1. Introduction

Focusing on green marketing, green financing, and green operations, green banking is gaining popularity in the banking industry (Lalon, 2015; Nath et al., 2014). It revolves around people, the planet, and profit, aiming to promote eco-friendly activities while ensuring financial benefits (Grant, 2008; Peattie, 2016). The main focus is on reducing paper usage and adopting electronic transactions like ATMs, mobile banking, and Internet banking (Schiederig et al., 2012; Chen, 2008; Chang, 2011). This shift conserves paper and saves fuel by allowing customers to conveniently perform transactions from anywhere. Green marketing utilises informative websites to reduce advertising costs, while green financing safeguards banks' operational capabilities, enhancing their financial stability and security (Mariadoss et al., 2011; Mostafa, 2007). Green operations involve adopting innovative practises like integrating electronic banking services, which offer savings opportunities by eliminating paper usage, reducing fuel emissions, minimising waiting times, and lowering operational costs for both banks and customers (Mourad et al., 2012).

Green marketing has been getting a lot of attention lately because more and more people care about the environment (Cherian and Jacob, 2012; Peattie, 2016). As a result, more and more businesses are incorporating environmental concerns into their goals, practises, and strategies. This is in line with environmental protection laws and regulations as well as consumer demand for environmentally friendly products (Lammgrd and Andersson, 2014; Subramanian et al., 2010; Tost et al., 2018). Companies, in particular, have used green innovation as a way to show that they care about the environment (Takalo and Tooranloo, 2021; Tolliver et al., 2021). Green innovation is often done by putting in place environmentally friendly goods and practises (Wakeford et al., 2017; Okereke et al., 2019). Green innovation also helps management by improving a company's reputation and image (Gelan, 2022), as well as business success and competitive advantage (Chiou et al., 2011; Sarma and Roy, 2021). However, not all businesses can effectively promote their green brands (Schiederig et al., 2012). Many ideas fail in the first three years they are on the market because there isn't enough dialogue (Ellahi, Jillani, and Zahid, 2021). Despite increased efforts by many companies to create environmentally friendly products, consumers are frequently ignorant of these benefits (Smith & Brower, 2012). Continued inadequate and inconsistent communication could jeopardise environmentally concerned companies' genuine investment efforts. Effective green marketing tactics must be used to elicit positive responses and involvement from customers towards companies' sustainability endeavours (Devi Juwaheer et al., 2012; Bhatia and Jain, 2013).

Also, Dangelico (2016) and Durif et al. (2010) say that the performance of environmentally friendly goods on the market is still uncertain, even though a lot of money has been put into green innovation. This is because experts and customers have different ideas about what "innovation" and "innovativeness" mean. Previous research has mostly thought of innovation as a result of a company's business activities, with a focus on technical improvements and little thought given to how customers use innovations. Because of this, these ways of thinking haven't been able to meet customers' needs (Rogers and Shoemaker, 1971). Kunz, Schmitt, and Meyer (2011) say that this gap needs to be closed by looking at innovation from the consumer's point of view. Eisingerich and Rubera (2010) say that innovativeness is a company's ability to accept new ideas and come up with new solutions, not just the results of what it does. Using this idea as a starting point, the current study describes green brand innovation as the extent to which consumers think a brand can meet their environmental needs in new and useful ways. Studies in the past have looked at how brand innovation affects brand loyalty, but none of them (Shrikanth and Raju, 2012; Henard and Dacin, 2010) have specifically looked at green brands.

Also, studies on how the innovativeness of a brand affects brand loyalty have shown mixed results (Pappu and Quester, 2016). Using the theory of signalling, this study says that the link between green brand innovation and brand loyalty is explained by the facilitation of green perceived value. The basic idea behind this is that customers won't be loyal to green brand innovations until they see value in them. Furthermore, growing consumer mistrust towards green brands (Lin, Lobo, and Leckie, 2019) shows the need for consumer education efforts related to environmental understanding. Surprisingly, earlier green innovation research has not taken the function of green knowledge into account. Consumers who are better knowledgeable about environmental issues are predicted to have less confusion in their decision-making process and to be more trusting and accepting of a brand's environmental promises (Gözükara and Çolakoğlu, 2016; Stock and Zacharias, 2013). So, a green understanding may be able to moderate the link between how innovative a brand is and how loyal its customers are to it. Overall, the goal of this study is to find out how the way customers think about green brand innovations affects their commitment to a brand. To do this, an integrative structure is set up that uses the perceived value of green as a link between the innovativeness of a green brand and customer loyalty to that brand. The study also wants to find out how green information affects this relationship.

2. Theoretical Base and Developing Hypotheses

2.1. Green Brand Innovativeness

Many companies have realised that being both "green" and "competitive" is a good plan and that green innovation is a big part of being competitive in the long term (Lin and Zhou, 2022; Stock and Zacharias, 2013). Because of this, a lot of study has been done on the development of green innovation strategies (Arham and Dwita, 2021; Choi and Han, 2019; Fankhauser et al., 2013; Mariadoss, Tansuhaj, and Mouri, 2011). Arham and Dwita (2021) highlight that green innovation encompasses both product and process innovations, with corporate environmental ethics influencing these two types of innovation. Choi and Han (2019) find that improvements in both green products and green processes positively impact a company's green brand image. Fankhauser et al. (2013) emphasise that the success of a company's green competitiveness relies on green products and green process innovations. Kalaiselvi and Dhinakaran (2021) add to the idea of innovation by saying that plans for innovation that include both technical and non-technical improvements are good for sustainable consumption behaviour. Even though green innovation has gotten a lot of attention, it has mostly been looked at at the organisational level, with innovation being described as the result of a firm's efforts. This study presents a new idea called "green brand innovativeness," which is different from "green innovation" and "green innovativeness." Gozükara and Olakolu (2016) describe it as the extent to which consumers think that a brand can meet their environmental needs in new and useful ways. In other words, how consumers see green brand innovation depends a lot on how well a company can meet the environmental needs of its customers by coming up with new and useful solutions.

2.2. Green Brand Innovativeness and Green Brand Loyalty

A recent study on green brands found that people are very loyal to green companies. Green brand loyalty is "the extent to which customers plan to buy a brand again because they have a strong attitude towards the environment and are committed to sustainability" (Lin, Lobo, and Leckie, 2017; Chen et al., 2020). Previous studies have looked at the factors that affect green loyalty, such as green trust, green satisfaction, green perceived value, and self-brand connection (Panda et al., 2020; Lin, Lobo, & Leckie, 2017). Brand innovation has the potential to impact brand loyalty in two ways. Firstly, green brand innovation can enhance consumer happiness and trust by providing effective and novel solutions aligned with environmental goals (Lin, Lobo, and Leckie, 2019). Also, green brand innovativeness shows how well a brand can keep its environmental promises, which makes people more likely to buy it again (Kang and Hur, 2012; Bashir et al.,2020; Guo et al., 2017). These studies have shown that there is a good link between brand innovation and brand loyalty. Therefore, the following hypothesis is put forth:

H1:

Green brand innovativeness positively influences green brand loyalty.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Green Perceived Value (GPV)

When two parties, the sender and the receiver, have asymmetric knowledge, signalling theory is widely used to characterise their behaviour (Chen, Y. S., and Chang, 2012; Lam, Lau, and Cheung, 2016). This theory is concerned with how the sender uses signals to transmit information and how the recipient interprets these messages. Many studies have proven how crucial the indications organisations use to communicate with their customers are because businesses and their target markets don't know as much about each other as they should (Lin and Zhou, 2022; Arora and Manchanda, 2022). Doszhanov and Ahmad (2015) describe signals as "marketer-controlled, easy-to-acquire informational signals, extrinsic to the product itself, that consumers use to form judgements about the quality or worth of the product." In a world with limited knowledge, consumers use signals to figure out how good a product is (Román-Augusto et al., 2022; Lin, Lobo, and Leckie, 2017). Studies have shown that quality factors like advertising (Doszhanov and Ahmad, 2015), brand name (Lambin, Chumpitaz, and Schuiling, 2007), price (Arora and Manchanda, 2022), and warranty (Pappu and Quester, 2016) are strongly related to a company's activities and strategies. Boksberger and Melsen (2011) said that a brand's innovativeness can predict its expected utilitarian value (Stock, 2011), competitive edge (Mukherjee and Hoyer, 2001), and ability to do the job it claims to do well (Kunz et al., 2011). The authors say that customers' views of how innovative a brand is are also related to how good they think the brand is. In the same way, knowledge is an important asset in green marketing, and companies should tell their customers about it in the right way, especially since consumers are becoming more and more aware of "greenwashing" (Román-Augusto et al., 2022; Aulia, Sukati, and Sulaiman, 2016).

Based on how innovativeness affects the quality of a brand, this study (Pappu & Quester, 2016) finds that green brand innovativeness is a good sign of green perceived value. Green perceived value refers to consumers' overall evaluation of a product or service's net benefits, taking into account their environmental desires, sustainable expectations, and green needs (Lin, Lobo, and Leckie, 2017). Consequently, consumers' green aspirations, expectations, and demands influence green perceived value, which is inherently subjective. This, in turn, increases green satisfaction, trust, self-brand connection, and brand loyalty, which, according to Lapierre (2000), leads to more plans to buy green products and better relationships between consumers and brands. So, the idea of perceived green value is very important when looking at the link between green brand innovation and customer trust. Yee and San (2011) found that a product's perceived innovativeness and how consumers see its value are closely linked. Abdou et al. (2022) and Mourad and Serag Eldin Ahmed (2012) define green brand innovativeness as a brand's ability to meet customers' environmental needs through product and process innovation. So, green brand innovation could make customers more confident in the brand's ability to live up to its green claims, which would increase the perceived value of green. Also, Abdou et al. (2022) suggested that perceived value is a key factor in repurchase intentions, good word-of-mouth, and loyalty. Sánchez et al. (2004), for example, found a link between brand loyalty and how green a product is seen to be. So, based on what we already know, we can assume that perceived green value may act as a link between green brand innovation and brand trust. So, the following hypothesis can be put forward:

H2a:

Consumers' perception of green brand innovation positively influences Green Perceived Value (GPV).

H2b:

Green Perceived Value (GPV) positively influences green brand loyalty.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Green Knowledge

Customers are more likely to buy green goods or services if they know a lot about them (Jamison, 2003; Lin and Chen, 2017). Borah et al. (2023) and Sahoo, Kumar, and Upadhyay (2023) define green knowledge as "a general knowledge of facts, concepts, and relationships about the natural environment and its major ecosystems." (Goldman, 2001) divides the writing about green knowledge into two types: abstract knowledge and concrete knowledge. People's subjective knowledge comes from how aware they think they are of important environmental issues. People's objective knowledge comes from how they use goods and how companies act in relation to environmental issues. Abstract green knowledge is better than factual green knowledge at predicting what consumers will do about environmental issues (Kurowski et al., 2022; Chitra and Gokilavani, 2020), so this study focuses on abstract green knowledge and how it affects the relationship between green brand innovativeness and perceived green value. Studies from the past (Afridi et al., 2023; Sharma and Choubey, 2022) show that educating consumers about environmental problems can make them think an environmentally friendly product is of higher quality. By making people more aware of green brands, green information can make people feel better about green products (Lindenberg and Volz, 2016). So, as people become more aware of environmental issues, they will learn more about the green value that brands provide. As a result, this study suggests that customers' knowledge of green issues makes them more likely to rate the green brand's green value higher. So, the following hypothesis has been put forward:

H3:

There is a positive relationship between green knowledge and green perceived value.

Furthermore, given the information asymmetry between customers and green brands, increased consumer green awareness reduces perceived uncertainty when making green purchasing decisions (Lalon, 2015). Customers' opinions of a company's capacity to provide relevant and novel solutions to their green demands are referred to as green brand innovativeness (Rai et al., 2019). So, the more customers know about environmental issues, the less uncertain they are and the more confident they are that the green brand can meet their green needs (Herath, 2019). As a result, they place a higher value on green. Consumers with inadequate awareness about environmental issues, on the other hand, are more likely to suffer from heightened uncertainty, which might lead to mistrust about the brand's green features. Therefore, they are less likely to accept the brand's claims about being good for the environment. Lastly, as consumers learn more about being green, they feel more unsure about green brands, which makes the effect of green brand innovation on perceived value bigger. Based on what we've talked about so far; we propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

The positive relationship between green brand innovativeness and green perceived value is Moderated by green knowledge.

2.5. Theoretical Framework

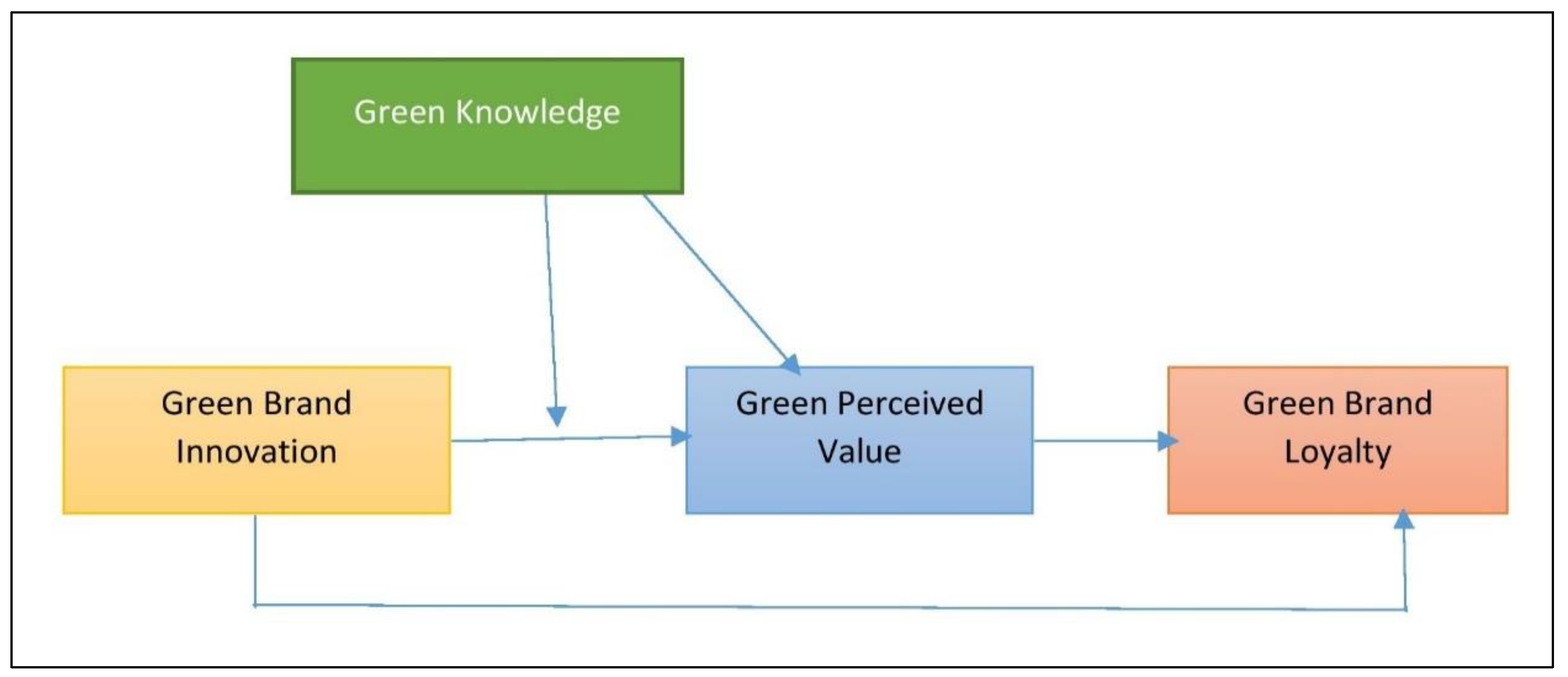

Figure 1 shows that the key concepts in the conceptual framework are green brand innovativeness, green perceived value, brand loyalty, and green knowledge. The arrows show how these ideas are thought to relate to each other. First, it is thought that the innovativeness of green brands has a positive effect on how green they are seen to be. This shows that customers think a brand is more valuable in terms of its environmental benefits when they think it is innovative when it comes to green solutions. Second, it is thought that green perceived value will be the link between green brand innovation and brand trust. It is thought that consumers will be more loyal to a brand when they think it has better environmental value. The green perceived value acts as a middleman by capturing the positive effect of green brand innovation on brand loyalty through the value that customers put on the brand. Also, green information is thought to moderate the link between how innovative a green brand is and how green it is seen to be. It is thought that when customers know more about green issues, the effect of green brand innovation on green perceived value is stronger. This means that people who know more about being green are more likely to notice and like the innovative green solutions that the brand offers. This gives the brand a higher perceived value. Overall, this conceptual framework shows how the relationships between the constructs are thought to work, with perceived value serving as a bridge between green brand innovativeness and brand loyalty. The framework also takes into account how green information affects the relationship between how innovative a green brand is and how green people think it is. It is the basis for more empirical research in the study on how green brand innovation, green perceived value, and green understanding affect brand loyalty.

3. Study Methodology

The research design upon which the study is based combines descriptive and explanatory components. To investigate the link between the independent and dependent variables, descriptive research was used. In line with findings from other studies (Afridi et al., 2023; Sharma and Choubey, 2022), the researcher used the explanatory approach to ascertain the correlation between green innovativeness, green perceived value, green knowledge, and green brand loyalty. Customers who used ATM and internet banking services offered by commercial banks in Ethiopia participated in this study. The top nine commercial banks in Ethiopia's client base served as the study's analysis unit. A sizable chunk of the total customer base is made up of the nine commercial banks, which account for about 60% of all consumers. The Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, Dashen Bank, Buna International Bank, United Bank, the Bank of Abyssinia, Nib International Bank, Wogagen Bank, Oromia Bank, and Awash International Bank are the nine commercial banks taken into account in this study.

This study used a survey strategy to gather data as part of its quantitative methodology. Using standardised questionnaires, we were able to collect primary data in the form of responses. The questionnaires were divided into two sections: Section A, which asked about respondents' names, ages, occupations, and highest levels of education; and Section B, which asked about respondents' levels of green innovation, green perceptions of value, green knowledge, and green brand loyalty. Scales that have already been verified were used to evaluate all constructs. A 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) was used to score respondents' perceptions of each topic, and

Table 1 offers a summary of all the items utilised in this study. The scale assessing green brand loyalty included four indicators produced based on Wakeford et al. (2017), whereas the scale measuring green brand innovativeness used three items modified from Schiederig, Tietze, and Herstatt (2012). Green knowledge was tested using a four-item scale produced by Gelan (2022), and the four-item scale created by Okereke et al. (2019) was used to assess GPV. Convenience sampling was used in this study to gather cross-sectional data from a sample, as it was in other survey-based studies (Abdou et al., 2022; Mourad & Serag Eldin Ahmed, 2012). The sample was stratified, guaranteeing that the banking sector would be represented by a predefined number of respondents from each strata.

Respondents from the nine main banks in Ethiopia were given 600 structured questionnaires to complete as part of this study. Out of the 600 questionnaires, 490 were returned, resulting in an 82 percent response rate. These 490 responses were considered usable for the study. Among the respondents, 51.2 percent identified as male and 48.8 percent identified as female. In terms of age distribution, 45.5 percent were between the ages of 19 and 36, 24.7 percent were aged 36–54, 22 percent were under 18, and 7.8 percent were over 54. The study found that 58.4 percent of respondents had a long-term association of over 15 years with their respective banks, 25.3 percent had a medium-term association of 6–15 years, and 16.3 percent had a short-term association of fewer than 5 years. The survey results indicated that 51.8 percent of participants had a savings account, 38 percent had a demand account, and 10.2 percent had a current account. In terms of education, 51.4 percent of respondents possessed a degree, 20.6 percent held a master's degree or higher, and 28 percent had a diploma. These demographic profiles provide important insights into the characteristics of the sample population and can assist in interpreting the study's findings. The collected data were analysed using SPSS version 24 for descriptive analysis, including response rates and respondent profiles. Additionally, the structural model was analysed using AMOS for structural equation modelling (SEM) based on Hair (2014).

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and validity tests

Using average variance extracted metrics (AVE) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the researcher evaluated the convergent validity of the latent components. All of the AVE values for latent constructs are higher than 0.50, as can be seen in

Table 1. According to Neubaum et al. (2017), this shows that the latent variables are able to account for, on average, more than half of the variance present in the indicators resulting from latent constructs. Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability were both used to determine the structures' level of reliability. The total score for composite reliability is above the acceptable threshold of 0.70. According to the criteria stated by Hair et al. (2014), the Cronbach's alpha value must be at least 0.70 for the research to be considered quantitative. Thus, convergent validity, construct reliability, internal reliability, and composite reliability have all been demonstrated to be satisfied.

4.2. Measures of Discriminant Validity

The use of discriminant validity ensures that each item used to measure a construct is distinct (Hair et al., 2014). The low association between the relevant measure and the measurements of other constructs serves as evidence (Negassa and Japee, 2023). The reliability of the discriminant was examined using the AVE. The squared correlation for each construct should be lower than the square root of the AVE of the indicators assessing the construct, according to Hair et al. (2014). According to

Table 2, there are no stronger connections across the constructs since the indicators are actually unique in how they measure each component. In summary, the suggested measuring paradigm offers good convergent and discriminant validity. Therefore, it can be said that the structural linkages and measurement qualities show good validity and reliability.

Before beginning with the study, the researcher performed many checks on the variables, including checking for normality, outliers, and missing values, to ensure that the assumptions of multivariate analysis were not broken. The researcher then examined the consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the four key components: green brand innovativeness, green brand loyalty, green perceived value, and green knowledge (see

Table 1 and

Table 2). This study employed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to carry out these tests. To check for the presence of common method variance (CMV), we utilised Harman's one-factor test, as recommended by Okereke et al. (2019). All 15 measurement items were considered together as a single general factor in the CFA. The results, however, showed that the one-factor model did not fit the data well, as evidenced by the fit indices RMSEA =.13, CFI =.81, and TLI =.76. This implies that there was no substantial problem with CMV. The four-factor structure model, on the other hand, suited the data well (X

2 (82) = 154.074, X

2/df = 1.8; CFI =.96, TLI =.94, RMSEA =.034). By contrasting the acquired results with the necessary requirements, as shown in

Table 1, the study also evaluated the validity and reliability of the measures. All standardised factor loadings were statistically significant and significantly higher than the cutoff value of 0.50 set by Hair et al. (2014). For all structures, Cronbach's alphas ranged from.79 to.85, demonstrating excellent internal consistency. Additionally, the composite reliabilities of the constructs ranged from.86 to.87, exceeding the suggested level of.70 (Hair et al., 2014). In conclusion, discriminant validity was attained, as Hair et al. (2014) suggested, because all squared correlation coefficients were lower than the average variance extracted (AVE) values.

4.3. Findings of the Structural Model

Structural equation modelling was used in this study to evaluate the conceptual framework and hypotheses shown in

Figure 1. The researcher used path analysis in accordance with Lin and Zhou's (2022) technique to evaluate moderation. With the use of Gelan's (2022) method, the items for each construct were combined into a single indicator, and the interaction term was calculated as the sum of the mean-centred variables for green brand innovativeness and green knowledge. The loadings and error variances derived from the measurement model were then used to adjust the measurement error for each construct.

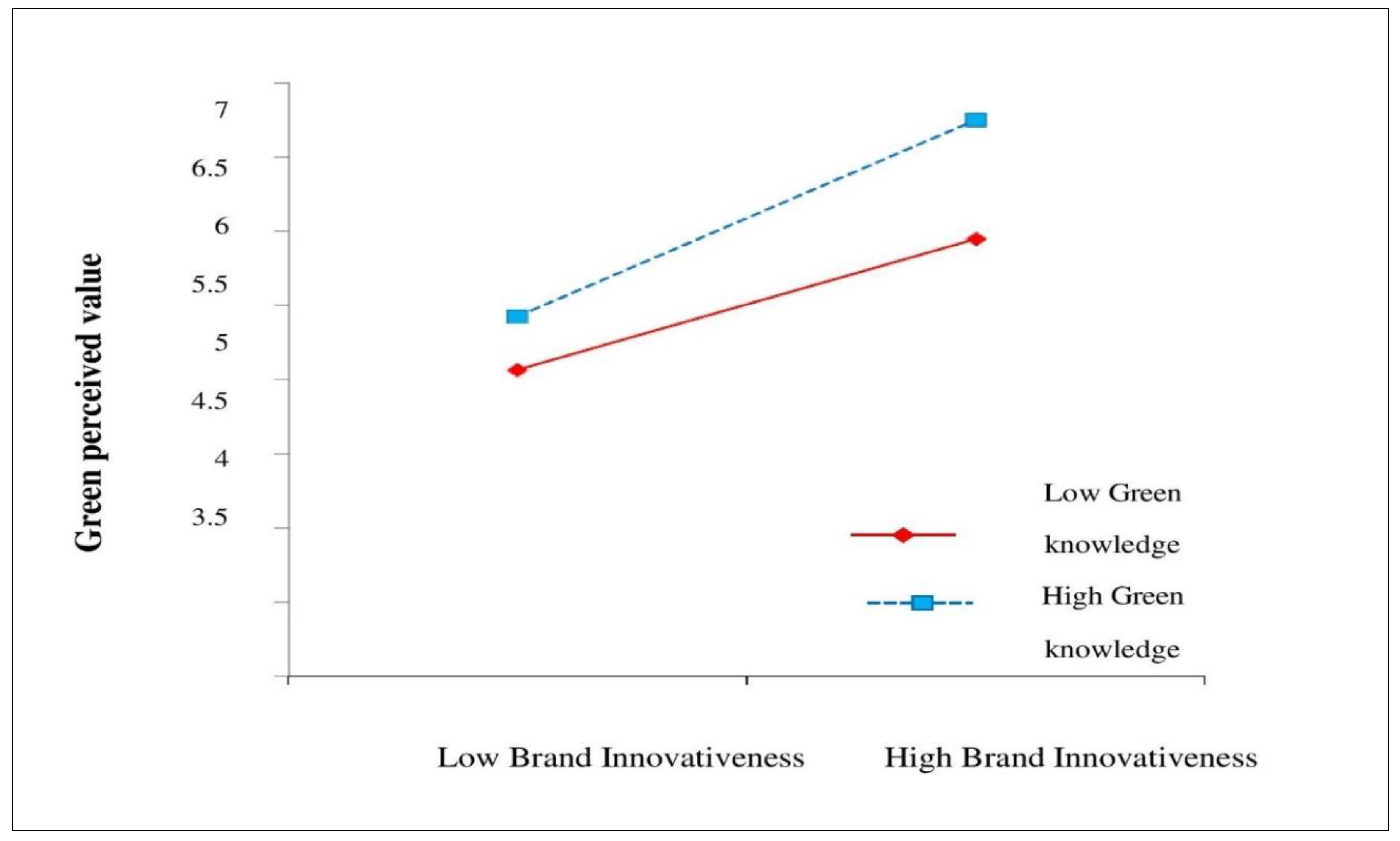

Table 3 provides a full summary of the path analysis's findings. The data support hypothesis H1 by showing that green brand innovativeness positively impacted green brand loyalty (β=.37, p<.01). Additionally, green brand innovativeness had a positive impact on green perceived value (β=.58, p<.01), which in turn showed a positive relationship with green brand loyalty (β=.61, p<.01). Thus, the mediating role of perceived green value was confirmed, supporting hypotheses H2a and H2b. Additionally, a correlation between perceived value and green knowledge was shown to be positive (β =.32, p<.01), supporting hypothesis H3. The connection between green brand innovativeness and perceived green value was found to be significantly influenced by green knowledge (β=.16, p<.01), supporting hypothesis H4. These varied consequences are graphically depicted in

Figure 2. When consumers have a high degree of green knowledge compared to when they have a low level of green knowledge, the influence of green brand innovativeness on green perceived value differs according to the significance of the interaction terms (at p<. 05).

4.4. Discussion and Implications

The purpose of this study was to find out if and how a company's level of innovation affects its customers' loyalty to green brands. For that purpose, this research investigates the connection between green brand innovativeness and brand loyalty. Furthermore, the moderating effects of consumer green knowledge and the mediating effects of perceived green value on the formation of green brand loyalty were investigated. The study's empirical findings showed that the innovativeness of green brands had an effect on consumers' perceptions of those brands, which in turn affected their loyalty to those brands (Schiederig et al., 2012; Chen, 2008; Chang, 2011). That is to say, consumers are more likely to remain dedicated to a green brand if they believe that brand to be both innovative and valuable. The results also showed that perceived value played a significant mediating role between green brand innovativeness and brand loyalty. In particular, the correlation between environmental consciousness and brand loyalty appears to be quite robust (Mariadoss et al., 2011; Mostafa, 2007). So, being innovative alone is not enough to establish a high level of customer brand loyalty in the absence of perceived green value. In order to maintain customer loyalty, green brand innovation must provide tangible benefits to buyers. Last but not least, the impact of environmental literacy on the correlation between green brand originality and value perception was uncovered (Grant, 2008; Peattie, 2016). As a result, educating consumers on environmental issues is an efficient strategy for fostering the growth of green brand loyalty by reinforcing the connection between brand originality and perceived green value.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the notion of green brand innovativeness from the perspective of actual Ethiopian consumers. The majority of the current study on green innovation has relied on managers' or experts' perspectives. This study adds to the body of knowledge on green innovation by evaluating how innovation impacts consumers. This research provides some support for the idea that big investments in green product innovation can increase the likelihood of a product's commercial success in the market (Takalo and Tooranloo, 2022). By adopting the 'innovativeness-loyalty' paradigm for use in the context of green brands, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on green innovation and green branding. Innovation in green brands has mostly gone unnoticed (Chiou, Chan, Lettice, & Chung, 2011), even though several green brand-related constructs have been discussed in recent literature (Tolliver et al., 202; Wakeford et al., 2017; Okereke et al., 2019; Gelan, 2022). This study's results provide more evidence that the innovativeness-loyalty model may be successfully applied to the case of eco-friendly firms. Green brand equity has been demonstrated to depend greatly on green brand loyalty (Sarma and Roy, 2021). As a result, if consumers think green brands are innovative, they may be more loyal to those brands, which would increase the value of green brands.

Additionally, the innovativeness-loyalty model is modified to incorporate perceived green value as a mediator using the signalling theory put forth by Yasar, Martin, and Kiessling (2020). This finding suggests that perceived green value acts as a mediator between the innovativeness of brands and their consumers' loyalty to such brands. Contrary to what Hajar et al. (2022) found, these results indicate that a brand's innovativeness has a negative impact on customer loyalty. This research's results point to a new path that customers might take to become devoted to a certain brand. Customers will be more satisfied, acquire green trust, and remain loyal to a green brand if that business is able to effectively provide fresh and valuable solutions to suit those customers' green needs. Instead of relying just on quality, we believe that customers can also take into account other key characteristics, such as perceived green benefits and transparency (Lin et al., 2017). Thus, the finding of these results lends credence to the idea that perceived green value plays a pivotal mediating function in the green brand innovation-loyalty model. Finally, the results of this study show that environmental knowledge helps weaken the relationship between perceived green value and the innovativeness of green brands. The brand tries to increase its perceived green worth by catering to consumers' environmental concerns, in accordance with the signalling theory. The progress has been aided by consumers' growing awareness of environmental issues. Consumers trust in the brands they've selected increases when they have a deeper understanding of the environmental benefits of those brands (Ellahi, Jillani, & Zahid, 2021). The results of this study corroborate the significance of consumers' knowledge of green brands as a potential modifier of this relationship. In sum, these results add to the literature on what inspires and how green brand loyalty grows (Smith & Brower, 2012).

The study's empirical findings have several managerial ramifications. An increase in green brand innovativeness has been shown to increase green brand loyalty (Devi Juwaheer et al., 2012; Smith and Brower, 2012), and this study confirms that finding. Rather than concentrating on green innovation conceived primarily from the perspective of management, businesses that want to increase green brand loyalty should work to improve consumers' impressions of a brand's innovativeness. More money should be put into R&D to create green products and services that meet consumers' apparent and hidden demands in this area. Organisations can also use online forums to spread the word about their cutting-edge thinking. Customers can have a larger hand in the co-innovation process if they are given a voice through these online communities (Devi Juwaheer et al., 2012; Smith and Brower, 2012). These green promotions can increase consumer-based brand equity by bridging the gap between green consumers' environmental beliefs and their actual purchasing behaviour (Devi Juwaheer et al., 2012; Smith and Brower, 2012). Second, consumer perceptions of the brand's green value appear to act as a mediating factor in the relationship between green brand innovativeness and loyalty. Brand loyalty is unlikely to increase if green brand innovation fails to meet consumer expectations for value. What's more, these results show that green perceived value has a rather substantial influence on green brand loyalty, which means that businesses should employ efficient communication techniques to strengthen the 'green innovativeness-green perceived value' linkages. Even though Omar et al. (2021) stated that green benefits and green transparency drive green perceived value, organisations can raise consumers' perceptions of the brand's green innovativeness to boost green perceived value. This study concludes by showing that the relationship between "green innovativeness and green perceived value" is positively moderated by consumers' green knowledge. Therefore, firms must use smart PR strategies to involve customers in green education. Companies can influence consumers' environmental awareness by, for instance, planning and taking part in environmental events, offering third-party eco-labelling and green certification, and hosting green activities.

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the fact that the current study makes some significant theoretical advancements and has some significant management implications, there are several constraints to take into account. To begin, the hypotheses in this study are tested using cross-sectional data. Therefore, gathering longitudinal data is useful for further investigating these dynamic interactions. Second, the model was only evaluated using data from Ethiopia; therefore, the study's results can only be extrapolated so far. Studying the impact of cultural differences on the formation of consumers' innovativeness towards green brands and their perceptions of green value, as well as their loyalty to green brands, can inform future research. Finally, this study may have been less fruitful had we looked at how the models for brands of tangible goods and services differed or were comparable. Thus, the postulated links might be investigated in the context of various brand types in further studies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdou, A.H.; Shehata, H.S.; Mahmoud, H.M.E.; Albakhit, A.I.; Almakhayitah, M.Y. The Effect of Environmentally Sustainable Practices on Customer Citizenship Behavior in Eco-Friendly Hotels: Does the Green Perceived Value Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, F. E. A. , Afridi, S. A., Zahid, R. A., Khan, W., & Anwar, W. (2023). Embracing green banking as a means of expressing green behaviour in a developing economy: exploring the mediating role of green culture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Arham, Q. L. , & Dwita, V. (2021, November). The Influence of Green Brand Benefit and Green Brand Innovativeness on Brand Loyalty with Green Brand Image as Mediating on (P&G) Brand Products in Padang City. In Seventh Padang International Conference On Economics Education, Economics, Business and Management, Accounting and Entrepreneurship (PICEEBA 2021) (pp. 440-446). Atlantis Press. [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Manchanda, P. Green perceived value and intention to purchase sustainable apparel among Gen Z: The moderated mediation of attitudes. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulia, S. A. , Sukati, I., & Sulaiman, Z. (2016). A review: Customer perceived value and its Dimension. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Management Studies, 3(2), 150-162. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Khwaja, M.G.; Rashid, Y.; Turi, J.A.; Waheed, T. Green Brand Benefits and Brand Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Green Brand Image. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.; Jain, A. Green Marketing: A Study of Consumer Perception and Preferences in India. Electron. Green J. 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P.E.; Melsen, L. Perceived value: a critical examination of definitions, concepts and measures for the service industry. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.S.; Dogbe, C.S.K.; Pomegbe, W.W.K.; Bamfo, B.A.; Hornuvo, L.K. Green market orientation, green innovation capability, green knowledge acquisition and green brand positioning as determinants of new product success. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 26, 364–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-G.; Zhou, X.-L. On the drivers of eco-innovation: empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The Influence of Corporate Environmental Ethics on Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Role of Green Innovation. J. Bus. Ethic- 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChenY. -S. The Driver of Green Innovation and Green Image– Green Core Competence. J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2012). Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Management Decision, 50(3), 502-520. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. S. , Huang, A. F., Wang, T. Y., & Chen, Y. R. (2020). Greenwash and green purchase behaviour: the mediation of green brand image and green brand loyalty. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 31(1-2), 194-209. [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.; Jacob, J. Green Marketing: A Study of Consumers’ Attitude towards Environment Friendly Products. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.-Y.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, V.; Gokilavani, R. Green Banking Trends: Customer Knowledge and Awareness in India. Shanlax Int. J. Manag. 2020, 8, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Han, T.-I. Green Practices among Fashion Manufacturers: Relationship with Cultural Innovativeness and Perceived Benefits. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M. Green Product Innovation: Where we are and Where we are Going. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 25, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juwaheer, T.D.; Pudaruth, S.; Noyaux, M.M.E. Analysing the impact of green marketing strategies on consumer purchasing patterns in Mauritius. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 8, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doszhanov, A.; Ahmad, Z.A. Customers’ Intention to Use Green Products: the Impact of Green Brand Dimensions and Green Perceived Value. SHS Web Conf. 2015, 18, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durif, F. , Boivin, C., & Julien, C. (2010). In search of a green product definition. Innovative Marketing, 6(1).

- Ellahi, A.; Jillani, H.; Zahid, H. Customer awareness on Green banking practices. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2021, 13, 1377–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenreck, C.; Wagner, R. The impact of perceived innovativeness on maintaining a buyer–seller relationship in health care markets: A cross-cultural study. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Bowen, A.; Calel, R.; Dechezleprêtre, A.; Grover, D.; Rydge, J.; Sato, M. Who will win the green race? In search of environmental competitiveness and innovation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelan, E. Green Building Concepts and Technologies in Ethiopia: The Case of Wegagen Bank Headquarters Building. Technologies 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M. (2001). The birth of a discipline: Producing authoritative green knowledge, World Bank-style. Ethnography, 2(2), 191-217. [CrossRef]

- Gözükara, İ. , & Çolakoğlu, N. (2016). Research on generation Y students: Brand innovation, brand trust and brand loyalty. International Journal of Business Management and Economic Research, 7(2), 603-611.

- Grant, J. (2008). Green marketing. Strategic direction, 24(6), 25-27. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Tao, L.; Li, C.B.; Wang, T. A Path Analysis of Greenwashing in a Trust Crisis Among Chinese Energy Companies: The Role of Brand Legitimacy and Brand Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethic- 2015, 140, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, M.A.; Alkahtani, A.A.; Ibrahim, D.N.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Alkawsi, G.; Iahad, N.A.; Darun, M.R.; Tiong, S.K. The Effect of Value Innovation in the Superior Performance and Sustainable Growth of Telecommunications Sector: Mediation Effect of Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H. M. A. K. , & Herath, H. M. S. P. (2019). Impact of Green banking initiatives on customer satisfaction: A conceptual model of customer satisfaction on green banking. Journal of Business and Management, 1(21), 24-35.

- Jamison, A. The making of green knowledge: the contribution from activism. Futures 2003, 35, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvi, S. , & Dhinakaran, D. P. (2021). Green Marketing: A Study of Consumers Attitude towards Eco-Friendly Products in Thiruvallur District. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 6026-6036.

- Kang, S.; Hur, W.-M. Investigating the Antecedents of Green Brand Equity: A Sustainable Development Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W. , Schmitt, B., & Meyer, A. (2011). How does perceived firm innovativeness affect the consumer? Journal of Business Research, 64, 816–822. [CrossRef]

- Kurowski. ; Rutecka-Góra, J.; Smaga, P. Is knowledge on climate change a driver of consumer purchase decisions in Poland? The case of grocery goods and green banking. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalon, R. M. (2015). Green banking: Going green. International Journal of Economics, finance and management sciences, 3(1), 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.Y.C.; Lau, M.M.; Cheung, R. Modelling the Relationship among Green Perceived Value, Green Trust, Satisfaction, and Repurchase Intention of Green Products. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2016, 12, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, J. J. , Chumpitaz, R., & Schuiling, I. (2007). Market-driven management: Strategic and operational marketing. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lammgård, C.; Andersson, D. Environmental considerations and trade-offs in purchasing of transportation services. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 10, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, J. Customer-perceived value in industrial contexts. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2000, 15, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhou, Z. The positioning of green brands in enhancing their image: the mediating roles of green brand innovativeness and green perceived value. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 17, 1404–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. Green brand benefits and their influence on brand loyalty. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. , Lobo, A., & Leckie, C. (2017). The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. The influence of green brand innovativeness and value perception on brand loyalty: the moderating role of green knowledge. J. Strat. Mark. 2017, 27, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-S. Determinants of green competitive advantage: the roles of green knowledge sharing, green dynamic capabilities, and green service innovation. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, N. , & Volz, U. (2016). Green banking regulation: setting out a framework. Report for the Practitioners ‘Dialogue on Climate Investments (PDCI). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- Mariadoss, B.J.; Tansuhaj, P.S.; Mouri, N. Marketing capabilities and innovation-based strategies for environmental sustainability: An exploratory investigation of B2B firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. A hierarchical analysis of the green consciousness of the Egyptian consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M.; Ahmed, Y.S.E. Perception of green brand in an emerging innovative market. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Hoyer, W.D. The Effect of Novel Attributes on Product Evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, V. , Nayak, N., & Goel, A. (2014). Green banking practices–A review. IMPACT: International journal of research in business management (IMPACT: IJRBM) Vol, 2, 45-62.

- Neubaum, D. O. , Thomas, C. H., Dibrell, C., & Craig, J. B. (2017). Stewardship climate scale: An assessment of reliability and validity. Family Business Review, 30(1), 37-60. [CrossRef]

- Okereke, C.; Coke, A.; Geebreyesus, M.; Ginbo, T.; Wakeford, J.J.; Mulugetta, Y. Governing green industrialisation in Africa: Assessing key parameters for a sustainable socio-technical transition in the context of Ethiopia. World Dev. 2019, 115, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.A.; Kassim, A.S.; Alam, S.S.; Zainol, Z. Perceived retailer innovativeness and brand equity: mediation of consumer engagement. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 41, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, T. K. , Kumar, A., Jakhar, S., Luthra, S., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Kazancoglu, I., & Nayak, S. S. (2020). Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. Journal of Cleaner Production, 243, 118575. [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R. , & Quester, P. G. (2016). How does brand innovativeness affect brand loyalty? European Journal of Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. (2016). Green marketing. In The marketing book (pp. 595-619). Routledge.

- Rai, R., Kharel, S., Devkota, N., & Paudel, U. R. (2019). Customers’ perception on green banking practices: A desk. The Journal of Economic Concerns, 10(1), 82-95.

- Román-Augusto, J. A. , Garrido-Lecca-Vera, C., Lodeiros-Zubiria, M. L., & Mauricio-Andia, M. (2022). Green Marketing: Drivers in the Process of Buying Green Products—The Role of Green Satisfaction, Green Trust, Green WOM and Green Perceived Value. Sustainability, 14(17), 10580. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How do green knowledge management and green technology innovation impact corporate environmental performance? Understanding the role of green knowledge acquisition. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P.; Roy, A. A Scientometric analysis of literature on Green Banking (1995-March 2019). J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2020, 11, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiederig, T.; Tietze, F.; Herstatt, C. Green innovation in technology and innovation management - an exploratory literature review. R&D Manag. 2012, 42, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Choubey, A. Green banking initiatives: a qualitative study on Indian banking sector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikanth, R. , & Raju, D. S. N. (2012). Contemporary green marketing-Brief reference to Indian scenario. International Journal of Social Sciences & Interdisciplinary Research, 1(1), 26-39.

- Smith, K.T.; Brower, T.R. Longitudinal study of green marketing strategies that influence Millennials. J. Strat. Mark. 2012, 20, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R.M. How does product program innovativeness affect customer satisfaction? A comparison of goods and services. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 39, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R. M. , & Zacharias, N. A. (2013). Two sides of the same coin: How do different dimensions of product program innovativeness affect customer loyalty? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(3), 516-532. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R.; Talbot, B.; Gupta, S. An Approach to Integrating Environmental Considerations Within Managerial Decision-Making. J. Ind. Ecol. 2010, 14, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takalo, S.K.; Tooranloo, H.S.; Parizi, Z.S. Green innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolliver, C.; Fujii, H.; Keeley, A.R.; Managi, S. Green Innovation and Finance in Asia. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2020, 16, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tost, M.; Hitch, M.; Chandurkar, V.; Moser, P.; Feiel, S. The state of environmental sustainability considerations in mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeford, J. J. , Gebreeyesus, M., Ginbo, T., Yimer, K., Manzambi, O., Okereke, C.,... & Mulugetta, Y. (2017). Innovation for green industrialisation: An empirical assessment of innovation in Ethiopia's cement, leather and textile sectors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 166, 503-511. [CrossRef]

- Yasar, B.; Martin, T.; Kiessling, T. An empirical test of signalling theory. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 43, 1309–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, C.J.; San, N.C. Consumers' perceived quality, perceived value and perceived risk towards purchase decision on automobile. American journal of economics and business administration 2011, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).