Introduction

Amidst a background of concern, and even a sense of crisis, about the impact of pandemic on higher education, this paper explores student numbers and income in Scottish universities through the Covid-19 pandemic. It focuses on the University of Glasgow, contextualised with comparisons to other Scottish universities. The main findings can be summarised simply: universities in Scotland significantly increased their income during the pandemic, and they did this by substantially expanding international student numbers. International postgraduate students were by far the main driver of income growth, and many higher education institutions (HEIs) in the country substantially increased income from this source during the pandemic relative to their pre-pandemic levels. For example, in just two years (2020/21 and 2021/22) the University of Edinburgh made more than half a billion pounds (£608 million), and the University of Glasgow nearly half a billion pounds (£482 million) from international tuition alone, accounting for the lion’s share of all international tuition income in Scotland (65% of the £1.7 billion total earned by Scottish universities in these two years).1

This paper reviews income as well as changes in student numbers and composition over the past six years, focusing on how the years of pandemic from 2020 to 2022 have differed from pre-pandemic times. It concludes that Covid constituted a unique situation in which widespread worries about loss of income and students were contradicted by an actual pattern of substantial increases in both for Scottish universities. Hence, the frame of crisis through which universities initially viewed the pandemic has since transformed into a frame of opportunity that allowed Scottish universities to expand. Scottish universities of all sizes and kinds, pre- and post-1992, research and teaching intensive, all rapidly grew income from international students, especially in 2021-22. The University of Glasgow has pursued expansion of international student numbers and income more aggressively than most HEIs and key markers of this are presented below.

An analysis of HEI income trends through the pandemic is followed by a section analysing expanding student numbers and the impact of this on the changing composition of student populations in Scottish higher education. I then focus on a specific example of income generation through Kaplan International, a multi-national for-profit operator of pre-degree course prep as well as student housing and other services. Its partnership with the University of Glasgow via the Glasgow International College collects tens of millions of pounds annually from international students and is part of a wider market in which students are circulated to UK universities. In the final part, I draw on recent work analysing staff casualisation in UK universities to illustrate the relation between expanded student numbers and job security, focused on the University of Glasgow, exemplifying the impact of rapid expansion on work conditions.

The paper concludes by considering how the shifting composition of students and emphasis on income growth during the pandemic is re-shaping the higher education landscape in Scotland. It raises a number of concerns, across the Scottish HE sector, flowing from increasing dependence on and pursuit of international student fees. Among these are: the concentration of university financial health (and risk) on a single, unpredictable source; the unequal distribution of this income across universities so that some are generating far more income than others from international students; a fundamental change to the nature of the student experience where larger class sizes are normalised; a concern about housing access for rising numbers of students, and, equally, a concern about the impact of higher student numbers on housing costs for non-university residents; and increasing casualisation of university staff. In addition, and of critical importance given the reckoning many universities are attempting around decolonisation and widening participation, is how aggressive recruitment of those who pay the highest fees because they come from outside the UK, calls into question the role of universities in relation to neo-colonialism and their civic commitments to the places in which they are located.

In presenting this analysis, the paper offers a counter perspective to the narrative being pushed by UK universities and their private sector partners. Most recently, a report published in May 2023 by consultancy London Economics, that was commissioned by Kaplan, Universities UK International and the Higher Education Policy Institute. This report trumpeted the economic benefit of international students, receiving high profile media coverage.2 (The same consultancy was hired to produce a 2021 report for the University of Glasgow, which boosted a similar positive message about the economic impact of this single university.3) The report on international students describes China, Nigeria and India as the ‘most prolific’ ‘senders’ of students to UK universities. This phrasing obscures, and some might suggest mis-frames, the extent to which these students are actively sought by UK universities, which pay millions of pounds each year to recruitment agents and companies to find them potential students.4 Nor do these reports consider the situation and impact for international students themselves of studying in the UK, how they finance their degrees and what difference a UK degree makes to their lives back home. More work should be done to critically evaluate such issues. This paper more narrowly focuses on neglected aspects of the economic story, exploring the impact for universities of their income growth during the pandemic, and how this has further impacted student composition.

Data and Methods

The data used in the analysis is taken from university annual reports and audited accounts, HESA open data, and Companies House filings (in the case of Kaplan International, Glasgow International College and Glasgow University Holdings LLC). All these are public sources of data. In addition, contemporaneous analysis of HESA data by Yusuf Khan (making use of data work and analysis of Marion Lieutaud) is included to contextualise findings among Russell Group institutions.5

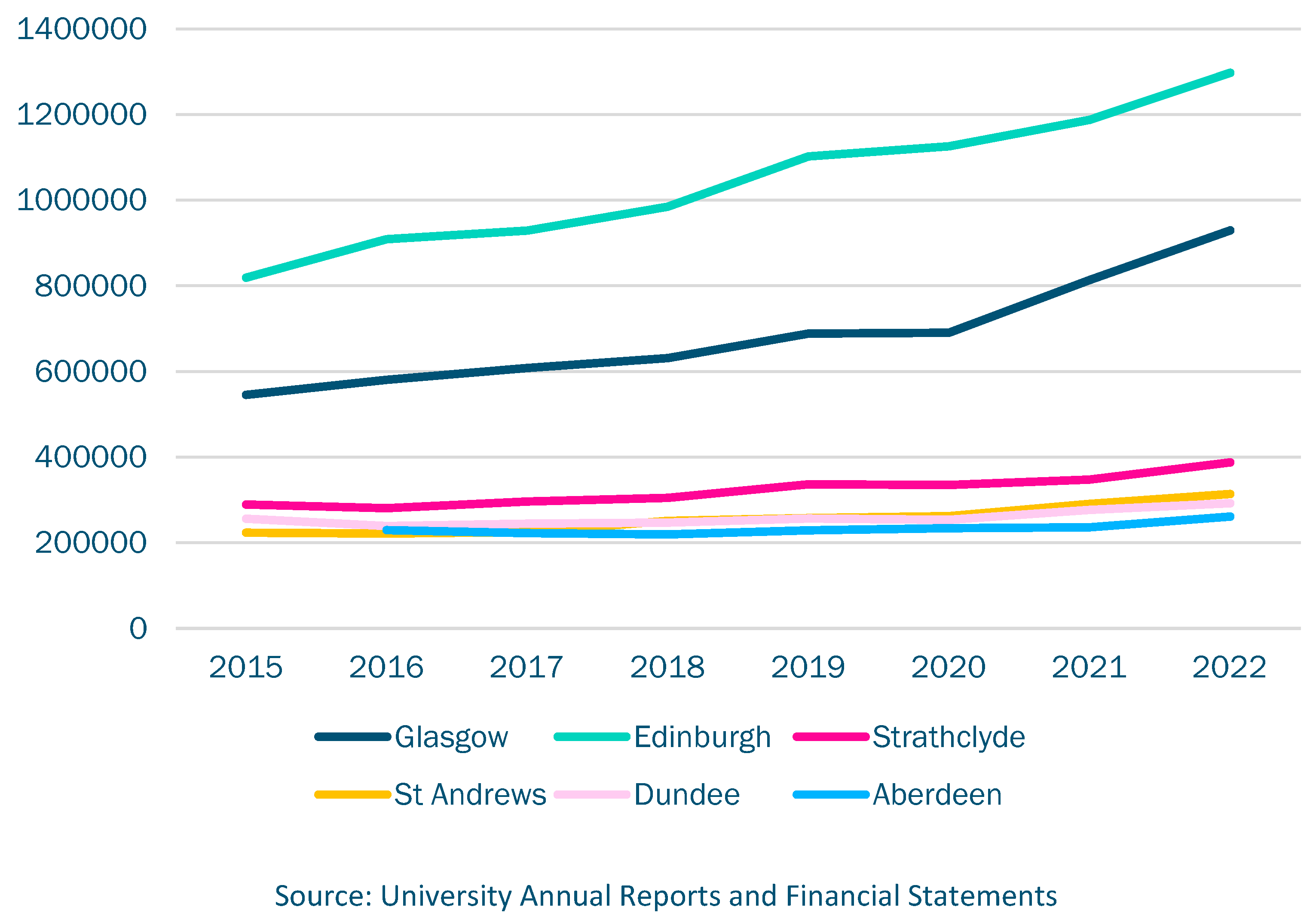

The analysis groups different Scottish universities together at various points. The starting point was to include Scotland’s larger universities. In terms of income, six universities in Scotland turn over more than £250 million per year (2021/22): Edinburgh (£1.3 billion), Glasgow (£929,000), Strathclyde (£388 million), St Andrews (£314 million), Dundee (£292 million) and Aberdeen (£261 million). In terms of numbers of students, Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) and the University of the West of Scotland (UWS) each has more students than St Andrews, Aberdeen or Dundee (with over 20,000 students each).6 The Open University also educates numerous students in Scotland (over 16,000 in 2021/22) but is distinct from other HEIs in having no international students (in its Scottish offshoot) and no physical campus and so is not included. The University of Stirling is similar in income to GCU and UWS, has fewer students but greater research income; it is occasionally included. Smaller (e.g. Abertay) and specialist (Royal Conservatoire, SRUC) institutions are not included due to constraints of time, though it would be valuable and interesting to map patterns across the entire HE sector in Scotland.

Financial analysis of universities tends to focus on their financial health and stability, especially in the short-term from year to year, and thereby to emphasise indicators such as cash flow and reserves.7 The present analysis makes use primarily of income data, as this was the main focus of concern as the Covid-19 pandemic descended.

In May 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic was reaching every part of the world, the European University Association noted: ‘All sources of university income will be affected in some way in the short to medium term.’8 The same briefing concludes: ‘The overall impact of the current crisis will be large and long-lasting, and universities must prepare for operational and financial difficulties in the coming few years.’9 In a sense, this paper takes these statements as a hypothesis, to be tested by looking at the income data we now have through three years of pandemic. The claim at the start of the pandemic was that universities would suffer and that there would be significant impacts of Covid-19 on student numbers and income. This analysis found there were significant impacts but in the opposite direction than that feared.

I. Changes in Scottish university income during Covid-19

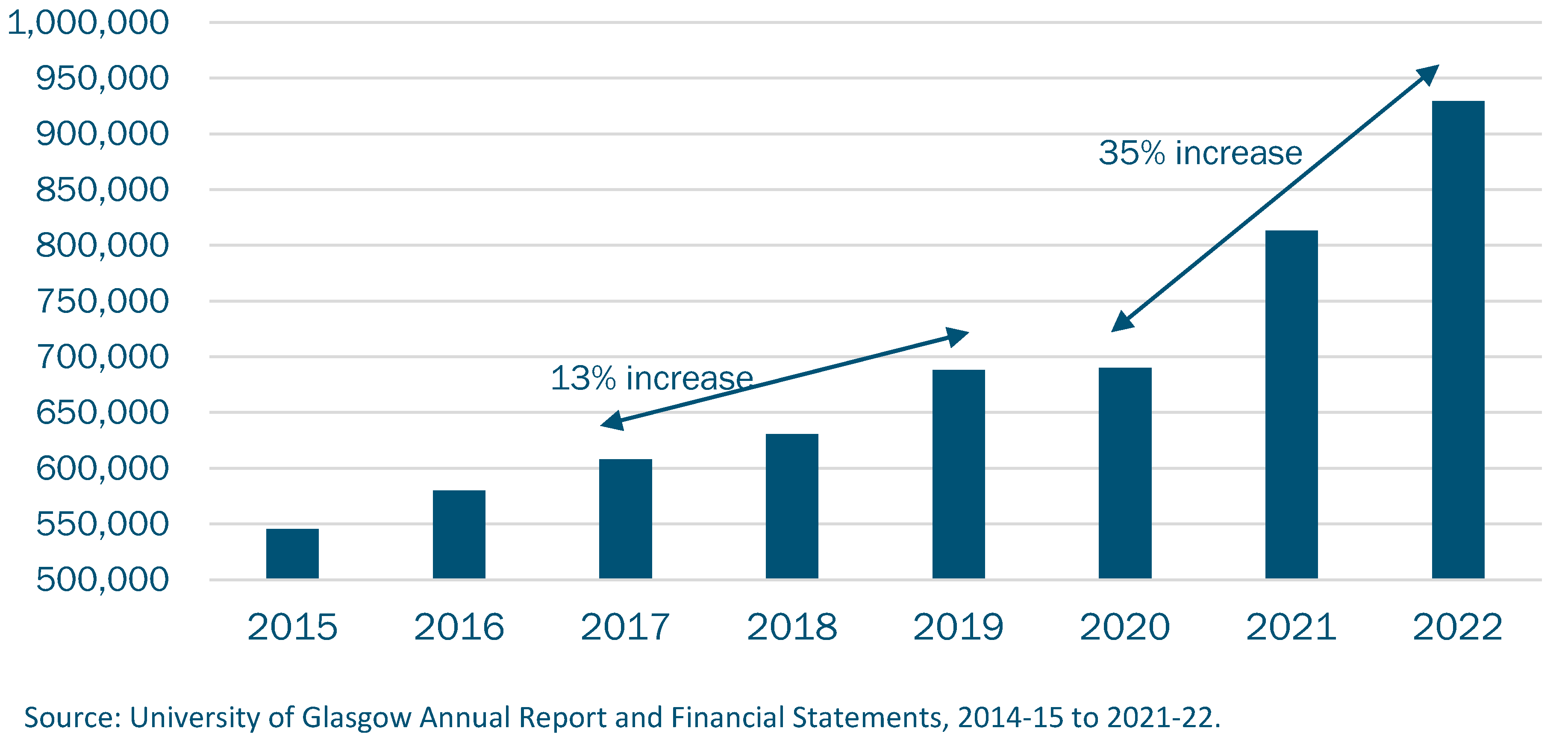

Glasgow University’s rate of income growth stands out among Scottish universities, nearly tripling during the Covid-19 pandemic. The figure below shows a 35% growth rate from 2020 to 2022. In 2022, the university earned £929 million; this is an increase of £241 million on its income in 2019 of £688 million. This works out to the university earning £105 million pounds more than it would have made had its rate of growth during the pandemic remained similar to that during 2017-19.10

Figure 1.

University of Glasgow total income (000), 2015-2022.

Figure 1.

University of Glasgow total income (000), 2015-2022.

The largest universities in Scotland all increased their income during the pandemic, shown in the figure below. The University of Edinburgh, the biggest university by income in Scotland (earning £1.3 billion in 2022), grew its income 15% between 2020 and 2022, an impressive rate though still less than half that of the University of Glasgow.

Figure 2.

Total income (000), larger Scottish Universities.

Figure 2.

Total income (000), larger Scottish Universities.

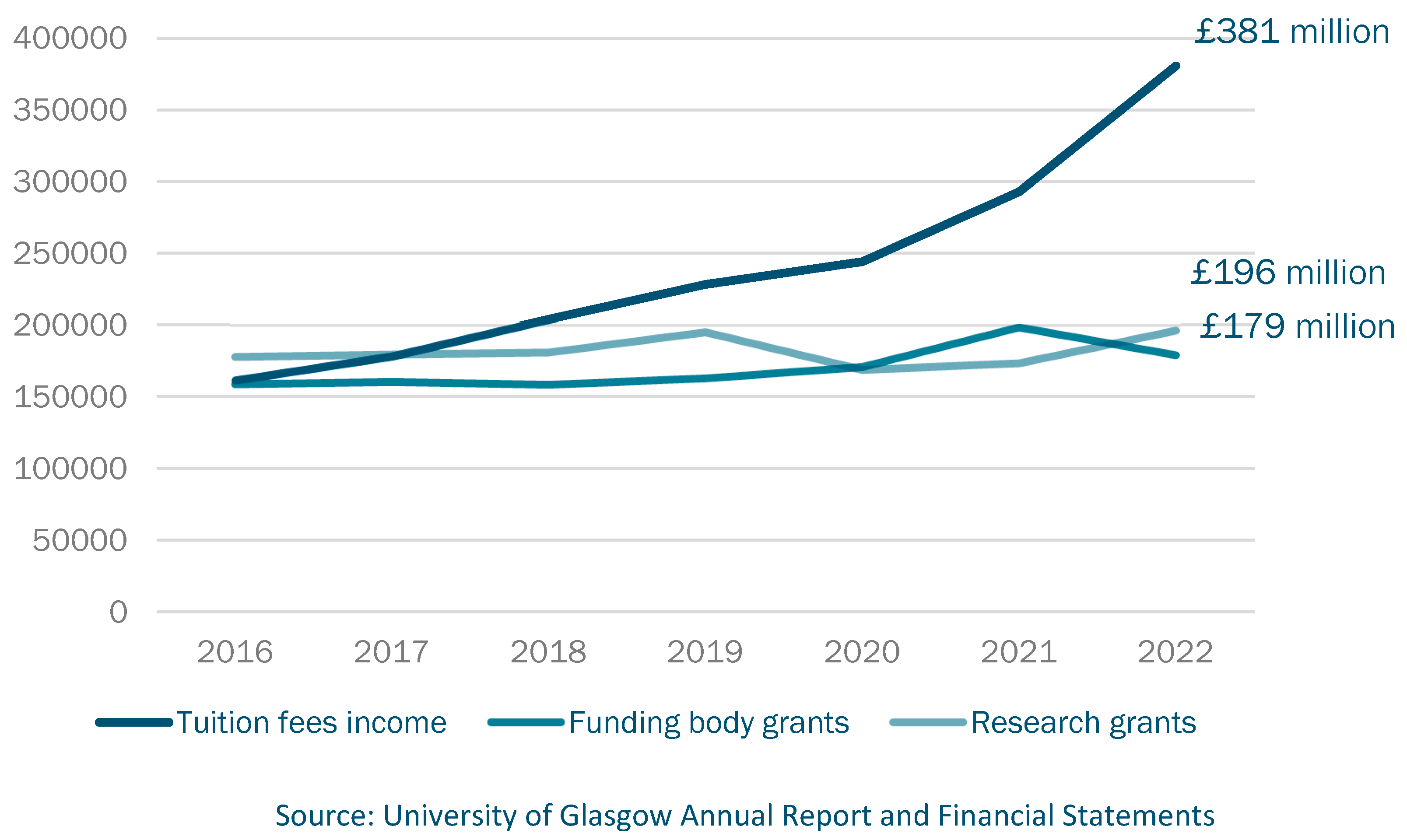

One income source stands out as the main driver of revenue growth – tuition fees. The figure below compares income from the University of Glasgow’s three largest sources of income: funding body grants (e.g. SFC), research and teaching. At the start of the period, the university received as much in income from tuition as it did from funding body grants. This has significantly changed; and while this shift long precedes the pandemic, it has sharply accelerated since 2020. In just six years, tuition has become the most significant source of income to this university.

Figure 3.

University of Glasgow income (000) by source.

Figure 3.

University of Glasgow income (000) by source.

Increased tuition income, in turn, is attributable mainly to one source – non-UK, non-EU based students (referred to throughout as international students11) who pay the highest fees. Tuition alone can range from £22,000 to nearly £50,000 pounds per year, depending on the degree course and level of study.12

The University of Glasgow is not alone in rapidly expanding income from non-EU international students. All of Scotland’s larger universities recruited and admitted more of these students during the pandemic than they had before. As noted, the trend of growth in international student numbers had already been underway before the pandemic, but rates of growth accelerated, in some cases at astonishing levels, during Covid. For example, income in 2022 from international students at UWS was nearly quadruple and at GCU was two and a half times what it had been in 2019, a sharp departure for teaching intensive universities where Scottish students historically comprised around 90% of their student cohorts.13 After these institutions come the Universities of Glasgow (98% rise) and Stirling (96%), which both essentially doubled their income from international student fees during the pandemic.14 Glasgow’s income growth from international fees is more significant than that of GCU and UWS because these latter two were increasing from a relatively low level of income from this source. In 2022, for example, the University of Glasgow earned more than ten times the income from international students than GCU did.

The table below shows income from international tuition at Scotland’s larger universities. Over two years, 2020/21 and 2021/22, the sector made nearly £1.7 billion, and two Scottish Universities earned around half a billion pounds each from international tuition fees – the University of Edinburgh (£608 million) and University of Glasgow (£482 million).15

Table 1.

International tuition income (000) at Scottish Universities 2021 and 2022.

Table 1.

International tuition income (000) at Scottish Universities 2021 and 2022.

| |

2021 |

2022 |

2-year Total |

| Edinburgh |

£272,500 |

£335,500 |

£608,000 |

| Glasgow |

200,300 |

281,500 |

481,800 |

| St Andrews |

79,800 |

89,900 |

169,700 |

| Strathclyde |

42,700 |

58,600 |

101,300 |

| Aberdeen |

42,400 |

57,300 |

99,700 |

| Dundee |

35,800 |

54,600 |

90,400 |

| Stirling |

16,800 |

31,000 |

47,800 |

| UWS |

13,400 |

30,100 |

43,500 |

| GCU |

13,500 |

23,200 |

36,700 |

| Total |

717,400 |

961,700 |

1,679,000 |

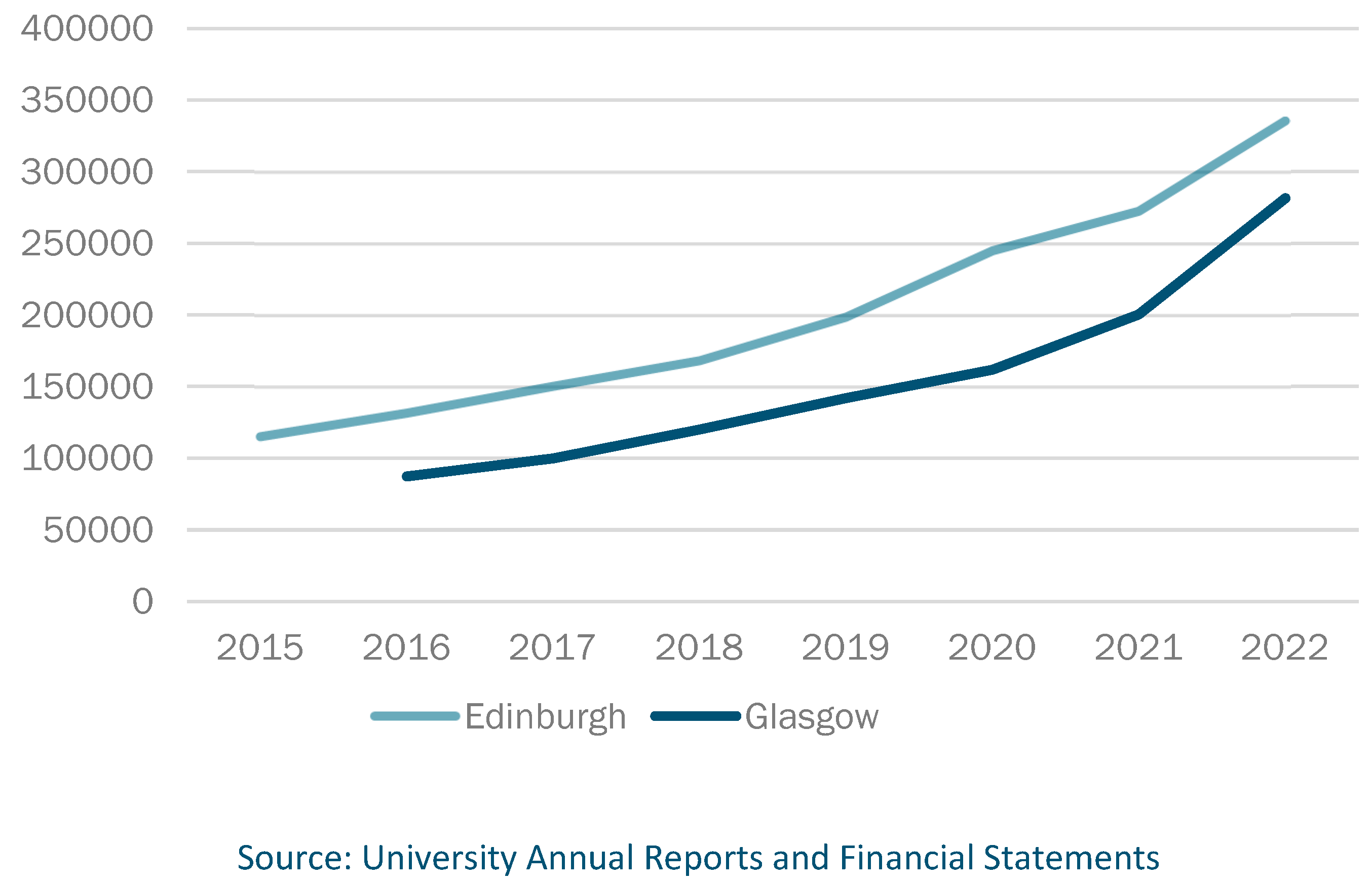

The pattern of international tuition income growth is graphically displayed for Scotland’s two largest university in the figure below. Although Edinburgh made more income from international students (£335.5 million), its growth rate from this source was slower than Glasgow’s, though still considerable, increasing by around 70% between 2019 and 2022.

Figure 4.

International tuition income growth at Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities (000).

Figure 4.

International tuition income growth at Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities (000).

For all the Scottish universities studied, there was an uptick in income especially from 2021. Two universities (Strathclyde and Dundee) that saw international tuition income decline from 2020 to 2021, recovered this growth by 2022.

International student fees have not only grown faster than fees from other categories of students, they also have outpaced growth from other sources of income for almost all Scottish universities (as shown for the University of Glasgow above and shown in the published financial statements of the other universities). This marks a shift towards increasing university dependence on international student fees (and the other revenues connected to this such as accommodation and pre-enrolment course prep programmes, discussed later). While this is a development well-known to university managers, what has been less well known is how universities in Scotland have pursued this source of income with even greater speed during the pandemic, a period which also saw Brexit take an effect, predictably reducing the numbers of EU students in Scottish universities.

The table below shows tuition as share of total income for Scotland’s largest universities. As of 2022, Glasgow University had the highest proportion of income from tuition fees, second only to St Andrews, a university where tuition has historically been a significant source of income. Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee all saw substantial growth in the proportion of their income coming from tuition fees over this six-year period.

Table 2.

Tuition fees as a proportion of total income, selected Scottish Universities.

Table 2.

Tuition fees as a proportion of total income, selected Scottish Universities.

| |

2016 |

2022 |

% Change |

| St Andrews |

39% |

44% |

5% |

| Glasgow |

28% |

41% |

13% |

| Edinburgh |

28% |

38% |

11% |

| Aberdeen |

22% |

34% |

12% |

| Dundee |

20% |

33% |

13% |

| Strathclyde |

29% |

30% |

1% |

The following table shows international tuition income as a proportion of total tuition income for the larger Scottish Universities. It compares this rate from the year before the pandemic (2019) to the current period (2022). International tuition is accounting for a larger share of tuition fee income for all but one Scottish university compared to before the pandemic. The University of Glasgow tops the table in Scotland with nearly three-quarters of all tuition income coming from international students.

Table 3.

International tuition income as a proportion of total tuition income in Scottish universities.

Table 3.

International tuition income as a proportion of total tuition income in Scottish universities.

| |

2019 |

2022 |

% Change |

| Glasgow |

62% |

74% |

12% |

| Edinburgh |

57% |

68% |

10% |

| St Andrews |

64% |

65% |

2% |

| Aberdeen |

51% |

64% |

13% |

| Dundee |

46% |

57% |

11% |

| Stirling |

41% |

50% |

9% |

| UWS |

26% |

46% |

20% |

| Strathclyde |

43% |

41% |

-2% |

| GCU |

24% |

39% |

15% |

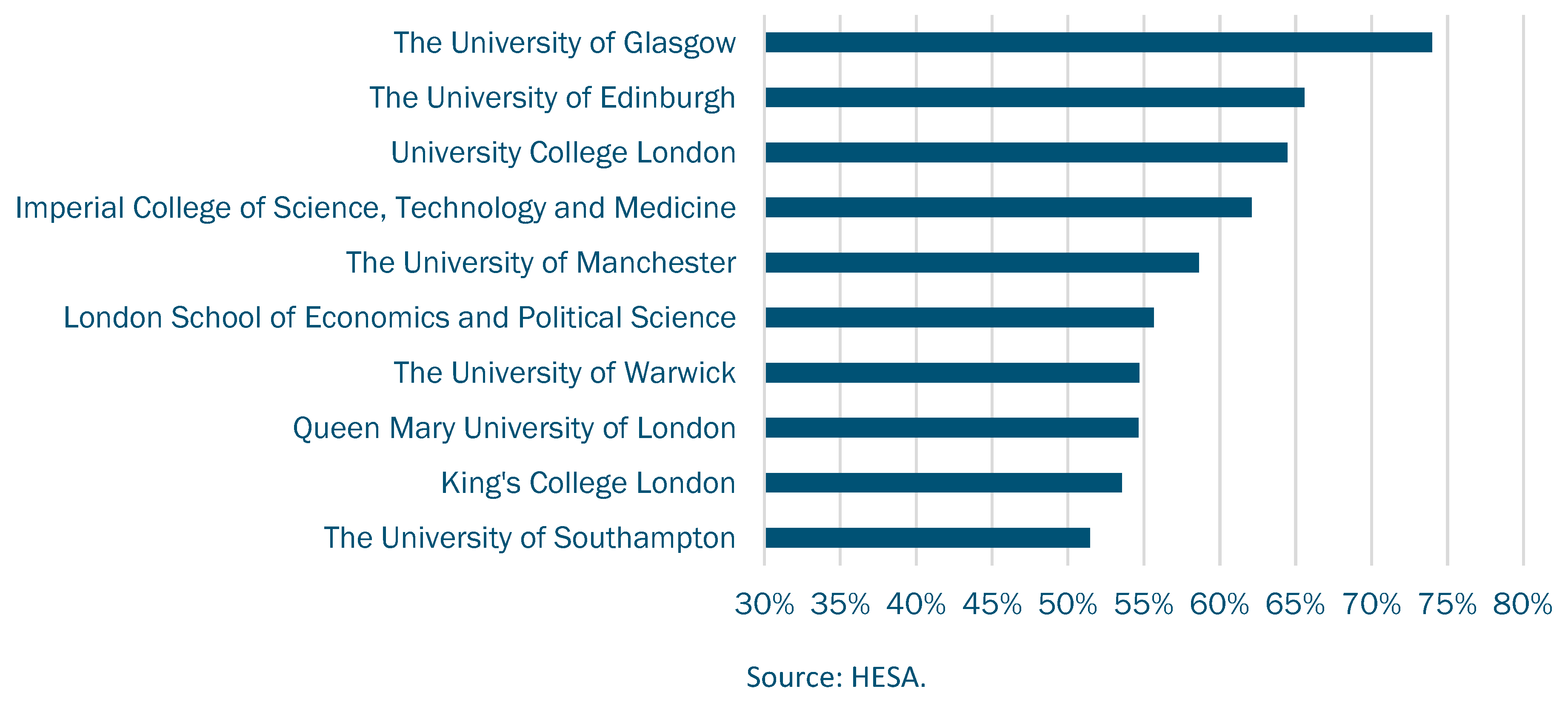

The University of Glasgow’s high share of international tuition also stands out in a comparison among Russell Group (RG) universities. The figure below takes the ten RG institutions with the highest proportion of international tuition income in 2021/22, showing two Scottish universities, Glasgow followed by Edinburgh, to be more reliant on international student income than any other Russell Group institution.

Figure 7.

Percentage of tuition coming from international students in 2021/22 among Russell Group institutions.

Figure 7.

Percentage of tuition coming from international students in 2021/22 among Russell Group institutions.

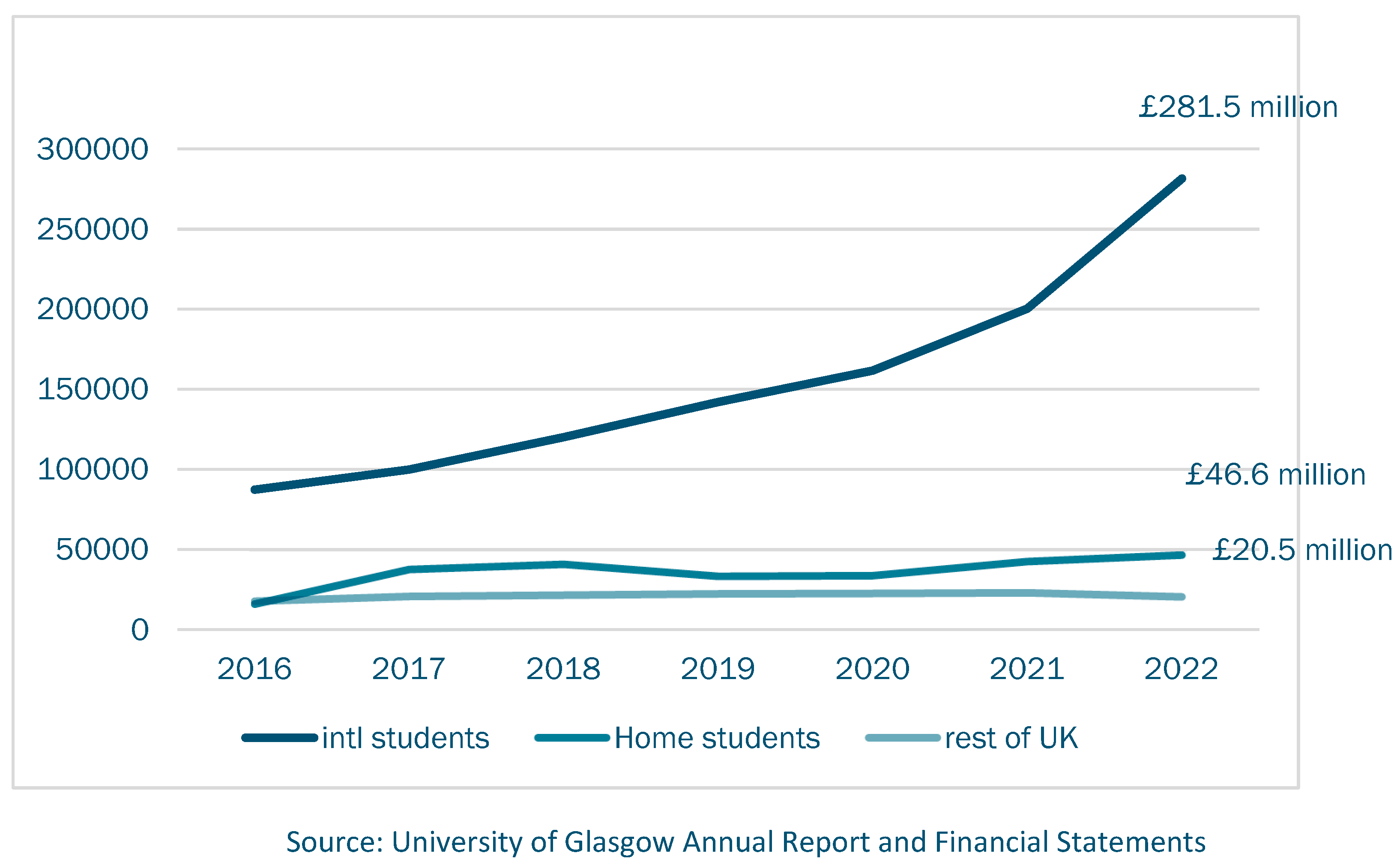

One potential factor in Scottish universities’ higher reliance on international tuition income is the cap on undergraduate student fees and numbers in Scotland, a function of subsidised university education in this part of the UK; in contrast, in England, universities can charge UK students many thousands of pounds more for tuition.16 The graph below of University of Glasgow tuition income may provide support for this theory, showing ‘home’ (i.e. Scottish domiciled students) and rest of UK tuition income remaining fairly flat (with a trend of decline for the latter group). International tuition income was worth £281.5 million pounds to the University of Glasgow in 2022, almost three times its value in 2016 and more than six times the value of income from ‘home’ students.

Figure 8.

Glasgow University Tuition Income (000) by domicile17.

Figure 8.

Glasgow University Tuition Income (000) by domicile17.

While the issue of heavy dependence on international tuition is fully acknowledged in university management circles, it is often justified as necessary in the face of dire university finances and funding structures.18 However, most Scottish universities are in a position of relative financial health, despite billions of pounds borrowed for various campus redevelopment projects across the country. Of the ten larger Scottish universities touched on in this paper, only two had negative surplus(deficit) to income ratios, when excluding pension adjustments.19

Table 4.

Surplus (deficit) as percentage of income, excluding pension costs, Scottish universities, 2022.

Table 4.

Surplus (deficit) as percentage of income, excluding pension costs, Scottish universities, 2022.

| HE Provider |

Surplus/(deficit) as a % of total income |

| The University of Glasgow |

15.8 |

| The University of Stirling |

12 |

| UWS |

11.3 |

| The University of Edinburgh |

11 |

| The University of St. Andrews |

10.1 |

| GCU |

8 |

| The University of Aberdeen |

2.6 |

| Edinburgh Napier University |

2.3 |

| The University of Dundee |

-1.1 |

| The University of Strathclyde |

-2.1 |

Just as the University of Glasgow increased its income faster than other Scottish universities, it also saw its surplus grow disproportionately as well. Its approximately 16% surplus shown above is nearly triple what its already healthy surplus was before the pandemic in 2018/19 of 6% (gain excluding pension adjustment).

The numbers presented here, show not only that Scottish universities are increasing their reliance on high fee-paying international students, but also have shown they have actively expanded this reliance to pursue income that may be surplus to actual need. Recently the Office for Students, an independent regulator of higher education in England, sent a warning letter to 23 universities there about over reliance on international student fees, particular for students from China.20 However, there is no similar oversight body for Scotland, which as discussed in brief below, has disproportionately a greater number of students from this country.

II. Pandemic changes in student numbers at Scottish Universities

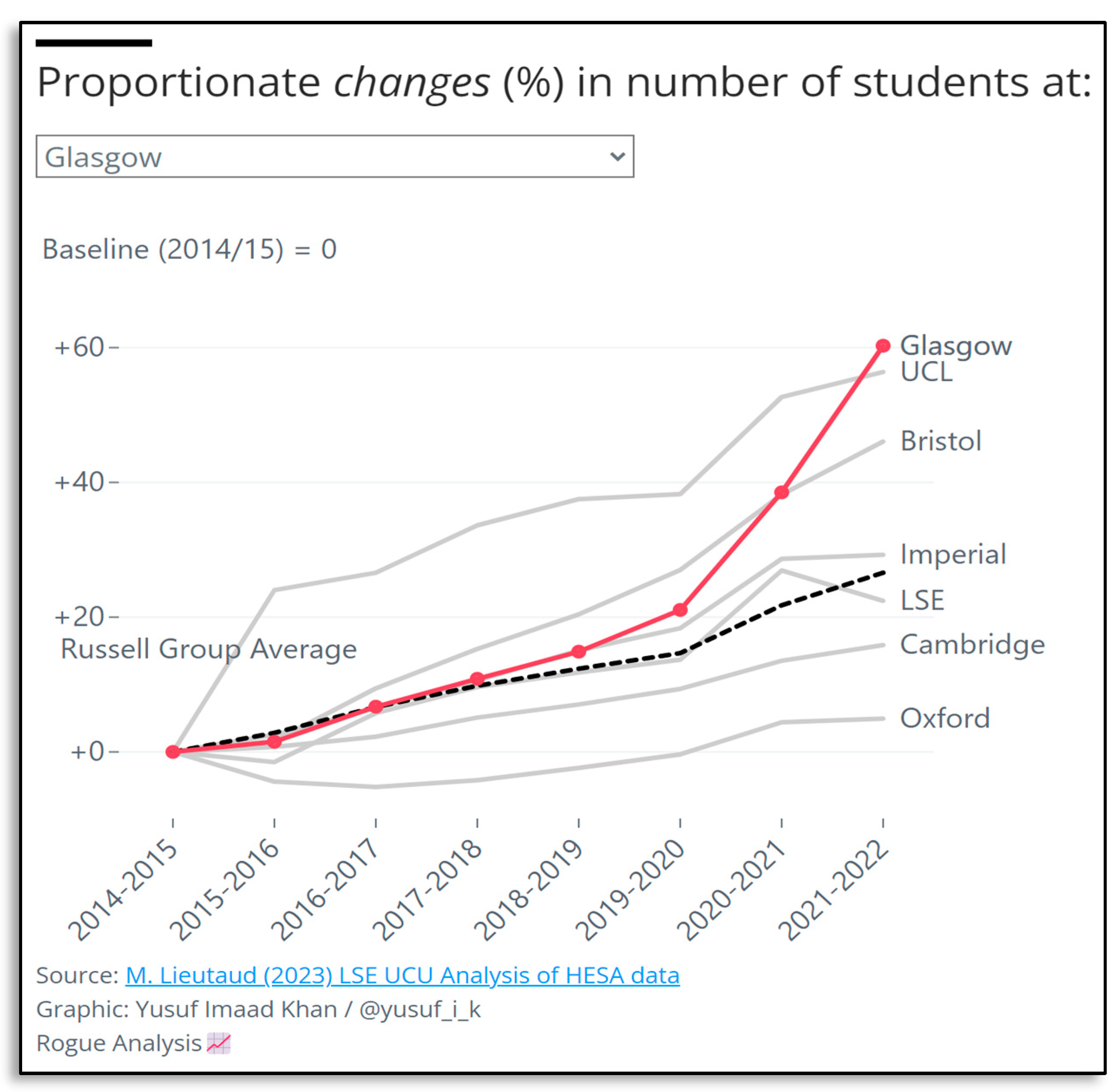

Student numbers in Scotland’s larger universities increased on average by 18% between 2019 and 2022.21 The University of Glasgow experienced the greatest growth in students, increasing these by 40% in just three years, from 31,000 to 43,000 total students.22 This is twice the rate seen at the University of Edinburgh, the next largest university by student numbers; it increased student numbers 20% from 34,000 in 2019 to 41,000 in 2022. The University of Glasgow now has the most students of any university in Scotland and has become the third largest university in the UK, behind only University College London (circa 47,000 students) and the University of Manchester (circa 46,000).23 This is a marked departure from its size only three years ago, when it had 30,800 students and ranked 12th in the UK by student numbers. A recent analysis showed Glasgow’s pace of student expansion was the fastest among Russell Group institutions, shown below, with the pandemic years seeing the most accelerated growth.24

Figure 9.

Russell Group changes in student numbers.

Figure 9.

Russell Group changes in student numbers.

The driver of growth in student numbers, as will be unsurprising in light of the income analysis, is international students. The cap on Scotland-based undergraduate students, for whom the Scottish Government subsidises tuition incentivises income growth strategies focused on international undergraduate and postgraduate students. On average, from 2019 to 2022, the numbers of home (Scotland domiciled) students in Scotland’s larger universities increased by about 10%; the growth in non-EU international students was nearly tenfold greater – a 93% average increase between 2019 and 2022.25 Here again, the University of Glasgow saw higher than average growth, more than doubling its numbers of international students between 2019 and 2022.

Table 5.

International student numbers 2019 and 2022, selected Scottish universities.

Table 5.

International student numbers 2019 and 2022, selected Scottish universities.

| |

18/19 |

21/22 |

%Change |

| UWS |

1,365 |

4,660 |

241% |

| GCU |

1,195 |

2,905 |

143% |

| Glasgow |

6,550 |

14,795 |

126% |

| Dundee |

1,715 |

3,205 |

87% |

| Stirling |

1,730 |

2,945 |

70% |

| Strathclyde |

2,740 |

4,435 |

62% |

| Edinburgh |

9,380 |

14,480 |

54% |

| Aberdeen |

2,335 |

3,170 |

36% |

| St Andrews |

3,745 |

4,440 |

19% |

| Average |

|

|

93% |

Collectively, universities in Greater Glasgow (Glasgow, Strathclyde, GCU, UWS) added almost 27,000 international students to the city in 2021/22. While university-financed consultancy work has highlighted the economic benefits of new residents to cities, negative implications for such things as housing (of both students and non-student residents of Glasgow), teaching space and staff workloads have not been considered.26 Media reporting and student campaigns have drawn attention to these issues, with little tangible impact on universities’ pursuit of expansion.27

While the focus in much coverage on international student numbers is on postgraduate students, growth in the number of non-EU international undergraduate students is also significant. This group increased in size by 60% at the University of Glasgow between 2018/19 and 2021/22, the highest growth rate in international undergraduate students of the ten largest universities in Scotland during the pandemic. The University of Edinburgh, numerically, has more international undergraduates (6,370 in 2021/22 compared to Glasgow’s 3,110) increased their number at a slower rate but still considerable rate of 38% over the same period.

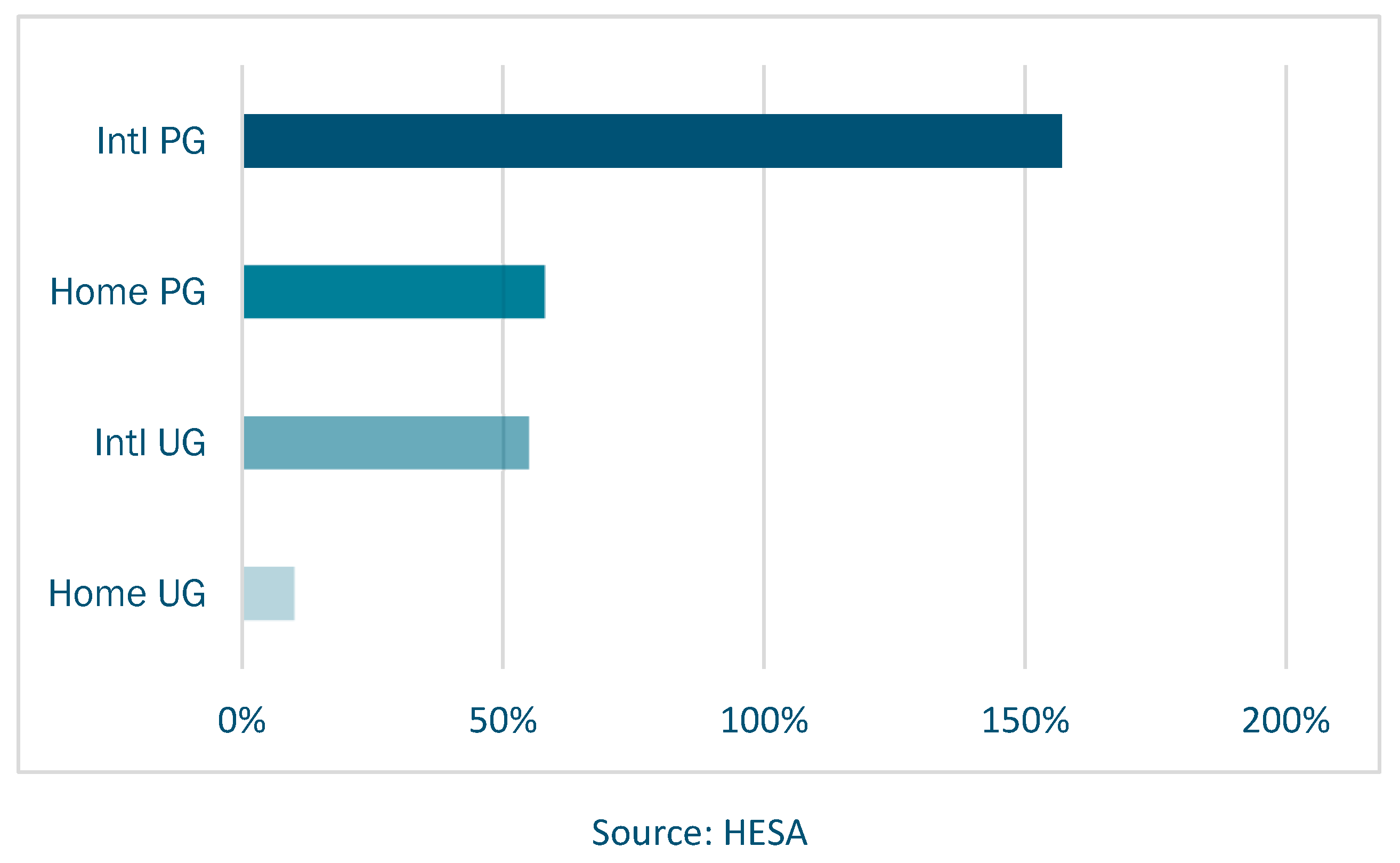

Comparisons of home and international, at undergraduate and postgraduate growth rates are shown for the university of Glasgow in the figure below. While home undergraduates still outnumber international undergraduates by three to one, the latter is growing at a much faster rate – 55% over three years (2018/19 to 2021/22), compared to around 10% growth in this period for home undergraduates.

Figure 10.

Percentage change in student numbers at the University of Glasgow – 2018/19 to 2021/22, by level of study and domicile.

Figure 10.

Percentage change in student numbers at the University of Glasgow – 2018/19 to 2021/22, by level of study and domicile.

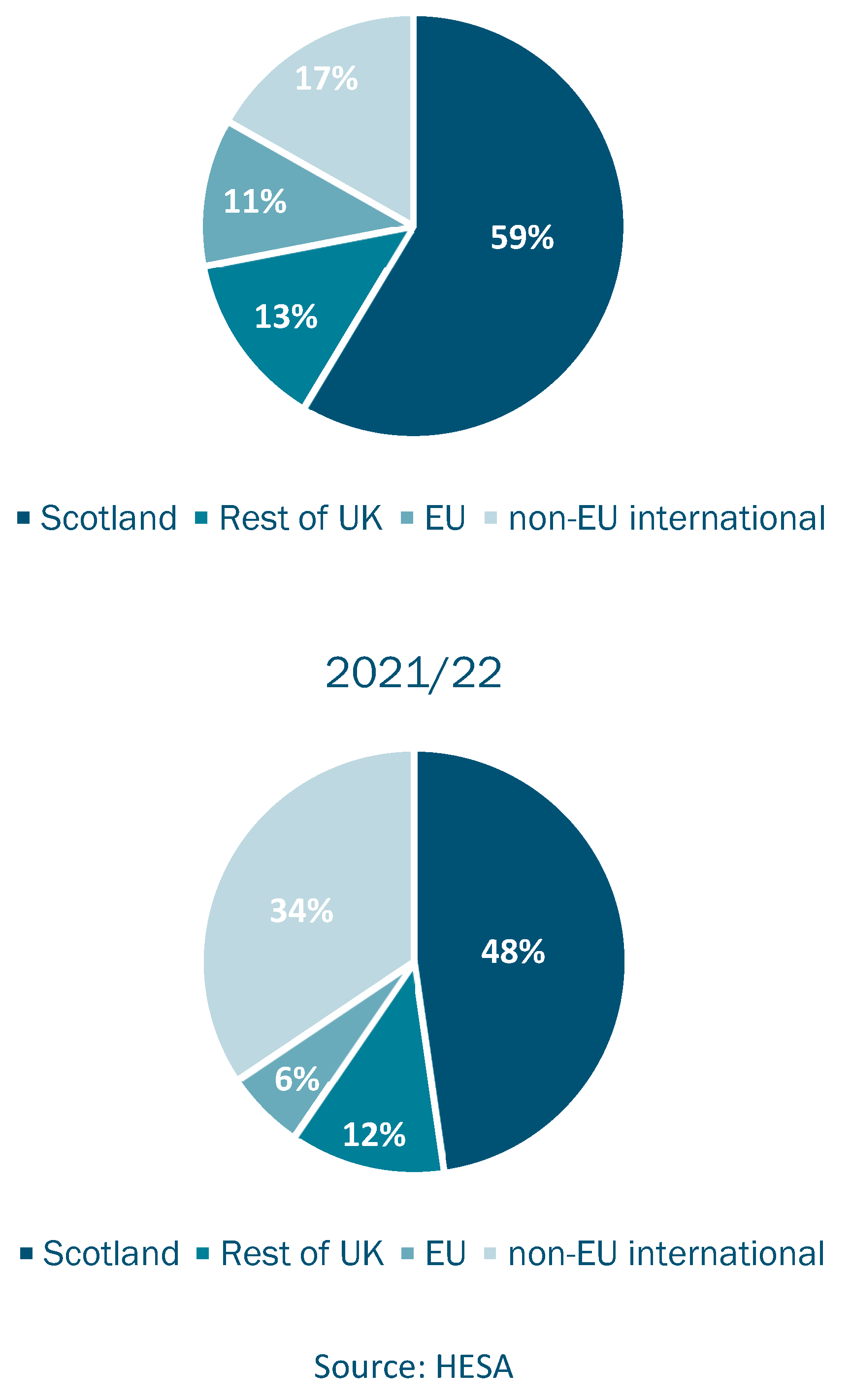

A neglected issue in the rapid expansion of international students in Scotland is the implication of this for those in Scotland seeking a university place. There are at least two dimensions to this. First are the potentially divergent admissions criteria for home compared to international students. Many universities have expanded international admissions by adjusting minimum entry requirements and English language tests for some programmes. Meanwhile, entry criteria for Scottish home undergraduates is becoming increasingly competitive at some universities for a range of reasons. Second is the limit on the total number of students a university can educate, given the finite spatial limits of a university campus, and a city. As more space is made to accommodate one category of students, less capacity exists for others. While numbers of students from the rest of the UK and EU are declining in many Scottish universities, a cause of some concern among university leaders, this has been more than overtaken by increases in international admissions. All of this is shifting student composition at Scottish universities, where one can observe, as shown below for the University of Glasgow the impact on especially EU and Scottish student participation.

Figure 11.

Changing domicile of Glasgow University students.

Figure 11.

Changing domicile of Glasgow University students.

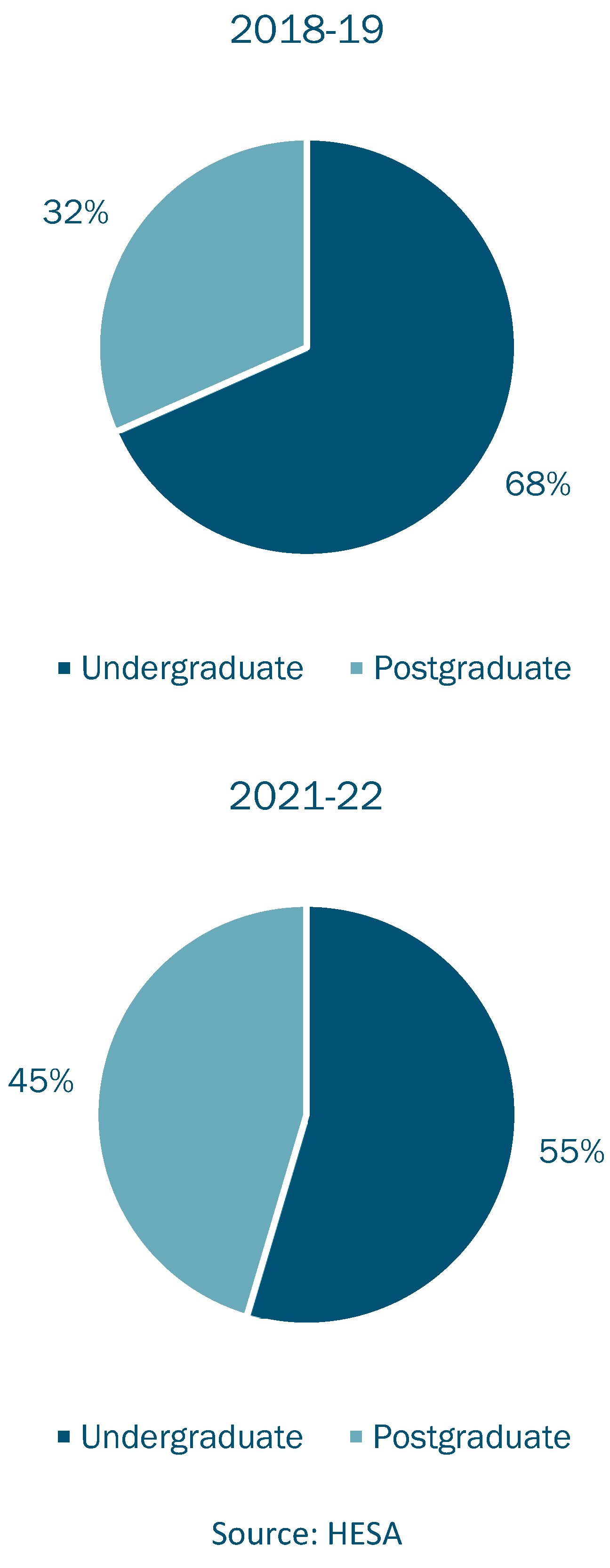

Before the pandemic, the University of Glasgow was primarily teaching an undergraduate population, with more than two-thirds in this category. After two years of pandemic, this university had shifted the balance of undergraduates and postgraduates considerably, to a 55:45 division.

Figure 12.

Balance of undergraduate to postgraduate students at the University of Glasgow.

Figure 12.

Balance of undergraduate to postgraduate students at the University of Glasgow.

Compare this profound change to the balance at the other two largest universities in Scotland – Edinburgh and Strathclyde. In 2018/19, they had a similar ratio as Glasgow of about two-thirds undergraduate to one-third postgraduate.28 In 2021/22, these two universities had maintained the same proportions.29 The University of Glasgow more than any other university in Scotland is moving away from the prioritisation of undergraduate education. The Russell Group average for postgraduates as a proportion of all students is similar to Edinburgh and Strathclyde at 35%; Glasgow University ranks third highest in the UK, after LSE (57%) and UCL (49%), for having the greatest proportion of its students working at postgraduate level.30

Overall, the pandemic has seen rapid growth in both income and numbers of students for all larger Scottish Universities, with the University of Glasgow showing the most significant changes. The driver of this growth has been the active recruitment of students who can be charged the most for their education. It is important that presentation of these data are not misleadingly appropriated to feed racist, politically right-wing narratives (and behaviour) about declining educational opportunities for Scottish-based students. The numerous universities in Scotland mean home students have many options; the takeaway from this analysis should focus on the overall growth and shifting balances between and within Scottish universities as a starting point to consider its implications for learning and working environments. Inequality among universities themselves is one place to start, where some universities are drawing the lion’s share of the highest paying students.

The growth in international student recruitment is widely accompanied by institutional claims regarding diversity and global outlook, but what this paper has documented is the income growth behind this recruitment strategy. What this paper has not been able to document, and for which public data could not be found, is the thoughtful, inclusive and well-resourced support for increasing diversity via international student as well as other strategies. Indeed, HESA data provide ample documentation of increasing concentration of international students from a very small number of countries, which may be contributing to declining diversity on UK campuses. Moreover, public information on international student attainment and outcomes appears to be lacking. My personal experience of teaching and working with colleagues teaching high numbers of international students in Scotland is of increasing numbers being referred to plagiarism or having to re-sit and re-submit work. Having aggregate data on these metrics is crucial not only for accountability and oversight of income generation strategies but also in terms of assessing universties’ duty of care and achievement of charitable mission.

China remains the country from which most international students in the UK come. The issue of student recruitment from China is fraught in many ways. As an academic of Chinese descent, I am especially sensitive to the risk of feeding not only xenophobic perspectives but also of continuing to objectify a group of people who are discussed in management conversations as ‘markets’, and where ‘diversity’ refers to diversification of financial risk rather than something about human beings, and a meaningful conversation about their inclusion and academic excellence. With these concerns in mind, I draw attention to some specific country issues in student recruitment. Aggressive, by which I mean highly active, financed and marketed, recruitment of students from China has been ongoing for many years. In 2021/22, HESA data show that there were around 152,000 students coming from China to study in the UK. Nearly 21,000 of these students are at Scottish universities, meaning 14% of all students from China are in a part of the UK that has only 8% of the national population. The Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow together sponsor 10% of all students from China who are in the UK. Many of these students find themselves in classes surrounded by other students from China, from anecdotal discussions with colleagues, again raising questions about deployment of a diversity discourse. In addition, as stated in the 2023 London Economics report, after China, India and Nigeria now supply the most international students to UK universities. These latter two countries have much less wealth than the UK, and may have taken loans or come from families who have sacrificed to save the amount necessary to pay the high fees charged to international students, as some from China also may have done. The changes to student composition in Scottish universities therefore merits significant attention to the due diligence HEIs exercise in accepting, and in actively recruiting, students from these places. In addition to the lack of public information on international student outcomes, there appears to be none on graduation rates and levels of debt either.

III. Charitable purpose? Kaplan International Partnership

In contrast to the lack of information about financial costs to international students, there is considerable information on the money that is made from them. Tuition fees for degree programmes are an important income source but not the only way that such students generate money for universities. In addition, universities earn significant amounts from student accommodation and catering; in 2022 this was worth £29 million to the University of Glasgow.31 Another source of income comes from companies like Kaplan International, a for profit educational provider of pre-course preparation programmes and other student services.32 The Glasgow International College is a private limited company headed by a member of Glasgow University’s senior management team, that partners with Kaplan International’s subsidiary, Kaplan Glasgow Limited.33

Kaplan earns income from course preparation fees for international students, residential accommodation, and from a ‘commission received from the University [of Glasgow] for students who have successfully completed their course and progressed to the university.’34 Moreover, it makes money from universities who pay commissions for Kaplan to send it students who do not achieve minimum marks for entrance to a Glasgow University course.35 Hence, whether or not they make the grade for one university in a Kaplan course, international students are worth a lot of money to other universities in the UK given the fees they will pay once enrolled on their degree programmes. In other words, Kaplan facilitates an internal UK market, worth billions of pounds, in international students.

Glasgow University also makes money from Kaplan directly, noting in its 2021/22 annual report that it saw income ‘increases in partnership income from GIC Kaplan’. University financial statements do not break down the precise amount made from this arrangement, as this is categorised as ‘other income’, which in 2022 totalled £28 million and included other sources like Government funding for the repeated year Dentistry students had to do as a result of pandemic restrictions on clinical training.

The partnership of the University of Glasgow with Kaplan is the largest and most profitable such arrangement amongst all Kaplan partnerships with individual universities in the UK, as shown in the table below. This partnership has been steadily growing its income, including during the pandemic, as shown for Kaplan Glasgow. In 2021, Kaplan Glasgow Ltd. recorded £7.1 million in profit, distributing £5.7 million to shareholders.36

Table 6.

Annual turnover of Kaplan-University Partnership Subsidiaries.

Table 6.

Annual turnover of Kaplan-University Partnership Subsidiaries.

| Subsidiary |

2021 |

2019 |

2018 |

| Kap Glasgow |

£ 35 million |

£ 28 million |

£ 19 million |

| Kap Intl London |

28 million |

|

|

| Kap Liverpool |

14 million |

|

|

| Kap Nottingham |

13 million |

|

|

| Kap Brighton |

8 million |

|

|

| Kap UWE |

8 million |

|

|

| Kap Bournemouth |

4 million |

|

|

| Kap Essex |

4 million |

|

|

| Kap York |

0.048 million |

|

|

What Kaplan calls increased income and turnover, might also, from the position of international students, be described as the added cost of studying in the Global North. Accessing the education, and symbolic capital, of elite universities requires students to pay not only university fees, but fees to recruitment agents, to course preparation services such as Kaplan, and a range of other costs for additional services provided by the many companies involved in international university partnerships, of which Kaplan is only one, but an important one in the Scotland HE landscape. And of course the billions of pounds that Scottish Universities have made from international students does not reflect the overall cost of living these students will pay to be here. This section has sketched a range of income to be incorporated into the calculus by which international students have become a highly sought commodity in UK higher education. It also thereby shows that the high price of tuition for this group is only part of what international students must pay to gain access to UK education. The ethics of ‘international tuition mark-ups’ deserve much more attention than currently is the case in research and HE conferences.37

IV. Staff Changes during Covid-19

This analysis has focused on university income growth, and the student expansion which has driven this during the pandemic. I had not initially intended to include the impacts on staff of these changes. However, at the time of preparing this paper, an analysis of academic staff casualisation was completed by two researchers, which provides relevant information that exposes further consequences of rapid growth (providing one of the figures above on student numbers).38 The figure below, from Yusuf Imaad Khan’s 2023 work, shows Glasgow reduced the share of its academic staff on permanent contracts at a faster pace than other Russell Group universities. It is difficult not to speculate on the correlation between rapid expansion of students and increasing casualisation of the staff who will teach and support them.

Figure 13.

Russell Group staff casualisation.

Figure 13.

Russell Group staff casualisation.

Where does it end? Concluding discussion

This paper has shown that despite the tone of crisis about Covid-19’s impact on universities, and a chronic refrain of universities having unstable financial positions, Scottish universities, which mainly enjoy financial stability, increased income during the pandemic at a faster rate than they had done before it. This is not something which happens passively, without university involvement. It is the result of active expansion of international student numbers, with little external oversight or regulation. As a result of these efforts, student composition is fundamentally shifting by further concentrating university finances on one source of income. The University of Glasgow has been most active on this front, seeing faster growth in tuition income and students, leading to its reliance on this source that is out of step with other Scottish and Russell Group universities.

The data analysed in this report document these changes, but they cannot answer questions about why and how these changes have occurred. One can speculate on the reasons, and there is an interesting comparison to be done on introduction of tuition fees in England (which may explain why some Scottish universities are more reliant on international fees), but further work is needed.39 Ramping up already high international student recruitment may have been a response to a perceived potential crisis in student numbers at the start of the pandemic. But such frenzied growth may be precipitating another crisis. This is a crisis of multiple dimensions, not only entailed in the increasing dependence on one source of money. There is also the lack of infrastructure to support students coming from outside Scotland, and lack of support for existing residents living alongside them. There has been the well-reported impact of expansion on housing, creating access and affordability issues for residents beyond students. And there is the longer-term issue of access for students coming up through the Scottish secondary system, especially in light of HEI commitments to widening participation and the role of universities in building inclusive societies which address inequalities and deprivation.

In my own experience, at the University of Glasgow, the crisis is about the nature and experience of university, what it means and feels like to be in a university as we move out of the pandemic. In my case it means more students and larger class sizes, so that postgraduate teaching once run as seminars now are taught in, where a classroom can be found, lecture theatres. This has profoundly changed the nature of the learning environment, and for the staff coping with these numbers, worsened and impersonalised working conditions. Adding more staff does not magically solve these problems but can exacerbate them as staff navigate developing working relationships with ever more people and services and the overall university environment reaches a scale in which impersonal services are the norm. This is not likely to be the experience that students paying upwards of £40,000 or £60,000 per year expected, exposing universities to significant reputational risk as well.

For most Scottish universities, a pandemic crisis narrative belies actual financial need; as noted the University of Glasgow which has pursued international student growth more assertively than any other university in Scotland, already had the highest surplus to deficit ratio among all Scottish universities in 2021, the year before its record income in 2022.40 Some Scottish universities are continuing to report deficits through this period of growth, and ambitious campus redevelopment projects (which will support further student and global reputation growth) are an important contributor to this.41 Looking at university annual reports, rapid expansion does not appear to have been guided by any strategic or collective vision of education. Rather a circular logic arises in these documents, where increased income from student growth is lauded for allowing more investment (in buildings, amenities, high profile appointments) that raises the global profile of the university that in turn will increase global student numbers.

Universities have also embraced of the ideal of the ‘civic university’ entailing commitments to support regeneration – economically, culturally, socially – in surrounding communities and a beacon globally, tied to such markers as the UN’s sustainable development goals.42 The growth pattern at the University of Glasgow, whose pattern may be a sign or a warning of the paths of other Scottish HEIs, reflects little engagement with core aspects of its values and strategy, and its leaders have not explicitly addressed how expanding size risks transforming cities like Glasgow in terms of affordability, sustainability and liveability for both students and non-students. The changing balance of where students are from and between postgraduate and undergraduate students at this university is reconfiguring the main activities of the university – teaching and research – with the long-term implications of this under studied. One area of concern is how the focus on international growth will bode for the accessibility of university education for students in Scotland. The students who are going through the university at this time of unprecedented period are directly aware of what is happening, and at Glasgow University have had their attempts to cap numbers and address housing costs and shortages rejected.43

International students are also becoming increasingly vocal about, though not yet effectively collectivised, their status as sources of income drivers. Despite a fashion for ‘decolonising the curriculum’ the message being sent through international income capture is clear: the most prestigious and respected education remains a very high priced one uniquely available from elite institutions of the Global North. Equally troubling is the market for international students, exemplified in Kaplan International’s business model, which involves commissions and finders’ fees for pushing, sometimes struggling, students to different UK institutions. The universities who benefit from this trade are rarely called to account for their role in this.

Where some academics held out hope or actively called for more progressive work practices and a more caring ethos to become the legacy of living through pandemic, this has not been evidenced in university actions.44 In the case of the University of Glasgow, the institution that has been the focus of this paper, one wonders what end point is envisioned, what ultimate goal might be achieved by its unprecedented expansion and reconfiguration, and how are the staff and students caught up in this a part of or instrumental to it? Increasingly I feel as if my role as a teacher is shifting from working with and alongside students to nurture their curiosity about the world to a transactional relationship where I struggle against burnout to deliver a service that can justify its price.45

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to the colleagues across the university sector who took the time to read this paper in its various drafts, provide feedback, audit my numbers and suggest edits or corrections. I have attempted to integrate these, though the responsibility for the positions and interpretations, and any errors, within it are mine alone.

References

- Armstrong, S. and Fletcher, M. (2021) “It starts with conversations”: Report on Civic Engagement in the College of Social Sciences. University of Glasgow.

- BBC (2023) ‘Glasgow University to increase rents by nearly 10%’ (17 February) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-64678528.

- BBC (2022) ‘Glasgow students without flats told to consider quitting university’ (22 September) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-62982938 .

- BBC (2022) ‘Glasgow students denied university accommodation’ (11 August), https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-62493966.

- BBC (2021) ‘Scotland's students face accommodation “nightmare”’ (7 October) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-58822372.

- Brackley, J. (2023) ‘Addicted to growth? What we know about Higher Education Finances’, blog, Centre for Research into Accounting and Finance in Context, University of Sheffield, https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/crafic/news/addicted-growth-what-we-know-about-higher-education-finances.

- British Universities Finance Directors Group (BUFDG) (2021) A BUFDG Guide to University Finance, (September, revised version); available online: https://www.bufdg.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/understanding-finance/.

- Canadian Association of University Teachers (2016) Guide to Analyzing University & College Financial Statements; available online: https://www.caut.ca/latest/2016/09/caut-launches-guide-read-university-and-college-financial-statements.

- Cannings, J., Halterbeck, M. and Conlon, G. (2023) The benefits and costs of international higher education students to the UK economy, Consultancy Report, London Economics (May 2023). Available online: https://londoneconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/LE-Benefits-and-costs-of-international-HE-students-Full-Report-2.pdf.

- Chafer, L. (2023) ‘UofG rejects central demand of SRC Cap Student numbers campaign’, The Glasgow Guardian (7 January) https://glasgowguardian.co.uk/2023/01/07/uofg-rejects-central-demand-of-src-cap-student-numbers-campaign/.

- Corbera, E., Anguelovski, I., Honey-Rosés, J. and Ruiz- Mallén, I. (2020) ‘Academia in the Time of COVID-19: Towards an Ethics of Care’, Planning Theory & Practice, 21:2, 191-199. [CrossRef]

- Estermann, T., Bennetot Pruvot, E., Kupriyanova, V. and Stoyanova, H. (2020) The impact of the Covid-19 crisis on university funding in Europe: Lessons from the 2008 global financial crisis, European University Association Briefing (May); available online: https://www.eua.eu/downloads/publications/eua%20briefing_the%20impact%20of%20the%20covid-19%20crisis%20on%20university%20funding%20in%20europe.pdf.

- Gaskill, M. (2020) ‘On Quitting Academia’, London Review of Books Vol. 42(18) (24 September); https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n18/malcolm-gaskill/diary .

- Gillies, C. (2022) ‘Students “begging” letting agents for flats.’ BBC online (11 October) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-63206999 .

- Jenkins, S. (2023) ‘British universities can no longer financially depend on foreign students. They must reform to survive’, The Guardian (2 June) https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/02/british-universities-foreign-students-deficits-government-higher-education.

- Kernohan, D. (2023) ‘Nicola Sturgeon’s higher education legacy’, Wonk HE blog, https://wonkhe.com/wonk-corner/nicola-sturgeons-higher-education-legacy/.

- Khan, Y.I. (2023) Academic casualisation across the UK, blog; https://www.yusufimaadkhan.com/posts/lseucu_casualisation_yik/#the-russell-group-or-the-hustle-group.

- Lieutaud, M. (2023) The Crisis of Academic Casualisation at LSE – LSE UCU Report; available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1FQiPscs_epkMnBdPyp-h8Wosyuw1oWVgsOHnFivDELE/edit.

- McGettigan, A. (2020) ‘Understanding University & College Finances’, UCU Webinar presentation (8 July); available online: https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/11001/Understanding-institution-finances-Andrew-McGettigan/pdf/mcGettigan_understanding-he-finances_jul20.pdf.

- Packer, H. (2023) ‘UK international student fee markups “problematic” – IHEF 2023’ The PIE News; https://thepienews.com/news/international-student-fee-markups-ihef/.

- Ward, S. (2022) Top university tells students to drop out if they can’t find somewhere to live, The Independent (18 November) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/housing-shortage-university-of-glasgow-b2227907.html.

- Weale, S. (2023) ‘International students boosted UK economy by £42bn in 2021/2 – study’, The Guardian (16 May); https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/may/16/international-students-boosted-uk-economy-by-42bn-in-20212-study .

- Weale, S. and Quinn, B. (2023) ‘English universities warned not to over-rely on fees of students from China’, The Guardian (18 May); m https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/may/18/english-universities-warned-not-to-over-rely-on-fees-of-students-from-china.

- Williams, R. Manly, L., Pritchard, A., Halterbeck, M. and Conlon, G. (2021) The economic impact of the University of Glasgow, Consultancy Report, London Economics (October 2021)). Available online https://londoneconomics.co.uk/blog/publication/the-economic-impact-of-the-university-of-glasgow-october-2021/.

| 1 |

University of Glasgow, Annual Report and Financial Statements 2021/22. University of Edinburgh, Annual Report and Accounts for the Year to 31 July 2022. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

LE (2023), The benefits and costs of international higher education students to the UK economy, p. ix. |

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

Some universities may refer to student ‘FTEs’ (full-time equivalents) as a measure of student numbers, which has the effect of reducing their total student population. FTEs treats, for example, two -part-time students as one person. While every counting mechanism has limitations, an FTE approach has some particular limits relevant to the issues raised here. As only one example, two part-time students both need housing, and so counting them as 1 FTE under plays the impact of student numbers on accommodation. Hence part-time status does not reduce the housing impact on a city or university accommodation resources. This analysis uses the data that is reported by universities themselves to HESA for student numbers, and which allows comparison across institutions. |

| 7 |

E.g. BUFDG (2021) A BUFDG Guide to University Finance, (September, revised version); Canadian Association of University Teachers (2016) Guide to Analyzing University & College Financial Statements; and A McGettigan (2020) ‘Understanding University & College Finances’, UCU Webinar presentation. |

| 8 |

Thomas Estermann et al. (2020) The impact of the Covid-19 crisis on university funding in Europe: Lessons from the 2008 global financial crisis, European University Association Briefing (May), p. 3. |

| 9 |

Ibid, p. 11. |

| 10 |

That is, if income had grown at the same rate during 2020-22 as it had between 2017 and 2019, then the university would have earned £107 million less than it actually did. |

| 11 |

Different terms are used to refer to such students. Most Scottish University annual reports (and indeed HESA data) continue to categorise students as: home (Scotland-domiciled), rest of UK, EU and non-EU; after Brexit, there is no difference between EU and non-EU fees. This report analyses data specifically for non-EU students, meaning that it slightly undercounts the numbers of student and amount of income of international student participation. |

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

The annual reports from these universities showed that income from non-EU international students increased between 2019 and 2022 as follows: GCU went from £9.4 million in 2019 to £23.2 million (146% increase); UWS, £8.1 million to £30.1 million (272%); Stirling, £15.8 million to £31 million (96%); and Glasgow $142 million to £281.5 million (98%). |

| 15 |

See income and expenditure statements in the annual reports for these years. |

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

GU financial statements combined EU and home students in the same income category prior to 2020. |

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Napier, GCU, Glasgow, St Andrews, Stirling, Strathclyde, UWS. |

| 22 |

HESA, 2021-22. See earlier note about counting conventions. |

| 23 |

HESA, 2021-22. The Open University has the most students of all UK universities but is excluded as a non-traditional HEI with no physical campus. |

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

Op. cit., London Economics (2021, 2023). |

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

HESA data shows both had 66% undergraduate and 34% postgraduate students. |

| 29 |

There was a slight shift upwards of postgraduates, with Edinburgh and Strathclyde both having the same percentages of 37% postgraduate to 63% undergraduate students. |

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

The overarching corporation, is Kaplan International Colleges U.K. Limited (Companies House number 05268303), under which its subsidiaries operate in partnership with a university-affiliated ‘international college’ and collectively are referred to by Kaplan International as ‘the Group’. The Group has an ‘international network of of representative offices engaging in recruitment and marketing services…the largest of which are in India, Hong Kong, UAE and Nigeria’ (Kaplan Internatonal Colleges, UK, Ltd. Annual Report and Financial Statements through 26 December 2020, p. 1). Subsidiary companies are listed on p. 45 of the Annual Report and Financial Statements document. |

| 33 |

Companies House. GIC is listed as a ‘dormant’ company with £1 of assets that is the corporate body and brand through which Kaplan delivers its courses. |

| 34 |

Kaplan Glasgow Limited, Annual Report and Financial Statements December 2021, p. 1, accessed via Companies House. The company leased two student accommodation buildings from University of Glasgow, but in 2022, Glasgow University ended the lease and now operates and earns income directly from these halls. |

| 35 |

‘The Company seeks to recruit students for progression onto the University by maintaining awareness of the Pathway Courses offered through marketing opportunities undertaken by fellow Kaplan entities’ (Annual Report and Financial Statements through 25 December 2021, p. 1, filed July 2022). Kaplan’s GIC web page states: ‘Students who pass their pathway course but don’t meet the progression requirements for their chosen University of Glasgow degree are guaranteed a place at a UK university through our University Placement Service.’ The placement service is a network of Kaplan-university partnerships across the UK that ensures that, for students who pass their course but without the grades required by Glasgow University: ‘they can still find a place at a UK university’ where ‘Universities will be able to review your profile and make you an offer if you meet their requirements’ (Kaplan Pathways website). Kaplan Nottingham Ltd conveys the active recruitment function in the market for students in adding this line about its business activities: ‘and by having third party-recruitment agents visit the college’, (Annual Report and Financial Statements, through 25 December 2021, filed July 2022). |

| 36 |

Id., p. 11. The 2021 financial statements of Kaplan International U.K., Ltd. noted profits from its group totalled £12 million on £133 million of revenue; thus Kaplan Glasgow accounted for half of all profit made by the Group in the UK (see Companies House annual report and financial statements through 25 December 2021, p. 1). |

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

Op. Cit. Kernohan (2023). |

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

Another key factor has been claimed flawed pension valuations, a contentious issue and the subject of the current labour dispute in higher education. |

| 42 |

E.g., https://www.gla.ac.uk/explore/unsdgs/ and The Economic Impact of the University of Glasgow (London Economics, 2021), especially Chapter 7 on inclusive, sustainable growth and tackling inequalities. |

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

Esteve Corbera , Isabelle Anguelovski , Jordi Honey-Rosés & Isabel Ruiz- Mallén (2020) Academia in the Time of COVID-19: Towards an Ethics of Care, Planning Theory & Practice, 21:2, 191-199, DOI: 10.1080/14649357.2020.1757891. And, see, Sarah Armstrong and Maria Fletcher (2021) “It starts with conversations”: Report on Civic Engagement in the College of Social Sciences. University of Glasgow. |

| 45 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).