1. Introduction

According to the United Nations, Japan was the world’s first super-aging society in the 1990s [

1], with low birth rates and high life expectancies plaguing it [

2]. Consequently, Japan’s population began to decline in 2008 [

3]. Demographic aging is a global trend with significant implications for human development in the present century. Global life expectancy at birth was only 46.5 years in 1950; however, it exceeded to 60 years in 1979, 65 years in 1996, and 70 years in 2010, respectively. The average global life expectancy in 2022 (predicted value) was 71.7 years, which is expected to exceed 75 years by 2033 and 80 years by 2077, respectively [

4]. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that the number of people aged 65 years and above, as a proportion of the global population, was 5.1% in 1950, and is expected to reach 25.1% by 2050 in its member states [5]. This indicates that global trends seem to be following Japan’s social changes. Therefore, studying the country’s current situation may be useful for understanding the world’s aging society.

Plouffe and Kalache reported the efforts of the World Health Organization (WHO) in assisting and promoting cities to become more “age-friendly” [

6] through the Global Age-Friendly Cities Guide: Checklist of Essential Features of Age-Friendly Cities [

7]. Recently, Dikken et al. developed an Age-Friendly Cities and Communities Questionnaire (AFCCQ) [

8], consisting of 23 questions, which is psychometrically valid and measures the experiences and opinions of older residents regarding the age-friendliness of their residential localities. Additionally, as buildings constitute cities and towns, architectural designers and builders are obliged to take an interest in the living environment surrounding the buildings because of their occupational requirements. To investigate how people belonging to the occupations mentioned above evaluate age-friendly indicators in cities and towns in which they reside, we evaluate the age-friendliness of Japanese cities and towns built by resident architects and constructors, using them as subjects.

2. Materials and Methods

From August 1, 2021, to September 30, 2022, e-mails explaining the research and Google forms containing the survey questions were sent to the architectural firms and design offices whose email addresses were publicly available in Japan. The subjects included people in town development-related occupations (architects, constructors, civil engineering, interior decoration companies, people involved in city planning, and so on), above 20 years of age, who could access and respond to information online through smartphones or personal computers, during the above-mentioned period. The survey questionnaire, based on the AFCCQ, consisted of 23 questionnaire items in English, juxtaposed with a Japanese-translated version, which participants had to evaluate using a 5-scale classification of “Totally disagree” (-2), “Disagree” (-1), “Neutral” (±0), “Agree” (+1), and “Totally Agree” (+2).

The primary endpoints were the AFCCQ total score (hereafter, Score) consisting of 23 questionnaire items and 9 domains. Research subjects were selected based on their place of residence (up to the municipality), age, gender, educational history, period of living in the current location, place of residence five years ago, type of residence, number of household members, presence/absence of support/nursing care required and type of certification, presence/absence of chronic illness, use of a wheeled walker or wheelchair, and so on. The 9 domains included “public spaces and buildings,” “transportation,” “housing,” “social participation,” “respect and social inclusion,” “civic participation and employment,” “communication and information,” “community support and health services,” and “financial situation.” “Respect and social inclusion” were evaluated on two negative questions and their values were reversed since the other 21 questions were positive. The data for each municipality were obtained from the 2020 National Census [

9], and the public notice of January 2021 land prices [

10]. In addition, data about “municipalities at the risk of disappearing due to depopulation” were obtained from the report of the Japan Policy Council [

11]. The statistical analysis software IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 was used to analyze data, and Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test were performed to confirm the differences among residential municipalities. Contiguous quantities were summarized by mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were summarized by each segment, separated by groups of depopulated/populated municipalities in the past five years or top 60/worst 60 municipalities at the land price or nuclearization.

Additionally, a diagnostic performance plot (DP-plot) analysis [

12] was created, showing the relationship between the Score and sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), and accuracy (AC); a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was also performed. To distinguish between depopulated (positive; +) and populated (negative; -) municipalities by Score, the cut-off point was set to zero because Score = 0 represents “Neutral” based on the definition of the Score. Data management was conducted at the Nagoya Institute of Technology, and information managers, not directly involved in the study, were allocated the task of assigning arbitrary IDs to the data obtained from each target person. These managers checked their anonymization status. Thereafter, the dataset was sent to the Biostatistics Center of Kurume University for statistical analysis. To fairly evaluate the results, we built and implemented a system where people in charge of data management and statistical analysis were separated. In addition, we created a subject distribution map based on a blank map and location information obtained from 3kaku-K (

https://www.freemap.jp/free.html) and the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (

https://maps.gsi.go.jp/help/intro/school/blankmap.html#link04), respectively.

3. Results

Among the 240 participants who responded to the questionnaire, 199 (82.9%) were males and 41 (17.1%) were females. Occupation-wise, the sample consisted of 145 architects (60.4%), 46 constructors (19.2%), and 49 people in related occupations (20.2%), including those involved in city planning, interior designing, and civil engineering. The age on average (SD) was 57.3 (12.7) years. Furthermore, 163 subjects (77.9%) were <65 years and 77 subjects (32.1%) were equal to or above 65 years. Out of the total number of participants, 83 (34.6%) had a chronic illness and 36 (15.0%) had joint pain. In terms of their education level, 43 (17.9%) had passed graduate school, 153 had completed university (63.8%), 23 had completed junior college (9.6%), and 21 had completed senior high school (8.8%). The average number of household members (SD) was 2.9 (1.4), and the ratio of men to women in these households was 48.9%. Out of the total participants, 98 (40.8%) had older people living with them in their household: 60 had one (25.0%), that included 7 participants living alone (2.9%), 34 had two (14.2%), that included 6 solitaire older pairs (2.5%), and four had three (1.7%), that included one solitaire older trio (0.4%). Six subjects used a wheeled walker or wheelchair (2.5%), and 18 received care services in their household (7.5%). Based on care grades, these subjects were further categorized as follows: four (1.7%) and five (2.1%) belonged to Yo Shien 1 and 2, respectively, and two (0.8%), two (0.8%), one (0.4%), four (1.7%), and zero (0%) belonged to Yo Kaigo 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. The care grade categories used in Japan are defined as follows:

Yo Shien 1: Pre-classifying level 1: A person can perform most of the basic activities of daily living (ADL), including eating, excreting, moving, and bathing on their own. But to prevent the progression of symptoms, some support is required for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as shopping, household chores, medication, and money management.

Yo Shien 2: Pre-classifying level 2: Compared with Yo Shien 1, the ability to perform IADL is reduced. Additionally, some assistance is required for personal care, and a person may require support for movements, such as standing up and walking.

Yo Kaigo 1: The ability to perform IADL is further reduced. From a state of requiring support, the person now requires partial care; maybe unstable when standing up or walking.

Yo Kaigo 2: In addition to Yo Kaigo 1, partial long-term care is required for ADL, owing to forgetfulness and deterioration of comprehension.

Yo Kaigo 3: This condition requires full care for performing ADL and IADL as people experience reduced capacity to eat and bathe on their own.

Yo Kaigo 4: Compared with Yo Kaigo 3, the ability to move is further reduced, and people find it difficult even to excrete on their own, leading to difficulty in leading their daily life without long-term care.

Yo Kaigo 5: The abilities of both ADL and IADL are significantly reduced, requiring full assistance throughout life. People at this stage may face difficulty in communicating or may even be bedridden.

Furthermore, isolation is a big problem in the aging society. Living with pets or moving is an important aspect of their daily life. Out of the total subjects, 57 lived with their pets (23.6%). The dwelling period (SD) of the subjects was 22.9 (17.6) years on average; 196 (81.7%) had spent over five years in the same place, 29 (12.1%) moved from another place, and 15 (6.3%) moved within the same ward in less than five years. Therefore, 211 subjects lived in the same ward or municipality.

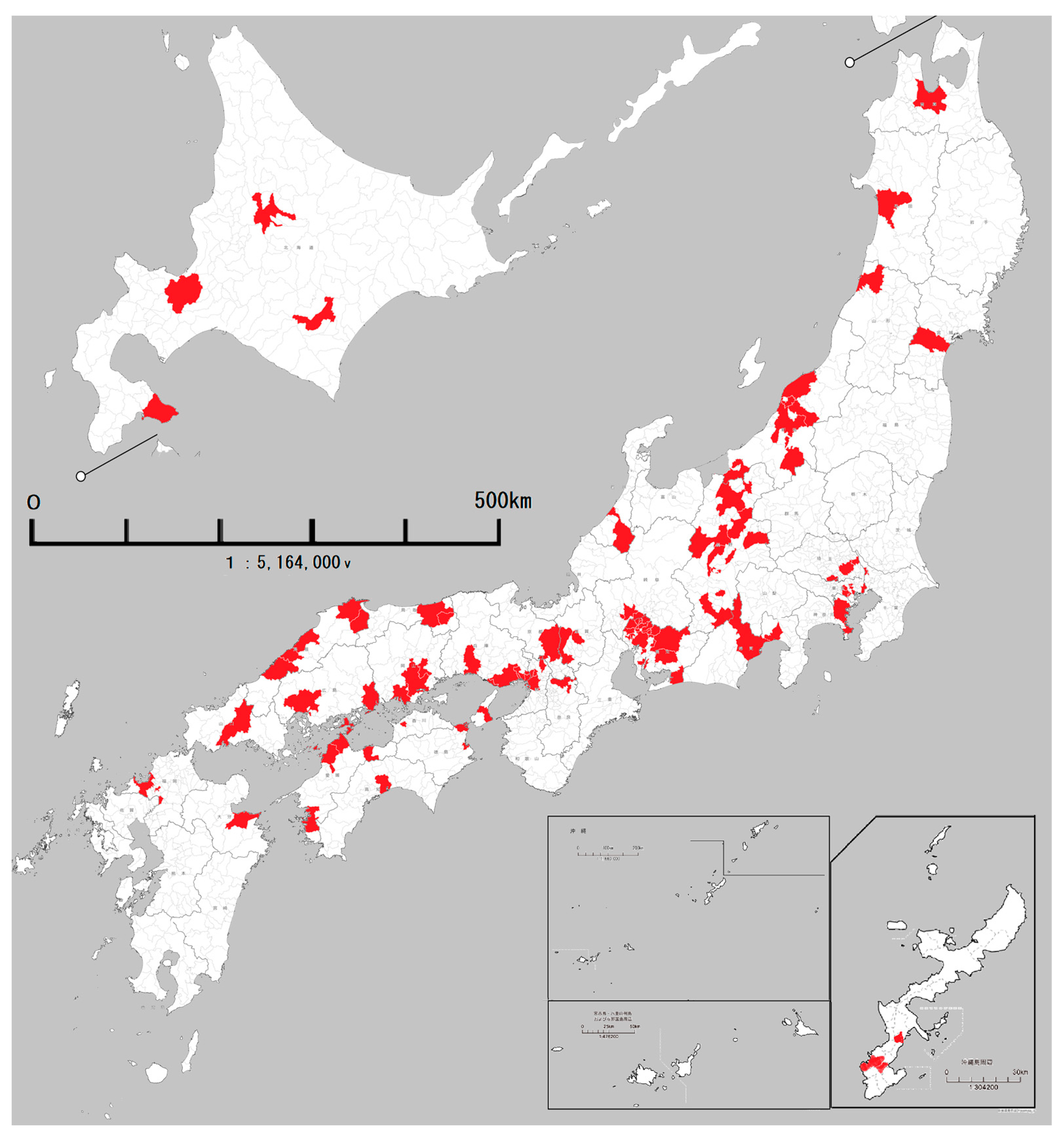

The subjects were spread across 135 municipalities in 35 prefectures, with the municipalities being distributed all over Japan, from Hokkaido in the north to the Okinawa Prefecture in the south (

Figure 1).

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 135 municipalities. The municipalities consist of rural and urban populations having densities under 100 persons/km

2 and over 10,000 persons/km

2, respectively. In 109 municipalities (80.7%), the nuclear family ratio per household was more than 50%. Additionally, in 125 municipalities (92.5%), the aging ratio was above 20% in both rural and urban areas. However, the fluctuation rate of households in Japan has increased over the past five years [

9], with the number of households increasing in 119 municipalities (88.1%), and decreasing in 16 (11.9%). The trend of living alone has increased across all generations.

Population fluctuations represent modern values, while, land prices represent the future. Since the national census reflects an aging society, a survey of single-person households, aged 65 years and above, may have been conducted [

9]. Therefore, we decided to focus on the dynamic population change in the past five years, land places in residential areas, and above 65 years of age single-household ratio per total households in the aforementioned municipalities.

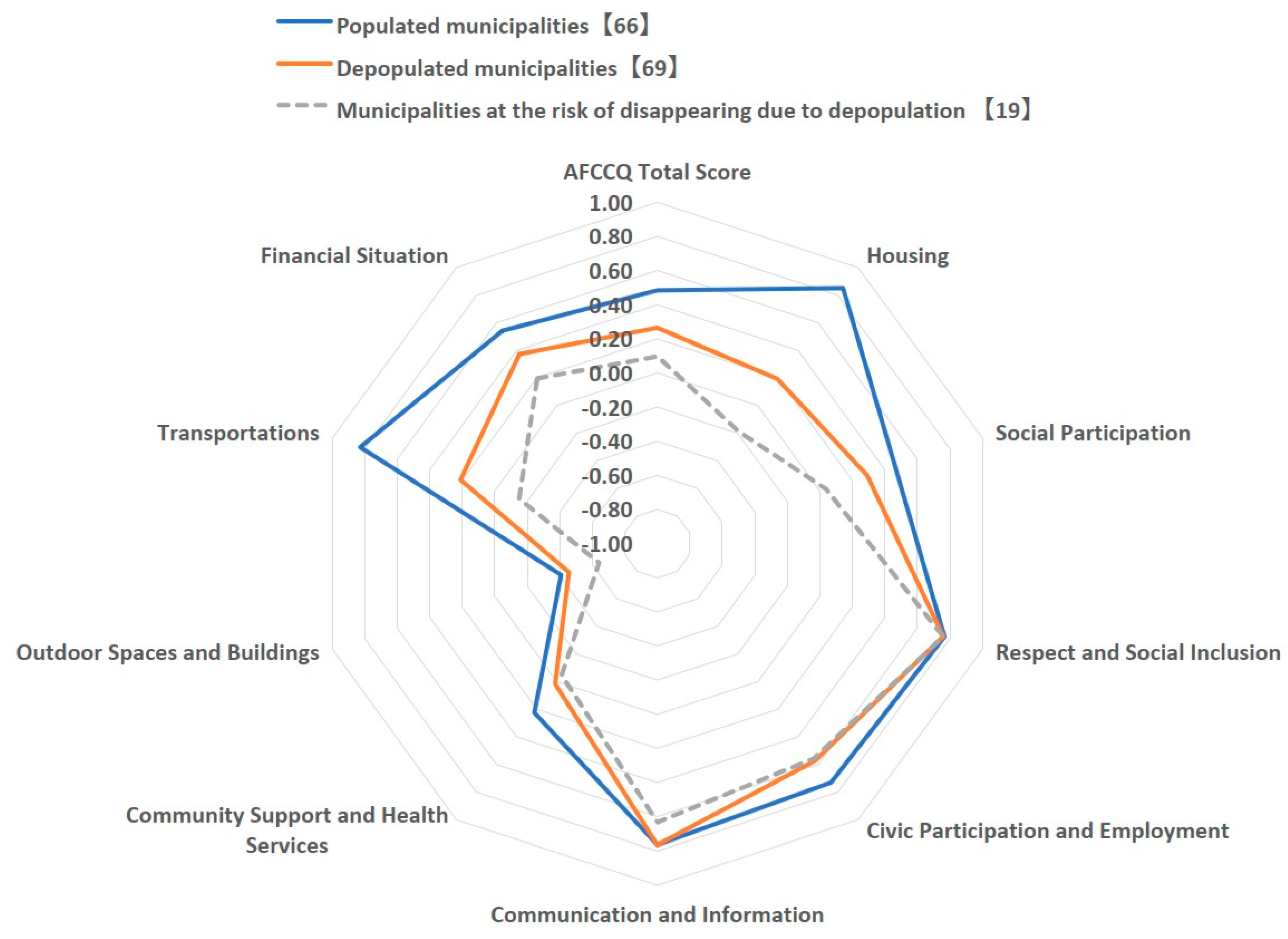

Table 2 shows that the average population and depopulation ratio was +3.09±0.38% in 66 populated municipalities and -2.81±0.27% in 69 depopulated municipalities, respectively, during the past five years. Architectural designers and constructors negatively rated Japanese municipalities with regard to “outdoor spaces and buildings.” The evaluation of “Score,” “housing,” and “transportation” of the 69 depopulated municipalities in the past five years were significantly lower than those of the 66 populated ones (p < 0.01). Similarly, the evaluation of “community support and health services” was significantly lower in the 69 depopulated municipalities compared with those in the 66 populated ones (p < 0.05).

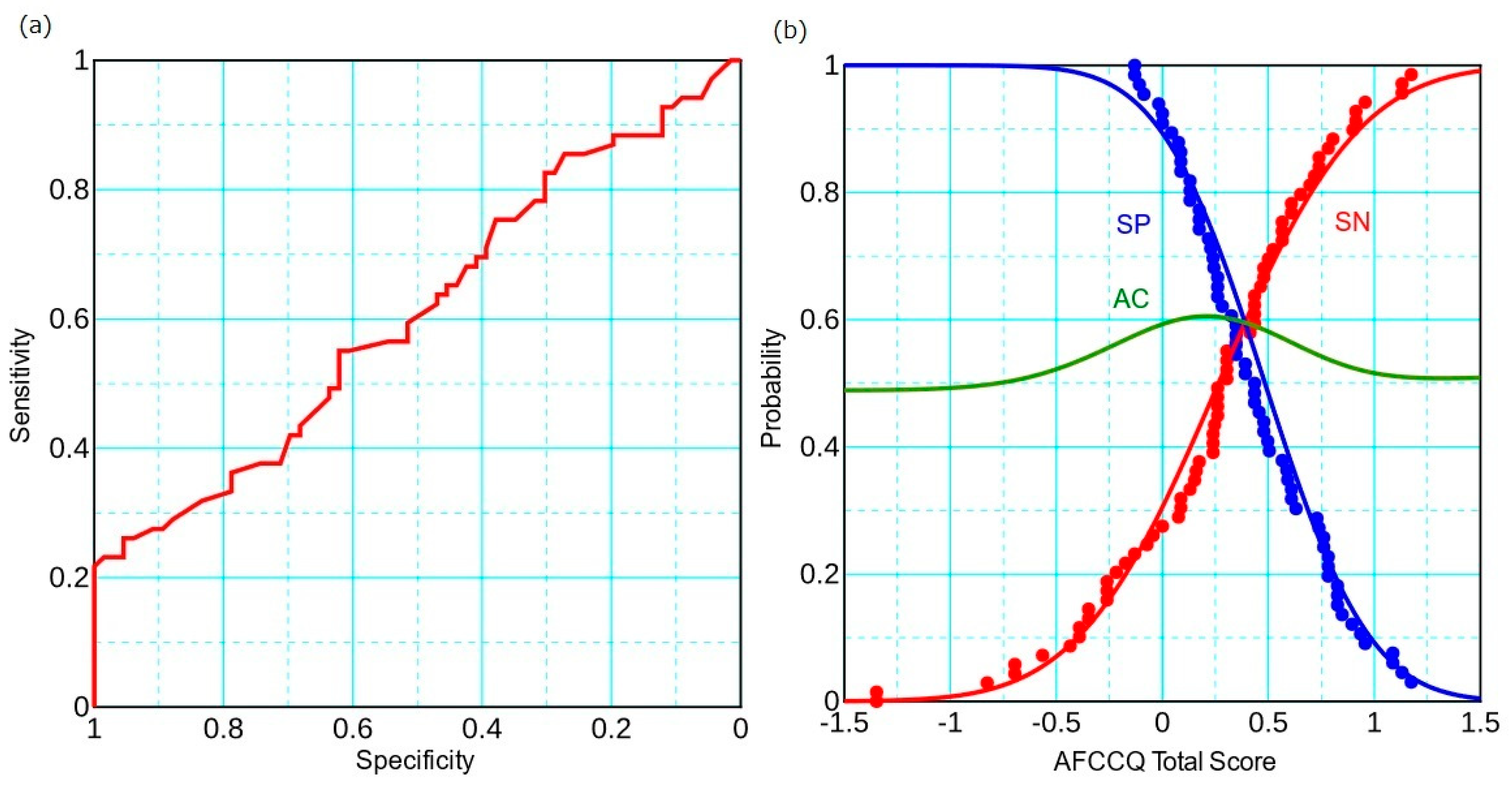

We analyzed the discrimination threshold for depopulation using the AFCCQ total score as a marker (

Figure 2).

Sensitivity (SN), the proportion of the Score ≧ 0 among populated municipalities, is 0.261, and specificity (SP), the proportion of the Score < 0 among depopulated municipalities, is 0.939. In the ROC analysis, accuracy (AC) is 0.593, and the area under curve (AUC) of the ROC curve is 0.609 (p = 0.029).

Japan has 1,799 municipalities; however, the Japan Policy Council reported that by 2040, 896 municipalities would be at risk of disappearing due to depopulation as the number of resident women of childbearing age has halved in these municipalities [

11]. Out of the above-mention municipalities, 19 are present in the 69 depopulated municipalities considered in this study, and they seem to show lower evaluations in all aspects except “respect and social inclusion” (

Figure 3). Each municipality was assessed by 1–9 resident architectural designers and constructors in Japan.

Table 3 shows the differences between the top and worst 50 municipalities having higher and lower land prices. The average unit price in the above-mentioned top 50 municipalities was 8.4 times higher than that in the worst 50 municipalities (p < 0.01). Except in the evaluation of “outdoor spaces and buildings,” the worst 50 municipalities with lower land prices were given negative evaluations in the index of “community support and health services” and “transportation.” The “Score,” “housing,” “transportation” and “financial situation” of the higher land price municipalities were evaluated as significantly higher than those of lower land price ones (p < 0.01). Additionally, the evaluations of “social participation” and “community support and health services” of the top 50 higher land price municipalities were significantly higher than those of the worst 50 lower land price ones (p < 0.05).

The national census, conducted on October 1, 2020, in Japan, reported a change in the ratio of single households, consisting of a single person of 65 years and above per total households in each municipality during the past five years [

9].

Table 4 shows the difference in the evaluation between the worst 50 municipalities with a lower ratio and the top 50 municipalities with a higher ratio of 65 years old and above, single household per total households.

Table 4 shows that the average ratio of the worst 50 municipalities with a lower ratio of 65 years old and above, single household per total households is 9.2±0.2% and that of the top 50 is 14.2±0.3% (p < 0.01). Additionally, the evaluation of “communication and information” in the worst 50 municipalities of the lower ratio of 65 years old and above, single household is significantly higher than that in the top 50 municipalities (p < 0.05), although the difference in the ratio is only 5% between the two groups.

4. Discussion

We observed high (0.939) and low sensitivities (0.261) to depopulation using the Score in the ROC analysis, indicating that although the age-friendly approach represented by the Score is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient to prevent depopulation. The design and arrangement of fine public green spaces promote health and well-being. Social relationships and an adequate environment are key challenges for increasingly population-dense cities. As cities become denser, fine public green spaces become more significant [

13,

14,

15]. Outdoor and indoor environments influence older adults’ mobility, independence, and quality of life. Both the number and the quality of fine public green spaces in the living environment is crucial [

16]. In Japan, where the plains are narrow, setting up outdoor spaces poses difficulties, which is reflected in the low evaluation of “outdoor spaces and buildings.” Resultantly, a declining population and an increased number of single-person households have appeared in Japan. Japan has built a highly convenient social structure that boasts material wealth, typified by the development of convenience stores. To pursue efficiency, Japan may have given up its leeway to raise children, and the declining birth rate and aging population have led to an increasing number of people living alone in Japan.

In the present century, demographic aging and urbanization have become global trends with significant implications for human development. Over the past two centuries, the development of various industries and improvements in social, environmental, and biological factors, including sanitation, housing, human engineering, and medical care, have led to an overall increase in longevity worldwide [

17].

Dr. Albert Schweitzer pointed out that human ethics exist only when you dedicate yourself to helping a suffering life [

18]; however, the ethics are now being called into question. An aging society requires support from others, such as caregivers and helpers. Without opportunities to come in close contact with older people, there are no opportunities to help them. An increase in single-person households may indicate a critical situation, significantly influencing Japan’s future. When Mother Teresa came to Japan, she said, “In Japan, which seems to be rich, isn’t there a hunger in the heart? Being unwanted, unloved, uncared for, forgotten by everybody, I think that is a much greater hunger, a much greater poverty than the person who has nothing to eat. Dear all in Japan, don’t forget poverty, please“. We are entering an era in which Mother Teresa’s words are deeply resonating with people of all ages [

19].

WHO promotes age-friendliness in cities and communities worldwide by proposing policies, services, and structures for age-friendly cities and communities [

20]. They are related to the physical and social environment and are designed to support older people, enabling them to have an active and healthy lifestyle. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the age-friendliness of cities and communities, using transparently constructed and validated surveys, measuring their structure in all respects. Qualitative approaches have been reported to measure and assess the age-friendliness of cities using photo-production [

21] and photo-voice methods [

22], and citizen science research programs [

16,

23]. Various researchers have attempted to develop a more quantitative approach for measuring age-friendliness based on the Checklist of Essential Features of Age-Friendly Cities [

20]. Luciano et al. [

24] proposed a framework for assessing the age-appropriateness of housing using 71 metrics, summarized into eight domains, detecting and identifying physical and non-physical features of a home environment to enable growing older in a place.

Buildings constitute cities and towns. Due to their occupation, those involved in architectural design and construction get connected with people’s lives and, therefore, must take an interest in the living environment around the buildings. In this study, to survey age-friendliness in cities and towns in the best possible way, we combined the assessment of architectural designers and constructors in Japan and a survey based on the AFCCQ because, in addition to being transparent, reproducible, and having a compact volume of items, the AFCCQ is useful for identifying problems and their solutions in aging societies.

5. Conclusions

We surveyed 135 municipalities in Japan to gauge their age-friendliness. They showed Japanese demographic aging, including urban and rural aging. Selecting 240 architectural designers and constructors in Japan, we conducted a survey based on the AFCCQ. The findings highlight that Japan lacks “outdoor spaces and buildings,” besides which a lack of “communication and information” was also observed in cities and towns with a higher rate of single person households aged 65 years and above. Evaluation of “housing,” “community support and health services,” and “transportation” in populated municipalities in the past five years were significantly higher than those in depopulated municipalities. Age-friendliness was significantly affected by land prices. According to the ROC curve analysis, an age-friendly approach, represented by the Score, is necessary to prevent depopulation, making the AFCCQ a powerful tool for evaluating the age-friendliness of municipalities, in combination with the assessment of resident architectural designers and constructors. The lack of an age-friendly approach is one of the reasons why demographic aging, including the extension of healthy life expectancy, and depopulation are observed in coexistence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K. Y. and J. Y.; methodology, K. Y. and K. M.; data curation, K. Y., J. Y., M. M., and Y. L.; statistical analysis, K. M.; writing—original draft preparation, K. Y.; writing—review and editing, Y. L., J. Y. and K. M.; visualization, K. Y.; project administration, K. Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON of “Not applicable” notified by the Ethics Committee of Nagoya Institute of Technology (Receipt number 2021-2 and date of notification: Jun 1st 2021) with a comment of “You can start your study” informed by the window staff of the Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Electronically written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request with the consents of all authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Japanese architectural organizations and their branches, NPO Nagoya Rekishi-Machizukuri-no-Kai and Koko-kai, for helping us with participant recruitment. We are grateful to Norio Sugimoto for advising us on data analysis. We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs/Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/publications/files/wpp2017_keyfindings.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Yamada, K. An acquaintance with an aging society. Soc Sci 2019, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, H. Population aging in Japan: Policy transformation, sustainable development goals, universal health coverage, and social determinates of health. Glob Health Med 2019, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Ageing in Cities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe, L.; Kalache, A. Towards global age-friendly cities: Determining urban features that promote active aging. J Urban Heal 2010, 87, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dikken, J.; van den Hoven, R.E.M.; van Staalduinen, W.H.; Hulsebosch-Janssen, L.M.T.; van Hoof, J. How older people experience the age-friendliness of their city: Development of the age-friendly cities and communities questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics of Japan. Census on Oct. 1st 2020. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?tclass=000001037709 (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/totikensangyo/totikensangyo_fr4_000432.html (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Japan Policy Council. List of 896 municipalities at the risk of disappearing due to depopulation until 2040 in Japan. Available online: http://www.policycouncil.jp/pdf/prp03/prop03_2_1.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023) and https://mainichi.jp/articles/20140509/mog/00m/040/001000c (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Nakamura, A.; Kaneko, N.; Villemagne, V.L.; Kato, T.; Doecke, J.; Doré, V.; Fowler, C.; Li, Q.; Martine, R.; Rowe, C.; et al. High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2018, 554, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grose, M. Changing relationships in public open space and private open space in suburbs in South-Western Australia. Landsc Urban Plan 2009, 92, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoopera, P.; Borufftb, B.; Beesleya, B.; Badlandc, H.; Giles-Coric, B. Testing spatial measures of public open space planning standards with walking and physical activity health outcomes: Findings from the Australian national liveability study. Landsc Urban Plan 2018, 171, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human-environment interactions in urban green spaces: A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrie, H.; Soebarto, V.; Lange, J; Mc Corry-Breen, F. ; Walker, L. Using citizen science to explore neighbourhood influences on ageing well: Pilot project. Healthcare 2019, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luepker, R.V. Increasing longevity: Causes, consequences, and prospects. In Longer Life and Healthy Aging, International Studies in Population; Yi, Z., Crimmins, E.M., Carrière, Y., Robine, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, A. Aus meinem leben und denken (Waga Seikatsu to Shisou yori), Hakusui-sha (Publisher), Tokyo, Japan; 1995; pp. 188–189.

- Oki, M. Mother Teresa Full of Love (Afureru Ai -overflowing love-), Koudan-sha (Publisher), Tokyo, Japan; 1984; pp. 247–248.

- World Health Organization. Measuring the Age-Friendliness of Cities: A Guide to Using Core Indicators; World Health Organization: Genova, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof, J.; Dikken, J.; Buttģieģ, S.C.; van den Hoven. R.F.M.; Kroon, E.; Marston, H.R. Age-friendly cities in the Netherlands: An explorative study of facilitators and hindrances in the built environment and ageism in design. Indoor Built Environ 2020, 29, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.W.; Chan, H.Y.; Chan, I.K.; Cheung, B.Y.; Lee, D.T. An age-friendly living environment as seen by Chinese older adults: A “photovoice” study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016, 13, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.C.; King, D.K.; Banchoff, A.; Solomonov, S.; Ben Natan, O.; Hua, J.; Gardiner, P.; Goldman Rosas, L.; Rodoriguez Espinosa, P.; Winter, S.J.; et al. Employing participatory citizen science methods to promote age-friendly environments worldwide. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, A.; Pascale, F.; Polverino, F.; Pooley, A. Measuring age-friendly housing: A framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of the MDPI and/or editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).