1. Introduction

In modern society, patients have higher demands for esthetic restorations and that induced faster evolution of dental materials. Teeth appearance is emotional sensitive, influences patients’ self-awareness and other people’s perception and reactions. Restorations, apart from esthetic and functional rehabilitation, should allow performing good oral hygiene, without causing any kind of discomfort for patients, allergies or tissue irritations. On the other hand, their optical properties have to match those of dental tissues and maintain during time and the influence of intraoral environment. Advanced technologies contribute to constant improvement of material physical, chemical, biological and esthetic characteristics, but very important aspect is their changes in time, material fatigue and aging [

1]. In vitro studies have to be done before those materials get to the dental market, but in vivo studies are necessary to evaluate how materials perform in real clinical conditions, under occlusal loading, their interaction with hard and soft tissues and potential complications, that can occur during function.

In everyday practice doctors are facing increased number of patients, who are diagnosed with bruxism or other forms of mandibular parafunctional activity. They have higher intensity and longer lasting masticatory forces causing higher risk for complications, compared to patients without signs and symptoms of parafunction. These cases are challenging for prosthodontic therapy because parafunctions may induce faster wear, damage, fracture and other changes of restoration with antagonistic teeth wear, especially in the presence of restorations made of materials featuring higher hardness than tooth enamel or dentin. The most common consequences are loss of hard teeth tissue, flattening occlusion surface, occurrence of abrasive facets, teeth hypersensitivity, headaches, tension, discomfort or pain caused by muscle spasms, masticatory muscle tiredness, problems with periodontal tissue, excessive tooth mobility and temporomandibular joint disfunction, poor sleep quality [

2]. After prosthodontic rehabilitation of patients with parafunctions, the harmful effect of masticatory forces most often reflects as wear of acrylic teeth, denture and ceramic fractures in PFM or full ceramic restorations, complications with implant system components: implant, abutment, suprastructure, screws, implant supported mobile/fixed or hybrid restorations [

3]. Regarding all these facts, material selection could be one of the key factors for successful treatment of patients with parafunctions.

For a long time, PFM crowns were the golden standard for fixed restorations [

4,

5], but current trend are ceramic systems and new metal-free composite materials with different compositions of monomer and filler [

5], such as High-Performance Polymer BioHPP (Bredent, GmbH & Co.KG, Senden, Germany), which was one of the first presented hybrid material, combining advantages of two worlds, composite and ceramic. It consists of linear polycyclic aromatic thermoplastic polymer based on polyether ether ketone (PEEK) which is furthermore strengthened with 20% of ceramic particles (0.3-0.5 µm). BioHPP is biocompatible class 2a medical device, that has potential for wide range of applications, such as removable or fixed restorations (crowns, bridge, telescopic crowns, implant abutments and suprastructures). It is considered that BioHPP® has shock-absorbing effect, modulus of elasticity similar to bone (4GPa), flexural strength (>150 MPa), low specific weight, high fracture resistance (Stawarczuk et al.), low water absorption and solubility, radiotransparency, wear protection of opposing teeth. These biological and mechanical properties make BioHPP® suitable for restorative material and beneficial especially for prosthodontic treatment of patients with CMD.

This article aimed to address the outcome of prosthodontic rehabilitation of patients with parafunctional activities, when thermoplastic material based on PEEK, as a restorative material was used.

2. Material and method

The research was conducted as a prospective clinical study at the Clinic for prosthodontics, approved by Ethical committee of Faculty of Dental Medicine, University of Belgrade.

All patients were informed about this clinical study, signed written consent and filled up a questionnaire about general and oral health status, signs and symptoms of parafunctions. Patients’ selection was based on anamnestic findings, clinical examination, and radiological status using OPT x-ray imaging.

Inclusion criteria:

Signs and symptoms of parafunctional activities

Partial edentulism on one or both sides (missing 1 or 2 teeth) in the posterior region of the maxilla or mandible.

No teeth missing in the opposing dentition (natural teeth, PFM or ceramic restorations).

Good general health, motivated, willing to cooperate with acceptable oral hygiene.

Exclusion criteria:

Presence of infection, endodontically or periodontally non-treated teeth

Compromised general health, radiotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy, chronic, osseous, metabolic, or malign illness

Positive anamnestic data for alcohol and drugs abuse, or psychiatric treated patients

Presence of neurological illnesses that can cause myoclonic activities of the lower jaw

Patients with poor oral hygiene and uncooperative.

According to selection criteria, 22 patients were included, 30 bridges (100 units) were made, half of them had natural teeth in the opposite jaw and the other half with PFM or ceramic dental restorations as antagonistic dentition. Fourteen patients (63,6%) with partial edentulism on one side, while the other eight (36,4%) were treated with fixed partial dentures (FPD) on both sides. After tooth preparations, impressions were taken with standard metal trays, one stage technique using A-silicone (Elite® HD+, Zhermack SpA, Rovigo, Italy). Bridges were made of thermoplastic polymer based on PEEK (BioHPP, ”for 2 press”, Bredent medical GmbH & Co.KG, Senden, Germany) and veneered using nanohybrid composite (Visio.lign veneering system, Bredent medical GmbH&Co., Senden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Before cementation, fitting, occlusion and interdental contacts were checked and then the inner side was sandblasted using Al2O3 particles (110 µm) under the pressure of 2-3 bars. After that, the inner side was treated with light curing primer (visio.link PMMA & Composite Primer, Bredent medical GmbH & Co., Senden, Germany) and polymerized for 90sec (M+W Superlite power pen, Dental Müller und Weygandt, GmbH, Büdigen, Germany). Teeth were etched using 37% orthophosphoric acid for 15sec, and after rinsing and drying, coated using Adhese® Universal (Ivoclar Vivadent Inc., NY, USA) for 20sec and light cured 10sec. After cementation (Variolink® Esthetic LC, Ivoclar Vivadent Inc., NY, USA) occlusal contacts were checked, if needed reoccluded and polished. Three follow-ups were performed, immediately after cementation, after six and twelve months, postcementation. The relevant clinical data, photodocumentation and interventions during one year of monitoring, were recorded for each patient.

2.1. Spectrophotometry

Color parameters changes (L*, a*, b*) were measured using spectrophotometer VITA Easyshade® Advance 4.0 (VITA, Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany), based on the CIELAB system. Standardized measurements were performed using a silicone key (Elite Transparent, Zhermack SpA, Badia Polesine, Italy) on the middle third of the buccal surface of the mesial pontic, on the wet and dry tooth.

L* for lightness, with 0 being a perfect black, with 0% reflectance or transmission. A rating of 50% indicates a middle gray, while 100% indicates a perfect white.

a* represents redness-greyness of the color, positive values are red, while negative values are green, a level of 0 is neutral.

b* denotes yellow-blueness of the color, yellow for (+) values and blue for (-) b* values.

The color change defined as the colorimetric difference (ΔE), represents the differences between L*, a*, and b* values of reference and measured sample [

1,

6]. Lower ΔE figures indicate greater accuracy, while high ΔE indicates a significant mismatch. In recent literature reviews, it is recommended that ΔE=1 is the limit value up to which color difference is not visually detectable and ΔE=2.7 is a threshold to perceive color difference, that is clinically acceptable. When ΔE≤2.7, color changes match the level of acceptance 50:50%, which means that 50% of observers consider the color difference acceptable [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

2.2. Periodontal indices

Plaque Index (PI) according to Silness-Löe and Calculus Surface Index (CSI) by Ennever, were used to examine the adhesiveness of material and plaque accumulation on vestibular, oral, mesial and distal surface. Assessment of periodontal tissue condition was performed using Gingival Index (GI) according to Silness-Löe and Bleeding On Probing (BOP) according to Ainamo & Bay. Graded periodontal probes (North Carolina Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) were used according to well-known methodology for indices scoring.

2.3. Clinical FDI criteria for the evaluation of direct and indirect restorations

The final treatment outcome was graded according to

FDI criteria (World Dental Federation). Clinician that was performing scoring went through an online course using e-calib program (

www.e-calib.info) [

12,

13]. Scoring included assessment of esthetic, functional and biological characteristics of FPD. In the group of esthetic parameters, surface luster, staining (surface, margin), color matching, translucency and esthetic anatomical form, were monitored. Fracture of material, marginal adaptation, retention, approximal surface (contour, contact points/food impaction) and patient’s satisfaction were evaluated in the functional properties group. Biological parameters reflected periodontal response, adjacent mucosa, oral and general health. From the original version, parameters that did not correspond to the study goals, were excluded and total of ten FDI criteria were included. Restorations were evaluated and the highest grade of esthetic, functional and biological criteria, was used as overall score for that group. Those 3 scores, one for each group, were compared and the highest grade was used as the final score:

Grade 1, clinically excellent/very good: restoration fulfills all criteria, healthy periodontal tissues;

Grade 2 classified as good when one or more criteria differ from ideal values. Restoration could be slightly corrected without risk of compromising integrity of teeth or adjacent tissue, corrections not mandatory;

Grade 3, satisfactory: restoration has some imperfections, but quality is still acceptable; Imperfections cannot be eliminated without damaging teeth or adjacent mucosa, due to extension or localization;

Grade 4, clinically unsatisfactory, relative failure: quality of restoration is not acceptable and corrections are mandatory;

Grade 5, clinically poor, presents absolute failure with severe or acute periodontitis and restoration must be replaced with a new one.

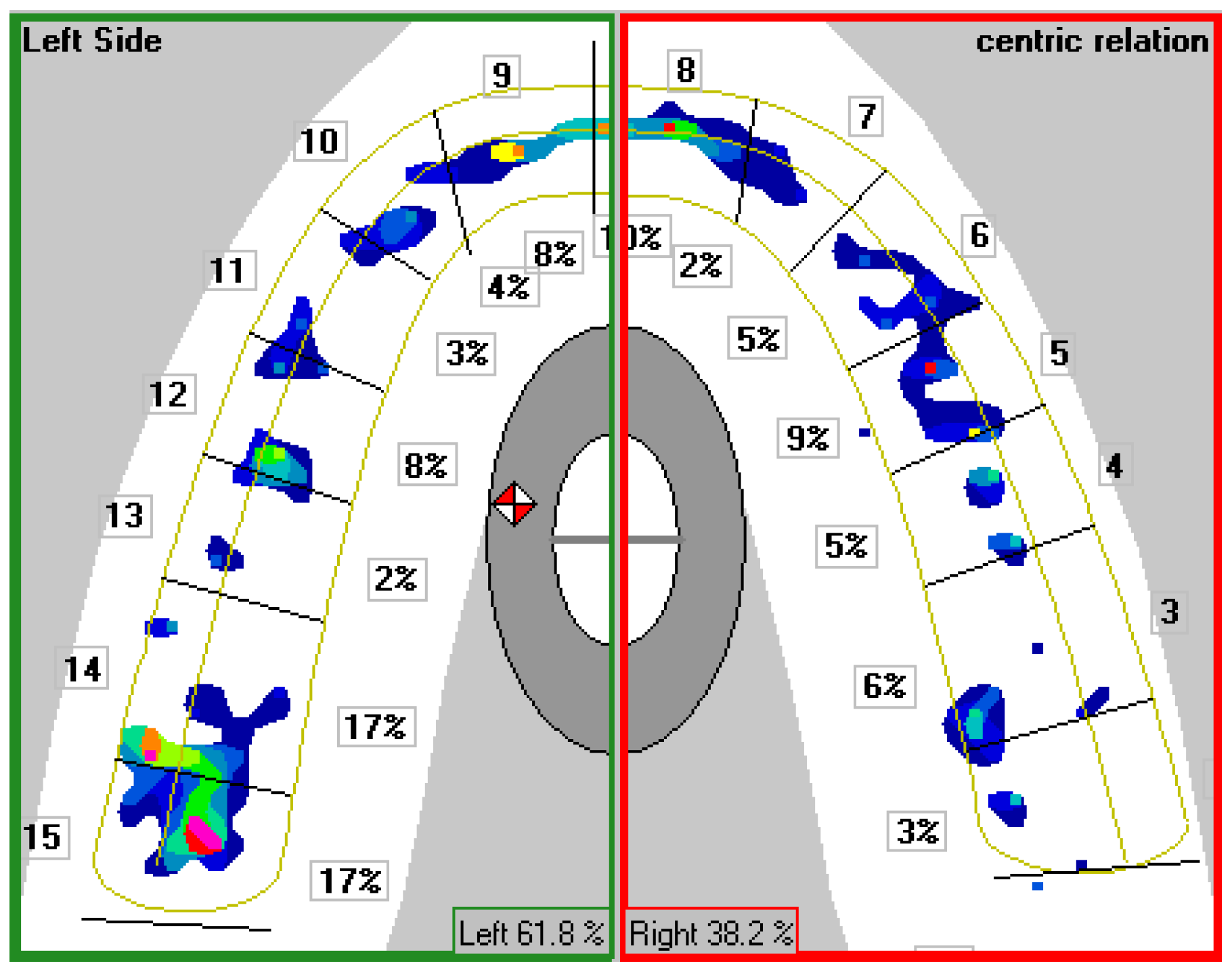

2.4. Occlusal analysis

Clinical and computer analysis of occlusal contacts were performed after cementation and on recalls. Conventional occlusal registration in central occlusion (CO) and during eccentric movements of the lower jaw, were performed using articulating paper 40 µm thick (Arti-Check® micro-thin, Bausch, Köln, Germany). Computer occlusal analysis was performed using T-Scan

TM III system ver. 7.0 (Tekscan, Boston, USA). To minimize risk for errors, patients were trained to move the lower jaw to the position of maximum intercuspation and the device was calibrated by selecting the corresponding jaw width, according to central incisor width. Adjusting sensor sensitivity in regards to individual bite force made it possible to differ relative forces of closing in CO from other occlusal contacts. Relative forces were graphically shown using different colors, from the low intensity (black/blue), medium (green/yellow), to the highest forces (orange/red). Number, distribution, intensity and surface of occlusal contacts were presented on two-dimensional occlusograms with fourteen fields, matching antagonistic teeth pairs (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional occlusogram of T -ScanTM III system.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional occlusogram of T -ScanTM III system.

Center of Occlusal Forces (COF) and its distance from the middle of the dental arch was illustrated with a red-white icon (approximately 31mm distal from the incisors on the midsagittal plane), and represented a spot where occlusal forces were balanced in antero-posterior and mid-sagittal direction. Using statistical analysis of COF in a population with “normal” occlusion, during CO, two elliptic fields derived. A bigger ellipse limits the probability that COF is located inside with a 95% chance, and a smaller ellipse with a chance of 68%. Dislocations of COF from the center of elliptic fields, means irregular force distribution, with uneven and higher occlusal load on individual or teeth groups, on one or both sides of the dental arch [

14].

Occlusal time (OT)- time of establishing occlusal contacts, was measured from first contact until the moment when all teeth were in CO. OT should be 0.2 – 0.3seconds, when occlusal forces are balanced, a longer time indicates the presence of premature contacts and slower positioning of the lower jaw in CO.

2.5. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)

Patient-reported outcomes are important for understanding whether treatment procedures make a difference to patients’ health status and quality of life, providing insight on the effectiveness of therapy from the patient’s perspective. OHIP-49 (Oral Health Impact Profile) is one of the most sophisticated questionnaires for evaluating the quality of life related to oral health (OHRQoL), designed to allow patient’s subjective impressions on dysfunction, discomfort, and disability, caused by stomatognathic system condition. It consists of 49 questions divided into 7 groups: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, social disability, hendicap. Answers were evaluated using Lickert’s scale but in reverse order, so that higher scores reflected the higher impact of problems and worse oral health (0 – never, 1 – almost never, 2 – sometimes, 3 – often, 4 – very often). In this research, an adapted version in the Croatian language OHIP-CRO49 [

15] was used. The validity, reliability and applicability of OHIP-49 was confirmed through Petričević research [

16]. Patients filled up a questionnaire two times, once before treatment and again at the end of the observation period. Also, the effect size of therapy, for patients with parafunctions, was determined according to Cohen, an effect size of 0.2 considered small, 0.5 medium and over 0.8 a large effect.

2.6. Registration of complications during and after prosthodontic therapy

Problems and complications related to teeth preparation procedure, cementation technique, intraoral defects repair and polishing of FPD were recorded. At every follow-up complications were clinically checked: cracks, wear, chipping or delamination of veneering material, substructure fractures and wear of opposing natural teeth or crowns.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive, analytic parametric (t-test, ANOVA) and nonparametric statistics ( Hi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, Friedman test, Wilcoxon test, Cochrane Q test, McNemar test) were performed.

3. Results

3.1. Spectrophotometry results

During this research, a statistically significant difference in color change in the first six months between dry and wet surface was noticed, while there were different values between six and twelve months, but without statistically significance. Total color change ΔE, during one year was statistically significantly higher when it was measured on a wet surface. Almost all bridges after 1-year of function, experienced changes for L*, a*, b* color parameters,

Table 1. After one year, the color change of the veneering composite was within 50:50% acceptability threshold, in 36.7% of the cases when the color was measured on a dry surface and only 20%, when the measurements were done on wet crown surface,

Table 1. Color change was identified as visible for 90% restorations.

Table 1.

Composite material color change in accordance to acceptance level 50:50%.

Table 1.

Composite material color change in accordance to acceptance level 50:50%.

| |

Acceptable color change |

Unacceptable color change |

| N |

% |

N |

% |

| ΔE0-6 dry tooth acceptance level |

5 |

16.7% |

25 |

83.3% |

| ΔE6-12 dry tooth acceptance level |

9 |

30.0% |

21 |

70.0% |

| ΔE0-12 dry tooth acceptance level |

11 |

36.7% |

19 |

63.3% |

| ΔE0-6 wet tooth acceptance level |

3 |

10.0% |

27 |

90.0% |

| ΔE6-12 wet tooth acceptance level |

7 |

23.3% |

23 |

76.7% |

| ΔE0-12 wet tooth acceptance level |

6 |

20.0% |

24 |

80.0% |

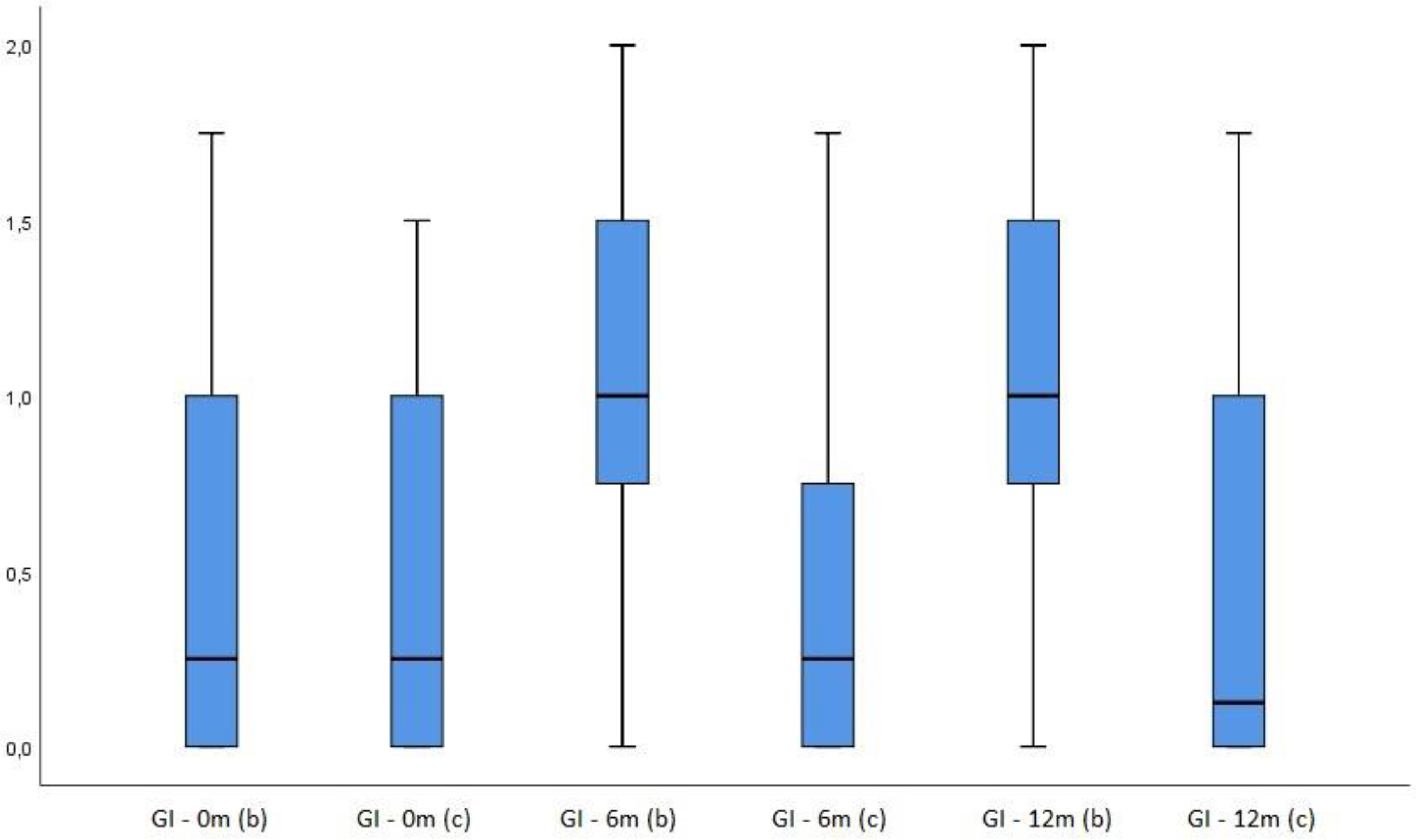

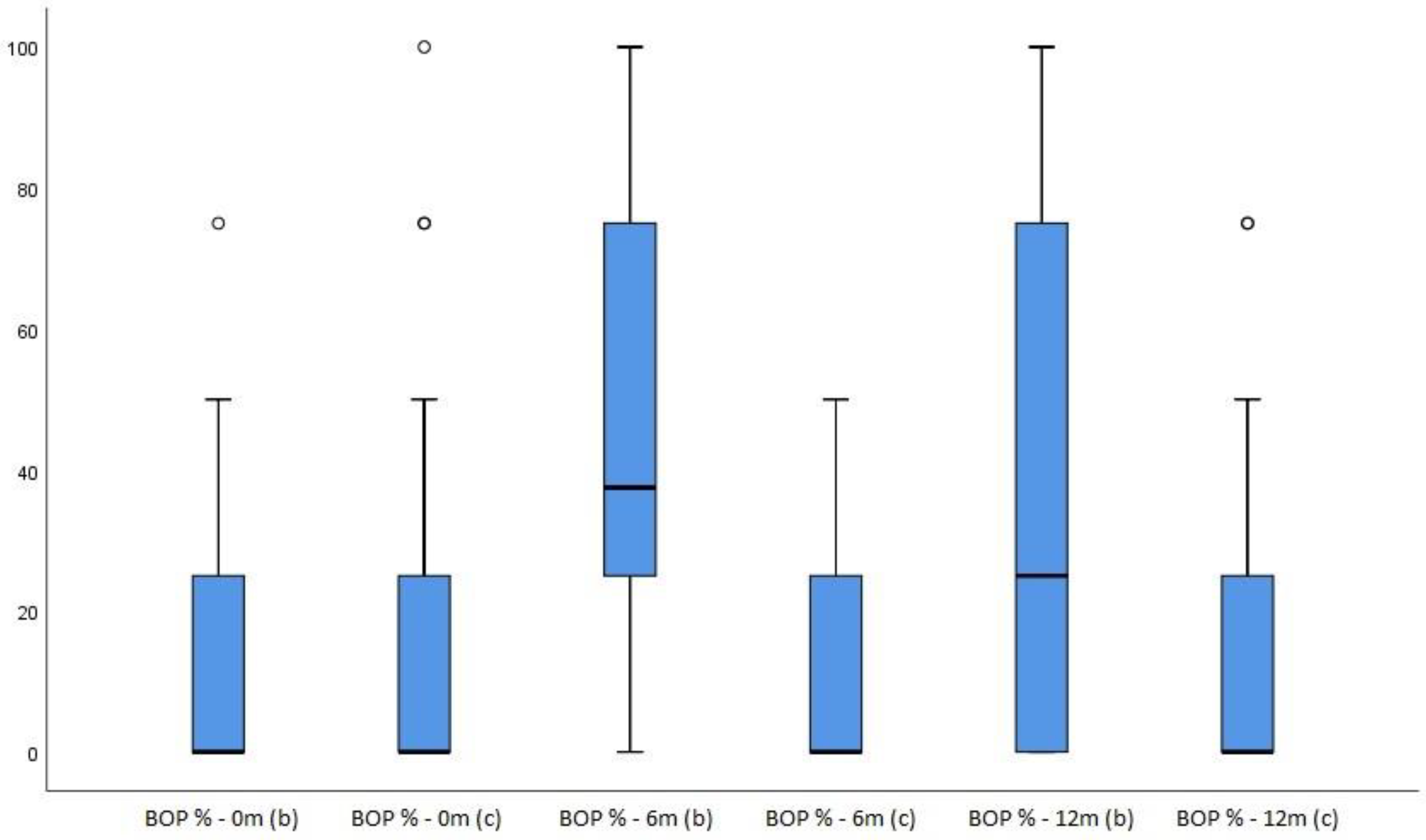

3.2. Periodontal indices

At the level of the entire dental arch, Plaque and Gingival Index values distribution using the Friedman test, did not show a statistically significant difference between three measuring times (p=0.093 for PI; p=0,351 for GI), as well as between the first and the last (PI p=0.351; GI p=0.122). CSI values were highest after twelve and lowest after six months. Using the Friedman test, there were no statistically significant differences between first, second and third measurement. Analyzing BOP index, there was no statistically significant difference between all three measurements (Friedman test, p=0,120) or between the first and third (p=0.421), although BOP values were higher after six months.

PI measured at the mesial abutment tooth before therapy, after six and twelve months were compared with a PI of the mesial agonist tooth. Wilcoxon Signed ranks test showed that there was no statistically significant difference between measurements at the beginning (p=0.519), but there was a statistically significant difference at six (p<0.001) and twelve months measurements (p=0.002). Higher values were observed at the restored tooth vs the control (not restored) tooth. Comparing CSI, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test showed that there was no statistically significant difference for all three measuring times (0m p=0.655, 6m p=0.157, 12m p=0.317). GI- analysis, using the Friedman test, demonstrated no statistically significant difference between measurements on the control tooth at all three times (p=0.913), but there was a statistically significant difference for the bridge GI at six (p<0.001) and twelve months measurement (p<0.001) compared to the first one (p=0.083),

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Gingival Index of bridge (b) and control tooth (c) (before, 6 months after therapy, 12 months after therapy).

Figure 2.

Gingival Index of bridge (b) and control tooth (c) (before, 6 months after therapy, 12 months after therapy).

BOP index analysis, using the Friedman test demonstrated a statistically significant difference between all three times (p<0.001), with the increase in values after six and twelve months, while there was no statistically significant difference for the control tooth (p=0.282). Comparative analysis of BOP values between the bridge and control tooth for each time point, showed that there is no statistically significant difference at zero point (p=0.272), but there is a statistically significant difference after six (p<0.001) and twelve months (p=0.001),

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

BOP index of bridge (b) and control tooth (c) (before therapy, after 6 and after 12 months).

Figure 3.

BOP index of bridge (b) and control tooth (c) (before therapy, after 6 and after 12 months).

3.3. Results of restoration evaluation according to FDI criteria

The distribution of scores, shown in

Table 2, demonstrated only grades 1, 2 and 3, for esthetic and biological parameters. Concerning functional performance, four bridges received grade 4, which caused that 13.3% of all restorations were defined as not acceptable. According to FDI criteria, restorations were divided into two groups, acceptable (grades 1, 2, 3) and not acceptable (grades 4 and 5) and their distribution is shown in

Table 3. Esthetical and biological acceptance for FPD was 100% after 6 and 12 months.

Table 2.

Distribution of restorations according to FDI criteria.

Table 2.

Distribution of restorations according to FDI criteria.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

p value* |

| N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

| Esthetical 6.m |

17 |

56.7% |

13 |

43.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0,058 |

| Esthetical 12.m |

13 |

43.3% |

15 |

50.0% |

2 |

6.7% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Functional 6.m |

20 |

66.7% |

4 |

13.3% |

4 |

13.3% |

2 |

6.7% |

0,416 |

| Functional 12.m |

20 |

66.7% |

1 |

3.3% |

5 |

16.7% |

4 |

13.3% |

| Biological 6.m |

9 |

30.0% |

13 |

43.3% |

8 |

26.7% |

0 |

0.0% |

0,068 |

| Biological 12.m |

11 |

36.7% |

18 |

60.0% |

1 |

3.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Total FDI 6.m |

4 |

13.3% |

16 |

53.3% |

8 |

26.7% |

2 |

6.7% |

0,166 |

| Total FDI 12.m |

1 |

3.3% |

18 |

60.0% |

7 |

23.3% |

4 |

13.3% |

Table 3.

Restoration acceptance according to FDI criteria.

Table 3.

Restoration acceptance according to FDI criteria.

| |

Acceptable charachteristics |

Unacceptable charachteristics |

| N |

% |

N |

% |

| Esthetical 6.m |

30 |

100.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Esthetical 12.m |

30 |

100.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Functional 6.m |

28 |

93.3% |

2 |

6.7% |

| Functional 12.m |

26 |

86.7.0% |

4 |

13.3% |

| Biological 6.m |

30 |

100.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Biological 12.m |

30 |

100.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Total FDI 6.m |

28 |

93.3% |

2 |

6.7% |

| Total FDI 12.m |

26 |

86.7.0% |

4 |

13.3% |

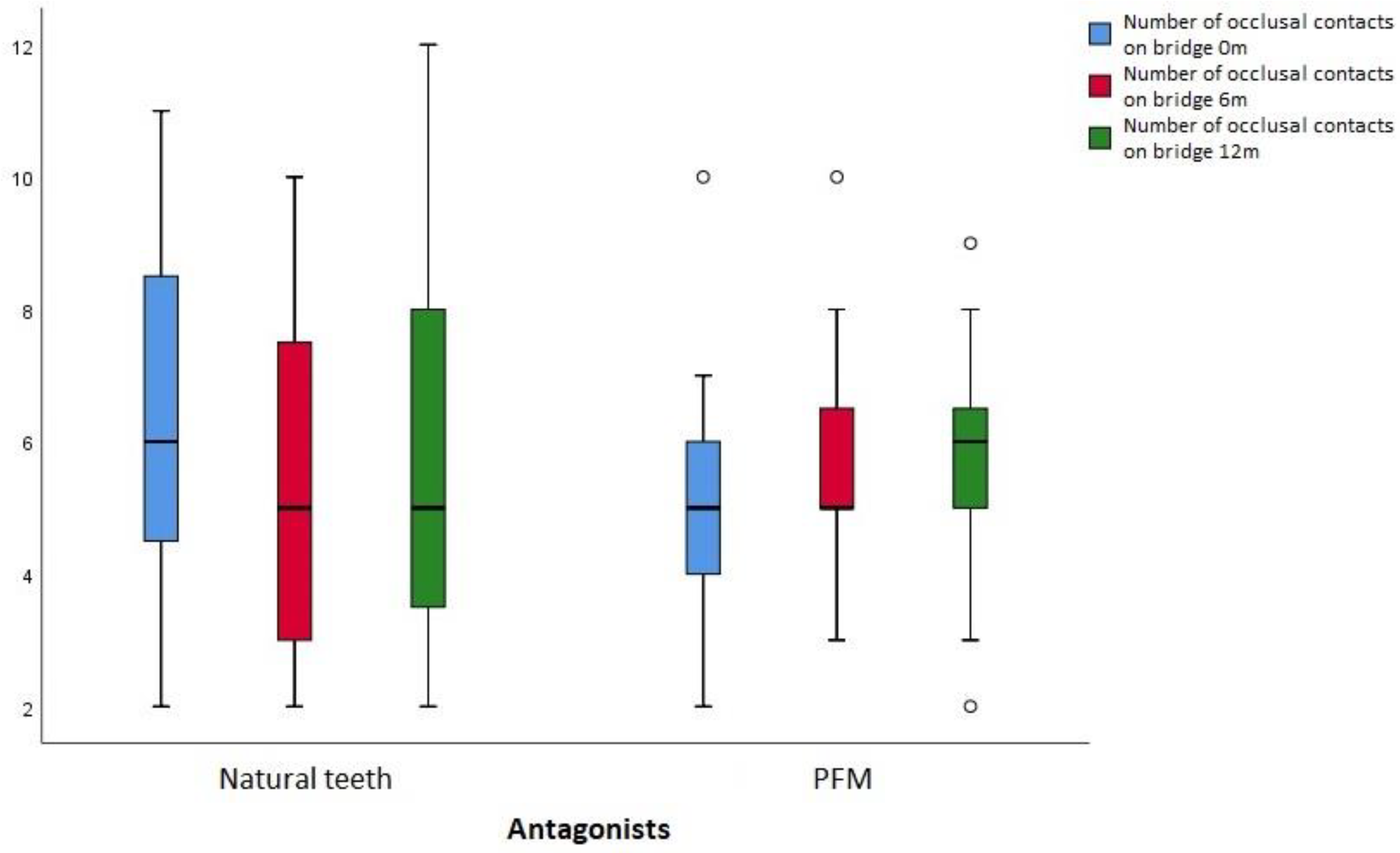

3.3. Results of occlusal contacts analysis

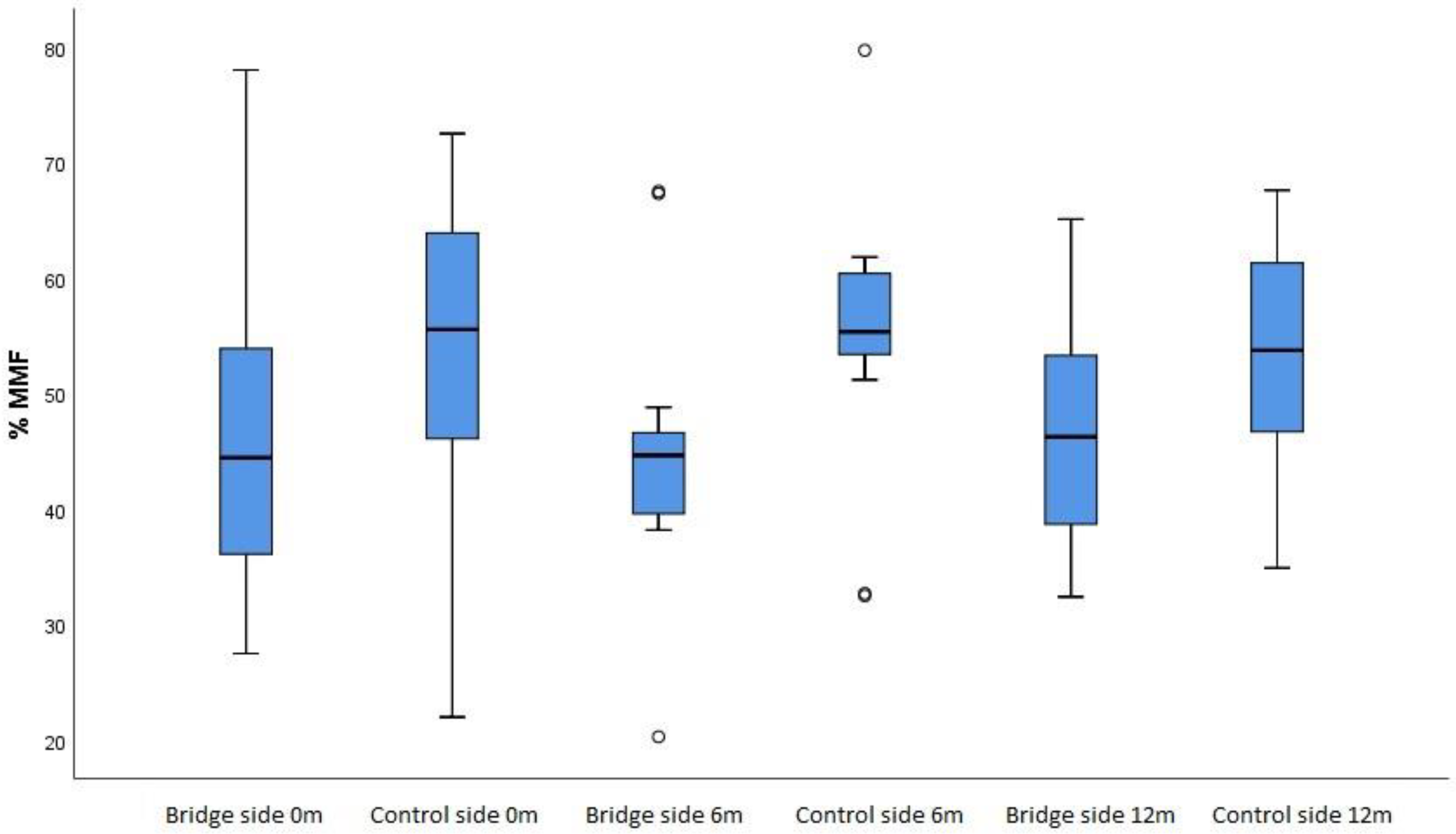

Analyzing a number of contacts on side of the arch where restoration was done and on the other side, no statistically significant difference was found between all three measurements, for the side where restoration was done (p=0.629), as well as, for the other side (p=0.248). A number of occlusal contacts was higher on the restored (table 5.26) compared to control lateral side. That difference was statistically significant, using Wilcoxon’s test, after therapy (p=0.002), after six (p=0.001) and twelve months (p=0.003),

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Number of occlusal contacts on restored and control side, at 0, 6 and 12 months.

Figure 4.

Number of occlusal contacts on restored and control side, at 0, 6 and 12 months.

The number of contacts were also analyzed according to the type of antagonists, natural teeth or PFM/ceramic restorations. Statistical analysis presented uniform results with no statistically significant difference in the number of contacts (0m p=0.106; 6m p=0.941; 12m p=0.675) between different type of antagonists,

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Number of occlusal contacts on restored side with antagonistic natural teeth or PFM restoration at 0, 6 and 12 months.

Figure 5.

Number of occlusal contacts on restored side with antagonistic natural teeth or PFM restoration at 0, 6 and 12 months.

Distribution of occlusal contacts using Wilcoxon’s test showed that there was statistically significant difference between the number of contacts on anterior and posterior teeth at every measurement (0m p=0.004, 6m p<0.001, 12m p<0.001), but constant in time, with no significant difference between measurements.

Values for relative occlusal forces were lower on the side with FPD, but using the t-test there was no statistically significant difference on both sides (0m p=0.418, 6m p=0.129, 12m p=0.238), table 4. Using the Friedman test, no statistically significant difference was found for anterior teeth in all three measuring times (p=0.804) and for posterior teeth (p=0.804). It was evident that there was a difference in values of relative forces between anterior and posterior teeth, using Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test, at zero (p=0.001), sixth (p<0.001) and twelfth month point (p<0.01),

Figure 6.

Table 4.

Relative forces on restored and control side before rehabilitation, 6 and 12 months after prosthetic restoration.

Table 4.

Relative forces on restored and control side before rehabilitation, 6 and 12 months after prosthetic restoration.

| Relative bite force on |

N |

A.S. |

SD |

Median |

Perc. 25 |

Perc. 75 |

| Restored side 0.m |

14 |

46.67 |

14.90 |

44.45 |

36.10 |

53.90 |

| Restored side 6.m |

14 |

44.91 |

11.76 |

44.65 |

39.60 |

46.60 |

| Restored side 12.m |

14 |

46.81 |

9.65 |

46.25 |

38.70 |

53.30 |

| Control side 0.m |

14 |

53.33 |

14.90 |

55.55 |

46.10 |

63.90 |

| Control side 6.m |

14 |

55.09 |

11.76 |

55.35 |

53.40 |

60.40 |

| Control side 12.m |

14 |

53.19 |

9.65 |

53.75 |

46.70 |

61.30 |

Figure 6.

Relative bite force on restored and on control side before, after 6 and after 12 months.

Figure 6.

Relative bite force on restored and on control side before, after 6 and after 12 months.

The COF position on occlusogram,

Table 5, presented no statistically significant difference in bridges distributions, after cementation and twelve months after (McNemar-Bowker test, p=0.392). COF distance from the arch middle, at zero time point Med= 17.60mm and six months Med= 15.40mm was very similar, but a difference was evident and statistically significant between the first and the third measurement, Med= 12.10 (t=2.641; p=0.015).

Table 5.

Position of Center of Occlusion in relation to center of jaws before, after 6 and after 12 months.

Table 5.

Position of Center of Occlusion in relation to center of jaws before, after 6 and after 12 months.

| |

White area |

Grey area |

Outside of areas |

| COF 0.m |

N |

3 |

11 |

8 |

| % |

13,6% |

50,0% |

36,4% |

| COF 6.m |

N |

3 |

13 |

6 |

| % |

13,6% |

59,1% |

27,3% |

| COF 12.m |

N |

6 |

11 |

5 |

| % |

27,3% |

50,0% |

22,7% |

Descriptive statistics of occlusal contacts time, according to Friedman test revealed no statistically significant difference between all three measurements (p=0.635). After prosthodontic therapy 59.1% cases had acceptable OT, t≤ 0.3s, after 12-months 45.5%., but without statistically significant difference (Cohran test Q =0.889; p=0.641).

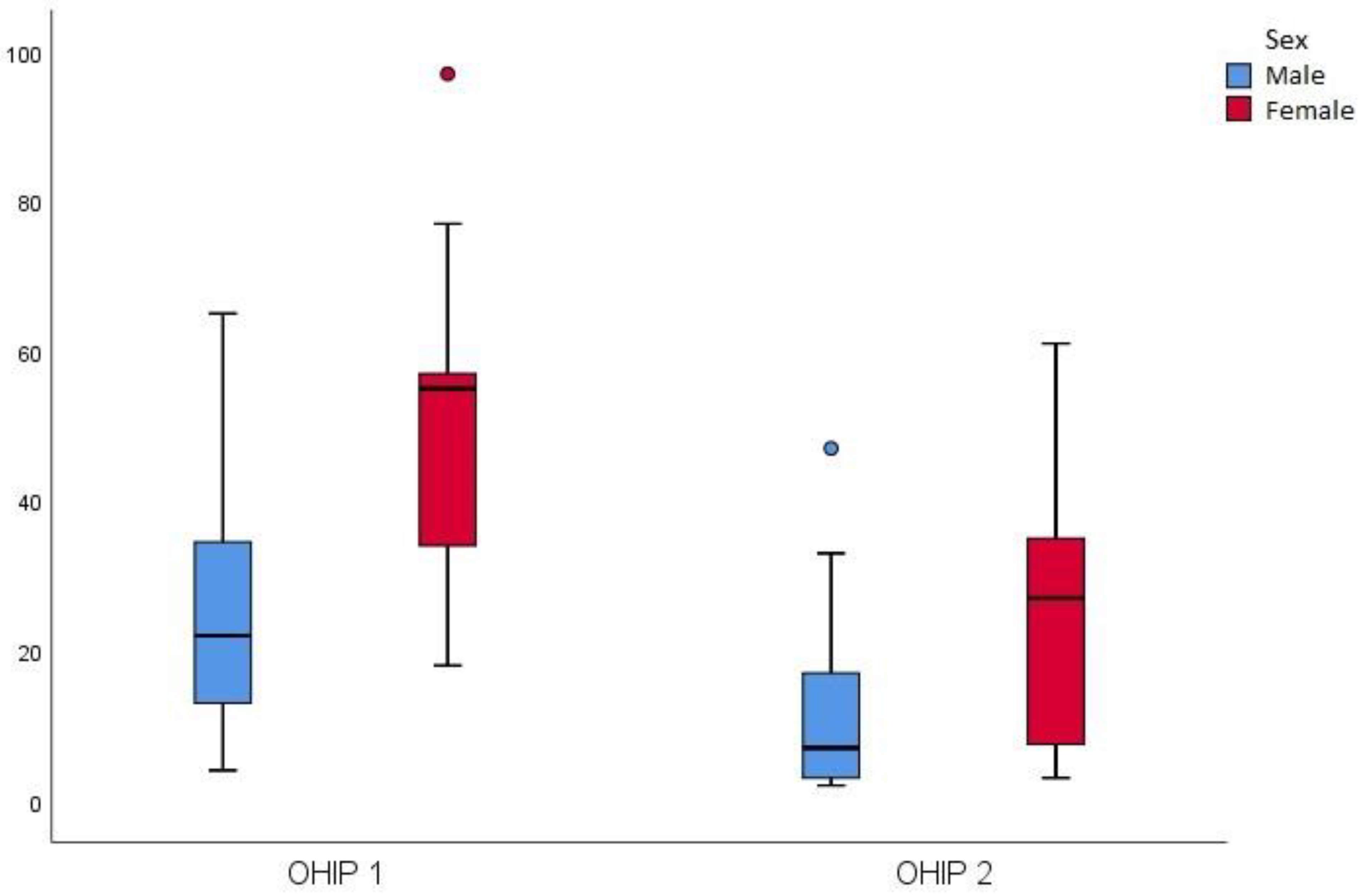

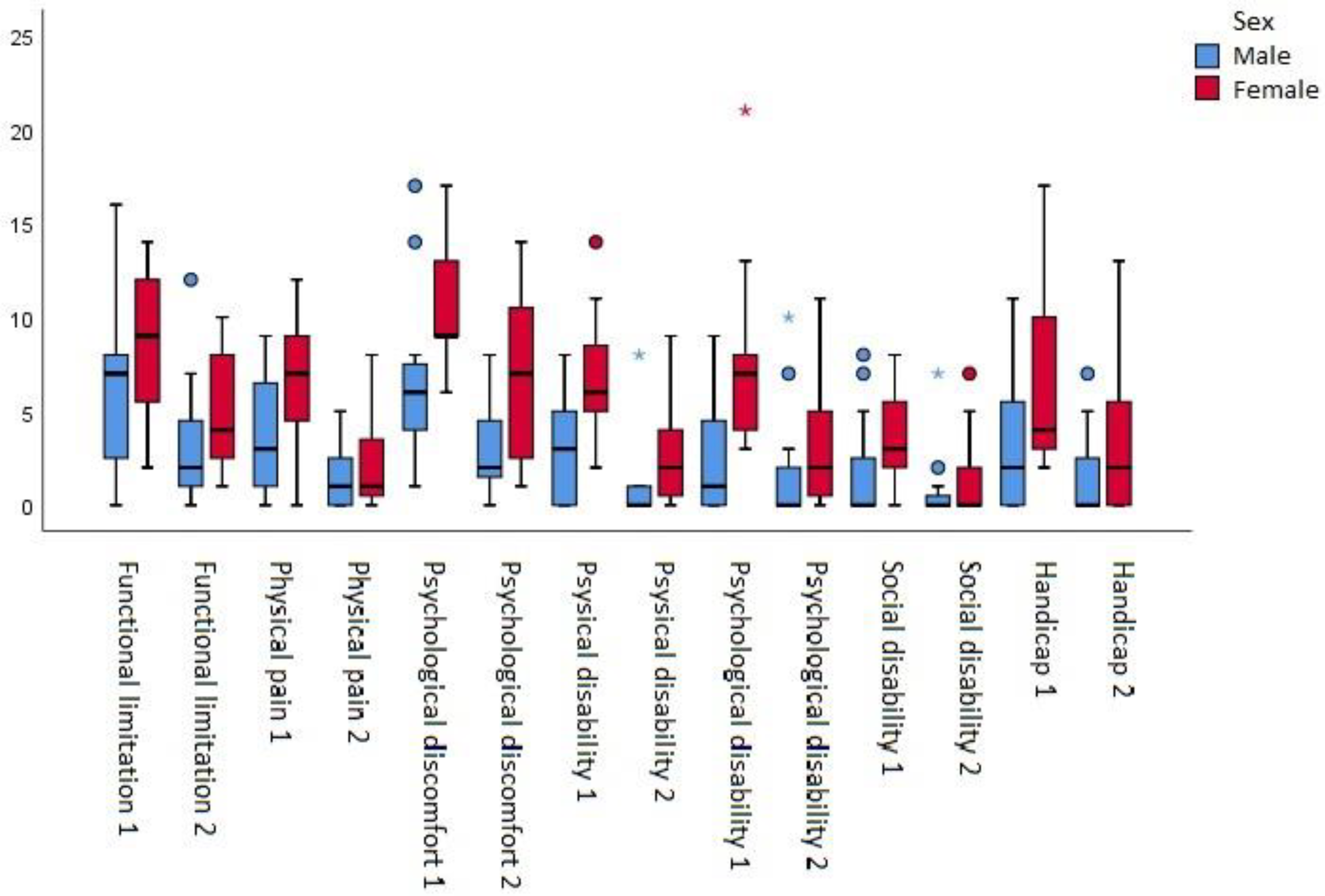

3.3. OHIP-49 questionnaire results

Descriptive statistics of the number of points in each question group and the total number of points of OHIP-49 (

Figure 7), before and after rehabilitation, using Wilcoxon’s test, confirmed that all differences were statistically significant. It was observed that there was a significant drop in values for almost all parameters for both sexes, but more evident for women and for those parameters: pain, discomfort, mental disability (

Figure 8). The effect size of the therapy was high (Cohen’s d 0.89).

Figure 7.

Total number of OHIP-49 points, sex based, before and after prosthetic therapy.

Figure 7.

Total number of OHIP-49 points, sex based, before and after prosthetic therapy.

Figure 8.

OHIP-49 numbers by groups, sex based, before and after therapy.

Figure 8.

OHIP-49 numbers by groups, sex based, before and after therapy.

3.3. Results of clinical findings during and after rehabilitation

As for complication, cusps chipping of veneering material had incidence 6.7 % , delamination 10%, clinically visible wear 30% for bridges, after 1-year of function and corrections as occlusal adjustments, polishing or intraoral reparation, were indicated and done in 22.7% of the cases. No framework fractures, wear or damages of opposing dentition were observed during one year. Patients reported mild tooth sensitivity in 31.8% and some difficulties during oral hygiene maintenance in 27.3%, loss of retention with repeated cementation in 18.2% of bridges, more frequent for 4-unit than 3-unit bridges. Two patients had minor functional complaints during mastication.

4. Discussion

Patients, 11 male and 11 female, average age 43.2±10.4, with good general health and confirmed parafunctional activities were included in study. Questionnaires are often used in researches and clinical practice, but their limitations is subjectivity of collected data [

17,

18]. Analyzing data from our questionnaire, the impression was that most patients were not aware of the parafunctional acctivities that is similar to Carlsson and Magnusson (2000) conclusions that only 10-20% of patients were aware of night bruxism, while the other 20% noticed the presence of parafunctions during the day [

19]. A positive answer to the question if someone suggested that they grind teeth during sleep, gave 7 study participants (31.8%), while 36.4% had a bad habit of biting foreign objects. More than half (54.5%) had unilateral chewing, which can be considered a bad habit, that can contribute to daily parafunctions [

19]. Almost half (45.5%) subjects had pain in the neck and shoulder muscles. Seven patients (31.8%) had teeth sensitivity after waking up. Limited mouth opening, fatigue during speech or chewing was present in 13.6% of the cases.

4.1. Discussion of spectrophotometry results

Composite materials have excellent esthetic properties which is why they are the most often used materials in restorative dentistry, but insufficient color stability often affects long-term patients’ satisfaction and can be the reason for partial or complete replacement of restoration [8. 9]. Measurements in the study, conducted on a wet and a dry surface to mimic intraoral conditions, have confirmed that results differ and depend on the method used for color determination. Changes in color parameters were greater when measured on a wet surface. Considering the threshold of perception 50:50%, color change after 1 year, was not noticeable, more than 50% of observers have not noticed a color change, only 1/10 bridges. When color was measured on a dry surface, more than 1/3 of bridges had clinically acceptable color change (ΔE≤2.7). When color was measured on the wet surface, 1/5 of bridges was clinically acceptable. In the oral cavity, restorative materials are exposed to the influence of saliva, food, drinks and medicines [

20,

21] which leads to the adsorption or absorption of pigments. The degree of material discoloration depends on eating habits, smoking and oral hygiene level [

21]. Some mouthwashes, frequently used, can also affect the color change of composite materials. If deeper layers are not affected, discolorations can be removed by polishing [

21]. Material properties, manufacturing process, surface roughness and oral environment factors are crucial for color stability. During this research, the statistically significant difference in color, was noticed after 6 months and after 1 year, on both wet and dry surface, even though none of the study participants noticed the color change, nor complained about its esthetic appearance, which can be explained by the fact that restorations were located in the posterior region.

4.1. Discussion of periodontal indices

It is well-known that periodontal tissue health is prerequisite for long term success of prosthodontic treatment. The impact that FPD had on surrounding tissues, plaque adherence and status of oral tissues, were evaluated by measuring periodontal indices before prosthodontic rehabilitation, 6 and 12 months after. When the restoration’s surface, due to material properties, is more adherent for plaque, it is difficult to maintain good oral hygiene. Values of periodontal indices suggest a possible correlation between the presence of restoration and the status of surrounding tissues. Results of PI, CSI, GI, and BOP index showed that there were no statistically significant differences in the periodontal status of patients between measurements. However, comparing periodontal tissue around restored tooth, after 6 and 12 months, with the control tooth, there was an increase in values of PI. There was no difference before therapy, so change is a consequence of restoration presence. PI reflects the current status, if the patient has brushed his teeth before the examination, PI values would be lower. Therefor GI and BOP values were more reliable and they were statistically significantly higher around restored teeth on follow ups, compared with control teeth. At the first measurement, before prosthodontic rehabilitation, there was no difference, which implies that FPD could be responsible for gingival inflammation.

According to the results of some other researches [

4,

22,

23], periodontal tissue response is influenced by many factors, in the case of examined material, surface smoothness maybe the most dominant factor. This fact emphasizes necessity to include polishing procedure in regular follow-ups, among patient training, education and motivation to perform proper oral hygiene and maintenance in general. The constant presence of microorganisms, especially from subgingival dental plaque, is a source of bacterial antigens that deplete the defense system and promote development of a pathological process in the periodontal tissue, which is why care must be taken at every step of clinical and dental lab work. Inadequate restorations (material selection, subgingivally extended or oversized, marginal leakage, bad occlusion) or clinical procedures (preparation, impression, temporarisation, cementation) could harm periodontal tissue and compromise the treatment outcome.

4.1. Discussion evaluation according to FDI criteria

FDI Scoring has become very popular for comprehensive evaluation of success criteria in clinical investigations. Findings from this study confirmed that FDI scoring represents good attempt to standardize comparison of therapy results. It does not explain the causes of prosthetic failures, material-, patient- or doctor-related, but gives useful information where complications more often occur during clinical practice.

In this study FPDs achieved better results for esthetical and biological parameters, compared to functional. According to aesthetic characteristics at six-month control, all restorations were scored as acceptable, 17 (56.7%) with grade 1 and the rest of them (43.3%) got grade 2. At twelve month control, 13 (43.3%) were clinically excellent, 15 (50%) good, and 2 restorations (6.7%) got a grade 3. Color, translucency and anatomic form deviation, were parameters responsible for lower esthetic grades. Regarding functional properties, after 6 months, 28 restorations were acceptable (93.3%) and 66.7% got the highest grade. Four patients complained for having difficulties in maintaining oral hygiene and those restorations got a grade (2). Also, four FPD (13.3%) got grade (3) for the presence of crack lines and/or chipping in veneering material. Two FPD (6.7%) were considered not acceptable, grade (4) and were repaired. At twelve months control, 26 restorations (86.7%) were acceptable, 20 (67.7%) with grade (1), only one restoration (3.3%) grade (2) and five restorations (16.7%) got grade (3). Four not acceptable FPDs, had larger defects (13.3%) and required correction. On the final check-up, all restorations had acceptable biological characteristics, 11 (36.7%) had grade (1), 18 of them (60%) grade (2), only one (3.3%) got grade (3) due to plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation.

4.1. Discussion of occlusal contacts analysis

Prosthodontic rehabilitation of patients with parafunctions is complex and involves changing the occlusal morphology, the contact relationship of the teeth and/or the position of the mandible for therapeutic purposes [

14]. In everyday clinical practice, the most common method for identifying and analyzing occlusal contacts includes the use of articulation papers and doctor and patient subjective interpretation about the strength and time of the establishment occlusal contacts [

24]. Thanks to the mechanoreceptors in the periodontal ligament, particles with a thickness of 10-100 µm can be registered, which is why the articulating papers should be as thin as possible, preferably 8-20 µm [

25,

26,

27]. Occlusal markers provide limited and questionable results, however the computerized method of occlusion analysis enables more objective, precise and reliable recording of the number, distribution and intensity of real occlusal contacts [

24].

The average number of contacts during all three measurements was 16-18 and in accordance with the research of Garcia et al. [

28]. The number of contacts on the anterior and posterior teeth did not change over time, with a statistically significant difference between the anterior and posterior teeth, which is also in agreement with earlier studies [

29,

30]. Occlusal balancing, as well as wear of the veneering composite material on the restored side of dental arch, had not affected the change of occlusal relations or compromised existing occlusal scheme. In order to prove whether there is an abrasive effect of the restorative material on the opposing natural or restored tooth and vice versa, it is necessary to analyze the number and distribution of occlusal contacts over a longer time period.

The total relative force was expressed as a percentage of the maximum bite force (%MMF - Max Movie Force), at the moment when the jaw reaches the position of maximum intercuspation [

31]. In this study, with the patient head in an upright position, statistically significantly difference of MMF values (0-12m: 98.16-98.39%) was not registered between measurements. The relative force distribution was not significantly different between the right and the left side of the dental arch and did not change significantly over time. Statistically significant difference for MMF, between the anterior and posterior teeth was confirmed, over 75% of the load was distributed in the area of the posterior teeth, as expected.

The clinical importance of COF registration is in detection of premature contacts and the location of excessive occlusal forces. Distance of the icon, which represents the "balance point" did not differ statistically significant between measurements, but after one year, the average distance was about 4 mm shorter and COF was closer to the middle of the dental arch. Although without a statistically significant difference, after one year the number of patients in whom the position of the icon was inside the smaller white field increased (27.1% of patients), while the number of patients with icon inside the gray field remained unchanged (50%). Compared to the initial measurement, in five patients (22.7%) the position of the icon was still unsatisfying, outside the gray and white fields. The change in the icon position determined during this research, indicated that the occlusion has been improved in some cases, but for other patients still indicated an excessive load and occlusal imbalance.

One of the main goals of occlusal therapy is achieving simultaneous occlusal contacts [

32]. The time that elapses from the first to the last occlusal contact should be 0 seconds, up to 0.3sec is considered acceptable, while longer than 0.3sec indicates the presence of occlusal interferences [

24]. According to the results of this research, there was no statistically significant difference in the occlusal time, after cementing the bridges, after 6- and 12- months. Further analyses revealed that only seven patients (31.8%) had an acceptable time during all three measurements. In two patients (9.1%) after occlusal adjustments there was time reduction. Despite occlusal balancing, after one year five patients (22.7%) had occlusal time longer than 0.3seconds. The reason was most likely the existence of occlusal disorders that were not related to the presence of fixed restoration. As the T-Scan device has the ability to measure the bite very precisely, even very small deviations can be registered, which do not necessarily have to be a consequence of the existence occlusal interferences. Computer analysis significantly contributes to the assessment of occlusal relations and provides more precise establishment of even and simultaneous occlusal contacts, but requires good training and understanding, both by the doctor and by the patient. It is generally accepted that balanced occlusion is mayor aspect for the longevity of dental restorations. Occlusal disharmony plays a significant role in load distribution on the tissues of orofacial system, in persons with parafunctional activities [

33]. This research confirmed advantages of T-Scan system in monitoring the changes of the occlusal complex in patients with parafunctions, with the suggestion to analyze several consecutive bites, to eliminate possible errors due to improper bite and to use full potential of T-Scan system in diagnostics and therapy.

4.1. Discussion of OHIP-49 questionnaire results

Within the limited number of patients in this study, a significant difference was observed in the total number of OHIP points, before and after prosthodontic therapy for all participants, also recognized in earlier studies [

16]. The results showed that there is a statistically significant difference for all examined parameters before and after therapy, which means that there was an improvement in the quality of life for the patients with parafunctions. Higher values of the OHIP number of points, indicates worse OHRQoL. The biggest change in the number of OHIP points was presented in the group of physical pain, mental discomfort and disability in women. A greater decrease of total OHIP points, after treatment in femail group, supports the claim that for women, oral health has more significant effect on life quality. Mc Grath and Bedi (2000) consider that poor oral health is significantly more likely to cause pain, discomfort and financial costs for women and solving oral health problems leads to improved mood, appearance, and general well-being [

34].

The best method for interpretation differences in OHIP scores before and after treatment is using effect size. The effect of therapy, according to Cohen, in the scope of this research was high 0.89, which proves that therapy was successful and had positive effect on the quality of life for patients with parafunctional activities. In this study, the total number of OHIP points after treatment was 19.41, higher compared to the results of other studies, most likely because persons with parafunctions are more prone to stress and self-criticism and oral health affects their quality of life to a greater extent [

16,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. It has been proven that oral disorders have a greater impact on young people, people with compromised general health, as well as people with a worse economic and social status [

40,

41]. Eliminating pain, restoring function and esthetics through conservative or prosthodontic therapy, leads to improved oral health, better social integration and performance of daily activities. Some authors suggest that PROM, patient’s evaluation and impressions of therapy is equally important when making conclusions about its success, as is the application of clinical indicators [

42]. Clinical studies generally examine certain aspects of therapy and monitor changes that occur over time, while neglecting the psychosocial component and the patient’s satisfaction with restorations. The results of this research confirmed that oral rehabilitation is very important for patients with parafunctions. Also experience and evaluation of the therapy outcome, could be conditioned by individual personality characteristics.

4.1. Discussion of clinical findings during and after rehabilitation

FPDs, 100 crowns in total, were analyzed in order to more precisely determine the predilection places for defects when patients have parafunctional problems. During the follow-up period, marginal integrity and proximal interdental contacts were not compromised. Cracks in veneering material were noticed on three 3-unit bridges (10%) in lower jaw: on two bridges at six-month and on one bridge at twelve-month control. Crack lines were located on the vestibular side of pontic near occlusal surface and in one case on the buccal ridge of mesiobuccal cusp of abutment tooth. This could be a consequence of uneven distribution of occlusal forces and overload during bruxism episodes. Inspecting occlusal surfaces of restoration and mesial agonist, comparing photographs of bridges after cementation, wear of veneering material was noticed as abrasion facets and cusps flattening on 16% of the crowns, within four 3-unit and five 4-unit bridges, at six-month control examination. After occlusal adjustment, there was no wear progression at twelve-month follow up which relate to results of experimental study, done by Špadijer et al. (2019) [

43]. The general opinion of the patients was that they easily got used to the restoration, the chewing sensation did not differ from natural teeth and they were comfortable during functions. At the final inspection, chipping was observed on lingual cusps of two pontic crowns (2%) and delamination, as separation of the veneer material from the PEEK-substructure, occurred on three bridges. Exactly 3% of the crowns, had delaminations on distal tooth abutment, in the transitional zone occluso-buccal and occluso-distal surface. Findings from this research support the fact that the type of defects determines different location. All damages were repaired in the patient’s mouth directly. Clinical examination showed no wear of the hard dental tissues or the ceramic material of the opposing teeth after one year, which goes in favor for application of the tested material in prosthodontic rehabilitation of patients with parafunctions. To make the most of the material properties, it is obligatory to follow the clinical protocol and the manufacturer’s recommendations. Appropriate restoration design and accurate analysis of occlusal contacts are critical to reduce risk of complications.

In this study, problems related to the tooth preparation were mostly the result of reduced interocclusal space due to tooth wear. The problem occurred in cases where increase in VDO (vertical occlusal dimension) was not indicated or only one side needed to be restored. To ensure optimal 2 mm for the interocclusal space and proper material thickness, occlusal reduction leaded to short tooth abutment with insufficient retentive form, thin layer of veneering material and higher risk for complications. There was no accidental pulp perforation during preparation, seven patients (31.8%) reported transitory sensitivity after bridge cementation. Placing pearls on the vestibular surfaces, according to the manufacturer’s recommendation to improve the retention of the veneering layer, demanded more invasive preparation or crowns appeared oversized and less esthetically pleasing.

Protocol for adhesive cementation was applied, regarding the fact that PEEK material have no light transmission and only dual-curing composite cements are usable. Bonding agent should be applied in a thin layer, to avoid incorrect placement of the restoration. Incomplete seating and occlusal interferences, registered in some patients were the results of the teeth preparation and cementation procedure. During observation period, four patients (18.2%) had bridges de-bonded, with the composite cement remaining inside the restoration. Insufficient bond strength between dentin and luting agent is generally a problem in adhesive cementation and clinical guidelines should be followed.

The possibility of intraoral repair is considered to be one of the main advantages of using PEEK veneered with composite material. The reparation involves repeating all steps during the veneering procedure in dental lab, sandblasting of the restoration surface, coating with a suitable primer and applying composite layer. Intraoral sandblasting is challenging and different approaches to roughen the surface with carbide burs do not give satisfactory results, while the use of diamond burs leads to thermal damage of the material surface. During this study, intraoral reparation was successfully performed in five patients (22.7%).

It is important to polish the crown surface to a high gloss, after occlusal adjustment or damage repair, to obtain surface integrity and smoothness, that would not promote plaque and bacterial adhesion, discoloration and/or inflammation of surrounding tissues. During research, six patients (27.3%) reported soft and hard deposits on crowns and difficulties maintaining hygiene, which indicates the importance of polishing procedure.

In the literature, there is still insufficient data on failure rate for FPD, made of PEEK framework veneered with composite material. The research results indicate that the weakest link is the composite and it’s bonding with substructure, so that further research should address monolithic restorations for patients with parafunctions.

5. Conclusion

Spectrophotometry showed changes of color parameters for FPDs, based on PEEK veneered with composite, after 1-year in oral environment. Discoloration at six and twelve months recall was above the 50:50% acceptability threshold for most physician-evaluated restorations, but with no clinical significance for patients.

Results of periodontal indices revealed a greater accumulation of plaque and gingival inflammation around bridges, compared to the control teeth, at the six- and twelve-month follow-up examinations.

According to evaluation based on the FDI criteria, prosthodontic therapy with FPD made of tested material can be considered successful.

Based on the results of the computer analysis of occlusion, no significant difference was observed in the number of occlusal contacts and the intensity of relative forces on the restored and control sides of the dental arch, as well as, on the anterior and posterior teeth, after six and twelve months of functional loading. Type of antagonist had no influence on the distribution of occlusal contacts and forces in the area of FPDs.

All participants involved in this study were satisfied with treatment outcome. The results of the OHIP-49 questionnaire, after prosthodontic rehabilitation, showed an improvement in the quality of life associated with oral health, whereby the positive impact of the therapy was more pronounced in female subjects.

During the one-year observation period, excessive occlusal loading, caused by parafunctional activities led to complications: cracks, delamination, chipping and wear of the veneering composite matherial that appeared in a limited number of cases. All damages were repaired intraorally and were not accompanied by change in the occlusal morphology of the antagonist teeth. Complications during and after therapy may appear as a consequence of the insufficient retentive design of prepared teeth, unbalanced occlusion, the impossibility of controlling the amount of applied bond/primer during adhesive cementation, inadequate surface treatment for damage repair and underestimate importance of polishing procedure.

It can be concluded that further improvements and defining protocols for optimal clinical and dental lab procedures should be taken into consideration. Long-term clinical trials are necessary to analyze performance of PEEK material and its comparison with similar hybrid or ceramic restorative materials, especially in challenging cases, for patients with CMD and in implant therapy.

Contribution

Aleksandra Špadijer Gostović: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review and Editing; Aleksandar Racić: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft; Aleksandar Todorović: Resources; Aleksandra Čairović: Data Curation, Investigation; Mirjana Perić: Methodology, Data Curration; Ivana Jakovljević: Methodology, Data Curation, Investigation, Formal Analysis; Katarina Radović: Resources.

Formatting of funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bredent medical GmbH & Co.KG for providing testing material.

Conflicts of Interests

No conflict of interests has been declared.

References

- Gawriolek M, Sikorska E, Ferreira LFV, Costa AI, Khmelinskii I, Krawczyk A, Sikorski M, Koczorowski R. Color and luminescence stability of selected dental materials in vitro. J Prosthodont. 2012;21: 112-22. [CrossRef]

- Lazić V. Definicije i istorijat bruksizma. U: Lazić V, Rudolf R. Bruksizam- škripanje zubima u spavanju. Belgrade: Faculty of Dental Medicine; 2008. pp. 13-6.

- Lobezoo F, Brouwers JEIG, Cune MS, Naeije M. Dental implants in patients with bruxing habits. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33: 152-9. [CrossRef]

- Dautović-Kazazaić L, Redţepagić S, Ajanović M, Gavranović A, Strujić S. Evaluacija parodontalnog stanja kod pacijenata nositelja metal-keramičkih i metal-akrilatnih krunica u razdoblju od jedne do pet godina. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2010; 44(1):34-46.

- Ohlmann B, Dreyhaupt J, Schmitter M, Gabbert O, Hassel A, Rammelsberg P. Clinical performance of posterior metal-free polymer crowns with and without fiber reinforcement: one-year results of a randomised clinical trial. J Dent. 2006; 34(10):757-62. [CrossRef]

- Stamenković D, Todorović A. Boja u stomatologiji. U: Stamenković D i sar. Stomatološki materijali, knjiga 2. Belgrade: Faculty of Dental Medicine; 2012. pp. 155-80.

- Chu SJ, Trushkowsky RD, Paravina RD. Dental color matching instruments and systems. Review of clinical and research aspects. J Dent. 2010; 38(Suppl 2):e2-16. [CrossRef]

- Trifkovic B, Powers JM, Paravina RD. Color adjustment potential of resin composites. Clin Oral Invest. 2018; 22:1601-7. [CrossRef]

- Sabatini C, Campillo M, Aref J. Color stability of ten resin-based restorative materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012; 24:185-99. [CrossRef]

- Barutcigil Ç, Yildiz M. Intrinsic and extrinsic discoloration of dimethacrylate and silorane based composites. J Dent. 2012;40(Suppl 1):e57-63. [CrossRef]

- Perez MM, Ghinea R, Ugarte-Alvan Laura I., Pulgar R, Paravina RD. Color and translucency in silorane-based resin composite compared to universal and nanofilled composites. J Dent. 2010;38:e110-6. [CrossRef]

- Hickel R, Roulet JF, Bayne S, Heintze SD, Mjör IA, Peters M, Rousson V, Randall R, Schmalz G, Tyas M, Vanherle G. Recommendations for conducting controlled clinical studies of dental restorative materials. Clin Oral Invest. 2007;11:5-33. [CrossRef]

- Hickel R, Peschke A, Tyas M, Mjör I, Bayne S, Peters M, Hiller KA, Randall R, Vanherle G, Heintze SD. FDI World Dental Federation: clinical criteria for the evaluation of direct and indirect restorations-update and clinical examples. Clin Oral Invest. 2010;14:349-66. [CrossRef]

- Lazić V, Ţivković S, Popović G. Kompjuterska analiza okluzije T- Scan II sistemom. Serbian Dental J. 2004;51:24-9.

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1417-32. [CrossRef]

- Petričević N. Procjena činitelja uspješnosti mobilno-protetske terapije u pacijenata s različitim protetskim radovima. Zagreb: Stomatološki fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu; 2009.

- Shetty S, Pitti V, Babu CLS, Kumar GPS, Deepthi BC. Bruxism: A Literature Review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010;10(3):141-8. [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo F, Visscher CM, Ahlberg J, Manfredini D. Bruxism and genetics: a review of the literature. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(9):709-14. [CrossRef]

- Lazić V. Etiologija i epidemiologija bruksizma. U: Lazić V, Rudolf R. Bruksizam- škripanje zubima u spavanju. Belgrade: Faculty of Dental Medicine; 2008. pp. 19-27.

- Bagheri R, Burrow MF, Tyas M. Influence of food-simulating solutions and surface finish on susceptibility to staining of aesthetic restorative materials. J Dent. 2005;33:389-98. [CrossRef]

- Arocha MA, Mayoral JR, Lefever D, Mercade M, Basilio J, Roig M. Color stability of siloranes versus methacrylate-based composites after immersion in staining solutions. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:1481-7.

- Sirajuddin S, Narasappa KM, Gundapaneni V, Chungkham S, Walikar AS. Iatrogenic Damage to Periodontium by Restorative Treatment Procedures: An Overview. Open Dent J. 2015;9(Suppl 1:M11):217-22. [CrossRef]

- Knoernschild KL, Campbell SD. Periodontal tissue responses after insertion of artificial crowns and fixed partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;84:492-8. [CrossRef]

- Todorović A. Analiza okluzije u pacijenata sa fiksnim zubnim nadoknadama na implantatima primenom kompjutera. Belgrade: Faculty of Dental Medicine; 2012.

- Kazemi M, Geramipanah F, Negahdari R, Rakhshan V. Active tactile sensibility of single-tooth implants versus natural dentition: a split-mouth double-blind randomized clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2014;16(6):947-55.

- Carossa S, Lojacono A, Schierano G, Pera P. Evaluation of occlusal contacts in the dental laboratory: influence of strip thickness and operator experience. Int J Prosthodont. 2000;13:201-4.

- Halperin GC, Halperin AR, Norkling BK. Thickness, strenght and plastic deformation of occlusal registration strips. J Prosthet Dent. 1982;48(5):575-8.

- García VCG, Cartagena AG, Sequeros OG. Evaluation ofocclusal contacts in maximum intercuspation using the T-Scan system. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24:899-903.

- Cartagena AG, Sequeros OG, García VCG. Analysis of two methods for occlusal contact registration with the T-Scan system. J Oral Rehabil. 1996;24:426-32.

- Mannes WL, Podoloff R. Distribution of occlusal contacts in maximum intercuspation. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;62:238-242.

- Tekscan T-Scan® User Manual (Rev L) https://www.scribd.com/document/307954685/TScan-User-Manual.

- Babu RR, Nayar SV. Occlusion indicators: A review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2007;7(4):170-4. [CrossRef]

- Lazic V, Todorović A, Ţivković S, Martinović Ţ. Kompjuterska analiza okluzije kod osoba sa bruksizmom. Belgrade; Srpski Arhiv za Celokupno Lekarstvo. 2006;134:22-9.

- McGrath C, Bedi R. Gender variation in the social impact of oral health. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2000;46:87-91.

- Shetty S, Pitti V, Babu CLS, Kumar GPS, Deepthi BC. Bruxism: A Literature Review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010;10(3):141-8. [CrossRef]

- Kampe T, Edman G, Bader G, Tagdae T, karlsson S. Personality traits in a group of subjects with long-standing bruxing behaviour. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24:588-93. [CrossRef]

- Ohayon MM, Li KK, Guilleminault C. Risk factors for sleep bruxism in the general population. Chest. 2001;119(1):53-61. [CrossRef]

- Major M, Rompré PH, Guitard F, Tenbokum L, O’Connor K, Nielsen T, et al. Acontrolled daytime challenge of motor performance and vigilance in sleep bruxers. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1754-62.

- Bayar GR, Tutuncu R, Acikel C. Psychopathological profile of patients with different forms of bruxism. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:305-11. [CrossRef]

- Jenei Á, Sándor J, Hegedűs C, Bágyi K, Nagy L, Kiss C, Szabó G, Márton IJ. Oral healthrelated quality of life after prosthetic rehabilitation: a longitudinal study with the OHIP questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:99-106. [CrossRef]

- Locker D, Slade G. Association between clinical and subjective indicators of oral health status in an older adult population. Gerodontology. 1994;11:108-14. [CrossRef]

- Feine JS, Awad MA, Lund JP. The impact of patient preference on the design and interpretation of clinical trials. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:70-4.

- Jakovljevic IV, Todorovic A, Budak I, Sokac M, Milicic B, Gostovic AS. Measurement of dental crown wear -In vitro study. Dent Mater J. 2020 Jan 31;39(1):126-134. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2018-280. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).