1. Introduction

Emerging in 2008 as an important buffer to climate change, nature-based solutions (NbS) have been gaining increasing global recognition as a promising tool to tackle various societal challenges while providing human well-being benefits [

1,

2,

3]. In order to bring out the potential of NbS in creating environmental, social, and economic benefits, scholars and practitioners are actively exploring contributing elements to successful implementation, among which indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) is highlighted. Under the context of NbS, ILK can also be referred to as “traditional knowledge (TK)” [

4,

5], “traditional ecological knowledge (TEK)” [

6], and “indigenous environmental knowledge (IEK)” [

7]. It covers indigenous beliefs, practices, cultures, philosophies, and everyday lifestyles which lay their roots in local ecosystems and are developed through a long history of co-existence and reciprocity with nature [

5,

7,

8,

9].

ILK can contribute to context-based NbS which enables adaptive management and increases social justice. First, a site-specific design that combines local environmental and cultural contexts is desired for successful implementation of NbS [

10]. To achieve such a design, various evidence including science and TK from local people need to be collected and analyzed when developing NbS [

11]. Second, due to the uncertainties of dynamic nature and the shifting socio-political landscape, the long-term effectiveness of NbS requires adaptive management with timely modification and regular monitoring [

1,

12,

13,

14]. ILK can be an impactful tool in this aspect. International reports and academic studies have shown that indigenous people provide a source of knowledge for climate adaptation, biodiversity conservation, urban and rural resilience enhancement, and disaster control [

3,

15]. For instance, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report stated with high confidence that planning processes that integrated ILK and scientific knowledge could effectively prevent maladaptation and control consequent risks to marginalized and vulnerable groups [

16]. Another example is the sustainable forest management methods developed by indigenous groups in the Indian Himalayan Region which contributed to biodiversity conservation under changing scenarios of the unique local ecosystem [

5]. Third, omissions of ILK in decision-making and the exclusion of indigenous communities in implementation could threaten the social justice in NbS [

7,

17]. By validating, integrating, and protecting ILK, NbS projects can prevent potential biopiracy and uplift indigenous groups when pursuing environmental, social, and economic benefits [

18].

In China while NbS are gaining increasing significance, there is a research gap regarding the inclusion of ILK. First, policies and practices falling within the concept umbrella in China are scattered, and current research on NbS in China is at an early stage of sorting out a policy framework or obtaining case-specific insights under certain issues [

19,

20]. Additionally, a discrepancy in defining and applying the term “indigenous and local communities” between international and domestic political contexts also creates obstacles to systematically investigating the function of ILK in Chinese NbS projects. In 1995, China abandoned the term “indigenous”, considering the fact that the marginalization of indigenous groups by European colonization was not domestically applicable [

21]. The official rejection of the international concept has made it challenging for international scholars and practitioners to understand the real indigeneity in China. For example, by investigating activities conducted by international environmental non-governmental organizations in China, Hathaway concluded that while international projects actively connect with local people, they tend to simply substitute “indigenous people” with “ethnic minority groups”, and insufficient insights of the local context has constrained benefit delivery for marginalized communities [

22].

In fact, as NbS receive attention in China, the providers of ILK mentioned in NbS policies go far beyond minor ethnicity. So far, China has been actively promoting NbS as a mainstream climate action for international cooperation and a core principle for nationwide restorations of the mountain, river, forest, farmland, lake, and grassland ecosystems [

23,

24]. Even though scholars have identified that ethnic minority communities in China are conceptually aligned with the term “indigenous and local communities” in international agreements such as the Convention of Biological Diversity and Nagoya Protocol by providing traditional resources and knowledge [

25], the status quo in terms of recognizing indigenous knowledge in NbS design and implementation in China is more diverse. In addition to integrating and preserving traditional knowledge of ethnic minorities in the National Biodiversity Conservation Priority Projects from 2011 to 2030, policies by the Chinese central government also mentioned other vital sources of ILK [

26]. One typical case is the combination of conventional and modern agriculture and the preservation of traditional rural cultures in rural revitalization and rural sustainable development plans [

27,

28]. Furthermore, a broader community such as citizens and grassroots people is encouraged to participate and contribute their knowledge and skills to ecological protection and restoration plans in the northern sand protection belt, southern hilly mountains, and northeastern forests from 2021 to 2035 [

29,

30,

31].

Therefore, this paper aims to summarize the actual progress of ILK in NbS policies in China and analyzes innovative practical cases. First of all, this study systematically collects policy data and conducts a policy analysis to increase the understanding of ILK integration in NbS of international scholars despite scattered policies and an absence of certain jargon in China. By presenting pathways of impact by ILK on NbS from policy perspectives and exemplar case studies, lessons learned are provided for practitioners to achieve the potential of ILK in China and in the meantime make potential contributions to utilizing and expanding ILK in NbS at a global scale.

2. Conceptual Approach and Methodology

2.1. ILK Integration Framework

So far, studies have pointed out various ways for ILK to contribute to successful NbS. They can be found in both documents and practices from international to local levels. While specific methods generated to bring out the potential of ILK need to be tailored to different environmental, social, and economic contexts, there are four common channels across different situations. The first is preservation and protection of traditional knowledge, which has been underlined in not only international agreements such as the 1992 Convention on Biodiversity Diversity (CBD) but also national policies like the climate initiatives in Canada [

18,

32,

33]. The second pathway is to adopt ILK and engage the target group in decision-making throughout the design, implementation, and management processes with thorough consideration, respect, and necessary combination with technical approaches [

17,

34,

35]. As the third aspect, supervision emphasizes an ILK-led monitor pattern which enhances the adaptability and resilience of NbS [

1,

36]. Last, but not least, a general participation of indigenous people and local communities is also considered critical for just NbS, the scope of which covers the aforementioned three aspects as well as extra possible descriptions including community co-creation, full participation, and co-production [

11,

14,

15].

Major pathways of ILK integration highlighted in domestic context as shown in

Table 1 are similar to international ones, despite minor differences. The National Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Biological Species Resources of China released in 2007 precisely defined the traditional knowledge:

Knowledge, experience, innovation, or practice of current or potential values which have been accumulated and developed by local residents or communities within certain areas over a long period of time and passed on from generation to generation.[37](Translated by authors)

This policy responded to the initiative of conserving, utilizing, and sharing indigenous and traditional knowledge of biological species and genetic resources proposed in the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD). This policy echoed the two pathways of preservation and adoption in international literature. Specifically, action plan from 2006 to 2020 was presented, the core of which was to preserve, utilize, and pass on the expertise of ethnic minority groups regarding traditional medicine, genetic resources, traditional cultivation and breeding techniques, and conventional cultures, arts, and beliefs.

Participation and supervision can also be found in Chinese policies though there is no direct mention of ILK. They are often mentioned together as enabling conditions for successful policy implementation, usually in the last section, but detailed guidance and requirements on these two pathways can also be found in the main body of certain policies. A typical case here is the river and lake chief system where a multi-layer monitoring system from central to village-level government is outlined for effective and long-term water basin management [

38].

One dimension that is not obviously underlined in the discussion around ILK in the international context but particularly emphasized in Chinese policies as another enabling condition is education. Within the domestic political discourse, it refers to the distribution of knowledge and skills, where ILK can be incorporated, among citizens in order to develop a society-wide learning and action-taking environment. This pathway has been included in the ILK integration framework because it not only encourages community participation, which may cover indigenous groups, but also creates a positive atmosphere to build up social recognition of and mutual trust in appropriate knowledge and understandings including ILK.

2.2. Policy Data Collection and Analysis

First, this study identifies policies that proposed the same method and concept under the NbS definition by IUCN (

Table 2). The search scope is all publicly available policies at the national level excluding laws on the official websites of the State Council, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR), The Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs (MARA), the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MoHURD), the Ministry of Water Resources (MWR). Limited to the national level in the review process, this study excludes provincial and municipal policies to make the domestic mainstream idea clear and the research feasible.

Second, this study narrows NbS policies down to those mentioning ILK based on two groups of keywords. The first group includes “indigenous” and its synonyms under the international discourse, including “traditional” and “local”. Concepts with a wider scope which cover indigenous groups as a subset are also counted in, including “community members”, “villagers”, “citizens”, “grassroots”, and “residents”. The second group indicates knowledge, including “experience”, “understanding”, “comment”, “suggestions”, “skills”, “cultures”, “strategies”. Policies are considered relevant for our review only if they mention one or more keywords from each of the two groups respectively.

The two steps above gather 116 policies from July 1985 to February 2023 in total. Based on the selected policies, this study first identifies major sources of ILK by categorizing policies based on terms describing characteristics of a certain group and counting policies mentioning corresponding groups. Second, the overall trend of five pathways by the number of policies with mentions over the studying period is presented. Contributors to the dynamics and noticeable time nodes over time are also analyzed. The general trend is followed by a closer look at the percentage of each pathway, its main providers of ILK, and common societal challenges under which the pathway is exercised.

2.3. Exemplar Case Selection and Analysis

In addition to policy analysis, this study conducts an in-depth analysis on typical cases to examine constructive elements of ILK as well as which and how the pathways are realized in a real situation. With selected cases, the study also identifies lessons for successful ILK integration in China and potential gaps between policies and practices. Innovative practices on ILK integration were selected based on five criteria: (1) the selection focuses on three major application fields of Chinese ILK policies including biodiversity, rural development, and water management, which are identified through methods in the following section; (2) the practice has gained domestic or international recognition for its ILK incorporation with awards or inclusion in typical case study books so as to provide propagable lessons; (3) indigenous people as a critical source of ILK, the core of this research, are clearly identified and demonstrate multidimensional participation; (4) the project has lasted for over five years and is continuously strengthening its capability of creating sustainable impacts and being scaled up at a larger scale in order to offer invaluable lessons on long-lasting benefit delivery; and (5) the project is planned and operated based on coordination among various stakeholders from the government to the civil society, which enables the study to analyze the impact of policies on practices as well as potential implementation gap.

Based on the five criteria above, three typical cases were selected, including Qiandao Lake Water Fund, the protection network for Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, and Laohegou Land Trust Reserve. This study focuses on three aspects of these cases: (1) how ILK is integrated through one or more of the five dimensions from a practical perspective; (2) how relevant policies influence these procedures; and (3) innovative highlights and limitations of ILK integration. Data were collected from two sources. The authors gathered initial background information of the cases through academic publications and online media coverage. Key facts and implementational details were then confirmed through semi-structured interviews with project practitioners who are involved or once involved in corresponding projects for over five years with a good knowledge of government and community coordination. The interview questions are included in the Supplementary Material.

3. Policy Analysis Results

3.1. Indigenous Groups Identification

In terms of sources of ILK, this study categorizes six target groups mentioned in policies based on their definition scopes (

Table 3). The first two are clearly defined by official documents, including ethnic minority groups and low-income people. The former is defined as the 55 ethnic groups other than the Han people [

39]. The latter can be defined as people whose income is 0.75 times or less of the median of urban incomes according to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics. Before 2020, the year marking the completion of national poverty alleviation drive, this group also covers the needy, namely the population living under the national poverty line [

40]. Additionally, this study also sorts out three subgroups of the general concept of local people. The first group features keywords including “grassroots”, “indigenous”, and “within the project area”. The second group appears in policies with specific geographic areas, including villagers in rural areas, fishermen for marine management, and herdsmen within grasslands. The third group considers locally-sourced and community-based positions such as river chiefs and lake chiefs. Finally, a wider society that covers but does not specifically pinpoint indigenous and local people is also included in this framework in case a general adoption of ILK is missing during this analysis. It should be notified that terms are not completely independent from one another, and there can be partial overlaps between groups. For example, the overlap between the low-income group and rural residents is the target beneficiary under the national rural revitalization plan.

A distinguishing feature of indigenous groups in China is the wide coverage. The quantitative analysis, as shown in the

Table 3, showcases that people in a general concept are considered as the carrier of knowledge, which forms the top keynote of policies on NbS. Specifically, the broader community group ranks the top by the number of total mentions. Typical qualitative descriptions include consulting strategies from the people as a primary implementation principle for the policy, and catering to the concerns and demands of people as a guiding ideology, and community engagement as an enabling condition [

41,

42,

43].

The identifications of indigenous groups in Chinese NbS relevant policies are different from the international policy research. Studies on ILK integration in NbS in countries or regions other than China has attached significance to marginalization and vulnerability closely associated with historical reasons, ethnicity, and climate change [

6,

7,

16,

32]. By comparison, groups included in Chinese policies are found along with descriptions on environmental, economic, and social status quo, including income levels, jobs and functions, geographic administrative borders, and ecological borders. Despite less straight-forward reference to vulnerability, various empowering approaches have been provided with the categorizing framework to consider the disadvantaged groups in an inclusive manner. This is demonstrated as protecting legal rights, providing financial and non-financial rewards for the group contributed to project design, implementation, and management [

44,

45,

46].

3.2. Overall Trends of ILK Integration

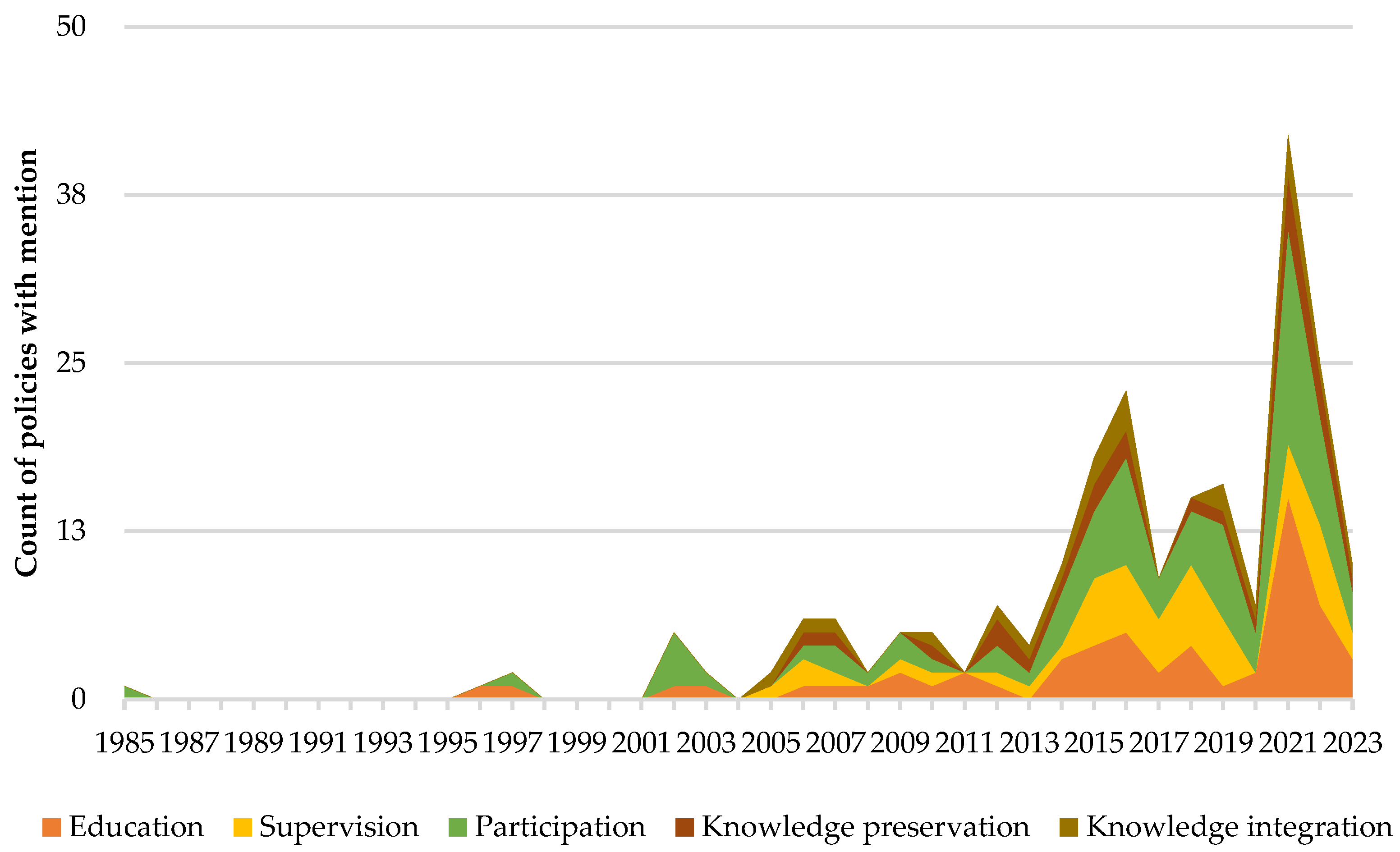

This study indicates an overall increasing trend in the total mention of five pathways since 2010 (

Figure 1), though few mentions of ILK integration before 2000 can be partially attributed to data limitations. As the central Chinese government releases its national development strategic plan every five years, two peaks, in 2016 and 2021, formed due to the intense release of the 13th and the 14th Five Year Plan with detailed guidance on various topics from the General Office of the State Council and ministries.

As suggested by the rising trend in

Figure 1, China has been placing an increasing emphasis on ILK integration in NbS. Specifically, there was a noticeable increase after 2013. It was mainly driven by the creation and expansion of ecological civilization, the core value of which was putting people first, respecting nature, and enabling human-nature harmonious development. The detailed guidance on accelerating the implementation of ecological civilization released in 2015 by the State Council further contextualized and made concrete the principle of “putting people first” in spatial planning, nature conservation, law system development, and society-wide action [

47]. Additionally, the set of carbon peak and carbon neutral goals in 2020 as well as chairing the UN Biodiversity Conference held in Montreal in 2022 also significantly contributed to the increase from the 13th to the 14th five-year plan period.

3.3. Pathways to ILK Integration

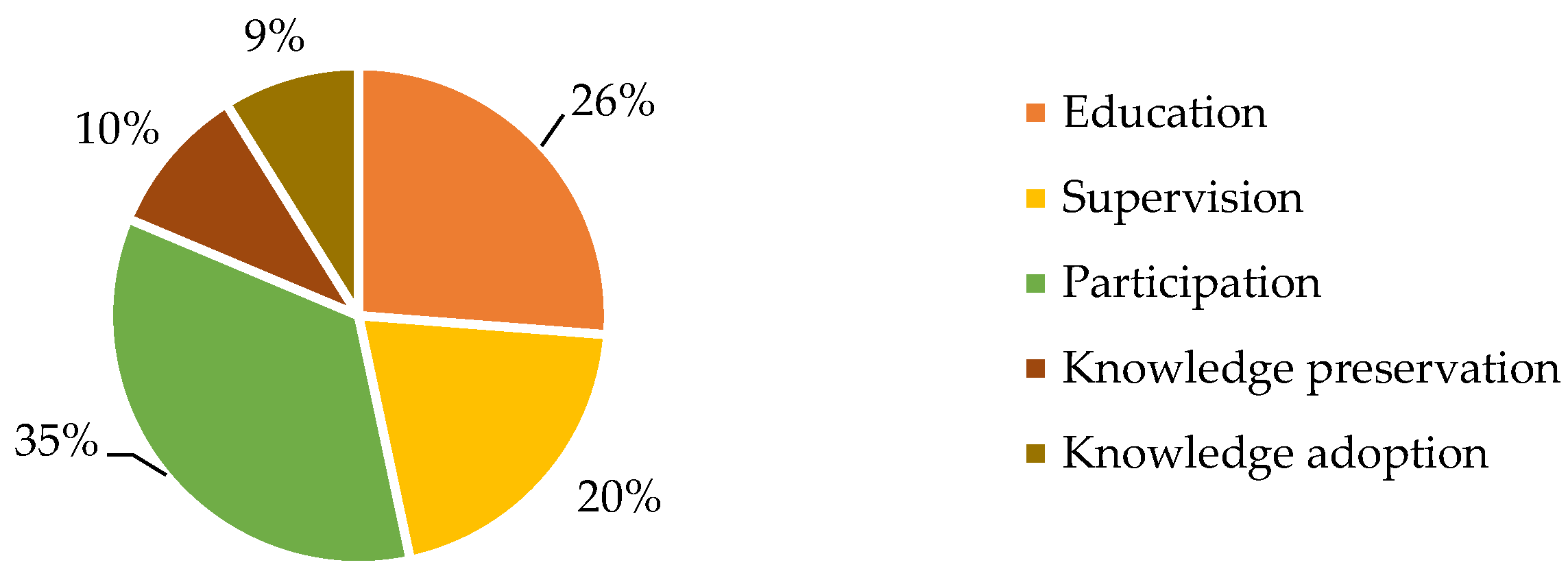

Among 255 mentions in total, participation accounts for the majority, followed by education and supervision (

Figure 2). The high frequency of these three pathways is attributed to their role in the policy document, usually as a principle for implementation in the beginning or an enabling condition at the end. Specifically, the idea of community engagement is often included in the principal section, and enlarging the education scope and ensuring the information accessibility of the wider community for public supervision are outlined following the main body. A relatively smaller proportion of explicit mentions of ILK indicates a potential for extending context-based interpretation to policies intended for different societal challenges.

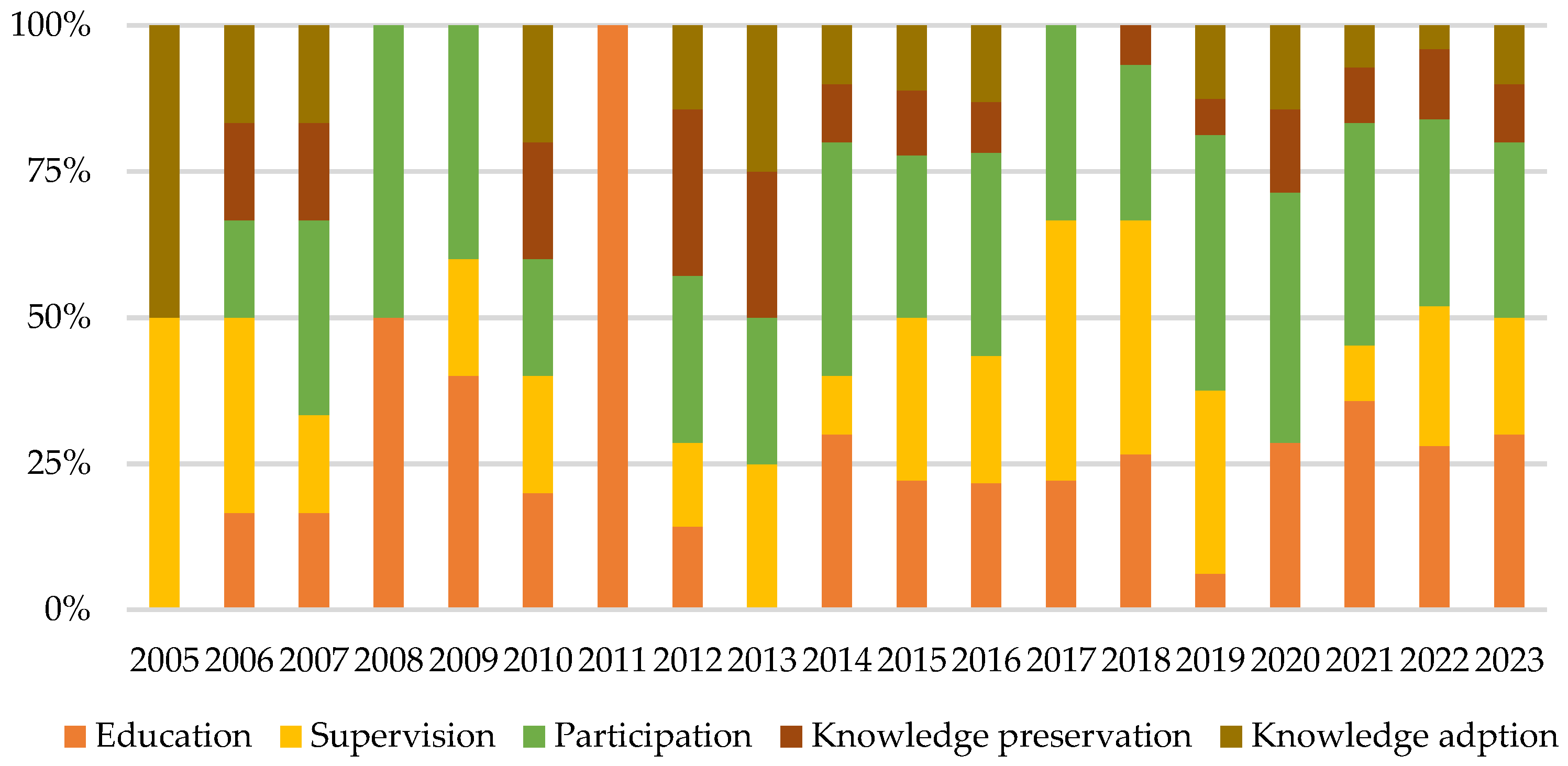

By analyzing the percentage of each pathway since ILK integration started to be mentioned in policies continuously, namely the year of 2015, it could be further seen from

Figure 3 that participation has been taking a leading place consistently, while knowledge preservation and adoption gained notice over the past two five-year plans. The composition of these three pathways has also been enriched over time.

In terms of participation, local people and community engagement get clearly incorporated into the evaluation progress of policy implementation. For example, the Code for Assessment of Nature Reserve Management published in 2017 allocated certain proportion of scores on integrating residents regarding job providing, rewarding, and economic development [

48]. Another progress is the elaboration on the vague concept of multi-participation, which has been extended to enterprises, social organizations, individuals, schools and so on with clear operation patterns such as franchising, financing, voluntary work, and course delivery [

49,

50,

51].

For knowledge preservation and adoption, the initiative of rural revitalization in the 14th Five Year Plan largely contributed to their boost. It is established on the foundation of placing rural people such as farmers, villagers, herdsmen, and fishermen at the core, and promoting full-scale development of rural industries, talents, cultures, ecology, and organizations [

52]. The integration of ILK in these five pillars has been further elaborated in policies released by ministries accordingly. One common focus of these policies is the conservation and passing on of rural history, traditional skills, and culture. The economic and social values of ILK are highlighted, since they tend to be linked with the inheritance of cultural heritage, architecture protection and renovation, tourism, and development of side industries [

27,

53,

54,

55].

3.4. Major Groups and Application Fields under Five Pathways

By counting policies mentioning the five ILK integration pathways, this study identifies the top three main fields and target groups under each pathway (

Table 4). The fundamental idea of relevant policies – people carry knowledge and skills which should be valued and integrated in NbS – applies to all situations. This is demonstrated by the fact that the wider society has the highest number of mentions under each of the five pathways.

With a closer look at major fields, biodiversity, water management, and rural development are the top three issues among all fields with 29, 26, and 24 relevant policies respectively. It could be discovered that Biodiversity and Rural development have gained attention especially under the two pathways giving a direct reference to knowledge. Contributors to the popularity of biodiversity conservation include precise definition of ILK created in central policies, a close link with CBD initiatives, and context-based goals and action plan for different biodiversity conservation priority projects. Rural development is supported by a diversified range of associated industries in the rural area, multidimensional roles of rural communities in NbS implementation, and consistent respect to rural traditional cultures and heritages.

Major groups under each pathway are generally consistent with the findings in section 3.1. Regarded as carriers of knowledge, actors in project implementation and supervision, and the target of education, the broader community rank the top regarding policy mentions in all pathways. Groups with more detailed characteristics (group A and B) are mentioned less in central policies, allowing the flexibility and possibility for lower-level government to narrow down the scope based on local contexts.

4. Typical NbS Cases Study in China

4.1. Case Background

4.1.1. Qiandao Lake Water Fund

Located in Chun’an County, Zhejiang Province, Qiandao Lake is a critical source of drinking water in East Coast China especially for Hangzhou metro area [

56]. However, the lake was faced with the risk of eutrophication due to agricultural non-point source pollution [

57]. In order to restore water quality and tackle unsustainable farming, Qiandao Lake Water Fund was officially launched in 2018 with joint efforts from the government, the World Bank, The Nature Conservancy, Minsheng Insurance Foundation, Alibaba Foundation, and Wanxiang Trust after three years of investigation and preparation. Since then, pilot nature-based agricultural solutions, including ecological ditches, constructed wetlands, green fertilizer covers, and nectar plants, have been introduced to local croplands and economic products farmlands. So far, the pilot practices have been proved effective with 30%-40% nitrogen and phosphorus loss reduction with co-benefits in decreasing carbon emissions and increasing community income [

57].

Qiandao Lake Water Fund is an innovative and ground-breaking exploration of long-term water source protection pattern in China for prospective NbS upscaling and with multi-stakeholder participative governance as a core. The systematic restoration of ecosystems in Qiandao Lake was listed in Typical NbS Cases in China published by IUCN and the Ministry of Natural Resources [

58]. Additionally, the environmental, social, and economic benefits achieved by Qiandao Lake Water Fund at the current stage for local communities and its potential of replicability are well recognized by the Food and Agriculture Organization in the case collection “Nature-based solutions in agriculture: the case and pathway for adoption”[

59].

In this project, three groups of local communities are identified and included: rural dwellers in Chun’an County, the river chief team which is partially constituted by residents in Chun’an County, and citizens in Chun’an County and those living in downstream areas. ILK is mainly derived from the first two groups, while the focus of the third group education to foster a social environment in which people widely understand and participate. In particular, the two groups are included as key decision makers in this project since they generate direct impact on the water quality while being directly influenced by the outcome of NbS implementation. Additionally, their familiarity with local soil, water, and species has great potential to facilitate indigenous land and river management, planting methods, and invasive species identification.

4.1.2. Yunnan Snub-nosed Monkey Protection Network

Living in Yunnan and Tibet, the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey was included as endangered in the red list of threatened species by IUCN in 2003 and categorized under first class protection animals in China [

60]. One of the key drivers of its habitat loss is human disturbance including logging, agriculture, and grazing [

61]. While collaboration between the government and civil society over the past 40 years has increased the total number through establishment of nature reserves, its vulnerability remains high due to the habitat fragmentation and a small group size [

62]. In order to enhance the overall habitat connectivity and boost community sustainable livelihoods, the Yunnan Forestry and Grassland Administration initiated the protection network for Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys in 2019 with 13 organizations including governmental departments, academic institutions, and non-governmental organizations based on the pilot protection project launched in 2014. The scientific expert team has been closely cooperating with local communities in identifying priority areas, planning ecological corridors, and conducting vegetation restoration with indigenous plants. So far, the network has restored connected habitats of over 11,000 mu, which enabled carbon sequestration of 432,000 tons and a noticeable increase in community income in the meantime [

63,

64].

The protection network was recognized as an exemplar pattern of participative biodiversity governance and ecosystem restoration by the Ministry of Natural Resource of China in the case collection of “Typical case of ecological restoration in China” for it bring out the potential of NbS in benefiting local environment, society, and economic development [

63]. Moreover, this case provides invaluable experience of tackling the challenge of low community participation by establishing community-based protected areas. ILK is mainly obtained from villagers living within and near the protection network, among which the majority are ethnic minority groups such as the Lisu, Tibetan, Bai, Naxi, and Yi people. The case incorporates diversified ILK including traditional knowledge of landscapes and species, indigenous languages, as well as cultures and religions.

4.1.3. Laohegou Land Trust Reserve

The Laohegou area is located within four critical potential habitats of the giant panda in Pingwu County, Sichuan Province and is included as one of the 32 biodiversity priority areas listed in China Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan (2011-2030) [

65]. Despite the strategic significance of biodiversity, the Laohegou area was confronted with illegal fishing, poaching, and trading of endangered animals including giant pandas. As a response to conservation challenges, the protection project was launched in 2011 and introduced the land trust reserve model in 2013 after the Government of Pingwu County transferred the land-use right to civic organizations. The reserve introduced financial support from the private sector and integrated knowledge from local residents and forest farm rangers in protected area establishment, regular patrols, reduction of human interventions in protected areas, key ecosystem restoration, and development of community-based sustainable industries. As of 2022, the reserve has achieved a cumulative patrol coverage of more than 5,000 miles, expanded effective protection from 110 square kilometers to nearly 250 square kilometers, and increased the wildlife encounter rate.

Laohegou Land Trust Reserve is the first protected area of public welfare managed by civic organizations in China [

65]. The progress of this ground-breaking model provided invaluable lessons for societal participation in nature reserve management. The outstanding project design and management also won it the 2016 British Expertise International Award. Two main sources of ILK are rangers of the state-owned forest farm and villagers. While villagers who conducted illegal hunting used to be the major threat of endangered species, the project is able to bring out the positive side of ecological knowledge from hunters by organizing community-based patrols. It also upscales the economic values of traditional farming and livestock breeding skills by launching customized agriculture.

4.2. Case Analysis of ILK Integration

4.2.1. Practices and Lessons from the Three NbS Cases in China

The three typical cases showcase rich content, application contexts of ILK, and invaluable lessons in delivering long-term environmental, social, and economic co-benefits by integrating ILK (

Table 5). First, the cases demonstrate that various elements could fall within the concept of ILK, including ecosystem literacy, good practice in farming and breeding, as well as culture and religions. In Qiandao Lake Water Fund, informal knowledge of local soil, species, and water are obtained from rural residents and river chiefs contribute through consultation with villagers, experience sharing sessions, and river patrols conducted by local communities. In the case of protection network, the scientific team can learn from villagers of their in-depth understanding of local landscapes and animal activities by establishing partnerships with those willing to join in protection and restoration activities. Moreover, by living as neighbors over years, the scientific team is able to increase familiarity with lifestyles, cultures, and religious beliefs of ethnic minority groups, which carries wisdom of co-existence with nature and ethnographic values but has been declining nowadays. At Laohegou Land Trust Reserve, the information-sharing sessions for protection animal identification allow local forest farm rangers to freely share their knowledge of forest ecosystem dynamics and up-to-date living status of various species. Additionally, traditional practices of livestock breeding and ideas, observant habits of key animals, and ideas of land management can be learned in the Meetings of Villagers, where governmental officials, residents within and around the protected area, and the scientific team are gathered together for joint decision-making.

Five pathways of ILK integration are realized in a context-based manner in three cases. Application situations here include educational programs targeting a wider community, strategy design and implementation for ecological protection, restoration, and adaptative management, and community development based on value realization of ecological products. While two or more application situations can be found in each case, the three cases are featured with different contexts. Specifically, Qiandao Lake Water Fund has greatly boosted its impact on downstream residents by inviting river chiefs to interactive education programs. For example, in April 2021, the Water Fund organized an event “I have a fish in Qiandao Lake” with the aim of increasing the awareness of saving water and the knowledge of nature-based water protection of companies and citizens from downstream cities. During this event, river chiefs from Chun’an County presented their knowledge of habit types of fish in the lake as well as experience in water management such as cleaning invasive species and telling water quality by observing indicator fishes. The vivid narration of community-based water protection stories motivated on-site participation and contributed to an event page view of over 306,000 online within one month. In the protection network, traditional ecological literacy is integrated as part of the protection and restoration planning and implementation. A typical example here is that at the initial stage of the project, the scientific team were confused by the complicated mountainous landscapes and easily got lost when conducting ecosystem research and searching key habitats. Therefore, local villagers were invited as team guides to trace and follow snub-nosed monkeys effectively, identify critical ecological corridors, and find ways efficiently in the wilderness. ILK integration in Laohegou Land Trust Reserve is particularly highlighted in community economic development. Built upon the improved environment within nature reserves, the scientific team helped local villagers develop customized eco-friendly agricultural products, where indigenous farming and livestock breeding techniques were fully adopted. This ensures product quality and increases motivation of community participation, resulting in the successful selling of the first batch with attractive profits and increased community partnership in the following several batches.

A mutual lesson learned from the cases is that to generate long-lasting multidimensional values, it is essential to enable participation from indigenous people and local community since initial planning and gradually enlarge the scale and scope through trials and errors. Throughout three cases, dependence on ILK started at early stages including key species identification, ecological restoration methods development, and conservation practice design. Taking the case of Qiandao Lake Water Fund as an example, when designing nature-based solutions for controlling the use of chemical herbicide in the first batch of tea garden, the scientific team would not have been able to figure out appropriate vegetation covers compatible with soil conditions and tea growth without consulting farmers about localized vegetation. The integration of ILK is expected to be upscaled to enable wide-reaching co-benefits. In the case of Laohegou Land Trust Reserve, the customized products started with a small group of villagers and later extended over twentyfold by exploring and keeping suitable producing techniques while abandoning improper ones. In this way, economic values can be created in pace with conservation achievements.

4.2.2. Comparison with International Practices

The cases show a highly consistent essence of the ILK concept with that in international studies, namely the co-existence and reciprocity with nature. This is signified by traditional water and fish management practices to perform effective river patrols, indigenous animal tracking skills complementary to modern technology in ecological corridor mapping, and context-specific understanding of forest ecosystem dynamics. More importantly, through five pathways and three application situations, invaluable ILK is able to regain its significance among indigenous people and local communities and transform unsustainable behavior, eventually contributing to a synergy between environmental protection and economic development. Bright examples here are the protection network for Yunnan snub-nosed monkey and Laohegou Land Trust Reserve. The community members used to belittle endangered animals. However, as they realize that their experience and knowledge can contribute to protection activities and improve livelihoods, they feel proud of an increased wildlife encounter rate and become even more motivated as participators.

Similar to the role of ILK in NbS implementation in international studies, three cases also highlight ILK in adaptative management through community-led supervision activities shown in

Table 5. Moreover, although it is not obvious in studies in the international context, incorporation of ILK in impact-generating activities gains significance in Qiandao Lake Water Fund and Laohegou Land Trust Reserve. In addition to “I have a fish in Qiandao Lake”, Laohegou project has trained and employed a group of local villagers to become tour guide for external visitors into protected areas. In this way, villagers are encouraged to enrich ecological education to a wider community with their personal know-how and stories in restoration and protection. However, dedicated methods to ILK preservation such as establishment of institutions, protocols, and knowledge database outlined in international studies and Chinese central policies are not evident in the three cases selected [

18].

4.3. The Role of Policies, Implementation Highlights, and Limitations

The three cases demonstrate the foundational idea in ILK relevant policies – people in a general concept are considered as the carrier of value knowledge and skills – by enabling contribution from a wide range of community members on multiple occasions. This is not only attributed to the guiding principles of community participation in national and provincial policies as shown in

Table 6, but also due to the innovation of three cases. The authors were informed through the interviews that each of the three cases distinguishes itself from conventional practices in its corresponding field for wide stakeholder inclusion and community leadership. Therefore, the cases suggest that even though there might be a gap regarding implementing the core idea of central and provincial policies in water management, biodiversity conservation, and rural development, several feasible and promising patterns for effective ILK integration have been discovered through innovative explorations.

While high-level policies provide guiding opinions, realizing such a general idea highly relies on endorsement, mobilization of residents, and internal operational consistency by local governments. First, formal or informal permission of multi-stakeholder protection and restoration in the case of Water Fund and protection network and official transfer of land-use right to civil organizations in Laohegou provide the precondition for any community-based pilot activities. Second, by virtue of its well-established reputation and reliability, the local government plays a critical role in motivating indigenous people and local communities to join the projects especially at early stages by enhancing their confidence and solving potential concerns. Personnel mobilization coordinated by the government resulted in successful formation of the river chief team in Qiandao Lake and the ecological corridor patrol team in the protection network. Third, consensus among different governmental departments at a local level is desired before outreaching to a wider community. In the case of Laohegou Land Trust Reserve, no mutual decision-making mechanism could come into force until the functional inconsistency between two committees under the village government was fixed. More importantly, while governments across different levels play irreplaceable roles in setting implementation principles and guidelines as well as enabling community engagement, one-size-fits-all policies could fail to bring out the potential of ILK. Instead, the cases showcase that it is important for higher-level authorities to allow flexibility to local governments as well as non-governmental bodies in making context-based operational plans and make timely adjustment.

5. Conclusions

One key element of effective NbS is ILK integration. While the word “indigenous” is not recognized officially in China, policies developed by Chinese central government include a wide range of sources of ILK, from people with specific social and economic characteristics, local residents, to a broader community. By conducting a systematic policy review, this study discovered that people are widely considered as a source of knowledge in NbS-related policies. In general, there has been a noticeably increasing emphasis on ILK integration over the past two five-year-plan periods, which can be mainly attributed to the ecological civilization construction, the establishment of carbon peak and carbon neutral goals, and the role as the host at the UN Biodiversity Conference. Specifically, through education, supervision, participation, knowledge preservation, and knowledge adoption, ILK is expected to facilitate the co-benefit generation by NbS in biodiversity conservation, rural development, water management, and other application fields.

From a practical perspective, three exemplar cases have shown promising exploration and innovation in ILK integration by distinguishing themselves from conventional practices in multi-stakeholder participation and leadership of local communities. At a practical level, ILK is constituted by diversified elements, including ecological literacy, good producing practices, and local custom and five pathways are realized in a contextualized manner. A consistent emphasis on co-existence and reciprocity with nature as well as the role of ILK in adaptative management is found in both international studies and domestic cases. The cases also demonstrate successful ILK incorporation in educational activities to raise community awareness.

The policy review and case studies in this paper provide lessons on upscaling ILK integration in NbS at a larger scale. First, the people centered principle first and community participation should remain at the core of policies and projects to set the scene for ILK identification and integration. Second, it is significant that wide-reaching ideas in policies allow practical flexibility in the field, since ILK can be highly context-specific and thus requires tailored local institutions to bring out the best of it. Additionally, as suggested by the cases, successful ILK integration relies not only on overall guidance from the central government, but also highly on the resource mobilization and endorsement of local authorities, without which civil society organizations or local communities might not be able to achieve viable pathways or expected benefits of ILK integration.

Due to a limited number of cases, this study falls short of insights in ILK preservation through dedicated approaches. Furthermore, while typical cases imply a potential gap of ILK integration between policies and conventional practices, this study does not cover any mainstream but traditional projects and cannot draw a solid conclusion on where and why the gap exists as well as potential solutions. Future studies could expand the scope of case study to explore a more comprehensive understanding of the role of ILK in NbS implementation in China by delving into the knowledge preservation and adoption methods in both mainstream and ground-breaking practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Interview questions are available upon request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Y. and Q.M.; methodology, R.Y. and Q.M.; validation, R.Y. and Q.M.; formal analysis, R.Y.; investigation, R.Y.; resources, R.Y. and Q.M.; data curation, R.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Y.; writing—review and editing, R.Y. and Q.M.; visualization, R.Y.; supervision, Q.M.; project administration, Q.M.; funding acquisition, Q.M.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China on the Life Style of Urban Residents in Green and Low-carbon Society, grant number 22ASH012. This research was also supported by China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED) Special Policy Study (2021-2022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed for the policy review section in this study. This data can be found on the websites of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR), The Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs (MARA), the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MoHURD), the Ministry of Water Resources (MWR). The policy screening result and case interview notes are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Wei Kang and Haohong Liao for participating in case study interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Semi-structured interview outline is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. IUCN. IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions: First Edition.

- UN Environment Programme. UN Environment Assembly Concludes with 14 Resolutions to Curb Pollution, Protect and Restore Nature Worldwide Available online:. Available online: http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/un-environment-assembly-concludes-14-resolutions-curb-pollution (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- World Bank. Biodiversity, Climate Change, and Adaptation: Nature-Based Solutions from the World Bank Portfolio; World Bank: Washington, DC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Negi, V.S.; Pathak, R.; Thakur, S.; Joshi, R.K.; Bhatt, I.D.; Rawal, R.S. Scoping the Need of Mainstreaming Indigenous Knowledge for Sustainable Use of Bioresources in the Indian Himalayan Region. Environ. Manage. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, N.; Nakamura, H.; Hamzah, A. Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key? Sustainability 2020, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z.J.; Wijsman, K.; Tomateo, C.; McPhearson, T. How Deep Does Justice Go? Addressing Ecological, Indigenous, and Infrastructural Justice through Nature-Based Solutions in New York City. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 138, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska, K.; Argumedo, A.; Song, Y.; Rastogi, A.; Gurung, N.; Wekesa, C.; Li, G. K: Knowledge and Values, 2021.

- Watson, J.; Robertson, A.; Rosen, F.D. DESIGNING BY RADICAL INDIGENISM. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Andrade, A.; Dalton, J.; Dudley, N.; Jones, M.; Kumar, C.; Maginnis, S.; Maynard, S.; Nelson, C.R.; Renaud, F.G.; et al. Core Principles for Successfully Implementing and Upscaling Nature-Based Solutions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 98, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, H.; Balian, E.; Azevedo, M.; Beumer, V.; Brodin, T.; Claudet, J.; Fady, B.; Grube, M.; Keune, H.; Lamarque, P.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe. Gaia Okologische Perspekt. Nat.- Geistes- Wirtsch. 2015, 24, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.P.; Guiomar, N. Nature-Based Solutions: The Need to Increase the Knowledge on Their Potentialities and Limits. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1925–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, B.; Yumagulova, L.; McBean, G.; Charles Norris, K.A. Indigenous-Led Nature-Based Solutions for the Climate Crisis: Insights from Canada. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiddle, G.L.; Bakineti, T.; Latai-Niusulu, A.; Missack, W.; Pedersen Zari, M.; Kiddle, R.; Chanse, V.; Blaschke, P.; Loubser, D. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Climate Change Adaptation and Wellbeing: Evidence and Opportunities From Kiribati, Samoa, and Vanuatu. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (Eds.)].; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 3056. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, G.; Brunet, N.D.; McGregor, D.; Scurr, C.; Sadik, T.; Lavigne, J.; Longboat, S. Toward Indigenous Visions of Nature-Based Solutions: An Exploration into Canadian Federal Climate Policy. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, C. Avoiding a New Era in Biopiracy: Including Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 135, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Gu, B.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhai, H. Advances, Problems and Strategies of Policy for Nature-Based Solutions in the Fields of Climate Change in China. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 17, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Sun, Y.; Rong, Y.; Hu, J. NbS practice in landscape engineering in Lishui city. China Land 2022, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.C. Pathways of “Indigenous Knowledge” in Yunnan, China. Alternatives 2007, 32, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, M.J. China’s Indigenous Peoples? How Global Environmentalism Unintentionally Smuggled the Notion of Indigeneity into China. Humanities 2016, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. New Zealand-China Leaders’ Statement on Climate Change Available online:. Available online: https://english.mee.gov.cn/News_service/news_release/201904/t20190401_698078.shtml (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China; Ministry of Fiance of China; Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. Shanshui Lintian Hucao Shengtai Baohu Xiufu Gongcheng Zhinan (Shixing) [Project Guide for Ecological Protection and Restoration of Mountains, Rivers, Forests, Farmlands, Lakes, and Grasslands (for Trial Implementation)] Available online:. Available online: https://www.cgs.gov.cn/tzgg/tzgg/202009/W020200921635208145062.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Li, B.; Xue, D. Applicability and evaluation index system of the term “indigenous and local communities” of the Convention on Biological Diversity in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2021, 29, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Guanyu Yinfa Zhongguo Shengwu Duoyangxing Baohu Zhanlue Yu Xingdong Jihua (2011-2030 Nian) [Notice on the Issuance of China’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan (2011-2030)] Available online:. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bwj/201009/t20100921_194841.htm (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. Quanguo Nongye Kechixu Fazhan Guihua (2015-2030 Nian) [National Plan for Sustainable Agricultural Development (2015-2030) Available online:. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/qnhnzc/201505/t20150528_4622065.htm (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. “Shisiwu” Xiangcun Lvhua Meihua Xingdong Fang’an [The 14th Five-Year Plan of Action for Rural Greening and Beautifying] Available online:. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20221027153039525170128 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Beifang Fangshadai Shengtai Baohu He Xiufu Zhongda Gongcheng Jianshe Guihua (2021-2035 Nian) [Plan for the Construction of Major Ecological Protection and Restoration Projects in the Northern Sand Prevention Zone (2021-2035)] Available online:. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20220110163633586987237 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Nanfang Qiuling Shandidai Shengtai Baohu He Xiufu Zhongda Gongcheng Jianshe Guihua (2021-2035 Nian) [Plan for the Construction of Major Ecological Protection and Restoration Projects in the Hilly and Mountainous Regions of Southern China (2021-2035)] Available online:. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20220112104223124547639 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Dongbei Senlindai Shengtai Baohu He Xiufu Zhongda Gongcheng Jianshe Guihua (2021-2035 Nian) [Construction Plan of Major Ecological Protection and Restoration Projects in Northeast Forest Belt (2021-2035)] Available online:. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20220112104459162711942 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Townsend, J.; Moola, F.; Craig, M.-K. Indigenous Peoples Are Critical to the Success of Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change. FACETS 2020, 5, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 33. United Nations. Convention on Biological Diversity, 1992.

- Gupta, M.C.; Gupta, S. Strengthening Community-Led Development of Adaptive Pathways to Rural Resilient Infrastructure in Asia and the Pacific. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2023, 8, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.; Freeman, M.; Freeman, B.; Parry-Husbands, H. Reshaping Forest Management in Australia to Provide Nature-Based Solutions to Global Challenges. Aust. For. 2021, 84, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sacco, A.; Hardwick, K.A.; Blakesley, D.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Breman, E.; Cecilio Rebola, L.; Chomba, S.; Dixon, K.; Elliott, S.; Ruyonga, G.; et al. Ten Golden Rules for Reforestation to Optimize Carbon Sequestration, Biodiversity Recovery and Livelihood Benefits. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1328–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Quanguo Shengwu Wuzhong Ziyuan Baohu Yu Liyong Guihua Gangyao [The National Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Biological Species Resources] Available online:. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/zj/wj/200910/t20091022_172479.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Ministry of Water Resources. Guanyu Jinyibu Qianghua Hezhang Huzhang Lvzhijinze de Zhidaoyijian [Guidelines on Further Strengthening the Duties of River and Lake Chiefs] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-01/01/content_5465754.htm (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- State Council Information Office of China. Zhongguo de Shaoshuminzu Zhengce Ji Qi Shijian [China’s Minority Policy and Its Practice] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2005-05/26/content_1131.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Cox, S. Poverty Eradication: A Chinese Success Story Available online:. Available online: http://za.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/sgxw/202210/t20221019_10785796.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Ministry of Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China. Guanyu Yinfa Shisiwu Quanguo Chengshi Jichusheshi Jianshe Guihua de Tongzhi [Notice on the Issuance of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Urban Infrastructure Construction] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-07/31/content_5703690.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Water Resources. Guanyu Jiakuai Tuijin Shengtai Qingjie Xiaoliuyu Jianshe de Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines on Speeding up the Construction of Ecologically Clean Small Watershed] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/15/content_5741554.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Quanguo Shidi Baohu Guihua (2022 - 2030 Nian) [National Wetland Protection Plan (2022-2030)] Available online:. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/sites/main/main/gov/content.jsp?TID=20230104172037356945593 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Land and Resources. Guanyu Jiaqiang Kuangshan Dizhi Huanjing Xiufu He Zonghe Zhili de Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines on Strengthening Restoration and Comprehensive Treatment of Geological Environment in Mines] Available online:. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/gwy/201611/t20161124_368161.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Tianranlin Baohu Xiufu Zhidu Fang’an [Systematic Plan for Natural Forest Protection and Restoration] Available online:. Available online: http://f.mnr.gov.cn/201907/t20190725_2449134.html (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Jianli Yi Guojiagongyuan Wei Zhuti de Ziranbaohudi Tixi de Zhidao Yijian [A Guideline on Establishing a System of Protected Natural Areas with National Parks as the Main Body] Available online:. Available online: http://f.mnr.gov.cn/201906/t20190627_2442400.html (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Jiakuai Tuijin Shengtai Wenming Jianshe de Yijian [Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of Ecological Civilization] Available online:. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/qnhnzc/201505/t20150506_4581636.htm (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Ziran Baohuqu Guanli Pinggu Guifan [Code for Assessment of Nature Reserve Management] Available online:. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bgg/201712/t20171229_428892.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Guojiaji Haiyang Baohuqu Guifanhua Jianshe Yu Guanli Zhinan [Guidelines for Standardized Construction and Management of National Marine Reserve].

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Guojia Gongyuan Kongjian Buju Fang’an [National Park Spatial Layout Scheme] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/30/content_5734221.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Guli He Zhichi Shehui Ziben Canyu Shengtai Baohu Xiufu de Yijian [Opinions on Encouraging and Supporting the Participation of Social Capital in Ecological Protection and Restoration] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-11/10/content_5650075.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Quanmian Tuijin Xiangcun Zhenxing Jiakuai Nongye Nongcun Xiandaihua de Yijian [Opinions on Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization and Accelerating Agricultural and Rural Modernization] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-02/21/content_5588098.htm (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Guanyu Cujin Xiangcun Lvyou Kechixu Fazhan de Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines on Promoting Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2018-12/31/content_5439318.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Xiangcun Zhenxing Zhanlue Guihua (2018-2022 Nian) [Strategic Plan for Rural Revitalization (2018-2022)] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-09/26/content_5325534.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- State Council Information Office of China. Guanyu Tuidong Chengxiang Jianshe Lvse Fazhan de Yijian [Opinions on Promoting Green Development of Urban and Rural Construction] Available online:. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/21/content_5644083.htm (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Gu, Q.; Li, J.; Deng, J.; Lin, Y.; Ma, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, K.; Hong, Y. Eco-Environmental Vulnerability Assessment for Large Drinking Water Resource: A Case Study of Qiandao Lake Area, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 9, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Mu, Q.; Wang, L.; Guo, F.; Ge, L. Nature-Based Solutions to Water Crisis Practice in China: Eco-Friendly Water Management in Qiandao Lake, Zhejiang Province. Nat. Prot. Areas 2021, 1, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 58. Ministry of Natural Recourses of China; IUCN. Typical Nature-based Solutions Cases in China, 2021.

- Iseman, T.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Nature-Based Solutions in Agriculture: The Case and Pathway for Adoption; FAO and TNC: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003.

- Su, X.; Han, W.; Liu, G. Potential Priority Areas and Protection Network for Yunnan Snub-Nosed Monkey (Rhinopithecus Bieti) in Southwest China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ding, W.; Xiao, W.; Ye, H. New Distribution Records for the Endangered Black-and-White Snub-Nosed Monkeys (Rhinopithecus Bieti) in Yunnan, China. Folia Zool. 2019, 68, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Recourses of China. Protection network for the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey; Zhongguo Shengtai Xiufu Dianxing Anli [Typical case of ecological restoration in China]; Ministry of Natural Recourses of China: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Nature Conservancy. Annual Report on Overall Protection Network for Snub-Nosed Monkey Conservation in Yunnan Available online:. Available online: https://tnc.org.cn/content/details27_948.html (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Jin, T.; Ni, J.; Wang, J. Practice and Experience in the Protection of Public Welfare Protected Areas in Sichuan: An Example from Laohegou Nature Reserve in Pingwu County. In Sichuan Ecological Construction Report (2018); Sichuan Bluebook; Social Sciences Literature Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).