1. Introduction

Design Review Panels have been adopted in the United States, Europe, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand to help meet design and construction objectives. In this paper, the phrase "Design Review Panel" (DRP) specifically refers to the Urban Design Review Panel in New Zealand, which acts as a regulatory body for assessing design plans within the scope of urban design and planning. However, the literature review acknowledges the wider use of design review panels in different areas, considering their various contexts beyond the urban environment. The phrase "Design Review Panel" can mean different things depending on the region or organization. The notion of enhancing urban areas through a development approval system was first suggested in the 1960s in New York (White 2015). Urban design governance employed the same tool in Vancouver in the 1970s [

2] and in the United Kingdom in the late 1990s by the Commission for Architecture and Built Environment (CABE) [

3]. Afterward, the review panel's CABE system became a worldwide standard and was strongly suggested for use in Australia [

4]. Despite this, New Zealand has adopted the American system employed in Seattle, which is based on a city-led approach for specific development initiatives [

5]. In 2000, Auckland, New Zealand, established the first design review panel, and since then, many other cities in the country have followed suit.

Even though the DRP is widely used, it is only part of a larger system of safeguards that governments worldwide implement to regulate private sector design with the goal of achieving greater public benefit [

6]. Control measures can vary from regulatory systems such as zoning codes and statutory planning to discretionary tools such as peer design reviews, design guidelines, and master planning. Different combinations of these mechanisms are often employed depending on the local planning process structure to guarantee the most successful design and planning results. There is a growing tendency for design controls and management practices to adapt to local political contexts, cultures, and bureaucratic procedures (Carmona and Renninger 2017; Punter 2007). Moreover, the most recent trends in urban environment governance are being reshaped by approaches that involve a wider range of stakeholders, including local communities, to participate in the decision-making process [

1] and work together to improve the quality of the design outcome.

Despite their eagerness to enhance the process, they face certain difficulties. Although there is general agreement on the importance of enhancing the design quality of the built environment, the value of a good design can be interpreted differently by the various stakeholders involved [

9,

10,

11]. In the construction industry, value prioritisation has usually been assessed in terms of capital expenses. These are mainly economic indicators of tangible factors such as property values, location, quality, function, aesthetics, and return on investment [

10,

12]. In comparison, the public sector and DRP focus on values that are harder to quantify but have broader benefits, such as quality of life, livability, sense of place, connectivity, and urban space [

13]. Consequently, this process is often confrontational and can be seen as the source of conflict between different stakeholders: the government, industry partners, and users of the built environment [

14,

15].

Moreover, it is not only a dialogue between the public and private sectors but also leads to disputes between professionals and the general public about what constitutes superior design. Even though the DRP is intended to help and supplement design objectives, conflicting defaulted priorities can lead to wasted efforts. Consequently, gaining a better understanding of how different stakeholders view the review process would provide valuable information about setting up an effective system for DRP to facilitate rather than impede the development process and achieve better design results. Very few empirical studies have been conducted on the DRP process from the perspective of industry stakeholders, particularly because of the lack of comprehension in the New Zealand context.

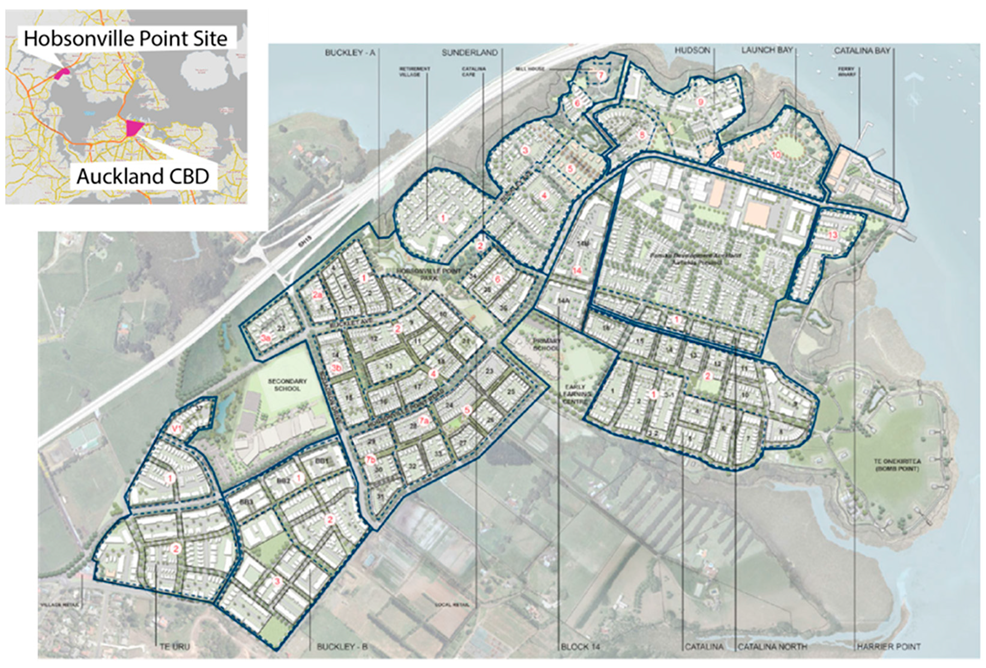

As a response, we took the largest masterplanned community, Hobsonville Point, in Auckland, New Zealand, as a case study (

Figure 1). This community is seen as a 'model' for housing development led by the government development agency seeking to achieve a new form of urbanism and level of sustainability in the New Zealand context [

16]. Investigating major developments such as this can provide an informative viewpoint to understand the various growth mechanisms, including the master planning process, provisions for public facilities, staging, quality of house design, and the role of the DRP in achieving a large-scale community to meet the design objectives. Furthermore, this study aimed to understand the impact of each development control 'tool', particularly design guidelines and the DRP process, on various stakeholders during development. This study focused on the diverse experiences of those involved in the development process, including development agencies, building partners, DRP members, and design professionals. This research utilises a literature review to analyse the role of the design review panel in both international and New Zealand settings. Second, 18 face-to-face interviews of property developers and users of the DRP were conducted using a semi-structured format to assess the impact of the design guidelines and DRP on the planning and development process and achieving the desire design outcomes.

2. International Experience with Design Review Panels

Over time, there has been a growing recognition of the significance of design governance in urban design literature [

8,

17,

18,

19]. This study conducted an extensive examination of the typologies of strategies and institutional arrangements of design governance and conceptualised the 'tools' – five formal tools (evidence, knowledge, promotion, evaluation, and assistance) and three informal tools (guidance, incentive, and control) – which are employed in practice. According to Carmona (2016), DRP is an informal instrument within a broader design governance system. Because DRPs are a widespread approach adopted worldwide, the integration of DRPs with the design control system can differ depending on the political context of different countries [

14], making it difficult to compare them at an international level.

For example, in American and Canadian cities, where city governments use zoning regulations to regulate the design outcome, DRP often include discretionary tools and written design guidelines in the planning approval process to enhance design quality [

20,

21,

22]. In the United Kingdom, design decisions are made on an individual basis, and master planning and design codes have been implemented as control measures (Carmona, 2009; Hall, 1996), with DRP being more widely adopted in the late 1990s. The planning systems in Europe also differ from one another and have less flexibility, as design control is often embedded in development plans and their corresponding guides, leaving little room for deviation (Punter 1999, 2007). The DRP was less active and only used for projects of considerable public interest. Additionally, Deng’s (2009) research on DRP in the Chinese context determined that it could only be successful when there was political backing for the intervention, and dialogue concerning design matters needs to be standardised.

Recently, urban design governance in North America, the UK, and Europe has been significantly altered by more intricate methods of public consultation, which allow the local community and other stakeholders to join forces with design professionals in the decision-making process [

1]. Specifically, the most recent research on DRP in Scotland [

27] demonstrates that the development of design reviews in Scotland marks a progressive move away from the customary adversarial context of peer review panels. The design review shifted from projects that were formally evaluated by a panel of experts in related fields to a three-stage facilitated process that emphasised iterative guidance and assistance. It is suggested that by altering the format of the DRP, a collaborative process can address the wider issues associated with the conventional assessment process, particularly the potential for conflict in peer review.

Although prior studies generally agree that DRP can help improve design quality [

1,

28,

29], it is essential to recognise that the crucial distinction between DRP and other design control tools is the immediate and direct feedback and the ability to provide advice based on specific circumstances. A review conducted by experts in the field can help bridge the major provision gap [

30] and provide clarification and guidance on official Development Plans and supplementary design instructions [

2]. It serves as a platform and form of communication that facilitates dialogue between various stakeholders; as Punter (2010) stated, 'So much poor design is the result of lack of thought, dialogue and positive collaboration between all parties in both design and delivery.’ In contrast to these claims, there is also strong criticism in many countries that there are no pre-established criteria for reviews that affect rigor and consistency [

22]. Furthermore, DRP have been heavily criticised because of their problematic nature, which has hindered innovation, being lengthy, costly, cost-inflating, overly restrictive, inconsistent, and relying on untrained reviewers [

31]. Even so, DRP is an effective 'tool' both on its own and when integrated into a larger design governance system to guarantee the quality of the design result.

3. Design Review Panel as applied in New Zealand

The urban design assessment process in New Zealand employs two main types of urban design panels: independent panels of external experts, including technical advisory groups, and in-house panels of external experts that function as 'design clinics.' While Hamilton City and Hastings District Councils operate in-house panels, several other cities, including Auckland City, Manukau City, Waitakere City, Queenstown-Lakes District, Christchurch City, Nelson City, and Tasman District use external panels.

In 2010, the Ministry of the Environment (lead government agency for urban planning in New Zealand) surveyed local authorities across New Zealand to understand the utilisation of review panels (Urban Design Panels: A National Stock take, Ministry for the Environment, n.d.). It was found that external urban design panels were not established in certain areas owing to factors such as limited resources, low demand, political opposition, legal constraints, and preference for alternative approaches such as in-house design reviews or peer reviews. External expert panels have primarily been established only in metropolitan centres because of development pressure, staffing levels, availability of expertise, and greater emphasis on urban design within district plans, such as the cities of Auckland, Queenstown, and Waneka.

The survey also highlights several management issues associated with the use of urban design panels in New Zealand. Local authorities have several options for urban design assessments at different stages of the application process. The value of an urban design review is particularly significant at an early stage, preferably before full design is developed. The flexibility to choose the most suitable method for urban design assessment and adopt a flexible approach by utilising different assessment methods or combinations thereof ensures robust advice that meets the timeliness requirements of the Resource Management Act (New Zealand’s legislation controlling land use). The Ministry of the Environment can provide support and coordination to local authorities seeking to enhance or expand their capacity for urban design assessments (Ministry of the Environment, n.d.). The need for clearer meeting protocols, improved clarity of panel minutes, consistency in approach for repeat meetings, challenges in assembling a panel due to availability, frustration with applicants caused by changes in panel membership, and potential disincentives for some panellists due to reimbursement levels can be improved.

Although this comprehensive survey was conducted a decade ago, it is evident that the Urban Design Review process serves as an important tool for promoting and regulating better designs in the built environment in New Zealand. Today, many local councils have adopted some form of urban design panel review, whether in-house or using external experts. The key challenge that NZ (New Zealand) still faces is the lack of public knowledge about the existence of such panels, and more effort is needed to raise awareness about the process and its benefits. Furthermore, empirical research on the application of design governance tools and their engagement with stakeholders in New Zealand is limited, highlighting the need for further investigation [

29,

32].3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Method

4.1. Case Study of Masterplanned Community Hobsonville Point

4.1.1. Background

Hobsonville Point is the largest master-planned residential development in New Zealand, situated 25 km northwest of Auckland's city centre. It is easily accessible via the State Highway 18 and provides ferry and bus services to the Central Business District. Hobsonville Point’s development is part of the government's broader urban growth management plan, which takes advantage of property opportunities in the region. The development site was approximately 167 hectares in size and was formerly owned by the New Zealand Air Defense Force in the 1930s. When the air base moved in the early 2000s, the available land presented a great chance for future urban expansion in Auckland and formed part of a wider Auckland growth management plan for the region approved in 1999 (Regional Growth Strategy (RGS)).

4.1.2. Urban Planning and Design Process

From 2000 to 2011, a great deal of effort was put into the initial planning process, including consolidating the land, requesting plan modifications, and creating a government subsidiary entity (Hobsonville Land Company (HLC)) from the authority to carry out Hobsonville Point development [

33]. As this was the first effort to "coordinate" the growth of the future urban region, the government has adopted an innovative approach to planning for development – a public-private partnership. Under Plan Chang (PC-13) to the approved statutory land use plan (District Plan), the Hobsonville Point development site was designated as a Special Area instead of a regular land-use zone to enable comprehensive planning for growth and development trends. Furthermore, measures to ensure high quality pedestrian facilities are implemented to connect important social amenities such as schools, parks, and community services between precincts, and to integrate them with public transport nodes and bus stops. The PC-13 established universal criteria for the Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) and specified additional requirements for each precinct depending on its location and characteristics. An initial masterplan was suggested, which adhered to the principles of the Urban Concept Plan but allowed for some flexibility when determining the specifics of each block.

According to the masterplan, the development was divided into 'precincts’, each of which contained multiple blocks. Developers were asked to submit a CDP that would outline a comprehensive planning process with land subdivision patterns, key uses, and associated development requirements, including design guidelines. The CDP application allows for flexibility in deviating from the Urban Concept Plan, including the precinct boundaries, if the design outcomes comply with fundamental planning principles. The CPDs and Design Guides serve as references for the in-depth architectural design of each block. To avoid the dull repetition of dwelling designs, various building patterners execute architectural designs.

To ensure that the vision and quality of Hobsonville Point were upheld, the Council and HLC had to implement a governance system for the development structure. Consequently, in 2013, non-mandatory project-based review panels were set up as a professional design advisory group to provide impartial counsel during various phases of the design process. The Design Review Panel (DRP) consists of three members, one each from the Auckland Council and the HLC and one from the Auckland Council Urban Design Specialist. The review process occurred at three distinct design stages: concept design, development design, and finalised development design. The goal of the DRP is to evaluate and analyse the proposed developments and offer unbiased advice to developers and the council to enhance the quality of design elements, such as architecture, landscape, and urban design.

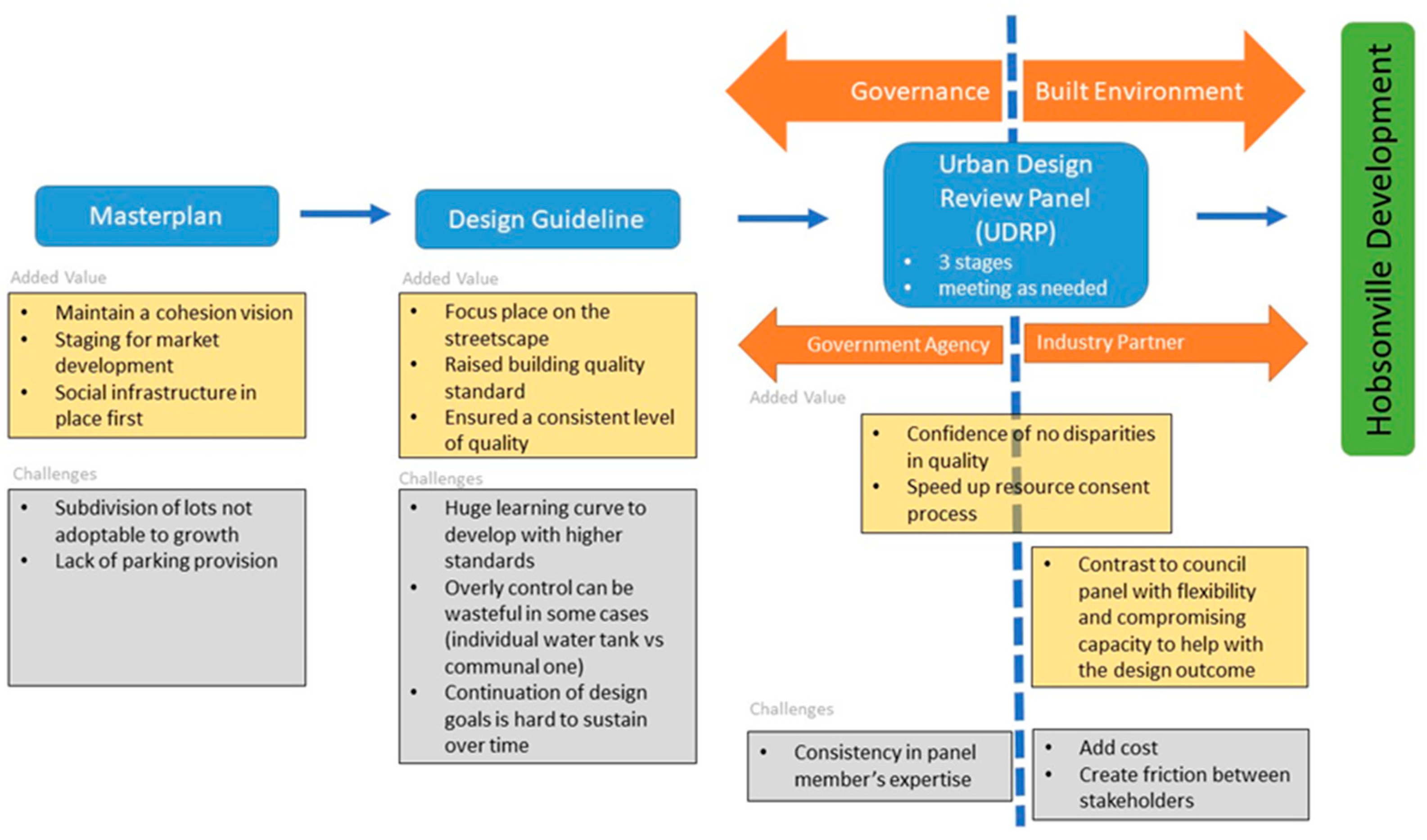

This strategy, which is based on a government-led model, has the advantage of allowing the establishment of general zoning regulations while still providing leeway in the overall masterplan and specific block design. The non-statutory DRP review process provides support and helps ensure that the design outcome is secure, which boosts confidence in meeting the development objectives with consistent quality over time. Another important note is that, although the DRP does not have statutory power, developers are required to go through the process before they can successfully acquire the land. This adds an additional controlling mechanism to ensure a desirable design outcome and that the masterplan and design guidelines are followed. This approach is particularly advantageous for medium- and long-term development projects. In comparison, the traditional development process is likely to involve a series of small, localized designs that do not account for public benefits and lead to a negative design result. As shown in

Figure 2, the process is visualized.

4.2. Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews with 18 building industry stakeholders from Hobsonville Point Development (

Table 1) were conducted with respondents from both New Zealand and Australia between January and February 2019. To ensure that a variety of perspectives were included in the analysis, the stakeholders interviewed included developers, local government design and policy experts, advisory bodies, architects, and industry organisations. The interview questions are provided in Attachment A.

The interview questions were developed with two key objectives.

The goals of this study are to assess strategies for enhancing value and design outcomes, such as utilising urban design guidelines and DRP as effective tools, not only from the government's viewpoint but also from the industry partner's point of view. The interview outlines essential questions that should be asked of everyone involved, while still allowing for the possibility of delving into other topics in depth, since each interviewee has its own unique expertise and knowledge. The interview transcripts were then summarised across the three governance tools: the masterplan, design guidelines, and design review panel. The University of Auckland provided ethical approval for this project.

5. Method

It was determined from the outset that Hobsonville Point would use a design-based approach, creating a masterplan with predetermined objectives and results, while still allowing for some degree of flexibility to guarantee design excellence. This was followed by more specific implementation tactics utilising a Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) and design guidelines (DG) to realise the vision of development. Ultimately, DRP was created to ensure integration and inclusion in each development block.

5.1. Masterplan – Roles, effectiveness and limitation

There was an agreement that the masterplan was critical for overall success, with one comment stating, "Hobsonville is an exemplar of a world-class development”, attributing it to being a government-led project. The masterplan and provision of infrastructure (schools, parks, and amenities) were perceived as key factors contributing to high-quality design outcomes. First, it was stated that the masterplan allowed the building partners to understand where the buildings sit in a wider context and provided an understanding of the street widths, neighbourhood nodes, and employment components. This was cited as key in the preliminary stages, as building partners "knew where they were sitting in the paddock and what the vision was," in terms of amenities, the developers "felt like they were all in the same boat."

Most asserted that having social infrastructure in place was essential for drawing the market and was a major factor in enticing developers. The developers "trusted the crown to deliver a good job with infrastructure, unlike the private sector, who might cut corners". Having the masterplan and thus public infrastructure was the reason "why people paid a premium to buy into the community".

"Putting infrastructure first, in terms of social infrastructure, placemaking infrastructure, cafes etc., was critical cause it convinced people if they live in a small plot, there are places provided. Therefore, it is critical to persuade people to live at a higher density." – HLC.

Additionally, many have argued that masterplans are essential for staging commercial cash flow and market demand. The superblock structure was designed to accommodate various typologies that were essential for the initial stage of development, since developers were hesitant to construct medium-to-high-density housing in New Zealand. As the market shifted and builders' confidence grew, density and typologies were adjusted accordingly.

Despite the advantages of a flexible masterplan, there have been numerous criticisms and key lessons to be learned. Initially, comments were made about subdivision patterns that were not suitable for accommodating a variety of typologies. 'Subdivision patterns are critical at the beginning because later there are challenges such as building types require two fronts and how do you accommodate parking with the established lot depths.' In particular, the success of walk-up housing and car parking is a source of tension. 'The masterplan was predicted on terrace houses and single houses.' Additionally, questions were raised about the east-west orientation of the block patterns and the extensive use of concrete in the alleyways. Regarding laneways, one said they are more successful than Stonefield (a similar residential area in Auckland) and that having garages behind the houses 'creates a much more attractive streetscape, a pedestrian amenity.' Other issues with the masterplan included the fact that property prices kept rising beyond what was deemed affordable as well as minor discrepancies between the design guidelines and the actual built form in some precincts (i.e., some precincts had to 2-3 steps instead of the required 5-6). Additionally, one of the building partners mentioned that they had difficulty providing infrastructure (berms and footpaths) and proposed that it should be planned more thoroughly at the masterplan level.

In response to density targets almost doubling in the development (3,000 to 4,500 housing units), there was a general agreement that the masterplan responded to this successfully, citing flexible superblocks as the key. One comment stated that the success of the increased density lies within "HLC being staunch on certain things, the network of parks, linkages and walkways, haven't changed." Nevertheless, some have pointed out that the lack of parking spaces and road width is becoming an increasingly important issue. One person stated that because the masterplan and preliminary stages were so successful, "the intensity of the development and the idea that more profit could be made and more people could live there was pushed without really thinking of the overall masterplan and how that would be affected, along with infrastructure and historical constraints." This is supported by the consensus that providing job opportunities in a particular area has a significant positive effect on outcomes.

Apart from the masterplan, the success of the development was also due to marketing, staging, and offering of a unified vision. 'The role in marketing was critical in pushing the communities' expectations and community acceptance of the typologies proposed.' It was agreed that marketing a new neighbourhood and lifestyle was essential for drawing young families to the region and encouraging the rise of apartment living. A frequently cited example is Scott's point development near Hobsonville Point, which is not subject to master planning or design processes. As one person stated, 'Scott's Point is going to be dog's breakfast… every person is fighting for themselves, there is no cohesion. whereas the masterplan offers a design-based approach.'

5.2. Design Guideline – Roles, effectiveness and values

5.2.1. Design Outcome

As previously mentioned, this was an unprecedented development process, and great care was taken to ensure that the building partners agreed. All participants reported that they were familiar with the innovative bidding process and had been briefed on relevant documents through a workshop hosted by the HLC. The session outlined the DRP process and discussed the CDP and DG in the first stage. Even if the stakeholders were unfamiliar with the design guideline concept, the majority concurred that this was an unfamiliar process, and since the guidelines were quite comprehensive, 'getting the building partners educated on those guidelines was quite a painful process.' Despite this, the majority concurred that after becoming familiar with the process, it was simpler, and ultimately, these guidelines were essential for 'achieving good urban design outcomes'. This gave the developers and construction partners ‘confidence that it is worth investing in the design' and assurance that the design results will have the same high quality with no ‘borrowed amenities’ from neighbouring developments.

Most respondents agreed that design guidelines (DG) had a considerable impact on design results. These guidelines offered clear standards to guarantee that the quality of high-level development was consistent and to assist building partners in attaining it. Furthermore, it was generally agreed that the DG provided structure and guidance for the design outcome and essentially shifted building partners to accept medium-to high-density housing. New Zealand has limited experience with high-density development typologies, which are relatively new concepts. It is also important to note that prescriptive and robust DG has helped minimise the risks of potential negative outcomes, making it difficult to create.

Despite the largely positive feedback from stakeholders, it poses a challenge for both the building partners and HLC to implement. Developers and building partners had to go through a steep learning curve to streamline delivery processes. Generally, it was agreed that the DG was too strict in some areas; however, they were seen as clear and relatively general, with enough leeway for building partners to explore a range of options. One designer viewed the prescriptive approach as beneficial, because it eliminated any uncertainty from the project. The building partners soon realised that their internal teams were not capable of meeting the challenge and, as a result, had to quickly come up with a new strategy outside their comfort zone to bring in new architectural teams. This resulted in improved design results, with building partners expressing that the experience was a pleasant surprise which could have affected their business plans.

Clearly, most stakeholders involved in the building process, particularly designers, valued the DG after the initial challenge and saw the document as a strategic process that shaped the design. One respondent commented that the document was 'incredibly liberating' and 'refreshing’, as it enabled a variety of typological outcomes while facilitating constructive debates. Although certain regulations were quite specific, it was observed that 'the composition within those rules created a lot of flexibility for an architectural interpretation.'

Additionally, HLC was a key factor in this transition, fostering positive connections through handheld activities. The DG also established a framework with a well-defined purpose and expected results, which stakeholders could use to evaluate the worth of the scheme.

"The guidelines enabled the panel and the council to consent staff to explain why they were asking for change and to force builders to think more carefully about their design. The density provisions also forced them out of their comfort zones into terrace housing and apartments." – John Mackay

5.2.2. Value Added

There was a consensus that the design guidelines added value as they ensured consistent quality throughout development. The DG delivered an expectation, ensuring that people knew what they were buying, what should be delivered, and how they contributed to the fabric and overall intent. One person stated that the success of the DG lies in the design outcomes throughout the neighborhood being 'different but coherent.' On the other hand, Hobsonville Point was compared to the 'Truman Show' on multiple occasions, referencing repetitive and formulating built-form outcomes.

It was generally agreed that the design guidelines were beneficial, as they guaranteed a consistent level of quality throughout the development process. The DG set out expectations so that people would be aware of what they were purchasing, what should be provided, and how they would contribute to the overall plan and purpose. One individual commented that the success of the DG is based on the design outcomes in the area being 'different but coherent.' Conversely, Hobsonville Point was compared to the 'Truman Show' multiple times, noting its repetitive and formulaic built-form outcomes.

"The design guidelines are more than just setting a benchmark for a certain level of quality; they are actually about constructing a particular place." – Natasha Markham

"I think the design guidelines were slightly more aggressive than they could have been, but if there was none, you'd have nothing to rely on."

It is generally accepted that with the help of DG, the development fulfilled many of the requirements for livability, sustainability, community, sense of belonging, and so on, in various areas. The neighbourhood's desirability was enhanced by encouraging lifestyle choices and various typologies, blue and green networks, and public streetscapes. Sustainability has also been praised as being highly successful at multiple levels. On a macro level, social sustainability was achieved by fostering a developing housing market at the micro level, incorporating environmentally sustainable features such as rain tanks, external heat pumps, and insulation standards. However, some argue that it would be a waste of space and money to provide individual water tanks for each lot, whereas having a unified network throughout development would be a more efficient use of resources. One individual successfully promoted sustainability by advocating for the use of louvres and the articulation of facades instead of plain flat facades that lacked sun control. The design guidelines also concentrated on streetscapes and interactions, which are essential for comfort and Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED).

Most people believed that DG was beneficial to the project, but it was argued that it depended on the specific circumstances. This was demonstrated by the block orientation, where the efficiency of DG varied depending on the orientation topography. The masterplan block patterns advocate an east-west orientation, dispelling the widespread misconception that this is the optimal approach. Another comment noted the visible evolution of DG, noting that the built form has improved in quality compared to the earlier stages of development. Buckley A (the first precinct constructed, see

Figure 1) is known for its lack of services and amenities, and if Clark Road is not completed, it reduces the occupants' quality of life. Furthermore, it was noted that

"The world has changed considerably from 2009, density has increased, while those design guidelines were mostly written about terrace houses, where most of the panel see apartments." Worries have been expressed regarding the extensive use of concrete surfacing in laneways on a small scale. Additionally, despite the CDP's advocacy for natural materials, lightness, and openness, the extensive use of bricks in development suggests that no written instructions can determine the outcome.

Most researchers concluded that DG could be beneficial to the project, but it was suggested that it should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. This was demonstrated by the block orientation, where the effectiveness of DG varied depending on the orientation topography. The masterplan block patterns advocate an east-to-west orientation, noting that there is a misapprehension across Auckland that this orientation is the optimal approach. Another comment noted the visible evolution of DG, noting that the quality of the built form improved compared to the earlier stages of development. Buckley A (the initial precinct built) was known for its lack of services and amenities, and with Clark Road not completed, it reduces the occupants' quality of life. Additionally, it was noted that "The world has changed considerably from 2009, density has increased, while those design guidelines were mostly written about terrace houses, where most of the panel see apartments." There has been an outcry over the extensive use of concrete surfacing on laneways on a small scale. Additionally, despite the CDP's encouragement of natural materials, lightness, and openness, the extensive use of bricks in development suggests that no written rules dictate the outcome.

Nonetheless, it was reported that the sustainability goals were substantially retracted because the tool for urban sustainability was completely removed once the Waitakere City Council was no longer operating since no one was maintaining that task website; the parameters became unrealistic for some elements. This caused the RC and CDP to be taken out of all precincts because they were not quantifiable, and no department could take responsibility for them, making the designs (large apartments) more challenging in many ways.

A major critique of this progress was the lack of job opportunities, as Hobsonville Point initially intended to have a high concentration of marine-related employment. Although it was suggested that setting up a reliable employment model would be beneficial for the community, it was observed that marine precincts did not come into existence for a variety of valid reasons. In contrast, one individual argued that employment is a separate matter, and the CDP did not really stimulate commercial use, citing Hobsonville Point Road zoning for mixed commercials as ineffective, asserting that it must be driven by the market, and that there needs to be inherent demand.

5.3. Design Review Panel (DRP)

The Auckland Council and the HLC created the DRP to ensure that the quality of Hobsonville Point's development outcome was in line with the masterplan and could evolve as necessary with managed guidance and safeguards in place. The respondent commented that having the panel support the design guidelines was essential, as it established a robust system that established the desired character of Hobsonville Point, making it distinct from other areas. Initially, developers were resistant, but eventually they realised that the DRP process ensured that there would be no discrepancies in quality among the developments, thus creating a level playing field.

Most interviewees reported that the DRP was not only essential but also a generally positive experience. This was because of the informal nature of the meetings, which consisted of three sessions, resulting in a greater level of detail that made the project outcomes more clearly defined. Although this process took longer than the Council Review Panel, it was said to be less intricate and involved "an open conversation… where people rolled up their sleeves to get solutions." It was also noted that the panel sessions were adaptable, with one project taking five sessions and key insights being incorporated into the subsequent project, leading to only two sessions being required. The panel emphasised the importance of flexibility and compromise, noting that they "encouraged new designs, innovation, and density into the development without being so pedantic in ticking every box". This contrasts with the Council Review Panel, which characterizes it as a 'binary' process.

"The panel consists of people who understand the balance of good design outcomes and buildability where they can make pragmatic decisions, encourage new designs and innovation, density into the development without being so pedantic that you don't have to tick every box, there are compromises."

Specifically, building partners noted that the resource consent process was arguably easier with support from the DRP, as affordability and deliverability were factored into the DRP process. "The process has been seamless, which is an advantage for developers." Because of the DRP process and the level of detail involved, architects were confident that their designs were deliverable, and this resulted in every RC being consented as Council "had the confidence of its buildability and feasibility."

Most people agreed that the DRP process was beneficial, although it did not come without difficulty. During the meetings, "there have been heated arguments and discussions, pushbacks and agreements", with one individual characterizing the process as "very invasive" in total. A major complaint regarding the DRP process was the extra expense imposed on developers and building partners during the negotiation stage. As you operate in the present environment, the market and costs can fluctuate significantly within six months. Additionally, the DRP advocated for a more intricate design for the façade, which sparked heated debates as the investor was unwilling to pay for it. If there was any minor alteration in the design, the building partners were required to go through the panel again, which was seen as 'very strenuous' and 'untenable'. This has caused larger housing providers to neglect the assessment of external changes, with the HLC only becoming aware of them through compliance monitoring.

During the interviews, there was a lot of disagreement about the DRP's level of expertise, and many people noticed significant discrepancies between certain panels. 'It came down to certain personals on the DRP; in some cases, they wouldn't budget on what the previous panel approved. It was noted multiple times that some panel members ventured into areas outside their expertise, which was seen as insulting to certain design professionals. One individual remarked that the rate of personnel turnover at Auckland Council was "frustrating" and "mind-numbingly bad" since "different people coming in partway through the process and completely undermining previous conversations." In conclusion, it was noted that the panel members' levels of skill and expertise varied over the years, leading to a weakening of the panel, and that a strong leader was needed to direct and guide the meetings to make them productive.

5.4. Other Concerns

The respondent noted that the "positive" relationship between builders, developers, and HLC is a factor that contributes to the success of development. "Open book relationship, very collaborative, meeting fortnightly and sometimes on-site to try to help out with solutions." This has also formed a bond between schools and builders to promote youth construction.

"We work a lot closer with builders and look at alternative arrangements, we are a lot more active, and we will commission additional work they don't have to pay for as well as getting a third party to peer review”. – HLC.

Another identified benefit was the advantage of single-land ownership. It is generally agreed that a positive outcome is more likely to be achieved when CDP is delivered by organisations that prioritise good design outcomes, rather than private developers, who are typically motivated by financial gain. Both public and private relationships are essential to achieving design-driven results. People were willing to pay extra due to streetscapes and public amenities such as the urban public realm, schools, and coastal walkways. Notably, no private developer commissioned this to a high degree of quality. This distinctive development process has a beneficial effect on development outside the Hobsonville Point. This is attributed to the opportunity for builders and building partners to gain knowledge and broaden their skill set in terms of novel typological results, and the HLC advice was consistently encouraging.

6. Discussion

The interviews revealed several advantages and difficulties associated with the use of the masterplan, design guidelines, and DRP in planning and development processes. Each strategy plays a different role in contributing to the positive outcome of improving quality of development. The masterplan seeks to provide a comprehensive vision and program with a clear implementation path. Design guidelines are more directive, leaving little room for creativity among different design elements. These standards are employed to regulate the design quality with a minimum requirement that guarantees uniformity in the design quality for all development sites and user experience. Although the majority of stakeholders valued both these strategies, it has been more difficult for industry partners to respond to them due to divergent prioritisation. The motivation to achieve higher design quality in the public realm (street, landscape, and public space design) and building design may not necessarily come from a market-driven agenda that reduces the value of building industry partners.

In this situation, the DRP serves as a vital link between the development agencies, developers, and design partners. This aligns with lessons learned from other cities worldwide (Guy et al., 2012). It can bridge this gap and address the limitations specified in the design guidelines and masterplans (Design Council, 2013; Design Review in South Australia, 2011), which are often used in the absence of a document. The review process allows for "conversations", which are responsive and adaptive to each situation. This offers the opportunity to investigate alternative solutions to the intricacies of different stages of development. It is not unusual to find that some projects are unable to comply with the design guidelines because of unfavourable circumstances. In this instance, the DRP can offer more meaningful assessments of facts, not just a numerical figure that meets the performance criteria, but also a solution that works in practice [

29]. Furthermore, the DRP can make the approval process smoother when the local planning authority relies on the DRP's professional advice and views the review as part of the approval process, although this is usually not a legal requirement. It is evident that developers can gain more benefits from the DRP process if they incorporate it into the initial stages of design. This reduces the chances of developers wasting their time and effort on designs that do not comply with regulations and gives industry partners assurance before they apply for official development authorisation.

Nevertheless, all the assertions discussed are contingent on DRP members being experienced professionals with pertinent knowledge of the project to prevent the negative consequences of causing considerable pressure and vexation in the design process. Some remarked that the expertise of DRP members is inconsistent, and that frequent changes in members can lead to frustration and stress. The key shortcomings of the panel include additional expenses, negotiation challenges for developers and building partners, fluctuating market costs, and the need to go through the panel again for minor design alterations. Discrepancies and concerns regarding expertise arose among certain panel members, leading to inconsistent decision making, and the turnover rate of personnel at the Auckland Council created frustration and undermined previous conversations. These factors contribute to the perception of a weakened panel, emphasising the need for strong leadership to ensure productive outcomes. These comments also align with the international criticism of design reviews [

22,

28,

31] but with specificity to the context of New Zealand.

Despite these flaws, the overall consensus from the interviews, particularly from the industry partners, was that the DRP process was beneficial, potentially making the resource consent process easier for developers while also promoting flexibility and fairness among all.

7. Conclusion and Future Research

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the benefits and drawbacks related to master planning and design guideline approaches, underscores the essential role of the DRP as a mediator between different stakeholders, and assists in achieving the desired urban planning goals for the redevelopment of Hobsonville Point. Although most stakeholders recognise the value of these strategies, they may struggle to reconcile their priorities with the objectives outlined in the masterplan and design guidelines. In this situation, DRP is essential for creating a connection between development agencies, developers, and design partners. Its purpose goes beyond simply meeting the performance standards to focus on creating practical and successful design results.

Hobsonville Point exemplifies the efficacy and value of a design-based approach to high-quality urban development with clearly defined objectives, guidelines, and review mechanisms. This demonstrates that this approach can foster a unified and desirable community while initiating new high-density and sustainable lifestyles, both of which were unusual in New Zealand at the time. The knowledge gained from the Hobsonville Point project served as a useful model for future urban development projects, demonstrating the effectiveness of the "right-mix" of governance mechanisms and collaboration. Nonetheless, it is critical to recognise the importance of single-land ownership and the critical leadership role played by HLC in achieving the desired outcomes. Not only do our findings highlight the importance of DRP in achieving successful design outcomes, especially when they are incorporated in the preliminary stages of the design procedure. The study's findings also highlight the importance of effective communication, thorough preparation, and organised processes to achieve successful design outcomes. Furthermore, concerns about the expertise and reliability of DRP members must be addressed to improve planning and development processes that may result in better outcomes and higher-quality designs.

Regarding these mechanisms' future developments, it is crucial to evaluate the proposed developments' potential environmental effects, consider climate change estimates, and encourage resilience planning. Masterplanned communities can strengthen their resilience and contribute significantly to international efforts to combat climate change by analysing their sensitivity to climate hazards and incorporating adaptive design solutions. Masterplanned communities can reduce glasshouse gas emissions, enhance sustainability, motivate international efforts to combat climate change, foster the development of resilient communities, and make significant contributions to the global context by prioritising climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Appendix A: Survey Questions:

Were you aware of the urban design guidance documents, including the urban design review panel process before you became involved in the project?

If so, how do these guidelines influence the project design?

If not, what influenced your project's design instead

Did the urban design guidelines add value to the project's design or do they negatively impact your design?

Was there value in, and did, the urban design review panel assist in improving the quality of urban design outcomes?

Do you think urban design guidance assists the council in achieving its urban planning goals towards sustainability and livability expressed in its urban planning documents?

Where are you aware of the masterplan before you started this project, and do you believe there is value in mastering planning?

Is there anything else you would like to cover your involvement in these developments?

References

- White, J.T. Future Directions in Urban Design as Public Policy: Reassessing Best Practice Principles for Design Review and Development Management. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punter, J. From Design Advice to Peer Review: The Role of the Urban Design Panel in Vancouver. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz-Drinkwater, B.; Platt, S. Better quality built environments: design review panels as applied in Cambridge, England. J. Urban Des. 2018, 24, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. London, ‘Reviewing design review’, ArchitectureAU, Sep. 24, 2014. Accessed: Jun. 20, 2022. [Online]. Available online: https://architectureau.com/articles/reviewing-design-review/.

- Urban design panels: A national stocktake’, 2010. Accessed: Jun. 28, 2023. Available online: https://environment.govt.nz/publications/urban-design-panels-a-national-stocktake/.

- Jonathan. Barnett, ‘Urban design as public policy’, p. 240, 1974, Accessed: Jul. 03, 2022. [Online]. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Urban_Design_as_Public_Policy.html?id=0jlqAAAAIAAJ.

- Punter, J. Developments in urban design review: The lessons of west coast cities of the United States for British practice. J. Urban Des. 1996, 1, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Carmona and A. Renninger, ‘The Royal Fine Art Commission and 75 years of English design review: the first 60 years, 1924–1984’. 2017, 33, 53–73. [CrossRef]

- CABE, ‘The value of urban design’, 2001, Accessed: Jul. 03, 2022. [Online]. Available online: www.cabe.org.uk.

- Abdul-Samad, Z.; Macmillan, S. Improving design quality and value in the built environment through knowledge of intangibles’, IEEE International Engineering Management Conference, vol. 3, pp. 33 898–902, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Bole, S.; Reed, R. The Value of Design: A Discussion Paper. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2009, 52, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J. Editorial: Cost and Value In Building Green. Build. Res. Inf. 2000, 28, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Moore, T. Alves, R. Horne, and A. Martel, ‘Improving design outcomes in the built environment through design review panels and design guidelines’, 2015.

- J. Punter and M. Carmona, The Design Dimension of Planning: Theory, Content, and Best Practice. 1997. Accessed: Jul. 03, 2022.

- Madanipour, A. Roles and Challenges of Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 2006, 11, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Lietz, ‘Hobsonville Point- Beyond Sustainable Houses’, 2010. [Online]. Available online: www.hobsonvillepoint.co.nz.

- Carmona, M. The formal and informal tools of design governance. J. Urban Des. 2016, 22, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. Can we extend design governance to the big urban design decisions? J. Urban Des. 2016, 22, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, G. The curious subject of design ‘governance’. J. Urban Des. 2016, 22, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstreet, R.C.; Lai, R.T.-Y. Law in Urban Design and Planning: The Invisible Web. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1988. [CrossRef]

- John. Punter, ‘The Vancouver achievement : urban planning and design’, p. 447, 2003.

- Kumar, S.; George, R.V. Fallacious argumentation in design review. Urban Des. Int. 2002, 7, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Carmona, ‘Design coding and the creative, market and regulatory tyrannies of practice’, Urban Studies, vol. 46, no. 12, pp. 2643–2667, 2009, [Online]. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43197932.

- C. Hall, ‘Design control: Towards a new approach’, 1996.

- Punter, J. Design Guidelines in American Cities: A review of design policies and guidance in five west coast 73 cities’, Design Guidelines in American Cities, Feb. 1999. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. Design control in post-reform China: A case study of Shenzhen's commercial office development. Urban Des. Int. 2009, 14, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.T.; Chapple, H. Beyond design review: collaborating to create well-designed places in Scotland. J. Urban Des. 2018, 24, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, E.; Higgins, M. How Planning Authorities Can Improve Quality through the Design Review Process: Lessons from Edinburgh. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarhoff, E.J.; Beattie, L.; Hunt, J. Improving the Quality of the Built Environment using Urban Design Review Panels: An Appraisal of Practices in Australia and New Zealand. J. Eng. Arch. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, E. Design review in the UK: Its role in town planning decision making. Urban Des. Int. 2011, 16, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, B.C. Introduction: The Debate on Design Review. 1994, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, M. Urban design and the planning system in Aotearoa-New Zealand: Disjuncture or convergence? Urban Des. Int. 2010, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opit and R. Kearns, ‘New housing development at Hobsonville: promoting and buying into a “natural” community’. Nov. 29, 2013. Accessed: Jun. 28, 2023. Available online: www.hobsonvillepoint.co.nz.

- S. Guy, S. Marvin, W. Medd, and T. Moss, ‘Shaping urban infrastructures: Intermediaries and the 102 governance of socio-technical networks’, Shaping Urban Infrastructures: Intermediaries and the 103 Governance of Socio-Technical Networks, pp. 1–226, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Design Council, ‘Design review principles and practice landscape institute’, London, 2013.

- ODASA, Design review in south Australia. 2011.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).