Submitted:

19 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

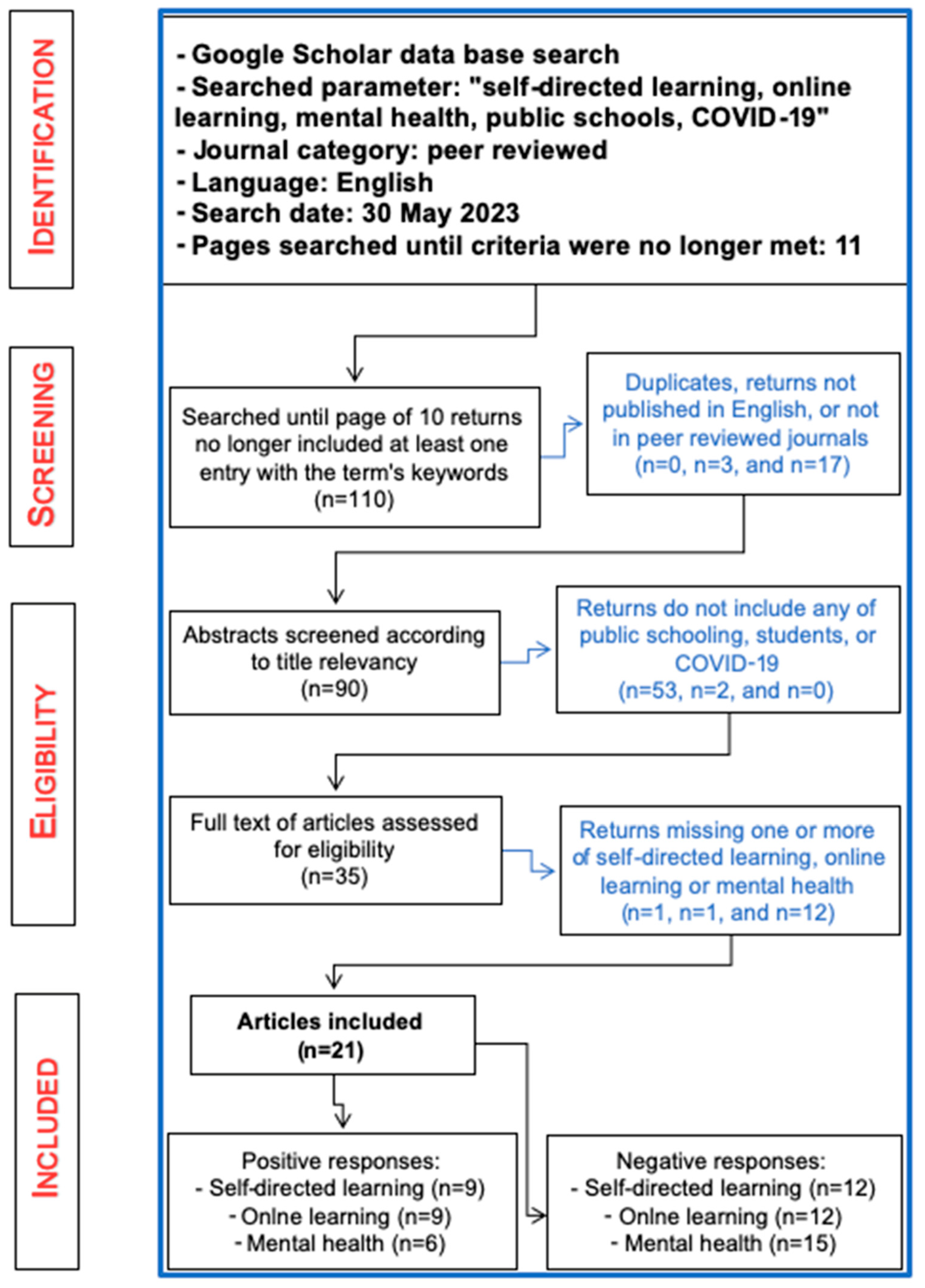

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Positive and/or Negative Assessmenst for Each of the Three Variables

4.1.1. All Positive

4.1.2. Two Positive, One Negative

4.1.3. One Positive, Two Negative

4.1.4. All Negative

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benton, T.D.; Boyd, R.C.; Njoroge, W.F. Addressing the global crisis of child and adolescent mental health. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. The WHO special initiative for mental health (2019–2023): universal health coverage for mental health. WHO/MSD/19.1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28223 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, F. The health. In The Frontier of Education Reform and Development in China: Articles from Educational Research; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnafors, S.; Barmark, M.; Sydsjö, G. Mental health and academic performance: a study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood. Soc. Psychia. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörberg Wallin, A.; Koupil, I.; Gustafsson, J.E.; Zammit, S.; Allebeck, P.; Falkstedt, D. Academic performance, externalizing disorders and depression: 26,000 adolescents followed into adulthood. Soc Psychia. Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019, 54, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguardia, A.; Pearl, A. Necessary Educational Reform for the 2lst Century: The Future of Public Schools in our Democracy. Urban Rev. 2009, 41, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Education as a Necessity of Life. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Education as Direction. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Education as Growth. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Preparation, Unfolding, and Formal Discipline. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. The Nature of Method. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Labor and Leisure. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Physical and Social Studies: Naturalism and Humanism. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Thinking in Education. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- .Dewey, J. Thinking in Education. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J. Teaching in the Nozw: John Dewey on the Educational Present; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Cultural reproduction. In Knowledge, Education, and Cultural Change, 1st ed.; Brown, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Urick, A. Cultural Reproduction Theory and Schooling: The Relationship between Student Capital and Opportunity to Learn. Amer. J. Educ. 2021, 127, 193–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, W. Introduction: A Public Education as Critical Aspirational Ideal. In What is a Public Education and Why We Need it: Philosophical Inquiry into Self-Development, Cultural Commitment, and Public Engagement; Lexington Books: London: UK, 2016; pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gutek, G.L. A History of the Western Educational Experience, 3rd ed.; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter, C.; Carmona, J.F. Un-standardizing curriculum: Multicultural teaching in the standards-based classroom, 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, S.J.; Woodcock, S.; Ehrich, J.; Bokosmaty, S. What are standardized literacy and numeracy tests testing? Evidence of the domain-general contributions to students’ standardized educational test performance. Brit. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 87, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. The Nature of Method. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Educational Values. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Intellectual and Practical Studies. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. The Individual and the World. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M.A.; Swennen, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education. Euro. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response. World Health Organization. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#! (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- World Health Organization. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. World Health Organization, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Duong, D. Endemic, not over: looking ahead to a new COVID era. CMAJ 2022, 194, E1358–E1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.E.; Spiro, D.J.; Viboud, C. Projecting the SARS-CoV-2 transition from pandemicity to endemicity: Epidemiological and immunological considerations. PLoS Patho. 2022, 18, e1010591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badlou, B.A. Post COVID-19 War Era, Covid-19 Variants Considerably Increased Hematologic Disorders. J. Intern. Med. Emerg. Res. 2023, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Enviro. 2023, 31, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Thurman, A. How Many Ways Can We Define Online Learning? A Systematic Literature Review of Definitions of Online Learning (1988–2018). Amer. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akabayashi, H.; Taguchi, S.; Zvedelikova, M. Access to and demand for online school education during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Int. J. Educ. Devel. 2023, 96, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Peng, L.; Jing, B.; Wu, C.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on User Experience with Online Education Platforms in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, L.; Wiley, K.; Debarger, A.H.; Bichler, S.; Bradford, A.; Linn, M.C. Self-directed Science Learning During COVID-19 and Beyond. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2022, 31, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, B.S.S.; Wicaksono, D. The implementation of self-directed learning strategy in teaching reading narrative text in distance learning during covid-19: a descriptive analysis study at the ninth-grade students of yadika 12 depok junior high school in academic year 2020/2021. Soc. Perspect. J. 2022, 1, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Wu, D.; Yang, H.H.; Guo, Q. Impact of information literacy, self-directed learning skills, and academic emotions on high school students’ online learning engagement: A structural equation modeling analysis. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R. Self-Directed Learning: Toward a Comprehensive Model. Adult Educ, Quart. 1997, 48, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S. Andragogy: Adult learning theory in perspective. Commun. Coll. Rev. 1978, 5, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeng, S. Various ways of understanding the concept of andragogy. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1496643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeng, S. Self-directed learning: A core concept in adult education. Educ. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, W.; Kirschner, D. Self-directed learning in video games, affordances and pedagogical implications for teaching and learning. Comp. Educ. 2020, 154, 103912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. Impact of smartphones on students: How age at first use and duration of usage affect learning and academic progress. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.M.M. Digital Literacy and Academic Performance of Students’ Self-Directed Learning Readiness. ELite J. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Lit. 2022, 2, 127–136. Available online: https://journal.unesa.ac.id/index.php/elite (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Kuntz, J.; Manokore, V. “I Did Not Sign Up For This”: Student Experiences of the Rapid Shift from In-person to Emergency Virtual Remote Learning During the COVID Pandemic. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2022, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathana, S.; Galdolage, B.S. The effect of Self-Directed Learning Motives and Students’ Cooperation on the success of Online Learning: The moderating effect of Resource Availability. J. Bus. Technol. 2023, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Nofal, M.; Akram, H.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Al-Okaily, M. Towards a Sustainable Adoption of E-Learning Systems: The Role of Self-Directed Learning. J. Inform. Technol. Educ. Res. 2022, 21, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Tasnim, S.; Sultana, A.; Faizah, F.; Mazumder, H.; Zou, L.; McKyer, E.L.J.; Ahmed, H.U.; Ma, P. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Research 2020, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andermo, S.; Hallgren, M.; Nguyen, T.T.D.; Jonsson, S.; Petersen, S.; Friberg, M.; Romqvist, A.; Stubbs, B.; Elinder, L.S. School-related physical activity interventions and mental health among children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med.-Open 2020, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, A.R.; May, T.; Dawes, J.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. ‘You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts’: a qualitative study about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among young people living in the UK. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053676–e053676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, K.; Arpaci, I. The role of self-directed learning, metacognition, and 21st century skills predicting the readiness for online learning. Contemp. Educ. Techn. 2021, 13, ep300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.R.; Golparvar, S.E. Modeling the relationship between socioeconomic status, self-initiated, technology-enhanced language learning, and language outcome. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 33, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, C.; Bouffard, T.; Vezeau, C.; Dussault, F. Does parental concern about their child performance matter? Transactional links with the student’s motivation and development of self-directed learning behaviors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 2, 1003–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Healey, R.L. Searching the Literature on Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL): An Academic Literacies Perspective: Part 1. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2023, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Wu, D.; Yang, H.H.; Guo, Q. Impact of information literacy, self-directed learning skills, and academic emotions on high school students’ online learning engagement: A structural equation modeling analysis. Educ. Inf. technol. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M.Y.; Zhu, M.; Bonk, C.J. Influence of self-directed learning on learning outcomes in MOOCs: A meta-analysis. Distance Educ. 2022, 44, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhou, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, W. Guiding teaching strategies with the education platform during the COVID-19 epidemic: Taking Guiyang No. 1 Middle School teaching practice as an example. Sci. Insigt. Educ. Front. 2020, 5, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.; Almerino, J.G.; Etcuban, J.O.; Gador, J.E.; Capuno, R.; Padillo, G.; Pepito, J. Mental Health Of High School Students In The New Normal Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Posit. School Psychol. 2022, 6, 2606–2626. Available online: https://journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/10267/6649 (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Ong, A.K.S.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Paruli, M.K.C.; Alejandro, T.M.; Parais, A.S.; Sarne, L.M.B. Factors affecting students’ happiness on online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A self determination theory approach. Inter. J. Inform. Educ. Technol. 2022, 12, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Challenges Identifying and Stimulating Self-Directed Learning in Publicly Funded Programs. In The Digital Era of Education: Novel Teaching Strategies and Learning Approaches Designed for Modern Students; Keator, C.S., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 259–300. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Carol-Nash/publication/346053184_Challenges_Identifying_and_Stimulating_Self-Directed_Learning_in_Publicly_Funded_Programs/links/6216ad1e82f54a53b1a7e812/Challenges-Identifying-and-Stimulating-Self-Directed-Learning-in-Publicly-Funded-Programs.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Schweder, S.; Raufelder, D. Adolescents’ expectancy–value profiles in school context: The impact of self-directed learning intervals. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwilestari, S.; Zamzam, A.; Susanti, N.W.M.; Syahrial, E. The Students’ Self-Directed Learning in English Foreign Language Classes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Lisdaya 2021, 17, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalo, F.K.B.; Reyes, V.P.; Bundalian, A.M.B. Challenges and opportunities in online distance learning modality in one public secondary school in the Philippines. IOER Int. Multidis. Res. J. 2022, 4, 89–99. Available online: https://www.ioer-imrj.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Challenges-and-Opportunities-in-Online-Distance-Learning-Modality-in-One-Public-Secondary-School-in-the-Philippines.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.; Lin, T.J.; Lonka, K. Motivating online learning: The challenges of COVID-19 and beyond. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.; Starkey, L.; Egerton, B.; Flueggen, F. High school students’ experience of online learning during Covid-19: the influence of technology and pedagogy. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 2021, 30, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, S.; Abd Aziz, N. COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Students’ Acceptance Towards Online Learning. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Law 2021, 24, 50–55. Available online: https://www.ijbel.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/IJBEL24.ISU-5-807.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J.; Nagy, R.P. Adaptability and high school students’ online learning during COVID-19: A job demands-resources perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 702163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Fut. 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacogue, S.M.S.; Protacio, A.V.; Alocada, J.J.S.; Gevero, G.A.T.; Diama, B.G.Y.; Denoy, D.L.; Lumasag, J.A.; Oronce, R.A., Jr. Learning in isolation: Exploring the lived experiences of students in self-directed learning in English. Globus J. Prog. Educ. 2022, 12, 81–84. Available online: https://globusedujournal.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/GE-121-JJ22-Stefi-Marie-S.-Tacogue.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Shepherd, H.A.; Evans, T.; Gupta, S.; McDonough, M.H.; Doyle-Baker, P.; Belton, K.L.; Karmali, S.; Pawer, S.; Hadly, G.; Pike, I.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on High School Student-Athlete Experiences with Physical Activity, Mental Health, and Social Connection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Hong, J.C.; Zhao, L. Impact of the self-directed learning approach and attitude on online learning ineffectiveness: The mediating roles of internet cognitive fatigue and flow state. Front. Pub. Health 2022, 10, 927454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K.N.; Carey, K.; Lincoln, E.; Shih, A.; Donalds, R.; Kessel Schneider, S.; Holt, M.K.; Green, J.G. School connectedness still matters: The association of school connectedness and mental health during remote learning due to COVID-19. J. Primary Prevent. 2021, 42, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, Q.; Hong, X. Implementation and Challenges of Online Education during the COVID-19 Outbreak: A National Survey of Children and Parents in China. Early Childhood Res. Quart. 2022, 61, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garris, C.P.; Fleck, B. Student evaluations of transitioned-online courses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scholar. Teach. Learn. Psychol. 2022, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina, I.Y.; Susilo, H. The impact of learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic on science literacy, social interaction, and digital literacy at Senior High School Palangkaraya City. Bio-Inoved J. Biologi-Inovasi Pendidikan 2022, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, S.R.; Hua, T.K.; Sultan, F.M.M. A comparison of online learning challenges between young learners and adult learners in ESL classes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A critical review. Theor. Prac. Lang. Stud. 2022, 12, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literat, I. “Teachers act like we’re robots”: TikTok as a window into youth experiences of online learning during COVID-19. AERA Open 2021, 7, 2332858421995537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yomoda, K.; Kurita, S. Influence of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity in children: A scoping review of the literature. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2021, 19, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuine, T.A.; Biese, K.M.; Petrovska, L.; Hetzel, S.J.; Reardon, C.; Kliethermes, S.; Bell, D.R.; Brooks, A.; Watson, A.M. Mental health, physical activity, and quality of life of US adolescent athletes during COVID-19-related school closures and sport cancellations: a study of 13 000 athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2021, 56, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A general model of cognitive bias in human judgment and systematic review specific to forensic mental health. Law and human behavior 2022, 46, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Research Topic on Public Schools Regarding COVID-19 | Self-Direction | Online Learning | Mental Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of information literacy | + | + | + |

| Motivating online learning | + | – | – |

| Learning in isolation | – | – | – |

| High school student-athlete experiences | – | – | – |

| High school experience of online learning | – | + | – |

| Self-directed learning on learning outcomes in MOOCs | + | + | + |

| Students’ self-directed learning in English (foreign language) | + | – | + |

| Guiding teaching strategies | + | + | + |

| Students’ acceptance towards online learning | – | + | – |

| Self-directed learning and attitude on online learning | – | – | – |

| Mental health of high school students | + | + | + |

| School connectedness still matters | – | – | – |

| Implementation and challenges of online education | – | – | – |

| Challenges and opportunities in online distance learning | + | + | – |

| Student evaluations of transitioned-online courses | – | – | – |

| Adaptability and high school students’ online learning | – | + | – |

| The impact of learning on science, social and digital literacy | – | – | – |

| Factors affecting students’ happiness on online learning | + | + | + |

| A comparison of online learning challenges | – | – | – |

| “Teachers act like we’re robots” | – | – | – |

| A literature review on teaching and learning | + | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).