1. Introduction

Early adolescence is characterized by a multitude of changes taking place at the physical, emotional, cognitive, and social level and which involve multiple socio-developmental domains [

1,

2]. From the family which represents one of the first socialization contexts [

3,

4], to more proximal groups like peers (i.e., friends and classmates) [

6] and other adults (i.e., teachers) [

7], the quality of relationships that adolescents develop within and between these systems can highly influence their sense of self, their perceptions about life, their affective experiences, and their sense of subjective well-being. Subjective well-being is widely considered as a core indicator of adolescents’ adjustment [

8]. It comprises cognitive components reflecting satisfaction with life (as perceived both globally and with reference to specific life domains), as well as affective components that refer to the presence of positive and absence of negative emotional experiences [

9].

Thus far, little systematic research has been conducted on the role of supportive relationships with proximal socialization agents (i.e., parents, teachers, and peers) on specific components of subjective well-being, including both cognitive and affective dimensions. Moreover, whether and how supportive relationships within these socialization contexts can differentially relate to adolescents’ global (context-free) and domain-specific perceptions of their lives has not yet been systematically examined. By adopting a social-psychological perspective, we consider adolescent well-being as a multifaceted construct embedded in family, school and peer socialization contexts and disentangle relations of these contexts with specific well-being components. More specifically, we test the association between three sources of support (parents, teachers, and peers) and specific components of subjective well-being (cognitive, affective, global, and domain-specific) to determine whether there is a functional specialization of the role that these crucial socialization agents play for adolescents to attain well-being in specific life domains. We advance current literature by contributing to a more nuanced understanding of subjective well-being in early adolescents and elucidating the crucial role of parents, teachers, and peers in this regard.

1.1. Adolescent well-being as embedded in family, school, and peer socialization contexts

Consistent with developmental perspectives, social–psychological literature highlights the importance of investigating adolescents’ development within family, school, and peer socialization contexts [

2,

10,

11]. The family represents the first micro-system in which individual development occurs [

12] and it greatly impacts one’s experiences with other proximal (e.g., peer groups, school contexts) and more distal systems. Parents can deeply affect adolescents’ harmonious development by acting as modelling agents [

2,

4] and by forming high-quality relationships, which provide adolescents with a “secure basis” for feeling safe and making autonomous choices and decisions [

5,

13]. Furthermore, positive relationships with parents are crucial for the development of individual and social competencies such as emotion regulation and empathy which are essential for psychosocial well-being across the life course of an individual and even more so in the early developmental stages (see for a review [

14]. Especially during early adolescence, the support of parents and main caregivers is fundamental for youngsters to enhance their self-worth, as well as their mental and physical well-being (for an overview, see [

15,

16]. Moreover, lower levels of parental support have been associated with general psychological distress and emotion regulation difficulties [

17].

Beyond the family, school is one of the most important socialization contexts for early adolescents as it provides a rich array of opportunities to interact with adults and peers in a structured educational setting [

18,

19]. Teachers are the most frequently reported positive role models [

20] or trusted adults in early adolescents’ lives, apart from primary caregivers. Research shows that supportive relationships between students and their teachers positively influence school engagement and achievement, social skills and problem-solving, and sense of purpose and autonomy in early adolescents [

21,

22]. Moreover, the quality of teacher-student relationship is reflected in adolescents’ perceptions of safety in the school environment [

23], which is found to be closely related to general feelings of satisfaction with school [

24]. Considering that the school represents one of the most relevant life domains for early adolescents, perceptions of satisfaction with life as a student and the things students learn in the school environment are an important part of adolescent well-being. In this line, a study [

25], conducted on data from the Children's Worlds Survey found that satisfaction with school was consistently related to subjective well-being in early adolescents from 11 countries.

While adolescents interact with their parents mostly at home and with their teachers at school, their relationships with their peers span both inside and outside school and home environments [

1]. In early adolescence, young people increasingly spend time with their friends who become a primary source of intimacy and support (see [

26] for a review). Friendships, like family relationships, can deeply influence the development of adolescents’ identity by offering a safe interpersonal context in which adolescents can test and evaluate their identity choices through social comparison [

10,

27,

28,

29]. As adolescents experiment with different behaviors and self-presentation strategies, receive informative feedback from one another, and benefit from social comparison processes, the quality of relationships with friends may significantly impact their self-worth and subjective well-being (for a review see [

30]). It has been consistently shown that positive relationships with friends and peers have positive effects on self-esteem, psychosocial well-being, and satisfaction with school in early adolescents [

31]. Moreover, the need to be accepted by peers along with the first love relationships may alter the emotional balance at this age, which predisposes adolescents to experience strong positive and negative emotions [

32]. Focusing on the role of peers within the school context, support from classmates (as an important reference group in the peer context) [

27] has been shown to be related to lower levels of anxiety and high academic performance [

33], lower levels of loneliness and higher school satisfaction [

34] among early adolescents. In sum, quality relationships with peers at school influence whether students experience positive emotions at school, how they adjust to negative experiences, whether they feel they belong, whether they are satisfied with school life in general, as well as their sense of subjective well-being. In particular, friendships that adolescents create with peers at school are found to be relevant for students’ feelings of self-worth [

35], which is an important predictor of subjective well-being.

1.2. Who matters the most? The differential associations between parents, teachers, and peers’ support and adolescents’ well-being

Currently, a large evidence base shows that positive relationships with parents and teachers as well as with peers make early adolescents feel supported and this is positively related to adolescent well-being during this developmental stage. However, empirical studies on the role these distinct socialization contexts may play on adolescent well-being have either investigated these contexts separately, considering single aspects of well-being (e.g., physical, or mental health) or using different operationalizations of well-being to include behavioral, cognitive, socioemotional and/or academic performance outcomes. Moreover, very few studies have examined the differential relation of parental, teacher and peer support on subjective well-being indicators testing their combined effects within the same model.

For instance, Walsh and colleagues [

35] examined the association of the role of parents (such as monitoring, involvement and support at school), teachers (support at school) and peers (excess time spent with friends, peer rejection at school) with risk behaviors (such as smoking and drinking) and psychological well-being (measured by items such as ‘irritability or bad temper’, ‘feeling nervous’, ‘difficulties in getting to sleep?’) among Israeli-born and immigrant adolescents of 11 – 15 years old. They found that the supportive role of the three socialization agents (parents, teachers, and peers) was related with high levels of well-being and low levels of risk behaviors at school. More recently, Butler and colleagues [

37] examined the association between the level of family adult support, school adult support, and school peer support and mental well-being in adolescents aged 8-15 years old from UK. Results showed that all three sources of support were independently and equally associated with mental well-being. While these studies provide evidence of an equivalent level of association between support from parents, teachers and peers and adolescent well-being indicators, other research offers more mixed results. For instance, Hoferichter and colleagues [

38] investigated the relations between parental, teacher and peer support and physical well-being (measured by items such as ‘I have felt sick’), psychological well-being (measured by items such as i.e., ‘I was afraid’, ‘I laughed a lot’) and self-worth (measured by items such as ‘I was proud of myself’). Results showed parental support was associated with high levels of physical and psychological well-being and self-worth, teacher support was associated with high levels of physical well-being and feelings of self-worth, whereas peer support was associated with high levels of psychological well-being only.

It should be noted that, while the evidence base on the differential relations between parental, teacher and peer support and adolescent well-being is thin, the inconsistencies in existing findings might reflect conceptual and methodological differences among the various studies in which different indicators of well-being (e.g., physical, psychological, mental well-being) were examined and different supportive roles of reference figures (e.g., parents, teachers, peers) were tested. Moreover, contextual characteristics and age-group differences might further account, albeit partly, for the variance in these results. Systematic research on the different sources of support and their differential relations with specific components of subjective well-being is still lacking. From a socio-psychological perspective, it is important to determine whether and to what extent supportive relations from adults and peers in proximal socialization contexts are related to cognitive and affective components of well-being and especially whether adolescents’ global (context-free) and domain-specific perceptions of their lives are differentially associated with the quality of supportive relationships with significant others within these systems.

1.3. The present study

The present study examines whether and to what extent supportive relationships with proximal socialization agents like parents, teachers and peers are differentially associated with cognitive and affective components of subjective well-being. Moreover, we investigate whether supportive relationships within these proximal socialization systems are associated in a differential way with adolescents’ global (context-free) and domain-specific perceptions of satisfaction with life. As noted by researchers [

39], the simultaneous measurement of global (context-free) and more specific (domain-based) perceptions of satisfaction with one’s life contributes to a more nuanced understanding of adolescent well-being and more accurately captures the complexity of the concept, especially in young age groups. Thus, the present study extends existing knowledge in this domain by examining associations between support from three crucial socialization agents (i.e., parents, teachers, peers) and specific components of adolescents’ subjective well-being (context-free, domain-based, cognitive, affective). In addition, it provides much needed evidence from a less researched context like Albania.

As suggested by theoretical frameworks and empirical findings reviewed above, we expect to find positive relations between the three sources of support (parents, teachers, and peers) and cognitive and affective components of adolescent subjective well-being. However, as parents, teachers and peers act as different socializing agents employing different methods, a functional specialization hypothesis can be made whereby support from these three sources may be differentially related to specific components of subjective well-being. On the one hand, the family’s role can be considered as a comprehensive one, with minor functional specialization. That is, parents are the primary caregivers and source of support, acting as primary role models, hence their efforts are concentrated into helping adolescents succeed in life and have a generally positive outlook. Therefore, parents’ support would be revealed in strong associations with both global cognitive and affective components of subjective well-being. On the other hand, teachers’ support may be circumscribed to the school context where teachers focus on assisting students to succeed academically and feel satisfied with life in school, therefore we can expect that teacher support be associated with high levels of satisfaction in the school domain. When it comes to peers, it has been amply demonstrated that they serve as the main source of social comparison in multiple life domains [

2,

4,

13]. Friends and classmates become increasingly influential in early adolescents’ life as adolescents benefit from social comparison processes and informative peer feedback concerning various domains of life. Moreover, social interactions with peers span both within and outside the school context, hence we expect supportive relationships with peers to be associated with higher levels of not just global (context-free) cognitive and affective components of well-being but also satisfaction with life in specific domains, including satisfaction with school.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

The study uses Albanian data from Wave 3 of the Children’s Worlds International Survey on Children’s Well-Being (see

www.isciweb.org), which is a large international study assessing children’s subjective perceptions and evaluations of their lives and well-being across different contexts and domains [

40]. Wave 3 of the survey was conducted in Albania in 2017 [

41]. It includes a representative school-based sample of 2,339 adolescents (age range 9-13 years; Mean age= 11.2, SD=20.4; girls = 1152, 49.3%). To ensure representativeness, schools in all 12 geographic regions of Albania were included. The sample was calculated using probability proportional to size and density approach. The schools were categorized by region, residence (urban or rural) and by size. A random selection of schools (67 schools in total) was invited to participate in the study and one class was selected per school, per target age group. The study procedure was explained by two trained interviewers who also supported children with any questions. No teachers were present in the classroom while the questionnaire was being filled out. Informed consent was obtained from all parents of prospective participants and ethics clearance was obtained by the Albanian Ministry of Education and Sports (Prot.No. 13113/1).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Proximal Socialization Contexts Variables

Three proximal socialization contexts were assessed. Items referring to the relationship with parents and caregivers at home were selected to tap on the family domain as adolescent’s primary socialization context. Then, items referring to participants’ relationship with teachers and with peers were selected as referring to the two most important secondary socialization contexts with adults and peers in early adolescents’ lives.

2.2.1.1. Supportive relationships with parents

Students’ perceptions of supportive relationships with parents were measured by six items tapping on care and support from parents, on feeling safe and on children’s views being listened to and respected at home. Students were asked to respond to items such as “If I have a problem, people in my family will help me” and “My parents/carers listen to me and take what I say into account” indicating the degree to which they agreed with each of the statements. Response categories included five Likert-type options, ranging from 0 (do not agree at all) to 4 (absolutely agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .67.

2.2.1.2. Supportive relationships with teachers

Perceptions that teachers are caring and supportive towards students and treat their views with respect were measured through five items. Students were asked to mark their agreement with statements, such as “If I have a problem at school my teachers will help me” and “My teachers listen to me and take what I say into account”. Response options ranged from 0 (do not agree at all) to 4 (absolutely agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .68.

2.2.1.3. Supportive relationships with peers

Perceptions of supportive relationships with peers were measured by six items related to students’ satisfaction with friends and classmates and the support they receive from them. Sample statements included “I am satisfied with my friends” and “If I have a problem, I have classmates who will support me”. Responses were given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (do not agree at all) to 4 (absolutely agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .72.

2.2.2. Subjective Well-being Variables

A multifaceted construct of subjective well-being was assessed, consisting of cognitive and affective components involved in the way that adolescents perceive and evaluate their lives [

39,

42]. The cognitive component includes both (a) global, context-free items assessing overall satisfaction with life and (b) domain-based items referring to satisfaction with life in specific life domains. The affective component of adolescent well-being is assessed through items taping on positive and negative affect.

2.2.3.1. Satisfaction with life (context-free)

Global perceptions of one’s satisfaction with life were measured using the Children’s Worlds Subjective Well-Being Scale (CW-SWBS) [

40], which is an adaptation of the Student Life Satisfaction Scale [

43] and measures context-free life satisfaction. It consists of six items that assess cognitive components of subjective well-being. Sample items include the following statements: “I enjoy my life,” “My life is going well,” “I like my life” and “I am happy with my life.” Response options were on a 11-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (do not agree at all) to 10 (totally agree) with higher scores indicating greater levels of satisfaction with life. Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was .86.

2.2.3.2. Satisfaction with life (domain-based)

Satisfaction with life in specific domains was measured using a series of statements that were adapted from the Brief Multidimensional Student Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) [

44]. It comprises 9 items, with each item representing adolescents’ satisfaction with a particular life domain. Sample items included “Satisfaction with the place you live”, “Satisfaction with the way you look”, “Satisfaction with the things you have” and “Satisfaction with how you use your time”. Participants were asked to indicate their responses on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all satisfied” (0) to “Totally satisfied” (10). Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was .78.

2.2.3.3. Satisfaction with school

School represents one of the most important life domains for early adolescents, hence we opted for separately assessing satisfaction with school from other life domains. Based on previous psychometric research using data from previous waves of the survey from 15 countries [

8], a two-item index was used, including (a) satisfaction with life as a student and (b) satisfaction with things learned, given the demonstrated high loadings of these two items on satisfaction with school cross-culturally. Students indicated their response on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all satisfied” (0) to “Totally satisfied” (10). Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was .67.

2.2.3.4. Affective subjective well-being

Affective well-being was measured through the Children’s Worlds Positive and Negative Affect Scale (CW-PNAS), which is based on Russel’s Model of Core Affect [

45]. Participants reported the extent to which they experienced three positive (happy, calm, and full of energy) and three negative (sad, stressed, and bored) affective states over the last 2 weeks. Responses were given on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “Extremely” (10). Three affective balance items were obtained by subtracting negative from positive affect scores. Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was .80.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Version 24.0 for Windows. Regression analyses regarding the main aim of this study were conducted in Mplus 8.7 [

46] using Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimator [

47], which considers potential non-normality as well as non-independence of observations which emerge due to the clustered nature of our sample. In a first step, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to specify the latent variables and to examine the initial measurement model. To explore the theorized relationships between the supportive relationships with significant others in the three socialization contexts and subjective well-being, a structural equation model (SEM) was subsequently specified. In this model, well-being variables (i.e., cognitive context-free and domain-based life satisfaction, satisfaction with school and affective well-being) were regressed on the predictor variables (i.e., parental support, teacher support, peer support). The Wald test was used to identify possible significant differences in paths and effects across the three socialization contexts. The Wald-based statistics test the hypothesis that two regression paths or the same regression path across two groups are significantly different compared to the null hypothesis of path equivalence [

48].

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Table 1 shows all descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, standard deviation, range, skewness, kurtosis) and correlations of the variables of interest. As expected, the correlation matrix revealed significant positive correlations between all variables of interest.

3.2. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

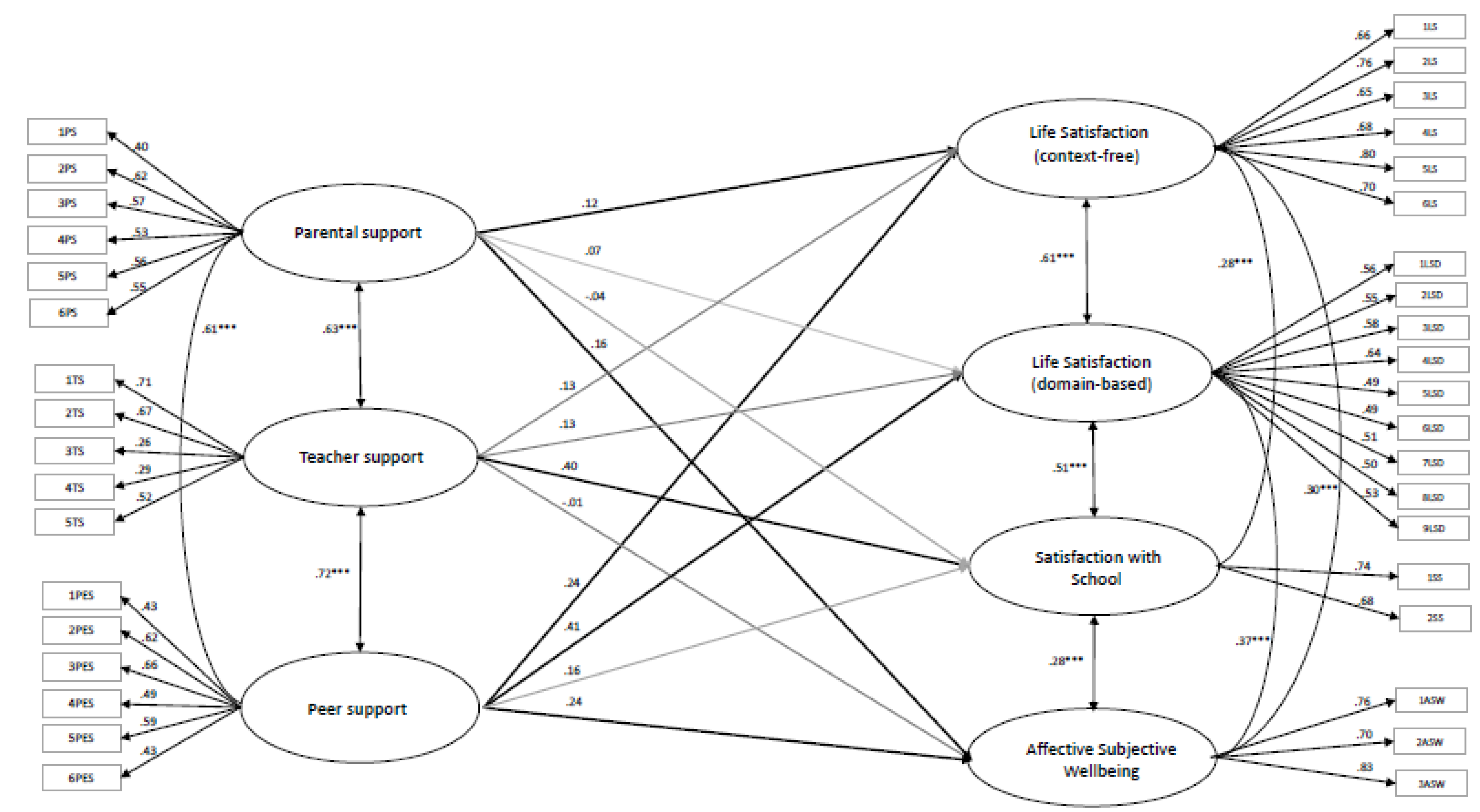

The specified SEM achieved an adequate fit for our dataset, χ2(606) = 1305.815, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.022 (90% CI [0.021 0.024]), CFI = 0.930, TLI = 0.923, SRMR = 0.037. As can be seen in

Figure 1, the standardized factor loadings of all latent variables ranged between 0.40 and 0.88 (with the exceptions of two items with lower loadings on “teacher support”). This model also included correlations between the predictor variables: Parental support was positively associated with teacher support (r = 0.63, p < 0.001) and with peer support (r = 0.61, p < 0.001). Moreover, peer and teacher support were strongly and positively associated (r = 0.72, p < 0.001). The residual correlations of the dependent variables were also significantly associated: global (context-free) life satisfaction was positively associated with domain-based life satisfaction (r = 0.61, p < 0.001), satisfaction with school (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and affective subjective well-being (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). Likewise, affective well-being was significantly associated and satisfaction with school (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and domain-based satisfaction with life (r = 0.37, p < 0.001).

As can be seen in

Figure 1 and Table 2, significant relations were found between peer support and almost all well-being variables in our dataset: global (context-free) life satisfaction (β = 0. 24, p < 0.001); domain-based life satisfaction (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and affective subjective well-being (β = 0.24, p < 0.001). A trend to significance was evidenced in the path from peer support to satisfaction with school (β = 0.16, p = 0.058). These significant effects indicate that students who report high support by their friends and classmates also report high values of satisfaction with life either globally perceived or based on specific domains, including satisfaction with school and affective well-being. Parental support was significantly related to global cognitive and affective well-being variables. That is, adolescents who feel supported by their parents are more likely to report higher levels of satisfaction with their lives globally perceived (β = 0.12, p < 0.029) and are more likely to report higher affective balance (β = 0.16, p = 0.002). Lastly, the path from teacher support to satisfaction with school was significant (β = 0.40, p < 0.001). Accordingly, students who received high levels of teacher support reported higher satisfaction with school. All other paths did not reach significance levels.

A comparison of the regression paths on satisfaction with school did not find any differences (Wald = 1.875, p =.170) between paths from peer (β =.16) and teacher support (β =.40). Similarly, results of the path analyses on satisfaction with life (context-free) indicated that the relation between support from peers (β =.24) and support of family members (β =.12) was not significantly different (Wald = 0.766, p = .381). Same for the relations between peer (β =.22) and parental support (β =.16) and affective subjective well-being (Wald = 0.411, p = 0.521).

4. Discussion

The present study examined the associations between supportive relationships with proximal socialization agents (i.e., parents/primary caregivers, teachers, and peers) and cognitive and affective components of subjective well-being in early adolescents. Moreover, the differential relations of these three sources of support with adolescents’ satisfaction with their lives as perceived globally and with reference to specific life domains was modelled. While confirming our general expectations regarding the positive relations between support from parents, teachers and peers and well-being components, our findings offer support for a functional specialization hypothesis according to which parents, teachers, and peers act as different socialization agents. Hence, there is a differential association between support received from these three sources and specific components of adolescent subjective well-being.

We found that supportive relationships with parents were significantly related to both global cognitive and affective components of subjective well-being, so that adolescents that felt more supported by their family or primary caregivers also reported higher levels of satisfaction with their lives in general and higher levels of affective balance. This is in line with previous research demonstrating the importance of parents as the primary caregivers and socialization agents for a range of developmental and well-being indicators in adolescence [

2]. Parents are the primary source of care and support, and a robust body of research has shown the importance of caring, supportive families in protecting against the toxic effects of stress especially when adolescents must face difficult situations, and in fostering adolescents’ resilience and emotional regulations skills [

37]. Hence, quality relationships within the family will reflect in global perceptions of satisfaction with one’s life as well as in a higher affective balance. We did not find a significant relationship between parental support and domain-specific satisfaction with life and satisfaction with school. This can be attributed to the fact that early adolescents may perceive support from their parents as most fundamental for their overall emotional well-being and global satisfaction with their lives, whereas other socializing agents (e.g., peers) may become increasingly more important for drawing specific feedback through social comparison processes, especially in specific life domains (such as ‘how one looks’, ‘how one spends free time’ and so on).

Similarly, adolescents’ perceptions of satisfaction with school and their life as a student, are probably more influenced by their interactions with socializing agents in this particular setting, namely teachers and peers, rather than with parents. Indeed, in line with our expectations, we found that supportive relationships with teachers were associated with higher levels of satisfaction with school, which is in conformity with studies highlighting the role of teachers’ support in assisting students to succeed academically and feel satisfied with life in school. Differently from other studies [

38] however, we found that the association of supportive relationships with teachers and adolescent subjective well-being is circumscribed to the school context, supporting a functional specialization of relationships with different socializing agents’ hypothesis.

The most influential socializing agent in our study was the group of peers, including friends and classmates whose supportive relationships were reflected not only in high levels of global cognitive and affective components of adolescent well-being but also in adolescents’ satisfaction with life in specific domains, including satisfaction with school. This is in line with a great body of research demonstrating the increasing influence of relationships with peers in early adolescents’ life. Indeed, from early to middle adolescence, parent–adolescent relationships become more egalitarian, whereas peer influences increase [

50,

51] as adolescents spend more time with their friends and classmates and become an important reference group in the peer context as well as an important source of intimacy, support, and safety [

20,

26,

27]. In a stage in which youngsters need to be accepted by their peer group, the support of this group heavily impacts their perceptions about themselves, their self-image, their perception of their life and thus specific domains of life satisfaction [

25,

49]. Moreover, as adolescents’ interactions with peers span both within and outside the school context, it is not surprising that supportive relationships with friends and classmates can be associated with high levels of satisfaction with school, which is in line with previous research on the importance of positive relationships with classmates on a range of school-related outcomes including school satisfaction [

8]. These findings are in line with research showing the importance of school-based peer support programs which are most effective in strengthening social and emotional regulation and enhancing subjective well-being in early adolescents [

52].

It should be noted however, that although we found peer support to be strongly related to almost all components of subjective well-being under investigation, these associations were not significantly different from those found between parental support (on context-free satisfaction with life and affective balance) and teachers (i.e., satisfaction with school). This is in line with previous research in this area [

36,

37,

38], which demonstrates the importance of support from the three socialization agents in relation to specific components of adolescent well-being.

4.1. Strengths, limitations, and suggestions for future research

One of the strengths of the present work is that it takes a socio-psychological perspective to the analysis of adolescent well-being using data from an international study (The Children’s Worlds International Survey conducted on more than 35 countries worldwide). Moreover, we focus on data from a specific and less researched country context, such as that of Albania, offering insights into the role that specific socialization contexts may have on early adolescent well-being in transitioning societies [

53]. Our findings contribute to gaining a more nuanced understanding of the relations between supporting relationships with socialization agents in proximal systems and subjective well-being indicators in a representative cohort of 9–13-year-olds. Nevertheless, our findings should be considered in the light of certain limitations. First, being based on cross-sectional data, our findings offer a snapshot picture of the associations between supportive relationships with different socializing agents (parents, teachers

, and peers) and specific components of adolescent well-being at a given moment in time. Early adolescence is a life stage that’s characterized by a multitude of changes taking place at the physical, emotional, cognitive, and social level which are influenced by and in turn mutually influence the relationships adolescents develop with others (parents, teachers, peers) in proximal socializing contexts [

1,

2]. Hence, the dynamics of the interrelationships between supportive relationships with these socializing agents and adolescent well-being indicators as they unfold through time was not captured as it was beyond the scope of the present paper. Similarly, we did not investigate potential mediating factors that could account for the differential impact of these sources of support on specific well-being components. Moreover, our data may be limited to the specific age-range (9-13 years old) of our participants and more research may be needed to examine whether and how the impact of different socialization agents on subjective well-being components changes in different developmental stages, from early to late adolescence. Thus, future research should adopt a longitudinal approach to examining these issues as they unfold through time and adopting a cross-cultural perspective. Furthermore, analyzing data from different country contexts would elucidate the role of socio-cultural factors in accounting for country-specific differences in the functional specialization hypothesis tested in this study.

5. Conclusions

The current findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the associations between supportive relationships with adults and peers in adolescents’ proximal socialization contexts (i.e., family, school, peer groups) and adolescent subjective well-being. Given that subjective well-being is a multifaceted concept that encompasses both cognitive and affective components and includes perceptions and evaluations of one’s life both globally perceived (context-free) and as referring to more specific life domains, elucidating the relations with parent, teacher and peer support highlights the specific role that these important socialization agents may play in adolescents’ satisfaction with life in different domains. Subjective well-being has been shown to positively affect both physical and mental health, albeit this relationship has been examined less across the lifespan and in the adolescent population [

37,

54]. Children and adolescents account for a large proportion of the burden of health and mental health problems globally, and poor mental health in early adolescence is a predictor of mental disease in adults [

55]. Hence, the key to achieving the SDG Goal 3 of ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all at all ages could be preventing mental health problems in adolescence. Our findings contribute to advancing current literature in this domain by informing research and practice in terms of the positive role that supportive relationships with parents, teachers and peers may play in specific components of subjective well-being in early adolescents. They highlight the need to sustain adolescent well-being through reinforcing positive, trusting relationships amongst peers and between adolescents and teachers and parents, as a priority to raising todays and future’s healthy individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F., and M.R.; formal analysis, E.F., and E.C.; investigation, E.F., and M.K.; data curation, M.K., and E.F; writing—original draft preparation, E.F.; writing—review and editing, E.F., M.R., E.C., and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Albanian Ministry of Education.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all school personnel (teachers, directors and staff), as well as to children and parents for their support in the process of data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. Readings on the development of children. 2. Readings on the development of children (pp. 37–43).

- Crocetti, E. , Albarello, F., Meeus, W., & Rubini, M. (2022). Identities: A developmental social-psychological perspective. European Review of Social Psychology,1-41.

- Crocetti, E. , Branje, S., Rubini, M., Koot, H., & Meeus, W. (2017). Identity processes and parent-child and sibling relationships in adolescence: A five-wave multi-informant longitudinal study. Child Development, 88(1), 210–228. [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E. , Rubini, M., Branje, S., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2016). Self-concept clarity in adolescents and parents: A six-wave longitudinal and multi-informant study on development and intergenerational transmission. Journal of Personality, 84(5), 580–593. [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E. (2017). Identity formation in adolescence: The dynamic of forming and consolidating identity commitments. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 145–150. [CrossRef]

- van Doeselaar, L. , McLean, K.C., Meeus, W. et al. Adolescents’ Identity Formation: Linking the Narrative and the Dual-Cycle Approach. J Youth Adolescence 49, 818–835 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Suldo S., M. , Shaffer E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37, 52-68.

- Casas, F. , and González, M. (2017). School: One world or two worlds? Children’s perspectives. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 80, 157–170. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2009). “Subjective well-being,” in The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener, ed. E. Diener (New York: Springer), 11–58.

- Crocetti, E. (2018). Identity dynamics in adolescence: Processes, antecedents, and consequences. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(1), 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Ward, C. , & Geeraert, N. (2016). Advancing acculturation theory and research: The acculturation process in its ecological context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. , & Morris, P. A. (2006). The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Crocetti, E. , Rubini, M., & Meeus, W. (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Boele S, Van der Graaff J, de Wied M, Van der Valk IE, Crocetti E, Branje S. Linking Parent-Child and Peer Relationship Quality to Empathy in Adolescence: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Jun;48(6):1033-1055. [CrossRef]

- Cripps, K. , & Zyromski, B. (2009). Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being and Perceived Parental Involvement: Implications for Parental Involvement in Middle Schools. RMLE Online, 33, 1 - 13.

- Thomas PA, Liu H, Umberson D. Family Relationships and Well-Being. Innov Aging. 2017 Nov;1(3):igx025. Epub 2017 Nov 11. PMID: 29795792; PMCID: PMC5954612. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L. M. , & Demaray, M. K. (2007). Social support as a moderator between victimization and internalizing-externalizing distress from bullying. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 383.

- Eccles, J. S & Roeser, R.W (2011) Schools as Developmental Contexts During Adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. [CrossRef]

- Karataş, S. , Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., & Rubini, M. (2020). Understanding adolescents’ acculturation processes: New insights from the intergroup perspective. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2020(172), 53–71. [CrossRef]

- E. Brey, K. E. Brey, K. Pauker (2019) Teachers’ nonverbal behaviors influence children’s stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 188 (2019), pp. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. , Witt, P. L., & Wheeless, L. R. (2006). The role of teacher immediacy as a motivational factor in student learning: Using meta-analysis to test a causal model. Communication Education, 55(1), 21–31.

- Morrison, G.M. , & Allen, M.R. (2007). Promoting Student Resilience in School Contexts. Theory Into Practice, 46, 162 - 169.

- Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Sacco, F. C. (2004). The role of the bystander in the social architecture of bullying and violence in schools and communities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036(1), 215–23.

- Wang, M. T. , & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895.

- Lawler, M. J. , Newland, L. A., Giger, J. T., Roh, S., & Brockevelt, B. L. (2016). Ecological, relationship-based model of children’s subjective well-being: Perspectives of 10-yearold children in the United States and 10 other countries. Child Indicators Research, 1(10), 1–18.

- Brown, B. B. , & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development (pp. 74–103). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Albarello F, Crocetti E, Rubini M. I and Us: A Longitudinal Study on the Interplay of Personal and Social Identity in Adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2018 Apr;47(4):689-702. Epub 2017 Nov 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C. , & Geeraert, N. (2016). Advancing acculturation theory and research: The acculturation process in its ecological context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- van Doeselaar, L. , Meeus, W., Koot, H. M., & Branje, S. (2019, July 29). The Role of Best Friends in Educational Identity Formation in Adolescence. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A. L. , Yunes, M. Â. M., Nascimento, C. R. R., et al. (2021). Children’s Subjective Well-Being, Peer Relationships and Resilience: An Integrative Literature Review. Child Ind Res, 14, 1723–1742. [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. R. , Sarriera, J. C., & Bedin, L. M. (2018). Subjective well-being, life satisfaction and interpersonal relationships associated to socio-demographic and contextual variables. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13, 1–17.

- Gugliandolo, M. C. , Costa, S., Cuzzocrea, F., Larcan, R., & Petrides, K. V. (2015). Trait emotional intelligence and behavioral problems among adolescents: A cross-informant design. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 16–21. [CrossRef]

- Hoferichter, F. , & Raufelder, D. (2015). Examining the role of social relationships in the association between neuroticism and test anxiety—Results from a study with German secondary school students. Educational Psychology, 35(7), 851–868. [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M. , & Thijs, J. (2002). School satisfaction of elementary school children: The role of performance, peer relations, ethnicity and gender. Social Indicators Research, 59, 203–228.

- Maunder, R. , & Monks, C. P. (2019). Friendships in middle childhood: Links to peer and school identification, and general self-worth. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 37(2), 211–229. [CrossRef]

- Walsh SD, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H. Parents, teachers and peer relations as predictors of risk behaviors and mental well-being among immigrant and Israeli born adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Apr;70(7):976-84. [CrossRef]

- Butler N, Quigg Z, Bates R, Jones L, Ashworth E, Gowland S, Jones M. The Contributing Role of Family, School, and Peer Supportive Relationships in Protecting the Mental Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents. School Ment Health. 2022;14(3):776-788. Epub 2022 Feb 6. PMID: 35154501; PMCID: PMC8818094. [CrossRef]

- Hoferichter F, Kulakow S and Hufenbach MC (2021) Support from Parents, Peers, and Teachers Is Differently Associated With Middle School Students’ Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 12:758226. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. , and Biswas-Diener, R. (2000). New directions in subjective well-being research: The cutting edge. Ind. J. Clin. Psychol. 27, 21–33.

- Rees, G. , Savahl, S., Lee, B. J., and Casas, F. (eds) (2020). Children’s views on their lives and well-being in 35 countries: A report on the Children’s Worlds project, 2016-19. Germany: Children’s Worlds Project (ISCWeB).

- Kapllanaj, M. , Sianko, N., and Gjedia, R. (2022) Exploring After-School Activities by Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Subjective Well-Being. In H. Tiliouine et al. (eds.), Handbook of Children’s Risk, Vulnerability and Quality of Life, International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575. [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychol. Int. 12, 231–240.

- Seligson, J. L. , Huebner, E. S., and Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary validation of the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Soc. Indicat. Res. 61, 121–145. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, F. L., and Russell, J. A. (1998). Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 74, 967–984.

- Muthén L., K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2022). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Author.

- Satorra, A. , & Bentler, P. M. (2010). Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika, 75(2), 243–248. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley & Sons. [CrossRef]

- Casas F., Malo S., Bataller S., González M., Figuer C. (2009, July). Personal well-being among 12- to 18-year-old adolescents and Spanish university students, evaluated through the Personal Well-being Index (PWI). Paper presented at the meeting of the International Society for Quality of Life Studies, Florence, Italy.

- De Goede, I. H. A. , Branje, S. J. T., Delsing, M. J. M. H., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2009). Linkages over time between adolescents' relationships with parents and friends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(10), 1304–1315. [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, R. , & Laninga-Wijnen, L. (2022). The prominence of peer interactions, relationships, and networks in adolescence and early adulthood. In L. J. Crockett, G. Carlo, & J. E. Schulenberg (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent and Young Adult Development. American Psychological Association.

- King T, Fazel M. Examining the mental health outcomes of peer-led school-based interventions on young people aged between 4 and 18 years old: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2019 Apr 26;8(1):104. PMID: 31027512; PMCID: PMC6486684. [CrossRef]

- Sianko, N. , Small, M. A., Kapllanaj, M., Fino, E., & Mece, M. (2021). Who will sustain a culture of democracy in post-communist states? Examining patterns of democratic competence among youth in Albania and Belarus. Social Indicators Research. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, A. L. , Hansen, C. D., & Andersen, J. H. (2022). The association between perceived social support in adolescence and positive mental health outcomes in early adulthood: a prospective cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(3), 404-411.

- United Nations. (2018, May 03). Mental health 'neglected issue' but key to achieving Global Goals, say UN chiefs. (United Nations). Available online: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2018/05/mental-health-neglected-issue-butkey-to-achie ving-global-goals-say-un-chiefs/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).