Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

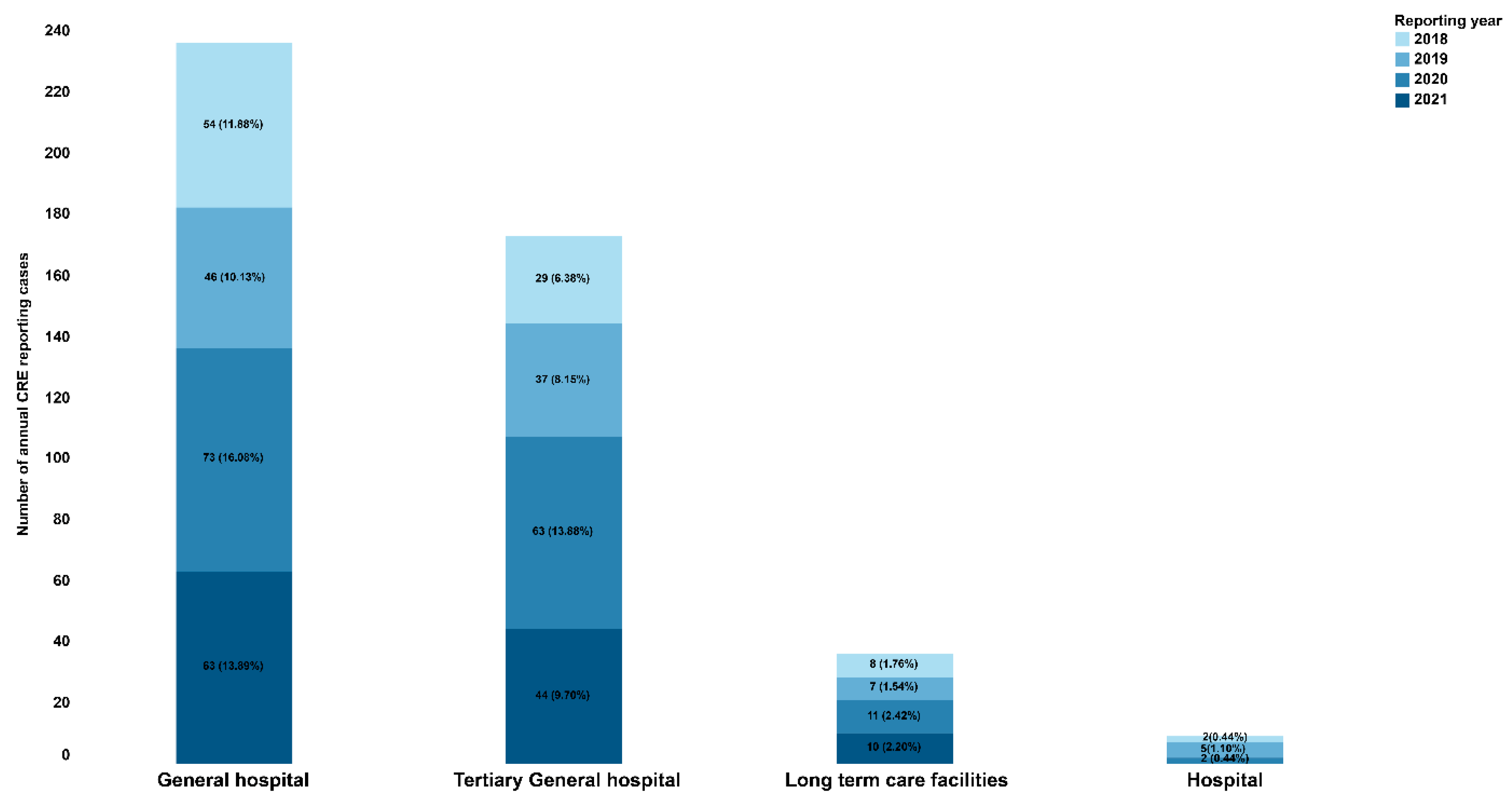

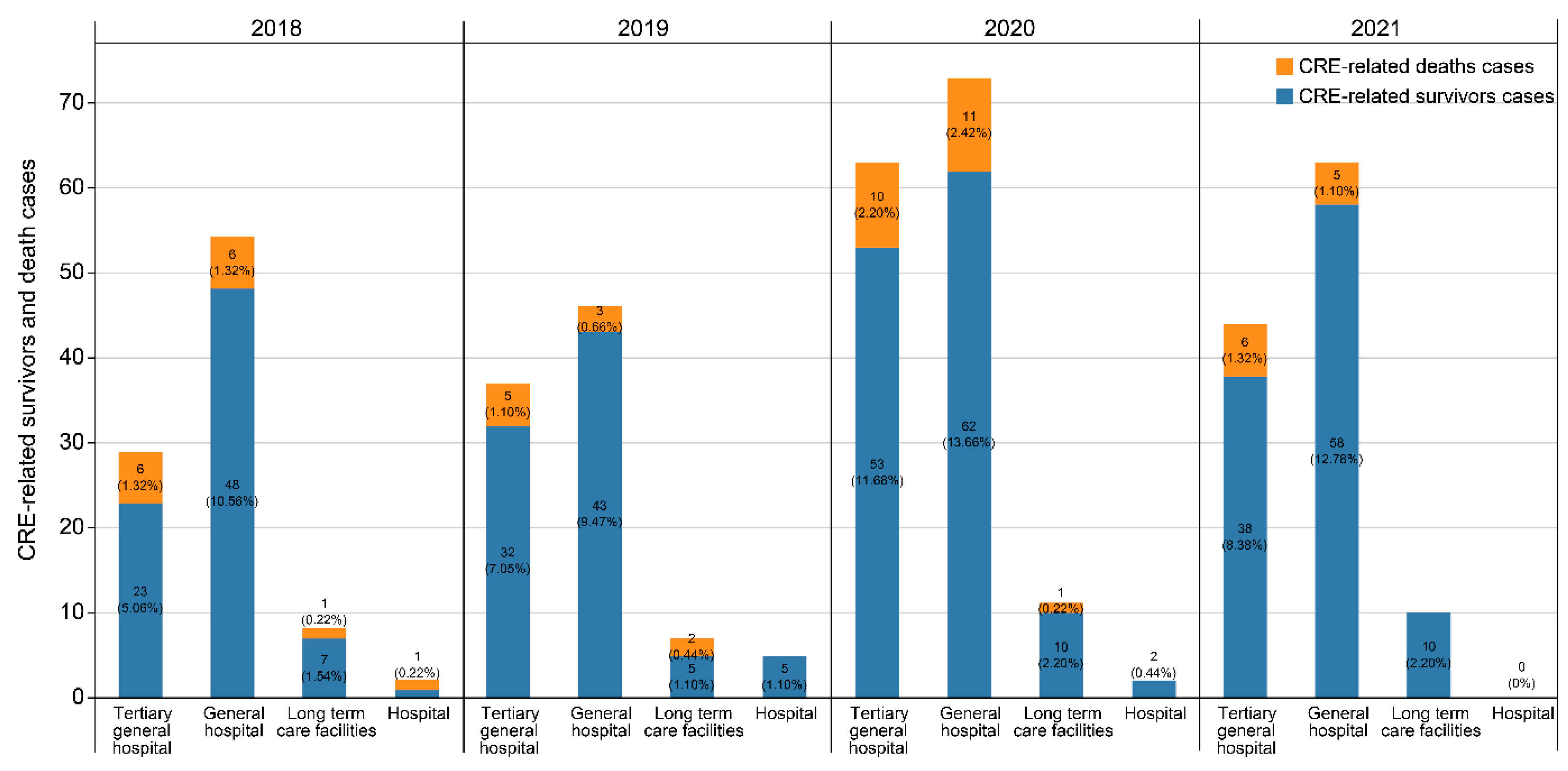

2. RESULTS

2.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

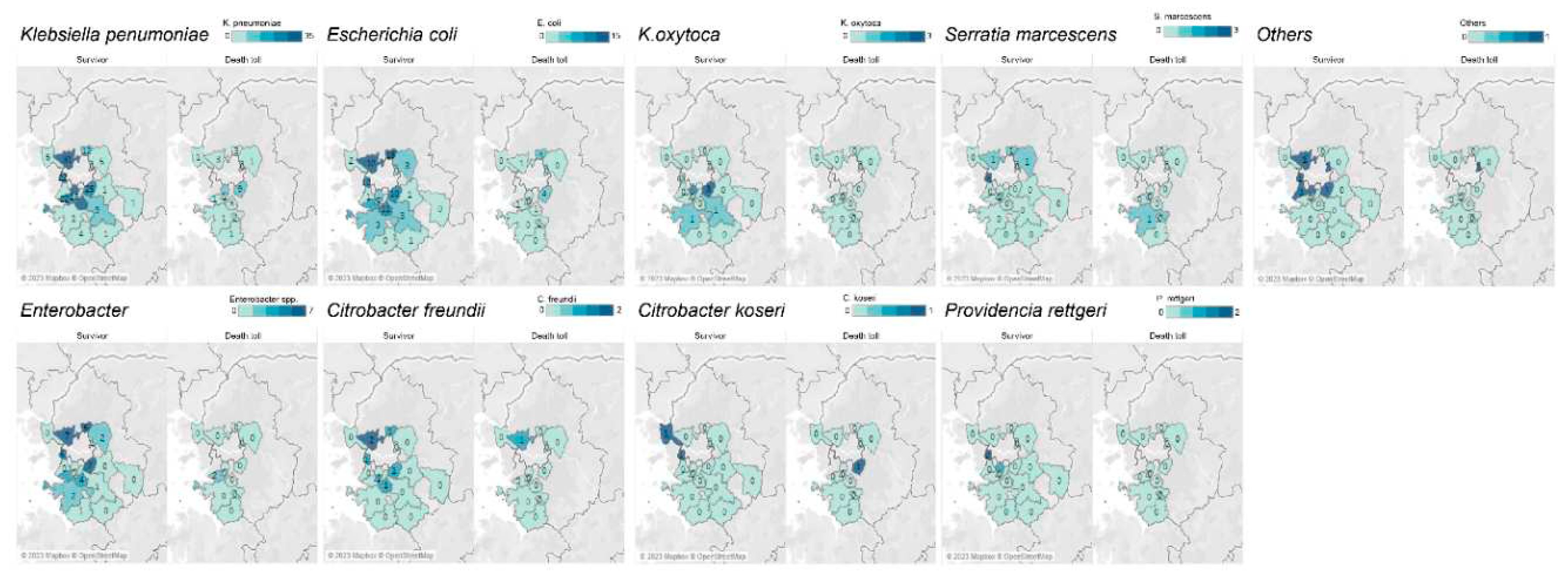

2.2. CRE occurrence distribution by strains and digestive enzymes

3. DISCUSSION

4. METHODS

4.1. Data collection

4.2. Statistical analysis

4.3. Definition of cases

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonomo, R.A.; Burd, E.M.; Conly, J.; Limbago, B.M.; Poirel, L.; Segre, J.A.; Westblade, L.F. Carbapenemase-producing Organisms: A Global Scourge. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, Research, and Development of New Antibiotics: The Who Priority List of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria and Tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.J.; Kim, M.K.; Shin, E.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoo, J.I. Molecular characteristic analysis and antimicrobial resistance of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) isolates in the Republic of Korea, 2017-2020. Weekly Health and Diseases 2021, 14, 3790–3804. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/filepath/boardDownload.es?bid=0031&list_no=718138&seq=1.

- Park, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.S.; Yu, J.K.; Han, S.H.; Kang, M.J.; Chae-Kyu, H.; Sang-Me, L.; Young-Hee, O. Prevalence of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Seoul, Korea. The Korean Society for Microbiology 2020, 50, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, E.B.; Ju, S.J.; Park, S.D.; Yoo, J.I.; Hwang, K.J. Distributions of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in Korea, 2018. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2019, 12, 1977–1983. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/filepath/boardDownload.es?bid=0031&list_no=711197&seq=1.

- Jeong, H.S.; Hyun, J.H. ; Lee,Y. K. Characteristics of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the Republic of Korea, 2021. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2022, 15, 2360–2363. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/filepath/boardDownload.es?bid=0031&list_no=720486&seq=1.

- Park, J.J.; Seo, Y.B.; Lee, J.; Eom, J.S.; Song, W.; Choi, Y.K.; Kim, S.R.; Son, H.J.; Cho, N.H. Positivity of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Patients Following Exposure Within Long-Term Care Facilities in Seoul, Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.W.; Park, S.S. Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (Cre) In a Long-Term Acute Care Facility in the Republic of Korea. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 27, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.J.; Kim, M.N.; Choi, S.H. Clearance of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (Cpe) Carriage: A Comparative Study of Ndm-1 and Kpc Cpe - Author’s Reply. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Choi, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Ryu, S.H.; Kim, S.K.; Hong, M.J.; Kwak, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, M.S.; Sung, H.; et al. Outbreak of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Associated With a Contaminated Water Dispenser and Sink Drains in the Cardiology Units of a Korean Hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Y. , Jean, S. S., Lee, Y. L., Lu, M. C., Ko, W. C., Liu, P. Y., & Hsueh, P. R. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Global and Narrative Review. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2021, 11, 601968. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facility Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) – November 2015 Update CRE Toolkit. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/cre/cre-guidance-508.pdf.

- Guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259462.

- Magiorakos, A. P. , Burns, K., Rodríguez Baño, J., Borg, M., Daikos, G., Dumpis, U.,... & Weber, J. T. Infection prevention and control measures and tools for the prevention of entry of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae into healthcare settings: guidance from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 2017, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomides, M. D. A. , Fontes, A. M. S., Silveira, A. O. S. M., Matoso, D. C., Ferreira, A. L., & Sadoyama, G. The importance of active surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) in colonization rates in critically ill patients. PloS one, 2022, 17, e0262554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz-Neiderman, A.; Braun, T.; Fallach, N.; Schwartz, D.; Carmeli, Y.; Schechner, V. Risk Factors for Carbapenemase-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (Cp-Cre) Acquisition Among Contacts of Newly Diagnosed Cp-Cre Patients. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.K.; Weinstein, R.A. The Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: The Impact and Evolution of a Global Menace. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S28–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Kim, K.H. Identification and Infection Control of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Intensive Care Units. Acute Critical Care 2021, 36, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Yi, J.; Ko, M.K.; Lee, S.O.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, K.H. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Acquisition in an Emergency Intensive Care Unit in a Tertiary Hospital in Korea: A Case-Control Study. J Korean Med Sci 2019, 34, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y. , Qin, Y., Liu, J., Li, Q., Dong, Y., Shang, Y., Huang, Y., & Liu, R. (2015). Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection/colonization and predictors of mortality: a retrospective study. Pathogens and global health, 109, 68–74. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.K.; Cho, S.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Park, S.H.; Choi, S.M.; Lee, D.G.; Choi, J.H.; Yoo, J.H. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Single Community-Based Hospital in Korea. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 48, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, M.; Sharma, S.; Poliansky Blash, S.; Patel, G.; Banach, D.B.; Phillips, M.; LaBombardi, V.; Anderson, K.F.; Kitchel, B.; Srinivasan, A.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Acquisition of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the Setting of Endemicity. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalia, M.; Kompoti, M.; Koutsikou, A.; Paridou, A.; Giannopoulou, P.; Trikka-Graphakos, E.; Clouva-Molyvdas, P. Diabetes Mellitus Is an Independent Risk Factor for ICU-Acquired Bloodstream Infections. Intensive Care Med. 2009, 35, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guh, A.Y.; Bulens, S.N.; Mu, Y.; Jacob, J.T.; Reno, J.; Scott, J.; Wilson, L.E.; Vaeth, E.; Lynfield, R.; Shaw, K.M.; et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in 7 US Communities, 2012-2013. JAMA. 2015, 314, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J-H. The Infinity War: How to Cope With Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2018, 33, e255. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Jin, L.; Gu, B.; Xie, L.; Yang, C.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections: Report From the China CRE Network. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01882–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suay-García, B.; Pérez-Gracia, M.T. Present and Future of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2019, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomo, R.A.; Burd, E.M.; Conly, J.; Limbago, B.M.; Poirel, L.; Segre, J.A.; Westblade, L.F. Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms: A Global Scourge. Clinical Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.M.; Mathema, B.; Larson, E.L. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the Community: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.G.; Bufalino, A.; Sturm, L.; Huang, R.H.; Ottenbacher, A.; Saake, K.; Winegar, A.; Fogel, R.; Cacchione, J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic, Central-Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI), and Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI): The Urgent Need to Refocus on Hardwiring Prevention Efforts. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, L.S.; Howard-Anderson, J.R.; Jacob, J.T.; Gottlieb, L.B. The Impact of COVID-19 on Multidrug-Resistant Organisms Causing Healthcare-Associated Infections: A Narrative Review. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, S.D.; Sickbert-Bennett,E. ; Moehring, R.; Cromer, A.; Lokhnygina, Y.; Dodds-Ashley, E.; Kalu, I.C.; DiBiase, L.; Weber, D.J.; Anderson, D.J.; CDC Prevention Epicenters Program. The Disproportionate Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on Healthcare-Associated Infections in Community Hospitals: Need for Expanding the Infectious Disease Workforce. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e34–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, C.E.; Coope, C.; Conway, L.; Higgins, J.P.; McCulloch, J.; Okoli, G.; Patel, B.C.; Oliver, I. Control of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Outbreaks in Acute Settings: An Evidence Review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 95, 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guideline for Healthcare-Associated Infection. North Chungcheong Province, South Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA); 2022. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20507020000&bid=0019.

| Survivor (n=397) | Death toll(n=57) | t or χ² | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender, Female (%) | 181 (45.6) | 22 (38.6) | 0.9867 | .3206 |

| Age, median, years (range) | 71 (0–96) | 72 (50-97) | 0.0382 | .5152 |

| Age group, years | ||||

| 0–9 | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 10–19 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 20–29 | 7 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 30–39 | 7 (1.8) | 3 (5.3) | ||

| 40–49 | 20 (5.0) | 5 (8.8) | ||

| 50–59 | 57 (14.4) | 9 (15.8) | ||

| 60–69 | 93 (23.4) | 11 (19.3) | ||

| 70–79 | 102 (25.7) | 12 (21.1) | ||

| 80–89 | 94 (23.7) | 12 (21.1) | ||

| 90–99 | 14 (3.5) | 5 (8.8) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Hospitalization | 366 (92.2) | 46 (80.7) | 7.8377 | .0051 |

| Intensive care unit history | 101 (25.4) | 15 (26.3) | ||

| Visit clinics | 18 (4.5) | 4 (7.0) | ||

| Healthcare facilities | ||||

| Tertiary General hospitals | 146 (36.8) | 27 (47.4) | ||

| General hospitals | 211 (53.1) | 25 (43.9) | ||

| Lone-term care facilities | 32 (8.1) | 4 (7.0) | ||

| Antibiotics * | ||||

| Yes | 161 (40.6) | 17 (29.8) | 0.9635 | .3263 |

| Carbapenems | 92 (46.9) | 14 (49.1) | ||

| Cephalosporins | 87 (53.1) | 6 (50.9) | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | 50 (35.5) | 5 (32.1) | ||

| Aminoglycosides | 38 (26.9) | 2 (7.1) | ||

| Glycopeptides | 43 (15.1) | 6 (14.3) | ||

| Other antibiotics | 54 (29.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Survivor(n=186) | Death toll(n=28) | t or χ² | P-value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying conditions N (%) N (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 66 (35.5) | 9 (32.1) | 0.119 | 0.730 | 0.257 (0.422–3.743) |

| Hypertension | 50 (26.9) | 2 (7.1) | 5.155 | 0.023 | 4.830 (1.045–22.328) |

| Brain stroke | 28 (15.1) | 4 (14.3) | 1 | 1.329 (0.373–4.738) | |

| Any malignancy | 54 (29.0) | 16 (57.1) | 8.737 | 0.003 | 0.425 (0.183–0.990) |

| Renal failure | 18 (9.7) | 3 (10.7) | 0.743 | 1.444 (0.290–7.177) | |

| Liver disease | 16 (8.6) | 3 (10.7) | 0.721 | 1.252 (0.280–5.590) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (2.2) | 1 (3.6) | 0.508 | 0.676 (0.052–8.795) | |

| Dialysis | 8 (4.3) | 3 (10.7) | 0.161 | 0.358 (0.055–2.319) | |

| Immunosuppressantadministration | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | - | |

| More than two underlying diseases | 61 (32.8) | 14 (50.0) | 3.164 | 0.075 | 0.440 (0.188–1.033) |

| Other diseases | 83 (44.6) | 11(39.3) | 0.282 | 0.596 | 1.039 (0.380–2.842) |

| Strain | Survivor (n=386) | Death toll (n=53) |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 230 (59.6) | 37 (69.8) |

| Escherichia coli | 89 (23.1) | 13 (24.5) |

| Enterobacter | 41 (10.6) | 2 (3.8) |

| Citrobacter freundii | 7 (1.8) | 1 (1.9) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 7 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serratia marcescens | 7 (1.8) | 1 (1.9) |

| Citrobacter koseri | 2 (0.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Providencia rettgeri | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiple strain | 11 (2.8) | 3 (5.7) |

| Others | 6 (1.6) | 1 (1.9) |

| Strain * | Survivor (n=212) | Death toll (n=29) |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| KPC | 151 (71.2) | 25 (86.2) |

| NDM | 49 (23.1) | 5 (17.2) |

| OXA | 11 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| VIM | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| IMP | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| GES | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).