Introduction

Falls during hospitalization have been estimated to occur in 700,000 to 1 million individuals in the United States annually which equate to three to five falls for every 1000 bed-days [

1,

2]. One in three inpatient falls result in injuries which are exacerbated by pre-existing healthcare issues [

3,

4]. The consequences of inpatient falls are prolonged length-of-stay, increased financial cost, injuries, reduced quality of life, fear of falling, anxiety, and reduced physical activity. Some falls in hospital are potentially avoidable, with potentially modifiable intrinsic (related to the individual) and extrinsic (environmental) risk factors [

5]. The interaction between unfamiliar hospital environments and the presence of acute illness further amplifies the risk for falls during hospitalization [

6,

7].

Previous studies have identified many factors which increase the risk of falls in hospital, including anaemia [

8], delirium [

9], balance impairment [

10], osteoporosis, muscle weakness [

10], medications [

11,

12], history of falls [

13], advanced age and environmental hazards [

14]. A combination of factors are expected to occur within the same individual as those hospitalized are often older with multiple medical issues. The identification of the above risk factors has been used for decades within the fall risk assessments process with the use of assessment tools and scores now common place [

15]. However, most such instruments are not sufficiently sensitive in predicting falls and inevitably focuses attention on the small number of patients at high risk of falling, with falls then occurring among those deemed at low risk. The recently released World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management for Older Adults 2022, therefore, recommend that all older patients should be regarded as a high-risk population, and advocates against the use of risk assessment tools [

16].

Evidence on effective fall prevention strategies in hospitals, however, is limited to interventions such as high-risk wristbands, bed signage and medication review, with other interventions having limited success in reducing falls in hospital [

15]. A previous review has suggested that multifactorial assessments targeting mobility, toileting, delirium and orthostatic blood pressure with appropriate interventions may reduce falls in hospital by 20-30%. Similarly, extrinsic risk factors can be addressed by providing mobility aids, pictorial signage and hearing aids [

16].

The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) is a multifaceted approach, established in 2001 by John Hopkins Hospital with the support of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), to identify and eliminate patient safety hazards, and improve local safety culture through a validated, structured framework [

17]. The CUSP model values frontline staff and teams and emphasizes the need for organizational support to address deficits in patient safety practices. The program can be conducted “anywhere”, on “anything” and by “anyone” within the healthcare establishment, as it represents a flexible approach towards risks and is designed to target work at unit levels. This is achieved through the engagement and empowerment of hospital staff. Elements such as integrated teamwork, communication, and engaging senior executives for the improvement in patient safety culture are emphasized within the model [

18,

19,

20]. The aim of this study was to describe the implementation process of a CUSP intervention for the prevention of falls in hospital, as well as to evaluate the effect of such a program on patient safety culture within the intervention unit.

Methods

Overview

A quality improvement study was conducted using the implementation research framework established by the World Health Organization Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research [

21]. The impact and effectiveness of the uncontrolled intervention was determined using both traditional outcomes as well as an evaluation process guided by the UK Medical Research Council process evaluation framework [

22]. In this study, the three phases: pre-implementation, implementation, and sustainment of CUSP, were evaluated. During the pre-implementation phase, training was provided within the one-month run-in phase, then the implementation phase ran for 24 months, and the sustainment phase was considered the two months immediately after the implementation phase at the end of which an evaluation activity was carried out.

Setting

The study was conducted within an acute medical ward at a teaching hospital in Kuala Lumpur. The selected ward contained a total of 21 beds, which housed an average of 600 adult hematology inpatients annually. Treatments commonly delivered within the ward included cancer chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation and cancer progression care. In addition to 16 general beds, there were five ring-fenced beds for bone marrow transplantation. The nurse to patient ratio was 1:5. The sample population comprised HCPs, including doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, and clinical support staff, from the selected ward.

Program Implementation

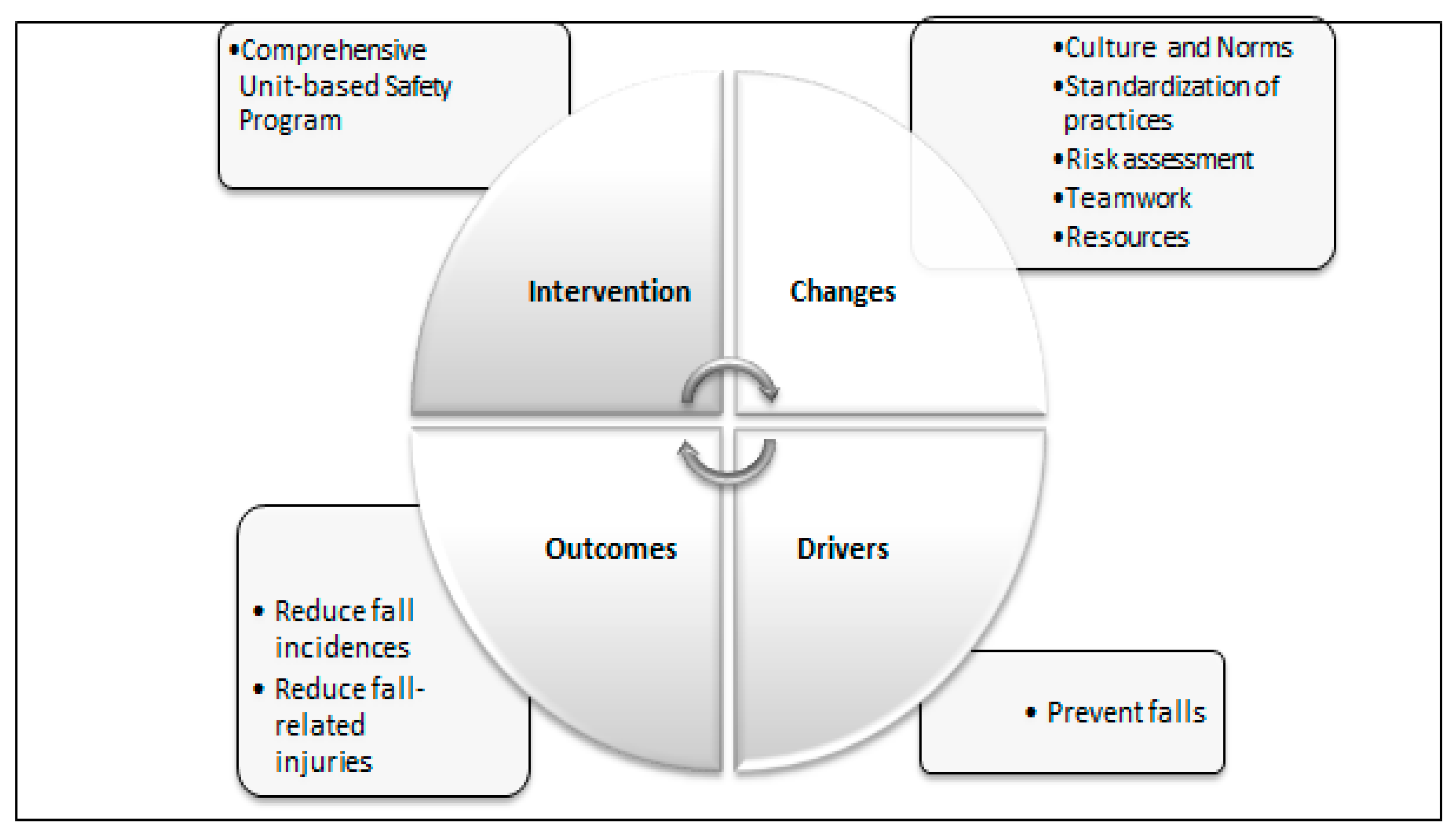

In this study, CUSP toolkits and modules were implemented as a quality improvement intervention using the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle (

Figure 1). Following the formation of the CUSP team, a brainstorming meeting was held during which safety issues with particular attention towards safety culture and norms, practices, assessment, and resources were highlighted. The drivers for fall prevention were then identified in a series of meetings with senior executive engagement and the support of management. Appropriate outcome measures to evaluate the CUSP intervention were also identified during these meetings.

A graphical presentation of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program intervention plan-do-study-act cycle. Key areas addressed in each section are mentioned in the bullet points within the textboxes aligned to the segment to provide an outline of ‘Changes’ (Plan), ‘Drivers’ (Do), ‘Outcomes’(Study), ‘Intervention’ (Act).

Quality Improvement Process

The quality improvement framework from the Johns Hopkins University Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality was adopted to develop a five-step quality improvement process. The first step of the CUSP process involved education on the science of safety. An in-depth description of safety elements in a hospital was provided, with a particular focus on systems. Local issues pertaining to the ward of interest were then identified. The deficiencies to be addressed were then prioritized as the second step of the intervention. The third step involved bridging the gap between management and HCPs, which required partnership with senior executives and hospital leaders in acknowledging the importance of addressing the safety hazards concerned and providing resources. The AHRQ tools were then introduced to all hospital ward staff as the fourth step of the intervention so that they could understand and learn from the deficits. The fifth and final step involved implementation of tools to enhance teamwork and communication.

Team Members’ Roles and Responsibilities

The CUSP intervention team involved the recruitment of interdisciplinary members comprising physicians, nurses, quality improvement officers, physiotherapists, and support staff, with additional input from senior executives, a physician champion, patient safety officers, nurse manager, and frontline staff. Staff members were given specific responsibilities to deliver the program using education, awareness, and intervention toolkits [

23,

24] (

Table 1).

Training Modules

The training provided to the CUSP team included an online training module, which was distributed to the team. The online training module was delivered in eight modules through the Schoology® online learning platform (Power School, California, USA), utilizing material created by AHRQ.

Table 2 Provides an outline of the content delivered during each of the eight modules.

Patient Safety Checklist

A daily safety culture checklist was used by the CUSP team during ward rounds to review patients identified as high risk by HCP. The checklist also served as a tool to improve communication between team members, patients, and family members. The content validity of the checklist, which had been modified from the original AHRQ framework, was determined by an interdisciplinary expert panel which included the hospital falls committee, physicians and patient safety officers [

24].

Team Meetings and Audit Measures

Monthly meetings were conducted among the CUSP team members while quarterly meetings occurred between the CUSP team and quality coordinators to discuss the barriers and potential solutions towards improving staff safety culture and reducing falls. Minutes for all meetings and discussions were recorded by the nurse manager for audit purposes and to track improvement activities. During these meetings, the CUSP teams reviewed monthly ward falls data, devised improvement activities and evaluated outcomes of each improvement activity. The researcher gathered data on fall events obtained from the hospital electronic incident reporting system which held a customized template specifically to record fall occurrences, associated injuries and actions taken, developed by the hospital falls prevention committee.

Safety Rounds

Dedicated safety rounds were conducted by the CUSP team with a morning briefing tool in addition to the daily safety culture checklist for all patients tagged as high risk. The morning briefing tool identified problems that occurred during the night or potential problems for the day. This helped create dialogues to promote effective communication using concise and relevant information before the commencement of ward rounds. The briefing process would start with updates on patients and tools completed by the charge nurse daily. Based on the daily safety culture checklist, risk factors and plans were documented and executed to evaluate the effectiveness of assessment. The CUSP team extracted information from existing hospital information systems (e.g electronic medical records) to fill in the checklist for documentation and monitoring. Upon completion of ward rounds, decisions were conveyed to the nurse-in-charge who was tasked with the responsibility of record-keeping for continuous monitoring and documentation. During the rounds bilingual pamphlets and videos which had been prepared by the CUSP team, and approved by the hospital public information department, were distribution.

Process Evaluation

The context of the process evaluation was to identify influencing factors on the level or success of the implementation of the intervention. The dose delivered included the education module, safety rounds as well as team and management meetings held. Dose received was determined as the extent of engagement of the CUSP team in terms of participation in training, safety rounds and meetings. Fidelity was monitored by recording the number of rounds and number of HCPs who attended the rounds over time as well as actions taken after rounds. The target audience was hence managers, leaders and policy makers who will enable the replication of such an intervention and generalization of the knowledge to other areas of patient safety.

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome

The Safety Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ) [

25] is a 36-item tool that measures staffs attitude towards safety using a 5-point Likert type scale. The study instrument was administered virtually through Google Forms

TM (Google LLC, Mountainview, California, USA) pre- and post-intervention. The questionnaire was made available in both the English and Bahasa Melayu languages. The six domains of patient safety which comprised teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management, stress recognition, and working conditions were evaluated using the SAQ. Domain scores were calculated as percentage scores, with response scores of greater than 60% considered a satisfactory level of safety culture. The SAQ was first completed at baseline and at the end of the 24-month intervention period. The baseline SAQ results also helped identify potential areas for change.

Secondary Outcomes

Fall events which occurred in the intervention ward were considered the secondary outcomes. Retrospective hospital data on fall events prior to the intervention period had seen an increasing trend, leading to the assignment of a Hospital Quality Officer to introduce the CUSP intervention. All fall occurrences were recorded through the hospital incident reporting system which captured the total number of falls and injurious falls recorded. Reports on fall were retrieved from the incident reporting system using the formula determined by Malaysian Patient Safety Council, and tabulated within the monthly reports submitted to hospital management [

26]. Fall rates were, therefore, determined as number of falls per 1,000 consecutive hospital days of patients admitted and discharged for the six months prior to the introduction of CUSP and for a further 24 months from the commencement of the CUSP intervention.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science Version 21 (IBMTM, Armonk, USA). Results were displayed using frequency distributions and measures of central tendency. SAQ scores were calculated and aggregated to yield a mean score for respective SAQ domains. Actual fall occurrence and safety round attendance and frequency were presented as run charts. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

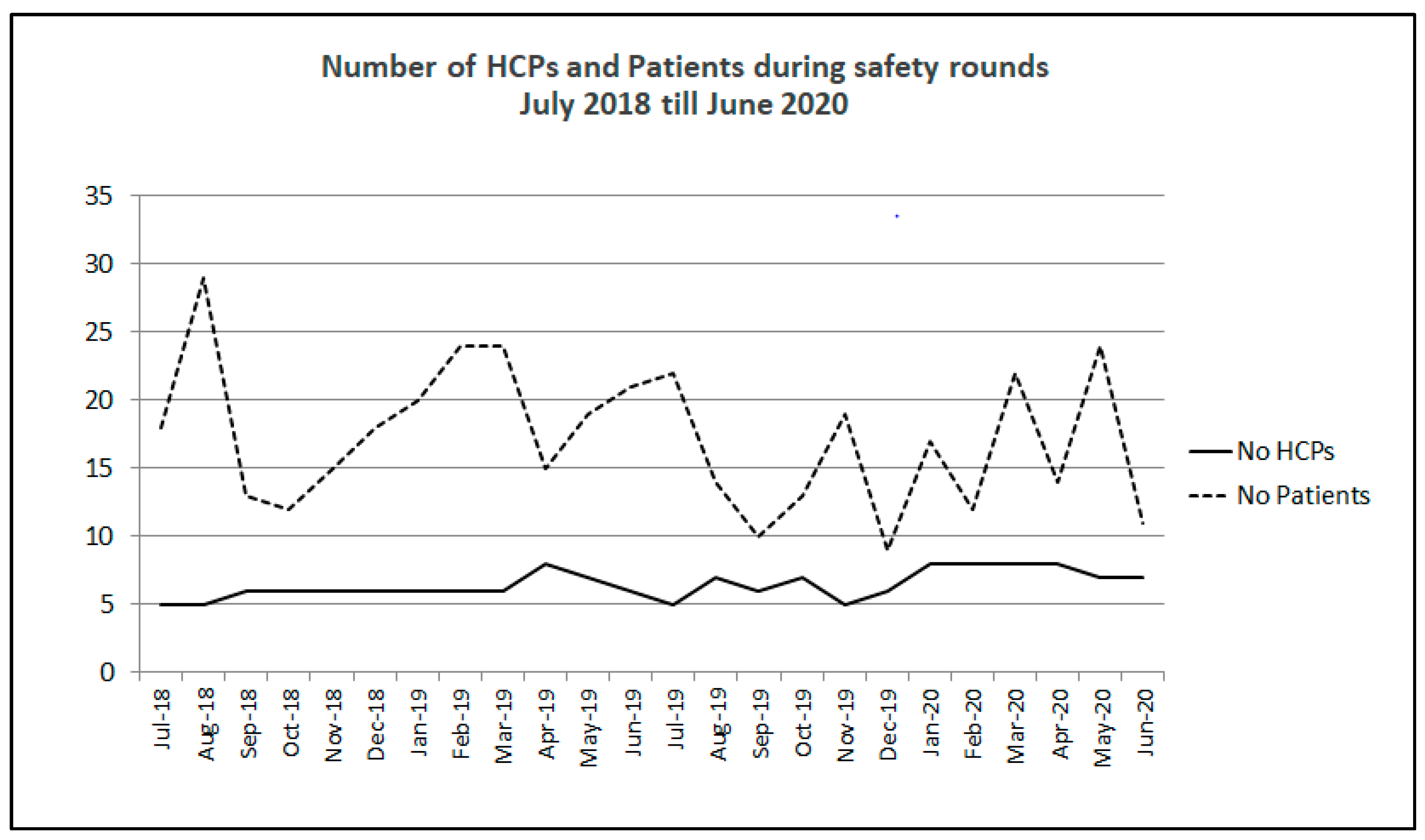

Weekly rounds were conducted throughout the two-year period.

Figure 2 shows the mean number of HCPs attending weekly rounds per month and the average number of patients reviewed throughout the two years. At the beginning of the intervention, five HCPs would attend weekly rounds, and by the end of the two-year implementation period, weekly rounds were attended by seven to eight HCP. The number of patients reviewed per month ranged from nine to 29. The total number of patients monthly dipped to a minimum of nine in October 2019, but this has increased again in 2020, suggesting a sustained number of patients being reviewed each month.

Risk Factors and Actions Taken

Table 3 displays the number safety rounds conducted each month and the monthly total in frequency each risk factor was identified, plans were made and actions taken during safety rounds by month. Most risk factors, plans and actions were administered in all patients seen during safety rounds, apart from peri-surgical or peri-procedural risks and blood transfusions, which were only present or required in some cases.

CUSP Team Meeting

The issues identified and discussed in the monthly CUSP team and quarterly management meetings are tabulated according to patient, staffing , environmental, and administrative factors in

Table 4. Patient-related factors discussed in the meetings including intrinsic factors such as age, clinical factors, mobility, nutrition, and cognition. Extrinsic factors such as medications and treatment plans and improper footwear were also listed. Language barrier and reluctance to call for assistance, with specific reference to male patients were also highlighted as patient-related factors. Those with falls risk increasing drugs received medication reviews, while nutrition factors were then addressed by the dietitian who would recommend fortified diets and nutritional supplementation. The reluctance to seek assistance despite being informed during ward orientation was addressed with additional education materials and regular reminders.

The issue of inadequate staffing levels was brought up to the nursing management to support the need for additional nursing assistants particularly during night shifts. New nurses were provided with an additional session of education and orientation on the program to enhance their knowledge on the science of safety and to inform them of the objectives of CUSP team activities. Another important factor was the shortage of adequately trained cleaning staff. They encountered lack of manpower which led to the employment of foreign workers who lacked fluency in local languages, leading to an increase in the potential hazards of wet floors particularly in toilets and at patients’ bedsides. The supervisors of the cleaning services were invited for a meeting to engage them on the importance of their roles in ensuring patient safety.

Environmental factors, such as uneven flooring within toilets, were highlighted to the engineering department. Improvements were also made to toilet floors by ensuring that the water flowed away from the toilet entrance. Engineering issues were solved with the assistance of the quality officer and senior executive communicating with higher management. The CUSP team proposed adjustable or ultra-low beds alongside the hospital falls prevention committee for patients with cognitive impairment at risk of falling from the bed.

Outcomes

Safety Attitude Questionnaire

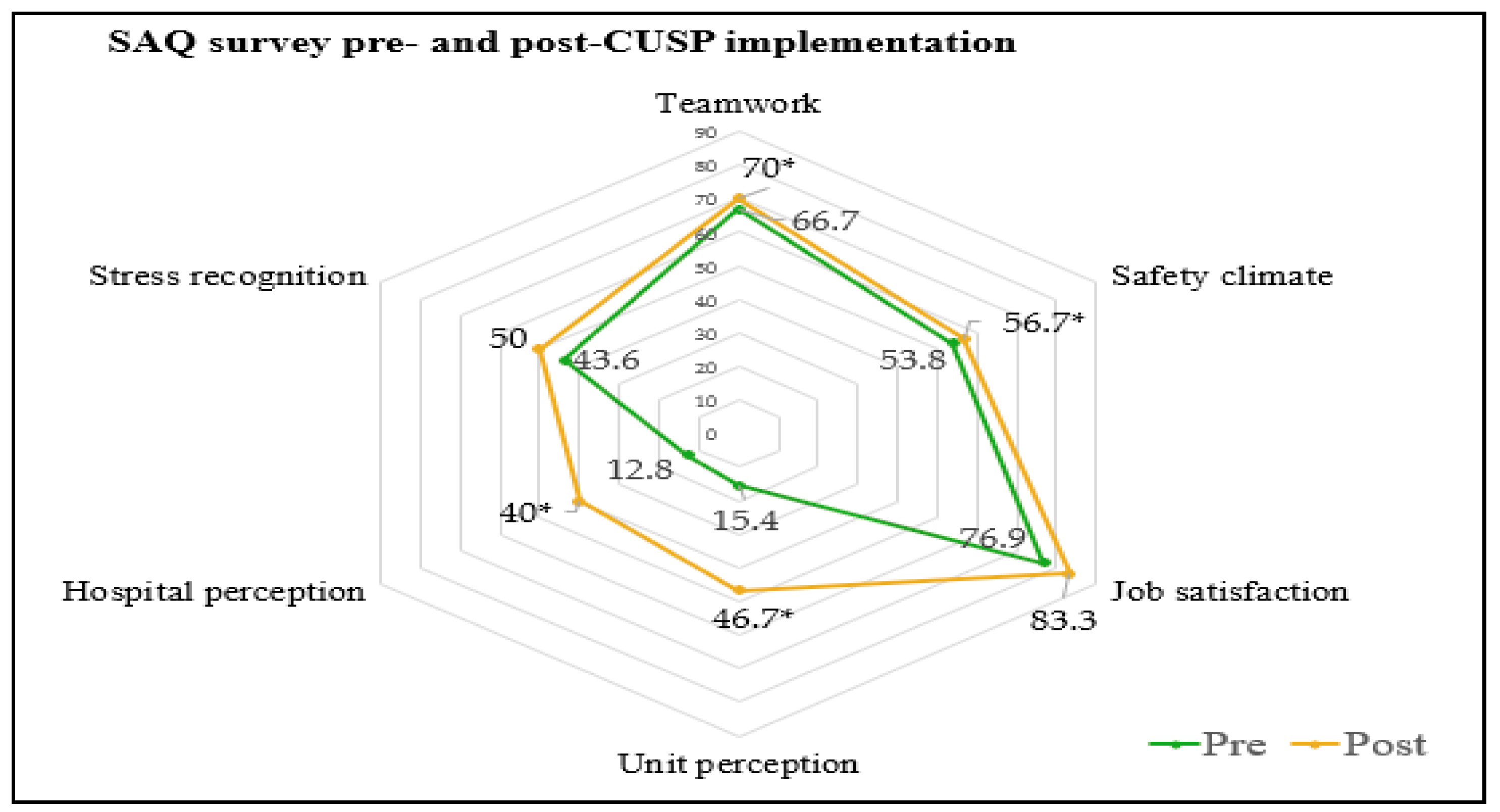

The Safety Attitude Questionnaire was administered among HCPs before and after the two-year intervention period. Among the 39 HCPs evaluated in pre-intervention assessments, 35 (87.5%) were female, 64.4% were nurses and 28 (71.8%) had less than 10 years of experience. The post-intervention survey included 30 HCPs, 27 (90%) females with 22 (73.3%) with less than 10 years’ of experience. There were significant improvements in all domains, except for job satisfaction and stress recognition. The results obtained are summarized in Figure 5.

Overall positive perception in TW, SC, JS, SR, UP, HP and WC were 66.7, 53.8, 76.9, 17.9, 15.4, 12.8 and 43.6 respectively during pre-intervention assessments. While positive perceptions were observed within TW, SC, JS, SR, UP, UH, and WC were 70.0, 56.7, 83.3, 30.0, 46.7, 40.0, and 50.0 respectively during post-intervention assessments (

Figure 3).

Fall Outcomes

The intervention was not powered to determine differences in fall outcomes. A description of total falls and fall rates were therefore offered with no hypothesis testing. Prior to the implementation of safety rounds, falls rate was 11.18 per 1,000 patient bed days. The falls rate reduced to 8.2 per 1,000 bed days by 2018, 6.5 per 1,000 bed days by 2019 and dropped further to zero at the end of the intervention period with the unit observing 365 fall-free days in 2020 (

Table 5). The total number of falls observed throughout the study period was seven, with five falls in 2018, four falls in 2019 and zero falls in 2020. Changes observed in key performance indicators and run charts were submitted to hospital management and the Malaysian Patient Safety Council quarterly as an audit measure.

Discussion

A Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Intervention Program enhanced patient safety culture with an observed reduction in falls over a two-year period. Improvements in teamwork, safety culture, unit perception, hospital perception and working condition were detected using the SAQ. The intervention was sustained over the two-year period with an increasing number of HCP attending weekly safety rounds and an increasing number of safety interventions administered over time.

Falls have been made the major area of focus for CUSP in this study due to the negative impact it has on the patient’s quality of life and cost of hospitalization [

27]. The cornerstone of this intervention was to sustainably implement CUSP in a clinical area with front-line staff involvement to enhance the culture of safety in the unit, leading to measurable improvements in safety culture and falls outcomes. CUSP and SAQ provide staff with opportunities to assess their own infrastructure and working environment while identifying errors and engaging leaders for systemic improvement. Education on the science of safety enhanced staff ability to focus on system factors related to safety that led to significantly improved teamwork and communication among HCPs. A previous study

suggested that accountability on patient care, commitment, leadership and continuous integration of safety culture education, enhances the sustainability of patient safety initiatives among HCPs [

28]

.

Safety rounds were found to be sustainable over a two-year period, with several team members remaining constant throughout while the number of interventions per round increased over time despite other studies reporting difficulties with adherence and sustainability [

29]. Fluctuations in the number of HCPs attending the rounds could be attributed to festive holiday seasons and examinations as the study was based in a teaching hospital. Over the intervention period, issues discussed during the safety rounds evolved from events related to individual patients, to engagement of patient and family, teamwork, through to environmental and systemic issues. Communication between the team and senior executives meant team members had a mechanism through which to address multidisciplinary issues related to patients and staff. In this increasingly complex healthcare system, it is important to have a platform to discuss and resolve safety concerns.

The enhanced knowledge, teamwork and communication observed in our study has also been demonstrated in a previous study by the National Health Services Sustainability Model with positive impact on tackling barriers to successful implementation [

29]

. Sustainability is defined as making an innovation routine with two conditions: institutionalization and routinization. Providing the resources and conditions needed for a new practice is institutionalization and the process of the new practice becoming a routine activity within the organization is referred to as routinization [

30]

. Top management support and the resources delivered led to institutionalization of the activities and with teamwork and communication, the new practices became a routine activity. Communication with mutual learning is considered the key to optimal patient safety, especially when multi-professional collaboration is required [

31]. The safety culture of HCPs within this study was successfully altered to include new norms in work processes. Specific improvements were observed in terms of stress recognition, unit perception and hospital perception post CUSP implementation. Studies have reported poor communication to be a major factor leading to adverse events in hospitals [

32]. Hence, interdisciplinary collaborations, as demonstrated in this study, plays a pivotal role in the safe delivery of care within a medical ward.

Apart from encouraging behaviour change, leadership also plays an important element in the provision of continuous support for culture change [

33]. Scheduled meetings and discussions, formal and informal, with senior executives and higher management have encouraged the team to absorb safety rounds as part of ward routine activities. Interdisciplinary rounds with active discussion of fall assessment prompt intervention, and prevention, increased safety awareness among team members with specified roles. Ward staff took ownership of its fall rates and mandated a standardized flow of work to ensure patient safety. This led to a drastic drop in fall rates in the ward. The momentum to change the safety culture of the ward came after the success of attaining zero falls, which motivated team members to believe that culture can be changed.

There were possible cost-savings repercussions, as preventing falls has reduced the length of stay of patients, prevented fall-related injuries, and litigation. Findings from this study correspond with a study conducted within an interventional radiology setting, which revealed that integrating safety education promotes error reporting and improves safety culture [

34]. Improvements in fall rates in this study evidenced the success of a safety program anchored on multidisciplinary engagements and integration of evidence-based methodologies. Our findings were similar with an observational study on the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary quality improvement (QI) activity to decrease fall rates and increase staff conformance in the QI approaches [

35,

36].

This study was limited by its sample size and involvement of only from one medical ward with no control ward used. As such, results can only be interpreted as descriptive data. Future studies should consider a multi-centre cluster randomized approach. This study also did not take into accountfall-related injuries amongst other safety issues, due to the limited number of fall occurrences as injurious falls are more likely to prolong hospital stay, quality of life, and hospital cost, while just reducing the number of falls may have the unintended effect of reducing mobilization within the ward with adverse consequences of acute deconditioning. Future research should also consider evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of CUSP intervention for other safety issues in reducing risk and harm.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the implementation of CUSP positively influenced patient safety culture with observed reduction in fall occurrence, similar to a study focused on engagement of all level of staff in implementation of multifaceted initiatives and consistent measurement of safety culture [38]. Process evaluation revealed a high level of fidelity and sustainability throughout the two-year intervention period. Future studies should consider an adequately powered controlled trial to determine the effects of CUSP intervention on actual falls outcomes.

Author Contributions

The study, monitoring of process and data collection tools were designed by KK, MPT MIZ. CK, MPT and KK assisted with data analysis. MPT MIZ and KK contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved University Malaya Medical Centre Ethics Committee (ID:2018921-6702). This study complied with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincerest gratitude to the management of University of Malaya Medical Centre, University of Malaya, John Hopkins Hospital, and all respondents for providing the necessary support to carry out this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, and authorship.

References

- LeLaurin, J. H., & Shorr, R. I. (2019). Preventing falls in hospitalized patients: state of the science. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 35(2), 273-283.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/falls.

- Janakiraman, B., Temesgen, M. H., Jember, G., Gelaw, A. Y., Gebremeskel, B. F., Ravichandran, H.,... & Belay, M. (2019). Falls among community-dwelling older adults in Ethiopia; A preliminary cross-sectional study. PLoS one, 14(9), e0221875.

- Stenvall, M., Olofsson, B., Lundström, M., Svensson, O., Nyberg, L., & Gustafson, Y. (2006). Inpatient falls and injuries in older patients treated for femoral neck fracture. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 43(3), 389-399.

- Bueno-Cavanillas, A., Padilla-Ruiz, F., Jiménez-Moléon, J. J., Peinado-Alonso, C. A., & Gálvez-Vargas, R. (2000). Risk factors in falls among the elderly according to extrinsic and intrinsic precipitating causes. European journal of epidemiology, 16, 849-859.

- Lakatos, B. E., Capasso, V., Mitchell, M. T., Kilroy, S. M., Lussier-Cushing, M., Sumner, L.,... & Stern, T. A. (2009). Falls in the general hospital: association with delirium, advanced age, and specific surgical procedures. Psychosomatics, 50(3), 218-226.

- Montero-Odasso, M., van der Velde, N., Martin, F. C., Petrovic, M., Tan, M. P., Ryg, J.,... & Masud, T. (2022). World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age and ageing, 51(9), afac205.

- Duh, M. S. , Mody, S. H., Lefebvre, P., Woodman, R. C., Buteau, S., & Viech, C. T. (2008). Anaemia and the risk of injurious falls in a community-dwelling elderly population. Drugs & aging, 25, 325-334.

- Mazur, K., Wilczyński, K., & Szewieczek, J. (2016). Geriatric falls in the context of a hospital fall prevention program: delirium, low body mass index, and other risk factors. Clinical interventions in aging, 1253-1261.

- Lipardo, D. S., & Tsang, W. W. (2020). Effects of combined physical and cognitive training on fall prevention and risk reduction in older persons with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled study. Clinical rehabilitation, 34(6), 773-782.

- Sivanandy, P., Krishnasamy, K., Maw Pin T. (2019). Medications Related Fall Incidents among Older Adults at a Teaching Hospital. Age and Ageing, Volume 48, Issue Supplement_4. [CrossRef]

- Sivanandy, P., Maw Pin Tan., Krishnasamy, K., Anand Prakash (2019). Polypharmacy and Falls: A Global Phenomenon, Age and Ageing, Volume 48, Issue Supplement_4 . [CrossRef]

- l Tehewy, M. M., Amin, G. E., & Nassar, N. W. (2015). A study of rate and predictors of fall among elderly patients in a university hospital. Journal of patient safety, 11(4), 210-214.

- Young, W. R. , & Williams, A. M. (2015). How fear of falling can increase fall-risk in older adults: applying psychological theory to practical observations. Gait & posture, 41(1), 7-12.

- Morris, R., & O’Riordan, S. (2017). Prevention of falls in hospital. Clinical Medicine, 17(4), 360.

- Miake-Lye, I. M., Hempel, S., Ganz, D. A., & Shekelle, P. G. (2013). Inpatient fall prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Annals of internal medicine, 158(5_Part_2), 390-396.

- Timmel, J., Kent, P. S., Holzmueller, C. G., Paine, L., Schulick, R. D., & Pronovost, P. J. (2010). Impact of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) on safety culture in a surgical inpatient unit. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 36(6), 252-260.

- Pitts, S. I., Maruthur, N. M., Luu, N. P., Curreri, K., Grimes, R., Nigrin, C.,... & Peairs, K. S. (2017). Implementing the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) to improve patient safety in an academic primary care practice. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(11), 591-597.

- Sedlock, E. W. , Ottosen, M., Nether, K., Sittig, D. F., Etchegaray, J. M., Tomoaia-Cotisel, A.,... & Thomas, E. J. (2018). Creating a comprehensive, unit-based approach to detecting and preventing harm in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management, 23(4), 167-175.

- Pottenger, B. C., Davis, R. O., Miller, J., Allen, L., Sawyer, M., & Pronovost, P. J. (2016). Comprehensive unit-based safety program (CUSP) to improve patient experience: how a hospital enhanced care transitions and discharge processes. Quality management in health care, 25(4), 197-202.

- Mills, A. (2012). Health policy and systems research: defining the terrain; identifying the methods. Health policy and planning, 27(1), 1-7.

- Moore, G. F. , Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W.,... & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. bmj, 350.

- https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/modules/understand/index.html.

- https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/toolkit/index.html.

- Sexton, J. B., Helmreich, R. L., Neilands, T. B., Rowan, K., Vella, K., Boyden, J.,... & Thomas, E. J. (2006). The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC health services research, 6, 1-10.

- https://patientsafety.moh.gov.my/v2/?page_id=52.

- Pandya, C., Magnuson, A., Dale, W., Lowenstein, L., Fung, C., & Mohile, S. G. (2016). Association of falls with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in older cancer survivors: A population based study. Journal of geriatric oncology, 7(3), 201-210.

- Campione, J., & Famolaro, T. (2018). Promising practices for improving hospital patient safety culture. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 44(1), 23-32.

- Christiansen, A., Coventry, L., Graham, R., Jacob, E., Twigg, D., & Whitehead, L. (2018). Intentional rounding in acute adult healthcare settings: A systematic mixed-method review. Journal of clinical nursing, 27(9-10), 1759-1792.

- Ploeg, J., Ireland, S., Cziraki, K., Northwood, M., Zecevic, A. A., Davies, B., ... & Higuchi, K. (2018). A sustainability oriented and mentored approach to implementing a fall prevention guideline in acute care over 2 years. SAGE open nursing, 4, 2377960818775433.

- Greenhalgh, T., Macfarlane, F., BARTON-SWEENEY, C. A. T. H. E. R. I. N. E., & Woodard, F. (2012). “If we build it, will it stay?” A case study of the sustainability of whole-system change in London. The Milbank quarterly, 90(3), 516-547.

- Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R. J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Cmaj, 178(12), 1555-1562.

- Mordiffi, S. Z., Ng, S. C., Ang, N. K., Lee, S. Y., Lee, M., Teng, S. T.,... & Santos, D. R. (2016). A 10-year journey in sustaining fall reduction in an academic medical center in Singapore. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 14(1), 24-33.

- Bhaduri, R. M. (2019). Leveraging culture and leadership in crisis management. European Journal of Training and Development.

- du Pisanie, J. L., & Dixon, R. (2018). Building a culture of safety in interventional radiology. Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology, 21(4), 198-204.

- Ohde, S., Terai, M., Oizumi, A., Takahashi, O., Deshpande, G. A., Takekata, M.,... & Fukui, T. (2012). The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary QI activity for accidental fall prevention: Staff compliance is critical. BMC health services research, 12(1), 1-7.

- Campione, J., & Famolaro, T. (2018). Promising practices for improving hospital patient safety culture. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 44(1), 23-32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).