Submitted:

02 July 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

- Evaluate the state of perceptions and opinions of people on AV functionality in different study contexts;

- 2)

- Identify the internal and external factors that condition people’s proclivity towards AVs and the functionality they provide; and

- 3)

- Specify research gaps in the existing literature and where opportunities exist for future research on willingness to adopt AVs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study approach

- 1)

- Whether the article/report is written in English;

- 2)

- Whether the study was conducted within the last five years; and

- 3)

- Whether the study has evaluated perceptions and opinions on AVs.

2.2. Attributes of reviewed articles and reports

3. Synopsis of the literature

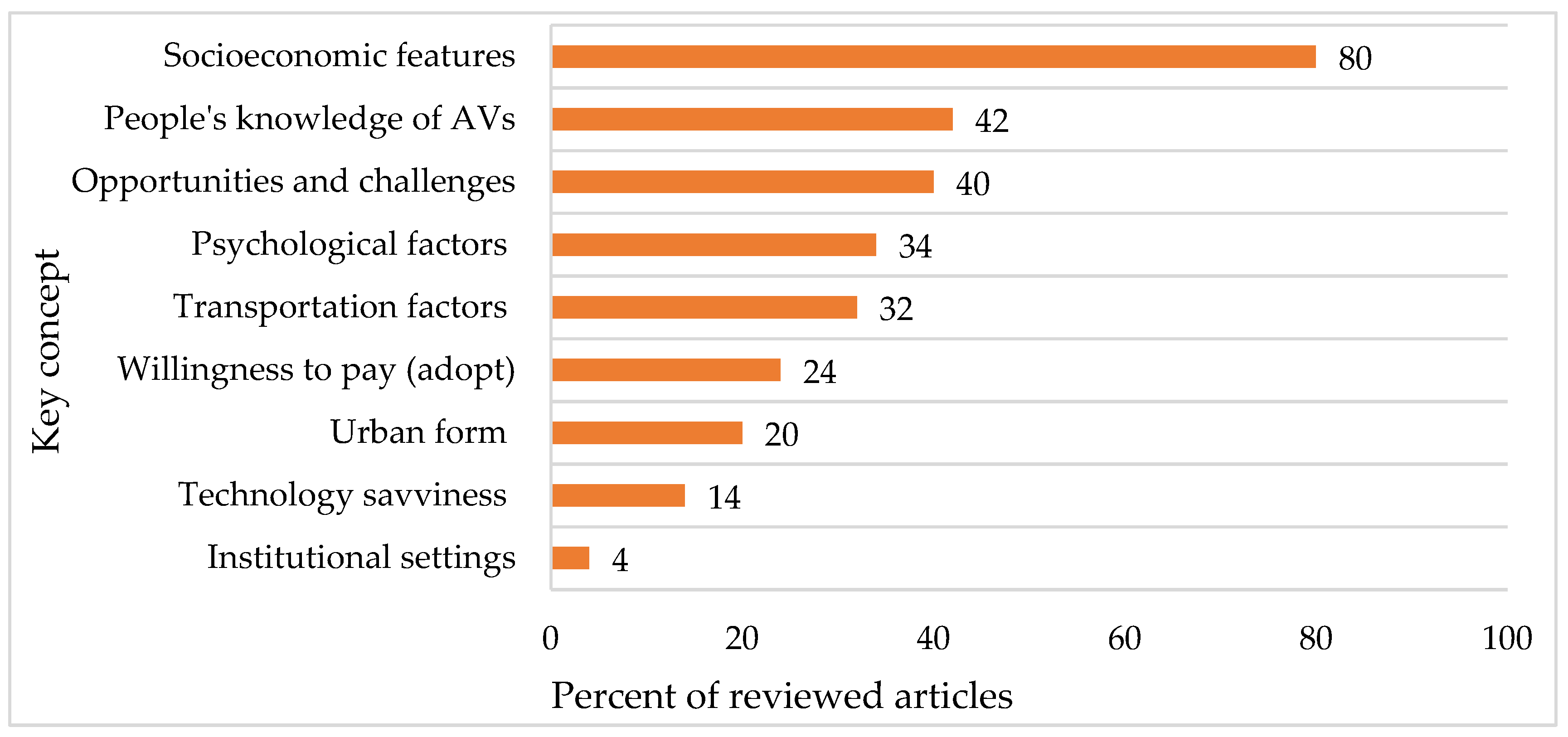

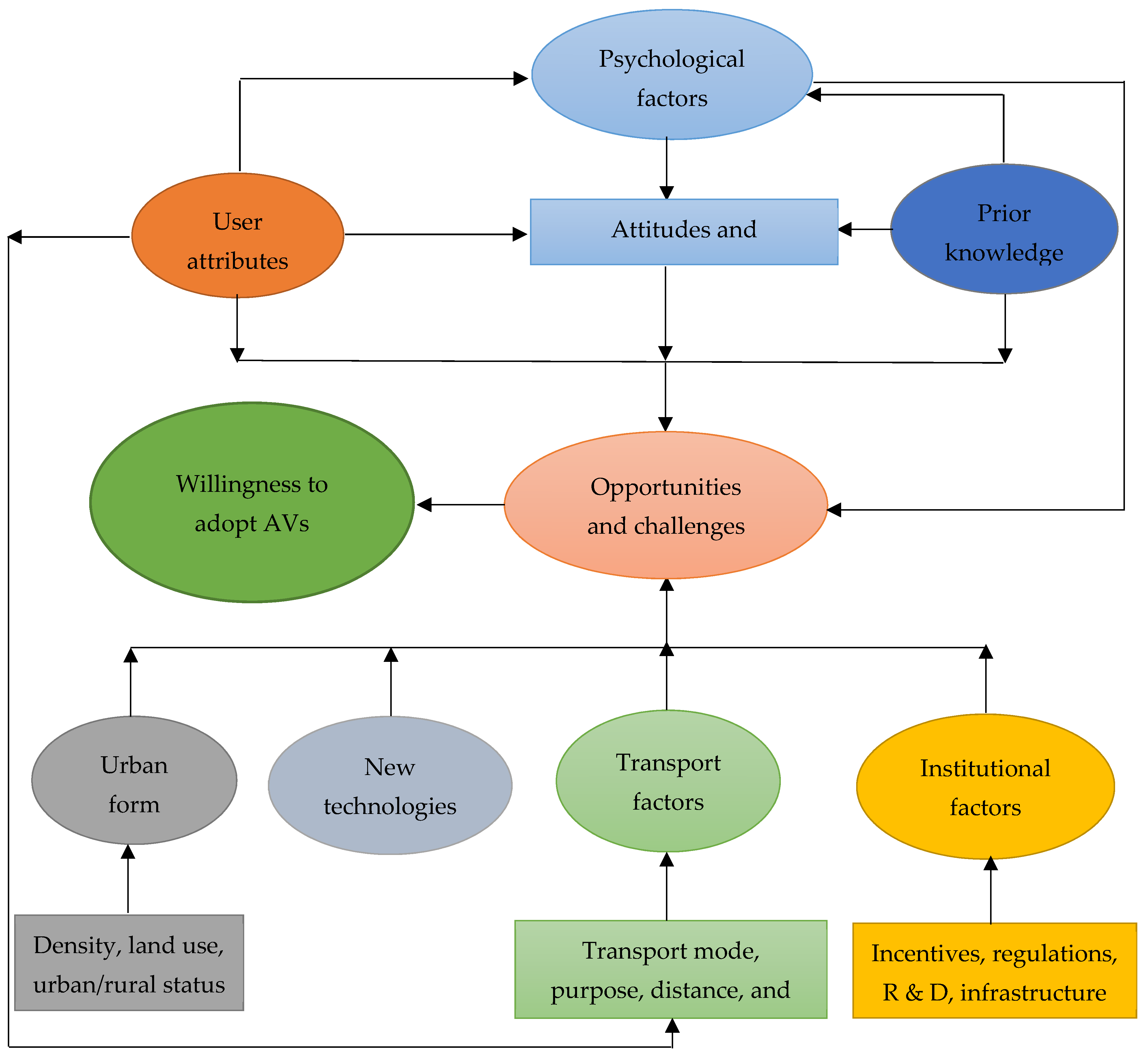

3.1. Contextualization of the factors of AV adoption

3.2. People’s willingness to use AVs and associated factors

3.3. Psychological factors of AV adoption

3.4. People’s attitudes and perceptions of AVs

3.5. Opportunities and challenges to adopting autonomous vehicles

3.6. People’s knowledge and experience of AVs

3.7. Socio-economic features

3.7.1. Age differentiation

3.7.2. Gender differentiation

3.7.3. Marital status

3.7.4. Educational attainment

3.7.5. Household income

3.7.6. Household size and composition

3.8. Transportation and travel factors

3.9. Impacts of the built environment on AV adoption

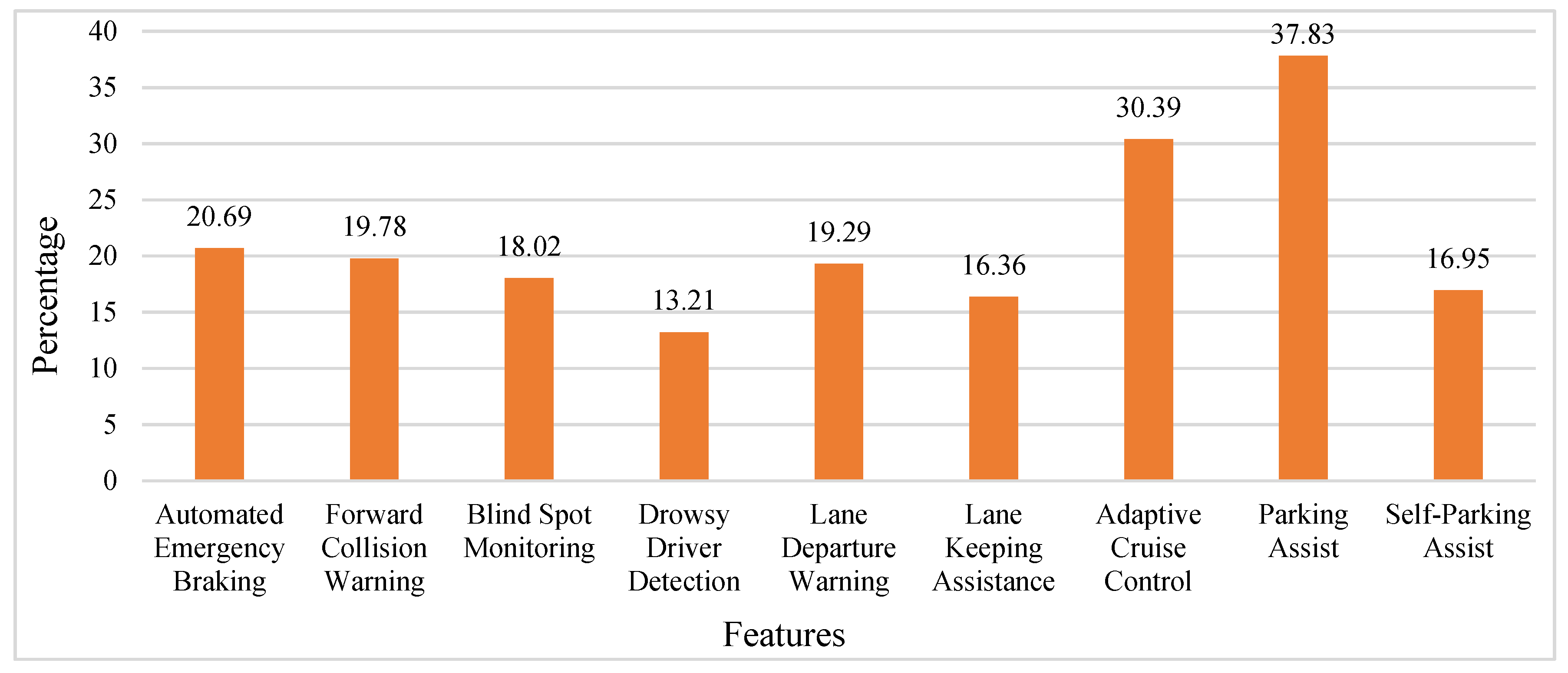

3.10. Impacts of cutting-edge technology on AV adoption and use

3.11. Impacts of institutional factors on AV adoption

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary

4.2. Policy recommendations

- 1)

- 2)

- Policy makers, manufacturers, and transport operators can arrange hands-on test drive opportunities for the people to engage and interact with the technology [88,89,90,91,92]. Thereby, it can increase public acceptance of AVs by enhancing the familiarity, trust, and effort expectancy of AVs and reducing misconceptions of safety barriers.

- 3)

- An efficient and transparent administration comprising officials from industry and government sectors can facilitate this inevitable transformation in the automotive industry by allocating subsidies for initial launching, for providing supporting environment, and for integrating with existing transport infrastructure and design [89,93,94]. By doing so, they can significantly increase AV adoption and use.

- 4)

- Concerned authorities can appoint an independent and certified tester to test maturity standards of AVs and AV producers and set some baseline standards to be maintained in order to achieve trust in AVs and increase their performance [92].

- 5)

- 6)

- Transportation engineers and designers should simplify the design and positioning of SAVs by providing clear video instructions, internet cafes, conference rooms, social networking place through engaging all people to make their journey fun and enjoyable [90,94]. Consequently, it can improve user experience and increase public acceptance and use of SAVs.

- 7)

- Auto manufacturers and interested stakeholders should invest more and strengthen research and development of this evolving technology to improve the reliability of the technology constantly and increase people’s trust to enhance public acceptance of AVs [90].

- 8)

- Practitioners should establish a set of comprehensive mitigation strategies such as limiting personal data acquisition, anonymize users’ identity before sharing data, strict regulatory framework in cyberspace to safeguard consumer data from cyber-attack, alleviate cyber worries. [95]. This can increase the acceptance and use of AVs by all cohorts of the society.

- 9)

- AV manufacturers should be accountable, ease users’ ethical concerns (e.g., privacy, cybersecurity, human rights), and prepare liability rules involving AVs, human drivers, and other road users before introducing AVs to the market [96]. This intervention can increase social welfare of AVs and thereby encourage people to adopt and use AVs.

4.3. Study limitations and directions for future research

- 1)

- Some studies selected samples from a specific stratum (e.g., higher educated people, experts, tech-savvy, visitors of pilot vehicles, geographically focused samples), thus overlooking large segments of the population. In short, data collectionmay reflect a self-selection bias and non-response bias under a controlled environment [57,61,67]. Thus, large, diverse, and representative segments of people should be included in the sample to obtain unbiased, true, and insightful results [34,46,66]. Doing so would enable reliable inference in a larger population, study diversity in human response to the innovation of autonomous mobility technologies, and be in a position to address disparities across population segments, particularly to the extent these disparities may be exacerbated by artificial intelligence (AI) and information technologies.

- 2)

- Psychological factors are often inadequately measured in studies [60,64,65],failing to capture their complete effects on the behavioral intentions to adopt AVs. Thus, it is recommended to include a more complete range of factors of human psychology to understand fully their effects on AVs adoption. Moreover, Given that AV technologies and the modalities of their deployment are still in flux and that the legal, infrastructural, and human factors are in the process of adjusting to the subtleties of immersion in a mobility context shaped by AI, researchers suggested to survey the same panel of respondents repeatedly over time to be in a position to trace trends in attitudes and perceptions based on their understanding from peers, relatives, and social and digital media, real-life experience of AVs, availability of cutting-edge technology, sense of personal risks, and changes in household locations (i.e., rural versus urban) [68]. This would also enable a more direct assessment of causal pathways and also deepen our understanding of socio-technological systems of designing and adopting AVs [100]. In turn, this would support the design of time-sensitive information sharing on the opportunities presented by AVs and better policies on AV deployment that mitigate risks, uncertainties, and disparities.

- 3)

- By keeping the questionnaire and other survey instruments short and simple, a number of important questions were omitted (also reflected in Figure 2) that could significantly shed light on people’s perceptions. Thus, the effects on willingness to adopt and willingness to pay should be investigated considering different costs, urban form, traffic scenarios, technological advancement and uncertainty in technology, and institutional settings [64,67,101]. Moreover, productivity, efficiency, and all types of impacts of AVs should be considered to estimate consumer’s psychology and intentions to adopt AVs [18,67].

- 4)

- As full-scale AVs are not yet commercially available to people, most studies collected data based on the imaginary of travelers, assuming hypothetical driving and urban setting (i.e., a typical road segment, same speed, homogeneous traffic scenario), and educating respondents about AVs beforehand, which may be at variance from the real-world scenario and could influence perceptions [26,70,102]. Moreover, some studies also generated synthetic data using driving simulators where participants just sit behind the wheel without doing any direct maneuver, which does not capture a real representation of the population [34,49,65].Thus, further studies should consider mixed methods integrating simulation and statistical analysis and relevant user-behavior data reflecting real-world urban environment and traffic scenarios (e.g., mixed traffic) which can provide a higher level of accuracy in assessing perceptions and opinions of people on AVs [43,61,103].

- 5)

- Major legal and ethical aspects (e.g., requirement of driving license, responsibility for crashes involving AVs, whether to sacrifice one to save more, fair access to AV services for all, etc.) are largely unexplored in the extant literature which could affect implementation of AVs [100,104,105]. Thus, future studies should investigate different legal and ethical values in socio-political, spatial, environmental, and technological dimensions to facilitate future AV adoption.

- 6)

- Given the number of existing studies on AVs and the conflicting nature of results of some of these studies, a systematic econometric meta-analysis would highlight the consistencies embedded in this body of literature so as to generalize the results of individual studies and tailor more robust public policies and business practices for the successful deployment of AVs. Furthermore, most analytic approaches used to study data on willingness to adopt AVs are econometric and share stiff distributional and linearity requirement. Given the complexity of the topic of study, it is our contention that empirical studies using machine learning and deep learning based techniques would enhance our ability to understand the complex relationship between different internal and external factors operating at multiple levels and the AV adoption tendency of people.

- 7)

- As discussed in Table 1, an increasing number of studies are conducted in the developed countries, where government, auto industries, and concerned private stakeholders are financing for testing and implementing AVs. However, AVs and SAVs are relatively new concepts in developing countries and information on people’s perceptions and opinions on AVs and the factors that influence people’s BI towards AVs are unavailable [97,98]. People’s perceptions, attitudes and determinants of AVs would be different in developing countries compared to developed countries due to differences in their socioeconomic status, cultures, and attitudes [98]. Thus, research should be conducted to understand people’s perceptions and internal and external factors of AVs in developing contexts.

- 8)

- Considering the deep ripple effects of the recent health crises due to the COVID-19 pandemic on human mobility [106,107,108,109,110], future research should investigate how this pandemic may shift perceptions and opinions of people to share AVs with others amidst the fear of disease transmission and how a more resilient transportation and mobility system can be fostered. Although electrification and automation of vehicles have the potential to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions, some researchers are skeptical about the net energy and emission effects of vehicles automation due to increased travel demand [6]. Thus, future studies should investigate how these potential health effects may change the perception and motivation of people to use these technologies.

5. Conclusions

Credit authorship contribution statement

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Declarations of interest

References

- Castritius, S.-M., et al., Public acceptance of semi-automated truck platoon driving. A comparison between Germany and California. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 74: p. 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. and K.M. Kockelman, Are we ready to embrace connected and self-driving vehicles? A case study of Texans. Transportation, 2018. 45(2): p. 641-675. [CrossRef]

- Gruel, W. and J.M. Stanford, Assessing the Long-term Effects of Autonomous Vehicles: A Speculative Approach. Transportation Research Procedia, 2016. 13: p. 18-29. [CrossRef]

- Wali, B. and A.J. Khattak, A joint behavioral choice model for adoption of automated vehicle ride sourcing and carsharing technologies: Role of built environment & sustainable travel behaviors. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2022. 136. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., et al., Shared use of electric autonomous vehicles: Air quality and health impacts of future mobility in the United States. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2021. 149. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. and H. Yang, Low carbon future of vehicle sharing, automation, and electrification: A review of modeling mobility behavior and demand. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2023. 177. [CrossRef]

- Compostella, J., et al., Near-(2020) and long-term (2030–2035) costs of automated, electrified, and shared mobility in the United States. Transport Policy, 2020. 85: p. 54-66. [CrossRef]

- Daziano, R.A., M. Sarrias, and B. Leard, Are consumers willing to pay to let cars drive for them? Analyzing response to autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2017. 78: p. 150-164. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M. and J.-C. Thill, Impacts of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles on Urban Transportation and Environment: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2023. 96. [CrossRef]

- Cyganski, R., et al., Simulation of automated transport offers for the city of Brunswick. Procedia Computer Science, 2018. 130: p. 872-879. [CrossRef]

- Penmetsa, P., et al., Perceptions and expectations of autonomous vehicles–A snapshot of vulnerable road user opinion. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2019. 143: p. 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. and D. Dai. Public perceptions of self-driving cars: The case of Berkeley, California. in Transportation Research Board 93rd Annual Meeting. 2014. Washington, DC, USA: Transportation Research Board.

- Van den Berg, V.A. and E.T. Verhoef, Autonomous cars and dynamic bottleneck congestion: The effects on capacity, value of time and preference heterogeneity. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 2016. 94: p. 43-60. [CrossRef]

- Kopelias, P., et al., Connected & autonomous vehicles–Environmental impacts–A review. Science of The Total Environment, 2020. 712: p. 135237. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S., E. Chaniotakis, and C. Antoniou, Shared autonomous vehicle services: A comprehensive review. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2020. 111: p. 255-293. [CrossRef]

- SAE International, Taxonomy and definitions for terms related to on-road motor vehicle automated driving systems. 2018, SAE International Warrendale, Pa.

- Schoettle, B. and M. Sivak, A survey of public opinion about autonomous and self-driving vehicles in the US, the UK, and Australia. 2014, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Transportation Research Institute: Ann Arbor, Michigan.

- Sparrow, R. and M. Howard, When human beings are like drunk robots: Driverless vehicles, ethics, and the future of transport. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2017. 80: p. 206-215. [CrossRef]

- Tafidis, P., et al., Safety implications of higher levels of automated vehicles: a scoping review. Transport Reviews, 2021: p. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Soteropoulos, A., M. Berger, and F. Ciari, Impacts of automated vehicles on travel behaviour and land use: an international review of modelling studies. Transport reviews, 2019. 39(1): p. 29-49. [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J., Incumbent-led transitions and civil society: Autonomous vehicle policy and consumer organizations in the United States. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2020. 151: p. 119825. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T. and C. Cavoli, Automated vehicles: Exploring possible consequences of government (non) intervention for congestion and accessibility. Transport Reviews, 2019. 39(1): p. 129-151. [CrossRef]

- Van Brummelen, J., et al., Autonomous vehicle perception: The technology of today and tomorrow. Transportation research part C: emerging technologies, 2018. 89: p. 384-406. [CrossRef]

- Hilgarter, K. and P. Granig, Public perception of autonomous vehicles: a qualitative study based on interviews after riding an autonomous shuttle. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 72: p. 226-243. [CrossRef]

- Gurumurthy, K.M. and K.M. Kockelman, Modeling Americans’ autonomous vehicle preferences: A focus on dynamic ride-sharing, privacy & long-distance mode choices. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2020. 150.

- Clark, J.R., N.A. Stanton, and K.M. Revell, Directability, eye-gaze, and the usage of visual displays during an automated vehicle handover task. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2019. 67: p. 29-42. [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S., et al., A multi-level model on automated vehicle acceptance (MAVA): A review-based study. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 2019. 20(6): p. 682-710. [CrossRef]

- Jing, P., et al., The determinants behind the acceptance of autonomous vehicles: A systematic review. Sustainability, 2020. 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., State-of-the-art of factors affecting the adoption of automated vehicles. Sustainability, 2022. 14(11). [CrossRef]

- Gkartzonikas, C. and K. Gkritza, What have we learned? A review of stated preference and choice studies on autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2019. 98: p. 323-337. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.S., et al., Public Acceptance towards Emerging Autonomous Vehicle Technology: A Bibliometric Research. Sustainability, 2023. 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.J., N. Tada, and S. Managi, Consumer demand for fully automated driving technology. Economic Analysis and Policy, 2019. 61: p. 16-28. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I. and G. Dimitrakopoulos, An empirical investigation on consumers’ intentions towards autonomous driving. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2018. 95: p. 773-784. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., et al., What drives people to accept automated vehicles? Findings from a field experiment. Transportation research part C: Emerging Technologies, 2018. 95: p. 320-334. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M., et al., Assessing the utility of TAM, TPB, and UTAUT for advanced driver assistance systems. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 2017. 108: p. 361-373. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P., K.M. Kockelman, and A. Singh, Assessing public opinions of and interest in new vehicle technologies: An Austin perspective. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2016. 67: p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M., R. Happee, and J.C. de Winter, Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2015. 32: p. 127-140. [CrossRef]

- Schoettle, B. and M. Sivak, Public opinion about self-driving vehicles in China, India, Japan, the US, the UK, and Australia. 2014, Transportation Research Institute, The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, Michigan.

- Underwood, S. and D. Firmin, Automated vehicles forecast: vehicle symposium opinion survey. 2014.

- Begg, D., A 2050 Vision for London: What are the implications of driverless transport? 2014, Clear Channel: London, United Kingdom.

- Bazilinskyy, P., M. Kyriakidis, and J. de Winter, An international crowdsourcing study into people’s statements on fully automated driving. Procedia Manufacturing, 2015. 3: p. 2534-2542. [CrossRef]

- Piao, J., et al., Public views towards implementation of automated vehicles in urban areas. Transportation Research Procedia, 2016. 14: p. 2168-2177. [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.O., Passenger’s subjective traffic safety, in-vehicle security and emergency management in the driverless shuttle bus in Finland. Transport Policy, 2018. 61: p. 106-110. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J., et al., Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for advanced vehicle technology options and fuel types. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2015. 60: p. 511-524. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R., T.H. Rashidi, and J.M. Rose, Preferences for shared autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2016. 69: p. 343-355. [CrossRef]

- Haboucha, C.J., R. Ishaq, and Y. Shiftan, User preferences regarding autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2017. 78: p. 37-49. [CrossRef]

- König, M. and L. Neumayr, Users’ resistance towards radical innovations: The case of the self-driving car. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2017. 44: p. 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, F., M. Noruzoliaee, and A. Mohammadian, Shared versus private mobility: Modeling public interest in autonomous vehicles accounting for latent attitudes. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2018. 97: p. 456-477. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., S. Guhathakurta, and E.B. Khalil, The impact of private autonomous vehicles on vehicle ownership and unoccupied VMT generation. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2018. 90: p. 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Talebian, A. and S. Mishra, Predicting the adoption of connected autonomous vehicles: A new approach based on the theory of diffusion of innovations. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2018. 95: p. 363-380. [CrossRef]

- Kapser, S. and M. Abdelrahman, Acceptance of autonomous delivery vehicles for last-mile delivery in Germany–Extending UTAUT2 with risk perceptions. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2020. 111: p. 210-225. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., et al., Automated vehicle acceptance in China: Social influence and initial trust are key determinants. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2020. 112: p. 220-233. [CrossRef]

- Wadud, Z. and F.Y. Huda, Fully automated vehicles: the use of travel time and its association with intention to use. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Transport, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, K., M. Sweet, and T. Olsen, Forecasting the outlook for automated vehicles in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area using a 2016 consumer survey. Retrieved on September, 2018. 3: p. 2018.

- Bansal, P. and K.M. Kockelman, Forecasting Americans’ long-term adoption of connected and autonomous vehicle technologies. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2017. 95: p. 49-63. [CrossRef]

- Webb, J., C. Wilson, and T. Kularatne, Will people accept shared autonomous electric vehicles? A survey before and after receipt of the costs and benefits. Economic Analysis and Policy, 2019. 61: p. 118-135. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K. and G. Rampersad, Trust in driverless cars: Investigating key factors influencing the adoption of driverless cars. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 2018. 48: p. 87-96. [CrossRef]

- Hulse, L.M., H. Xie, and E.R. Galea, Perceptions of autonomous vehicles: Relationships with road users, risk, gender and age. Safety Science, 2018. 102: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kaye, S.-A., et al., Assessing the feasibility of the theory of planned behaviour in predicting drivers’ intentions to operate conditional and full automated vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 74: p. 173-183. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. and C.-K. Fan, Autonomous vehicles, risk perceptions and insurance demand: An individual survey in China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2019. 124: p. 549-556. [CrossRef]

- Faas, S.M., L.-A. Mathis, and M. Baumann, External HMI for self-driving vehicles: which information shall be displayed? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 68: p. 171-186. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A., G. Azimi, and X. Jin, Examining human attitudes toward shared mobility options and autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 72: p. 133-154. [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S., et al., Using the UTAUT2 model to explain public acceptance of conditionally automated (L3) cars: A questionnaire study among 9,118 car drivers from eight European countries. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 74: p. 280-297. [CrossRef]

- Hagl, M. and D.R. Kouabenan, Safe on the road–Does Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems Use affect Road Risk Perception? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 73: p. 488-498. [CrossRef]

- Ha, T., et al., Effects of explanation types and perceived risk on trust in autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 73: p. 271-280. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., This is not me! Technology-identity concerns in consumers’ acceptance of autonomous vehicle technology. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 74: p. 345-360. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G., Y. Chen, and J. Zheng, Modelling the acceptance of fully autonomous vehicles: A media-based perception and adoption model. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 73: p. 80-91. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., Attitudes towards privately-owned and shared autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2020. 72: p. 297-306. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F., Factors affecting the decision to use autonomous shuttle services: Evidence from a scooter-dominant urban context. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2019. 67: p. 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F., et al., The determinants of public acceptance of autonomous vehicles: An innovation diffusion perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Feys, M., E. Rombaut, and L. Vanhaverbeke, Experience and Acceptance of Autonomous Shuttles in the Brussels Capital Region. Sustainability, 2020. 12(20). [CrossRef]

- Zmud, J.P. and I.N. Sener, Towards an understanding of the travel behavior impact of autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Procedia, 2017. 25: p. 2500-2519. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. 1985: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Fisbein, M. and I. Ajzen, Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. 1975, Reading, Massachusetts, US: Addison-Wiley Publishing Company.

- Davis, F.D., A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results, in Sloan School of Management. 1985, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Xie, H., et al., The formation of initial trust by potential passengers of self-driving taxis. Journal of Decision Systems, 2022: p. 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Bakioglu, G., et al., Examination of the role of safety concerns from autonomous vehicle ownership choice: results of a stated choice experiment in Istanbul, Turkey. Transportation Letters, 2022. 14(10): p. 1172-1183. [CrossRef]

- Rejali, S., et al., Comparison of technology acceptance model, theory of planned behavior, and unified theory of acceptance and use of technology to assess a priori acceptance of fully automated vehicles. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2023. 168. [CrossRef]

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., et al., Modeling users’ adoption of shared autonomous vehicles employing actual ridership experiences. Transportation Research Record, 2022. 2676(11): p. 462-478. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R., T.H. Rashidi, and V.V. Dixit, Autonomous driving and residential location preferences: Evidence from a stated choice survey. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2019. 108: p. 255-268. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. and K.G. Goulias, Perceived usefulness and intentions to adopt autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2022. 161: p. 170-185. [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, K., M. Sweet, and T. Olsen, Forecasting the outlook for automated vehicles in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area using a 2016 consumer survey. Ryesron School of Urban and Regional Planning, 2018.

- Alsghan, I., et al., The determinants of consumer acceptance of autonomous vehicles: A case study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 2022. 38(14): p. 1375-1387. [CrossRef]

- National Science Foundation. Report shows United States leads in science and technology as China rapidly advances. 2018 [cited 2021 4/15/2021]; Available from: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180124113951.htm.

- Gironés, E.S., R. van Est, and G. Verbong, The role of policy entrepreneurs in defining directions of innovation policy: A case study of automated driving in the Netherlands. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2020. 161: p. 120243. [CrossRef]

- Schippl, J., B. Truffer, and T. Fleischer, Potential impacts of institutional dynamics on the development of automated vehicles: Towards sustainable mobility? Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 2022. 14: p. 100587. [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.J., et al., Policy Implications of Emerging Vehicle and Infrastructure Technology. 2014, Center for Transportation Research, The University of Texas at Austin.

- Acharya, S. and M. Mekker, Public acceptance of connected vehicles: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 2022. 88: p. 54-68. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., S. Polunsky, and S. Jones, Chapter 8 - Transportation policies for connected and automated mobility in smart cities, in Smart Cities Policies and Financing, J. R.Vacca, Editor. 2022, Elsevier. p. 97-116. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L., K.F. Yuen, and X. Wang, Explore public acceptance of autonomous buses: An integrated model of UTAUT, TTF and trust. Travel Behaviour and Society, 2023. 31: p. 120-130. [CrossRef]

- Camps-Aragó, P., et al., Encouraging the sustainable adoption of autonomous vehicles for public transport in Belgium: citizen acceptance, business models, and policy aspects. Sustainability, 2022. 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B., et al., Determinants of intention to use autonomous vehicles: Findings from PLS-SEM and ANFIS. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 2023. 70. [CrossRef]

- Ljubi, K. and A. Groznik, Role played by social factors and privacy concerns in autonomous vehicle adoption. Transport Policy, 2023. 132: p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F., et al., A theoretical investigation of user acceptance of autonomous public transport. Transportation, 2022: p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.K., et al., A multinational empirical study of perceived cyber barriers to automated vehicles deployment. Scientific Reports, 2023. 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Qian, L., et al., The role of values and ethics in influencing consumers’ intention to use autonomous vehicle hailing services. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2023. 188. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, P. and M. Lukovics, Factors influencing public acceptance of self-driving vehicles in a post-socialist environment: Statistical modelling in Hungary. Regional Statistics, 2022. 12(2): p. 149-176. [CrossRef]

- Farzin, I., A.R. Mamdoohi, and F. Ciari, Autonomous Vehicles Acceptance: A Perceived Risk Extension of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology and Diffusion of Innovation, Evidence from Tehran, Iran. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 2022: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Modliński, A., E. Gwiaździński, and M. Karpińska-Krakowiak, The effects of religiosity and gender on attitudes and trust toward autonomous vehicles. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 2022. 33(1). [CrossRef]

- Thurner, T., K. Fursov, and A. Nefedova, Early adopters of new transportation technologies: Attitudes of Russia’s population towards car sharing, the electric car and autonomous driving. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2022. 155: p. 403-417. [CrossRef]

- Maeng, K. and Y. Cho, Who will want to use shared autonomous vehicle service and how much? A consumer experiment in South Korea. Travel Behaviour and Society, 2022. 26: p. 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S. and M.R. Fatmi, Modelling the adoption of autonomous vehicle: How historical experience inform the future preference. Travel Behaviour and Society, 2022. 26: p. 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., et al., Sharing the roads: Robot drivers (vs. human drivers) might provoke greater driving anger when they perform identical annoying driving behaviors. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 2022. 38(4): p. 309-323. [CrossRef]

- Soh, E. and K. Martens, Value dimensions of autonomous vehicle implementation through the Ethical Delphi. Cities, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wexler, N. and Y. Fan, Gauging Public Attitudes and Preferences Toward a Hypothetical Future Public Shared Automated Vehicle System: Examining the Roles of Gender, Race, Income, and Health. Transportation Research Record, 2022: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., J.-C. Thill, and K.C. Paul, COVID-19 pandemic severity, lockdown regimes, and people’s mobility: Early evidence from 88 countries. Sustainability, 2020. 12(21). [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M., et al., Machine Learning on the COVID-19 Pandemic, Human Mobility and Air Quality: A Review. IEEE Access, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.F., et al., Risk attitudes and human mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., et al., A big-data driven approach to analyzing and modeling human mobility trend under non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19 pandemic. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2021. 124: p. 102955. [CrossRef]

- Bhouri, M.A., et al., COVID-19 dynamics across the US: A deep learning study of human mobility and social behavior. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2021. 382. [CrossRef]

| Author | Study area | Data source | Sample size | Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | Athens, Greece | Online survey | 483 | SEM, FA |

| [34] | Xi’an, China | Participants in a field test | 300 | SEM, FA, MLR |

| [35] | Boston, MA | Participants in driving simulator, online survey | 430 | SEM, FA, MLR |

| [36] | Austin, USA | Online survey | 347 | OPM, SUM |

| [37] | 109 countries | Online survey | 4886 | DS |

| [17] | US, UK, and Australia | Online survey | 1533 | DS, ANOVA |

| [38] | China, India, and Japan | Online survey | 1722 | DS, ANOVA |

| [39] | Expert around the world | Expert opinions from AV Symposium, 2014 | 217 | DS |

| [12] | Berkeley, California | Opinion of museum visitors | 107 | MNL, LLM |

| [40] | London, UK | Survey of transport professionals | 3500 | DS |

| [41] | 112 countries of the world | Online survey | 8862 | DS |

| [42] | La Rochelle, France | Online and phone survey | 425 | DS |

| [43] | Vantaa, Finland | Participants with experience of driverless shuttle | 197 | DS, ANOVA |

| [44] | Six cities in South Korea | Stated preference survey | 633 | MDCP, MNP |

| [45] | Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney | Stated preference survey | 435 | MLM |

| [46] | Israel and North America | Stated preference survey | 721 | LKM, FA |

| [8] | USA | Online survey | 1260 | CLM, PRPLM, SRPLM |

| [47] | 33 countries | Online survey | 489 | DS |

| [48] | Washington, USA | Travel survey | 2726 | OPM, SEM |

| [49] | Atlanta, USA | Travel survey | 10278 | LRM, MIP |

| [50] | Memphis, USA | Questionnaire survey | 327 | DS |

| [51] | Germany | Online survey | 501 | SEM |

| [52] | China | Questionnaire survey | 647 | SEM |

| [25] | USA | Online survey | 2588 | MNL |

| [32] | Japan | Online survey | 246642 | MLR, OLR |

| [53] | Bangladesh | Online survey | 621 | MLR |

| [54] | Toronto and Hamilton Area, Canada | Online survey | 3201 | PM |

| [55] | USA | Online survey | 2167 | BLM, WMNL |

| [56] | Brisbane, Australia | Household survey | 447 | MNL |

| [2] | Texas, USA | Online survey | 1088 | OPM |

| [57] | Adelaide, Australia | Online survey | 101 | FA |

| [58] | UK | Online survey | 916 | MNL |

| [59] | Australia | Online survey | 505 | MLR |

| [60] | China | Online survey | 1164 | DS, ANOVA |

| [26] | UK | Experimental study | 30 | ANOVA, PC |

| [61] | Germany | Experimental study | 59 | ANOVA, HLM |

| [62] | US | Stated preference survey | 1390 | SEM |

| [24] | Austria | Face-to-face interviews | 19 | DS, qualitative analysis |

| [1] | Germany and California | Online survey | 536 | FA, SEM, LRM |

| [11] | Pennsylvania, USA | General public survey | 798 | DS |

| [63] | Eight European countries | Online survey | 9118 | FA, SEM |

| [64] | Germany | Experimental study | 101 | DS, FA, ANOVA |

| [65] | Korea | Experimental study | 48 | DS, FA, ANOVA, MLR |

| [66] | Singapore | Face-to-face interviews | 353 | FA, SEM |

| [67] | Beijing, China | Face-to-face interviews | 355 | FA, SEM |

| [68] | USA | Online survey | 721 | FA, MNL |

| [69] | Taiwan | Face-to-face interviews | 700 | FA, SEM, ANOVA |

| [70] | Seoul, Republic of Korea | Online survey | 526 | FA, SEM |

| [71] | Brussels, Belgium | Online survey | 529 | DS, HLM |

| [72] | Austin, TX, USA | Online survey | 556 | DS |

| Study | Positive factors | Negative factors |

|---|---|---|

| [36] | Social acceptance, reliability, high income, tech savvy, presence of children, driving alone, urban living, higher VMT, long commute. | Holding a driver’s license, living in job-dense areas, being elderly, familiarity with carsharing and ridesharing. |

| [2] | Familiarity with Google car, being supportive of government intervention, high income, higher VMT, experienced fatal crashes, digital connectivity. | Holding a driver’s license, being elderly, living in dense area, living far away from transit stations, familiarity with ride-sourcing services. |

| [37] | Higher VMT, experience with automatic cruise control feature, male, higher income. | - |

| [44] | Cutting edge AV features. | High purchase price, concerned about safety. |

| [25] | Long-distance business travel, high income, college educated, employment density. | Higher travel time, elderly, presence of a worker in household, holding driver’s license, population density. |

| [32] | Male, travel assistance for elderly, high income, children in household, car ownership, availability of AV features. | Higher purchase and maintenance cost, information leakage to third parties, long travel time, driving on local roads, holding a driver’s license. |

| [54] | High income, male, possession of a smartphone, employment density, familiarity with and user of shared mobility. | Unaware of Google car. |

| [56] | High income, environmentally aware, open to public transport and ride-sharing options. | - |

| [55] | Long travel distance, experienced with automated features. | - |

| Studies | PU | PT | PEU | SI | TS | PR | PBC | TA | PS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | |||||

| [34] | 0.43 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.14 | |||||

| [35] | 0.80 | 0.13 | 0.10 | ||||||

| [52] | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.10 | |||||

| [51] | 0.23 | -0.05 | 0.17 | -0.17 | -0.28 | ||||

| [1] | 0.49 | 0.29 | |||||||

| [63] | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.40 | ||||||

| [67] | 0.42 | -0.11 | |||||||

| [69] | 0.35 | 0.04 | |||||||

| [70] | 0.45 | 0.47 | |||||||

| [59] | 0.64 | 0.30 | -0.05 | ||||||

| [35] | 0.29 | 0.05 | -0.05 | ||||||

| [69] | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.43 | ||||||

| [52] | 0.20 | 0.10 | |||||||

| [58] | -0.24 | ||||||||

| [66] | -0.11 | ||||||||

| [67] | 0.42 | 0.09 | -0.11 |

| Author | Opportunities (%) | Challenges (%) |

|---|---|---|

| [33] | Solution to many problems (88%), easy to operate (64%), clear and understandable interaction (69%), easy to become skillful (66%), useful to meet driving needs (46%), safe travel (44%), interesting travel (38.3%), low crashes (55.3%) | Safety concern (55%), waste of time (65.6%), make life more complicated (58.8%), do not increase social status (33%) |

| [36] | Reduction in crashes (63%), talk or text to others (75%), surf the internet 36%), email while driving (45.2%) | Interactions with conventional vehicles (48%), affordability (38%), equipment or system failure (50%) |

| [17] | Fuel economy (72%), travel time saving (43%), few crashes (70.4%), reduced crash severity (71.4%), improved emergency response (66.9%), low emission (66.3%), low insurance cost (55.5%), less traffic congestion (51.8%) | System failure (80.7%), legal liability (74.1%), system security (68.7%), vehicle security (67.8%), data privacy (63.7%), interacting with conventional vehicles (69.7%), interacting with pedestrians/bicyclists (69.8%), learning to use AV (53.5%), system performance in poor weather conditions (62.8%), unexpected situation (75.7%), no driver control (54.3%) |

| [38] | China: Few crashes (85.7%), reduced crash severity (85.1%), improved emergency response to crash (88.8%), shorter travel time (78.3%), low insurance cost (78.5%). India: less traffic congestion (72.3%), better fuel economy (85.9%) |

China: system failure (68.0%), legal liability (55.1%), interacting with pedestrians and bicyclists (42.6%), system performance in poor weather (59.6%), AVs confused by unexpected situations (56.1%) India: system security (54.6%), Vehicle security (57.3%), data privacy (50.9%), learning to use AVs (43.6%) |

| [12] | Safe (75%), convenience (61%), amenities (e.g. ability to text messages or multitask while riding) (53%) | Liability (70%), cost (60%), lack of control (53%) |

| [42] | Increased mobility (58%), reduced fuel consumption and emission (56%), low bus fares (64%), low insurance rates (53%), low parking costs (49%), safer driving (36%), reduced taxi fares (36%), allows to do other things (20%), improved safety (80% for automated bus, 89% for automated car) | Equipment/system failures (66%), legal liability (56%), vehicle security (54%) |

| [25] | Comfortable with data sharing for policy purpose (48%) | Privacy concern (89%), unwilling to pay to anonymize location (39.8%), oppose data sharing for advertising purposes (50%) |

| [32] | Reduced traffic crashes and improved comfort and convenience (37.3%), no need for driver’s license (12%), reduced mobility and crashes related problems of elderly persons (50%) | Technological dependability (43.48%), vehicle safety (31.43%) of Full AV, cost of new and not-yet-available technology (25.26%) |

| [55] | Enjoyable (75.7%), advance technology (54.4%), comfortable (19.5%), reliable (49%), omnipresent in future (41.4%), comfortable to transmit information to other vehicles (50.4%), to vehicle manufacturers (42.9%), to insurance companies (36.4%) and to toll operators (33.3%), trust technology companies (62.3%) and luxury vehicle manufacturers (49.5%), willing to use for everyday trips (40%) | Fear of technology (58.4%), not realistic (44%), unwilling to use for short distance (42.5%) and long-distance (40%) trips |

| [2] | Talking to others (59.5%), looking out the window (59.4%), fuel economy (53.9%), crash reduction (53.1%), emergency notification (71.5%), vehicle health reporting (68.5%), use of AVs for all trips (33.9%) and social or recreational trips (24.7%) | Street congestion (36.1%) |

| [62] | Improved safety (43.3%), reduced driving stress (40.6%), better technology (30.8%), collision avoidance (52.9%), improved fuel efficiency (46.5%), lane-keep assistance (26.5%). | Data privacy (58.4%), trust issue (46.6%), reliability (48.7%), higher travel time (64.8%) |

| [59] | Reduction of human error in crashes (35.64%), multi-tasking (30%), reduction of risk-taking behaviors (29.3%) | High cost (59.21%), lack of trust (32.1%), no control of vehicle (37.22%), technology malfunction (34.26%), safety for self and others (20%), safety of vehicle (21.39%), loss of driving skill (14.1%) |

| [1] | Reliability (California: 30.1%, Germany: 25.0%), problems when entering/exiting the highway (Cal: 23.9%, Ger 25.4%), issues with cut-in vehicles (Cal: 15.3%, Ger: 18.7%) | |

| [24] | Feel safe (84.2%) | Lack of confidence in technology (10.5%) |

| [72] | Lack of trust in technology (41%), safety (24%), cost (22%), Concern about using internet and internet enabled technologies (51%), privacy concerns (71%) | |

| [63] | Easy to use (71.06%), easy to become skillful using AV (60.35%), use of travel time for secondary activities (41.85%), fun to drive (53.21%), enjoyable (52.54%), use for everyday trips (53.45%), meet daily mobility needs (53.27%), entertaining (51.04%), reach destination safely (48.67%) | |

| [11] | Improved traffic safety (62%), safe to share with other modes of transportation (43%), reduced traffic fatalities and injuries (67%) | Set regulation for AV testing (70%) |

| [60] | Trust (51.32%), lower insurance rates (45.28%), willing to pay more (69.24%) | Increased risk (43.86%) |

| [48] | Reduced congestion (22.96%) | |

| [69] | Novelty technology (75.7%), low pollution (18.4%), integration with public transportation (3.7%) |

| Author | Heard of AVs (%) |

|---|---|

| [33] | 71.4% |

| [34] | 94.3% |

| [35] | 63% |

| [36] | 80% (Google car), 47% (CAV) |

| [37] | 52.2% |

| [17] | 66% overall (70.9% in USA, 66% in UK and 61% in Australia) |

| [38] | 87% (China), 73.8% (India), 57.4% (Japan) |

| [42] | 87% |

| [47] | Over 95% |

| [52] | 98.8% |

| [51] | 49% |

| [53] | 90% |

| [2] | 59% |

| [60] | 94.67% |

| [59] | 78.4% |

| 1 | Level 0 indicates no automation and the vehicle is fully controlled by a human driver. In Level 1 of autonomy, the vehicle has some driver assistance system for either steering or acceleration/deceleration. Partial autonomy is ascribed in Level 2, where the vehicle has driver assistance systems for both steering and acceleration/deceleration. In Level 3, the vehicle has a specific performance by the automated driving system with the expectation that the driver will respond. Level 4 indicates higher automation of the vehicle, which has a specific performance by an automated driving system, even if a driver does not respond. Level 5 indicates the full automation of the vehicle and the vehicle is operated by an automated driving system without human interventions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).