1. Introduction

Disordered eating patterns are a mental illness burden affecting millions globally and bringing personal, family, and societal costs [

1]. Family functioning has already been recognized as a relevant factor in eating disorders [

2]. The guidelines for eating disorders from the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) [

3] suggest eating disorders should be managed on an outpatient basis, and put the family at the center of interventions targeted to deal with them. Even successful interventions for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa are family-based [

4]. It has been reported that individuals with disordered eating behaviors are more likely to have negative core beliefs than those without this pathology [

5,

6]. Research from Saudi Arabia has identified eating disorders in young Saudi people [

7,

8]; however, no study has investigated family functioning and negative thoughts as predictors of this disorder in this population. In addition, research investigating the moderation of gender in eating problems has shown inconsistent results [

9,

10]. The present study presents a moderated mediated model associating family functioning and eating disorders with the mediation of negative automatic thoughts and moderation of gender among Saudi youth.

1.1. Family Functioning and Disordered Eating Patterns

Research shows that children’s behaviors are learned through observation of their environment, starting at home [

11], and that children learn eating patterns from their families from parental responses to their actions [

12]. Research indicates that parents of children with eating disorders are more likely to be concerned about their body image and even have disordered eating patterns themselves [

13,

14]. Families that emphasize attractiveness and thinness tend to produce people who develop eating disorders sooner or later [

15]. In fact, it was found that daughters with eating disorders had controlling mothers who restricted their eating habits, pressured them to diet, and perceived them as overweight and less attractive [

16].

Family issues were reported in a set of key eating disorders [

17,

18,

19]. Among the family issues related to eating disorders, one can cite high conflict levels in families, poor parental care, unhealthy relationships with parents, controlling parents, unhealthy family environments, parents pressing children to diet, and abuse in the family [

20,

21,

22]. It was reported by [

23] in a study on mothers and their daughters with eating disorders that the mothers tended to report low family cohesion and flexibility and poor communication with their daughters. Similarly, it was reported that patients with bulimic eating disorders perceived their families as conflictual rather than cohesive [

24]. Perceptions of living in a poor family environment were also reported to contribute to disordered eating patterns [

25]. Although most previous research focused on poor family environments, a meta-analytic study reported that healthy family factors are protective factors for eating problems [

26].

Previous studies have focused on disordered family functioning as a predictor of disordered eating patterns, and few considered healthy family functioning [

27]. This study focuses on healthy family functioning as a predictor of disordered eating patterns. Accordingly, its first hypothesis is:

H1: Healthy family functioning is negatively associated with disordered eating patterns.

1.2. The Mediating Role of Negative Automatic Thoughts

Negative core beliefs are believed to play an important role in developing and maintaining mental illnesses such as affective disorders, anxiety, depression, and personality disorders [

28]. It has also been postulated that eating disorders are mainly cognitive disorders with cognitive distortions characterized by unusual beliefs about one’s body weight and shape [

29].

Automatic thoughts are defined by [

30] as unplanned thoughts that occur from moment to moment and flow through our minds constantly. [

31,

32] proposed three types of thoughts that play a role in the maintenance of eating disorders—positive automatic thoughts, negative automatic thoughts, and permissive thoughts. Examples relating to eating are—“If I eat, I won’t feel the pain anymore” as an automatic positive thought; “If I eat, I will be fat” as an automatic negative thought, and “I will just have one more bite” as a permissive thought. It has been argued that negative thoughts play a key role in the formation of eating disorders [

32,

33]. Accordingly, this study focuses on negative automatic thoughts as a predictor of disordered eating patterns.

Toxic family environments were reported among the key factors of eating disorders. [

34] claimed that childhood trauma would influence eating disorders through negative core beliefs. Similarly, this was reported in sexually abused women [

35]. Accordingly, the second hypothesis is:

H2: Negative automatic thoughts negatively mediate the relationship between family functioning and disordered eating patterns.

1.3. The Moderation of Gender

Research has demonstrated that eating disorders are more prevalent in females than males [

36]. Nonetheless, evidence of the moderation of gender has yielded results. [

10] reported that gender moderated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and eating disorders. However, a meta-analysis study conducted by [

37] concluded that the association between family factors and eating disorders was moderated by gender. [

38] also reported moderation of gender between self-criticism, perfectionism and eating disorders, although other studies reported none [

9,

39]. It is, therefore, legitimate to hypothesize that the relationship between family environment and eating disorders may be different in females and males.

Hypothesis 3: Gender moderates the relationship between family environment and eating disorder.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Participants

This study used a cross-sectional design and a convenience sampling method to reach as large a number and diversity of participants as possible. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from King Abdul Aziz University. Participants were contacted via online platforms, including email, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter. The survey’s landing page informed the respondents about the survey’s purpose and outcome, and they provided informed consent. A total of 440 respondents agreed to participate in the study and completed it. About 71.3% were 18–20 years old and 28.7 % were 20–21 and 70.9% were females. About 95.9% were college students, and 4.1% were high school students. About 24.1% were from households whose monthly income was less than 5000SR; 26.8% from households with a monthly income of 5000–10000SR; 24.5% from households whose monthly income was 10000–15000SR; 11.4% from households with a monthly income of 15000–20000SR, and 13.2% from households whose monthly income was 20000SR and more. About 1.8% of the sample rated their health as poor, 15.9% as not so good, 26.4% as good, 29.5% as very good, and 26.4% as excellent. About 19.5% of the respondents admitted to having visited a specialist. About 3.7% went to a specialist for anorexia problems, 8.6% for obesity reasons, 4.1% for being thin, 19.1% for other reasons, and 64.5% refused to say. Forty percent had done physical activity only once or never at all, 16.8% did it 1–3 times a month, 19.1% once a week, 18.2% 3–4 times a week, and 5.9% almost every day. About 7.7% rated their appearance as poor, 17.7% rated it as not so good, 20.4% as good, 40% as good, and 5.9% as excellent. Concerning their BMIs, about 15.7% were underweight, 43.2% were of a healthy weight, 25.2% overweight, and 15.9% were obese.

2.2. Measures

The survey included the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) [

40], the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ negative) [

41], and the Brief Family Relationship Scale (BFRS) [

42], as well as a range of socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, education, monthly household income, self-rated health, physical activity, body mass index, whether they visited a specialist, the reason for that visit, and a self-judgment of their appearance.

The 26-item scale for EAT-26 assesses disordered eating patterns and is scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1–6 (never–always). The scores are recorded as 1 = 0, 2 = 0, 3 = 0, 4 =1, 5 = 2, and 6 = 3, except for item 26, which must be reversely recorded [

40]. Final scores can range from 0 to 78, where higher scores indicate greater disordered eating behavior. The scale has exhibited good psychometric properties [

40], and its internal consistency reliability was adequate in this study (Cronbach’s alpha =0.87).

The 30-item questionnaire for ATQ negative [

41] is designed to measure negative automatic thoughts and frequent negative self-evaluations. It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1–5 (not at all–all the time). Its final scores can range from 30 to 150, with higher scores indicating a frequent appearance of negative automatic thoughts. The scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties [

41], and its internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96) in this study.

The 16-item scale for BFRS [

42] measures positive family functioning. It is scored from 1–3 (not at all–a lot) and has three subscales, namely cohesiveness (7 items), expressiveness (3 items), and conflict (6 items). The conflict subscale is reverse coded so that high scores indicate little conflict in the family and, consequently, positive family functioning. The total score is calculated by summing the subscale scores, and higher scores indicate positive family functioning [42, 43]. Its final scores can range from 16 to 48. The scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties, and its internal consistency reliability in this study was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

2.3. Data Analysis

The analysis was conducted in RStudio [

44]. The descriptive statistics, ANOVA tests, and Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables were calculated first. Cronbach’s alphas were calculated using the ‘psych’ package [

45] to check the internal consistency reliability of the scales. Model 4 of the PROCESS MACRO plug-in developed by [

46] was used to test the mediation analysis. Model 8 of PROCESS MACRO was preferred for the moderated mediation analysis, as suggested by [

46]. For bootstrapping, 95% confidence intervals with 10,000 bootstrap samples were used; those intervals without a 0 are significant and indicate significant conditional indirect effects. In this analysis, the independent variable and mediation variable were mean-centered.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics and the Pearson correlation of the study variables are shown in

Table 1. The mean score for disordered eating patterns was 11.2 (SD = 8.66), the average score for negative automatic thoughts was 65.15 (SD = 25.90), and the mean score for the family environment was 36.75 (SD = 6.29). Disordered eating patterns were positively correlated with negative automatic thoughts (r = 0.34, p<0.001) and negatively correlated with family environment (r = -0.27, p<0.001).

In terms of differences, females exhibited greater scores of disordered eating patterns than males, but there were no gender differences in family environment and negative automatic thoughts (

Table 2).

3.1. Testing the Mediation Model

Model 4 of the PROCESS MACRO was used with age, body mass index, and self-rated health as covariates to answer the first hypothesis. The results indicated that the family environment was negatively associated with eating disorders (β = -0.49, p<0.001) in the absence of the mediator. These results support Hypothesis 1. When the mediator was included, the family environment was negatively associated with eating disorders (β = -0.18, p<0.001), and the strength of the relationship was significantly reduced. Negative automatic thoughts were positively related to eating disorders (β = 0.09, p<0.001).

Bootstrap methods were then employed to test the mediation analysis; the results are summarized in

Table 4. The indirect relationship between family environment and eating disorder through negative automatic thoughts was -0.13 (95% CI = -0.18 to -0.08). In addition, the index of moderation was significant at 0.09 (95% CI = 0.017 to 0.180) These confidence intervals didn’t contain 0, indicating the mediation model was significant. These results support Hypothesis 2.

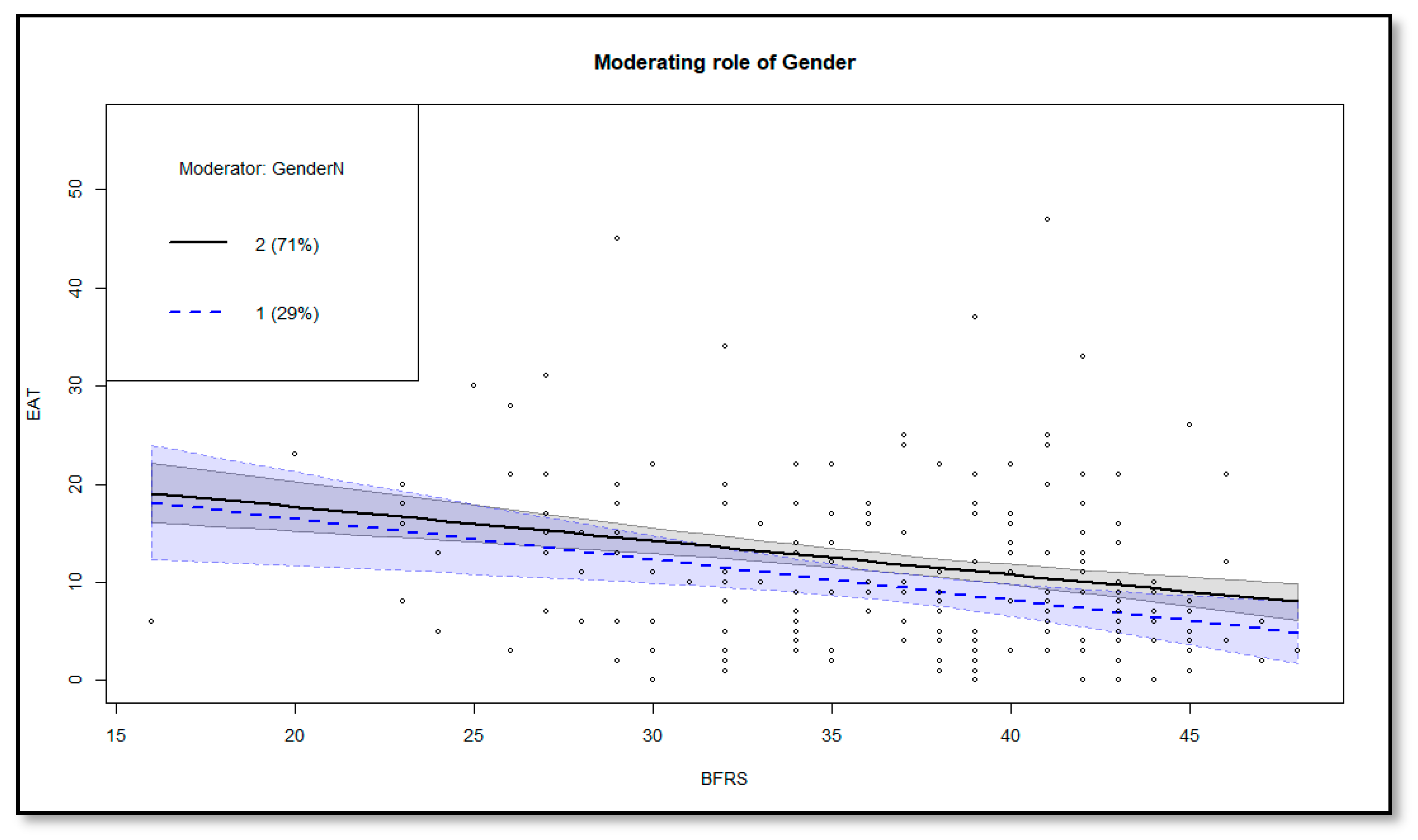

3.2. Testing the Moderated Mediation Model

Conditional direct and conditional indirect relationships between family environment and eating disorders, based on gender, were investigated to respond to Hypothesis 3 (

Table 5). The conditional direct relationship between family environment and eating disorders was significant for females -0.16 (95% CI = -0.31, -0.01) but not for males -0.14 (95% CI = -0.41, 0.13). The conditional indirect relationship between family environment and eating disorders was significant for females -0.27 (95% CI = -0.39, -0.17) and males -0.18 (95% CI = -0.25, -0.11), but it was stronger in females. These results support Hypothesis 3 and are plotted in

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

Eating disorders are a mental illness burden for many people around the world. It is, therefore, important to understand the antecedents associated with them. This study investigated the relationship between family environment and disordered eating patterns, the mediating role of automatic thoughts, and the moderation of gender. The main findings reveal that a healthy family environment is negatively related to eating disorders and that negative automatic thoughts negatively mediate this relationship. In addition, the moderation findings indicate that these relationships are more substantial in females.

The study’s results suggest that healthy family functioning is negatively associated with disordered eating patterns. This evidence corroborates previous studies [

27,

47]. A narrative review by [

48,

49] also concluded that a healthy family environment could be a protective factor against eating disorders and suggested eating disorders be treated within the family context. Some prospective studies examined parent and family functioning as predictors of disordered eating patterns and found that was the case [

50,

51]. On the other hand, disharmony in the family’s psychological climate was found to impact children’s eating disorders [

16]. People with eating disorders often reported conflict, disharmony, and little cohesion in their families [

16]. A study conducted by [

52] on the family factors contributing to the development of disordered eating patterns concluded that a dysfunctional family climate was related to eating disorders.

This study’s findings suggest that negative automatic thoughts negatively mediated the relationship between family functioning and disordered eating patterns. These results are align with those of prior research documenting negative core beliefs’ mediating role in eating disorders [

53,

54,

55]. Similarly, [

56] reported that chaotic family functioning was related to the development of eating disorders through negative belief systems. A longitudinal study of eating disorders by [

57] found that negative thoughts mediated the relationship between weight discrepancies and anorexia and bulimia. These findings align with the view that negative thoughts about food, body weight, and eating contribute developing and maintaining eating disorders [

58].

This study found that the direct relationship between family environment and eating disorders is significant only in females. The indirect relationship between family environment and eating disorders through negative automatic thoughts is more potent in females. This aligns with a similar study that found that the relationship between self-critical perfectionism and eating disorder was stronger in females [

38]. Other studies have also reported moderation of gender in eating problems [

37,

10]. These differences may be attributable to cognitions about eating, body shape, and BMI, as, by nature, females are more concerned with thinness [

9]. However, the results do not corroborate those that found no moderation of gender [

9,

39]. These inconsistencies may be due to the different designs and sampling methods employed in different studies. More research is encouraged to gain a greater understanding of the issue.

In terms of differences, the results indicated gender differences where females had higher eating disorder scores than their counterparts, but there were no gender differences in the family environment and negative automatic thoughts. Gender differences have also been reported in previous studies [

59,

36].

This study has limitations. It used a cross-sectional design, so causation cannot be inferred. Future research should use a prospective, longitudinal design for further insight. The study also used a convenience sample; future research should use random sampling methods. Moreover, the number of males was not proportionate to that of the females; future research should use a more proportionate sample.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship between family functioning and eating disorders. It found that healthy family functioning is negatively associated with eating disorders, negative automatic thoughts negatively mediate this relationship, and more intensely in females. These findings suggest that interventions targeted at preventing eating disorders can be directed at enhancing healthy family functioning and training individuals how to challenge the appearance of negative thoughts. However, they should be mindful of gender.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mogeda El Keshky; Data curation, Mogeda El Keshky; Formal analysis, Mogeda El Keshky; Funding acquisition, Badra Alganami; Investigation, Mogeda El Keshky and Badra Alganami; Methodology, Mogeda El Keshky; Writing original draft– review & editing, Mogeda El Keshky and Badra Alganami.

Funding

This study was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (G: 28-246-1443).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional review board of the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) of King Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects were informed about the study and all provided informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Schaumberg, K.; Welch, E.; Breithaupt, L.; Hübel, C.; Baker, J.H.; Munn-Chernoff, M.A. , Yilmaz, Z.; Ehrlich, S.; Mustelin, L.; Ghaderi, A.; et al. The Science Behind the Academy for Eating Disorders’ Nine Truths About Eating Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M. Measurement of eating disorder psychopathology. In Eating disorders and obesity; Fairburn, C.G., Brownell, K.D. Eds.; The Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Eating Disorders. Core Interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders; British Psychological Society; Leicester, UK, 2004; PMID: 23346610. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23052428.

- Lock, J.; Le Grange, D. Family-based treatment of eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, N.; Waller, G.; Thomas, G. Core beliefs in anorexic and bulimic women. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1999, 187, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, G.; Ohanian, V.; Meyer, C.; Osman, S. Cognitive content among bulimic women: The role of core beliefs. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 28, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Azeem Taha, A.A.; Abu-Zaid, H.A.; El-Sayed Desouky, D. Eating Disorders Among Female Students of Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Arch. Iran. Med. 2018, 21, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jawed, A.; Harrison, A.; Dimitriou, D. The Presentation of Eating Disorders in Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehak, A.; Racine, S.E. ‘Feeling fat’ is associated with specific eating disorder symptom dimensions in young men and women. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, J.; Douilliez, C. Perfectionism, rumination, and gender are related to symptoms of eating disorders: A moderated mediation model. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017, 116, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Ross, D.; Ross, S.A. Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psych. 1963, 66, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J. Psychological Treatment of Food Refusal in Young Children. Child Adol. Ment. H. 2002, 7, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annus, A.M.; Smith, G.T.; Fischer, S.; Hendricks, M.; Williams, S.F. Associations among Family-of-Origin Food-Related Experiences, Expectancies, and Disordered Eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007, 40, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K.M.; Rodin, J. Mothers, Daughters, and Disordered Eating. J. Abnorm. Psych. 1991, 100, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Shuster, B.; Blackmore, E.; Fox, J. Looking Good - Family Focus on Appearance and the Risk for Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E. Stice, E. Sociocultural Influences on Body Image and Eating Disturbance. In Eating disorders and obesity; Fairburn, C.G., Brownell, K.D. Eds.; The Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Hume-Wright, A. Lay theories of anorexia nervosa. J. Clin Psychol, 1992, 48, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth-Hoeppner, S. The critical shapes of body image: The role of culture and family in the production of eating disorders. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.C.; Pruitt, J.A.; Mann, L.M.; Thelen, M.H. Attitudes and knowledge regarding bulimia and anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignon, A.; Beardsmore, A.; Spain, S.; Kuan, A. “Why i won’t eat”: Patient testimony from 15 anorexics concerning the causes of their disorder. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patching, J.; Lawler, J. Understanding women’s experiences of developing an eating disorder and recovering: A life-history approach: Feature. Nurs. Inq. 2009, 16, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S. Untreated recovery from eating disorders. Adolescence 2004, 39, 361–371. [Google Scholar]

- Vidović, V.; Jureša, V.; Begovac, I.; Mahnik, M.; Tocilj, G. Perceived family cohesion, adaptability and communication in eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2005, 13, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Flach, A. Family characteristics of 105 patients with Bulimia. Am. J. Psychiat. 1985, 142, 1321–1324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, S.; Vieira, A.I.; Rodrigues, T.; Machado, P.P; Brandão, I.; Timóteo, S.; Nunes, P.; Machado, B. Adult attachment in eating disorders mediates the association between perceived invalidating childhood environments and eating psychopathology. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5478–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon-Daly, J.; Serpell, L. Protective factors against disordered eating in family systems: A systematic review of research. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holston, J.I.; Cashwell, C.S. Assesment of family functioning and eating disorders - The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Coll. Couns. 2000, 3, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Leung, N.; Harris, G. Dysfunctional core beliefs in eating disorders: A review. J. Cogn. Psychot. 2007, 21, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Welch, S.L.; Doll, H.A.; Davies, B. A.; O’Connor, M.E. Risk Factors for Bulimia Nervosa A Community-Based Case-Control Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997, 54, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padesky, C.A.; Greenberger, D. Clinician’s guide to mind over mood. Guilford Publishing; New York, NY, USA, 1995.

- Cooper, M.J.; Todd, G., & Wells, A. Bulimia nervosa: A client’s guide to cognitive therapy, Jessica Kingsley, London, UK, 2000.

- Cooper, M.J.; Wells, A.; Todd, G. A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. Brit J. Clinl Psychol. 2004, 43, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.; Todd, G.; Woolrich, R.; Somerville, K.; Wells, A. Assessing eating disorder thoughts and behaviors: The development and preliminary evaluation of two questionnaires. Cognitive Ther. Res. 2006, 30, 551–570. [CrossRef]

- Ford, G.; Waller, G.; Mountford, V. Invalidating childhood environments and core beliefs in women with eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartt, J.; Waller, G. Child abuse, dissociation, and core beliefs in bulimic disorders. Child Abuse Neglect 2002, 26, 923–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; Rosselli, F.; Perrin, N.; DeBar, L.; Wilson, G.T.; May, A.; Kraemer, H.C. Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2009, 42, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles Marcos, Y.; Quiles Sebastián, M.J.; Pamies Aubalat, L.; Botella Ausina, J.; Treasure, J. Peer and family influence in eating disorders: A meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiat. 2013, 28, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Davies, B. Clinical perfectionism and eating psychopathology in athletes: The role of gender. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2015, 74, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingleton, R.M.; Thompson-Brenner, H.; Pratt, E.M.; Thompson, D.R.; Franko, D.L. Gender differences in clinical trials of binge eating disorder: An analysis of aggregated data. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 2015, 83, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical Correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, S.D.; Kendall, P.C. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Ther. Res. 1980, 4, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, C.C.T.; Allen, J.; Henry, D.; Team, P.A. The Brief Family Relationship Scale: A Brief Measure of the Relationship Dimension in Family Functioning. Assessment 2014, 21, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saputra, F.; Yunibhand, J.; Sukratul, S. Relationship between personal, maternal, and familial factors with mental health problems in school-aged children in Aceh province, Indonesia. Asian J. Psychiat. 2017, 25, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rstudio Team, Rs. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA, 2022. Available online: www.rstudio.com/.

- Revelle, W. Using the psych package to generate and test structural models 2017. Available online: https://personality-project.org/r/psych_for_sem.pdf.

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA, 2013. A: to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis.

- Kroplewski, Z.; Szcześniak, M.; Furmańska, J.; Gójska, A. Assessment of family functioning and eating disorders - the mediating role of self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erriu, M.; Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L. The role of family relationships in eating disorders in adolescents: A narrative review. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 3390. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.P.; Sadeh-Sharvit, S. Preventing eating disorders and disordered eating in genetically vulnerable, high-risk families. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.G.; Cohen, P.; Kasen, S.; Brook, J.S. Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. Am. J. Psychiat. 2002, 159, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoebridge, P.; Gowers, S.G. Parental high concern and adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: A case-control study to investigate direction of causality. Brit. J. Psychiat. 2000, 176, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluck, A.S. (2008). Family factors in the development of disordered eating: Integrating dynamic and behavioral explanations. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.J.; Leung, N.; Harris, G. (2006). Father-daughter relationship and eating psychopathology: The mediating role of core beliefs. Brit. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 45, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, H.M.; Rose, K.S.; Cooper, M.J. (2005). Parental bonding and eating disorder symptoms in adolescents: The meditating role of core beliefs. Eat. Behav. 2005, 6, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G.; Meyer, C.; Ohanian, V.; Elliott, P.; Dickson, C.; Sellings, J. The psychopathology of bulimic women who report childhood sexual abuse: The mediating role of core beliefs. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G.; Kennerley, H.; Ohanian, V. Schema-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders. In Cognitive schemas and core beliefs in psychological problems: A scientist-practitioner guide, Riso, L.P., Du Toit, P.L., Stein, D.J., Young, J.E. Eds; American Psychological Association, 2007; pp. 139–175. 1037. [CrossRef]

- Zarychta, K.; Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U. The association between automatic thoughts about eating, the actual-ideal weight discrepancies, and eating disorders symptoms: A longitudinal study in late adolescence. Eat. Weight Disord. 2014, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.; Fairburn, C.G. Thoughts about eating, weight and shape in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Behav. Res. Ther. 1992, 30, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P.M.; Seeley, J.R.; Moerk, K.C.; Striegel-Moore, R.H. Gender differences in eating disorder symptoms in young adults. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 32, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).