Introduction

Nursing care presents challenges such as uncertainty, that is inherent in life; Merle H. Mishel (1988) defined nursing uncertainty as “the inability to determine the meaning of events related to the disease”; uncertainty is the cognitive state in which the individual cannot structure an event due to lack of signals(1) or is unable to predict accurate results that provoke a series of emotions.(2) These difficulties in adapting to the situation and channeling emotions can become negative and affect mental health.

Health professions, especially nursing, present uncertainty due to the complexity of health systems, the tasks to be performed and because they are a bridge of contact between users and the rest of the system. In nursing, uncertainty can arise during daily practice and decision-making, which can lead to burnout and decreased job satisfaction that compromise outcomes and quality of care.

Uncertainty during clinical practice appears when there is insufficient information to predict the prognosis or the outcomes of an intervention. As a precursor of uncertainty there is the absence or lack of information that prevents the construction of one’s own references, addressing the problem with solutions built by experiences, knowledge, and intuitions, providing security;(3) the feeling of little security contributes to worry and anxiety even in contexts recognized as safe.(4) The most stressful clinical factors are complexity, importance, variety and variability of interventions, burden of care, degree of knowledge and professional experience.

Emotionally, personal experience of uncertainty often is a negative feeling and can influence thoughts, feelings, or behaviors(5,6) causing stress, anxiety, exhaustion, fear, worry and even avoiding decision making.(7,8) Behaviorally, it can cause interprofessional communication problems or with patients, leading to erroneous and harmful diagnoses.(8,9) Cognitively, it can generate from excessive worry to avoidant behaviors, as is linked to anxiety (behavioral patterns characterized by subjective feelings, cognitions, tension, and physiological activation as a response), constituting a state assimilable to fear.(3) Uncertainty and anxiety appear anticipatorily due to ignorance of threatening future events.

Low security feelings produce the appearance of worry and anxiety in contexts recognized as safe and/or habitual.(4) Being a dynamic and changing feeling over time, the reactions arising from uncertainty can be modified,(3) developed and improved consciously appearing a tolerance to uncertainty, understood as “the ability to act without having all the necessary information, nor the accuracy of the result, nor the security of the success of our actions”.(10) Uncertainty tolerance is an adaptive coping that seeks solutions, new plans and information about the uncertain event, accepting itself as another part of the daily routine and in positive force when acting professionally.(3) People with low tolerance for uncertainty feel overwhelmed and are unable to adapt, reacting with avoidance of the situation or ignoring these feelings of uncertainty;(5,6) these people perceive the unexpected as a threat, experiencing stress and avoiding confused impulses.(11) Uncertainty tolerance is based on a balance between negative and positive responses: imbalance can trigger negative responses,(12) as well as effects and reactions triggering decisions that may harm one’s own health and the patient’s health.(13) In health care facilities, uncertainty is associated with a higher rate of burnout, frustration, and avoidance of responsibility,(8,11) reflecting a lower perceived quality of life, a decrease in professional satisfaction (both in their functions and in professional relationships) and a decrease in professional self-care.(3,6) In professionals with good tolerance to uncertainty, insecurity manifests a dynamic state of self-evaluation perceived as positive in relation to care and safety, providing better care during basic nursing care due to adaptation in the search for solutions.(7)

The Physicians’ Reactions to Uncertainty (PRU) scale quantifies the tolerance to uncertainty in medical professionals, measuring their reactions to uncertainty and its influence on the patient.(14) This scale quantifies the capacity to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty, which have a major impact on clinical practice and healthcare.(14)

In nursing, communication is the main tool to establish a relationship and a bond with the patient, his relatives and all the professionals involved.(8,17) This communication is part of daily work: listening, talking, and responding to concerns and questions from patients and their environment. Correct interactions and the exchange of objective information facilitate the success of the intervention.(17) Without an adequate professional-patient transfer, three types of comprehension errors can occur: knowledge (distrust of the sender’s knowledge), content (lack or lack of training of the sender) or transmission (perception of lack of veracity in the mode of transmission of the message).(18)

Improving collaboration between professionals allows solving problems, developing cohesion, informing, and updating information and individually improves awareness of responsibility by providing quality care and personal and professional satisfaction. Communication between service professionals occurs during the transfer of information between shifts in meetings at the beginning of the workday and at the end of it, when sharing updated patient information with the next shift.(19) In our environment, the time to share this information is known by different names, such as “shift pass”, “shift delivery”, “shift change”, “guard pass” or “patient transfer” and has great importance to be able to provide comprehensive nursing care, guarantee continuity of care and safety in care.(20) A work shift is characterized by a variety of ideas, beliefs, values, attitudes, and aptitudes: establishing constructive collaboration and common collective thinking will benefit the results. The objectives of these meetings are the coordination and prioritization of care with critical reasoning,(6,21) highlighting the most important attentional aspects, establishing interactions aimed at restoring and preserving the health of the people served based on respect and the needs of each patient.

Written clinical courses support oral communication and reflect important aspects, but they usually contain medical terms, acronyms and specific language that can lead to confusion (due to similarity with others, the context used or being unknown),(23) hindering nursing care and increasing uncertainty.(22) Transferring information directly in these joint meetings allows us to know the status and evolution of the patient to update nursing care adapting it to each unmet need. Sharing information generates positive feedback by exposing issues and resolving them through mutual learning.(19) Information transfer requires time, assertive communication, active listening, non-verbal and verbal communication (optimizing objective information, the evolution of each patient, modification of treatment and procedures performed).(22) If biopsychosocial information is not accurate, timely, complete, and relevant, defects in comprehensive care may occur. Improved information transfer improves communication and reduces the omission of critical information.(20) Information transfer between professionals is critical, but it has a weakness that is not to have a pre-established and protocolized structure; its standardization has been proposed as a strategy for the efficient use of health system resources and guarantee of reliability.(6)

“Shift passing” between shifts is widespread; in Intensive Care Units (ICUs), due to their specificity and complexity of tasks, this intraprofessional communication is also conducted between members of the same shift (“intrashift pass”), not only between correlative shifts (“shift pass”).(24–26) The care activity in the ICU is marked by uncertainty and the communication of the nursing team can condition the care results: omission of information could seriously harm hospitalized people’s health, particularly in clinically unstable patients.(6,25) To implement the intrashift pass can allow to avoid uncertainty and disparity of points of view or interests among professionals,(27) using a participatory communication model and favoring involvement towards common objectives. The decentralization and the low hierarchy inside them favor the contribution and involvement of the team in objectives, plans and achievements contributing to greater satisfaction and personal independence when feeling the support of the group. The intrashift pass provides the team with knowledge of patients (diagnosis, treatment, needs and interventions) quickly and thoroughly, facilitating open discussion of each situation to coordinate interventions and providing a broad and general vision of the service.(19)

In nursing, work performance can increase, and uncertainty can be reduced, helping to meet psychological needs, strengthening work designs, and promoting participation through effective intraprofessional communication that solves routine tasks with concrete and immediate results.(5,24)

The objective of this study is to investigate the degree of uncertainty in the nursing services of our environment and to evaluate the perception of the implementation of an intrashift pass as a proposal for improvement.

Material and Methods

Ad-hoc survey distributed through social networks for nursing care professionals and Auxiliary Nursing Care Technicians (ANC). Variables: sex, age, qualification, service or unit, work experience, PRU scale (Physicians’ Reactions to Uncertainty) and additional question on the perception of the intrathoracic pass as a tool to improve uncertainty.

The sample included in the study was selected by convenience sampling, with anonymous and voluntary participation in the survey, and informed consent obtained through acceptance of the terms and conditions of the survey itself. “This study was approved by the scientific review commision of Escuelas Universitarias Gimbernat (attached to the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona) in January 15th 2023, with the identification code #23001NC.”

PRU scale: 15 items, two dimensions with two categories, respectively: 1-Stress from uncertainty (subcategories Anxiety due to Uncertainty, 5 items, and Concern About Bad Outcomes, 3 items); 2-Reluctance to Disclose Uncertainty and Mistakes (subcategories Reluctance to Disclose Uncertainty to Patients, 5 items, and Reluctance to Disclose Mistakes to Physicians, 2 items).(11) Each item scored on a 5-point Likert scale [Strongly disagree (1 point), Disagree (2 points), Neither agree nor disagree (3 points), Agree (4 points), Strongly agree (5 points)]. The result of each subcategory is obtained from the sum of its items (items 4, 9, 10 and 12 score inversely). The maximum score is set at 90 points when using the Likert scale based on 6 points for each item, or 75 points (responses scored from 1 to 5), simplifying and clarifying the answers. The results in literature use to reflect higher scores in physicians with greater concern about poor care outcomes and greater reluctance to disclose uncertainty, among younger and less experienced professionals.(16) Responses with multiple options selected were excluded and considered invalid responses.

Statistical analysis was performed using MicrosoftTM Excel® and IBMTM SPSS v.27 software. A descriptive analysis of the variables (age, sex, qualification, service, experience, shift pass between shifts and intrashift, PRU scale) and inferential variables was carried out using parametric tests: Pearson correlation (relationship between uncertainty and years of professional experience and relationship between uncertainty and age), t-distribution (uncertainty by professional groups) and ANOVA (differences in uncertainty between different care services). Statistical significance was considered with a p-value=0.05, and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

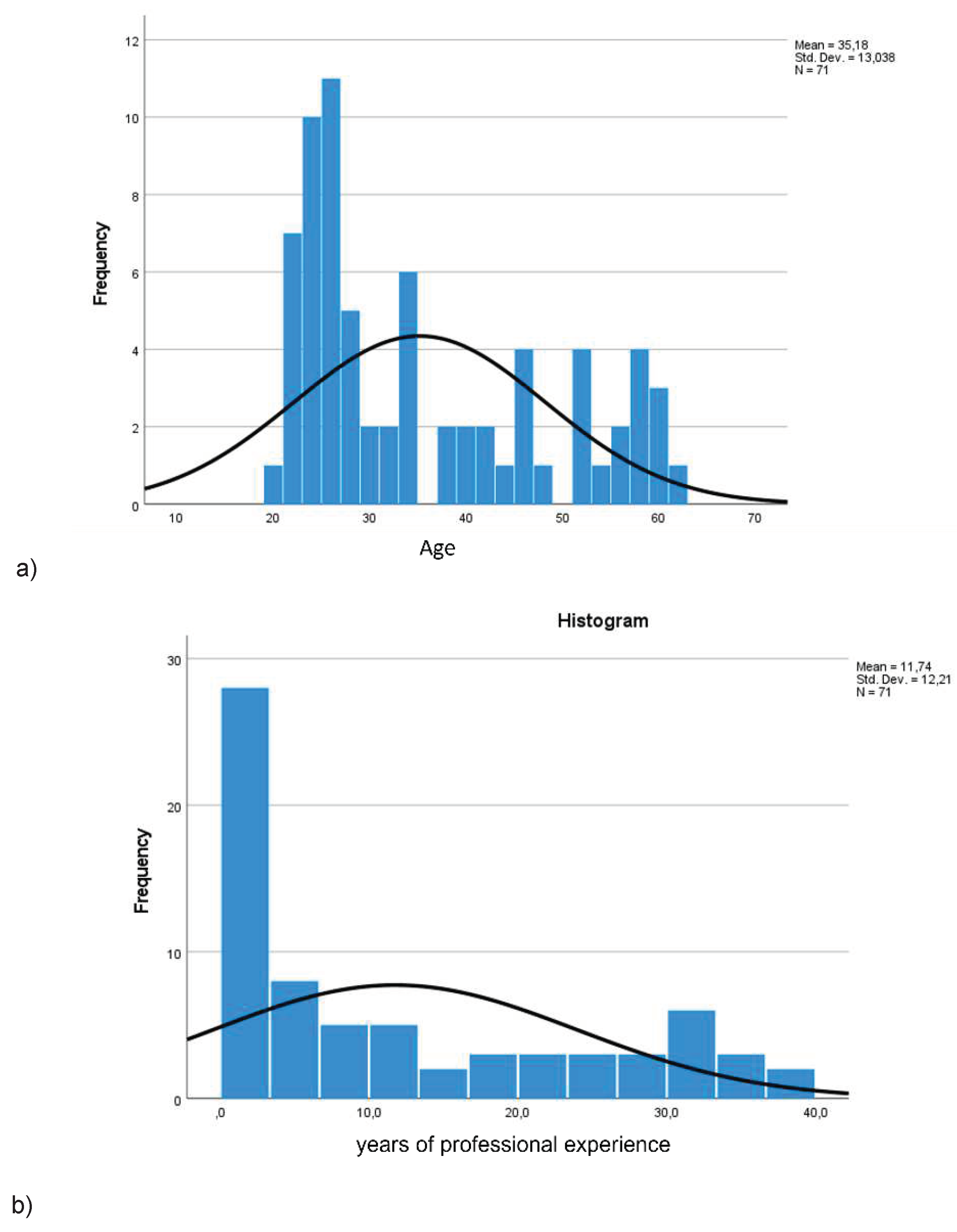

The sample was collected during the first quarter of 2023 through communication networks between professionals. The final sample included a total of 71 participants (61 nurses, 85.9% and 10 TCAEs, 14.1%,

Figure 1) from health centers in our region. 90.1% were women and 9.9% were men (age: mean=35.18 years, minimum=20, maximum=61, standard deviation SD=13.04) (

Figure 2a). The average professional experience was 11.74 years (SD=12.21) and most (43.7%) had less than four years of professional experience (

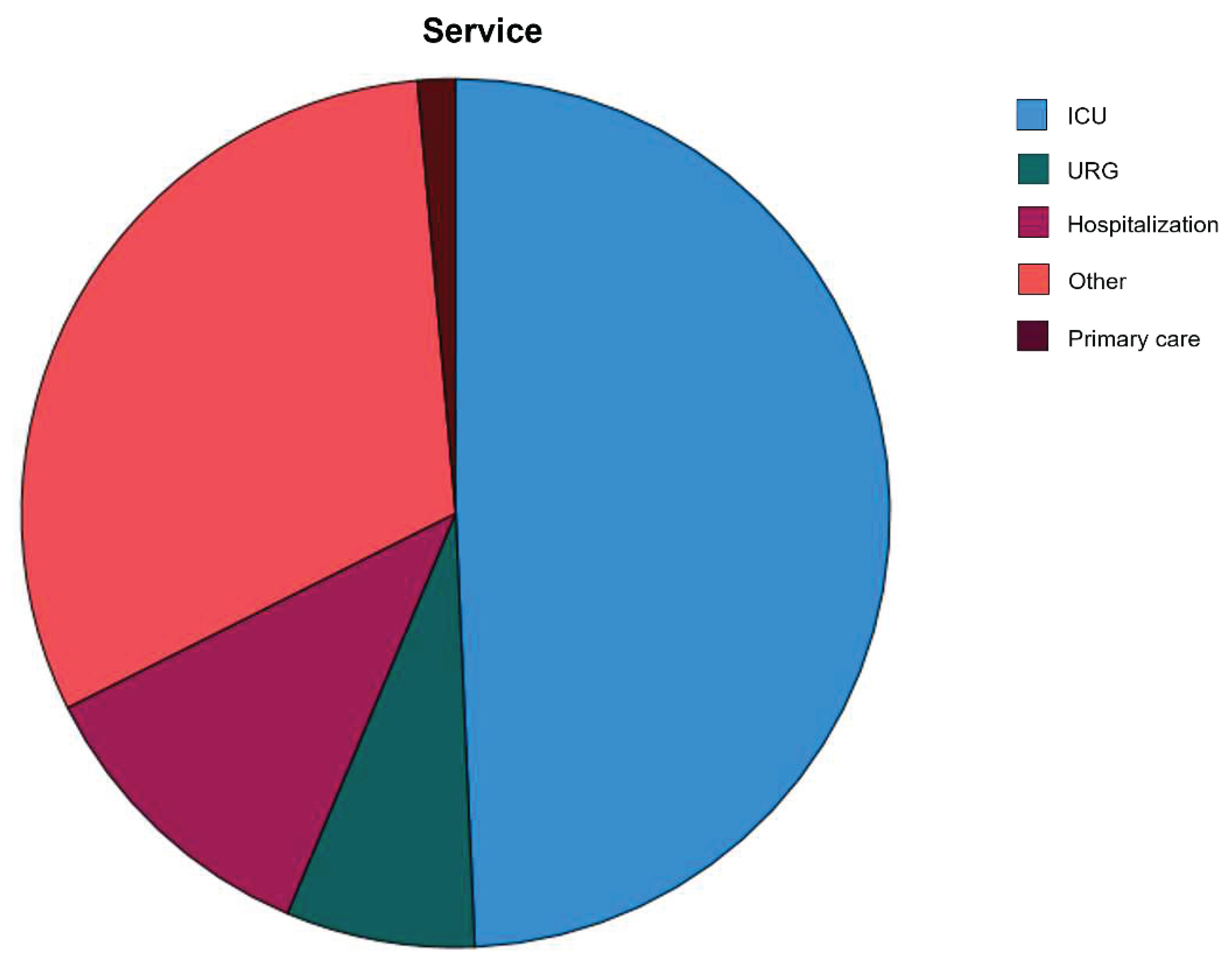

Figure 2b). The most represented services and units were ICU (49.3%), Hospitalization (11.3%), Emergency (7.0%), Primary Care (1.41%) and other services (31.0%) (

Figure 3). 84.5% of the participants performed reunions between shifts in their services, while 63.4% also performed reunions in the same shift (intrashift) mostly belonging to ICU services.

The average level of uncertainty (total PRU scale) gave a mean of 27.99 points (37.32% of the maximum score, SD=7.5), with no significant differences between genders (women=28.3, SD=7.61; men=25.3, SD=5.44; p=0.347), between professions (Nursing=27.9, SD= 7.54; CAE=28.2, SD= 7.61; p= 0.743) or between services or care units.

When analyzing separately each dimension of the PRU scale (

Table 1), results showed that Stress-generated uncertainty obtained a higher score (mean=25.55, 64% of the maximum score; SD=5.24), above the Reluctance to reveal errors and uncertainty (mean=20.07, 57.34% of the maximum score). Analyzing each of the subcategories, the highest score was in Concern for poor results with an average of 9.75 points (65% of the maximum score, SD = 2.71), followed by Uncertainty anxiety that showed an average score of 15.8 points (63.2% of the maximum, SD = 3.05), followed by Reveal uncertainty to patients with an average of 15.46 points (61.84% of the maximum, SD=2.27) and Reluctance to disclose errors to physicians with 4.61 points mean (46.1% of the maximum, SD=1.78) (

Table 2).

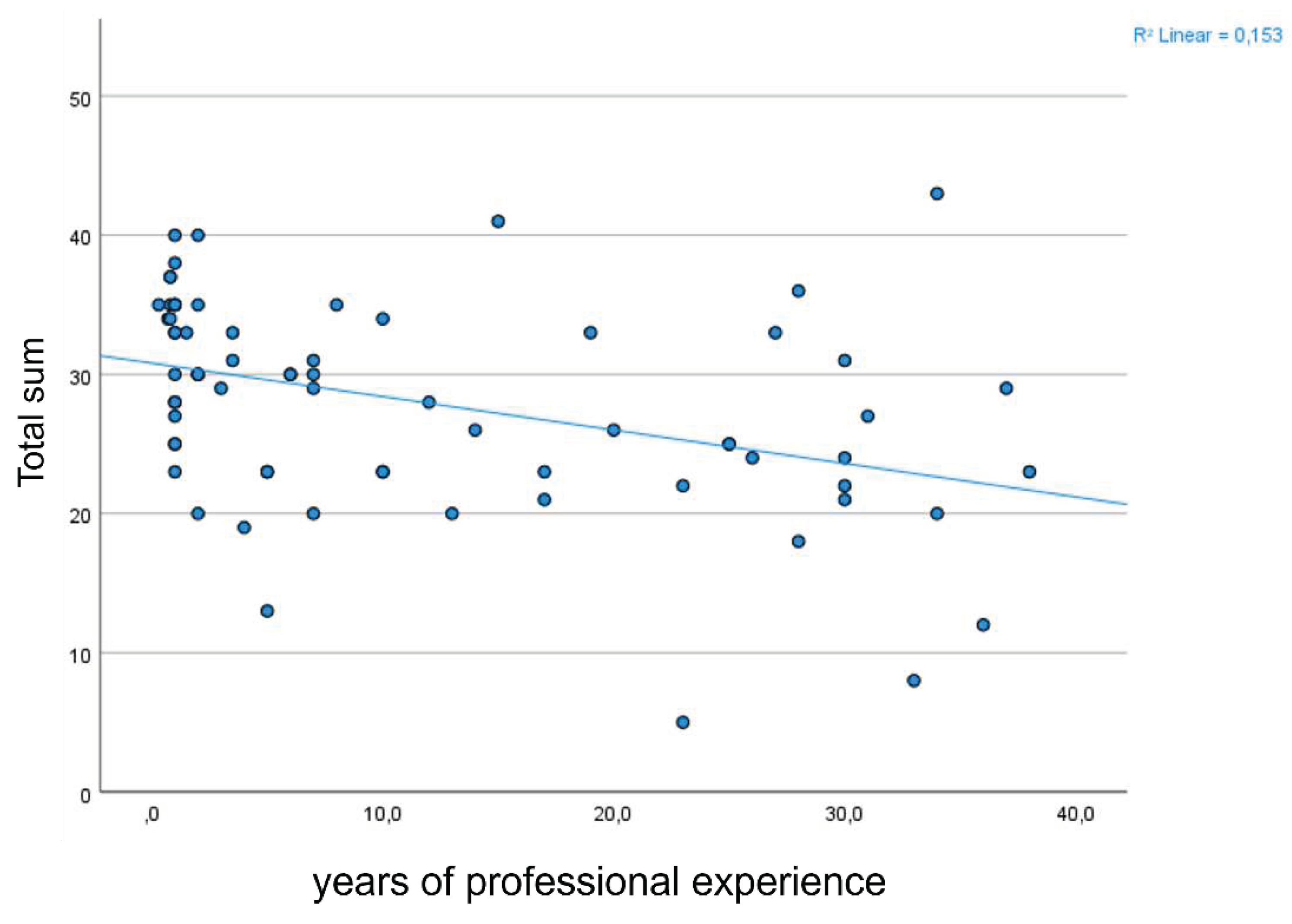

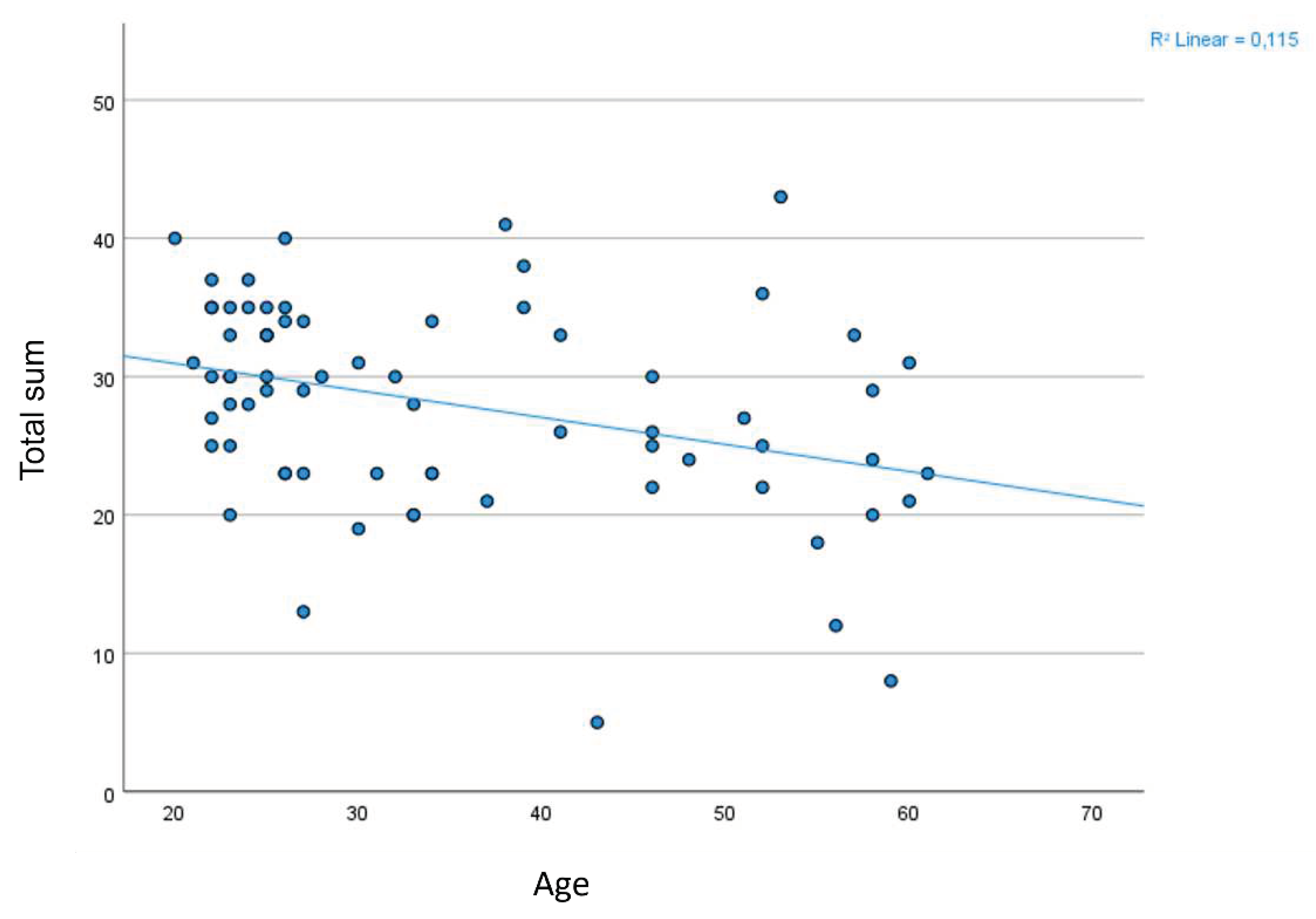

The PRU scale scores showed a statistically significant negative correlation between uncertainty and age (r= -0.339; p=0.004) (

Figure 5), as well as between uncertainty and experience (r=-0.391; p=0.001) (

Figure 6), showing that the older participants and the most experienced reflected less uncertainty: the younger and more inexperienced are more at risk of suffering negative manifestations (stress and anxiety) due to uncertainty.

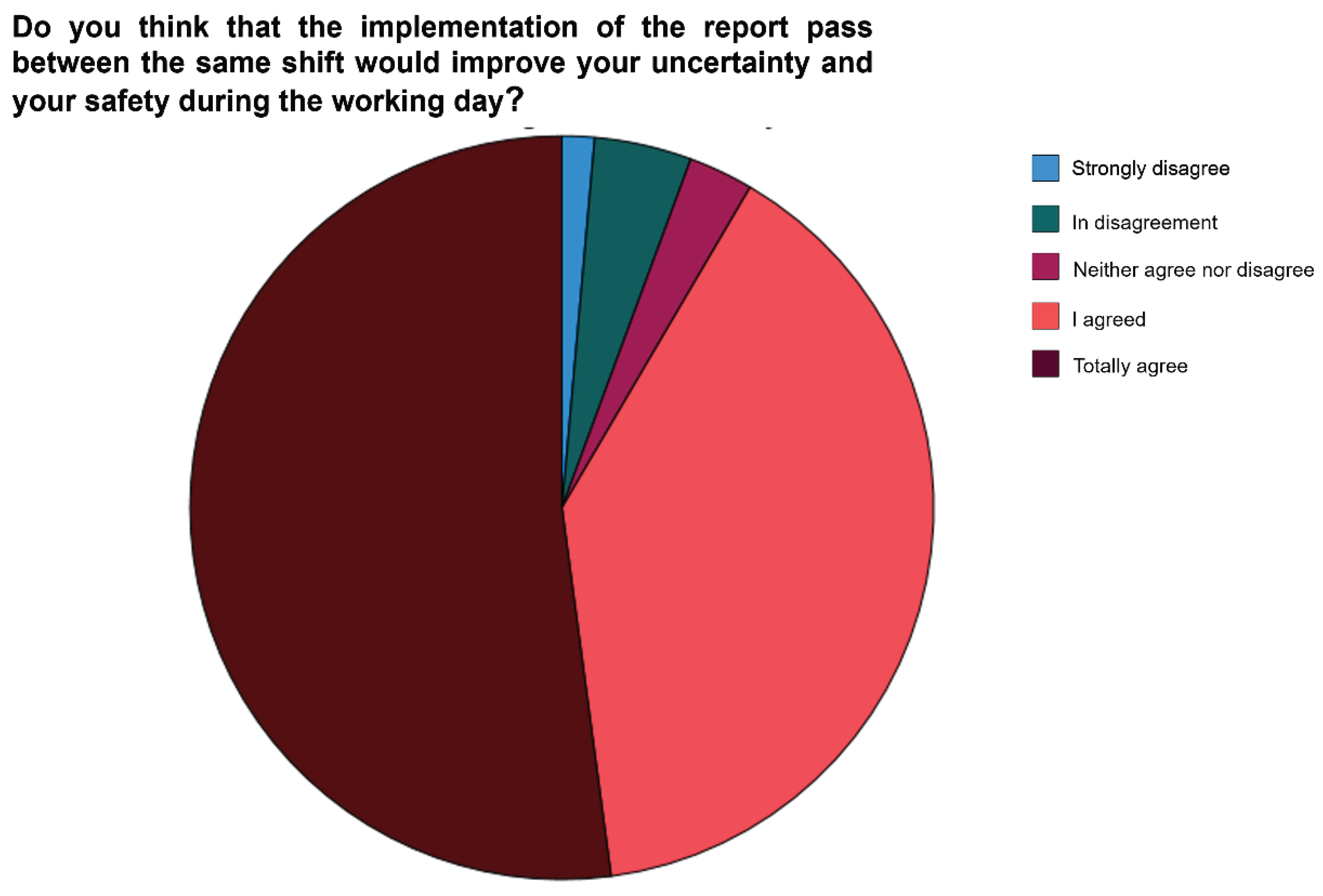

91.6% answered affirmatively to the question about whether the intrashift pass would improve the perceived uncertainty during the work shift (39.4% agreed, 52.1% strongly agreed (

Figure 4); Only 1.41% strongly disagreed with the establishment of the intrashift pass as a tool for reducing uncertainty (

Table 3).

Figure 4.

Graph of the perception that the implementation of an intrashift pass would positively influence professional uncertainty.

Figure 4.

Graph of the perception that the implementation of an intrashift pass would positively influence professional uncertainty.

Figure 5.

Correlation between professional experience (years of experience) and uncertainty (PRU score).

Figure 5.

Correlation between professional experience (years of experience) and uncertainty (PRU score).

Figure 6.

Correlation between age (years) and uncertainty (PRU score).

Figure 6.

Correlation between age (years) and uncertainty (PRU score).

Limitations

This study possibilities of generalization may be limited by the sample size and by the hospital origin of the participants, as well as their small territorial diffusion. Most respondents are women, agreeing with the reality of the nursing profession, but it prevents comparison by gender due to the low representation of men in the sample.

The tool used as a variable (PRU scale) is a validated scale created for physicians and residents, so it contains some very specific item in this field, which could generate that some question was inappropriate for nursing; however, in the absence of a specific validated scale on nursing uncertainty, the questions were considered sufficiently appropriate for the type of participants.

Discussion

Although the sample was limited in number and origin, the results of the study can be interesting because participants belonged to both public and private health organizations and subsidized centers, obtaining information on different work methodologies, working conditions and schedules. The fact that no significant differences were detected between genders and units of origin supports the idea that the results are uniformly shared among the participating services. 85.9% of the participants were women, in line with the greater female participation of the nursing profession. The average professional experience was 11.74% years, highlighting the greater participation of younger professionals by participating to a greater degree in professional dissemination networks through the Internet (43.70% of participants had less than four years of professional experience 63.40% of the participants already performed the “intraturn pass” in their jobs; probably it is because ICU was the most represented service (49.3%), since in this service an additional pass to the “shift pass” (between consecutive shifts) is conceived as of greater importance due to the complexity of the actions in this care area. Our results found no significant differences between different care services, as did the background of an Italian study (28) that found no significant differences in the manifestation of uncertainty between medical specialties.

Uncertainty is generated in all nursing professionals during their daily practice, evidencing in our sample intermediate levels of uncertainty (mean=27.99 out of a maximum of 75 points, SD=7.50, representing 37.32% of the maximum score), with no statistically significant differences between ages, qualifications, or services of origin. In other studies carried out on medical graduates, evidence shows that uncertainty tends to be perceived in a higher proportion in women;(29) although our sample included a limited number of men and therefore statistical significance is not sufficient, this trend of higher scores on the PRU scale in women (28.3 points) than in men (25.3 points) seems to be confirmed.

Moderate negative correlations with statistical significance between uncertainty, age and experience are compatible with the available evidence in this regard and are also consistent with clinical experience. The literature shows that younger and inexperienced professionals manifest greater stress and anxiety derived from a lower tolerance for uncertainty.(9,30)

In physicians and residents, the most affected item is the reluctance to disclose errors to others.(11) The results of our study analyzed by subscales and dimensions show, however, a greater concern and anxiety about care outcomes than about the reluctance to report errors, what can be interpreted as very beneficial for the people served because there is no tendency to minimize errors and “protect themselves”, which could be detrimental to patients and their health status.

Addressing issues such as anxiety and stress can improve personal and professional satisfaction, providing more satisfying nurse-patient care with quality care. There are no standardized references on specific strategies or tools, but the importance of improving communication to mitigate uncertainty is highlighted,(8) proposing as immediate implementation the creation of a communication space at the beginning of the workday to share uncertainty among professionals and face uncertainty in a productive and satisfactory way, implementing the intrashift pass to support the transmission of information and incorporate it to the existing written record. Promoting the culture of error (not penalizing the communication of errors) in the workplace can enhance individual and collective confidence(13) and can be a constructive attitude.

Uncertainty is a common phenomenon in nursing, regardless of the service or unit, affecting all its members. Sharing doubts, questions, and expectations among professionals on the same shift reinforces the perception of uncertainty and generates positive constructive collaboration at work, being important for the group and for the care results. The “intrashift pass” is perceived as a useful strategy to reduce uncertainty and improve well-being in nursing.

The results of this study, despite their limitations, offer new lines of research on the causes and situations of greater uncertainty to create validated quantification tools and strategies for detection, recognition, and management of uncertainty, partially alleviating the scarcity of data on uncertainty in nursing. Tools and methods that help meet the psychological needs of professionals will combat the low tolerance for uncertainty in contexts of change, offering lines of research to address, improve or solve uncertainty.

The greatest strength of this study is its descriptive nature of the current situation of the nursing profession, collecting the perception and analyzing the results on concerns or needs of its workers, improving the understanding of the phenomenon of uncertainty in nursing. Emphasizing professional communication as a starting point for the investigation of the concept, addressing uncertainty from methods of the discipline, facilitating intervention from the relationship established between its workers.

Therefore, their results also open a new path towards novel studies that provide specific tools or methods to mitigate uncertainty and reduce the symptoms caused in professionals.

FINANCING: None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: None.

References

- Bailey-Donald E, Stewart JL. Merle H. Mishel (1939-actualidad) : teoría de la incertidumbre frente a la enfermedad. Español modelos y teorías en enfermería. 2018;447–62.

- Moreno LYD, Devillalobos MMD, Silva NL. Adaptation and validation of Mishel’s scale of uncertainty against disease in diagnostic procedures. Ciencia y Enfermeria. 2019;25.

- Torrents R, Ricart M, Ferreiro M, López A, Renedo L, Lleixà M, et al. Ansiedad en los cuidados. Una mirada desde el modelo de Mishel. Index de Enfermeria. 2013;22(1–2).

- Cupid, J.; Stewart, K.E.; Sumantry, D.; Koerner, N. Feeling safe: Judgements of safety and anxiety as a function of worry and intolerance of uncertainty. Behav. Res. Ther. 2021, 147, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, E.; Mikkelsen, A. Development and Investigation of a New Model Explaining Job Performance and Uncertainty Among Nurses and Physicians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillen, M.A.; Gutheil, C.M.; Strout, T.D.; Smets, E.M.; Han, P.K. Tolerance of uncertainty: Conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 180, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhomme N, Jego P, Pottier P. Uncertainty management and medical skills: A clinical and educational reflexion. La Revey de Médicine Interne. 2019;40(6):361–7.

- Kalke, K.; Studd, H.; Scherr, C.L. The communication of uncertainty in health: A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1945–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gärtner, J.; Berberat, P.O.; Kadmon, M.; Harendza, S. Implicit expression of uncertainty – suggestion of an empirically derived framework. BMC Med Educ. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulloa, F. Cómo incrementar la tolerancia a la incertidumbre. 361grados.net. 2020.

- Kaplan RL, Busaniche J. INCERTIDUMBRE EN MEDICINA ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL.

- Strout, T.D.; Hillen, M.; Gutheil, C.; Anderson, E.; Hutchinson, R.; Ward, H.; Kay, H.; Mills, G.J.; Han, P.K. Tolerance of uncertainty: A systematic review of health and healthcare-related outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1518–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernero C, Arenas A, Cuadrado E, Luque B. INCERTIDUMBRE Y ORIENTACIÓN HACIA LOS ERRORES EN TIEMPOS DE CRISIS. LA IMPORTANCIA DE GENERAR CONFIANZA FOMENTANDO LA EFICACIA COLECTIVA UNCERTAINTY AND ORIENTATION TOWARDS ERRORS IN TIMES OF CRISIS. THE IMPORTANCE OF BUILDING CONFIDENCE, ENCOURAGING COLLECTIVE EFFICACY [Internet]. Available online: http://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es.

- Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care. A new measure and new insights. Med Care. 1990;28(8):724–36.

- Lía R. Adaptación transcultural y validación al español de la escala Reacciones de los Médicos ante la Incertidumbre en la ciudad de Córdoba, Argentina [Internet]. Available online: http://trovare.hospitalitaliano.org.ar/.

- Sibbald, M.; Tsang, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Mansoor, M.; Gauthier, S.; Martin, L.; Norman, G.; Blissett, S. Trainee Uncertainty around Intervening When Patients Decompensate. ATS Sch. 2021, 2, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Fernández M, Ignacio-Cerro M, Cervantes-Estevez L, Moro.Tejedor M, Medina-Torres M, Garcí-Pozo A. Comunicación de las enfermeras con los pacientes. Validación de la escala “Interpersonal Communication Assessment Scale” (ICAS). Index Enferm. 2019;28(4):1132–296.

- Pascali-García, R. Errores habituales en las técnicas de comunicación y la relación terapéutica entre el personal de enfermería. Ocronos. 2021;4(12):70.

- Miroslava A, Rosales R, Alfonso J, Castro Y Vázquez P, Isaac F, España R. Características de la comunicación durante el Enlace de Turno de Enfermería: una perspectiva rumbo a la calidad del cuidado Characteristics of communication during the nursing shift link: a perspective towards the quality of care Artículo de Revisión Artículo de Revisión. 2016.

- Smeulers, M.; Lucas, C.; Vermeulen, H. Effectiveness of different nursing handover styles for ensuring continuity of information in hospitalised patients. Vol. 2014, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 2014. [CrossRef]

- Horsky, J.; Suh, E.H.; Sayan, O.; Patel, V. Uncertainty, Case Complexity and the Content of Verbal Handoffs at the Emergency Department.

- Laura A, Sainz G, Ángeles M, Chalezquer G, Pedroarena BJ, Urbiola García A, et al. Comunicación intraprofesional durante el cambio de turno a pie de cama. Percepciones del paciente. Año XXVII. 2020.

- Ihlebæk, H.M. Lost in translation - Silent reporting and electronic patient records in nursing handovers: An ethnographic study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachi KS. On-call communication in intensive care areas in the nursing staff. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnologia. 2022 Jun 5;2.

- Santhosh, L.; Lyons, P.G.; Rojas, J.C.; Ciesielski, T.M.; Beach, S.; Farnan, J.M.; Arora, V. Characterising ICU–ward handoffs at three academic medical centres: process and perceptions. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirgo Rodríguez G, Chico Fernández M, Gordo Vidal F, García Arias M, Holanda Peña MS, Azcarate Ayerdi B, et al. Handover in Intensive Care. Med Intensiva. 2018;42(3):168–79.

- Van-der Hosfadt- Román C, Quiles- Marcos Y, Quiles- Sedastián M. Tecnicas de comunicación para profesionales de enfermería. 1st ed. Generalidad Valenciana. Conselleria de Sanitat, editor. Valencia ; 2006.

- Iannello, P.; Mottini, A.; Tirelli, S.; Riva, S.; Antonietti, A. Ambiguity and uncertainty tolerance, need for cognition, and their association with stress. A study among Italian practicing physicians. Med Educ. Online 2017, 22, 1270009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, G.; Tapley, A.; Holliday, E.; Morgan, S.; Henderson, K.; Ball, J.; Van Driel, M.; Spike, N.; Kerr, R.; Magin, P. Responses to clinical uncertainty in Australian general practice trainees: a cross-sectional analysis. Med Educ. 2017, 51, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, R.; Robinson, O.; Harrison, R.; Mason, S.; Conner, M.; Wilson, B. Are more experienced clinicians better able to tolerate uncertainty and manage risks? A vignette study of doctors in three NHS emergency departments in England. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).