Submitted:

25 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

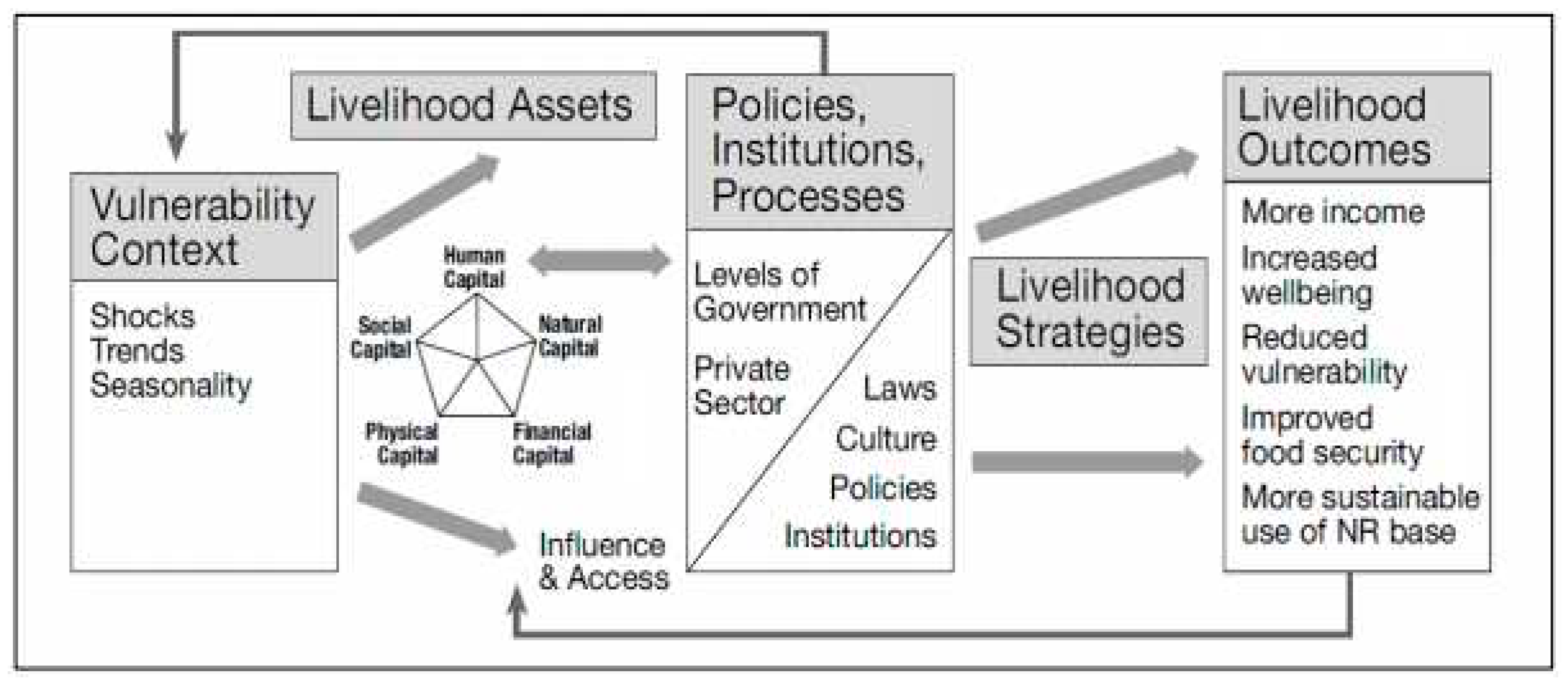

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area

2.2. Sampling procedure

2.3. Data collection methods

2.4. Data analysis tools

2.4.1. Econometric estimation of the impact and the factors that influence the impact of the Fortune 40 program towards rural livelihoods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Challenges experienced in the Fortune 40 program

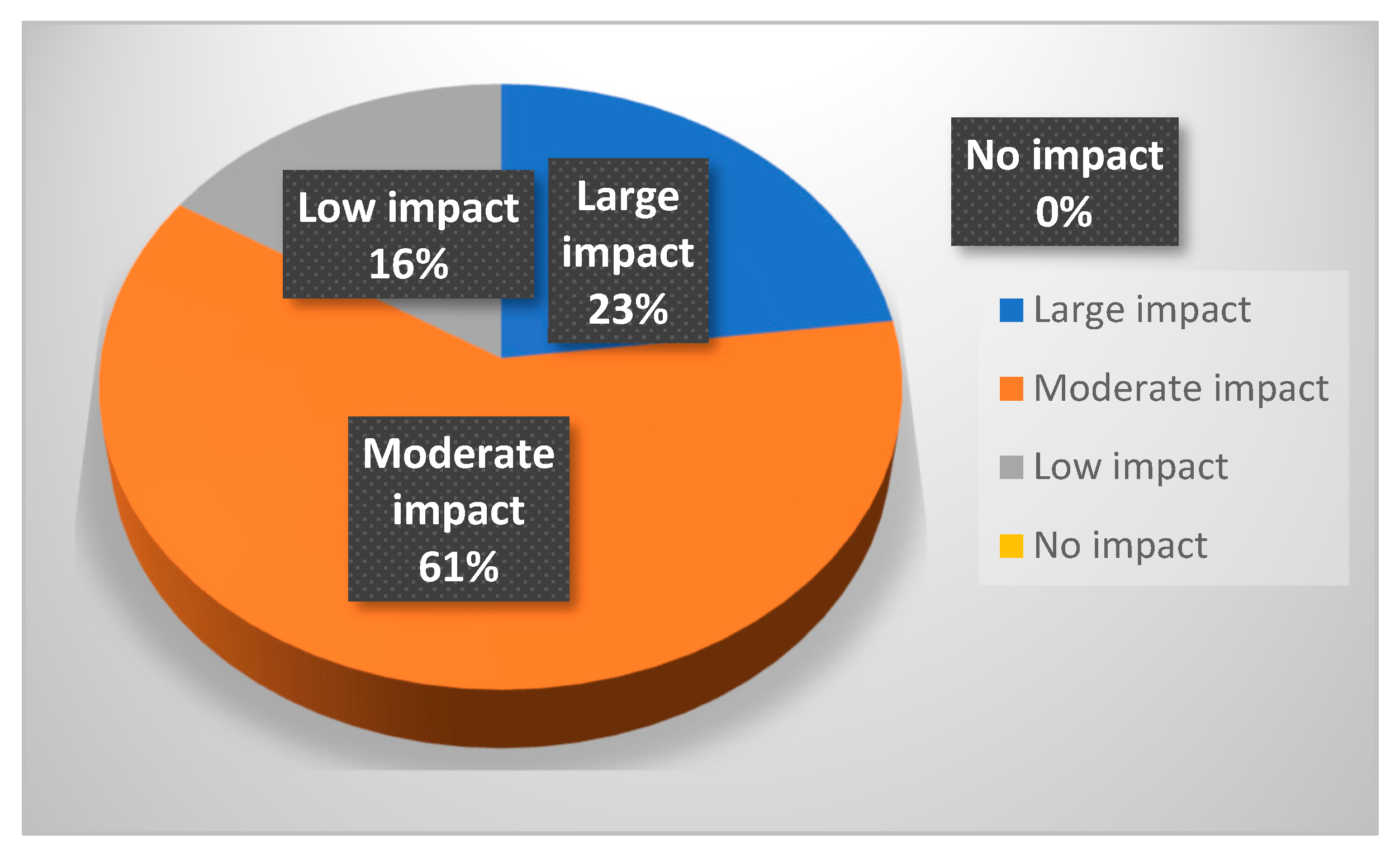

3.2. The impact of Fortune 40 program and the factors that influence the impact of Fortune 40 program towards rural livelihoods

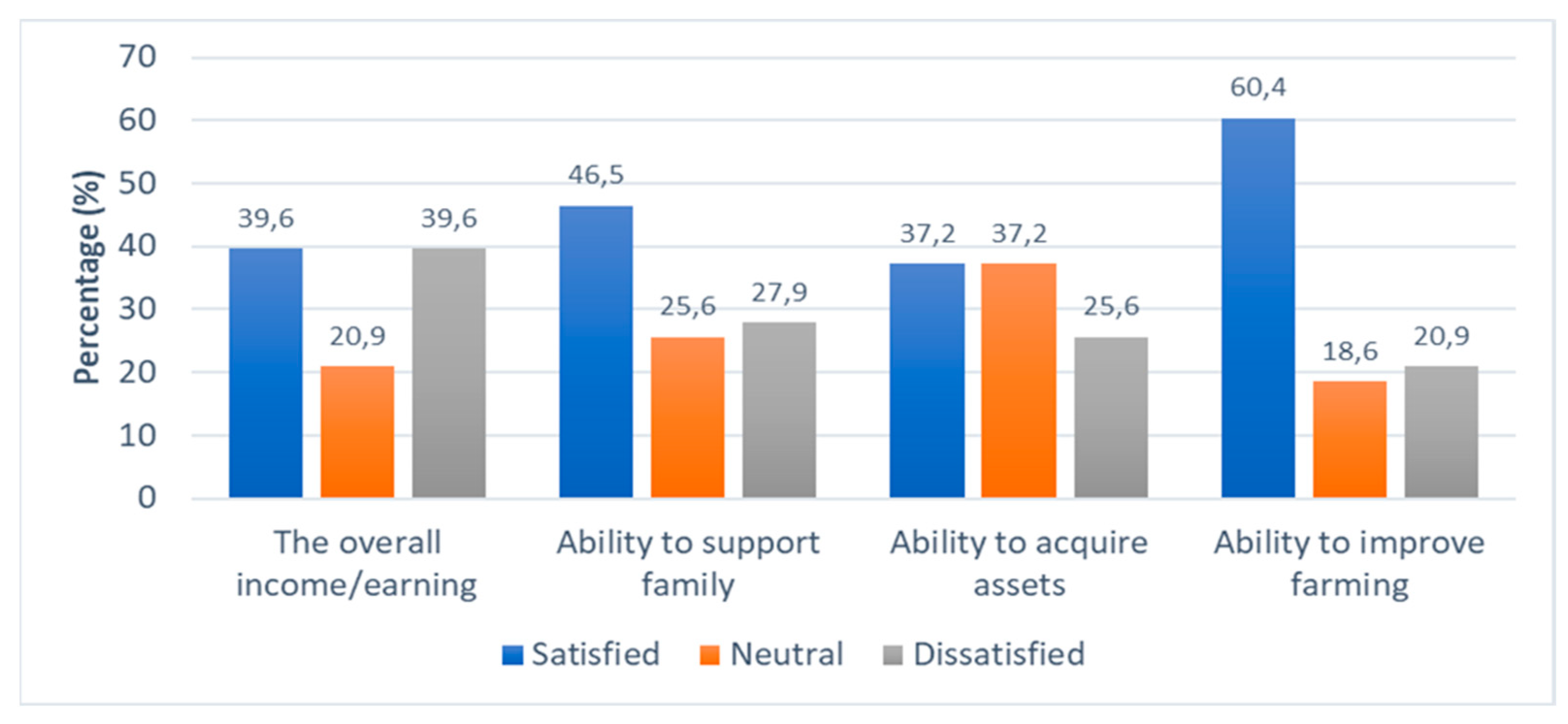

3.2.1. Changes in socio-economic wellbeing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gassner, A.; Harris, D.; MauschK. ; Terheggen, A.; Lopes, C.; Finlayson, R.F.; Dobie, P. Poverty eradication and food security through agriculture in Africa: Rethinking objectives and entry points. Outlook on Agriculture 2019, 48, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stats South Africa. Youth still find it difficult to secure jobs in South Africa. ), 2021. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14415 (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Cloete, A. Youth unemployment in South Africa-a theological reflection through the lens of human dignity. S. Afr. J. of Mis. St. 2015, 43, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K.M. Transitions and Equity. Improving Access, Equity and Transitions in Education: Creating a Research Agenda (No. 1), 2007.

- Dercon, S.; Gollin, D. Agriculture in African development: theories and strategies. Ann. Rev. of Res. Eco. 2014, 6, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Youth Foundation. Promoting agricultural entrepreneurship among rural youth, ), 2014. Available online: https://iyfglobal.org/sites/default/files/library/GPYE_RuralEntrepreneurship.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Baiphethi, M.N.; Jacobs, P. The contribution of subsistence farming to food security in South Africa. Agrek. 2009, 48, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Youth and agriculture: key challenges and concrete solutions. ), 2014. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i394e7E.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Hancel, R.B. Livelihood impacts of the Farm Work Program on households in Bois Content. Thesis. University of the West Indies Campus; .: University of the West Indies Campus, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bushbuckridge Local Municipality. Final integrated development plan, 2018. Available online: http://mfma.treasury.gov.za/Documents/01.%20Intergrated%Development%20Plans/2018-2019/02.%20Local%20municipalities/MP325%20Bushbuckridge/FINAL%IDP%20BLM%202018-19.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Ahmed, F.; Siwar, C.; Idris, N.A.H. The sustainable livelihood approach: reduce poverty and vulnerability. J. of App. Sci. Res. 2011, 7, 810–813. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C.; McDonald, J.; Quist, K. A generalized ordered probit model. Com. in Stats. -Theo. and Meths. 2019, 49, 1712–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedefaw, A.; Sisay, D. Determinants of recommended agronomic practices adoption among wheat producing smallholder farmers in Sekela District of West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. J. of Dev. and Agric. Eco. 2020, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, D.; Mburu, J.; Mignouna, D. Youth agricultural entrepreneurship: assessing the impact of agricultural training programs on performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1697–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnadi, F.; Akwiwu, C. Determinants of youths’ participation in rural agriculture in Imo State, Nigeria. J. of App. Sci. 2008, 8, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanbgu, R.R. Effect of Masibuyele Emasimini agricultural program on food security at new forest irrigation scheme in Bushbuckridge municipality of Ehlanzeni district in Mpumalanga Province. Master’s Diss., University of Limpopo, Polokwane, 2015.

- Zulfiqar, F.; Hussain, A. Forecasting wheat production gaps to assess the state of future food security in Pakistan. J. of F. and Nutri. Dis. 2014, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Thapa, G.B. Fungibility of smallholder agricultural credit: empirical evidence from Pakistan. The Europ. J. of Dev. Res. 2016, 28, 826–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Xiao, Y. Impact of farmers livelihood capital differences on their livelihood strategies in three Gorged Reservoir Area. J. of Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deogharia, P.C. Diversification of agriculture: a review. J. of Eco. and Soc. Dev. 2018, 15, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Prasad, B. Farm types and their characterization in complex agro-ecosystems for informed extension intervention: study from coastal West Bengal, India. Agric. and F. Eco. 2014, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berre, D.; Corbeels, M.; Rusinamhodzi, L.; Mutenje, M. Thinking beyond agronomic yield gap: smallholder farm efficiency under contrasted livelihood strategies in Malawi. Fiel. Cr. Res. 2017, 214, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description | Units of measure |

|---|---|---|

| Impact on rural livelihoods (Y) (OPM Model) | 1=No impact, 2=Low impact, 3=Moderate impact, 4= Large impact | Ordinal |

| Gender of the beneficiary | Male=0, Female=1 | Dummy |

| Age of the beneficiary | Actual years | Years |

| Education level | 0= no formal education, 1= primary education, 2=secondary education, 3= tertiary education | Categorical |

| Years participating in the programme | Actual years | Years |

| Land size | Actual size | Hectares |

| Access to inputs | 1=yes, 0=no | Dummy |

| Market Access | 1=yes, 0= otherwise | Dummy |

| Credit access | 1=yes, 0= otherwise | Dummy |

| Assets acquired by beneficiaries | 0=human capital, 1=natural capital, 2= social capital, 3=financial capital, 4=physical capital | Categorical |

| On-farm Training | 1=yes, 0= otherwise | Dummy |

| Workshops attended | 1= Attended, 0= not attended | Dummy |

| Household size | Number of people in the household | The actual number of household members |

| Farm Income | Monthly income | South African Rands (ZAR) |

| Beneficiaries Income with the exclusion of farm income. | Monthly income | South African Rands (ZAR) |

| Government funds | 1=yes, 0= otherwise | Dummy |

| Variables | B Coefficient | Standard Error | T-statistics | Sig. (P-V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -4.069 | 10.329 | 0.155 | 0.694 |

| Age | 13.067 | 6.8730 | 3.615 | 0.057*** |

| Gender | 0.430 | 1.415 | 0.092 | 0.761 |

| Level of Education | -0.167 | 1.389 | 0.014 | 0.904 |

| Household size | 29.627 | 4.283 | 47.861 | 0.000* |

| Credit Access | -5.587 | 2.699 | 4.285 | 0.038** |

| Government funds | -1.171 | 1.978 | 0.351 | 0.554 |

| Type of Farming | 17.880 | 7.969 | 5.034 | 0.025** |

| Monthly income | 0.002 | 0.001 | 5.034 | 0.025** |

| Workshops attended | -0.623 | 1.947 | 0.102 | 0.749 |

| Land size | 16.758 | 2.997 | 31.264 | 0.000* |

| Model Summary | ||||

| (-2) Log-likelihood | 80.748 | |||

| Accuracy of prediction: Overall (%) | 97.3% | |||

| Pseudo R-square | ||||

| Cox & Snell R Square | .624 | |||

| Nagelkerke R Square | .737 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).