the state anxiety inventory first, followed by the intertemporal decision-making task, and finally the trait anxiety inventory.

2.1.3. Data Analysis

The discounting rate

k is calculated using the method developed by Kibury [

31]. First, we use the formula

k = (LL/SS-1)/Delay to calculate the undifferentiated

k for choosing a smaller amount versus a larger amount per item [

32]. The Delay factor included in the formula indicates delay time. Second, the three groups of questions are sorted in descending order according to the undifferentiated

k value. The change in the participants' choice is the interval over which

k falls, and the geometric mean of the

k values of the two items is taken to represent the discounting rate of the participants. If multiple choice changes occur within a group,

k is estimated using the Bayesian formula [

33]. Finally, the geometric mean of the three groups of discounting rates is taken as the final

k of the participants. Since the value of

k does not conform to a normal distribution (

Skew = 4.45,

Kurt = 23.04),

k is log-transformed and recorded as

k' (

Skew = 0.01,

Kurt = -0.66) [

12].

Independent sample t test was used to examind the differences of gender and age in each variable. State anxiety exhibited significant gender differences (t(169) = –2.32, p = 0.02, d = 0.37) and age differences (F(1,9) = 2.02, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.10). The age difference in trait anxiety was marginally significant (F(1,9) = 2.02, p = 0.053, ηp2 = 0.10). The remaining variables exhibited no significant differences (ps > 0.05). Therefore, gender and age were used as control variables in this study.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 8.0 software. All regression coefficients were tested using the bootstrap method, and the theoretical model was tested by sampling 5000 times with a 95% confidence interval.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

The results of the description and correlation analyses indicated (see

Table 1) significant positive correlations among state anxiety, trait anxiety and discounting rate. It is consistent with the basic requirements of constructing a moderation model.

2.2.2. The Effect of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-Making: A Moderation Model Test for Trait Anxiety

The collinearity test found that the VIFs were all less than 5, which proved that there was no collinearity problem in this study.

In accordance with the procedures of the moderation analysis, base model was constructed to assess the direct predictive effects of state anxiety and trait anxiety on discounting rate. The results indicated the base model fits well (see

Table 2). State anxiety positively predicted the discounting rate (

β = 0.66,

t = 4.66,

p < 0.001). The remaining variables were not predictive in this context (

ps > 0.05).

Then, the moderating model was constrcuted fitting well(see

Table 2,

Table 3 and

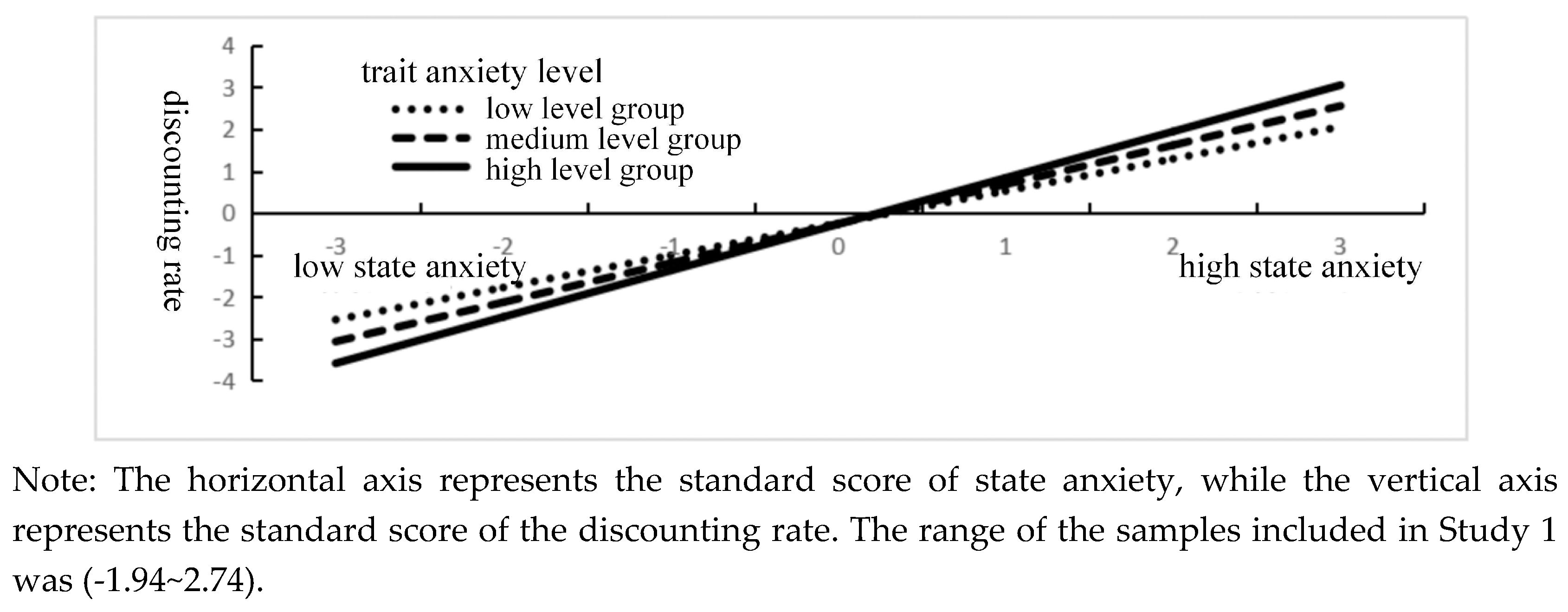

Table 4). According to the moderating model, state anxiety positively predicted the discounting rate (

β = 0.65,

t = 4.77,

p < 0.001), and the state anxiety × trait anxiety term also significantly predicted the discounting rate (

β = 0.19,

t = 2.73,

p = 0.01), indicating that trait anxiety could moderate the predictive effect of state anxiety on the discounting rate. Simple effects tests showed that higher trait anxiety in individuals were associated with a stronger predictive effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making (see

Figure 5). The remaining variables were not predictive in this context (

ps > 0.05).

Table 2.

The effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making: A moderatinon model test for trait anxiety.

Table 2.

The effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making: A moderatinon model test for trait anxiety.

| |

Regression equation (N=171) |

Fit metrics |

Coefficient significance |

| Outcome variable |

Predictor variable |

χ2 |

df |

Log(L) |

AIC |

BIC |

β |

t |

R2 |

| Base model |

Discounting rate |

|

63.07 |

4 |

–211.10 |

434.20 |

453.05 |

|

|

0.31 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.07 |

-1.04 |

|

| Age |

|

-0.04 |

-0.56 |

|

| State anxiety |

|

0.66***

|

4.66 |

|

| Trait anxiety |

|

-0.11 |

-0.68 |

|

| Moderation model |

Discounting rate |

|

71.05 |

5 |

–207.11 |

428.22 |

450.22 |

|

|

0.34 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.10 |

-1.56 |

|

| Age |

|

-0.06 |

-0.95 |

|

| State anxiety |

|

0.65***

|

4.77 |

|

| Trait anxiety |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.07 |

-0.43 |

|

| State anxiety ×Trait anxiety |

|

|

|

|

|

0.19**

|

2.73 |

|

Table 3.

Moderation effects of trait anxiety.

Table 3.

Moderation effects of trait anxiety.

| Trait anxiety |

State anxiety→ Discounting rate |

LCI |

UCI |

|

M–1SD

|

0.491*

|

0.25 |

0.75 |

| M |

0.653*

|

0.41 |

0.89 |

|

M+1SD

|

0.815*

|

0.53 |

1.08 |

Table 4.

The means and standard deviations of the correct rate and reaction time as well as the correct rate cost and reaction time cost (M±SD).

Table 4.

The means and standard deviations of the correct rate and reaction time as well as the correct rate cost and reaction time cost (M±SD).

| Groups |

Accuracy |

Accuracycost

|

RT |

RTcost

|

| Standard stimulus |

0.99 ± 0.01 |

0.06 ± 0.06 |

417.64 ± 51.26 |

21.70 ± 30.18 |

| Deviation stimulus |

0.94 ± 0.06 |

439.34 ± 47.29 |

Figure 4.

The effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making: A model diagram of the moderating role of trait anxiety.

Figure 4.

The effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making: A model diagram of the moderating role of trait anxiety.

Figure 5.

The moderating role of trait anxiety in the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making.

Figure 5.

The moderating role of trait anxiety in the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making.

2.3. Summary

The results of Study 1 supported Hypothesis 1, i.e., that trait anxiety moderates the predictive ability of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making. Specifically, in individuals with higher trait anxiety, state anxiety is more predictive of intertemporal decision-making and vice versa. In Study 2, inhibitory control factors were included to explore their mediating role in the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making.

3. Study 2: The Effect of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-making: A Moderated Mediating Model of Trait Anxiety and Inhibitory Control

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

Based on the power analysis by G*Power program(effect size f2 = 0.20, power = 0.80, α = 0.05), the minimum sample size required is 80. A total of 95 college students in Zhejiang University of Technology were recruited via their campus bulletin board in February 2022, including 55 females, with an average age of 21.00 years old (SD = 1.63). This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University of Technology in Hangzhou, China (ethics approval number: zjut202104735001-2). All the participants signed informed consent forms prior to participating in the study.

3.1.2. Procedure

The participants first completed the state anxiety inventory (consistency reliability Cronbach’s α

state = 0.88), followed by the intertemporal decision-making task (the same task as used in Study 1) and the two-choice oddball paradigm [

17], and finally the trait anxiety inventory (consistency reliability Cronbach’s α

trait = 0.85). The two-choice oddball paradigm can measure sensitive behavioral indicators of suppression control [

17].The experimental programme for the two-choice oddball paradigm was developed in E-prime 2.0 (see

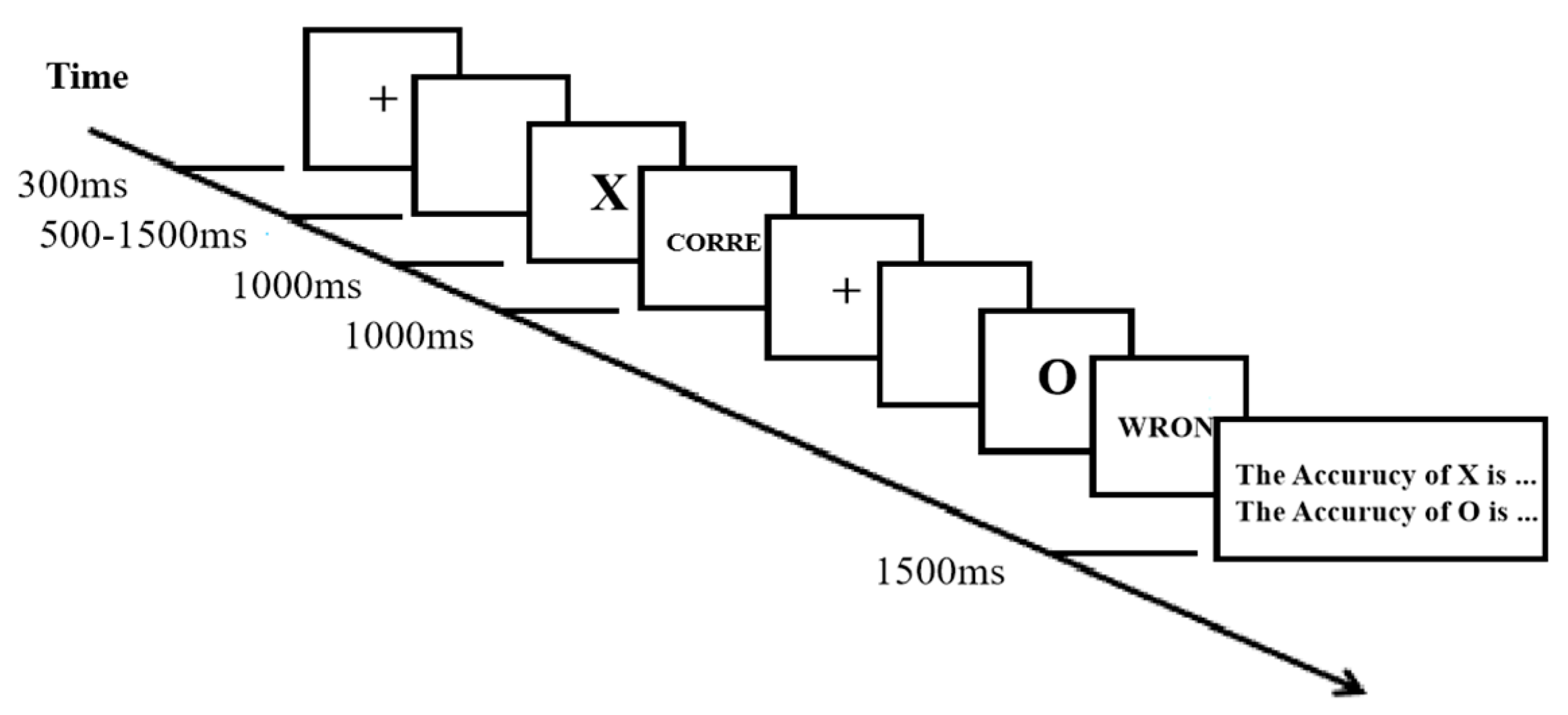

Figure 6). After beginning the experiment, the red fixation was first presented in the centre of the screen for 300 ms, and after the presentation of a blank screen for 500-1500 ms, either “X” (the standard stimulus, which appeared 75% of the time) or “O” (the deviation stimulus, which appeared 25% of the time) was presented in the same position. The participants were asked to press the "f" key if the stimulus was “X” and the “J” key if the stimulus was “O”. They were required to provide correct responses as soon as possible, specifically within 1000 ms. Finally, feedback was presented for 1000 ms. The formal experiment included 100 trials, and following every 10 trials, the correct rates of the two types of stimulus response were presented for 1500 ms in the centre of the screen as feedback. During the practice phase, the participants were required to complete 8 trials using the same process as in the formal experiment, and the formal experiment could be completed only after the correct response rate reached 100%.

3.1.3. Data Analysis

In the two-choice oddball paradigm, Accuracy

cost = Accuracy

standard stimulus - Accuracy

deviation stimulus, and RT

cost = RT

standard stimulus - RT

deviation stimulus. This study required the participants to respond with a sufficient level of practice to ensure the correct rate. The participants responded to both stimuli with more than 90% accuracy in the formal experiment, the average of standard stimulus response accuracy was 99% (as shown in

Table 4). The accuracy cost as inhibitory control indicators might not be accurate, as there might be some ceiling effect. Therefore, the response time cost was used as an index to measure inhibitory control. The larger the response time cost is, the weaker the participant’s inhibitory control ability.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 8.0 software. All regression coefficients were tested using the bootstrap method, and the theoretical model was tested by sampling 5000 times with a 95% confidence interval.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Correlation Analysis of Discounting Rate, Inhibitory Control, State Anxiety and Trait Anxiety

The descriptive statistics and correlation analysis showed (see

Table 5) that state anxiety, trait anxiety, inhibitory control and discounting rate were all significantly positively correlated. It is consistent with the basic requirements of constructing a mediation model.

3.2.2. The Effect of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-making: A Moderated Mediation Model Test of Trait Anxiety and Inhibitory Control

The collinearity test found that the VIFs were all less than 5, which proved that there was no collinearity problem in the study.

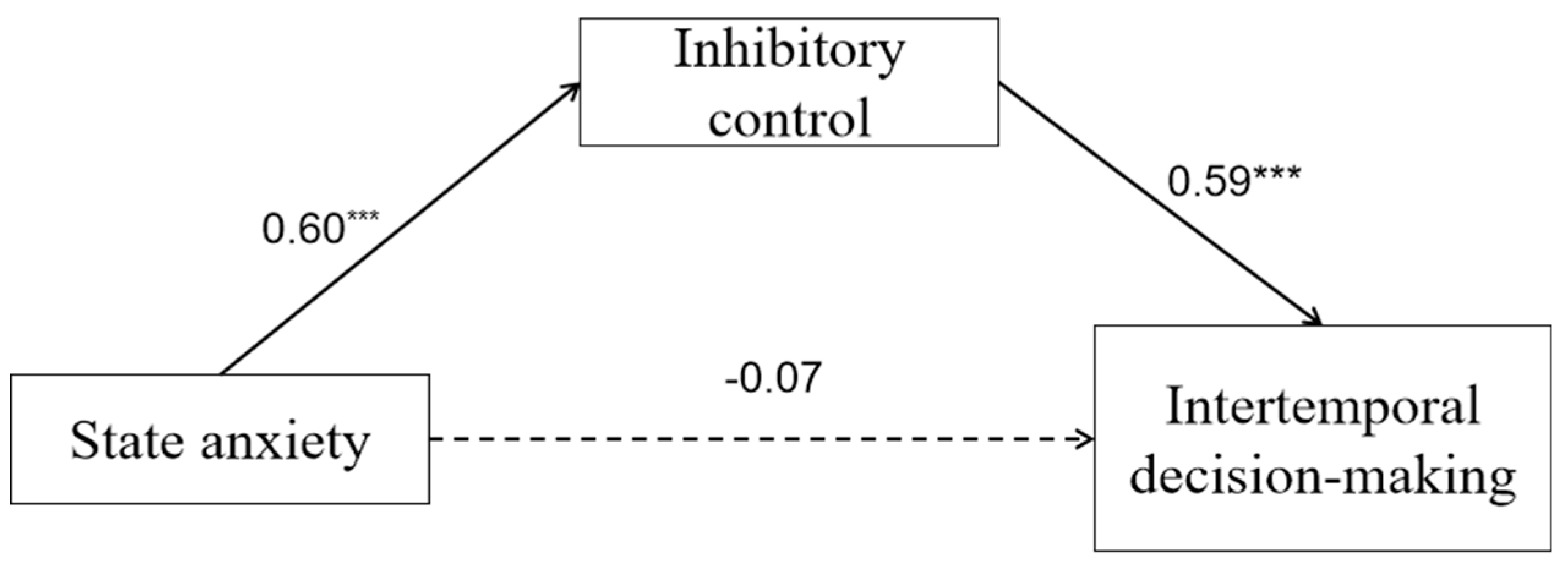

First, the mediating effect test of inhibitory control is shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7 as well as

Figure 7. According to the base model, state anxiety directly predicted the discounting rate (

β = 0.29,

t = 2.80,

p = 0.004). When the mediating variable inhibitory control was included in the mediation model, the direct prediction effect mentioned above became nonsignificant (

p > 0.05). In contrast, state anxiety predicted inhibitory control (

β = 0.60,

t = 9.13,

p < 0.001), and inhibitory control predicted the discounting rate (

β = 0.59,

t = 5.04,

p < 0.001). In addition, the upper and lower bounds of the bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of inhibitory control did not contain 0 (see

Table 7), thus indicating that inhibitory control was capable of playing a complete mediating role with respect to the predictive effect of state anxiety on the discounting rate.

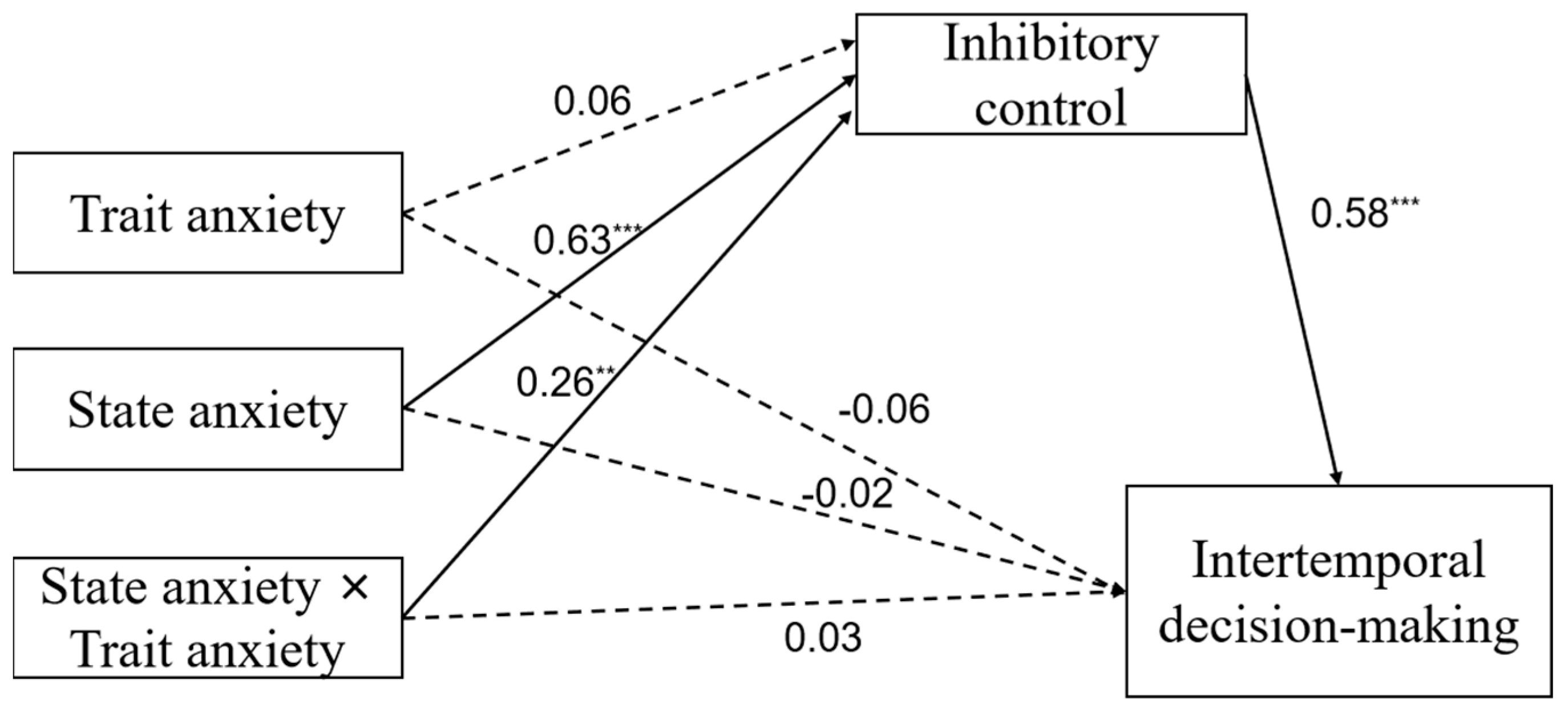

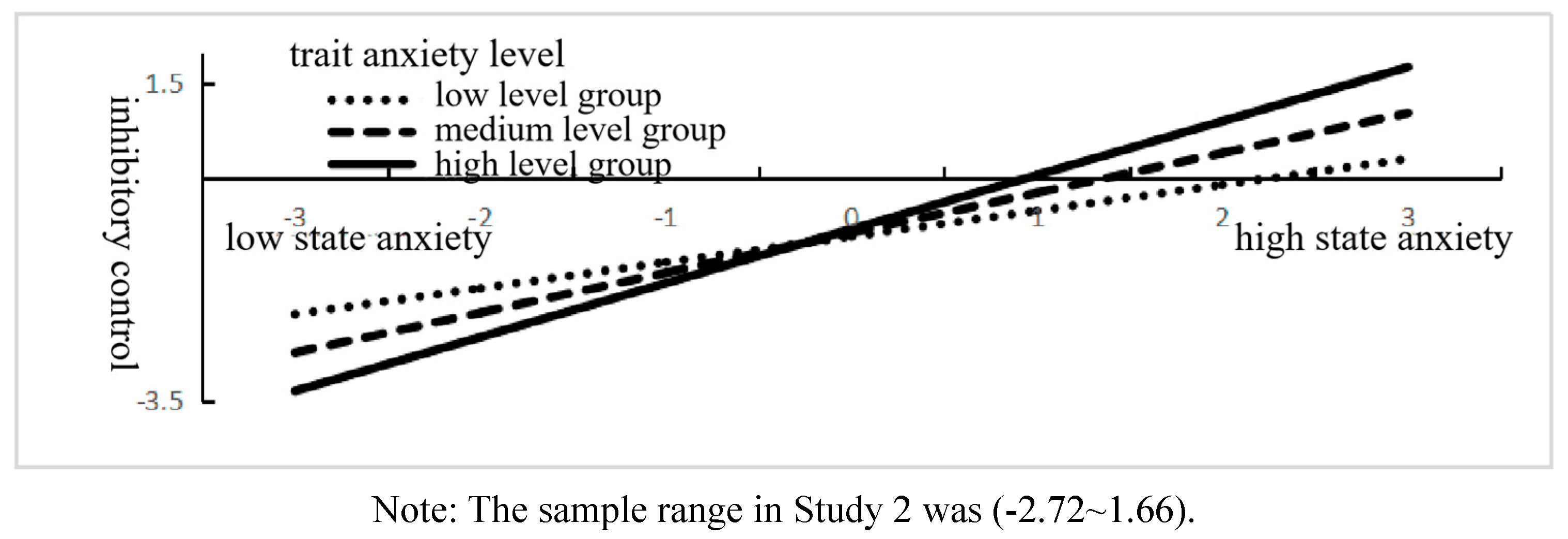

Second, the moderating effect of trait anxiety was tested on the basis of the mediation model, and the results are shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9 as well as

Figure 8. After incorporating trait anxiety into the model, the state anxiety × trait anxiety term was able to predict inhibitory control (

β = 0.26,

t = 3.00,

p = 0.003) but not to predict the discounting rate directly (

p > 0.05), thus indicating that trait anxiety could play only a moderating role with respect to the predictive effect of state anxiety on inhibitory control. Simple slope analysis showed (see

Figure 9) that higher trait anxiety it participants was associated with a greater predictive effect of state anxiety on inhibitory control and that inhibitory control had a stronger mediating effect on the relationship between state anxiety and discounting rate (see

Table 9).

3.3. Summary

The results of Study 2 supported Hypotheses 2 and 3 and found that inhibitory control played a complete mediating role in the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making; that is, state anxiety affected intertemporal decision-making by altering inhibitory control ability. The study further found that for individuals with higher trait anxiety, the mediating effect of inhibitory control on the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making increased.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-making: The Moderating Effects of Trait Anxiety

Study 1 found that state anxiety positively predicted individuals' intertemporal decision-making, which was consistent with the findings reported by Hanies [

11]. That is, the higher the state anxiety of the individual is, the higher the discounting rate of the intertemporal decision-making task, and the more inclined the individual is to choose the immediate beneficial SS. Namely, when individuals experience emotional states such as anxiety and worry, they tend to avoid these negative emotions and hope to end the events that induce the above emotions more quickly [

34], so they are more inclined to choose SS.

The study also found that, as a personality trait, trait anxiety could not directly predict intertemporal decision-making but also that it did affect such decision-making by interacting with state anxiety, which is basically consistent with the findings reported by Zhao [

15]. Trait anxiety affects the predictive power of state anxiety with respect to intertemporal decision-making. On the one hand, the state anxiety exhibited by individuals with higher trait anxiety is more predictive of intertemporal decision-making. These individuals are more impulsive and choose smaller-sooner gains when they experience high levels of state anxiety. Previous studies have shown that individuals with high trait anxiety are prone to have negative expectations regarding future events [

35], are more inclined to choose SS when making decisions [

36], and exhibit stronger brain activation [

14]. When they are in a high state of anxiety, the increasing uncertainty of the environment and the emergence of self-defeating behaviours (such as self-interest) prompts them to be more impulsive, and so they tend to choose smaller-sooner gains [

37]. On the other hand, state anxiety in individuals with lower trait anxiety was less predictive of intertemporal decision-making. The findings reported by Patt support this finding. Those authors recruited participants with lower trait anxiety and state anxiety than the standard sample and found no association between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making [

12]. In addition, this study found that state anxiety and trait anxiety have a stronger correlation, which may be due to the close link between the two concepts. Trait anxiety refers to a stable trait indicating that individuals are more likely to be anxious when encountering a situation, while state anxiety refers to immediate anxiety. From daily experience, in the same situation, people who easily become nervous may have higher levels of anxiety than those who are less nervous[

27].

4.2. The Effect of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-Making: The Mediating Effect of Inhibitory Control

Study 2 found that inhibitory control completely mediated the effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making. High state anxiety impairs individuals’ inhibitory control, prompting them to make intertemporal decisions that are less rewarding. Consistent with previous findings, an immediate increase in an individual's state anxiety leads to impaired inhibitory control [

13,

38]. Namely, according to the motivational dimensional model of affect [

9], high avoidance negative emotions such as anxiety narrow the individual’s range of attention [

39,

40] and thus cause the individual to focus cognitive resources on target stimuli, thereby reducing cognitive flexibility and temporarily depleting cognitive ability [

10].

Meanwhile, the impairment of inhibitory function affects the individual's control of inappropriate and impulsive behaviours, further encouraging impulsive and risk-taking behaviours in the context of intertemporal decision-making. Previous studies have also found that adolescents’ discounting rate of monetary rewards gradually decreases as they age, and the gradual improvement of their inhibitory control ability plays a key role in this process [

19]. Gamblers who are addicted to lottery tickets face the same situation. Some studies have found that these individuals’ lower-than-average delay discounting rate is caused by their lower inhibitory control ability [

20]. Overall, state anxiety predicts intertemporal decision-making via inhibitory control.

4.3. The Effect of State Anxiety on Intertemporal Decision-Making: The Moderated Mediating Effects of Trait Anxiety and Inhibitory Control

Study 1 found that trait anxiety has a moderating effect on the relationship between state anxiety and intertemporal decision-making. However, Study 2 found that in the moderated mediating effect model, the moderating effect of trait anxiety on the direct pathway was not significant. This finding suggests that the direct predictive effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making is not easily affected by the individual’s level of trait anxiety. This lack of effect may be due to the fact that according to the moderated mediation model, state anxiety does not have a significant direct predictive effect on intertemporal decision-making, and it affects intertemporal decision-making entirely via the mediating effect of inhibitory control. Study 2 also found that trait anxiety predicts intertemporal decision-making by modulating the effect of state anxiety on inhibitory control. The specific manifestation of this influence lies in the fact that high state anxiety reduces the inhibitory control of individuals with high trait anxiety, causing them to make impulsive intertemporal decisions. This model may be more representative of the true role of trait anxiety with respect to predicting the effect of state anxiety on intertemporal decision-making.

Most previous studies have found that the impairment of inhibitory control is the result of the temporary depletion of state anxiety or the stable characteristics of trait anxiety. The results of this study further support the claim that the impairment of inhibitory control is the result of the combined effect of these two factors. Similar to the findings reported by Myles [

13], Study 2 found that state anxiety and trait anxiety interactively predicted inhibitory control. A possible reason for this finding is that individuals with high trait anxiety have deficits with respect to their inhibitory control ability [

41], and an increase in state anxiety also temporarily impairs inhibitory control, thereby exacerbating the inhibitory control deficits exhibited by individuals with high trait anxiety. Meanwhile, Blakemore and Robbins argued that individuals’ decision-making involves interactions among several processes, including inhibitory control [

19]. Studies have also found that changes in the activity of certain brain regions related to cognitive control networks in addicts are associated with increased immediate reward preferences [

42,

43]. Therefore, cognitive control ability plays an important role in individuals’ intertemporal decision-making processes. Overall, these results indicate that individuals’ intertemporal decision-making is affected by a combination of cognitive and emotional factors.

4.4. Limitations and future direction

However, there are some limitations to this study. For example, when measuring state anxiety, trait anxiety, inhibitory control, and intertemporal decision-making, this article did not use any control or manipulation approach. Although this can explore the relationships between variables under natural conditions, the results reflect the correlation relationship. Future studies may consider using the task to induce the anxiety of participates and further verify the causal relationship by comparing the changes of inhibition control and intertemporal decision-making before and after the task, or establishing a model. In addition, this study has obtained results at the behavioral level so far. In the future, multi-level techniques (such as physiological multi-conduction, EEG, etc.) can be used to indicate the real-time state anxiety level of the subjects in the form of multiple indexes (comprehensive EEG and physiological indicators of the subjects), divide different time zones, and investigate its impact on intertemporal decision-making, which can make the study more ecological validity.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the questionnaire method and the experimental method were used to investigate the influence of state and trait anxiety on individual intertemporal decision-making as well as the role of inhibitory control in this process, and the following conclusions and implication were obtained: 1) Anxiety makes people impulsive. Better to wait for emotions get stable; 2) The ability to inhibit behavior will be reduced, when in an anxious state; 3) The higher the trait anxiety, the stronger the two effects above; 4) When anxious and ability to inhibit behavior limited, it’s easy to make impulsive decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X., J.J., Y.Y., & B.S.; Methodology, Y.X., J.J., Y.Y., & B.S.; Formal analysis, Y.X., & Y.Y.; Investigation, Y.X., J.J., & Y.Y.; Data curation, Y.X., & Y.Y.; Writing-original draft, Y.X.; Writing-review & editing, Y.X., J.J., & Y.Y.; Funding acquisition.Y.X.; Resources, B.S.; Supervision, B.S.; Project administration B.S.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (21NDQN209YB) and Preliminary Research Project in Humanities and Social Sciences of ZJUT (SKY-ZX-20200146).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the recommendations of the Human Research Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University of Technology.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participates involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O'donoghue, T. Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. J Econ Lit. 2002, 40, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cheng, Y.; Xie, Z.; Gong, N.; Liu, L. The influence of anger on delay discounting: The mediating role of certainty and control. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2021, 53, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Peng, Y.; Xiong, G. Are pregnant women more foresighted? The effect of pregnancy on intertemporal Choice. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2015, 47, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Zauberman, G. Can victoria's secret change the future? A subjective time perception account of sexual-cue effects on impatience. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012, 142, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, J.H.; Kim, H.E.; Sohn, S.; Seok, J.W.; Choi, D.; Watanuki, S. Effect of emotional arousal on inter-temporal decision-making: an fMRI study. J Physiol Anthropol, 2015, 34, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, H. Concept, measurement, antecedents and consequences of the effect of emotion on intertemporal choice. Adv Psychol Sci. 2019, 27, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Steno, D.; Li, Y.; Dickens, L.; Lerner, J.S. Gratitude: A tool for reducing economic impatience. Psychol Sci. 2014, 25, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.S.; Li, Y.; Weber, E.U. The financial costs of sadness. Psychol Sci. 2013, 24, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, P.; Harmon-Jones, E. The motivational dimensional model of affect: Implications for breadth of attention, memory, and cognitive categorisation. Cogn Emot. 2010, 24, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lv, Y. The neural mechanism of high and low avoidance negative emotions affecting inhibition: An ERP study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019, 17, 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, N.; Beauchaine, T.; Galdo, M.; Rogers, A.; Hahn, H.; Pitt, M.; Myung, J.; Turner, B.; Ahn, W. Anxiety Modulates Preference for Immediate Rewards Among Trait-Impulsive Individuals: A Hierarchical Bayesian Analysis. Clin Psychol Sci. 2020, 8, 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patt, V.M.; Hunsberger, R.; Jones, D.A.; Keane, M.M.; Verfaellie, M. Temporal discounting when outcomes are experienced in the moment: Validation of a novel paradigm and comparison with a classic hypothetical intertemporal choice task. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0251480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, O.; Grafton, B.; MacLeod, C. Anxiety & inhibition: dissociating the involvement of state and trait anxiety in inhibitory control deficits observed on the anti-saccade task. Cogn Emot. 2020, 34, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Gu, R.; Zhang, D.; Luo, Y. Anxious individuals are impulsive decision-makers in the delay discounting task: an ERP study. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Cheng, J.; Harris, M.; Vigo, R. Anxiety and inter-temporal decision making: the effect of the behavioral inhibition system and the moderation effects of trait anxiety on both state anxiety and socioeconomic status. Pers Individ Differ. 2015, 87, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; He, J.; Li, A. Upward social comparison on social network sites and impulse buying: A moderated mediation model of negative affect and rumination. Comput Hum Behav. 2019, 96, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Xu, M.; Yang, J.; Li, H. The application of the two-choice oddball paradigm to the research of behavior inhibitory control. Scientia sinica vitae. 2017, 47, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Zhou, R. The current status and controversy of inhibitory control deficits in anxiety: A perspective from attentional control theory. Adv Psychol Sci. 2019, 27, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, Sarah-Jayne, Robbins, Trevor, W. Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nat Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, X. Impaired decision making is associated with poor inhibition control in nonpathological lottery gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 2014, 31, 1617–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Feng, T. The neural substrates responsible for how trait anxiety affects delay discounting: Right hippocampal and cerebellar connectivity with bistable right inferior parietal lobule. Psychophysiology. 2020, 57, e13495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basten, U.; Stelzel, C.; Fiebach, C.J. Trait anxiety modulates the neural efficiency of inhibitory control. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011, 23, 3132–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, T.; Derakshan, N. The neural correlates of cognitive effort in anxiety: Effects on processing efficiency. Biol Psychol. 2011, 86, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, W.X.; Yang, H. Similar but not quite the same: Differential unique associations of trait fear and trait anxiety with inhibitory control. Pers Individ Differ. 2020, 155, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari BA, Koster E, Derakshan N. The effects of active worrying on working memory capacity. Cogn Emot. 2017, 9931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakshan, N.; Ansari, T.L.; Hansard, M.; Shoker, L.; Eysenck, M.W. Anxiety, inhibition, efficiency, and effectiveness: An investigation using the antisaccade task. Exp Psychol, 2009, 56, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. 1983.

- Bai, X.; Jia, L.; Wang, J. Emotional priming effects on difficult Stroop task for trait anxiety. J Psychol Sci. 2016, 39, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Qi, C.; Sang, B. The effect of automatic emotion regulation strategies on stress reaction of trait anxiety undergraduates. J Psychol Sci. 2019, 42, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. Effects of anxiety and depression on attentional bias: The mediating role attentional control. Studies of Psychology and behavior. 2020, 18, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, K.N.; Petry, N.M.; Bickel, W.K. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol. 1999, 128, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commons, M.L.; Mazur, J.E.; Nevin, J.A.; Rachlin, H. The effect of delay and of intervening events on reinforcement value, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. 1987.

- Scheibehenne, B.; Pachur, T. Using Bayesian hierarchical parameter estimation to assess the generalizability of cognitive models of choice. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2015, 22, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.M.; Chen, S.; Zhao, D.; Rao, L.L.; Liang, Z.Y.; Li, S. Pain now or later: An outgrowth account of pain-minimization. PloS One. 2015, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miloyan, B.; Bulley, A.; Suddendorf, T. Episodic foresight and anxiety: Proximate and ultimate perspectives. Br J Clin Psychol. 2016, 55, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Xiao, W.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Miao, D. The impact of trait anxiety on self-frame and decision making. J Behav Decis Mak. 2014, 27, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leith, K.P.; Baumeister, R.F. Why do bad mood increase self-defeating behavior? Emotion, risk taking, and self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996, 6, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basanovic, J.; Kaiko, I.; MacLeod, C. Change in attentional control predicts change in attentional bias to negative information in response to elevated state anxiety. Cognit Ther Res. 2021, 45, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Gable, P.; Price, T.F. Does negative affect always narrow and positive affect always broaden the mind? Considering the influence of motivational intensity on cognitive scope. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013, 22, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.J.; Edwards, M.S.; Lyvers, M. Cognitive trait anxiety, situational stress, and mental effort predict shifting efficiency: Implications for attentional control theory. Emotion. 2015, 15, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; De Beuckelaer, A.; Chen, L.; Zhou, R. ERP Evidence for inhibitory control deficits in test-anxious individuals. Front Psychiatry. 2019, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedl, S.F.; Wiswede, D.; Marco-Pallarés, J.; Ye, Z.; Fehr, T.; Herrmann, M.; Münte, T.F. The neural basis of impulsive discounting in pathological gamblers. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2015, 9, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amlung, M.; Sweet, L.H.; Acker, J.; Brown, C.L.; MacKillop, J. Dissociable brain signatures of choice conflict and immediate reward preferences in alcohol use disorders. Addiction biology. 2014, 19, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).