Introduction

Cancers of the head and neck and their treatment can cause various degrees of disfigurement and loss of functioning, with a profound negative impact on the person’s self-image and psychological and social wellbeing (Alias & Henry, 2018; De Graeff et al., 1999; Dropkin, 2001; Melissant et al., 2021). This can lead to experiences of shame and stigma (Henry et al., 2022). Shame is a psychological state in which the person experiences a sense of disgrace, dishonour, or humiliation, and a desire to cover up, hide, or escape (Lewis, 1971). Stigma involves social disapproval regarding the person’s identity or disfigurement (Goffman, 2009). Experiences of shame and stigma in cancer patients are associated with low self-esteem, depression, social isolation (De Graeff et al., 1999; Gamba et al., 1992; Gonzalez & Jacobsen, 2012; Pruyn et al., 1986), and deteriorating family relationships despite physical improvement (Bjordal & Kaasa, 1995). Head and neck cancer patients also often experience guilt and regret about past behaviours (Rhoten et al., 2013), such as smoking or drinking, that may have contributed to the cancer (Dearing et al., 2005; Ostroff et al., 1995).

Shame, stigma, and regret are important targets for psychosocial interventions with head and neck cancer patients, in order to help patients to modify their negative perceptions and develop acceptance and accommodation (Kissane et al., 2012). Accurate measurement (Shunmuga Sundaram et al., 2019) and identification of these problems enables clinicians to offer appropriate interventions and monitor patients’ progress. It also contributes to a better understanding of the prevalence of shame and stigma and their impact on patients’ lives (Kissane et al., 2012).

In response to the above needs, Kissane et al. (2012) developed and validated the Shame and Stigma Scale (SSS) at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in the US. Since then the scale has been translated and validated in seven different countries (Goyal et al., 2021) and has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of shame and stigma.

The aim of the current study was to validate the scale among French and English speaking Canadian head and neck cancer patients. It is important to explore the scale’s functioning in different cultural and language contexts, and to adapt it to these specific needs if necessary. This appears particularly important considering the known detrimental effects of shame and stigma on physical and mental health outcomes, and it’s target as a public health concern by Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer (Tam, 2019).

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Procedure

Patients were recruited through the Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery departments of two large Canadian hospitals affiliated with McGill University. Eligible patients had undergone a disfiguring surgery less than three years from the time of referral. The type of surgery was defined in consultation with medical teams. Patients were mailed the study questionnaires which they returned by mail in prestamped preaddressed envelopes. Two weeks later patients were resent the questionnaires again. Them recruitment procedure is described in more details elsewhere, in a study led by one of the authors, Melissa Henry (Rodriguez et al., 2019).

Measures

The following well validated measures were used in the current study: Shame and Stigma Scale (SSS) (Kissane et al., 2012) (the English version and a French translation were used), Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory (BICSI) (Cash et al., 2005), Body Image Scale (BIS) (Hopwood et al., 2001), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Bjelland et al., 2002; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), Centre of Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977), Illness Intrusion Ratings Scale (IIRS) (Devins, 2010; Devins et al., 1984), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) (Cella et al., 1993) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Head and Neck (FACT-H&N) (List et al., 1996), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire-Short Form (BPAQ) (Buss & Perry, 1992; Diamond & Magaletta, 2006), and the Marlowe-Crown Social Desirability-Short Form (MCSD) (Fischer & Fick, 1993; Reynolds, 1982). The SSS was translated into French using back-translation (Vallerand, 1989).

Statistical Analysis

To assess the factor structure of the SSS exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the polychoric correlations matrix of the items. Using polychoric correlations is more appropriate for ordinal data than the Pearson correlations (Flora & Curran, 2004). An oblique Promax rotation was used, allowing correlations between the factors. Eigen values ≥1 and the Scree plot were considered in factor selection, as well as conceptual considerations of factor interpretability.

Descriptive statistics, such as means, medians, and response frequencies were derived for each SSS subscale and for each item. Internal consistency reliabilities (Chronbach’s α) and test-retest reliabilities were also calculated. Sperman’s rho was used for the test-retest reliability due to the skewness of the data.

Covergent and divergent validity was examined by calculation of Spearman’s rho correlations between the SSS and its subscales and the other measures used in the study. It was expected that the SSS would have stronger asociations with appearance related scales, such as the BICSI, BIS, FACT-G and FACT H&N, as well as at least moderate correlations with the psychological distress ( the HADS and CES-D) and interference of illness with life (IIRS). The SSS was expected to have relatively weaker associations with the aggression (PAQ) and social desirability (MCSD) scales.

Rasch (Rasch, 1960) analysis was used to further investigate the psychometric properties of the SSS based on item level information and the respondents pattern of responses to each item. Rasch is a probabilistic model which estimates each respondent’s ability (or level of the measured attribute) and each item’s difficulty (or level of the attribute measured by the item) on the same scale with logits as the measuring units (Bond & Fox, 2013). The Rasch analysis was used to evaluate overall model fit, item fit, unidimensionality, potential item bias between subgroups of respondents, and how well the items are targeting the respondents. A good overall model fit is indicated by a non-significant λ2 (with a Bonferroni adjustment for the number of items), and an an overall item fit residual standard deviation below the accepted limit of < 1.5. Individual item fit is indicated by item standardised residuals within the accepted range of >-2.5 and <2.5. High item interdependencies are indicated by item residual correlations ≥0.2 (Marais & Andrich, 2008). Internal consistency was assessed with the Person Separation Index (PSI) estimated by Rasch, and with Cronbach’s α. The PSI is interpreted similarly to α, with values ≥ 0.70 considered good (Marais & Andrich, 2008). Targeting (or the allignment of the item difficulty and person ability levels) was assessed by examining the person-item threshold distribution. Differential Item Functioning (DIF) refers to item bias or differential item performance (Pallant & Tennant, 2007). DIF for language in which the scale was completed (French or English), sex, age, and education was examined with analysis of variance comparing Rasch scores for each level of these variables across each item. Item thresholds (the points between each adjacent response category where either of the adjacent responses is equally likely) were tested for disordering (when responses are not ordered as expected, low to high). Unidimensionality of each subscale and the whole scale was assessed by using t-tests between the Rasch-derived scores of subsets of items identified by principal component analysis on the residual correlations. Unidimensionality is confirmed if significantly less than 5% of the t-tests are significant (Tennant & Conaghan, 2007). Our sample of 254 patients was adequate for Rasch analysis. A minimum of 150 participants are required to estimate item difficulty within ±0.5 logits accuracy (Linacre, 1994).

Rasch analysis was conducted with the RUMM2030 (Andrich et al., 2011) software using the partial credit model (Masters, 1982). All other analysis was conducted with Stata 17 (StataCorp, 2021).

Results

Description of the Study Population

Data from 258 patients was collected and analysed. Of the study population 55% were recruited from the Jewish General Hospital and 44% from the McGill University Health Centre. The questionnaires were completed in French by 53% and in English by 47% of the sample. Of the sample 67% were male; median age was 67 years with a range 23-98 years; 64% were partnered; and 34% completed at least high school and 42% had tertiary education. The most common forms of cancer were cutaneous (38%), oral cavity (21%), and oropharynx (12%). Of the sample 14% had advanced Stage IV cancer, 29% Stage III, 23% Stage II, and 18% Stage I. The demographics of the study population are described in detail elsewhere (Rodriguez et al., 2019).

Factor Analysis of the Shame and Stigma Scale

Four factors were derived from the exploratory factor analysis (

Table 1), consistent with Kissane et al’s (2012) original validation of the scale. There were several cross-loading items which had a lower or similar loading on two factors, but they were retained in the factor they conceptually fitted most with, in line with the original scale. Item 9 was the only one which did not load as expected. Overall, the results supported the 4-factor structure of the original scale. The four factors were: Sense of Stigma (8 items), Shame with Appearance (6 items), Regret (3 items), and Social/Speech Concerns (3 items). The correlations between the factors were moderate in size and similar to those obtained in Kissane et al.’s (2012) original validation, ranging from .27 to .46.

Descriptive Statistics for the Subscales and Items of the SSS

Table 2 shows that the first three scales had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α from .76 to .82) and test-retest reliability (Spearman’s rho from .60 to .73). The Social/Speech Concerns subscale had lower internal consistency of .52. The Sense of Stigma Scale had a substantial floor effect, with nearly half the scores being zero. The medians and means of the subscales and the complete scales were fairly low.

Table 3 shows good corrected correlations between the items and their subscales and the total scale. Item 20 has the lowest correlation with the total scale (.24). For most items very low proportions of the participants obtained high scores above 3. There was a substantial floor effect for many of the items. The results in

Table 2 and

Table 3 indicate skewed data, with only a small proportion of participants scoring in the high range of the item response categories.

The convergent and divergent validity correlations (

Table 4) follow the expected pattern. The Shame with Appearance scale had the strongest correlations with the appearance related scales (BICSI, BIS, FACT-G and FACT H&N). All SSS subscales were weakly to moderately correlated to the depression and anxiety scales (GADS and CES-D) and illness interference with life (IIRS). The weakest correlations for all subscales were with the aggression (PAQ) and social desirability (MSCD) scales.

Rasch Analysis

A summary of the Rasch analysis for each SSS subscale and the total scale is presented in

Table 5. The Rasch analysis suggested that the Canadian version of the SSS would be improved by removing four items: 8, 9, 17, and 20.

On the Shame with Appearance subscale, item 8 (“I am distressed by the changes in my face and neck”) showed significant DIF in language, with respondents who completed the scale in English consistently scoring higher than expected on this item and those who completed it in French scoring lower. After item 8 was removed there was no remaining DIF and the model fit and PSI were adequate.

The Sense of Stigma subscale initially showed some misfit, with a significant χ2 for the overall model fit, although the item residual standard deviation and the PSI were within the acceptable limits. This subscale contained Item 9 (“I feel others consider me responsible for my cancer”), which on the factor analysis loaded on only the Regret subscale. In the original validation of the SSS item 9 was included in the Sense of Stigma subscale for conceptual reasons, but on the factor analysis it also loaded on Regret and Social/Speech Concerns. In the Canadian version removing item 9 improved the fit of the Sense of Stigma subscale, with the overall model fit χ2 becoming non-significant, and the item residual standard deviation and the PSI improving slightly.

Item 17 (“I feel sorry about the things I have done in the past”) of the Regret subscale showed significant DIF for language, with French speakers scoring higher than expected and English speakers lower. Removing Item 17 reduced the PSI from .56 to .37, however, α remained adequate at .71. Since this is only a 2-item scale with items targeted towards high scoring respondents, this model fit is acceptable despite the low PSI.

The Social/Speech Concerns subscale showed an overall model misfit with a highly significant χ2, and the PSI could not be estimated properly. Cronbach’s α was also low (.52). All items showed misfit with a highly significant χ2 (p<.0001), with item 20 (“I am able to join conversations”) having a large fit residual (2.35), close to the ≤2.5 limit. After deleting Item 20 an adequate model fit was obtained and α improved to .79, suggesting good internal consistency. Item 20 also showed misfit in Kissane et al.’s (2012) original validation of the SSS, with an indication that some patients may have responded to it as a negatively worded item. Item 20 is a positively worded item after a row of 12 negatively worded items, which may have caused confusion among respondents.

The PSI for the Sense of Stigma, Regret, and Social/Speech concerns scales were below the acceptable value of .70, while Shame with Appearance and the total scale had acceptable PSIs. All subscales and the total scale had acceptable Cronbach’s α values. Both the PSI and α are measures of internal consistency reliability. While α is calculated from raw scores, the PSI is based on estimated Rasch person locations. If the scale’s item difficulties and person abilities are well aligned, α and PSI are close in value. A misalignment in a skewed distribution results in a discrepancy between α and PSI, since with more extreme person scores, the error variance of the PSI increases but α remains more constant (Andrich et al., 2011). In the current sample there was a large proportion of respondents who mainly endorsed zero or the low end of the item categories, few high scoring respondents, and subscales with a small number of items. This would explain the discrepancy between PSI and α, as well as obtaining low PSIs of the most misaligned subscales. In the total SSS, with an increased number of items covering a wider range of person abilities the PSI improved to .81. Overall, the acceptable α values, combined with good fit of the models, indicate that the subscales had adequate psychometric properties. However, they are better targeted to a population with a higher level of shame and stigma than the current sample.

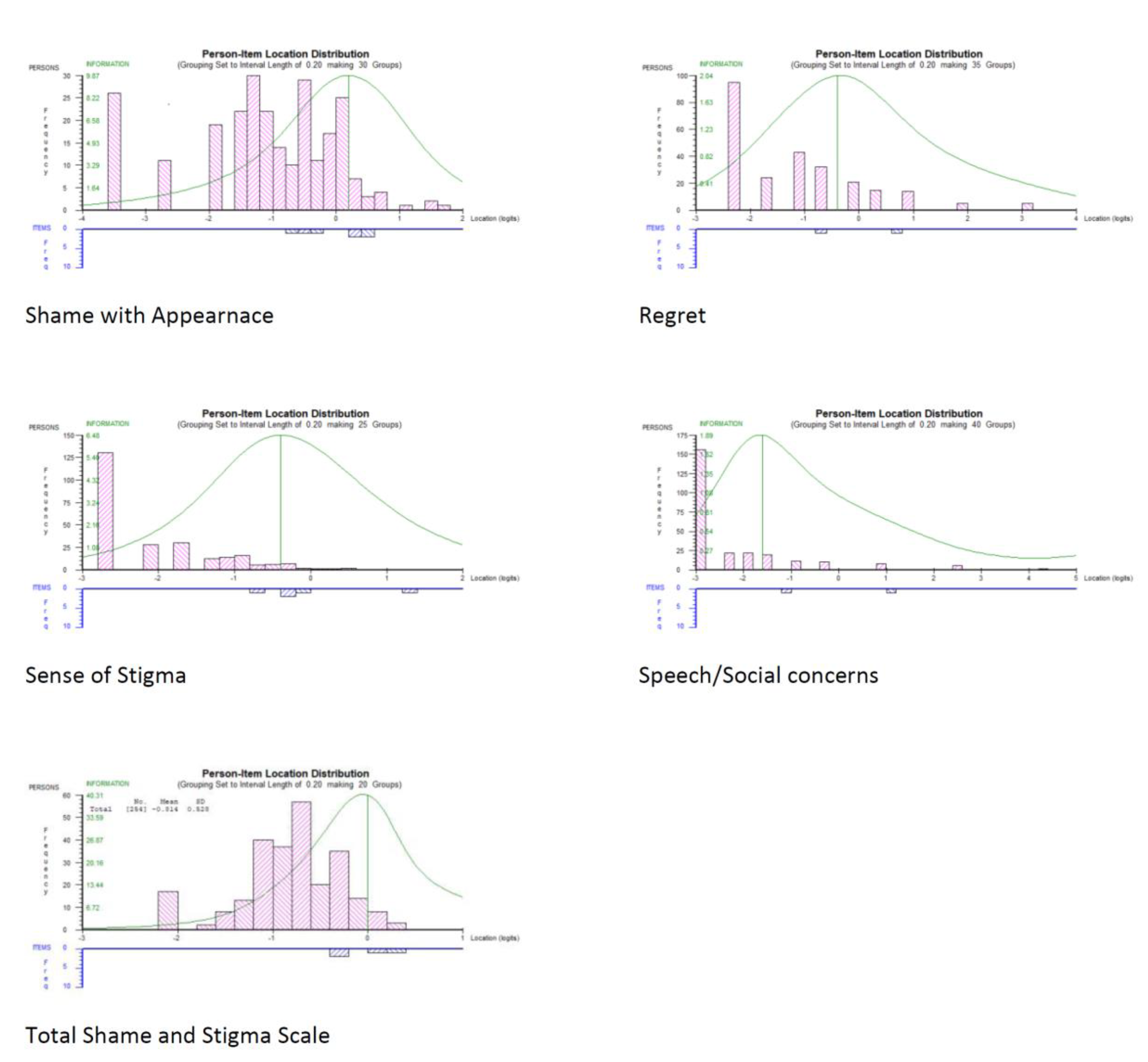

Figure 1, showing the item-person locations distributions, illustrates that most items were targeted towards the higher range of difficulties, while persons are mainly located at the lower end of the distribution.

All subscales and the total scale were unidimensional, with none having significantly more than 5% of significant unidimensionality t-tests.

All item thresholds, except for item 5 (“I feel people stare at me”) were disordered. Collapsing the item response options into fewer categories (Never, Seldom/Sometimes, Often/All the time) resulted in ordered thresholds but did not affect the fit of the models. Collapsing of categories results in loss of statistical information and decreases reliability. Disordered thresholds may not always represent a violation of the intended order of item response categories. They may be a result of low frequencies of responses in some categories (Adams et al., 2012; Linacre, 2002, 2004; Masters, 1982). In our sample there was a high proportion of zero (“Never”) responses and low proportions for most items of “Often” or “All the time” responses. In Kissane et al.’s (2012) original validation of the SSS, in which the data was less skewed, the thresholds were ordered. Kissane et al.’s sample was restricted to oral cavity cancers with potentially more severe symptoms, whereas in our sample 38% of patients had cutaneous cancers with less severe symptoms, thus restricting the SSS range. Furthermore, we found that in our data the average Rasch estimated person abilities increased monotonically as item response categories advanced from 0 to 4 for each SSS item. This suggests that patients responded to the items as intended and the item categories represent advancing levels of shame and stigma (Linacre, 2002, 2004). Based on the above evidence, it was decided to retain the existing item categories.

The final version of the Canadian SSS is presented in Appendix 1.

Discussion

Despite the morbidity that the diagnosis and treatment of head and neck cancer brings, there has been a relative paucity of validated measures that are specific to the needs of this population (Ellis et al., 2019). Here we take just such a measure and validate it for the mixed language needs of a Canadian population. The only other related measure having been validated in English and French in a Canadian context has been the McGill Body Image Concerns Scale for use in head and neck oncology (MBIS-HNC). The latter is comprised of two subscales: social discomfort and negative self-image. It focuses more specifically on changes in appearance, function and senses as a result of head and neck cancer treatments (Rodriguez et al., 2019). Rodriguez et al. (2019) reported moderate to high correlations between the MBIS-HNC and the SSS subscales (.49 with Regret, .50 with Social/Speech Concerns, .55 with Sense of Stigma, and .72 with Shame about Appearance). This suggests that the two scales have good convergent validity, but measure different constructs.

We have shown the Shame and Stigma Scale to be a reliable and valid measure and to have adequate psychometric properties in a Canadian population of cancer patients. The factor structure of the original SSS was supported, with the existing four subscales: Shame with Appearance, Sense of Stigma, Regret, and Social/Speech Concerns. The Canadian version of the SSS showed adequate convergent and divergent validity and test-retest reliability. The SSS followed the expected pattern, of having stronger associations with measures of concerns about appearance, psychological distress, and life interference from illness. The SSS had weaker associations with less related constructs, such as aggression and social desirability.

We have suggested scale improvements by removing two misfitting item (items 9 and 20) and two items with differential functioning between French and English speaking patients (items 8 and 17) to adapt it to the Canadian population. Item 9 did not load as expected in the factor analysis and caused model misfit in the Rasch analysis. This item also crossloaded on multiple factors in Kissane et al.’s (2012) validation. Item 20 caused misfit in the Rasch model and was also found problematic in Kissane et al.’s validation. It was important to remove the differentially functioning items 8 and 17, so that the scale functions equivalently for both French and English speaking Canadians. The final scale version had adequate fit to the Rasch model. The unidimensionality of the subscales and the total scale was confirmed.

In comparison to our study, validations in five other countries also supported the four factors structure of the SSS. The Taiwanese (Tseng et al., 2019) and Malay (Zhang et al., 2022) versions extracted five and three factors respectively. In the Malay (Zhang et al., 2022) version all of the four positively worded items (1, 4, 7, and 20) were removed, and in the Chinese (Cai et al., 2022) version items 1 and 4 were removed, since they did not perform well. These two studies raised issues about translating opposite wording items to different cultures. We note that the positively worded item 20 also exhibited problematic fit in our study and in the original validation (Kissane et al., 2012).

Our study, as well as Kissane et al.’s (2012) original validation, showed that the items of the SSS are targeted towards higher levels of shame and stigma severity. This means that the scale provides more accurate measures for people with high levels of shame and stigma. Thus, the SSS has utility in identifying patients with severe levels of shame and stigma who may be in need of psychosocial interventions. The SSS could also useful for monitoring the progress of interventions.

Strengths and Limitations

The study had a sample of adequate size and representativeness. Patients from two different health settings and a range of socioeconomic groups were recruited, and French and English speaking participants were approximately equally represented. A limitation of the study is that most patients had low levels of shame and stigma, while the SSS is targeted towards the high end of the distributions. The scale would provide less precise assessment for people with low levels of shame and stigma. For many of the SSS items the highest categories “Often” and “Sometimes” had very low response frequencies. This may have contributed to disordered thresholds in the Rasch model (Adams et al., 2012; Linacre, 2002, 2004; Masters, 1982). Our data indicated that, nevertheless, the response options were functioning as intended. The Rasch estimated person abilities (levels of shame and stigma) increased monotonically with higher response categories for all items (Linacre, 2002, 2004). However, further investigation of how the item response categories and Rasch estimated thresholds function in less skewed data is warranted in future studies. Further work to investigate how the SSS generalises to other types of cancer and other cultural groups is also needed.

Conclusions

This study has provided evidence of the reliability and validity of the SSS in a Canadian population of cancer patients. The SSS is a promising tool for identifying patients with high levels of shame and stigma in clinical settings in Canada, so that appropriate psychosocial interventions can be offered.

Author Contributions

IB conducted the statistical analysis and contributed to writing the manuscript. DK contributed conceptually and to writing the manuscript. JD and ADS contributed to the conception of the study and to data collection. MH contributed to the conception of the study, to supervising the data collection, and to writing the manuscript. All authors read and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This study was possible through funding from the Fonds de recherche Québec-Santé (FRQS), also awarding the Principal Investigator (MH) a Senior Clinician-Scientist Salary Award. It was partially conducted as part of the Faculty of Medicine’s Summer Research Bursary Program, with JD supported by the Harold and Rhea Pugash Research Bursary and AS by the CIHR Health Professional Student Research Award, respectively.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received ethical approval from the McGill University Faculty of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Research and Ethics Committees (REC) at the recruiting hospitals (A08-B12-13B).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Canadian version of the Shame and Stigma Scale in Head and Neck Cancer

| |

Never |

Seldom |

Sometimes |

Often |

All the time |

| 1. I like my appearance |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 2. I avoid looking at myself in the mirror |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 3. I am ashamed of my appearance |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 4. I am happy with how my face or neck looks |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 5. I feel people stare at me |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 6. I avoid meeting people because of my looks |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 7. I enjoy going out in public |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 8. I am embarrassed when I tell people my diagnosis |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 9. I feel ashamed for having developed cancer |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 10. People avoid me because of my cancer |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 11. I have an urge to keep my cancer a secret |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 12. I sense that others feel strained when around me |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 13. I have a strong feeling of regret |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 14. I would do many things differently if given a second chance |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 15. I am embarrassed by the change in my voice |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 16. I avoid talking with others |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Subscales; Shame with Appearance: items 1-7; Sense of Stigma: items 8-12; Regret: items 13-14; Social/Speech concerns: items 15-16.

References

- Adams, R. J., Wu, M. L., & Wilson, M. (2012). The Rasch rating model and the disordered threshold controversy. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 72(4), 547-573. [CrossRef]

- Alias, A., & Henry, M. (2018). Psychosocial effects of head and neck cancer. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics, 30(4), 499-512. [CrossRef]

- Andrich, D., Sheridan, B., & Luo, G. (2011). RUMM2030 software and manuals. Perth, Australia: University of Western Australia. Available from http://www. rummlab. com. au.

- Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. Journal of psychosomatic research, 52(2), 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Bjordal, K., & Kaasa, S. (1995). Psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients 7-11 years after curative treatment. British Journal of Cancer, 71(3), 592-597. [CrossRef]

- Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2013). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. Psychology Press. [CrossRef]

- Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of personality and social psychology, 63(3), 452. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Zhang, Y., Cao, W., Hou, F., Xin, M., Guo, V. Y., Deng, Y., Wang, S., You, X., & Li, J. (2022). Preliminary validation of the Chinese version of the Shame and Stigma Scale among patients with facial disfigurement from nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLOS One, 17(12), e0279290. [CrossRef]

- Cash, T. F., Santos, M. T., & Williams, E. F. (2005). Coping with body-image threats and challenges: Validation of the Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory. Journal of psychosomatic research, 58(2), 190-199. [CrossRef]

- Cella, D. F., Tulsky, D. S., Gray, G., Sarafian, B., Linn, E., Bonomi, A., Silberman, M., Yellen, S. B., Winicour, P., & Brannon, J. (1993). The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol, 11(3), 570-579. [CrossRef]

- De Graeff, A., De Leeuw, J., Ros, W., Hordijk, G., Blijham, G., & Winnubst, J. (1999). A prospective study on quality of life of patients with cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx treated with surgery with or without radiotherapy. Oral oncology, 35(1), 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Dearing, R. L., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2005). On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive behaviors, 30(7), 1392-1404. [CrossRef]

- Devins, G. M. (2010). Using the illness intrusiveness ratings scale to understand health-related quality of life in chronic disease. Journal of psychosomatic research, 68(6), 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Devins, G. M., Binik, Y. M., Hutchinson, T. A., Hollomby, D. J., Barré, P. E., & Guttmann, R. D. (1984). The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: Importance of patients' perceptions of intrusiveness and control. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 13(4), 327-343. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P. M., & Magaletta, P. R. (2006). The short-form Buss-Perry Aggression questionnaire (BPAQ-SF) a validation study with federal offenders. Assessment, 13(3), 227-240.

- Dropkin, M. J. (2001). Anxiety, coping strategies, and coping behaviors in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer nursing, 24(2), 143-148. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M. A., Sterba, K. R., Brennan, E. A., Maurer, S., Hill, E. G., Day, T. A., & Graboyes, E. M. (2019). A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 160(6), 941-954. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D. G., & Fick, C. (1993). Measuring social desirability: Short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(2), 417-424. [CrossRef]

- Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466. [CrossRef]

- Gamba, A., Romano, M., Grosso, L. M., Tamburini, M., Cantú, G., Molinari, R., & Ventafridda, V. (1992). Psychosocial adjustment of patients surgically treated for head and neck cancer. Head & Neck, 14(3), 218-223. [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and schuster.

- Gonzalez, B. D., & Jacobsen, P. B. (2012). Depression in lung cancer patients: the role of perceived stigma. Psycho-Oncology, 21(3), 239-246. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A. K., Bakshi, J., Panda, N. K., Kapoor, R., Vir, D., Kumar, K., & Aneja, P. (2021). Assessment of Shame and Stigma in Head and Neck Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Henry, M., Albert, J. G., Frenkiel, S., Hier, M., Zeitouni, A., Kost, K., Mlynarek, A., Black, M., MacDonald, C., & Richardson, K. (2022). Body image concerns in patients with head and neck cancer: a longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, P., Fletcher, I., Lee, A., & Al Ghazal, S. (2001). A body image scale for use with cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer, 37(2), 189-197. [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D. W., Patel, S. G., Baser, R. E., Bell, R., Farberov, M., Ostroff, J. S., Li, Y., Singh, B., Kraus, D. H., & Shah, J. P. (2012). Preliminary evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Shame and Stigma Scale in head and neck cancer. Head & Neck. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H., Block. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic review, 58(3), 419-438.

- Linacre, J. M. (1994). „Sample Size and Item Calibration Stability “, Rasch Measurement Transactions, 7 (4), 328. URL: http:// www. rasch. org/ rmt/ rmt74m. htm.

- Linacre, J. M. (2002). Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. Journal of Applied Measurement, 3(1), 85-106.

- Linacre, J. M. (2004). Rasch model estimation: Further topics. Journal of Applied Measurement, 5(1), 95-110.

- List, M. A., D'Antonio, L. L., Cella, D. F., Siston, A., Mumby, P., Haraf, D., & Vokes, E. (1996). The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy-head and neck scale: a study of utility and validity. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society, 77(11), 2294-2301.

- Marais, I., & Andrich, D. (2008). Formalizing dimension and response violations of local independence in the unidimensional Rasch model. J Appl Meas, 9(3), 200-215.

- Masters, G. N. (1982). A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika, 47(2), 149-174. [CrossRef]

- Melissant, H. C., Jansen, F., Eerenstein, S., Cuijpers, P., Laan, E., Lissenberg-Witte, B. I., Schuit, A. S., Sherman, K. A., Leemans, C. R., & Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. (2021). Body image distress in head and neck cancer patients: what are we looking at? Supportive Care in Cancer, 29, 2161-2169.

- Ostroff, J. S., Jacobsen, P. B., Moadel, A. B., Spiro, R. H., Shah, J. P., Strong, E. W., Kraus, D. H., & Schantz, S. P. (1995). Prevalence and predictors of continued tobacco use after treatment of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer, 75(2), 569-576.

- Pallant, J. F., & Tennant, A. (2007). An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: an example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Pruyn, J., De Jong, P., Bosman, L., Van Poppel, J., van Den Borne, H., Ryckman, R., & De Meij, K. (1986). Psychosocial aspects of head and neck cancer–a review of the literature. Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences, 11(6), 469-474.

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385-401.

- Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and achievement tests. Danish Institute for Educational Research.

- Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of clinical psychology, 38(1), 119-125.

- Rhoten, B. A., Murphy, B., & Ridner, S. H. (2013). Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral oncology, 49(8), 753-760. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A. M., Frenkiel, S., Desroches, J., De Simone, A., Chiocchio, F., MacDonald, C., Black, M., Zeitouni, A., Hier, M., Kost, K., Mlynarek, A., Bolster-Foucault, C., Rosberger, Z., & Henry, M. (2019). Development and validation of the McGill body image concerns scale for use in head and neck oncology (MBIS-HNC): A mixed-methods approach. Psycho-Oncology, 28(1), 116-121. [CrossRef]

- Shunmuga Sundaram, C., Dhillon, H. M., Butow, P. N., Sundaresan, P., & Rutherford, C. (2019). A systematic review of body image measures for people diagnosed with head and neck cancer (HNC). Supportive Care in Cancer, 27, 3657-3666. [CrossRef]

-

Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. S: TX.

- Tam, T. (2019). Addressing stigma: Towards a more inclusive health system (Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www. canada. ca/conte nt/dam/phac-aspc/docum ents/corpo rate/publi catio ns/chief-publi chealt h-offic er-repor ts-state-publi c-healt h-canad a/addre ssing-stig m a-what-we-heard/stigm a-eng. pdf, Issue.

- Tennant, A., & Conaghan, P. G. (2007). The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Care & Research, 57(8), 1358-1362. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.-T., Lee, Y., Hung, C.-F., Lin, P.-Y., Chien, C.-Y., Chuang, H.-C., Fang, F.-M., Li, S.-H., Huang, T.-L., & Chong, M.-Y. (2019). Validation of the Chinese Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Management and Research, 11, 10297-10305.

- Vallerand, R. J. (1989). Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 30(4), 662. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Azman, N., Eyu, H. T., Jaafar, N. R. N., Sahimi, H. M. S., Yunus, M. R. M., Shariff, N. M., Hami, R., Mansor, N. S., & Lu, P. (2022). Validation of the Malay Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale among Cancer Patients in Malaysia. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(21), 14266. [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361-370.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).