Submitted:

02 July 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

- authors and year of publication

- type of study

- countries and facilities involved

- timing of treatments

- number of patients included

-

characteristics of patients included:

- age;

- gender;

- comorbidities;

- BMI (“body mass index”);

- ASA (“American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status”);

- diagnostic criteria used for acute cholecystitis;

-

type of percutaneous cholecystostomy:

- transperitoneal drainage;

- transhepatic drainage;

-

type of surgical treatment:

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy;

- open cholecystectomy.

- postoperative mortality;

- emergency surgical treatment;

- readmission for biliary complications.

- overall postoperative complications;

- major postoperative complications;

- emergency reinterventions;

- length of hospital stay.

RESULTS

Literature search

- -

- 32,634 treated with percutaneous drainage;

- -

- 4,663 underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy,

- -

- 343 underwent open cholecystectomy,

- -

- -

- in 7 studies transhepatic access was used;

- -

- in 2 studies the access was transperitoneal;

- -

- in the study by Loozen et al.[21] , both techniques were used;

- -

- 7 studies did not specify the preferred technique.

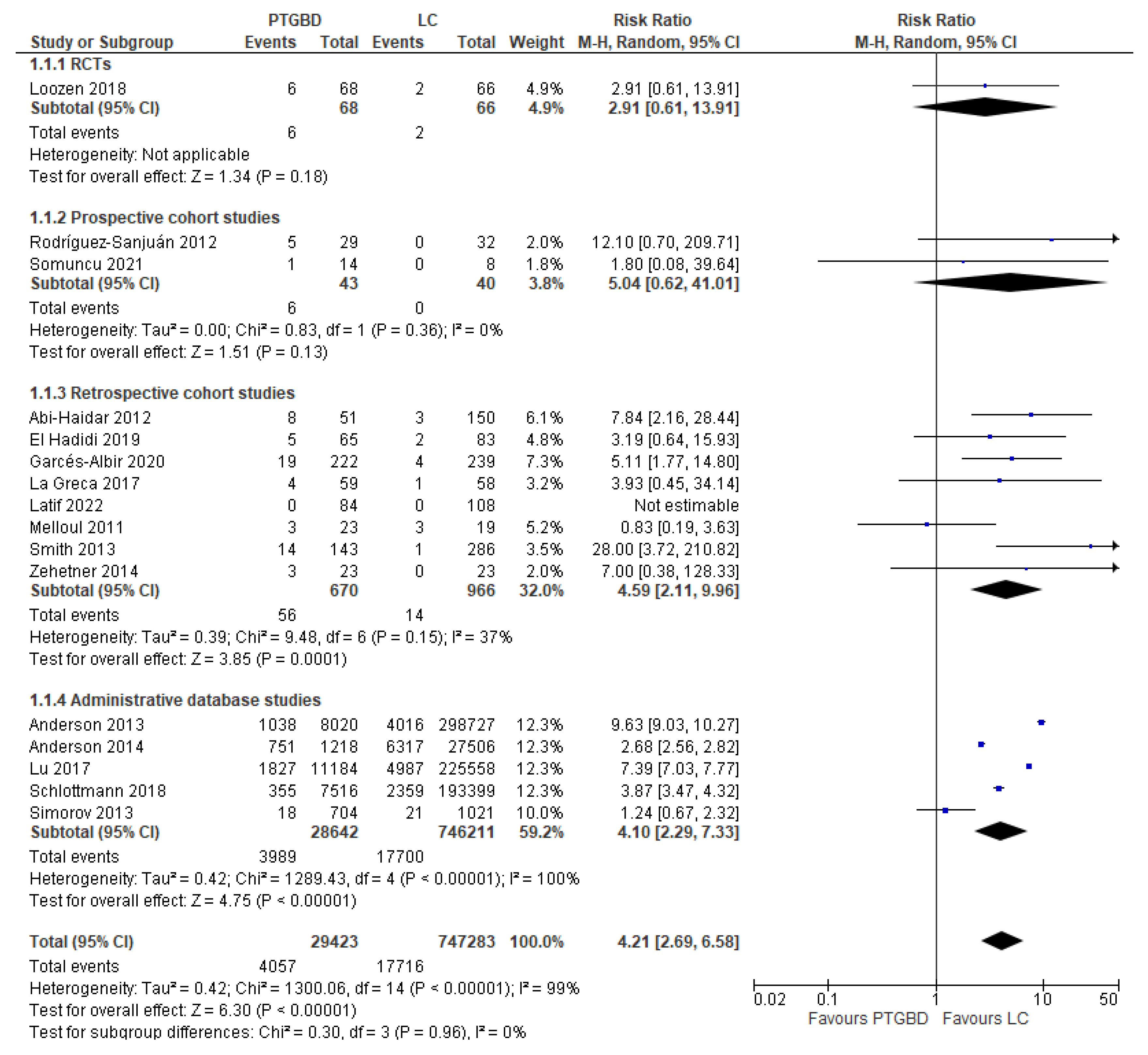

Analysis of results: Primary outcomes

- RCT: PTGBD group 8.82% (6/68) vs EC group 3.03% (2/66) (RR 2.91; 95% CI [0.61 to 13.91]; P 0.18).

- Prospective cohort studies: PTGBD group 13.95% (6/43) vs 0 (0/40) of EC group; this result was not statistically significant (RCTs: RR 2.91 95% CI [0.61 to 13.91]; P=0.18).

- Retrospective cohort: there was an advantage of the EC group (1.45%) (14/966) over the PTGBD group (8.35%) (56/870), but in this case the result was statistically significant (RR 4.59 95% CI [2.11 to 9.96]; P=0.0001).

- Studies from administrative databases: the mortality was 2.37% in the group undergoing cholecystectomy vs 13.92% in the group undergoing PTGBD, and this difference was statistically significant (RR4.10 95%CI [2.29 to 7.33]; P<0.00001).

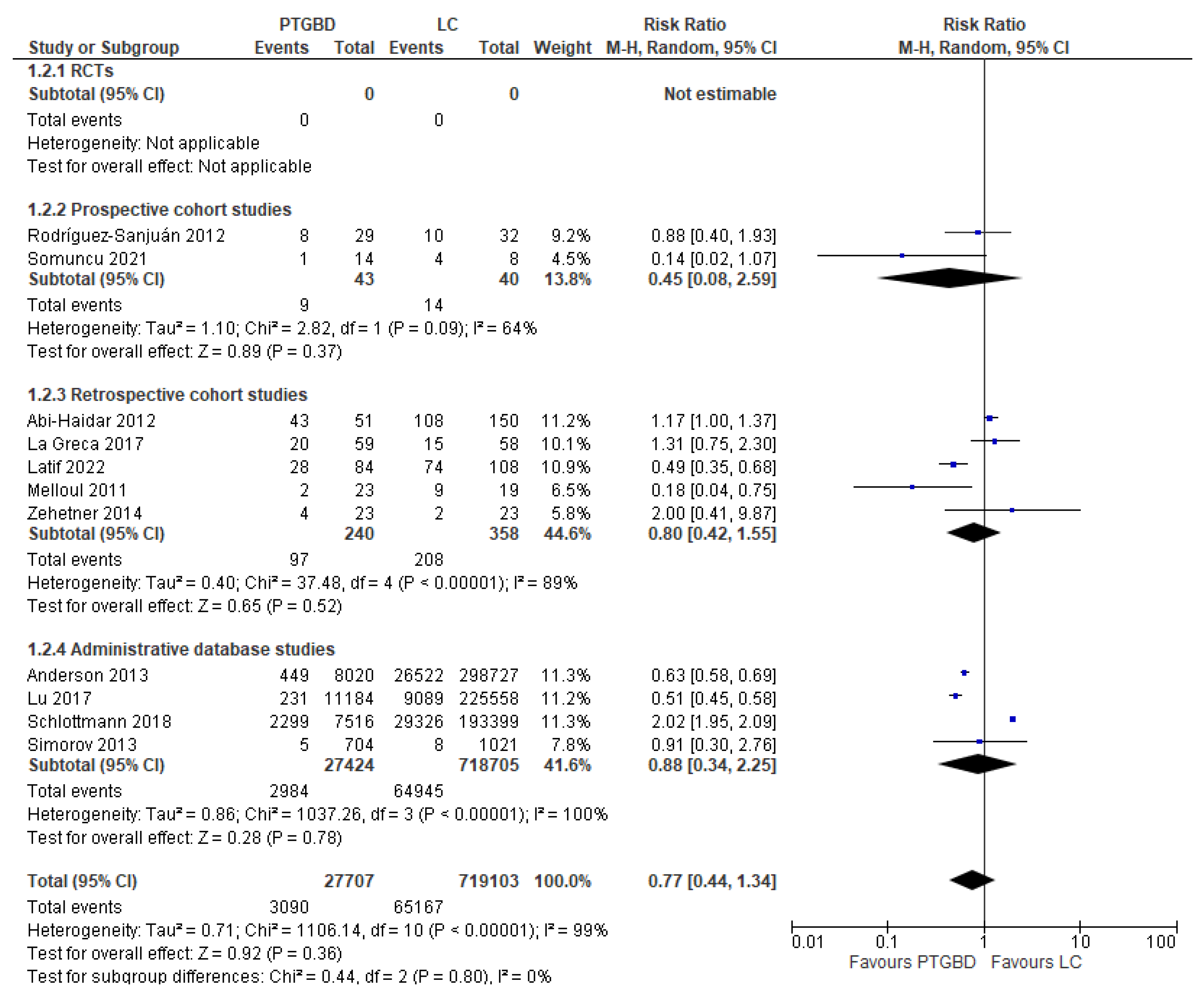

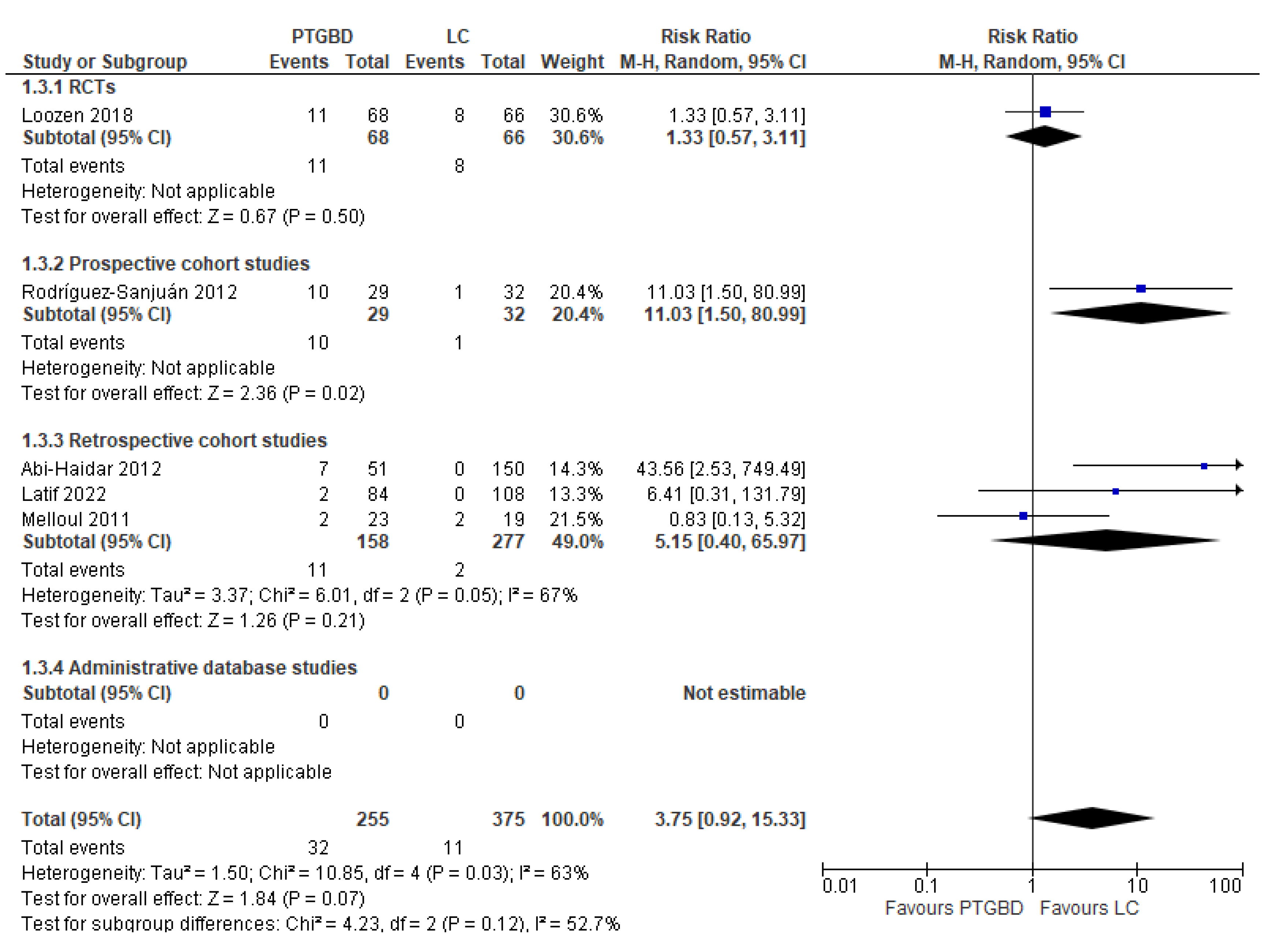

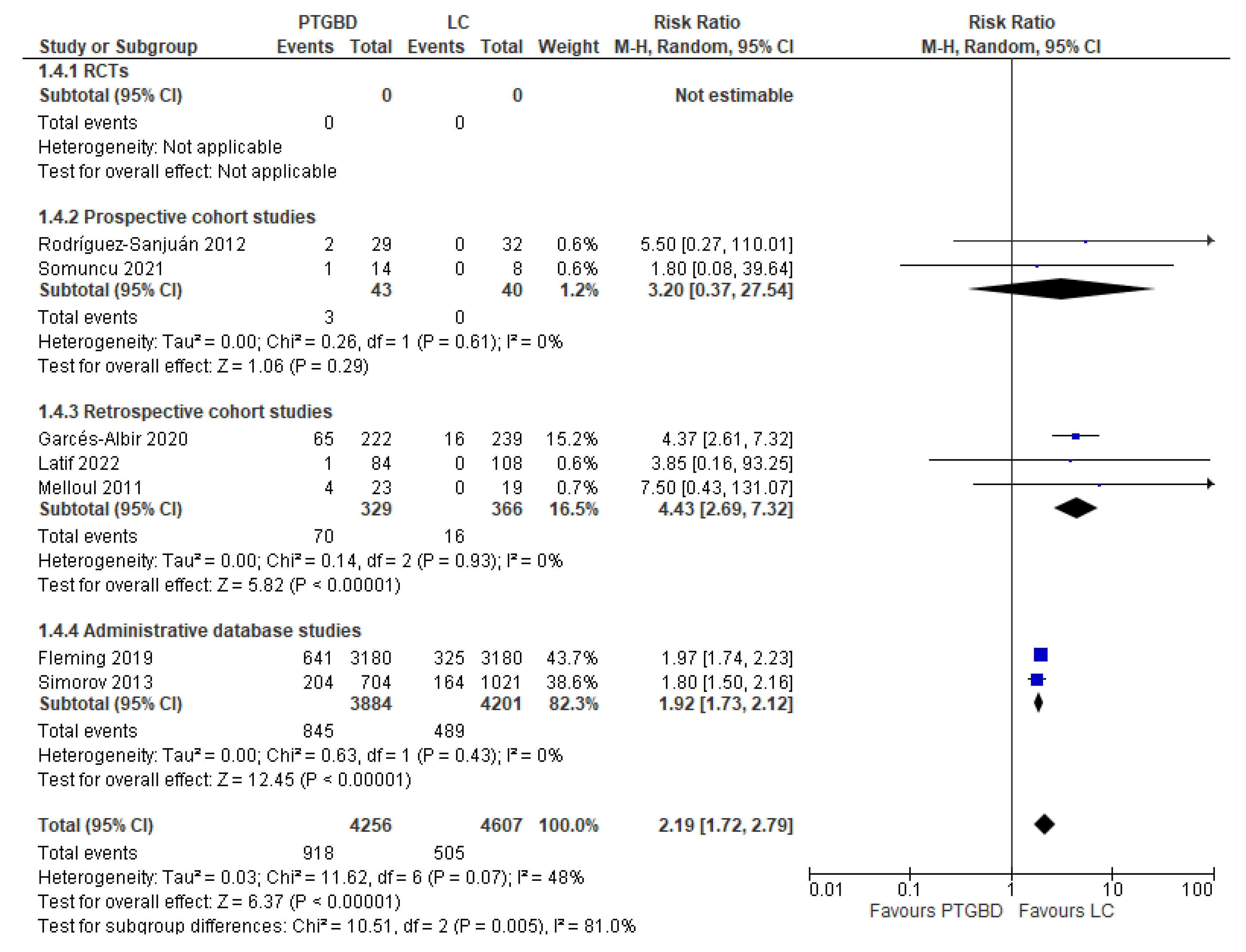

Analysis of results: Secondary outcomes

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Acknowledgments

References

- Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute Cholecystitis: A Review. JAMA. 2022; 327(10):965-975. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho GL, Lima DL, Shadduck PP, de Góes GHB, Alves de Carvalho GB, Cordeiro RN, Calheiros EMQ, Cavalcanti Dos Santos D. Which Cholecystectomy do Medical Students Prefer? JSLS. 2019; 23(1):e2018.00086 [CrossRef]

- Blum CA, Adams DB. Who did the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy? J Minim Access Surg. 2011; 7(3):165- 8. [CrossRef]

- McSherry CK. Cholecystectomy: the gold standard. Am J Surg. 1989; 158(3):174-8. [CrossRef]

- Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;(4):CD006231. [CrossRef]

- Ansaloni L, Pisano M, Coccolini F, et al. 2016 WSES guidelines on acute calculous cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016 Jun 14; 11:25. [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;30(6):CD005440. [CrossRef]

- Zhou MW, Gu XD, Xiang JB, Chen ZY. Comparison of clinical safety and outcomes of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis. Sci World J. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wu XD, Tian X, Liu MM, Wu L, Zhao S, Zhao L. Meta-analysis comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2015; 102:1302–1313. [CrossRef]

- Cao AM, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Early Cholecystectomy is superior to delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:848–857. [CrossRef]

- Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61. [CrossRef]

- Schuster KM, Holena DN, Salim A, Savage S, Crandall M. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma emergency general surgery guideline summaries 2018: acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, acute diverticulitis, acute pancreatitis, and small bowel obstruction. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2019; 4(1):e000281 [CrossRef]

- Elsharif M, Forouzanfar A, Oaikhinan K, Khetan N. Percutaneous cholecystostomy… why, when, what next? A systematic review of past decade. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018 Oct 5;100(8):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Stanek A, Dohan A, Barkun J, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: A simple bridge to surgery or an alternative option for the management of acute cholecystitis? Am J Surg. 2018 Sep;216(3):595-603. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018 Jan;25(1):55-72. [CrossRef]

- Malik A, Seretis C. Use of percutaneous cholecystostomy for complicated acute lithiasic cholecystitis: solving or deferring the problem? Pol Przegl Chir. 2021; 93(0):7-12. [CrossRef]

- Filiberto AC, Efron PA, Frantz A, Bihorac A, Upchurch GR Jr, Loftus TJ. Personalized decision-making for acute cholecystitis: Understanding surgeon judgment. Front Digit Health. 2022; 4:845453. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372: 71. [CrossRef]

- Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019 Aug 28;366:l4898. [CrossRef]

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

- Loozen CS, van Santvoort HC, van Duijvendijk P, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus percutaneous catheter drainage for acute cholecystitis in high risk patients (CHOCOLATE): multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018; 363:k3965. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sanjuán JC, Arruabarrena A, Sánchez-Moreno L, González-Sánchez F, Herrera LA, Gómez-Fleitas M. Acute cholecystitis in high surgical risk patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy or emergency cholecystectomy? Am J Surg. 2012; 204(1):54-9. [CrossRef]

- Somuncu E, Kara Y, Kızılkaya MC, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy instead of laparoscopy to treat acute cholecystitis during the COVID-19 pandemic period: single center experience. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2021; 27(1):89-94. [CrossRef]

- Abi-Haidar Y, Sanchez V, Williams SA, Itani KM. Revisiting percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis based on a 10-year experience. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):416-22. [CrossRef]

- El Hadidi A, Negm A, Halim MA, Basheer M, Samir M, Attia MS. Cholecystectomy versus percutaneous cholecystostomy drainage in critically ill patients with acute calculous syndrome: a comparative study. Egypt J Surg 2019; 38:46-5. [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Albir M, Martín-Gorgojo V, Perdomo R, et al. Acute cholecystitis in elderly and high-risk surgical patients: is percutaneous cholecystostomy preferable to emergency cholecystectomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2020; 24(11):2579-2586. [CrossRef]

- La Greca A, Di Grezia M, Magalini S, et al. Comparison of cholecystectomy and percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute cholecystitis: results of a retrospective study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017; 21(20): 4668-4674.

- Melloul E, Denys A, Demartines N, Calmes JM, Schäfer M. Percutaneous drainage versus emergency cholecystectomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis in critically ill patients: does it matter? World J Surg. 2011 Apr;35(4):826-33. [CrossRef]

- Zehetner J, Degnera E, Olasky J, Mason RA, Drangsholt S, Moazzez A, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis and failed conservative management: a matched-pair analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014; 24(6):523-7. [CrossRef]

- Latif J, Kushairi A, Thurley P, Bhatti I, Awan A. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus percutaneous cholecystostomy: suitability of APACHE-II Score, ASA Grade, and Tokyo Guidelines 18 Grade as predictors of outcome in patients with acute cholecystitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2022 Jun 1;32(3):342-349. [CrossRef]

- Smith TJ, Manske JG, Mathiason MA, Kallies KJ, Kothari SN. Changing trends and outcomes in the use of percutaneous cholecystostomy tubes for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 2013; 257(6):1112-5. [CrossRef]

- Anderson JE, Chang DC, Talamini MA. A nationwide examination of outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy compared with cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, 1998-2010. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27(9):3406-11 [CrossRef]

- Anderson JE, Inui T, Talamini MA, Chang DC. Cholecystostomy offers no survival benefit in patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis and severe sepsis and shock. J Surg Res. 2014; 190(2):517-21. [CrossRef]

- Fleming MM, DeWane MP, Luo J, Liu F, Zhang Y, Pei KY. A propensity score matched comparison of readmissions and cost of laparoscopic cholecystectomy vs percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2019; 217(1):83-89.

- Schlottmann F, Gaber C, Strassle PD, Patti MG, Charles AG. Cholecystectomy vs. cholecystostomy for the management of acute cholecystitis in elderly patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 Mar;23(3):503-509. [CrossRef]

- Simorov A, Ranade A, Parcells J, Shaligram A, Shostrom V, Boilesen E, Goede M, Oleynikov D. Emergent cholecystostomy is superior to open cholecystectomy in extremely ill patients with acalculous cholecystitis: a large multicenter outcome study. Am J Surg. 2013 Dec;206(6):935-40. [CrossRef]

- Lu P, Chan CL, Yang NP, Chang NT, Lin KB, Lai KR. Outcome comparison between percutaneous cholecystostomy and cholecystectomy: a 10-year population-based analysis. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):130. [CrossRef]

- Griniatsos J, Petrou A, Pappas P, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy without interval cholecystectomy as definitive treatment of acute cholecystitis in elderly and critically ill patients. South Med J 2008; 101:586-90. [CrossRef]

- McKay A, Abulfaraj M, Lipschitz J. Short- and long-term outcomes following percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients. Surg Endosc 2012; 26:1343-51. [CrossRef]

- 40. Horn T, Christensen SD, KirkegaÃärd J, Larsen LP, Knudsen AR, Mortensen FV. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective treatment option for acute calculous cholecystitis: a 10-year experience. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17:326-31. [CrossRef]

- Zerem E, Omerovic S. Can percutaneous cholecystostomy be a defnitive management for acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2014; 24:187–191. [CrossRef]

- Chang YR, Ahn YJ, Jang JY, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis in patients with high comorbidity and re-evaluation of treatment efficacy. Surgery 2014 155:615–622. [CrossRef]

- hok KS, Chu FS, Cheung TT, et al. Results of percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy for high surgical risk patients with acute cholecystitis. ANZ J Surg 2010; 80:280-3. [CrossRef]

- 44. Boules M, Haskins IN, Farias-Kovac M, et al. What is the fate of the cholecystostomy tube following percutaneous cholecystostomy? Surg Endosc 2017; 31:1707–1712. [CrossRef]

- Loftus TJ, Collins EM, Dessaigne CG, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: prognostic factors and comparison to cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2017; 31:4568–4575. [CrossRef]

- Hall BR, Armijo PR, Krause C, Burnett T, Oleynikov D. Emergent cholecystectomy is superior to percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement in critically ill patients with emergent calculous cholecystitis. Am J Surg 2018; 216:116–119. [CrossRef]

- Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J, Sandström P. Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford) 2009; 11(3):183–93. [CrossRef]

- McArthur P, Cuschieri A, Shields R, et al. Controlled clinical trial comparing early with interval cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Proc R Soc Med 1975; 68:676–678.

- Norrby S, Herlin P, Holmin T, et al. Early or delayed cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis? A clinical trial. Br J Surg 1983; 70:163–165. [CrossRef]

- Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Fukui T. Early versus delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Today 2005; 35:553–560. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui T, MacDonald A, Chong PS, et al. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Surg 2008; 195:40–47. [CrossRef]

- Jia B, Liu K, Tan L, Jin Z, Liu Y. Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage combined with laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute complicated cholecystitis: comparison of curative efficacy. Am Surg 2018; 84:438–442.

- Riall TS, Zhang D, Townsend CM Jr, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Failure to perform cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in elderly patients is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and cost. J Am Coll Surg. 2010; 210(5): 668-77. [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi R, Cozza V, Sapienza P, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy as bridge to surgery vs surgery in unfit patients with acute calculous cholecystitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2022: S1479-666X(22)00138-X. [CrossRef]

- Granlund A, Karlson BM, Elvin A, Rasmussen I. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2001; 386:212-7. [CrossRef]

- Leveau P, Andersson E, Carlgren I, Willner J, Andersson R. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: a bridge to surgery or definite management of acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients? Scand J Gastroenterol 2008; 43:593-6 [CrossRef]

| Author and year of publication | Nation | Type of study | N. of patients included | Time of enrolment | PTGBD group | LC in control group | OC | NR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of patients | Timing | N. of patients | Timing | N. of patients | Timing | N. of patients | |||||

| Latif et al. 2022 |

United Kingdom | RCS | 192 | 2016 to 2018 | 84 | NR | 108 | After >48 of conservative management | 0 | NR | 0 |

| Somuncu et al. 2021 | Turkey | PCS | 22 | March 2020 to June 2020 | 14 | NR | 8 | NR | 0 | NR | 0 |

| Garcés Albir et al. 2020 | Spain-Uruguay | RCS | 461 | January 2005 to December 2016 | 222 | NR | 239 | NR | 0 | NR | 0 |

| El Hadidi et al. 2019 | Egypt | RCS | 225 | February 2014 a September 2017 | 65 | NR | 83 | NR | 77 | NR | 0 |

| Fleming et al. 2019 | USA | Administrative database studies | 6360 | 2013 to 2014 | 3180 | NR | 3180 | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Loozen et al. 2018 | Netherlands | RCT | 134 | February 2011 to January 2016 | 68 | Within 24h after randomization | 66 | Within 24h after randomization | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Schlottmann et al. 2018 | USA- Argentina | Administrative database studies | 200915 | January 2000 to December 2014 | 7516 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 193399 |

| La Greca et al. 2017 | Italy | RCS | 646 | August 2009 to March 2016 | 90 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 556 |

| Lu et al. 2017 |

Taiwan | Administrative database studies | 236742 | 2003 to 2012 | 11184 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 225558 |

| Anderson et al. 2014 | USA | Administrative database studies | 28724 | 1995 to 2009 | 1218 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 27506 |

| Zehetner et al. 2014 | USA | RCS | 46 | January 1999 to October 2010 | 23 | NR Presence of symptoms for 72h |

23 | NR Presence of symptoms for 72h |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anderson et al. 2013 | USA | Administrative database studies | 306747 | 1998 to 2010 | 8020 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 298727 |

| Simorov et al. 2013 | USA | Administrative database studies | 1725 | October 2007 to June 2011 | 704 | NR | 822 | NR | 199 | NR | 0 |

| Smith et al. 2013 |

USA | RCS | 432 | April 1998 to December 2009 | 143 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 286 |

| Abi-Haidar et al. 2012 | USA | RCS | 201 | January 2001 to December 2010 | 51 | NR | 110 | During 24h of admission = 32 Later than 24h after admission = 33 Elective procedure = 45 |

40 | During 24h of admission = 26Later than 24h after admission = 7 Elective procedure = 3 Emergency procedure after discharged = 4 |

0 |

| Rodrìguez-Sanjuàn et al. 2012 | Spain | PCS | 61 | January 2005 to December 2010 | 29 | NR | 14 | First 72hours from AC onset | 18 | First 72hours from AC onset | 0 |

| Melloul et al. 2011 | Switzerland | RCS | 42 | 2001 to 2007 | 23 | 12-24h | 10 | 12-24h | 9 | 12-24h | 0 |

| Total | 783.672 | 32.634 | 4.663 | 343 | 746.032 | ||||||

| Transhepatic route | Transperitoneal route | Not Reported |

|---|---|---|

| Latif et al. 2022 | Loozen et al. 2018 | Fleming et al. 2019 |

| Somuncu et al. 2021 | La Greca et al. 2017 | Schlottmann et al. 2018 |

| Garcés Albir et al. 2020 | Smith et al. 2013 | Lu et al. 2017 |

| El Hadidi et al. 2019 | Anderson et al. 2014 | |

| Loozen et al. 2018 | Zehetner et al. 2014 | |

| Melloul et al. 2011 | Anderson et al. 2013 | |

| Abi-Haidar et al. 2012 | Simorov et al. 2013 | |

| Rodriguez-Sanjuàn et al. 2012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).