Submitted:

25 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Assess the impact of COVID-19 on the provision, utilisation, and availability of health services

- Understand the health system’s response – adaptations, interventions and efforts for continuity and resumption of services

- Evaluate the implications of COVID-19 and its response on individuals – Health care providers and health care seekers

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion criteria

- ▪

- Studies conducted exclusively within the Indian context, from the onset of Covid-19 to its first peak and in its aftermath until December 15th, 2020

- ▪

- Primary studies of any research design

- ▪

- Studies evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on the provision, utilisation, and availability of health services

- ▪

- Studies exploring the health system’s response in terms of adaptations, interventions and efforts made in different types of health facilities for maintaining the continuity of services

- ▪

- Studies examining the impact of the pandemic on individuals – health care providers, individuals with acute and chronic diseases

2.2. Exclusion criteria

- ▪

- Studies on pandemics other than COVID-19

- ▪

- Studies that are not primary (like reviews, reports, policy briefs, commentary etc.)

- ▪

- Global/multi-country studies with India just as one of the settings and studies not conducted in the Indian context.

- ▪

- Studies evaluating aetiology, pathophysiology, histopathology, serology or laboratory examination of COVID-19, clinical trials, or vaccine development.

- ▪

- Studies that are not written in English

2.3. Search strategy

2.4. Data extraction (selection and coding)

2.5. Data items

2.6. Outcomes

2.6.1. Primary

-

Health services for varied health conditions:

- ▪

-

Changes in the provision, utilisation, or availability of:

- ○

- Outpatient department (OPD)

- ○

- Elective health services

- ○

- Emergency health services

- 2.

-

Health system response to COVID-19:

- ▪

-

Efforts and adaptations made in:

- ○

- General precautionary and infection prevention measures

- ○

- Protocols and guidelines

- ○

- Staff allocation, management, and training

- ○

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- ○

- Physical infrastructure and resources.

2.6.2. Secondary

-

Mental/psychological health of health care providers:

- ▪

- Depression, anxiety, and burnout

- ▪

- Fear of infecting themselves and transmitting it to family members,

- ▪

- Financial repercussions

- General health or disease conditions of health care seekers/individuals

2.7. Critical appraisal – quality assessment

2.8. Data analysis

3. Results

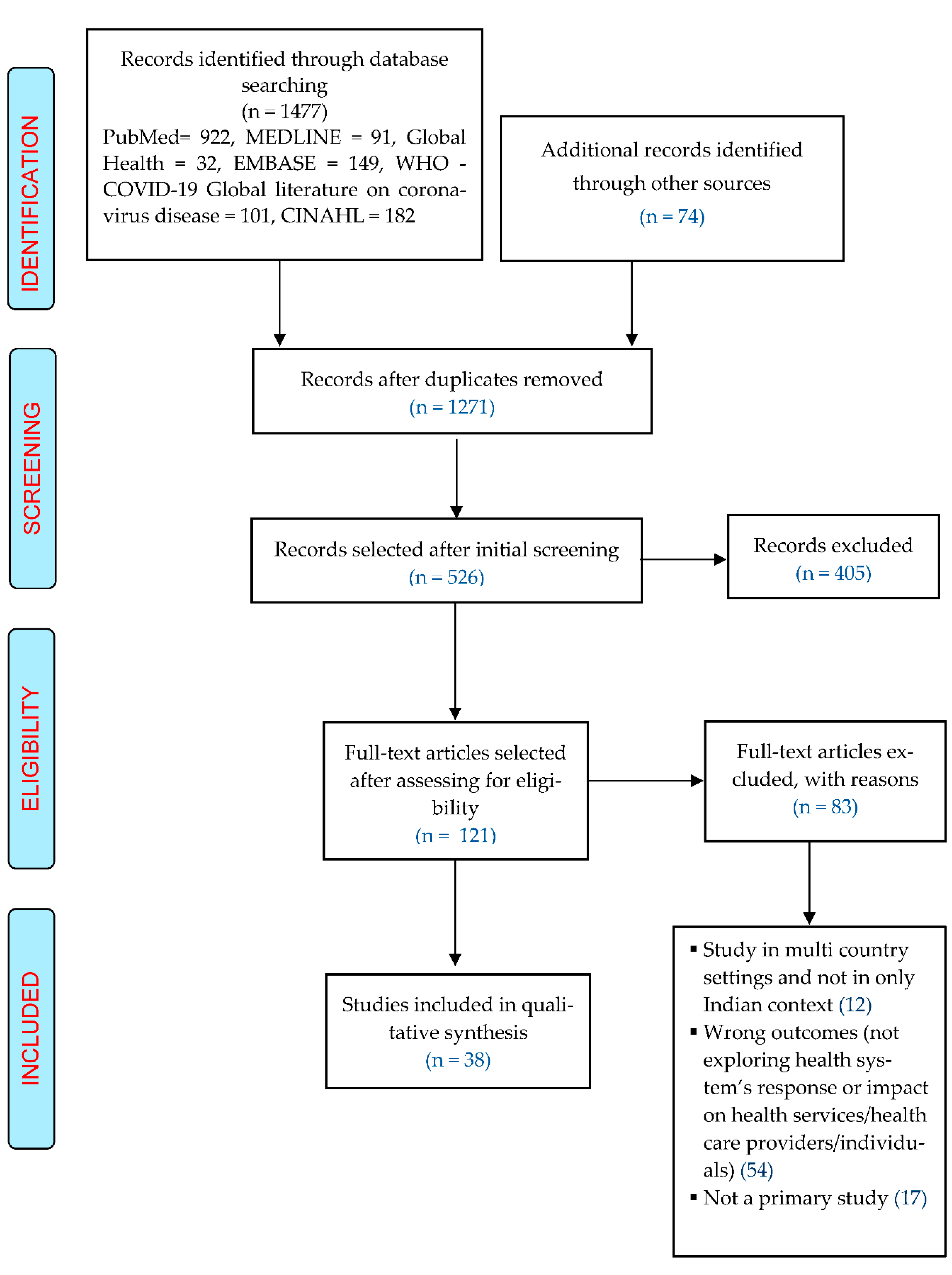

3.1. Screening and inclusion of studies

3.2. Narrative analysis

3.2.1. Impact of COVID 19 and turn of events on provision, availability, and utilisation of health services

- a)

- Outpatient department (OPD) services

- b)

- Elective services

- c)

- Emergency services

3.2.2. Health system’s response – adaptations and efforts for resumption of health care services

- a)

- General precautionary and infection prevention measures

- b)

- Protocol and guidelines

- c)

- Staff allocation, management, and training

- d)

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- e)

- Preoperative/OT/post-operative measures

- f)

- Physical infrastructure and resources

3.2.3. Impact of pandemic on healthcare providers and individuals/communities

- a)

- Impact on health care providers

- ▪

- Depression, stress, anxiety, and burnout in health care providers

- ▪

- Fear of contracting infection and carrying it at home

- ▪

- Stigmatisation

- ▪

- Financial impact

- b)

- Effect of pandemic on healthcare seekers

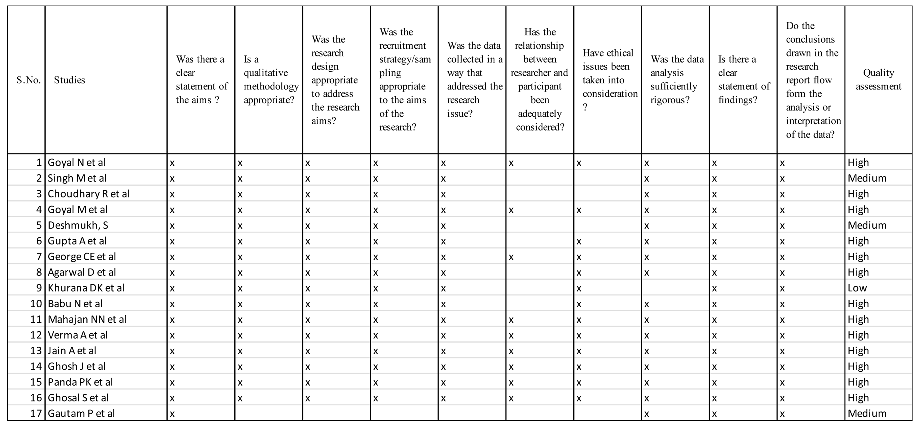

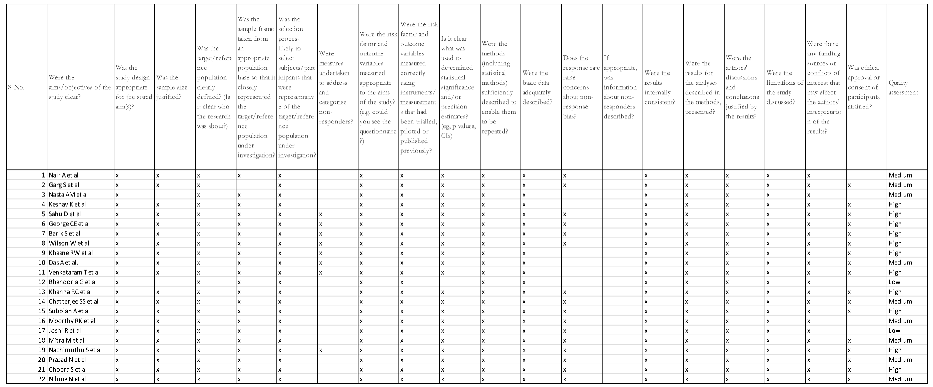

3.3. Quality appraisal of included studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Quality appraisal of observational studies using adapted CASP checklist

Appendix A.2. Quality appraisal of cross-sectional surveys using adapted JBI tool

References

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, N.; Venkataram, T.; Singh, V.; Chaturvedi, J. Collateral Damage Caused by COVID-19: Change in Volume and Spectrum of Neurosurgery Patients. J Clin Neurosci 2020, 80, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, P.; Gandhi, V.; Naik, S.; Mane, A.; Kanitkar, G.; Hegde, S.; Deshmukh, S. Cancer Care in a Western Indian Tertiary Centre during the Pandemic: Surgeon’s Perspective. J Surg Oncol 2020, 122, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.G.; Gandhi, R.A.; Natarajan, S. Effect of COVID-19 Related Lockdown on Ophthalmic Practice and Patient Care in India: Results of a Survey. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020, 68, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Sanghavi, P.; Patel, B.; Umrania, R.; Chishi, K.; Ghoghari, M. Experience of Palliative Care Services at Tertiary Comprehensive Cancer Centre during COVID-19 Lockdown Phase: An Analytical Original Study. Indian J Palliat Care 2020, 26, S27–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, S.; Basu, S.; Rustagi, R.; Borle, A. Primary Health Care Facility Preparedness for Outpatient Service Provision During the COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020, 6, e19927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasta, A.M.; Goel, R.; Kanagavel, M.; Easwaramoorthy, S. Impact of COVID-19 on General Surgical Practice in India. Indian J Surg 2020, 82, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, P.; Singh, K.; Shekhar, S.; Agrawal, N.; Misra, S. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Maternal Health Due to Delay in Seeking Health Care: Experience from a Tertiary Centre. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021, 152, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.; Naik, S.; Zade, B.; Patwa, R.; Gawande, J.; Watgaonkar, R.; Wagh, S.; Deshmukh, S.; Gautam, P.; Gandhi, V.; et al. Impact of the Pandemic on Cancer Care: Lessons Learnt from a Rural Cancer Centre in the First 3 Months. J Surg Oncol 2020, 122, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Arora, V.; Nair, D.; Agrawal, N.; Su, Y.-X.; Holsinger, F.C.; Chan, J.Y.K. Status and Strategies for the Management of Head and Neck Cancer during COVID-19 Pandemic: Indian Scenario. Head Neck 2020, 42, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.; Agrawal, T.; Rathod, V.; Bagaria, V. Impact of COVID 19 Lockdown on Orthopaedic Surgeons in India: A Survey. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020, 11, S283–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barik, S.; Paul, S.; Kandwal, P. Insight into the Changing Patterns in Clinical and Academic Activities of the Orthopedic Residents during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020, 28, 3087–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, D.K.; Raheja, S.G.; Dayal, M.; Pande, D.; Ganapathy, U. COVID 19: The New Normal in the Clinic: Overcoming Challenges in Palliative Care. Indian J Palliat Care 2020, 26, S81–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataram, T.; Goyal, N.; Dash, C.; Chandra, P.P.; Chaturvedi, J.; Raheja, A.; Singla, R.; Sardhara, J.; Singh, B.; Gupta, R. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Neurosurgical Practice in India: Results of an Anonymized National Survey. Neurol India 2020, 68, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N.; Kohli, P.; Mishra, C.; Sen, S.; Arthur, D.; Chhablani, D.; Baliga, G.; Ramasamy, K. To Evaluate the Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic and National Lockdown on Patient Care at a Tertiary-Care Ophthalmology Institute. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020, 68, 1540–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, N.N.; Pednekar, R.; Patil, S.R.; Subramanyam, A.A.; Rathi, S.; Malik, S.; Mohite, S.C.; Shinde, G.; Joshi, M.; Kumbhar, P.; et al. Preparedness, Administrative Challenges for Establishing Obstetric Services, and Experience of Delivering over 400 Women at a Tertiary Care COVID-19 Hospital in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020, 151, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Rajput, R.; Verma, S.; Balania, V.K.B.; Jangra, B. Impact of Lockdown in COVID 19 on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020, 14, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Atal, S.; Fatima, Z.; Balakrishnan, S.; Sharma, S.; Joshi, A. Diabetes Care during COVID-19 Lockdown at a Tertiary Care Centre in India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020, 166, 108316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Basu, M. A Study on Challenges to Health Care Delivery Faced by Cancer Patients in India During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720942705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, N.; Bhatt, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Kohli, H.S.; Gopalakrishnan, N.; Fernando, E.; Sahay, M.; Rajapurkar, M.; Chowdhary, A.R.; Rathi, M.; et al. The Adverse Effect of COVID Pandemic on the Care of Patients With Kidney Diseases in India. Kidney Int Rep 2020, 5, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, R.K.; Rajshekhar, V. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Neurosurgical Practice in India: A Survey on Personal Protective Equipment Usage, Testing, and Perceptions on Disease Transmission. Neurol India 2020, 68, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahul Choudhary; Dinesh Gautam; Rohit Mathur; Dinesh Choudhary Management of Cardiovascular Emergencies during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg Med J 2020, 37, 778. [CrossRef]

- Keshav, K.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, P.; Baghel, A.; Mishra, P.; Huda, N. How Much Has COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Indian Orthopaedic Practice? Results of an Online Survey. Indian J Orthop 2020, 54, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, D.; Chawla, R.; Varshney, T.; Shaikh, N.; Chandra, P.; Kumar, A. Managing Vitreoretinal Surgeries during COVID-19 Lockdown in India: Experiences and Future Implications. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 2020, 68, 2126–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandoria, G.; Shylasree, T.S.; Bhandarkar, P.; Ahuja, V.; Maheshwari, A.; Sekhon, R.; Somashekhar, S.P. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Gynecological Oncology Care: Glimpse into Association of Gynecological Oncologists of India (AGOI) Perspective. Indian J Gynecol Oncol 2020, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbian, A.; Kaur, S.; Patel, V.; Rajanbabu, A. COVID-19 and Its Impact on Gynaecologic Oncology Practice in India-Results of a Nationwide Survey. Ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, P.K.; Dawman, L.; Panda, P.; Sharawat, I.K. Feasibility and Effectiveness of Teleconsultation in Children with Epilepsy amidst the Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic in a Resource-Limited Country. Seizure 2020, 81, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Goyal, V.; Varma, C. Reflection of Epidemiological Impact on Burden of Injury in Tertiary Care Centre, Pre-COVID and COVID Era: “Lockdown, a Good Fortune for Saving Life and Limb”. Indian J Surg 2021, 83, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Gupta, S.; Das, S.; Banerjee, B.B. Attitude, Practice, Behavior, and Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Doctors. Indian J Psychiatry 2020, 62, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.E.; Inbaraj, L.R.; Rajukutty, S.; de Witte, L.P. Challenges, Experience and Coping of Health Professionals in Delivering Healthcare in an Urban Slum in India during the First 40 Days of COVID-19 Crisis: A Mixed Method Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasne, R.W.; Dhakulkar, B.S.; Mahajan, H.C.; Kulkarni, A.P. Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Results of a Questionnaire-Based Survey. Indian J Crit Care Med 2020, 24, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, W.; Raj, J.P.; Rao, S.; Ghiya, M.; Nedungalaparambil, N.M.; Mundra, H.; Mathew, R. Prevalence and Predictors of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among Healthcare Workers Managing COVID-19 Pandemic in India: A Nationwide Observational Study. Indian J Psychol Med 2020, 42, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, J.; Ganguly, S.; Mondal, D.; Pandey, P.; Dabkara, D.; Biswas, B. Perspective of Oncology Patients During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Observational Study From India. JCO Glob Oncol 2020, 6, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Sil, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Rajeev, R.; Thole, A.; Jafferany, M.; Ali, S.N. A Study to Evaluate Depression and Perceived Stress Among Frontline Indian Doctors Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2020, 22, 20m02716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, R.C.; Honavar, S.G.; Metla, A.L.; Bhattacharya, A.; Maulik, P.K. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Ophthalmologists-in-Training and Practising Ophthalmologists in India. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020, 68, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachimuthu, S.; Vijayalakshmi, R.; Sudha, M.; Viswanathan, V. Coping with Diabetes during the COVID - 19 Lockdown in India: Results of an Online Pilot Survey. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020, 14, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; Arora, B.; Dutta, K.; Ghosh, A.; Sinha, B.; Misra, A. Increase in the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes during Lockdown for the COVID19 Pandemic in India: A Cohort Analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020, 14, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilima, N.; Kaushik, S.; Tiwary, B.; Pandey, P.K. Psycho-Social Factors Associated with the Nationwide Lockdown in India during COVID- 19 Pandemic. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2021, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Ranjan, P.; Singh, V.; Kumar, S.; Arora, M.; Hasan, M.S.; Kasiraj, R.; Suryansh; Kaur, D. ; Vikram, N.K.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Lifestyle-Related Behaviours- a Cross-Sectional Audit of Responses from Nine Hundred and Ninety-Five Participants from India. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020, 14, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. COVID-19 Significantly Impacts Health Services for Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-06-2020-covid-19-significantly-impacts-health-services-for-noncommunicable-diseases.

- Ray Moynihan; Sharon Sanders; Zoe A Michaleff; Anna Mae Scott; Justin Clark; Emma J To; Mark Jones; Eliza Kitchener; Melissa Fox; Minna Johansson; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Utilisation of Healthcare Services: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmeyer, J.D.; Barnato, A.; Birkmeyer, N.; Bessler, R.; Skinner, J. The Impact Of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Hospital Admissions In The United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020, 39, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, C.; McDonnell, T.; Barrett, M.; Cummins, F.; Deasy, C.; Hensey, C.; McAuliffe, E.; Nicholson, E. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child Health and the Provision of Care in Paediatric Emergency Departments: A Qualitative Study of Frontline Emergency Care Staff. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, R.; Schmit, N.; Christen, P.; D’Aeth, J.C.; Løchen, A.; Rizmie, D.; Nayagam, S.; Miraldo, M.; Aylin, P.; Bottle, A.; et al. Adapting Hospital Capacity to Meet Changing Demands during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Medicine 2020, 18, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, A.; O’Leary, K.J.; Greysen, S.R.; Harrison, J.D.; Kripalani, S.; Ruhnke, G.W.; Vasilevskis, E.E.; Maselli, J.; Fang, M.C.; Herzig, S.J.; et al. Hospital Ward Adaptation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of Academic Medical Centres. J Hosp Med 2020, 15, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, B.E.; Grabowski, D.C.; Barnett, M.L. Severe Staffing And Personal Protective Equipment Shortages Faced By Nursing Homes During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020, 39, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Graham, M.S.; Joshi, A.D.; Guo, C.-G.; Ma, W.; Mehta, R.S.; Warner, E.T.; Sikavi, D.R.; Lo, C.-H.; et al. Risk of COVID-19 among Front-Line Health-Care Workers and the General Community: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e475–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Maguire, S.; Marks, E.; Doyle, M.; Sheehy, C. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers at Acute Hospital Settings in the South-East of Ireland: An Observational Cohort Multicentre Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Meneses-Echavez, J.F.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Fraile-Navarro, D.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Castro, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Zamanillo Campos, R.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C. Impact of Viral Epidemic Outbreaks on Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord 2020, 277, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S. COVID-19 Exacerbates Violence against Health Workers. The Lancet 2020, 396, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.no. | Author | Area of work | Participants | No. of Participants | Setting/context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gautam P et al | Cancer care | Onco-surgeons | 15 | A tertiary care centre, Pune | |

| Goyal N et al | Neurosurgery | Patients operated under the Department of Neurosurgery since the onset of pandemic | 164 | The Department of Neurosurgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Uttarakhand institute | |

| Nair A et al | Ophthalmic practice | Ophthalmologists | 1260 | Online survey of ophthalmologists from Private clinics, ophthalmic institutes, corporate/multi-specialty hospitals, government/municipal hospitals, freelancing surgeons | |

| Singh M et al | Palliative Cancer care | Patients availing palliative care service | 1161 | Department of pain and palliative medicine in a tertiary comprehensive Cancer centre, Gujarat. | |

| Garg S et al | Primary health care | Supervisors and managers of primary health care facilities | 51 | Primary health care facilities attached to medical colleges and institutions anywhere in India, either in the government or private setting. | |

| Nasta AM et al | General Surgical practice | Surgeons (members of Indian Association of Gastro-intestinal Endo-surgeons -IAGES) | 153 | Online survey of members of Indian Association of Gastro-intestinal Endo-surgeons (IAGES) | |

| Choudhary R et al | Cardiovascular emergencies | Patients presenting with cardiovascular emergencies | 289 | Four tertiary regional emergency departments in western India | |

| Goyal M et al | Maternal health | Pregnant women | 633 | Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur | |

| Deshmukh, S | Cancer | Cancer patients who underwent surgery, CT, and RT | 553 | A charitable cancer hospital, Pune | |

| Keshav K et al | Orthopaedic Practice | Practicing orthopaedic surgeons | 533 | Online nationwide survey | |

| Gupta A et al | Head and neck cancer | Head and neck health care stakeholders | 16 | Major head and neck health care facilities across India | |

| Sahu D et al | Orthopaedic surgery | Orthopaedic surgeons | 611 | Online nationwide survey | |

| George CE et al | Healthcare services in a large slum | A healthcare team of doctors, nurses, paramedical and support staff. | 87 | Community Health Division, Bangalore Baptist Hospital, Bangalore | |

| Agarwal D et al | Ophthalmology | Patients of vitreoretinal surgery | 86 | A government tertiary eye care hospital | |

| Barik S et al | Orthopaedic | Orthopaedic residents | 158 | Seven tertiary care centres in North India | |

| Khurana DK et al | Patient volume, infection prevention measures | All patients coming to the clinic and inpatient referrals. | 108 | Pain and palliative care unit at a tertiary care hospital | |

| Wilson W et al | Stress, depression, anxiety | HCPs (doctors & nurses) directly involved in the triage, screening, diagnosing, and treatment of COVID-19 patients and suspects. | 433 | Online survey - Ten states and one union territory | |

| Khasne RW et al | Burnout/stress | All HCPs (doctors, nurses, paramedics) looking after COVID-19 patients. | 2026 | Nationwide online survey | |

| Das A et al. | Burnout, stress, workload | Frontline doctors involved in clinical services in OPDs, designated COVID-19 wards, screening blocks, fever clinics, and intensive care units | 422 | Tertiary care hospitals in India | |

| Venkataram T et al | PPE, preoperative testing, burnout | Practising neurosurgeons | 201 | Online nationwide survey | |

| Bhandoria G et al | Guidelines, service, teleconsultation | Gynaecological oncologists | 567 | The Association of Gynaecological Oncologists of India (AGOI). | |

| Babu N et al | Procedures, precautions | Patients presenting to the hospital during COVID-19 lockdown | 3434 | Tertiary care dedicated ophthalmic hospital in Tamil Nadu | |

| Khanna RC et al | Stress and fear | Ophthalmologists and ophthalmology trainees | 2355 | Online nationwide survey | |

| Chatterjee SS et al | Stress and anxiety | Doctors | 152 | Online survey - West Bengal | |

| Subbian A et al | Patient volumes, surgical load, and changes in practice protocols | Healthcare professionals involved in the care of gynaecologic cancer patients | 153 | National online survey | |

| Mahajan NN et al | Protocols,measures, preparedness | Obstetric patients | 600 | Multispecialty tertiary care centre in Mumbai | |

| Moorthy RK et al | PPE use, precautions, change in practices | Neurosurgeons | 244 | Online survey of members of the Neurological Society of India | |

| Verma A et al | Patients health, clinical,behavioural risk factors | Patients with T1DM | 52 | Tertiary care teaching hospital |

|

| Joshi R et al | Patients health, clinical, behavioural risk factors | Individuals with diabetes who needed the follow up consultation | 103 | Telemedicine facility of All India Institute of Medical Sciences Bhopal | |

| Jain A et al | Patients/injuries | Trauma victims presented to trauma centre. | 299 | A tertiary care hospital with level 1 trauma centre and a multidisciplinary 600-bed public hospital in Delhi NCR | |

| Mitra M et al | Patient challenges | Cancer patients in different stages of treatment and follow-up | 100 | A 600-bed multispecialty hospital | |

| Ghosh J et al | Patients’ concerns | All patients age ≥ 18 years who are actively undergoing systemic therapy for solid malignancies |

302 | Department of Medical Oncology | |

| Panda PK et al | Telemedicine/young patients | Caregivers of children suffering from neurological disorders | 153 | Pediatric Neurology Division, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh | |

| Nachimuthu S et al | Adherence to medicine, diet, physical activity | Diabetic patients | 100 | A diabetes speciality hospital in Chennai | |

| Prasad N et al | Patient volume and services/procedures | Director or the heads of the departments | 2517 | 26 public sector tertiary care teaching institutes and private sector corporate hospitals | |

| 36. | Ghosal S et al | Individual health/patient concerns | Non-diabetic household members of T2D patients | 100 | Tertiary care diabetes centre |

| 37. | Chopra S et al | Lifestyle related behaviours | Adults age ≥ 18 years | 995 | Nationwide online survey |

| 38. | Nilima N et al | Community/individual health | People from all the states | 1316 | Nationwide online survey |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).