Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1.1. Background

- Shift from traditional to specialty drug products

- Growth in pharmacist’s involvement in reimbursed disease management services

- Automation of pharmacy and gradual extinction of traditional dispensing roles

- Transformation of pharmacies into healthy living centers

- Continuing growth of the digital health enterprise

- Rise of analytical pharmacy to test each batch of dispensed medication

1.2. Objectives

Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Analysis

- Mail-order and medical supply service (use of common carriers to deliver goods)

- Specialty pharmacy distributor (low volume/high cost/specialized delivery or administration)

- Compounding pharmacy (combining/mixing/altering ingredients tailored to an individual)

- Medication management support services (to achieve planned, therapeutic outcomes)

- Specialized packaging services (customized packs/devices for improving access/adherence)

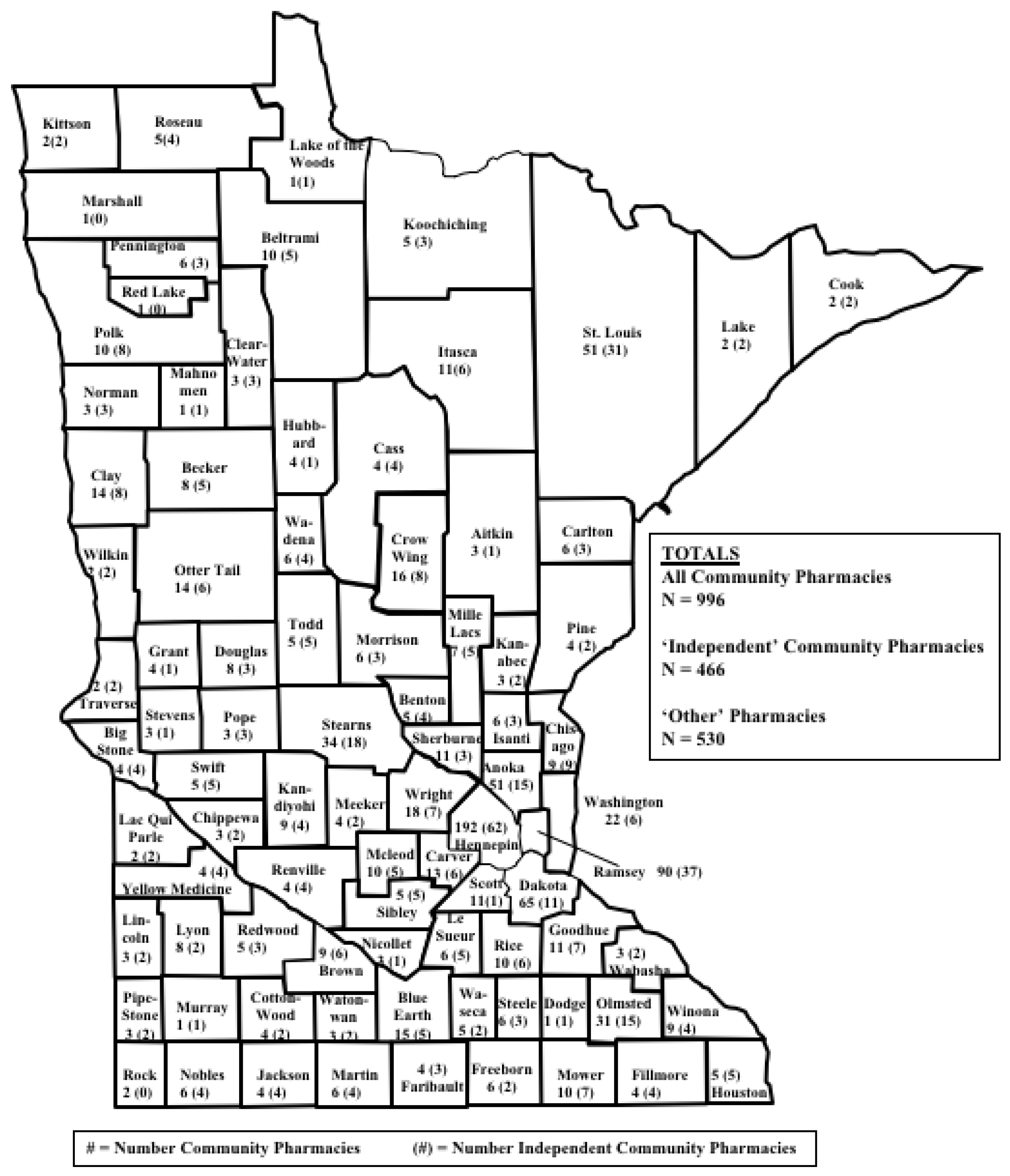

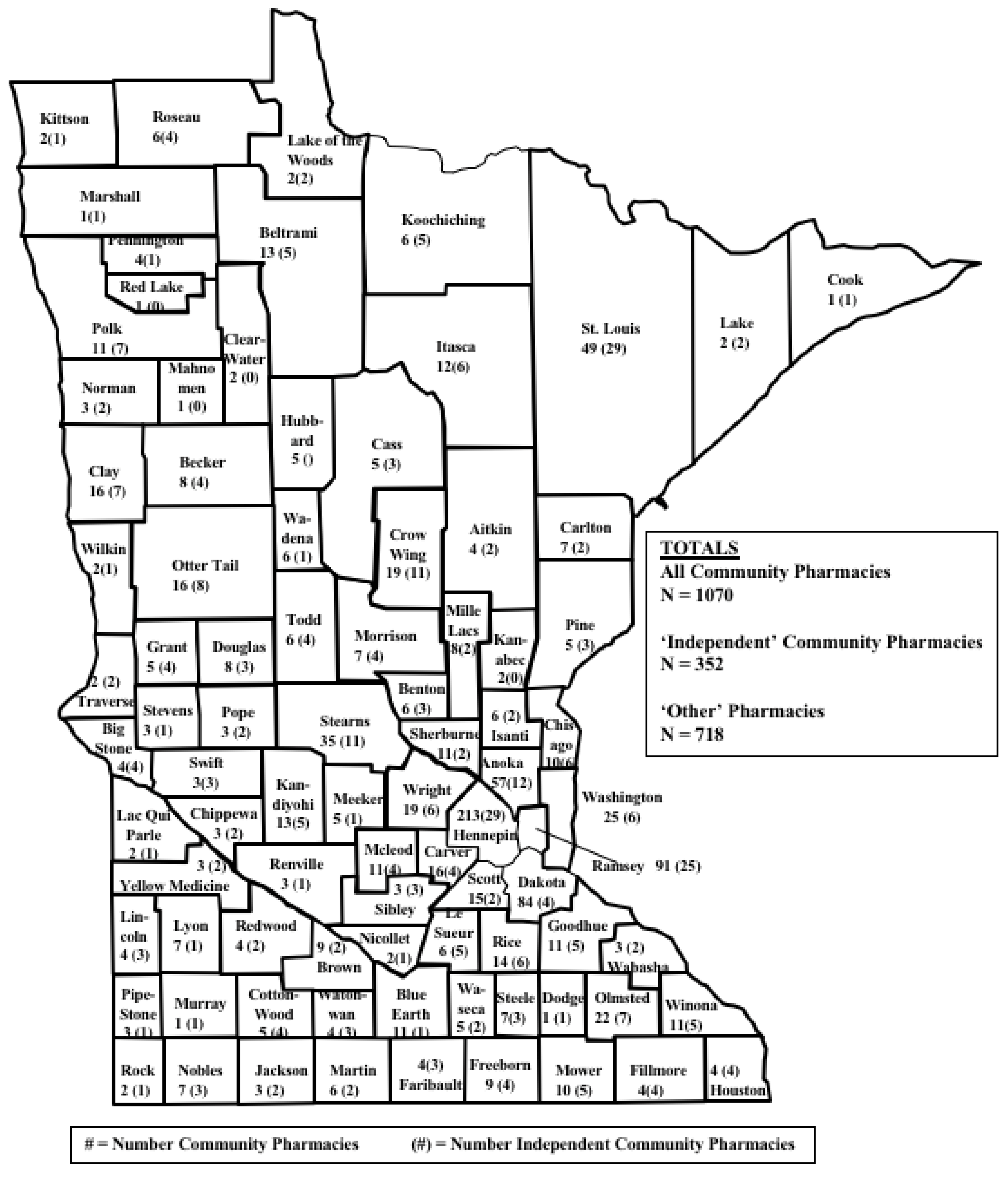

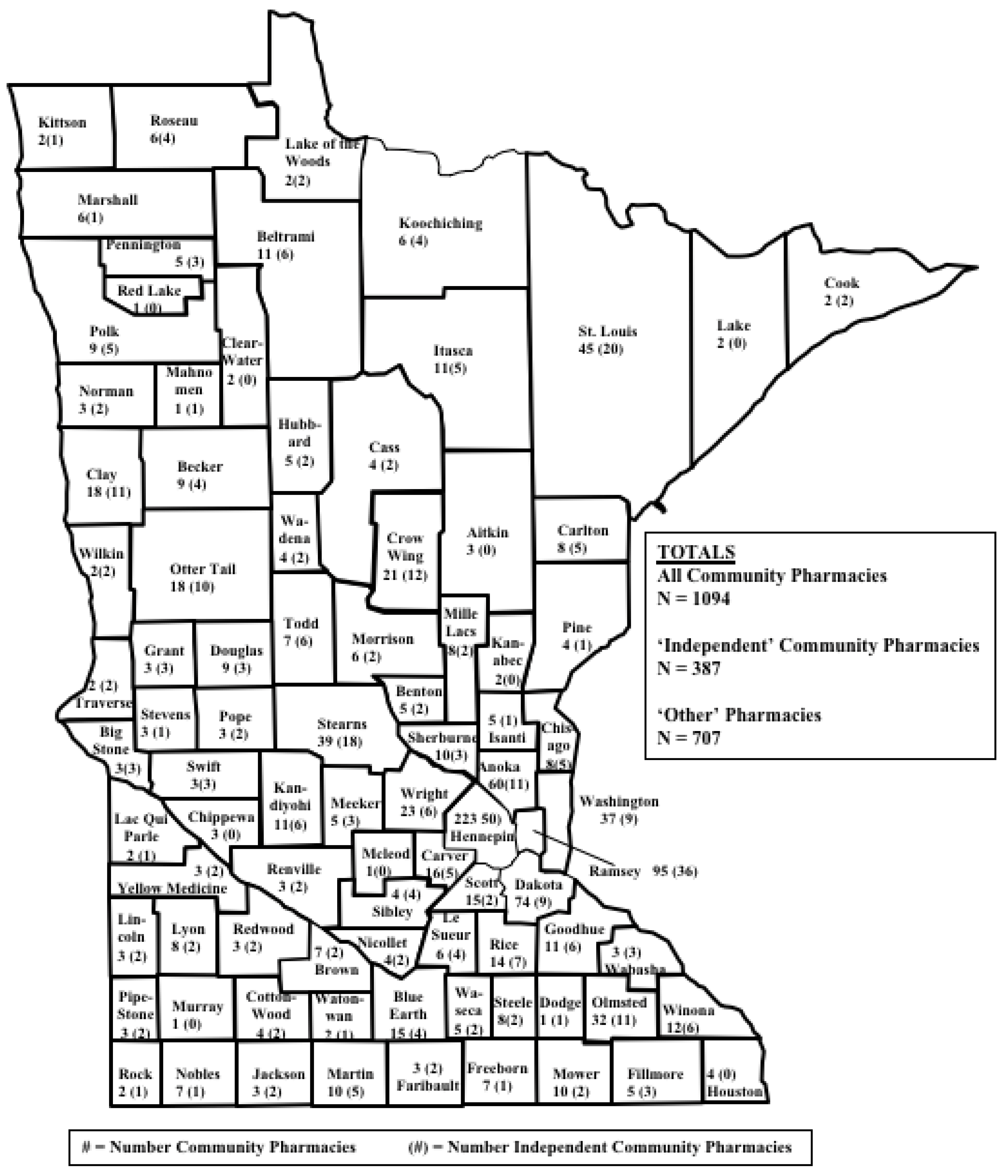

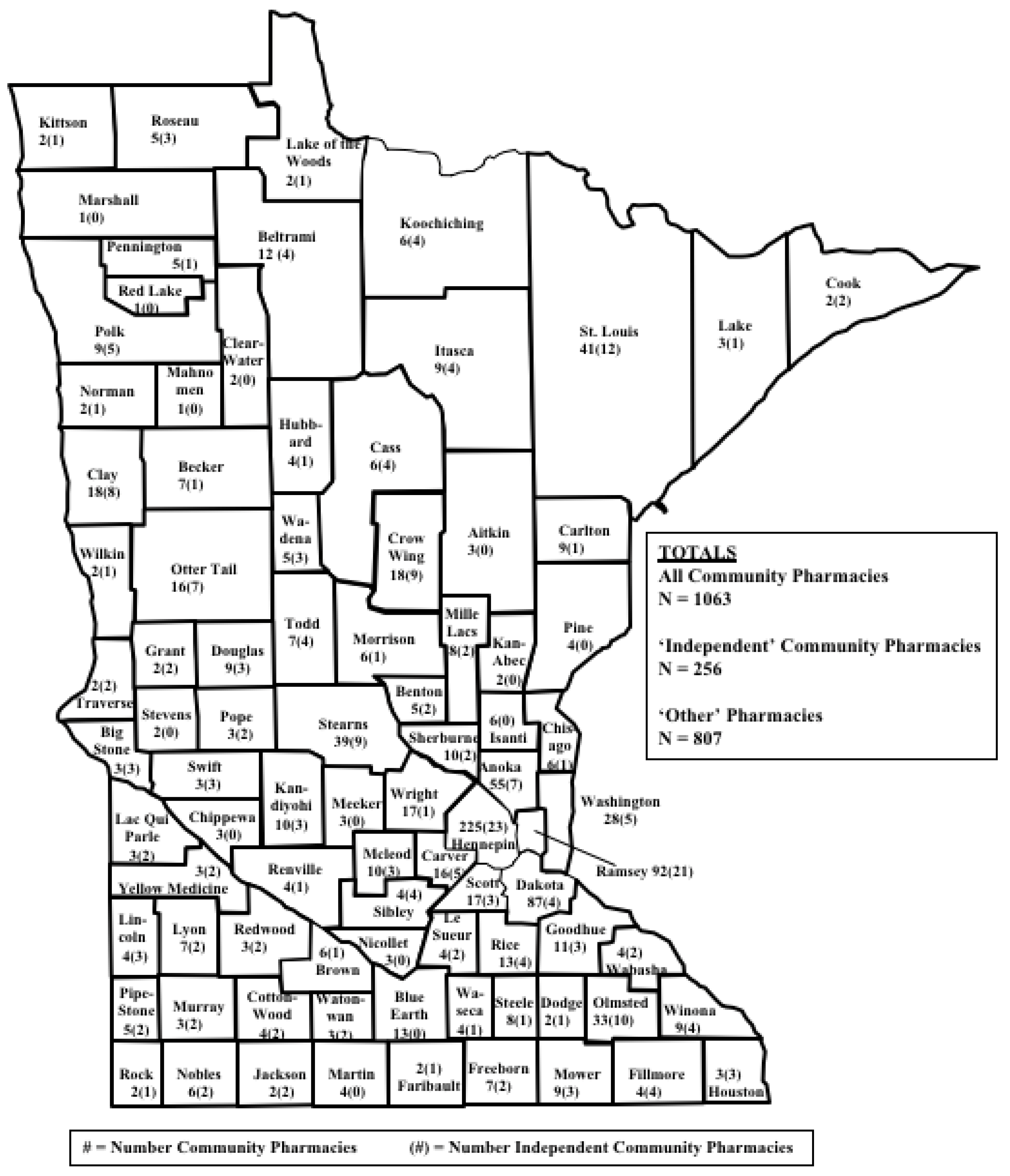

Results

| 2002 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mail-order and medical supply service | 196 (69%) | 413 (43%) |

| Specialty pharmacy distributor | 37 (13%) | 230 (24%) |

| Compounding pharmacy | 33 (12%) | 202 (21%) |

| Medication management support services | 17 (6%) | 96 (10%) |

| Specialized packaging services | 0 (0%) | 19 (2%) |

| Total | 283 (100%) | 960 (100%) |

| In both 2002 and 2022, 20% of the total were considered ‘Walk-In’ Pharmacies.‘Primary Service’ was operationally defined as the primary service function offered to Minnesota residents as described in publicly available records. | ||

Discussion

4.1. Update for the Market Dynamics of Minnesota Community Pharmacies

4.2. The Emergence of Nationally-Scaled Service Models

4.3. Recommendations for Future Research

4.4. Study limitations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS FOR VARIABLES

- USED IN THE 2002-2017 STUDY [1]

- All community pharmacies: Per the state of Minnesota, an “established place(s) in which prescriptions, drugs, medicines, chemicals, and poisons are prepared, compounded, dispensed, vended, distributed, or sold to or for the use of non-hospitalized patients and from which related pharmaceutical care services are provided.”

- Independent community pharmacies: A community pharmacy owned as a single entity or as part of an organization comprising of 10 or fewer community pharmacies.

- Chain community pharmacies: Any community pharmacy owned as part of an organization comprising of more than 10 community pharmacies.

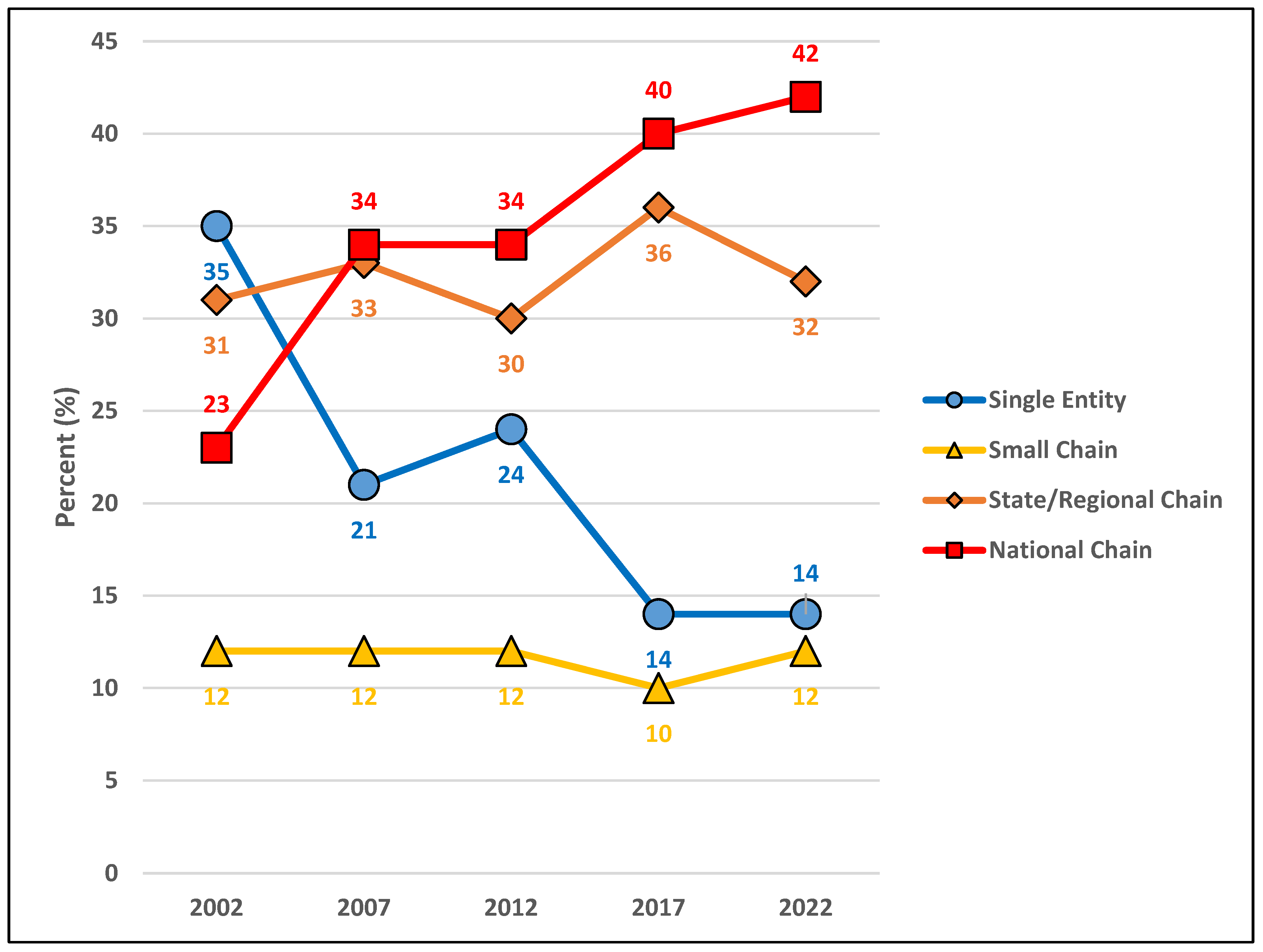

- Single entity: A business organization comprised of one pharmacy in a local market that would be classified under ‘Independent community pharmacies’ for objective 1.

- Small chain: A business organization comprised of 2–10 community pharmacies under common ownership (typically located in a local market) that would be classified under ‘Independent community pharmacies’ for objective 1.

- State/regional chain: A business organization comprised of greater than 10 community pharmacies under common ownership; distributed throughout Minnesota or the Midwest Region (Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin) and that would be classified under ‘Chain community pharmacies’ for objective 1.

- National chain: greater than 10 community pharmacies under common ownership; typically comprised of more than 1000 community pharmacies nationwide, located in most of the 50 states, and that would be classified under ‘Chain community pharmacies’ for objective 1.

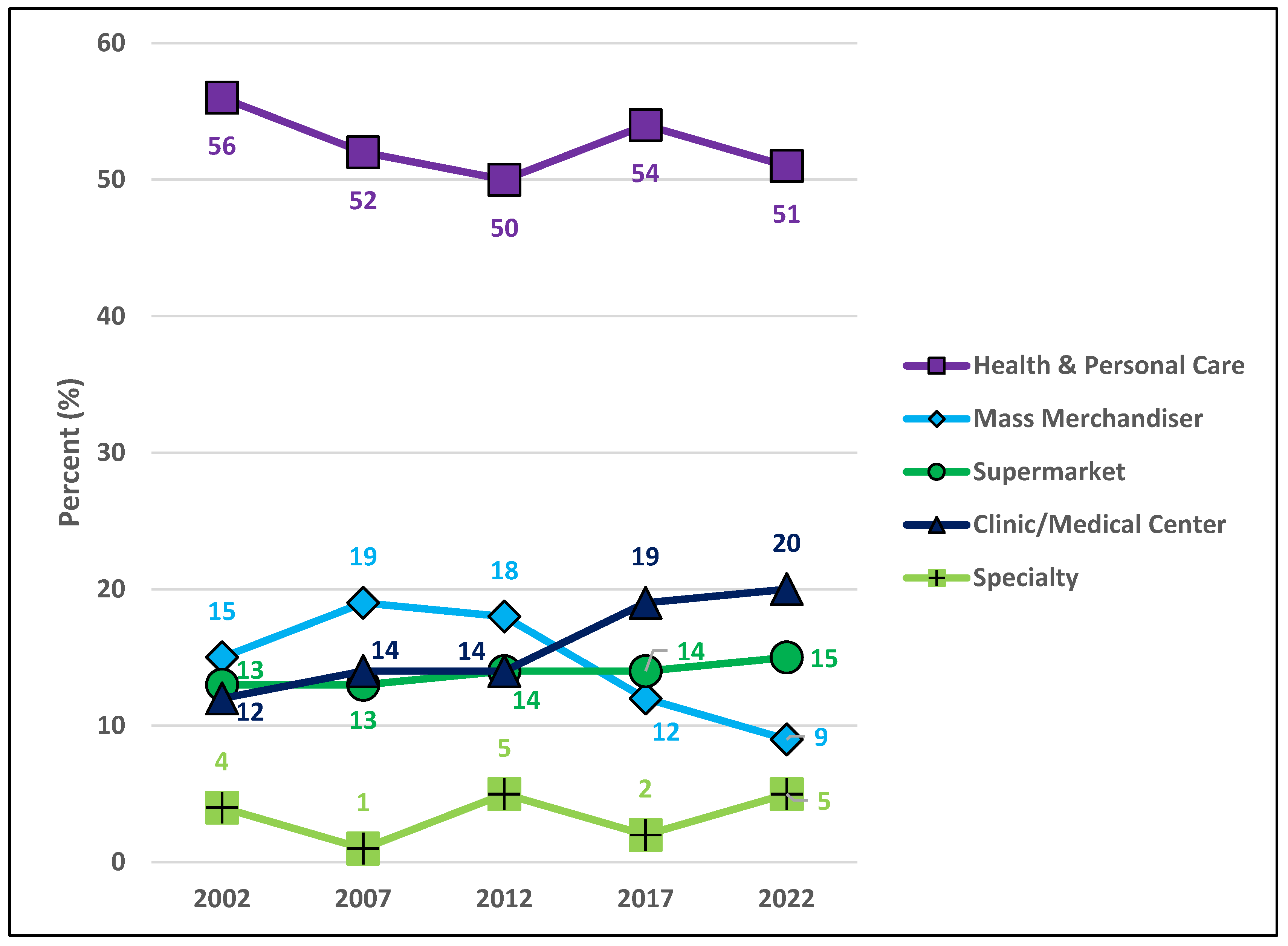

- Health & Personal Care: establishment is considered a pharmacy that also has a “front end”. A relatively large amount of square footage is devoted to the pharmacy and over-the-counter products. Revenue from the pharmacy and over-the-counter product sales is relatively large. The typical reason for patronizing the business is to “go to the pharmacy.” Locational convenience is a primary patronage motive. This type of pharmacy has also been known as a retail pharmacy.

- Mass merchandiser: establishment is considered a big box retail store that also has a “pharmacy.” A relatively small amount of square footage is devoted to the pharmacy and over-the-counter products. Revenue from the pharmacy and over-the-counter product sales is relatively small. The typical reason for patrons to visit the business is to “go to the big box retailer.” Retail shopping convenience is a primary patronage motive.

- Supermarket: establishment is considered a grocery store that also has a “pharmacy.” A relatively small amount of square footage is devoted to the pharmacy and over-the-counter products. Revenue from the pharmacy and over-the-counter product sales is relatively small. The typical reason for patronizing the business is to “go to the grocery store.” Grocery shopping convenience is a primary patronage motive.

- Clinic/medical center: establishment is considered a clinic that also has a “pharmacy.” A relatively small amount of square footage is devoted to the pharmacy and over-the-counter products. Typically, revenue from the pharmacy and over-the-counter product sales is relatively small. The typical reason for patronizing the business is to “go to the clinic.” In some cases, the pharmacy is a stand-alone business but is still considered to be closely associated with the clinic or medical center that is nearby. In many cases, the pharmacy name is the same as the clinic name (XYZ Clinic, XYZ Medical Center, XYZ Pharmacy). Health care visit convenience is a primary patronage motive.

- Specialty: establishment is considered a specialty business. Typically, all of the square footage is devoted to the pharmacy. Revenue for this business typically comes completely from the specialty services offered by the pharmacy. The typical reason for patronizing the business is to “receive unique pharmaceutical services” to meet patient care needs. Examples of specialty pharmacies include those focused upon renal services, compounding, veterinary pharmacy, long-term care, oncology, infusion, nuclear, outpatient treatment centers, HIV medication services, specialty pharmaceuticals. Need for specialty services is a primary patronage motive.

Appendix B

- Findings for Objectives 1 and 2 (2002 through 2022)

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

2002-07 | 2007-12 | 2012-17 | 2017-22 |

| All community pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 18% | 29% | 38% | 36% |

| Stayed the same | 36% | 43% | 40% | 34% |

| Gained pharmacies | 46% | 29% | 22% | 30% |

| Independent pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 55% | 33% | 54% | 14% |

| Stayed the same | 25% | 29% | 30% | 39% |

| Gained pharmacies | 20% | 38% | 16% | 47% |

| Chain pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 8% | 31% | 16% | 49% |

| Stayed the same | 36% | 38% | 45% | 32% |

| Gained pharmacies | 56% | 31% | 39% | 20% |

| Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic | Counties with <0 p/mi2 change | Counties with 0-5 p/mi2 change | Counties with >5 p/mi2 change | Overall |

| N = 43 | N = 29 | N = 15 | N = 87 | |

| All community pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 23% | 17% | 7% | 18% |

| Stayed the same | 51% | 24% | 13% | 36% |

| Gained pharmacies | 26% | 59% | 80% | 46% |

| p = 0.002 | ||||

| Independent pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 56% | 41% | 80% | 55% |

| Stayed the same | 23% | 35% | 13% | 25% |

| Gained pharmacies | 21% | 24% | 7% | 20% |

| p = 0.185 | ||||

| Chain pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 12% | 3% | 7% | 8% |

| Stayed the same | 42% | 45% | 0% | 36% |

| Gained pharmacies | 47% | 52% | 93% | 56% |

| p = 0.014 |

| Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic | Counties with <0 p/mi2 change | Counties with 0-5 p/mi2 change | Counties with >5 p/mi2 change | Overall |

| N = 44 | N = 31 | N = 12 | N = 87 | |

| All community pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 30% | 26% | 33% | 29% |

| Stayed the same | 55% | 36% | 17% | 43% |

| Gained pharmacies | 16% | 39% | 50% | 29% |

| p = 0.052 | ||||

| Independent pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 43% | 23% | 25% | 33% |

| Stayed the same | 39% | 19% | 17% | 29% |

| Gained pharmacies | 18% | 58% | 58% | 38% |

| p = 0.005 | ||||

| Chain pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 18% | 45% | 42% | 31% |

| Stayed the same | 54% | 26% | 8% | 38% |

| Gained pharmacies | 27% | 29% | 50% | 31% |

| p = 0.009 |

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

Counties with <0 p/mi2 change N = 44 |

Counties with 0-5 p/mi2 change N = 33 |

Counties with >5 p/mi2 change N = 10 |

Overall N = 87 |

| All community pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 32% | 46% | 40% | 38% |

| Stayed the same | 48% | 36% | 20% | 40% |

| Gained pharmacies | 21% | 18% | 40% | 22% |

| p = 0.349 | ||||

| Independent pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 43% | 61% | 80% | 54% |

| Stayed the same | 36% | 27% | 10% | 30% |

| Gained pharmacies | 21% | 12% | 10% | 16% |

| p = 0.234 | ||||

| Chain pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 16% | 12% | 30% | 16% |

| Stayed the same | 59% | 36% | 10% | 45% |

| Gained pharmacies | 25% | 52% | 60% | 39% |

| p = 0.022 |

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

Counties with <0 p/mi2 change N = 31 |

Counties with 0-5 p/mi2 change N = 30 |

Counties with >5 p/mi2 change N = 26 |

Overall N = 87 |

| All community pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 16% | 44% | 42% | 36% |

| Stayed the same | 56% | 32% | 0% | 34% |

| Gained pharmacies | 28% | 24% | 25% | 30% |

| p = 0.004 | ||||

| Independent Pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 8% | 20% | 0% | 14% |

| Stayed the same | 52% | 38% | 18% | 39% |

| Gained pharmacies | 40% | 42% | 83% | 47% |

| p = 0.038 | ||||

| Chain Pharmacies | ||||

| Lost pharmacies | 28% | 60% | 50% | 49% |

| Stayed the same | 52% | 26% | 8% | 32% |

| Gained pharmacies | 20% | 14% | 42% | 20% |

| p = 0.010 |

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

Metropolitan counties N = 21 |

Non-metropolitan counties N = 66 |

Overall N = 87 |

| All community pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 14% | 19% | 18% |

| Stayed the same | 19% | 41% | 36% |

| Gained pharmacies | 67% | 39% | 46% |

| p = 0.083 | |||

| Independent pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 81% | 47% | 55% |

| Stayed the same | 14% | 29% | 25% |

| Gained pharmacies | 5% | 24% | 20% |

| p = 0.021 | |||

| Chain pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 5% | 9% | 8% |

| Stayed the same | 19% | 41% | 36% |

| Gained pharmacies | 76% | 50% | 56% |

| p = 0.108 |

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

Metropolitan counties N = 21 |

Non-metropolitan counties N = 66 |

Overall N = 87 |

||

| All community pharmacies | |||||

| Lost pharmacies | 33% | 27% | 29% | ||

| Stayed the same | 24% | 49% | 43% | ||

| Gained pharmacies | 43% | 24% | 29% | ||

| p = 0.111 | |||||

| Independent pharmacies | |||||

| Lost pharmacies | 33% | 33% | 33% | ||

| Stayed the same | 14% | 33% | 29% | ||

| Gained pharmacies | 52% | 33% | 38% | ||

| p = 0.171 | |||||

| Chain pharmacies | |||||

| Lost pharmacies | 48% | 26% | 31% | ||

| Stayed the same | 24% | 42% | 38% | ||

| Gained pharmacies | 29% | 32% | 31% | ||

| p = 0.138 | |||||

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

Metropolitan counties N = 27 |

Non-metropolitan counties N = 60 |

Overall N = 87 |

| All community pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 41% | 37% | 38% |

| Stayed the same | 30% | 45% | 40% |

| Gained pharmacies | 30% | 18% | 22% |

| p = 0.323 | |||

| Independent pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 67% | 48% | 54% |

| Stayed the same | 22% | 33% | 30% |

| Gained pharmacies | 11% | 18% | 16% |

| p = 0.282 | |||

| Chain pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 19% | 15% | 16% |

| Stayed the same | 22% | 55% | 45% |

| Gained pharmacies | 59% | 30% | 39% |

| p = 0.013 |

|

Pharmacy Category County Market Dynamic |

Metropolitan counties N = 27 |

Non-metropolitan counties N = 60 |

Overall N = 87 |

| All community pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 37% | 35% | 36% |

| Stayed the same | 22% | 40% | 35% |

| Gained pharmacies | 41% | 25% | 30% |

| p = 0.195 | |||

| Independent pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 15% | 13% | 14% |

| Stayed the same | 19% | 48% | 39% |

| Gained pharmacies | 67% | 38% | 47% |

| p = 0.024 | |||

| Chain pharmacies | |||

| Lost pharmacies | 48% | 50% | 49% |

| Stayed the same | 15% | 38% | 32% |

| Gained pharmacies | 37% | 12% | 20% |

| p = 0.009 |

| Business organization structure | Pharmacy type | 2002 | 2007 | 2012 | 2017 | 2022 |

| N = 996 | N = 1070 | N = 1094 | N = 1063 | N = 1039 | ||

| Single entity | Health & Personal Care | 281 (28%) | 185 (17%) | 199 (18%) | 127 (12%) | 100 (10%) |

| Mass merchandiser | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Supermarket | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Clinic/medical center | 36 (4%) | 32 (3%) | 28 (3%) | 19 (2%) | 18 (2%) | |

| Specialty | 29 (3%) | 10 (1%) | 33 (3%) | 5 (1%) | 24 (2%) | |

| Total | 346 (35%) | 227 (21%) | 260 (24%) | 151 (14%) | 143 (14%) | |

| Small chain | Health & Personal Care | 98 (10%) | 97 (9%) | 91 (8%) | 83 (8%) | 79 (8%) |

| Mass merchandiser | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Supermarket | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Clinic/medical center | 20 (2%) | 26 (2%) | 30 (3%) | 17 (2%) | 43 (4%) | |

| Specialty | 2 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) | 6 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 6 (1%) | |

| Total | 120 (12%) | 125 (12%) | 127 (12%) | 105 (10%) | 129 (12%) | |

| ALL INDEP | Single Entity + Small Chain | 466 (47%) | 352 (33%) | 387 (35%) | 256 (24%) | 272 (26%) |

| State/regional chain | Health & Personal Care | 99 (10%) | 120 (11%) | 63 (6%) | 66 (6%) | 63 (6%) |

| Mass merchandiser | 13 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Supermarket | 127 (13%) | 139 (13%) | 155 (14%) | 150 (14%) | 151 (15%) | |

| Clinic/medical center | 61 (6%) | 96 (9%) | 83 (8%) | 162 (15%) | 108 (10%) | |

| Specialty | 5 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 14 (1%) | |

| Total | 305 (31%) | 355 (33%) | 330 (30%) | 383 (36%) | 336 (32%) | |

| National chain | Health & Personal Care | 81 (8%) | 152 (14%) | 201 (18%) | 294 (28%) | 287 (28%) |

| Mass merchandiser | 144 (14%) | 209 (20%) | 173 (16%) | 127 (12%) | 92 (9%) | |

| Supermarket | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Clinic/medical center | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (4%) | |

| Specialty | 0 (0%) | 2 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) | 11 (1%) | |

| Total | 225 (23%) | 363 (34%) | 377 (34%) | 423 (40%) | 431 (42%) | |

| ALL CHAIN | State/regional National | 530 (53%) | 718 (67%) | 707 (65%) | 807 (76%) | 767 (74%) |

References

- Olson, A.W.; Schommer, J.C.; Hadsall, R.S. A 15 year ecological comparison for the market dynamics of Minnesota community pharmacies from 2002 to 2017. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, J.C.; Singh, R.L.; Cline, R.R.; Hadsall, R.S. Market dynamics of community pharmacies in Minnesota. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2006, 2, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schommer, J.C.; Yusuf, A.A.; Hadsall, R.S. Market dynamics of community pharmacies in Minnesota, U.S. from 1992 through 2012. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2014, 10, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shcherbakova, N.; Desselle, S. Looking back at US pharmacy’s past to help discern its future. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2020, 54, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabenstein, J.D. Essential services: Quantifying the contributions of America’s pharmacists in COVID-19 clinical interventions. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1929–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, M.; Nielsen, C. The concept of business model scalability. Journal of Business Models 2018, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Angeli, F.; Jaiswal, A.K. Business model innovation for inclusive health care delivery at the bottom of the pyramid. Organization & Environment 2016, 29, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Services MD of H. Minnesota Board of Pharmacy. 2022. Available online: https://mn.gov/boards/pharmacy/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States. US Dep Commer. 1AD. Available online: https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/publications/statistical_abstracts.html (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Minnesota State Demographic Center (SDC). Available online: https://mn.gov/admin/demography/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Perrault, W.D.; Leigh, L.E. Reliability of nominal data based on qualitative judgments. J. Marketing Res. 1989, 26, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolle, R.J.; Strand, L.M.; Morley, P.C. Pharmaceutical Care Practice; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 237–265. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, R. Smart services: Competitive advantage through information-intensive strategies. In Handbook of Services Marketing & Management; Swartz and Iaobucci, Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Schommer, J.C.; Doucette, W.R.; Johnson, K.A.; Planas, L.G. Positioning and integrating medication therapy management. J. Amer. Pharm. Assoc. 2012, 53, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelo, A. US survey signals big shifts in primary care to pharmacy and clinic settings as consumers seek lower medication and healthcare costs. Wolters Kluwer, Health, 7 December 2022. Available online: https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/news/us-survey-signals-big-shifts-in-primary-care-to-pharmacy-and-clinic-settings (accessed on 10 January 2023).

| 2002 | 2007 | 2012 | 2017 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-State | 1171 (81%) | 1263 (76%) | 1253 (69%) | 1262 (62%) | 1129 (54%) |

| Out-of-State | 283 (19%) | 395 (24%) | 557 (31%) | 881 (41%) | 960 (46%) |

| Total | 1454 (100%) | 1658 (100%) | 1810 (100%) | 2143 (100%) | 2089 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).