Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

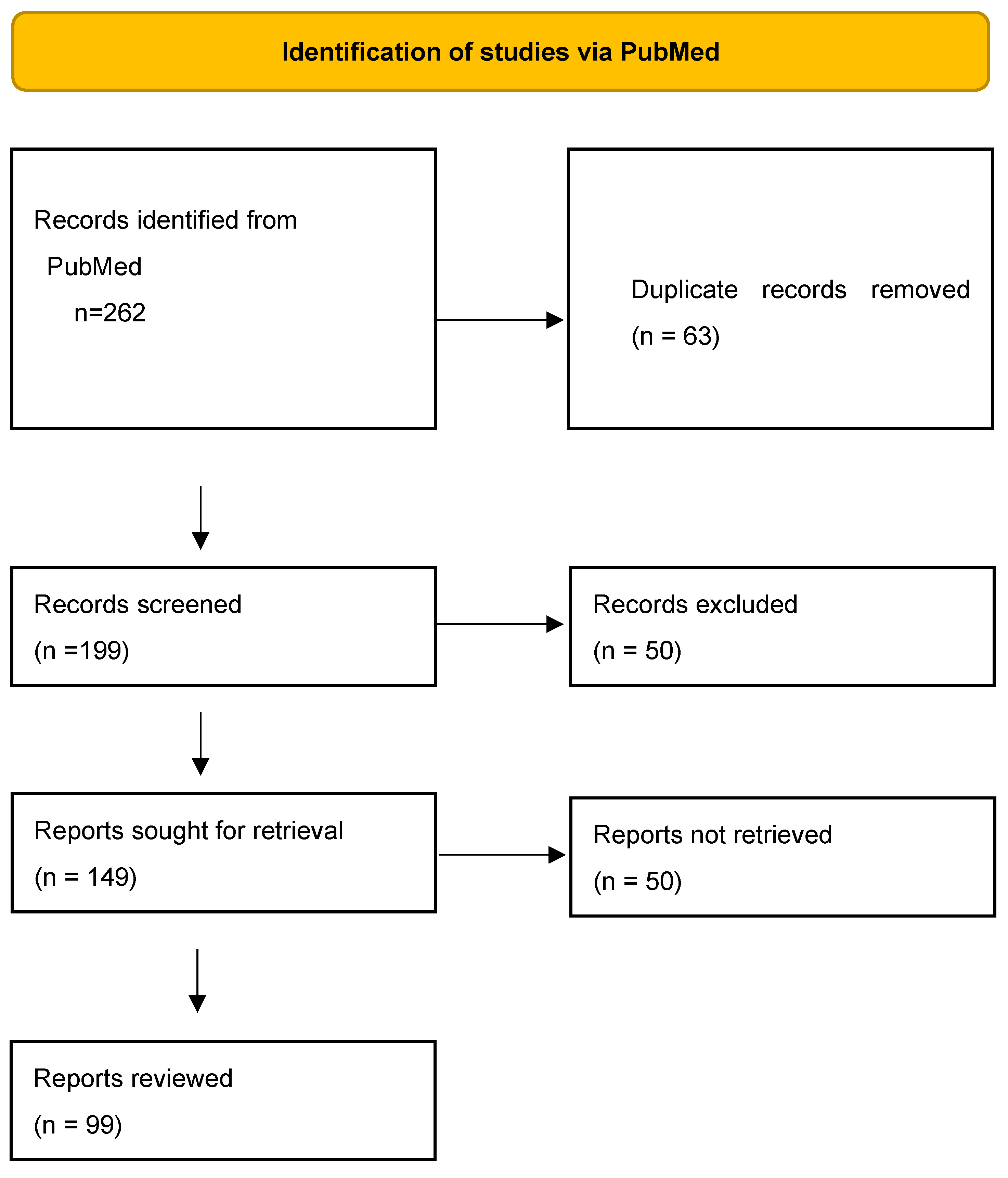

2. Methods

3. Systemic lupus erythematosus treatment

3.1. Antimalarials

3.2. Glucocorticoids

3.3. Azathioprine

3.4. Methotrexate

3.5. Mycophenolate mofetil

3.6. Cyclophosphamide

3.7. Calcineurin inhibitors

3.8. Intravenous immunoglobulin

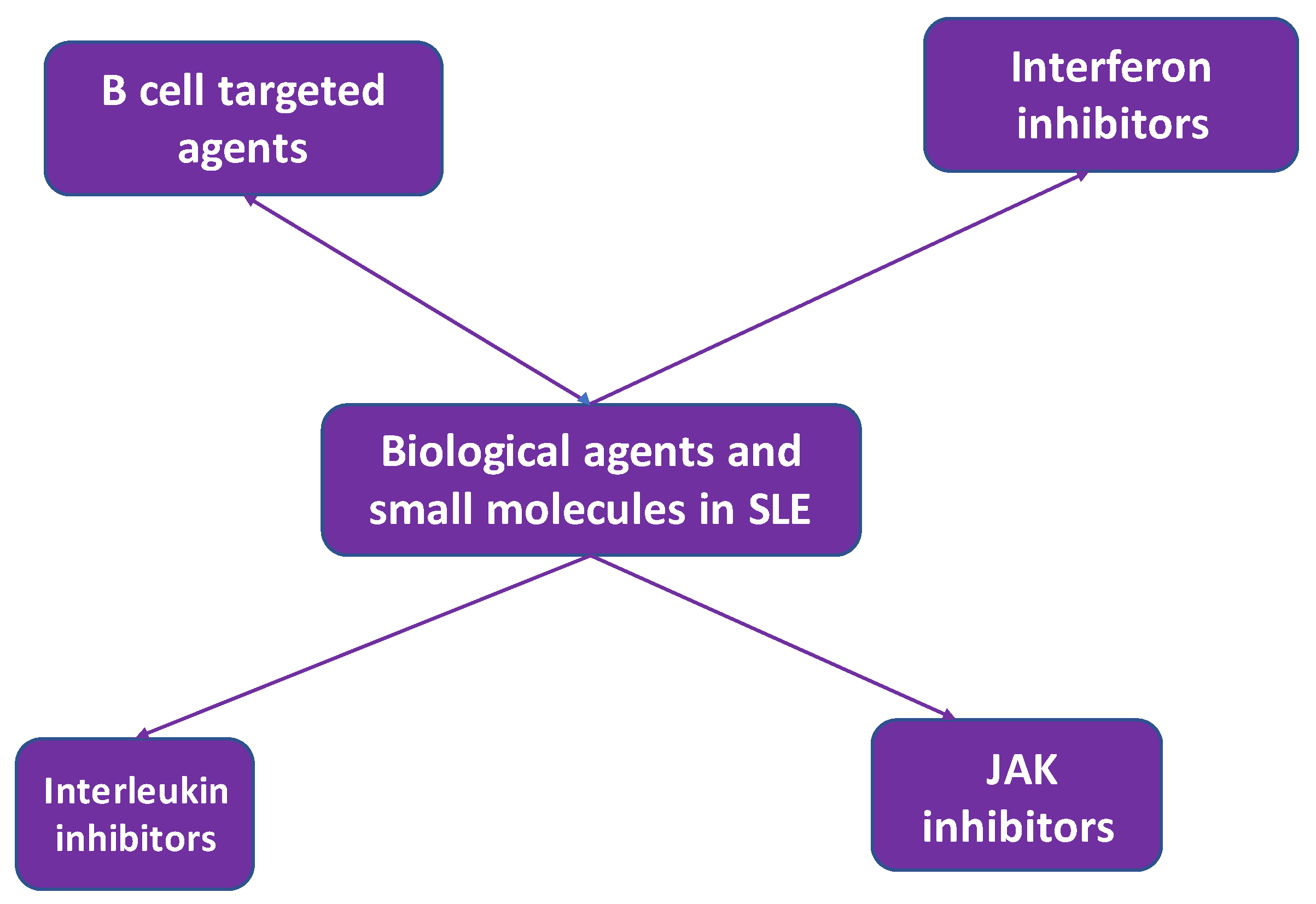

4. Biologic treatment in systemic lupus erythematosus

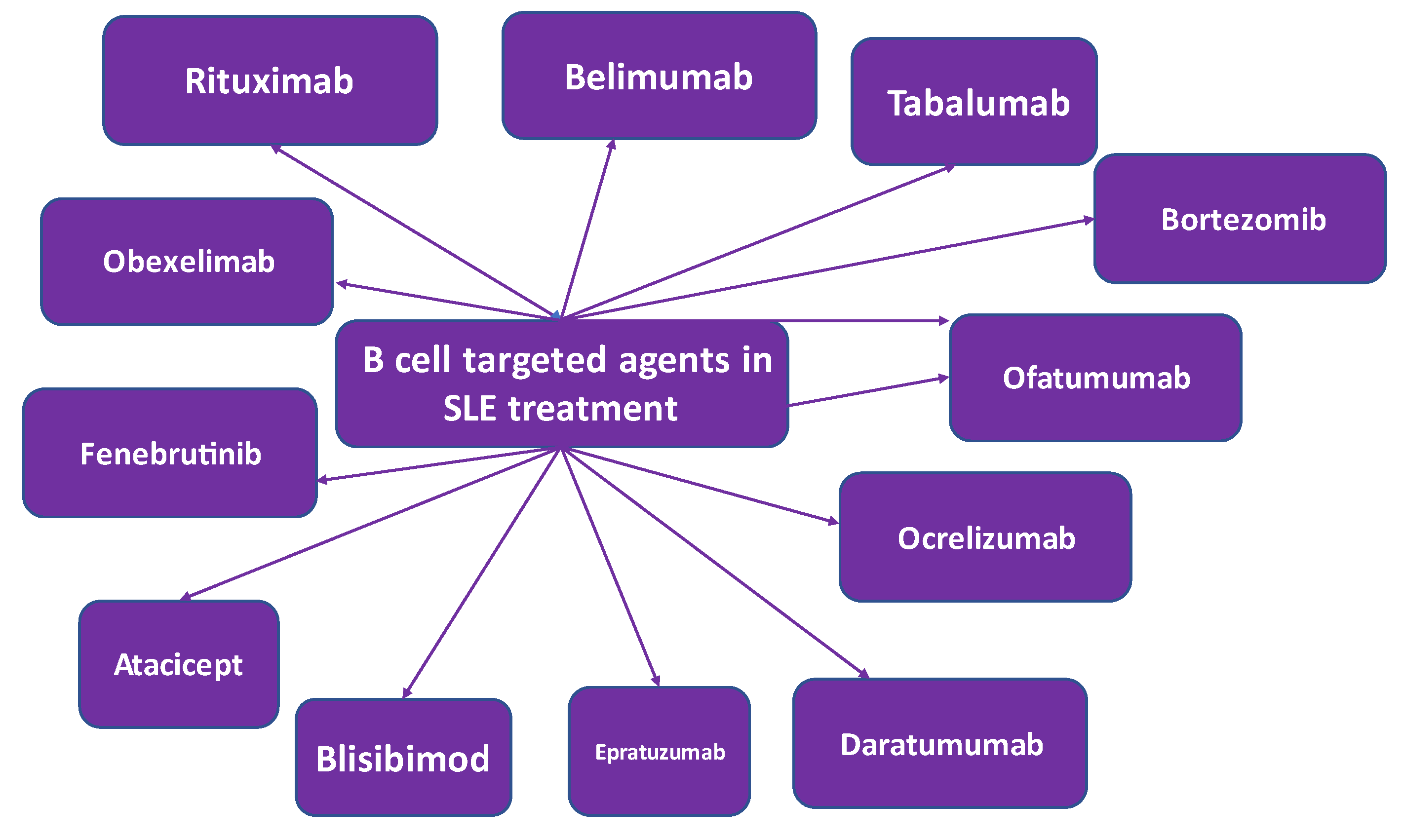

4.1. B cell targeted treatment

4.1.1. Rituximab

4.1.2. Belimumab

4.1.3. Tabalumab

4.1.4. Atacicept

4.1.5. Blisibimod

4.1.6. Epratuzumab

4.1.7. Daratumumab

4.1.8. Ocrelizumab

4.1.9. Obinutuzumab

4.1.10. Ofatumumab

4.1.11. Obexelimab

4.1.12. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase-Targeted Treatment

4.1.13. Proteasome Inhibitors

4.1.14. Rigerimod

4.2. Interferon inhibitors

4.2.1. Sifalimumab

4.2.2. Anifrolumab

4.4. Interleukin inhibitors

4.4.1. Tocilizumab

4.4.2. Secukinumab

4.5. JAK inhibitors

4.5.1. Baricitinib

5. Therapeutic strategies for the management of SLE

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rúa-Figueroa Fernández de Larrinoa, I. What is new in systemic lupus erythematosus. Reumatol Clin. 2015, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocampo-Piraquive V, Nieto-Aristizábal I, Cañas CA, Tobón GJ. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: causes, predictors and interventions. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018, 14, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Estel GJ, Ugarte-Gil MF, Alarcón GS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017, 13, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörner T, Furie R. Novel paradigms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2019, 393, 2344–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisnevskaia L, Murphy G, Isenberg D. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2014, 384, 1878–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna G, Brennan MT. Systemic lupus erythematosus: epidemiology, pathophysiology, manifestations, and management. Dent Clin North Am. 2013, 57, 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzler EM, Aranow C. Prevention and treatment of adverse effects of corticosteroids in systemic lupus erythematosus. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1998, 12, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vollenhoven RF, Mosca M, Bertsias G, et al. Treat-to-target in systemic lupus erythematosus: recommendations from an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014, 73, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho A, Delgado Alves J, Fortuna J, et al. Biological therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Sjögren’s syndrome: evidence- and practice-based guidance. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1117699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aringer M, Burkhardt H, Burmester GR, et al. Current state of evidence on ‘off-label’ therapeutic options for systemic lupus erythematosus, including biological immunosuppressive agents, in Germany, Austria and Switzerland--a consensus report. Lupus. 2012, 21, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsias GK, Tektonidou M, Amoura Z, et al. Joint European League Against Rheumatism and European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) recommendations for the management of adult and paediatric lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012, 71, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A randomized study of the effect of withdrawing hydroxychloroquine sulfate in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1991, 324, 150–154. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón GS, McGwin G, Bertoli AM, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine on the survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA L). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinjo SK, Bonfá E, Wojdyla D, et al. Antimalarial treatment may have a time-dependent effect on lupus survival: data from a multinational Latin American inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainsford KD, Parke AL, Clifford-Rashotte M, Kean WF. Therapy and pharmacological properties of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 2015, 23, 231–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James JA, Kim-Howard XR, Bruner BF, et al. Hydroxychloroquine sulfate treatment is associated with later onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007, 16, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer-Betz R, Schneider M. [Antimalarials. A treatment option for every lupus patient!?]. Z Rheumatol. 2009, 68, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, RI. Mechanism of action of hydroxychloroquine as an antirheumatic drug. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 23 (Suppl. 1), 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, R. Anti-malarial drugs: possible mechanisms of action in autoimmune disease and prospects for drug development. Lupus. 1996, 5 (Suppl. 1), S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrezenmeier E, Dörner T. Mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: implications for rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Irastorza G, Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Khamashta MA. Clinical efficacy and side effects of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, M. Use of hydroxychloroquine to prevent thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and in antiphospholipid antibody-positive patients. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011, 13, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floris A, Piga M, Mangoni AA, Bortoluzzi A, Erre GL, Cauli A. Protective Effects of Hydroxychloroquine against Accelerated Atherosclerosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 3424136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn SK, Kao AH, Schott LL, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and glycemia in women with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Irastorza G, Khamashta MA. Hydroxychloroquine: the cornerstone of lupus therapy. Lupus. 2008, 4, 271–273. [Google Scholar]

- Adamptey B, Rudnisky CJ, MacDonald IM. Effect of stopping hydroxychloroquine therapy on the multifocal electroretinogram in patients with rheumatic disorders. Can J Ophthalmol. 2020, 55, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. State-of-the-art treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020, 23, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta S, Danza A, Arias Saavedra M, et al. Glucocorticoids in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ten Questions and Some Issues. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun. 2019, 96, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, M. Long-term outcomes in lupus. Am J Manag Care. 2001, 7 (Suppl. 16), S480–S485. [Google Scholar]

- Jaryal A, Vikrant S. Current status of lupus nephritis. Indian J Med Res. 2017, 145, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra M, Sánchez A, Morales S, Ángeles U, Jara LJ. Azathioprine during pregnancy in systemic lupus erythematosus patients is not associated with poor fetal outcome. Clin Rheumatol. 2015, 34, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin PR, Abrahamowicz M, Ferland D, Lacaille D, Smith CD, Zummer M. Steroid-sparing effects of methotrexate in systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 1796–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muangchan C, van Vollenhoven RF, Bernatsky SR, et al. Treatment Algorithms in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015, 67, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksimovic V, Pavlovic-Popovic Z, Vukmirovic S, et al. Molecular mechanism of action and pharmacokinetic properties of methotrexate. Mol Biol Rep. 2020, 47, 4699–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam MN, Hossain M, Haq SA, Alam MN, Ten Klooster PM, Rasker JJ. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in articular and cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012, 15, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronstein BN, Aune TM. Methotrexate and its mechanisms of action in inflammatory arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani P, Ruscitti P, Carubbi F, Liakouli V, Giacomelli R. Methotrexate: an old new drug in autoimmune disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014, 10, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakthiswary R, Suresh E. Methotrexate in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of its efficacy. Lupus. 2014, 23, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom F, de Walle HE, van de Laar MA, Brouwers JR, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in pregnancy: current status and implications for the future. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 845–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broen JCA, van Laar JM. Mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine and tacrolimus: mechanisms in rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech E, Merrill JT. Mycophenolate mofetil for lupus nephritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2008, 4, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh M, James M, Jayne D, Tonelli M, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR. Mycophenolate mofetil for induction therapy of lupus nephritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007, 2, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris HK, Canetta PA, Appel GB. Impact of the ALMS and MAINTAIN trials on the management of lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013, 28, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair A, Appel G, Dooley MA, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil as induction and maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis: rationale and protocol for the randomized, controlled Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS). Lupus. 2007, 16, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houssiau FA, D’Cruz D, Sangle S, et al. Azathioprine versus mycophenolate mofetil for long-term immunosuppression in lupus nephritis: results from the MAINTAIN Nephritis Trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69, 2083–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoenoiu MS, Aydin S, Tektonidou M, et al. Repeat kidney biopsies fail to detect differences between azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis: data from the MAINTAIN Nephritis Trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012, 27, 1924–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginzler EM, Wofsy D, Isenberg D, Gordon C, Lisk L, Dooley MA. Nonrenal disease activity following mycophenolate mofetil or intravenous cyclophosphamide as induction treatment for lupus nephritis: findings in a multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel-group clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, CC. Mycophenolate mofetil for non-renal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007, 36, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel GB, Contreras G, Dooley MA, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D, et al. The 10-year follow-up data of the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial comparing low-dose and high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap DY, Chan TM. Lupus Nephritis in Asia: Clinical Features and Management. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2015, 1, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurd ER, Ziff M. The mechanism of action of cyclophosphamide on the nephritis of (NZB x NZW)F1 hybrid mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977, 29, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Fassbinder T, Saunders U, Mickholz E, et al. Differential effects of cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil on cellular and serological parameters in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin F, Lauwerys B, Lefèbvre C, Devogelaer JP, Houssiau FA. Side-effects of intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. Lupus. 1997, 6, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul C, Donnelly M, Merscher-Gomez S, et al. The actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes is a direct target of the antiproteinuric effect of cyclosporine A. Nat Med. 2008, 14, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pego-Reigosa JM, Cobo-Ibáñez T, Calvo-Alén J, et al. Efficacy and safety of nonbiologic immunosuppressants in the treatment of nonrenal systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013, 65, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunol Today. 1992, 13, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell G, Graveley R, Seid J, al-Humidan AK, Skjodt H. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine and effects on connective tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992, 21 (Suppl. 3), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, CC. Towards new avenues in the management of lupus glomerulonephritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao H, Liu ZH, Xie HL, Hu WX, Zhang HT, Li LS. Successful treatment of class V+IV lupus nephritis with multitarget therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008, 19, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Zhang H, Xing C, et al. Multitarget therapy for induction treatment of lupus nephritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015, 162, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronbichler A, Brezina B, Gauckler P, Quintana LF, Jayne DRW. Refractory lupus nephritis: When, why and how to treat. Autoimmun Rev. 2019, 18, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovin BH, Solomons N, Pendergraft WF, 3rd, et al. A randomized, controlled double-blind study comparing the efficacy and safety of dose-ranging voclosporin with placebo in achieving remission in patients with active lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodis I, Houssiau FA. From sequential to combination and personalised therapy in lupus nephritis: moving towards a paradigm shift? Ann Rheum Dis. 2022, 81, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin BH, Teng YKO, Ginzler EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of voclosporin versus placebo for lupus nephritis (AURORA 1): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021, 397, 2070–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthiswary R, D’Cruz D. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the therapeutic armamentarium of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014, 93, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro-Checa C, Zirkzee EJ, Huizinga TW, Steup-Beekman GM. Management of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Current Approaches and Future Perspectives. Drugs. 2016, 76, 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri V, Varma S, Joshi K, Malhotra P, Kumari S, Jain S. Lupus myocarditis: marked improvement in cardiac function after intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010, 30, 1503–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandman-Goddard G, Blank M, Shoenfeld Y. Intravenous immunoglobulins in systemic lupus erythematosus: from the bench to the bedside. Lupus. 2009, 18, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandman-Goddard G, Levy Y, Shoenfeld Y. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005, 29, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill JT, Neuwelt CM, Wallace DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in moderately-to-severely active systemic lupus erythematosus: the randomized, double-blind, phase II/III systemic lupus erythematosus evaluation of rituximab trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirone C, Mendoza-Pinto C, van der Windt DA, Parker B, M OS, Bruce IN. Predictive and prognostic factors influencing outcomes of rituximab therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017, 47, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata S, Saito K, Hirata S, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-CD20 antibody rituximab for patients with refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018, 27, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarra SV, Guzmán RM, Gallacher AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011, 377, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair HA, Duggan ST. Belimumab: A Review in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Drugs. 2018, 78, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh YJ, Baptista B, D’Cruz DP. Subcutaneous and intravenous belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of data on subcutaneous and intravenous administration. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017, 13, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace DJ, Ginzler EM, Merrill JT, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Belimumab Plus Standard Therapy for Up to Thirteen Years in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij T, Kamerling SWA, de Rooij ENM, et al. The NET-effect of combining rituximab with belimumab in severe systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2018, 91, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtierotti R, Borghi MO, Gerosa M, et al. Successful sequential therapy with rituximab and belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series. Clin Exp Rheumatol. Jul- 2018, 36, 643–647. [Google Scholar]

- Lee WS, Amengual O. B cells targeting therapy in the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Med. 2020, 43, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis LS, Reimold AM. Research and therapeutics-traditional and emerging therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017, 56 (suppl. 1), i100–i113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, R. Biological therapies and their clinical impact in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2019, 11, 1759720x19874309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samotij D, Reich A. Biologics in the Treatment of Lupus Erythematosus: A Critical Literature Review. Biomed Res Int. 2019, 2019, 8142368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma K, Du W, Wang X, et al. Multiple Functions of B Cells in the Pathogenesis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möckel T, Basta F, Weinmann-Menke J, Schwarting A. B cell activating factor (BAFF): Structure, functions, autoimmunity and clinical implications in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2021, 20, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbitman L, Furie R, Vashistha H. B cell-targeted therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2022, 132, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy E, Wax S, Huard B, Hess H, Schneider P. Targeting BAFF and APRIL in systemic lupus erythematosus and other antibody-associated diseases. Int Rev Immunol. 2017, 36, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen C, Laidlaw BJ. Development and function of tissue-resident memory B cells. Adv Immunol. 2022, 155, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabahi R, Anolik JH. B-cell-targeted therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs. 2006, 66, 1933–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap DYH, Chan TM. B Cell Abnormalities in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Lupus Nephritis-Role in Pathogenesis and Effect of Immunosuppressive Treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 3918–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrill JT, van Vollenhoven RF, Buyon JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tabalumab, a monoclonal antibody to B-cell activating factor, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from ILLUMINATE-2, a 52-week, phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016, 75, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg D, Gordon C, Licu D, Copt S, Rossi CP, Wofsy D. Efficacy and safety of atacicept for prevention of flares in patients with moderate-to-severe systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): 52-week data (APRIL-SLE randomised trial). Ann Rheum Dis. 2015, 74, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill JT, Shanahan WR, Scheinberg M, Kalunian KC, Wofsy D, Martin RS. Phase III trial results with blisibimod, a selective inhibitor of B-cell activating factor, in subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018, 77, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar S, Kahlenberg JM. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Annu Rev Med. 2023, 74, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Cheng Y, Ma S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus-complicating immune thrombocytopenia: From pathogenesis to treatment. J Autoimmun. 2022, 132, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg D, Furie R, Jones NS, et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Pharmacodynamic Effects of the Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Fenebrutinib (GDC-0853) in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Results of a Phase II, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 1835–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny T, Borisch B, Introna M, Johnson P, Rose AL. Mechanism of action of rituximab. Anticancer Drugs. 2002, 13 (Suppl 2), S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald V, Leandro M. Rituximab in non-haematological disorders of adults and its mode of action. Br J Haematol. 2009, 146, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, GJ. Rituximab: mechanism of action. Semin Hematol. 2010, 47, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz I, Lee FE. B cells as therapeutic targets in SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, I. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Extent and patterns of off-label use of rituximab for SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang CR, Tsai YS, Li WT. Lupus myocarditis receiving the rituximab therapy-a monocentric retrospective study. Clin Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals M, Soto MJ, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA. Rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review of off-label use in 188 cases. Lupus. 2009, 18, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnarsson I, Jonsdottir T. Rituximab treatment in lupus nephritis--where do we stand? Lupus. 2013, 22, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt M, Grunke M, Proft F, et al. Clinical outcomes and safety of rituximab treatment for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) - results from a nationwide cohort in Germany (GRAID). Lupus. 2013, 22, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Ibáñez T, Loza-Santamaría E, Pego-Reigosa JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in the treatment of non-renal systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 44, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga M, Saito K, Kawabata D, et al. Efficacy of rituximab (anti-CD20) for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus involving the central nervous system. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni G, Raffiotta F, Trezzi B, et al. Rituximab vs mycophenolate and vs cyclophosphamide pulses for induction therapy of active lupus nephritis: a clinical observational study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014, 53, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenstein MR, Wing C. The BAFFling effects of rituximab in lupus: danger ahead? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus MN, Turner-Stokes T, Chavele KM, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR. B-cell numbers and phenotype at clinical relapse following rituximab therapy differ in SLE patients according to anti-dsDNA antibody levels. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012, 51, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter LM, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR. Elevated serum BAFF levels are associated with rising anti-double-stranded DNA antibody levels and disease flare following B cell depletion therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 2672–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Lagares C, Croca S, Sangle S, et al. Efficacy of rituximab in 164 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis: pooled data from European cohorts. Autoimmun Rev. 2012, 11, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Mendez LM, Cascino MD, Garg J, et al. Peripheral Blood B Cell Depletion after Rituximab and Complete Response in Lupus Nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1502–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furie R, Rovin BH, Houssiau F, et al. Two-Year, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Belimumab in Lupus Nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vollenhoven RF, Petri MA, Cervera R, et al. Belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: high disease activity predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012, 71, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, W. Future prospects in biologic therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013, 9, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais SA, Vilas-Boas A, Isenberg DA. B-cell survival factors in autoimmune rheumatic disorders. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2015, 7, 122–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas A, Morais SA, Isenberg DA. Belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus. RMD Open. 2015, 1, e000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naradikian MS, Perate AR, Cancro MP. BAFF receptors and ligands create independent homeostatic niches for B cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015, 34, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent FB, Morand EF, Schneider P, Mackay F. The BAFF/APRIL system in SLE pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014, 10, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon SR, Harder B, Lewis KB, et al. B-lymphocyte stimulator/a proliferation-inducing ligand heterotrimers are elevated in the sera of patients with autoimmune disease and are neutralized by atacicept and B-cell maturation antigen-immunoglobulin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 12, R48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschke V, Sosnovtseva S, Ward CD, et al. BLyS and APRIL form biologically active heterotrimers that are expressed in patients with systemic immune-based rheumatic diseases. J Immunol. 2002, 169, 4314–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, W. Systemic lupus erythematosus and its ABCs (APRIL/BLyS complexes). Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 2, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerreiro Castro S, Isenberg DA. Belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): evidence-to-date and clinical usefulness. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017, 9, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plüß M, Tampe B, Niebusch N, Zeisberg M, Müller GA, Korsten P. Clinical Efficacy of Routinely Administered Belimumab on Proteinuria and Neuropsychiatric Lupus. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020, 7, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipa M, Embleton-Thirsk A, Parvaz M, et al. Effectiveness of Belimumab After Rituximab in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus : A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021, 174, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petricca L, Gigante MR, Paglionico A, et al. Rituximab Followed by Belimumab Controls Severe Lupus Nephritis and Bullous Pemphigoid in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Refractory to Several Combination Therapies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020, 7, 553075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij T, Arends EJ, van Dam LS, et al. Long-term effects of combined B-cell immunomodulation with rituximab and belimumab in severe, refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: 2-year results. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021, 36, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenberg DA, Petri M, Kalunian K, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tabalumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from ILLUMINATE-1, a 52-week, phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016, 75, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill JT, Wallace DJ, Wax S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Atacicept in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Results of a Twenty-Four-Week, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Arm, Phase IIb Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri MA, Martin RS, Scheinberg MA, Furie RA. Assessments of fatigue and disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus enrolled in the Phase 2 clinical trial with blisibimod. Lupus. 2017, 26, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenert A, Niewold TB, Lenert P. Spotlight on blisibimod and its potential in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: evidence to date. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017, 11, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geh D, Gordon C. Epratuzumab for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace DJ, Goldenberg DM. Epratuzumab for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2013, 22, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottenberg JE, Dörner T, Bootsma H, et al. Efficacy of Epratuzumab, an Anti-CD22 Monoclonal IgG Antibody, in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients With Associated Sjögren’s Syndrome: Post Hoc Analyses From the EMBODY Trials. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag-Ozbek A, Hui-Yuen JS. Emerging B-Cell Therapies in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostendorf L, Burns M, Durek P, et al. Targeting CD38 with Daratumumab in Refractory Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oon S, Huq M, Godfrey T, Nikpour M. Systematic review, and meta-analysis of steroid-sparing effect, of biologic agents in randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials for systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 48, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, YN. Ocrelizumab: A Review in Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs. 2022, 82, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mysler EF, Spindler AJ, Guzman R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ocrelizumab in active proliferative lupus nephritis: results from a randomized, double-blind, phase III study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 2368–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy V, Klein C, Isenberg DA, et al. Obinutuzumab induces superior B-cell cytotoxicity to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus patient samples. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017, 56, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy V, Dahal LN, Cragg MS, Leandro M. Optimising B-cell depletion in autoimmune disease: is obinutuzumab the answer? Drug Discov Today. 2016, 21, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan SU, Md Yusof MY, Emery P, Dass S, Vital EM. Biologic Sequencing in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: After Secondary Non-response to Rituximab, Switching to Humanised Anti-CD20 Agent Is More Effective Than Belimumab. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020, 7, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud S, McAdoo SP, Bedi R, Cairns TD, Lightstone L. Ofatumumab for B cell depletion in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who are allergic to rituximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018, 57, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford M, McCormack PL. Ofatumumab. Drugs. 2010, 70, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth F, Hinze C, Häfner R. Combination of ofatumumab and fresh frozen plasma in hypocomplementemic systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Lupus. 2018, 27, 1395–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu SY, Pong E, Bonzon C, et al. Inhibition of B cell activation following in vivo co-engagement of B cell antigen receptor and Fcγ receptor IIb in non-autoimmune-prone and SLE-prone mice. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021, 4, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satterthwaite, AB. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase, a Component of B Cell Signaling Pathways, Has Multiple Roles in the Pathogenesis of Lupus. Front Immunol. 2017, 8, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg N, Padron EJ, Rammohan KW, Goodman CF. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: The Next Frontier of B-Cell-Targeted Therapies for Cancer, Autoimmune Disorders, and Multiple Sclerosis. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozkiewicz D, Hermanowicz JM, Kwiatkowska I, Krupa A, Pawlak D. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (BTKIs): Review of Preclinical Studies and Evaluation of Clinical Trials. Molecules. 2023, 28, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander T, Sarfert R, Klotsche J, et al. The proteasome inhibitior bortezomib depletes plasma cells and ameliorates clinical manifestations of refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015, 74, 1474–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan CRC, Abdul-Majeed S, Cael B, Barta SK. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Bortezomib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra A, Arredondo KV, Jaramillo J, et al. Efficacy and safety of bortezomib in refractory lupus nephritis: a single-center experience. Lupus. 2020, 29, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walhelm T, Gunnarsson I, Heijke R, et al. Clinical Experience of Proteasome Inhibitor Bortezomib Regarding Efficacy and Safety in Severe Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Nationwide Study. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 756941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer R, Scherbarth HR, Rillo OL, Gomez-Reino JJ, Muller S. Lupuzor/P140 peptide in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013, 72, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnblom, L. The importance of the type I interferon system in autoimmunity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016, 34 (Suppl. 98), 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Khamashta M, Merrill JT, Werth VP, et al. Sifalimumab, an anti-interferon-α monoclonal antibody, in moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016, 75, 1909–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin A, Yasuda K, Cohen-Bucay A, et al. Monoallelic IRF5 deficiency in B cells prevents murine lupus. JCI Insight. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand EF, Trasieva T, Berglind A, Illei GG, Tummala R. Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) attainment discriminates responders in a systemic lupus erythematosus trial: post-hoc analysis of the Phase IIb MUSE trial of anifrolumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018, 77, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks ED. Anifrolumab: First Approval. Drugs. 2021, 81, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard M, Laskou F, Stapleton PP, Hadavi S, Dasgupta B. Tocilizumab (Actemra). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017, 13, 1972–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, LJ. Tocilizumab: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs. 2017, 77, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of Tocilizumab in Giant-Cell Arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers EC, Eschenauer GA, Troost JP, et al. Tocilizumab for Treatment of Mechanically Ventilated Patients With COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 73, e445–e454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hernández FJ, González-León R, Castillo-Palma MJ, Ocaña-Medina C, Sánchez-Román J. Tocilizumab for treating refractory haemolytic anaemia in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012, 10, 1918–1919. [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis A, Sacco E, Celani C, et al. Tocilizumab for massive refractory pleural effusion in an adolescent with systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021, 19, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoyi M, Shrestha B, Hui L, Qiujin D, Ping F. Tocilizumab therapy for persistent high-grade fever in systemic lupus erythematosus: two cases and a literature review. J Int Med Res. 2022, 50, 3000605221088558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüptner M, Zeuner R, Schreiber S, Laudes M, Schröder JO. Successful application of belimumab in two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus experiencing a flare during tocilizumab treatment. Lupus. 2014, 23, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, HA. Secukinumab: A Review in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Drugs. 2019, 79, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, HA. Secukinumab: A Review in Psoriatic Arthritis. Drugs. 2021, 81, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan HF, Ye DQ, Li XP. Type 17 T-helper cells might be a promising therapeutic target for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008, 4, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh Y, Nakano K, Yoshinari H, et al. A case of refractory lupus nephritis complicated by psoriasis vulgaris that was controlled with secukinumab. Lupus. 2018, 27, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrić M, Radić M. Is Th17-Targeted Therapy Effective in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus? Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023, 45, 4331–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang F, Sun L, Wang S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib, Baricitinib, and Upadacitinib for Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020, 95, 1404–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan K, Huang G, Sang X, Xu A. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2019, 393, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, et al. 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019, 78, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).