1. Introduction

Breastfeeding has consistently been shown to be an exceptional preventive intervention for both infants and mothers. The "personalized medicine provided by human milk" includes protection against morbidity and mortality, enhanced cognitive development, and a potential decrease in the likelihood of obesity and diabetes among breastfed children compared to those who are not breastfed. Furthermore, breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast cancer for lactating women, improves birth spacing, and potentially decreases the risk of ovarian cancer and diabetes. [

1,

2]

There are few contraindications to breastfeeding. Some health conditions that can simply hinder the initiation and duration of breastfeeding, are mistakenly considered to be real contraindications to the practice. The decision of a mother to breastfeed her infant is often influenced by the perspectives held by healthcare professionals and the extent of knowledge the mother possesses.[

3]

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusively breastfeeding infants for the first six months of their life, followed by the introduction of complementary foods while continuing to breastfeed for at least one year. [

4] Despite the established benefits of breast milk, global breastfeeding rates remain far below international targets, particularly in high-income countries. According to the 2020 Breastfeeding Report Card of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, fewer than 50% of infants in the United States were exclusively breastfed for the first three months. [

5,

6] According to recommendations from WHO, it appears that only mothers in Finland exclusively breastfeed their babies for six consecutive months. [

7]

Despite the mother’s breastfeeding intentions, there is a gap between intentions and feeding practices. There are various factors that influence a mother’s decision to breastfeed, including psychological, economic, and social factors. It is also important to have adequate nursing support during the first few days after delivery. [

8,

9]

While many nurses have received education on breastfeeding, it is not uncommon for women to seek additional information on the subject through online forums. These forums often reveal that inadequate milk supply or difficulty feeding from the breast are frequent reasons for women to discontinue breastfeeding. [

10,

11]

It is important for the nursing staff responsible for postpartum care to receive sufficient training. It is crucial to provide education and training to healthcare professionals on breastfeeding-related knowledge and skills. This has been found to have a positive impact on nurses’ attitudes towards breastfeeding. [

12] Moreover, a positive relationship among mothers and nursing staff is associated with early initiation of breastfeeding, even in preterm infants.[

13]

The provision of information to women regarding breastfeeding is a critical matter that should be addressed at the earliest opportunity, even before childbirth. Mothers often express the sentiment that with more guidance and support from hospital or community staff, as well as their families, they would have been able to breastfeed for a more extended period. Specifically, mothers identify the lack of expert advice and assistance with attachment and latching as a significant factor in the premature termination of breastfeeding. [

14,

15] Studies have shown that healthcare professionals with specific expertise in the area of breastfeeding can play a valuable role as advocates, guiding mothers to begin the process early and reducing the likelihood of abandonment when confronted with initial obstacles. [

16]

It is essential to promote exclusive breastfeeding during postpartum hospitalization to establish a strong foundation for continued exclusive breastfeeding at home. Offering support for breastfeeding immediately after childbirth increases the likelihood of mothers continuing with exclusive breastfeeding. [

16,

17]

Infant feeding is strongly related to socioeconomic determinants of health and far from being an individual decision made by each woman. The varying rates of breastfeeding initiation and continuation in different settings suggest that social and cultural factors, as well as norms, public policy, and the availability of appropriate care and support, greatly impact infant feeding rates. [

18,

19]

Awareness of which are the modifiable determinants affecting breastfeeding is essential in managing and supporting the breastfeeding dyad. [

20,

21] Health-care providers play a crucial role in promoting exclusively breastfeeding. [

22] The aim of this research is to examine the effectiveness of having a nurse present continuously in the Rooming-in Unit, who provides information and attends to mothers’ inquiries by moving from bed to bed, as opposed to having a nurse available on call. The objective is to enhance the rate of exclusive breastfeeding.

2. Materials and Methods

We carried out a prospective cohort study to evaluate exclusive breastfeeding during the first three months of life in mother-child dyads in two Neonatology Units in the same geographical area in Italy although within different settings: Ente Ecclesiastico Ospedale Generale Miulli of Acquaviva delle Fonti with on-site nurses h24 in the Nurse Unit (on site group) and Policlinico of Bari with nurses only available on call h24 from Neonatology Unit (on call group). In on-call group, when a mother needs breastfeeding support, the nurse is called by phone and comes to the mother as soon as possible. The time between the call and the arrival of the nurse can be variable, considering that nurses also take care of the patients admitted to the Neonatology Unit and that the Obstetrics and Neonatology Units are on two different floors.

Both Hospitals follow the steps 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative [

23]. The ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding are as follows:

Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health-care staff.

Train all health-care staff in the skills necessary to implement this policy.

Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within a half-hour of birth.

Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation, even if they are separated from their infant.

Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicate.

Practice rooming-in – allow mothers and infants to remain together – 24 hours a day.

Encourage breastfeeding on demand.

Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants.

Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic.

Both local Ethics Committees approved the study protocol.

All mother-baby dyads admitted to the units from 3 January to 31 of March 2018 were considered for enrollment.

Healthy, at-term newborns with gestational age ≥ 37 weeks in “rooming in” (baby in the same room of the mother all day) from birth to discharge and never hospitalized in Neonatal Intensive or Sub-Intensive Care Unit were included.

Exclusion criteria entailed all maternal and/or neonatal conditions that could interfere with breastfeeding (maternal HIV or active tuberculosis infection, herpes simplex lesions on both breasts, use of therapeutic radioactive isotopes, or exposure to radioactive materials, galactosemia of the infant) or women not speaking Italian for accuracy. Informed consent was obtained from both parents.

Prior to discharge, the mother underwent a structured interview in which she was asked a series of questions from a comprehensive questionnaire. The questionnaire encompassed a variety of topics, including maternal age, educational background, attendance at prenatal classes, previous pregnancies, method of delivery, utilization of pacifiers, nipple fissures, and overall satisfaction with the support provided by nursing staff. Variables subjected to changes during the timeframe of the study were collected by phone interview at 30 and 90 days of the newborn’s life. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the recommended method of feeding for infants involves exclusive consumption of breast milk without the addition of any other liquids or solids. In essence, a breastfed infant is one who only receives sustenance through breast milk. [

24]

During the study period, 400 infants were born at Ente Ecclesiastico Miulli Hospital. However, 43 preterm newborns with a gestational age of less than 37 weeks and 51 newborns who were not exclusively assisted in rooming were excluded from the study. A total of 303 dyads met the eligibility criteria. Among those, 7 were excluded (2 declined to participate and 5 did not speak Italian). At this hospital, the Rooming-in Unit is always staffed by nurses who have extra training as lactation consultants. These nurses are present in the ward at all times (on-site group).

Out of the 425 infants born in Policlinico Hospital, 109 preterm newborns with gestational age < 37 weeks and 48 newborns not assisted in rooming were excluded. A total of 268 dyads met the eligibility criteria. Among those, 3 were excluded because of the lack of Italian fluency. In Policlinico Hospital, a single nurse with additional training as lactation consultant was available on call when a mother needed help for breastfeeding or to answer her questions but was not physically present in the mother’s hospital ward (Rooming in Unit). However, they carried out a minimum of two rounds in the Rooming-in Unit per day. Throughout the day, a family member was present in the same room as the mother and newborn to provide care (on-call group).

So, a total of 564 mother-baby dyads were examined, 299 in the on-site group and 265 in the on-call group.

Data were collected by a healthcare professional at discharge and/or extracted from infants’ computerized medical charts (Neocare, I&T Informatica e Tecnologia Srl, Italy) and by phone interview at 30 and 90 days of newborn’s life. During the 30-day and 90-day interviews, one mother did not respond, and as a result, she was excluded from the analysis for those time periods.

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation or percentage for categorical variables. The Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables. Associations between categorical data were evaluated by using Chi-squared test or Fisher Exact test as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression model was used to adjust for possible confounder factors. For all data a p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 16 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, Texas).

3. Results

Questionnaires showed differences between cohorts (on-site vs. on-call group) in terms of maternal education, prenatal class attendance, pacifier usage, and weight at birth and at discharge. At Policlinico Hospital, the on-call group of mothers had a higher prevalence of primary school education and lower attendance at prenatal classes than the on-site group at Ente Ecclesiastico Miulli Hospital. Furthermore, the on-call group exhibited a higher incidence of pacifier use and a slightly greater average newborn weight. Characteristics of mothers and infants in the two study groups are reported in

Table 1.

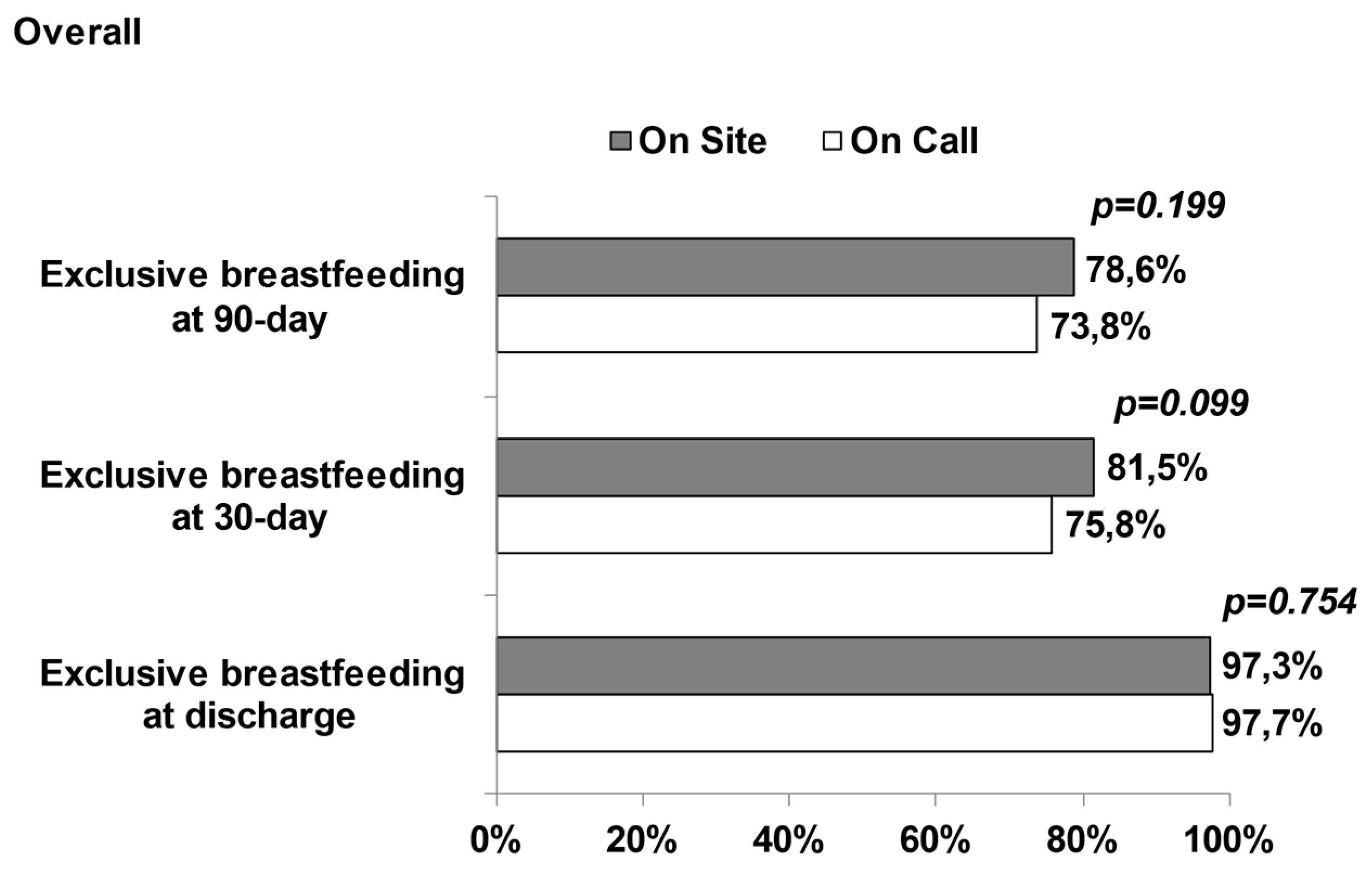

In the two groups, exclusive breastfeeding was observed in 550 dyads at discharge (97.5%), 444 dyads (78.9%) at 30 days and 396 dyads (76.4%) at 90-days. At discharge, there were no differences in the proportion of breastfeeding between the on-site and on-call groups (97.3 % and 97.7%, respectively) . The on-site group had a significantly higher proportion of exclusively breastfed infants compared to the on call group.at 30 days (81.5% vs. 75.8%, respectively) and 90 days (78.6% vs. 73.8%, respectively). Breastfeeding proportion in on site and on call group are reported in

Figure 1.

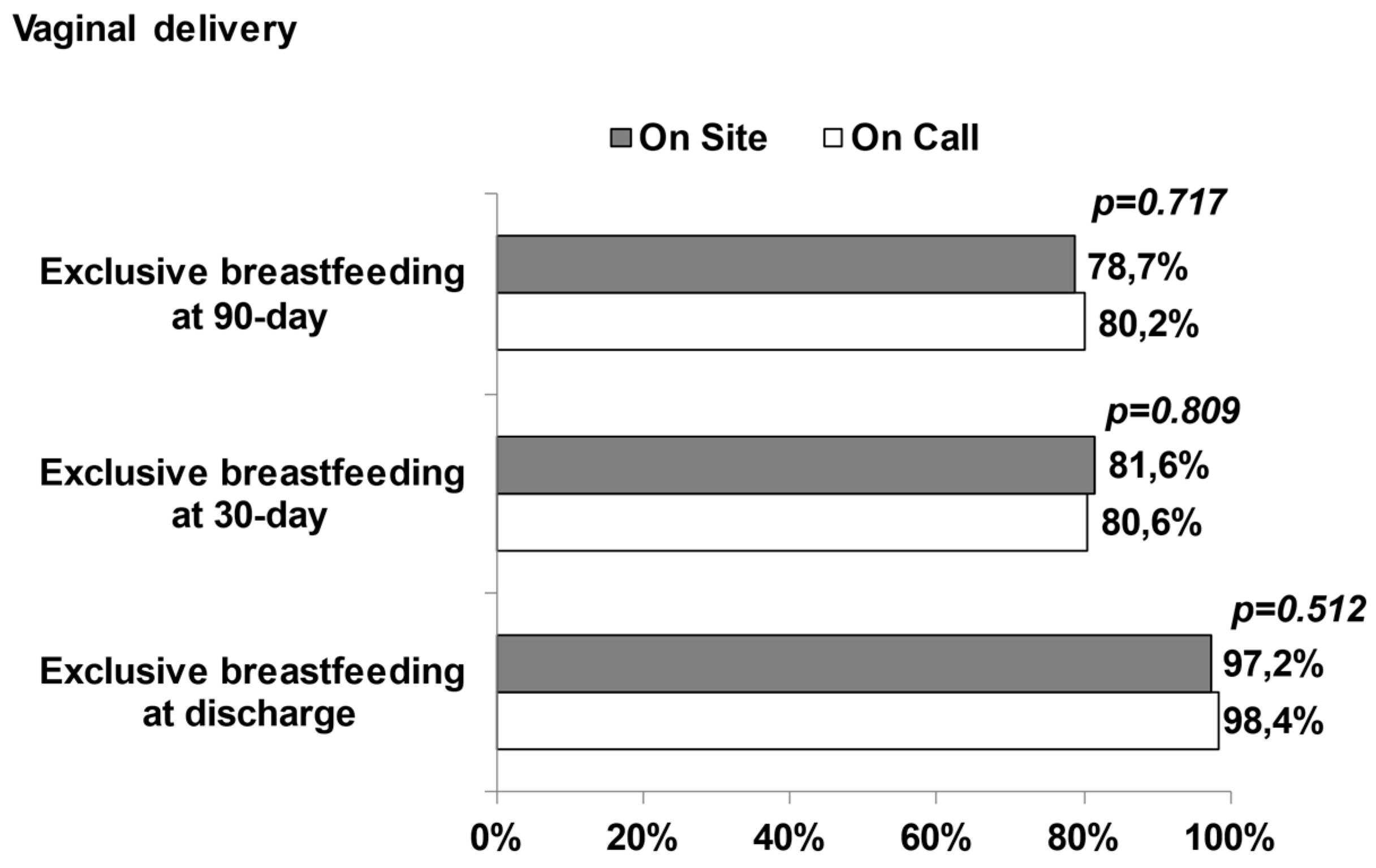

We further categorized the overall population into two subgroups by mode of delivery: vaginal delivery group and cesarean section group.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of mothers and infants in the two study groups stratified for way of delivery.

In the group of mothers who had vaginal deliveries, there were differences between the cohorts in several factors. These included education level, attendance at prenatal classes, use of pacifiers, birth weight, and gestational age. Specifically, the on-call group had a higher percentage of mothers with primary school education, lower attendance at prenatal classes, more frequent use of pacifiers, and slightly higher birth weight compared to the on-site group.

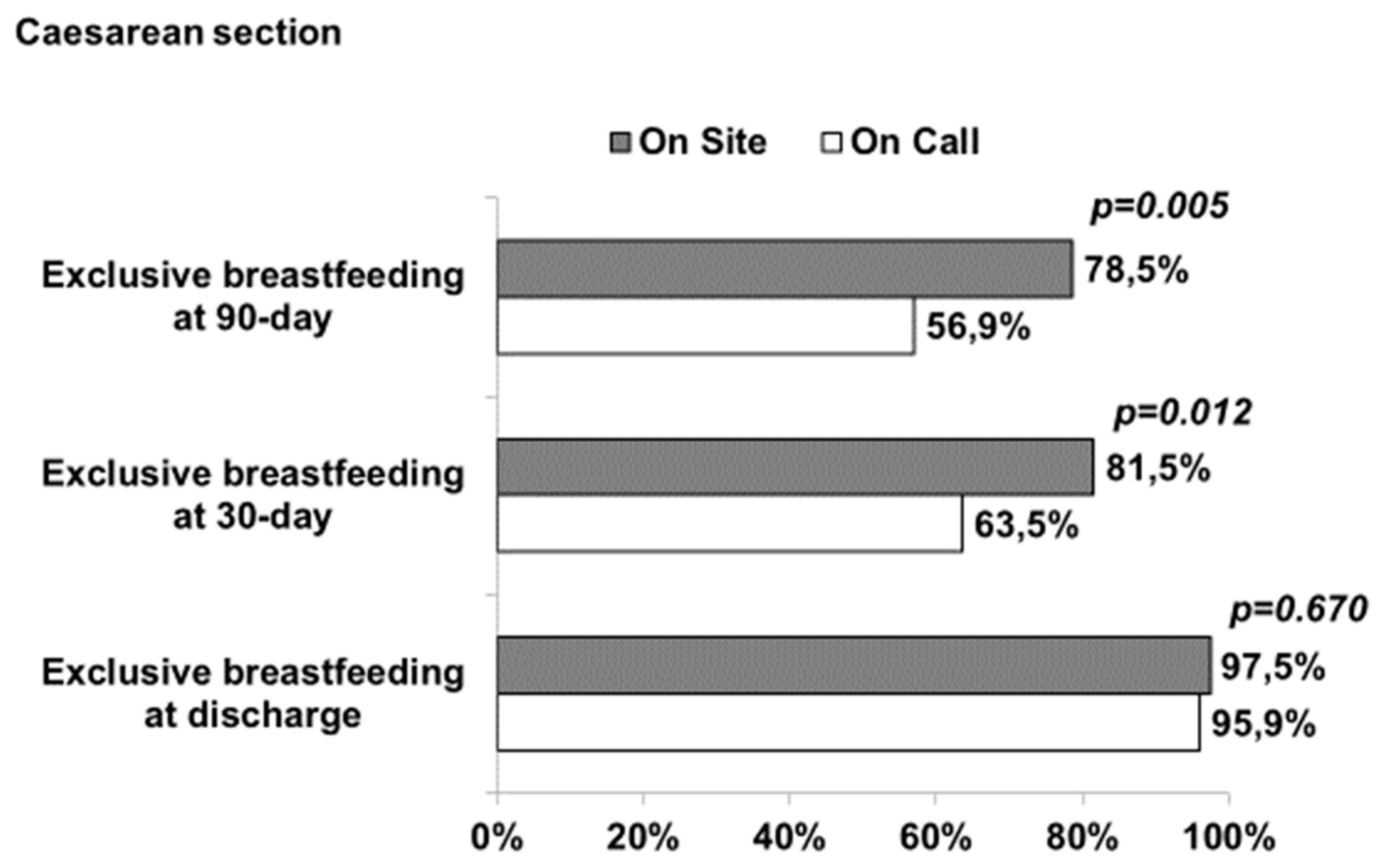

There were notable differences observed among the cohorts within the subgroup that underwent cesarean section in terms of maternal education, attendance in prenatal classes, and satisfaction with the support provided by the nursing staff during postoperative recovery. Specifically, the on-call group exhibited a higher proportion of mothers with primary school education, while a lower likelihood of university education was noted in comparison to the on-site group. Moreover, the on-call group reported lower levels of satisfaction with the nursing support provided during the recovery phase.

No statistical differences were found between on-site and on-call groups in infants born from vaginal delivery. Newborns delivered through cesarean section had higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 30 and 90 days of life in the on-site group compared to the on-call group. However, both groups had similar proportions of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Even after adjusting for education and mother satisfaction with nursing care, there were still statistical differences in the cesarean section group at both 30 and 90 days of the infants’ lives (p<0.05).

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Numerous studies have shown that rooming-in can have a positive impact on breastfeeding rates. According to the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund, rooming-in is a hospital practice where new mothers and their infants stay in the same room for 24 hours a day from the time they arrive in their room after delivery. [

20] In this study, both centers have implemented rooming in, but the only difference is the method of nurse support. Pediatric nurse practitioners rated as slightly important the limited time during health supervision visits to address breastfeeding problems and to give routine advice on breastfeeding. [

21]

The continuous presence of a nurse expert in breastfeeding support independently of on-site or on-call settings should reduce such limitations as our study suggests. The nurse’s role in supporting breastfeeding may differ depending on the time and location of patient care. In each setting, however, the nurse plays a significant role in helping the mother to begin breastfeeding and to enjoy it, while providing her infant with optimum nutrition for his early growth and development. [

17] Postnatal breastfeeding counselling and support have been shown to increase rates of breastfeeding up to 6 months of age. [

22]

We found a high rate of breastfeeding at three months in the population we studied. This confirms the importance of nursing and rooming-in, regardless of the setting of the rooming-in spaces. It is important to learn how to properly position and attach a newborn to the nipple early on to avoid breastfeeding issues later. During the stay at a maternity and newborn facility, it is a good opportunity to discuss and address any concerns or problems related to breastfeeding. This will help build the mother’s confidence in her ability to breastfeed even when not with a nurse.

Cesarean section is a well-known determinant of reduced exclusive breastfeeding rate. [

23] The presence of an on-site nurse seems to increase exclusive breastfeeding, after discharge, at 30 and 90 days of life. The presence of a nurse around the clock in the same ward as the mother can play a crucial role in identifying any potential breastfeeding difficulties in the mother-newborn dyad. This is especially relevant in cases of cesarean section where the interaction between the mother and child can be impeded, further underscoring the importance of having a skilled healthcare provider available at all times to offer assistance and support.

Many interventions have been recommended to promote and increase breastfeeding. [

24,

25]

According to our research, having a nurse on site during the mother-infant rooming-in period can promote exclusive breastfeeding up to three months for mothers who have had a caesarean delivery.

Author Contributions

G.L., D.M. and M.E.B. conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript; M.C. and N.L. made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and interpretation of the data; FM.G. made statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was critically revised and finally approved as submitted by all the authors.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ecclesiastical General Hospital F. Miulli, Acquaviva delle Fonti, Italy, approved the study (No. 6641; January 4, 2021). The Ethics Committee of A.O.U.C. Policlinico of Bari, Italy, received the approval of the Ethics Committee of Acquaviva delle Fonti”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable. NICU consent, signed by parents at hospital admission, allows to use any personal data in anonymous form for scientific reason or publication”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Victora:, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st Century: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Lifelong Effect. The Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, S.; Milanaik, R.; Adesman, A. Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Benefits of Breastfeeding. Curr Opin Pediatr 2016, 28, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davanzo, R. Controversies in Breastfeeding. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartner, L.M.; Morton, J.; Lawrence, R.A.; Naylor, A.J.; O’Hare, D.; Schanler, R.J.; Eidelman, A.I. ; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnode, C.D.; Henninger, M.L.; Senger, C.A.; Perdue, L.A.; Whitlock, E.P. Primary Care Interventions to Support Breastfeeding: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016, 316, 1694–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding Accessible Version:. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htmBreastfeeding Report Card United States, 2020. New York 2020, 6.

- Lebron, C.N.; St. George, S.M.; Eckembrecher, D.G.; Alvarez, L.M. “Am I Doing This Wrong?” Breastfeeding Mothers’ Use of an Online Forum. Matern Child Nutr 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizzari, G.; Morniroli, D.; Consales, A.; Capelli, V.; Crippa, B.L.; Colombo, L.; Sorrentino, G.; Bezze, E.; Sannino, P.; Soldi, V.A.; et al. Knowledge and Attitude of Health Staff towards Breastfeeding in NICU Setting: Are We There yet? An Italian Survey. Eur J Pediatr 2020, 179, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almqvist-Tangen, G.; Bergman, S.; Dahlgren, J.; Roswall, J.; Alm, B. Factors Associated with Discontinuation of Breastfeeding before 1 Month of Age: Factors Associated with Discontinuation of Breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica 2012, 101, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taveras, E.M.; Capra, A.M.; Braveman, P.A.; Jensvold, N.G.; Escobar, G.J.; Lieu, T.A. Clinician Support and Psychosocial Risk Factors Associated With Breastfeeding Discontinuation. PEDIATRICS 2003, 112, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, R.; Marranzano, M.; La Rosa, V.L.; Giorgianni, G.; Commodari, E.; Quattrocchi, R.; Cacciola, S.; Guardabasso, V. Factors Influencing Uptake of Breastfeeding: The Role of Early Promotion in the Maternity Hospital. IJERPH 2021, 18, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakala, M.; Kaakinen, P.; Kääriäinen, M.; Bloigu, R.; Hannula, L.; Elo, S. Maternity Ward Staff Perceptions of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Finnish Maternity Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur J Midwifery 2021, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, A.; Gavine, A.; Renfrew, M.J.; Wade, A.; Buchanan, P.; Taylor, J.L.; Veitch, E.; Rennie, A.M.; Crowther, S.A.; Neiman, S.; et al. Support for Healthy Breastfeeding Mothers with Healthy Term Babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017. [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Burmaz, T.; Arendt, M.; Nilsson, I.; Mikiel-Kostyra, K.; Kondrate, I.; Communal, M.J.; Massart, C.; Chapin, E.; Fallon, M.; et al. Protection, Promotion and Support of Breast-Feeding in Europe: Progress from 2002 to 2007. Public Health Nutr 2010, 13, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, L.; Crippa, B.; Consonni, D.; Bettinelli, M.; Agosti, V.; Mangino, G.; Bezze, E.; Mauri, P.; Zanotta, L.; Roggero, P.; et al. Breastfeeding Determinants in Healthy Term Newborns. Nutrients 2018, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindau, J.F.; Mastroeni, S.; Gaddini, A.; Di Lallo, D.; Fiori Nastro, P.; Nastro, P.F.; Patanè, M.; Girardi, P.; Fortes, C. Determinants of Exclusive Breastfeeding Cessation: Identifying an “at Risk Population” for Special Support. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, K.G. The Role of the Nurse in Support of Breast Feeding. J Adv Nurs 1979, 4, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

World Health Organization; Unicef Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding: The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative for Small, Sick and Preterm Newborns; 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-000564-8.

-

World Health Organization Guideline: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-155008-6.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe The WHO European Health Equity Status Report Initiative: Case Studies; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski, L.; Mimm, N.; Porter, S. Pediatric Nurse Practitioner Barriers to Supporting Breastfeeding by Mothers and Infants. J Perinat Educ 2018, 27, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

World Health Organization Guideline: Counselling of Women to Improve Breastfeeding Practices; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-155046-8.

- Ragusa, R.; Giorgianni, G.; Marranzano, M.; Cacciola, S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Giarratana, A.; Altadonna, V.; Guardabasso, V. Breastfeeding in Hospitals: Factors Influencing Maternal Choice in Italy. IJERPH 2020, 17, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, N.K.; Woods, N.F.; Blackburn, S.T.; Sanders, E.A. Interventions That Enhance Breastfeeding Initiation, Duration, and Exclusivity: A Systematic Review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2016, 41, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, N.K.; Woods, N.F. Outcome Measures in Interventions That Enhance Breastfeeding Initiation, Duration, and Exclusivity: A Systematic Review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2018, 43, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).