Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

15 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

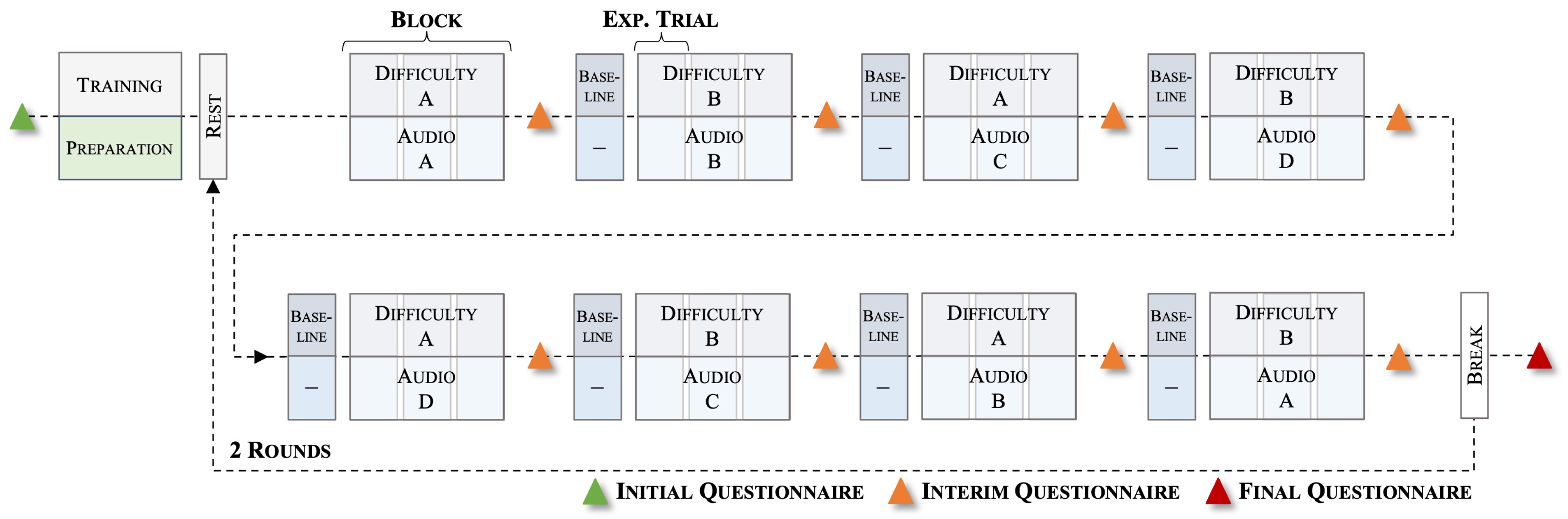

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

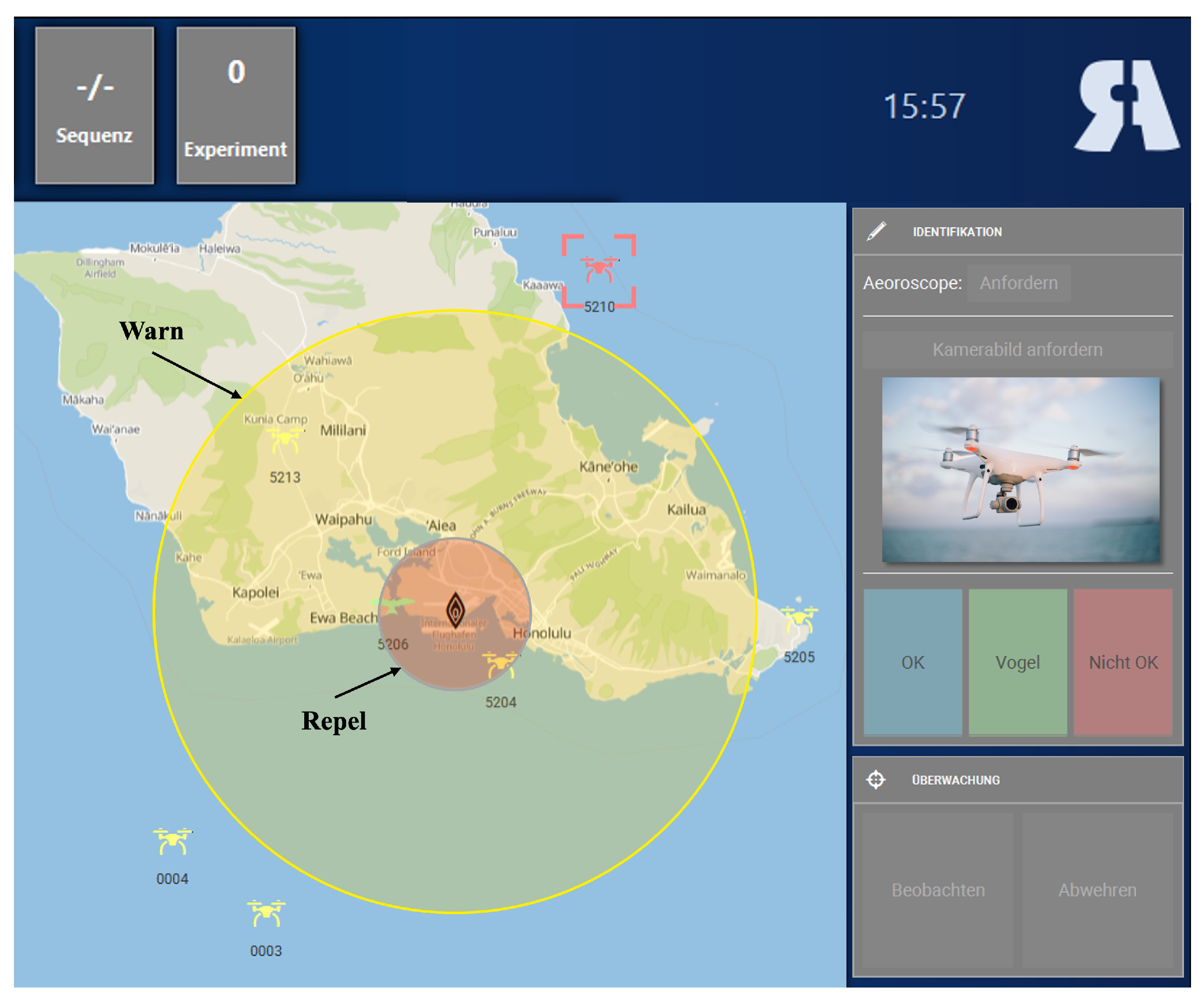

2.2. Experimental Task

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Questionnaires

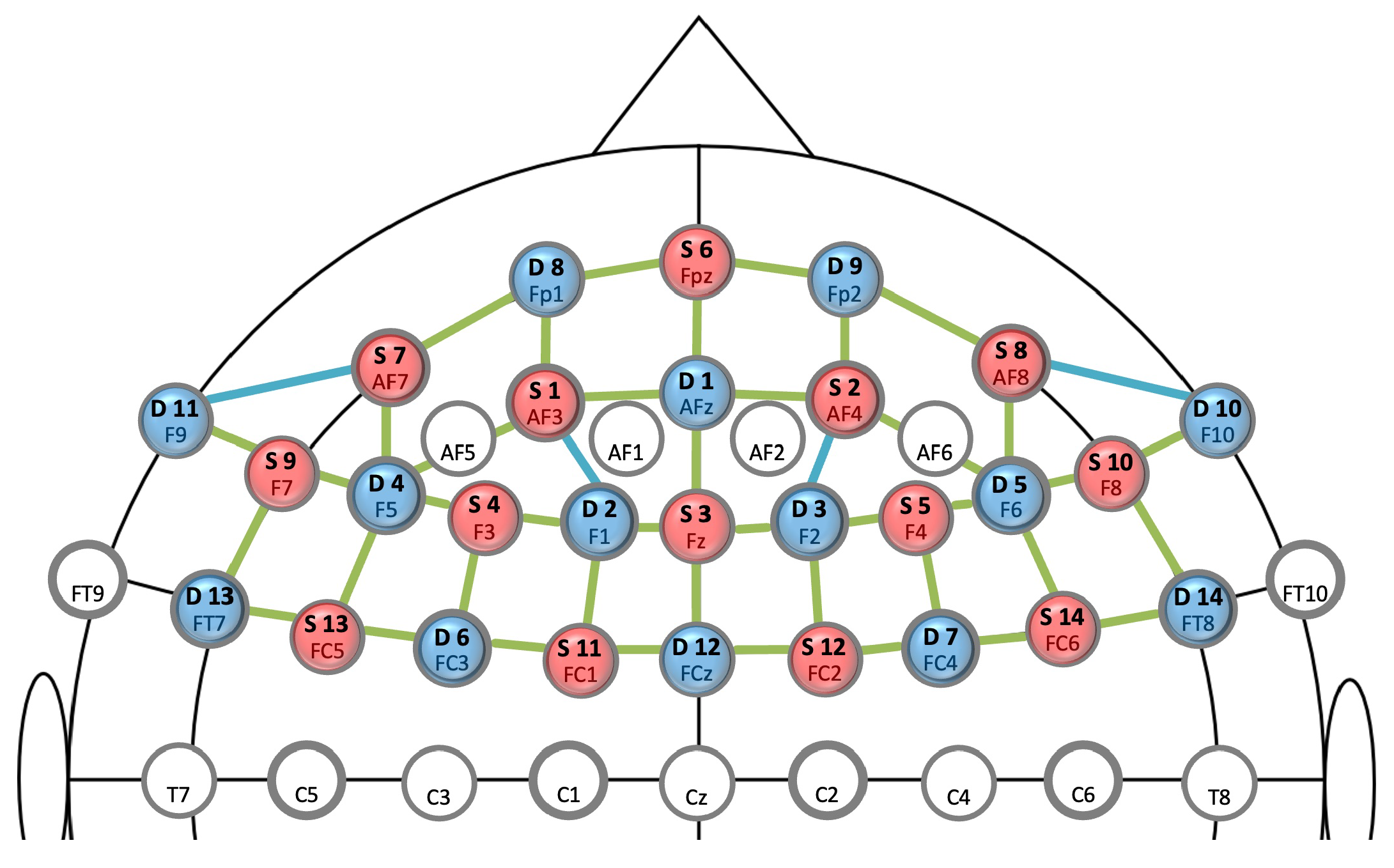

2.3.2. Eye-Tacking, Physiology, and Brain Activity

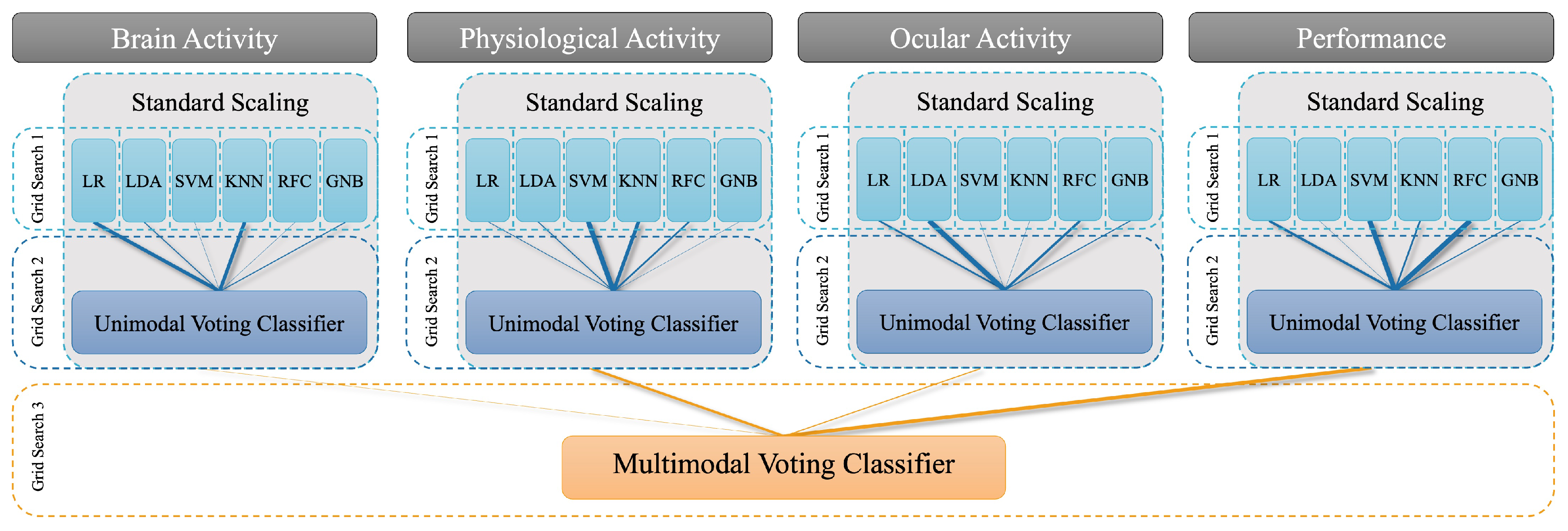

2.4. Data Preprocessing and Machine Learning

2.4.1. Preprocessing of Eye-Tracking Data

2.4.2. Preprocessing of Physiological Data

2.4.3. Preprocessing of fNIRS Data

2.4.4. Feature Extraction

2.4.5. Ground Truth for Machine Learning

2.4.6. Model Evaluation

3. Results

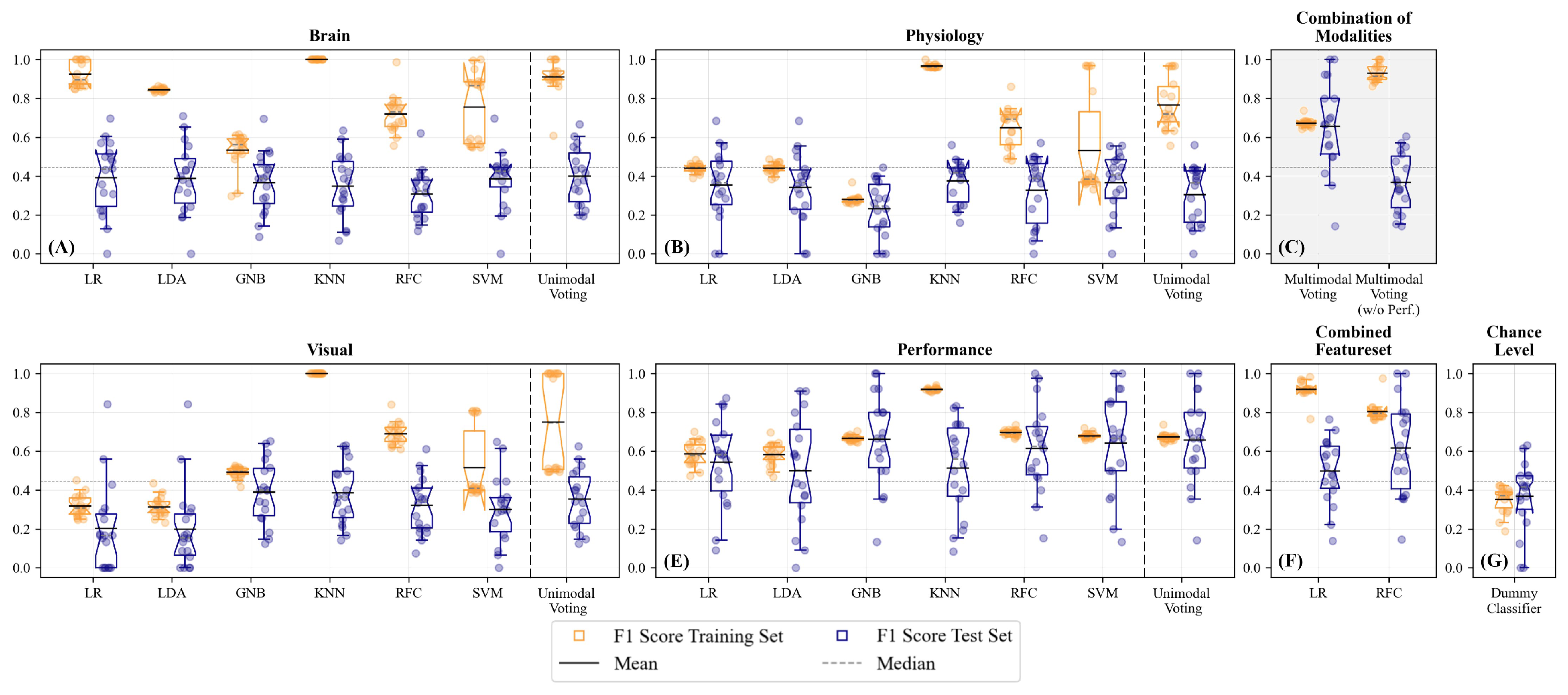

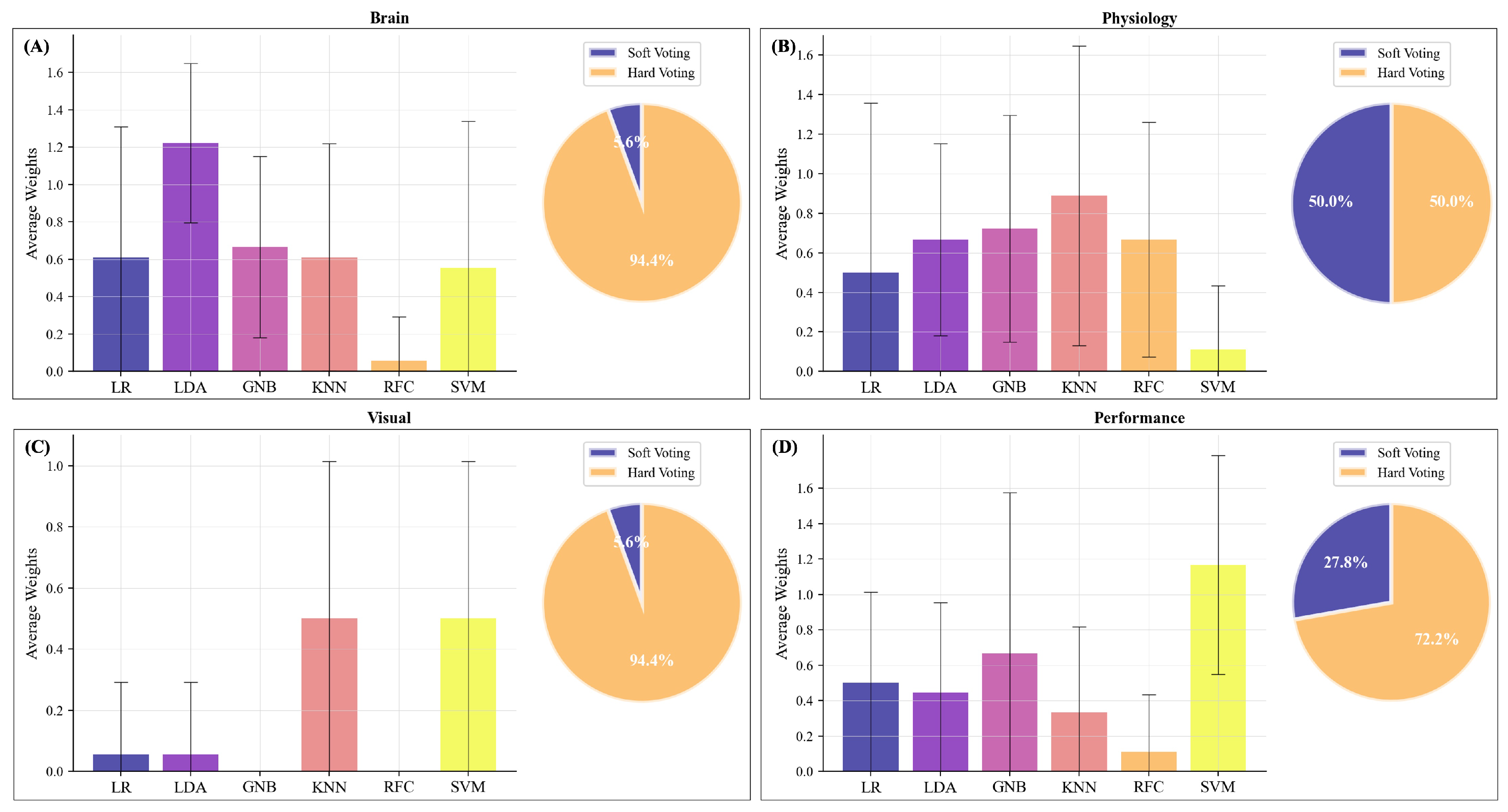

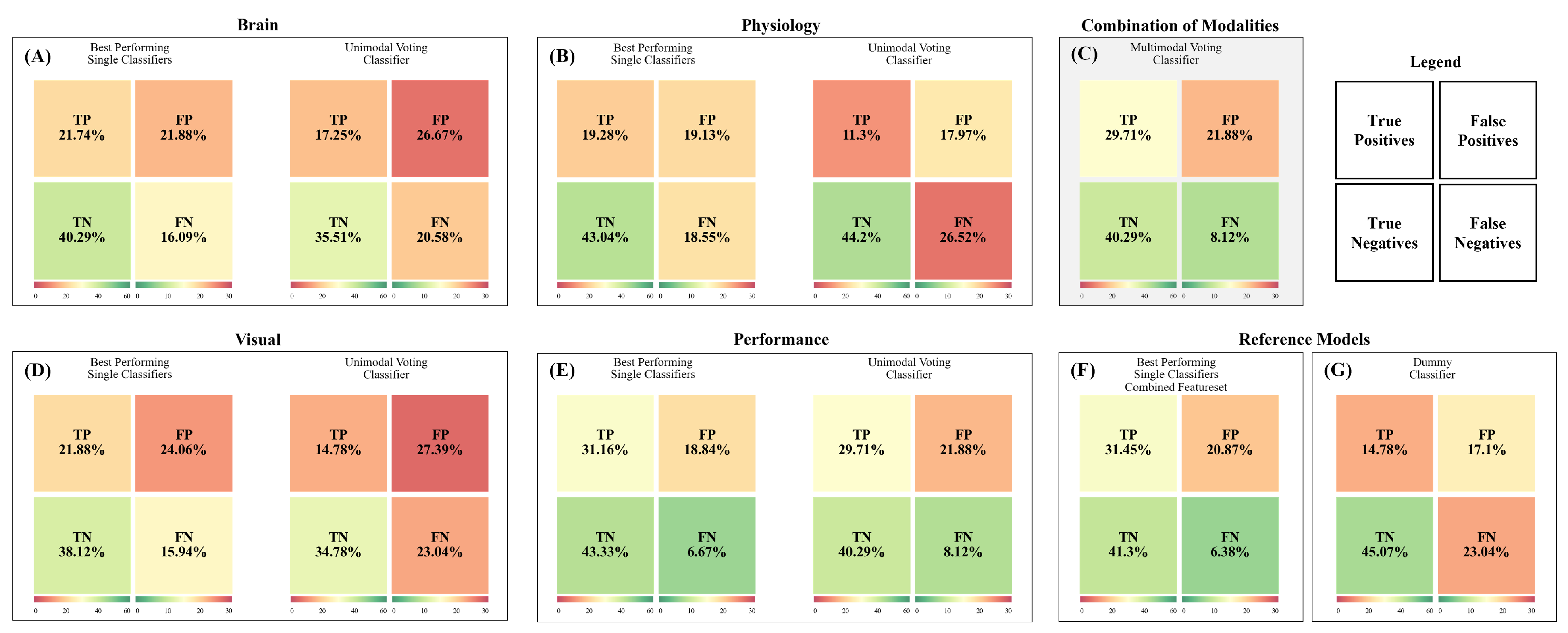

3.1. Unimodal Predictions

3.2. Unimodal Predictions – Brain Activity

3.3. Unimodal Predictions – Physiological Measures

3.4. Unimodal Predictions – Ocular Measures

3.5. Unimodal Predictions – Performance

3.6. Unimodal Predictions based on the Upper Quartile Split

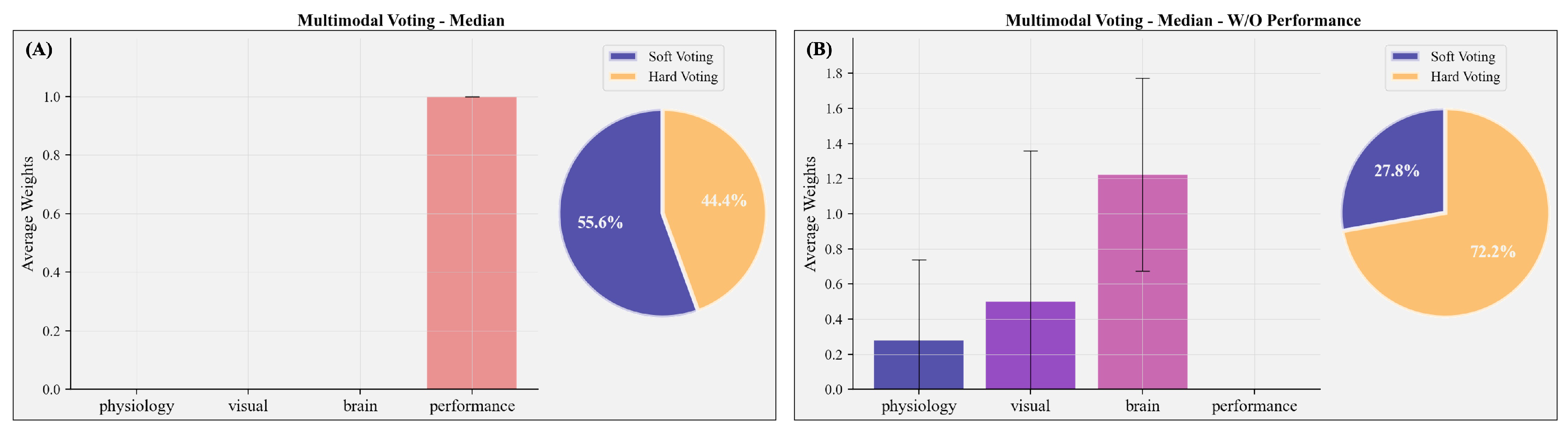

3.7. Unimodal Predictions based on the Experimental Condition

3.8. Multimodal Predictions based on the Median Split

3.9. Multimodal Predictions based on the Upper Quartile Split

3.10. Multimodal Predictions based on the Experimental Condition

4. Discussion

4.1. Using Subjectively Perceived Mental Effort as Ground Truth

4.2. Using Experimentally Induced Mental Effort as Ground Truth

4.3. Generalisation across Subjects

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

4.5. Feature Selection and Data Fusion in Machine Learning

5. Practical Implications and Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| fNIRS | functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| HbO | Oxy-Haemoglobin |

| HbR | Deoxy-Haemoglobin |

| PFC | Prefrontal Cortex |

| WCT | Warship Commander Task |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| GNB | Gaussian Naïve Bayes Classifier |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbor Classifier |

| RFC | Random Forest Classifier |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine Classifier |

References

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In Advances in Psychology; Hancock, P.A.; Meshkati, N., Eds.; North-Holland, 1988; Vol. 52, pp. 139–183. [CrossRef]

- Young, M.S.; Brookhuis, K.A.; Wickens, C.D.; Hancock, P.A. State of science: Mental workload in ergonomics. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Tuovinen, J.E.; Tabbers, H.; Van Gerven, P.W.M. Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist 2003, 38, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, K.; Arshad, S.Z.; Khawaji, A.; Conway, D. Robust multimodal cognitive load measurement; Human–Computer Interaction Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.Z. Cognitive load measurement and application: A theoretical framework for meaningful research and practice; Routledge: New York, NY, US, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- von Lühmann, A. Multimodal instrumentation and methods for neurotechnology out of the lab. Doctoral Dissertation, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, 2018. Publication Title: Fakultät IV - Elektrotechnik und Informatik. [CrossRef]

- Charles, R.L.; Nixon, J. Measuring mental workload using physiological measures: A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics 2019, 74, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, A.; Ayaz, H. The age of neuroergonomics: Towards ubiquitous and continuous measurement of brain function with fNIRS. Japanese Psychological Research 2018, 60, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benerradi, J.; Maior, H.A.; Marinescu, A.; Clos, J.; Wilson, M.L. Mental workload using fNIRS data from HCI tasks ground truth: Performance, evaluation, or condition. Proceedings of the Halfway to the Future Symposium; Association for Computing Machinery: Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midha, S.; Maior, H.A.; Wilson, M.L.; Sharples, S. Measuring mental workload variations in office work tasks using fNIRS. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2021, 147, 102580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzetoglu, K.; Bunce, S.; Izzetoglu, M.; Onaral, B.; Pourrezaei, K. fNIR spectroscopy as a measure of cognitive task load. Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2003, Vol. 4, pp. 3431–3434 Vol.4. Journal Abbreviation: Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37439). [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, H.; Shewokis, P.A.; Bunce, S.; Izzetoglu, K.; Willems, B.; Onaral, B. Optical brain monitoring for operator training and mental workload assessment. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herff, C.; Heger, D.; Fortmann, O.; Hennrich, J.; Putze, F.; Schultz, T. Mental workload during n-back task - Quantified in the prefrontal cortex using fNIRS. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 935. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.K.; Freedman, D.J.; Wallis, J.D. The prefrontal cortex: Categories, concepts and cognition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 2002, 357, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehais, F.; Lafont, A.; Roy, R.; Fairclough, S. A neuroergonomics approach to mental workload, engagement and human performance. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2020, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiloni, F. Mental workload monitoring: New perspectives from neuroscience. Human Mental Workload: Models and Applications; Longo, L., Leva, M.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Volume 1107, Communications in Computer and Information Science; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.; McDonald, N.J.; Trejo, L.J. Psycho-physiological sensor techniques: An overview. In Foundations of Augmented Cognition; Schmorrow, D.D., Ed.; CRC Press, 2005; Vol. 11, pp. 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Wierwille, W.W. Physiological measures of aircrew mental workload. Human Factors 1979, 21, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.F. Physiological metrics of mental workload: A review of recent progress. In Multiple-task performance; Damos, D.L., Ed.; CRC Press: London, 1991; pp. 279–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backs, R.W. Application of psychophysiological models to mental workload. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2000, 44, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirican, A.C.; Göktürk, M. Psychophysiological measures of human cognitive states applied in human computer interaction. Procedia Computer Science 2011, 3, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, A.; Reiner, M. Real time EEG based measurements of cognitive load indicates mental states during learning. Journal of Educational Data Mining 2017, 9, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Tan, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Qu, X.; Zhang, T. A systematic review of physiological measures of mental workload. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romine, W.L.; Schroeder, N.L.; Graft, J.; Yang, F.; Sadeghi, R.; Zabihimayvan, M.; Kadariya, D.; Banerjee, T. Using machine learning to train a wearable device for measuring students’ cognitive load during problem-solving activities based on electrodermal activity, body temperature, and heart rate: Development of a cognitive load tracker for both personal and classroom use. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uludağ, K.; Roebroeck, A. General overview on the merits of multimodal neuroimaging data fusion. NeuroImage 2014, 102, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.D.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.H.; Yu, X.; Yao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, H.; Li, M.; Jiménez-Mesa, C.; Ramirez, J.; Martinez, F.J.; Gorriz, J.M. Advances in multimodal data fusion in neuroimaging: Overview, challenges, and novel orientation. Information Fusion 2020, 64, 149–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debie, E.; Rojas, R.F.; Fidock, J.; Barlow, M.; Kasmarik, K.; Anavatti, S.; Garratt, M.; Abbass, H.A. Multimodal fusion for objective assessment of cognitive workload: A review. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2021, 51, 1542–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimesch, W. Evoked alpha and early access to the knowledge system: The P1 inhibition timing hypothesis. Brain Research 2011, 1408, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirzberger, M.; Herms, R.; Esmaeili Bijarsari, S.; Eibl, M.; Rey, G.D. Schema-related cognitive load influences performance, speech, and physiology in a dual-task setting: A continuous multi-measure approach. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 2018, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemm, S.; Blankertz, B.; Dickhaus, T.; Müller, K.R. Introduction to machine learning for brain imaging. Multivariate Decoding and Brain Reading 2011, 56, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.A.T.; Adalı, T.; Ba, D.; Buzsáki, G.; Carlson, D.; Heller, K.; Liston, C.; Rudin, C.; Sohal, V.S.; Widge, A.S.; Mayberg, H.S.; Sapiro, G.; Dzirasa, K. A shared vision for machine learning in neuroscience. The Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 38, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herms, R.; Wirzberger, M.; Eibl, M.; Rey, G.D. CoLoSS: Cognitive load corpus with speech and performance data from a symbol-digit dual-task. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation; European Language Resources Association: Miyazaki, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ladouce, S.; Donaldson, D.I.; Dudchenko, P.A.; Ietswaart, M. Understanding minds in real-world environments: Toward a mobile cognition approach. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2017, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, N. Attention, distraction, and cognitive control under load. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2010, 19, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.D.; Hitch, G. Working Memory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Bower, G.H., Ed.; Academic Press, 1974; Vol. 8, pp. 47–89. [CrossRef]

- Soerqvist, P.; Dahlstroem, O.; Karlsson, T.; Rönnberg, J. Concentration: The neural underpinnings of how cognitive load shields against distraction. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2016, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikin, A. The link between auditory salience and emotion intensity. Cognition and Emotion 2020, 34, 1246–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcos, F.; Iordan, A.D.; Dolcos, S. Neural correlates of emotion–cognition interactions: A review of evidence from brain imaging investigations. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 2011, 23, 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea-Penna, G.M.; Frank, S.M.; Heatherton, T.F.; Tse, P.U. Distracting tracking: Interactions between negative emotion and attentional load in multiple-object tracking. Emotion 2017, 17, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, S.; Satpute, A.B.; Atzil, S.; Field, A.P.; Hitchcock, C.; Black, M.; Barrett, L.F.; Dalgleish, T. The impact of affective information on working memory: A pair of meta-analytic reviews of behavioral and neuroimaging evidence. Psychological Bulletin 2019, 145, 566–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banbury, S.; Berry, D.C. Disruption of office-related tasks by speech and office noise. British Journal of Psychology 1998, 89, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebl, A.; Haller, J.; Jödicke, B.; Baumgartner, H.; Schlittmeier, S.; Hellbrück, J. Combined effects of acoustic and visual distraction on cognitive performance and well-being. Applied Ergonomics 2012, 43, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuilleumier, P.; Schwartz, S. Emotional facial expressions capture attention. Neurology 2001, 56, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waytowich, N.R.; Lawhern, V.J.; Bohannon, A.W.; Ball, K.R.; Lance, B.J. Spectral transfer learning using information geometry for a user-independent brain-computer interface. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2016, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: A compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, B.; Pham, T.; Blaney, G.; Haga, Z.; Sassaroli, A.; Fantini, S.; Aeron, S. Domain adaptation for robust workload level alignment between sessions and subjects using fNIRS. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2021, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotte, F.; Bougrain, L.; Cichocki, A.; Clerc, M.; Congedo, M.; Rakotomamonjy, A.; Yger, F. A review of classification algorithms for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces: A 10 year update. Journal of Neural Engineering 2018, 15, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, Z.; Cui, J.; Sourina, O.; Müller-Wittig, W. EEG-based cross-subject mental fatigue recognition. Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyberworlds 2019, 2019, pp. 247–252 Journal Abbreviation: 2019 International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.; Stasch, S.M.; Schmitz-Hübsch, A.; Fuchs, S. Quantitative scoring system to assess performance in experimental environments. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions; ThinkMind: Nice, France, 2021; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, F.; Paeschke, A.; Rolfes, M.; Sendlmeier, W.; Weiss, B. A database of German emotional speech. Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology; , 2005; Vol. 5, p. 1520. Journal Abbreviation: 9th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology Publication Title: 9th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Group, P.S. .E. Warship Commander 4.4, 2003.

- St John, M.; Kobus, D.A.; Morrison, J.G. DARPA augmented cognition technical integration experiment (TIE). Technical Report ADA42 0147, Pacific Science and Engineering Group, San Diego, CA, USA, 2003.

- Toet, A.; Kaneko, D.; Ushiama, S.; Hoving, S.; de Kruijf, I.; Brouwer, A.M.; Kallen, V.; van Erp, J.B.F. EmojiGrid: A 2D pictorial scale for the assessment of food elicited emotions. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.; Romão, T.; Correia, N. CAAT: A discrete approach to emotion assessment. Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory (BFI-K):. Diagnostica 2005, 51, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, L.; Glanzmann, P.; Schaffner, P.; Spielberger, C.D. Das State-Trait-Angstinventar; Beltz: Weinheim, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bankstahl, U.; Görtelmeyer, R. APSA: Attention and Performance Self-Assessment - deutsche Fassung; Elektronisches Testarchiv, ZPID (Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information)–Testarchiv: Trier, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, A.S.; Rief, W.; Hilbert, A. Psychometric properties of the German version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, Version 11 (BIS–11) for adolescents. Perceptual and Motor Skills 2011, 112, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunemann, J.; Unni, A.; Ihme, K.; Jipp, M.; Rieger, J.W. Demonstrating brain-level interactions between visuospatial attentional demands and working memory load while driving using functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2019, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimeo Morais, G.A.; Balardin, J.B.; Sato, J.R. fNIRS Optodes’ Location Decider (fOLD): A toolbox for probe arrangement guided by brain regions-of-interest. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dink, J.W.; Ferguson, B. eyetrackingR: An R library for eye-tracking data analysis, 2015.

- Forbes, S. PupillometryR: An R package for preparing and analysing pupillometry data. Journal of Open Source Software 2020, 5, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I.; Sirois, S. Infant cognition: Going full factorial with pupil dilation. Developmental Ccience 2009, 12, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Malsburg, T. saccades: Detection of fixations in eye-tracking data, 2015.

- Gramfort, A.; Luessi, M.; Larson, E.; Engemann, D.A.; Strohmeier, D.; Brodbeck, C.; Parkkonen, L.; Hämäläinen, M.S. MNE Software for Processing MEG and EEG Data. NeuroImage 2014, 86, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, R.; Larson, E.D.; Shader, M.J.; Innes-Brown, H.; Van Yper, L.; Lee, A.K.C.; Sowman, P.F.; McAlpine, D. Analysis methods for measuring passive auditory fNIRS responses generated by a block-design paradigm. Neurophotonics 2021, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, M.A.; Lühmann, A.v.; Scholkmann, F.; Gervain, J.; Dan, I.; Ayaz, H.; Boas, D.; Cooper, R.J.; Culver, J.; Elwell, C.E.; Eggebrecht, A.; Franceschini, M.A.; Grova, C.; Homae, F.; Lesage, F.; Obrig, H.; Tachtsidis, I.; Tak, S.; Tong, Y.; Torricelli, A.; Wabnitz, H.; Wolf, M. Best practices for fNIRS publications. Neurophotonics 2021, 8, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollonini, L.; Olds, C.; Abaya, H.; Bortfeld, H.; Beauchamp, M.S.; Oghalai, J.S. Auditory cortex activation to natural speech and simulated cochlear implant speech measured with functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Hearing Research 2014, 309, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishburn, F.A.; Ludlum, R.S.; Vaidya, C.J.; Medvedev, A.V. Temporal Derivative Distribution Repair (TDDR): A motion correction method for fNIRS. NeuroImage 2019, 184, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saager, R.B.; Berger, A.J. Direct characterization and removal of interfering absorption trends in two-layer turbid media. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2005, 22, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, A. Bestimmung der Absorption des rothen Lichts in farbigen Flüssigkeiten. Annalen der Physik und Chemie 1852, 86, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiratti, J.B.; Le Douget, J.E.; Le Van Quyen, M.; Essid, S.; Gramfort, A. An ensemble learning approach to detect epileptic seizures from long intracranial EEG recordings. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing 2018, 2018, pp. 856–860 Journal Abbreviation: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, H.O.; Cengiz, C.; Demiral, I.; Ozmen, M.M.; Omurtag, A. High density optical neuroimaging predicts surgeons’s subjective experience and skill levels. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkley, N.; Xu, K.M.; Krell, M. Analyzing relationships between causal and assessment factors of cognitive load: Associations between objective and subjective measures of cognitive load, stress, interest, and self-concept. Frontiers in Education 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Raschka, S. MLxtend: Providing machine learning and data science utilities and extensions to Python’s scientific computing stack. Journal of Open Source Software 2018, 3, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.; Finch, S. Inference by eye: Confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist 2005, 60, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranchet, M.; Morgan, J.C.; Akinwuntan, A.E.; Devos, H. Cognitive workload across the spectrum of cognitive impairments: A systematic review of physiological measures. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2017, 80, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; De Winter, J.; Hancock, P.A. What do subjective workload scales really measure? Operational and representational solutions to divergence of workload measures. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 2020, 21, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causse, M.; Chua, Z.; Peysakhovich, V.; Del Campo, N.; Matton, N. Mental workload and neural efficiency quantified in the prefrontal cortex using fNIRS. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, B.Z.; Neuper, C. Could anyone use a BCI. In Brain-Computer Interfaces: Applying our Minds to Human-Computer Interaction; Tan, D.S., Nijholt, A., Eds.; Springer: London, 2010; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cheveigné, A.; Di Liberto, G.M.; Arzounian, D.; Wong, D.D.; Hjortkjær, J.; Fuglsang, S.; Parra, L.C. Multiway canonical correlation analysis of brain data. NeuroImage 2019, 186, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Machine learning for precision psychiatry: Opportunities and challenges. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.B.; Falkai, P.; Koutsouleris, N. Machine learning approaches for clinical psychology and psychiatry. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2018, 14, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cearns, M.; Hahn, T.; Baune, B.T. Recommendations and future directions for supervised machine learning in psychiatry. Translational Psychiatry 2019, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, G.; Monaro, M.; Conversano, C.; Gemignani, A.; Sartori, G. Machine learning in psychometrics and psychological research. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 10, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lashgari, E.; Liang, D.; Maoz, U. Data augmentation for deep-learning-based electroencephalography. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2020, 346, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, J.J.; Pritchard, M.; Fratini, A.; Ekárt, A.; Faria, D.R. Synthetic biological signals machine-generated by GPT-2 improve the classification of EEG and EMG through data augmentation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2021, 6, 3498–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, R.A.; Colombini, E.L. Parkinson’s disease EMG data augmentation and simulation with DCGANs and Style Transfer. Sensors 2020, 20, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.B.; Bjaalie, J.G.; Das, S.; Egan, G.F.; Ghosh, S.S.; Goscinski, W.J.; Grethe, J.S.; Kotaleski, J.H.; Ho, E.T.W.; Kennedy, D.N.; Lanyon, L.J.; Leergaard, T.B.; Mayberg, H.S.; Milanesi, L.; Mouček, R.; Poline, J.B.; Roy, P.K.; Strother, S.C.; Tang, T.B.; Tiesinga, P.; Wachtler, T.; Wójcik, D.K.; Martone, M.E. A standards organization for open and FAIR neuroscience: The international neuroinformatics coordinating facility. Neuroinformatics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lühmann, A.; Boukouvalas, Z.; Müller, K.R.; Adalı, T. A new blind source separation framework for signal analysis and artifact rejection in functional near-infrared spectroscopy. NeuroImage 2019, 200, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.; Fekete, T.; Gal, K.; Shriki, O. EEG-based prediction of cognitive load in intelligence tests. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2019, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, A.; Ihme, K.; Jipp, M.; Rieger, J.W. Assessing the driver’s current level of working memory load with high density functional near-infrared spectroscopy: A realistic driving simulator study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2017, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pacios, J.; Garcés, P.; del Río, D.; Maestú, F. Tracking the effect of emotional distraction in working memory brain networks: Evidence from an MEG study. Psychophysiology 2017, 54, 1726–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C. Prefrontal and parietal contributions to spatial working memory. Neuroscience 2006, 139, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Vázquez, P.; Gail, A. Directed interaction between monkey premotor and posterior parietal cortex during motor-goal retrieval from working memory. Cerebral Cortex 2018, 28, 1866–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, P.; Raes, A.; Morton, J.; Bombeke, K.; Van Acker, B.B.; Larmuseau, C.; Depaepe, F.; Van den Noortgate, W. Towards measuring cognitive load through multimodal physiological data. Cognition, Technology & Work 2021, 23, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.F.; Epps, J.; Ambikairajah, E.; Choi, E.H. Voice source under cognitive load: Effects and classification. Speech Communication 2015, 72, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, G.; Cabrall, C.; de Winter, J. Review of eye-related measures of drivers’ mental workload. Procedia Manufacturing 2015, 3, 2854–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottemukkula, V.; Derakhshani, R. Classification-guided feature selection for NIRS-based BCI. Proceedings of the 5th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering 2011, 2011, pp. 72–75 Journal Abbreviation: 2011 5th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.A. Subject-Specific feature selection for near infrared spectroscopy based brain-computer interfaces. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 195, 105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Aich, S.; Joo, M.i.; Sain, M.; Kim, H.C. A multichannel convolutional neural network architecture for the detection of the state of mind using physiological signals from wearable devices. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2019, 2019, 5397814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgher, U.; Khalil, K.; Khan, M.J.; Ahmad, R.; Butt, S.I.; Ayaz, Y.; Naseer, N.; Nazir, S. Enhanced accuracy for multiclass mental workload detection using long short-term memory for brain–computer interface. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2020, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modality | Features |

|---|---|

| Brain Activity | Mean, standard deviation, peak-to-peak (PTP) amplitude, skewness, and kurtosis of the 82 optical channels |

| Physiology | |

| Heart Rate | Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of heart rate |

| Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of heart rate variability | |

| Respiration | Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of respiration rate |

| Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of respiration amplitude | |

| Temperature | Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of body temperature |

| Ocular Measures | |

| Fixations | Number of fixations, total duration and average duration of fixations, and standard deviation of the duration of fixations |

| Pupillometry | Mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of pupil dilation |

| Performance | Average reaction time and cumulative accuracy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).