Submitted:

03 July 2023

Posted:

06 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Housing

1.2. Residential Satisfaction

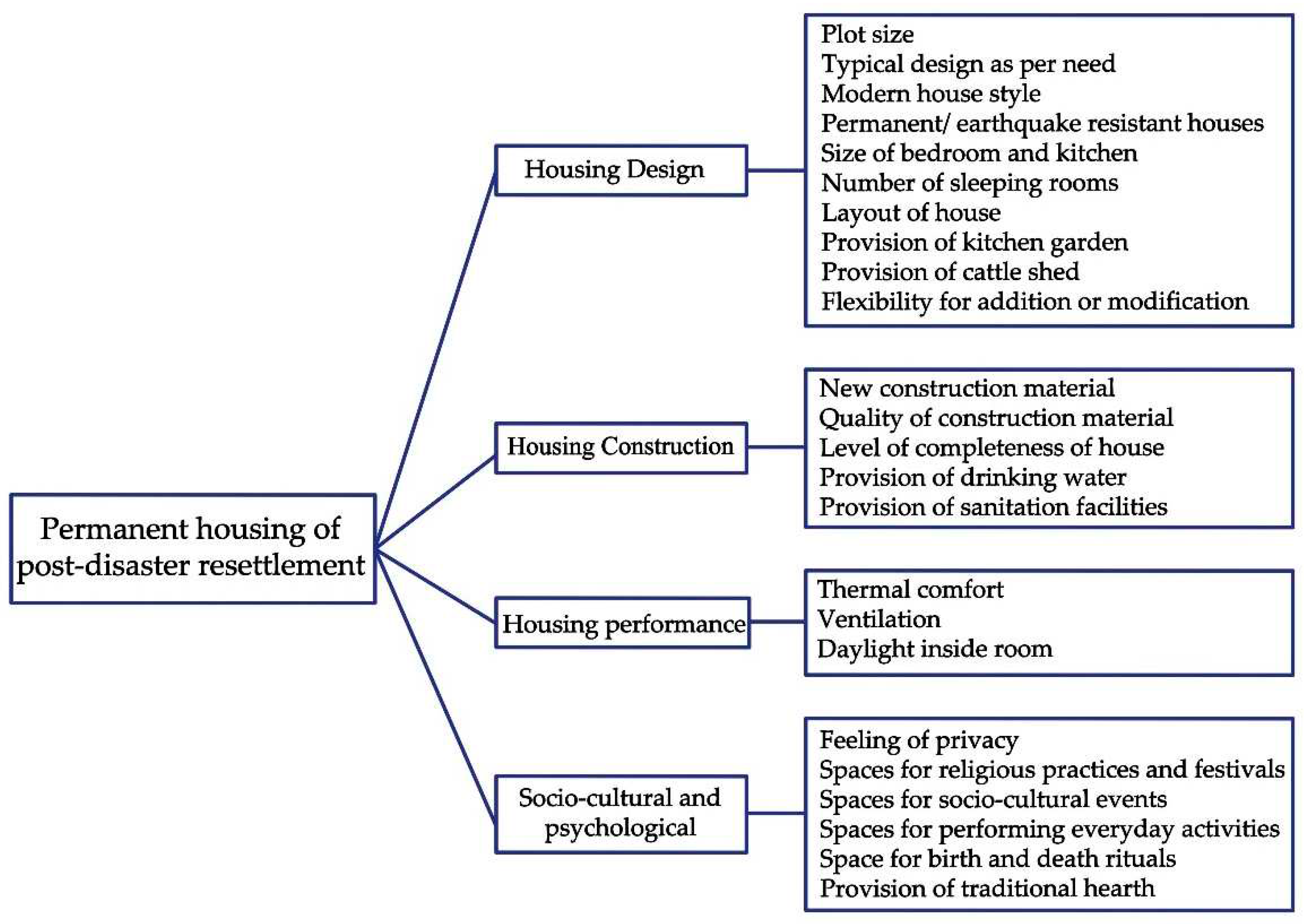

1.3. Factors Influencing Residential Satisfaction in Post-Disaster Resettlement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Area

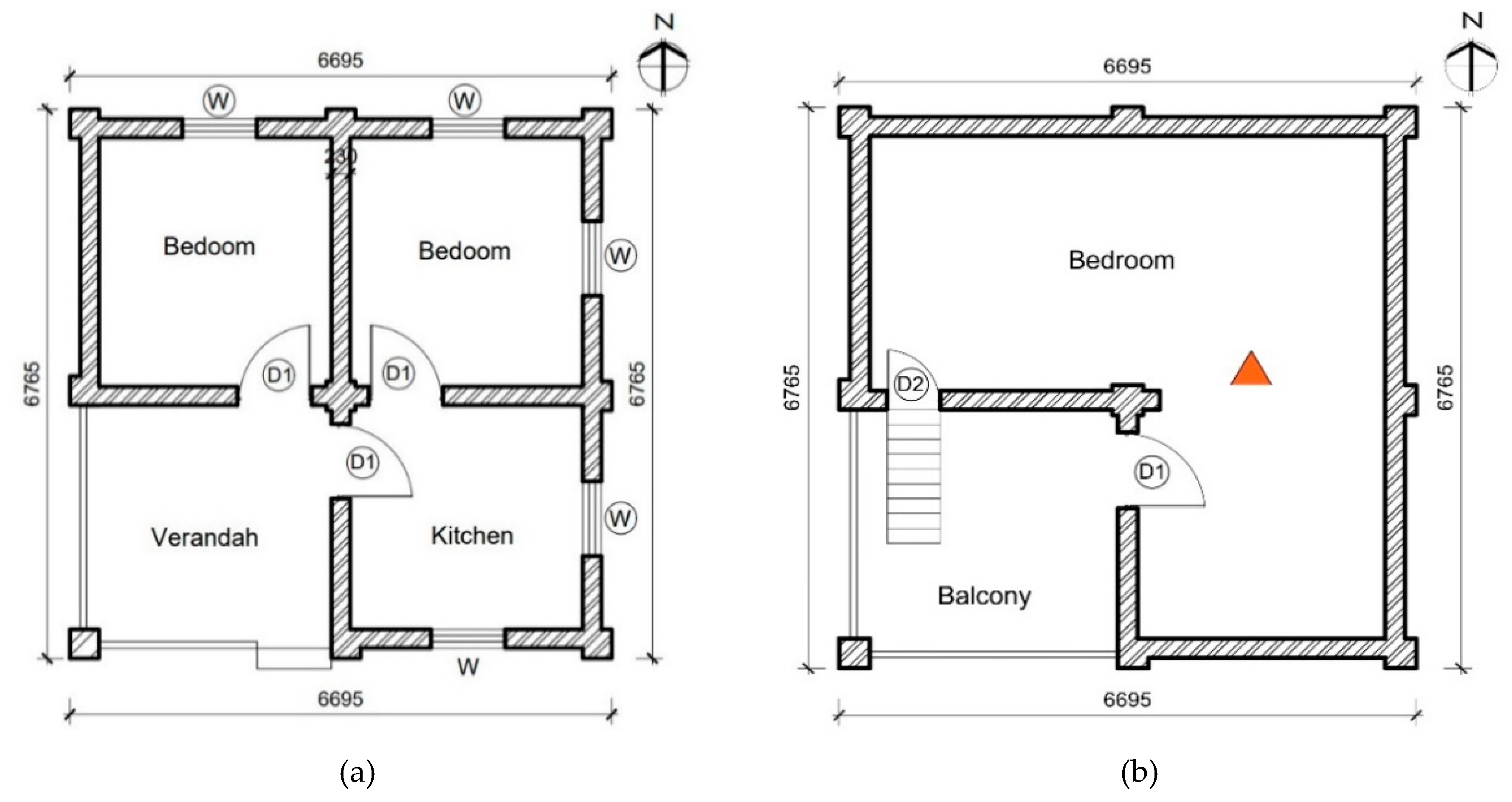

2.1.1. Pre-Disaster Settlement and Housing

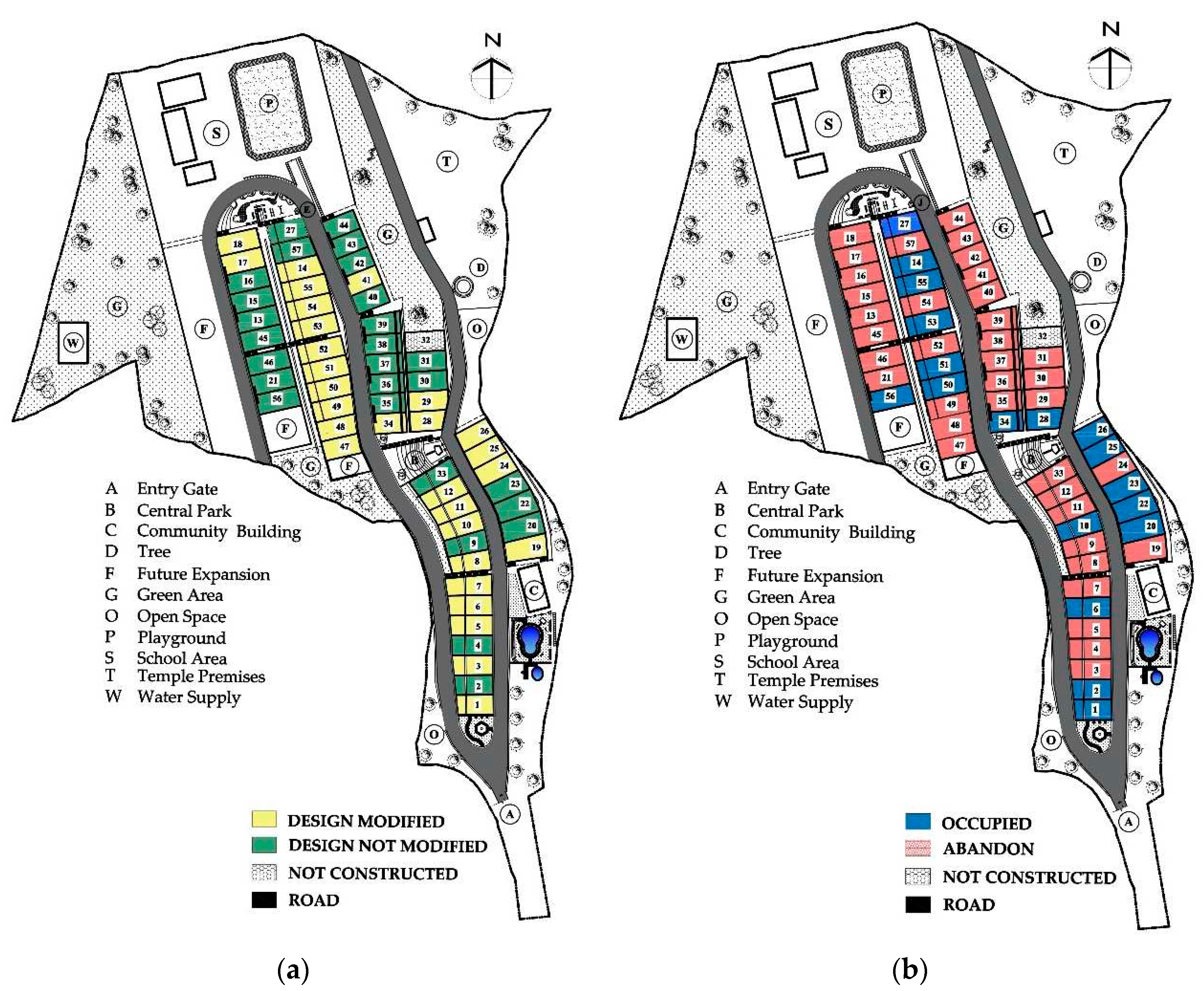

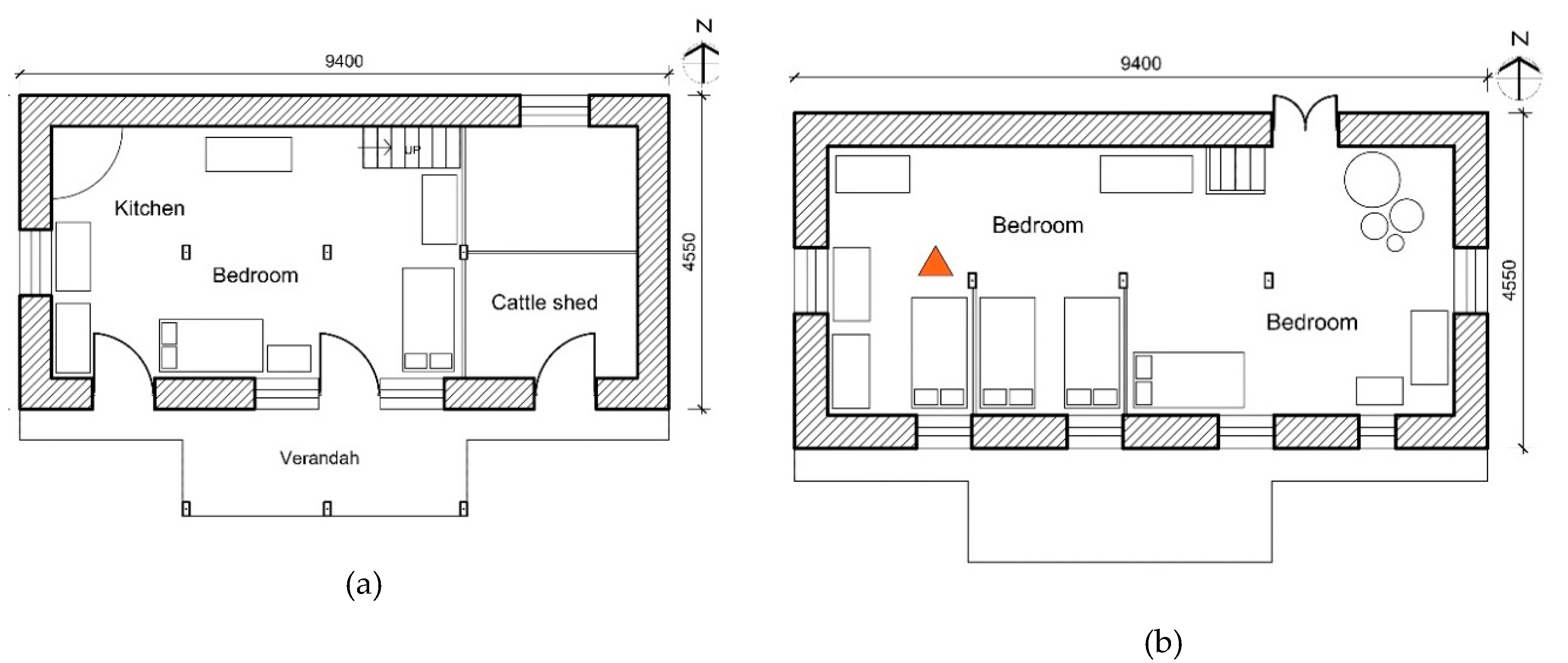

2.1.2. Post-Disaster Settlement and Housing

3. Results

3.1. Respondents of the Survey

3.2. Satisfaction with the Housing

3.3. Factors of Residential Satisfaction

3.3.1. Typical Design as per Need

“In the time of festivals, we have to go back to our old house as the new house has only a limited number of rooms to accommodate our extended family.”

3.3.2. Layout of Housing

“We could have improved the layout of the house by including a passage. In the absence of the passage, we have to pass through a room to go to the inner room, and this has created a difficulty for us.”

“If I could have visualized the drawing, I would have made several corrections in the existing layout. Out of many, one thing that I would have swapped is the position of the kitchen and room. We were used to the old houses, but this house is different than our old house in Bosimpa.”

3.3.3. Space for Addition/Modification

3.3.4. Provision of the Kitchen Garden

“In the absence of a kitchen garden, it is difficult even to get the vegetables. We don’t have a market nearby, and thus, we have to go to Bosimpa every day for the vegetables…even to get the chilies.”

3.3.5. Provision of Cattle Shed

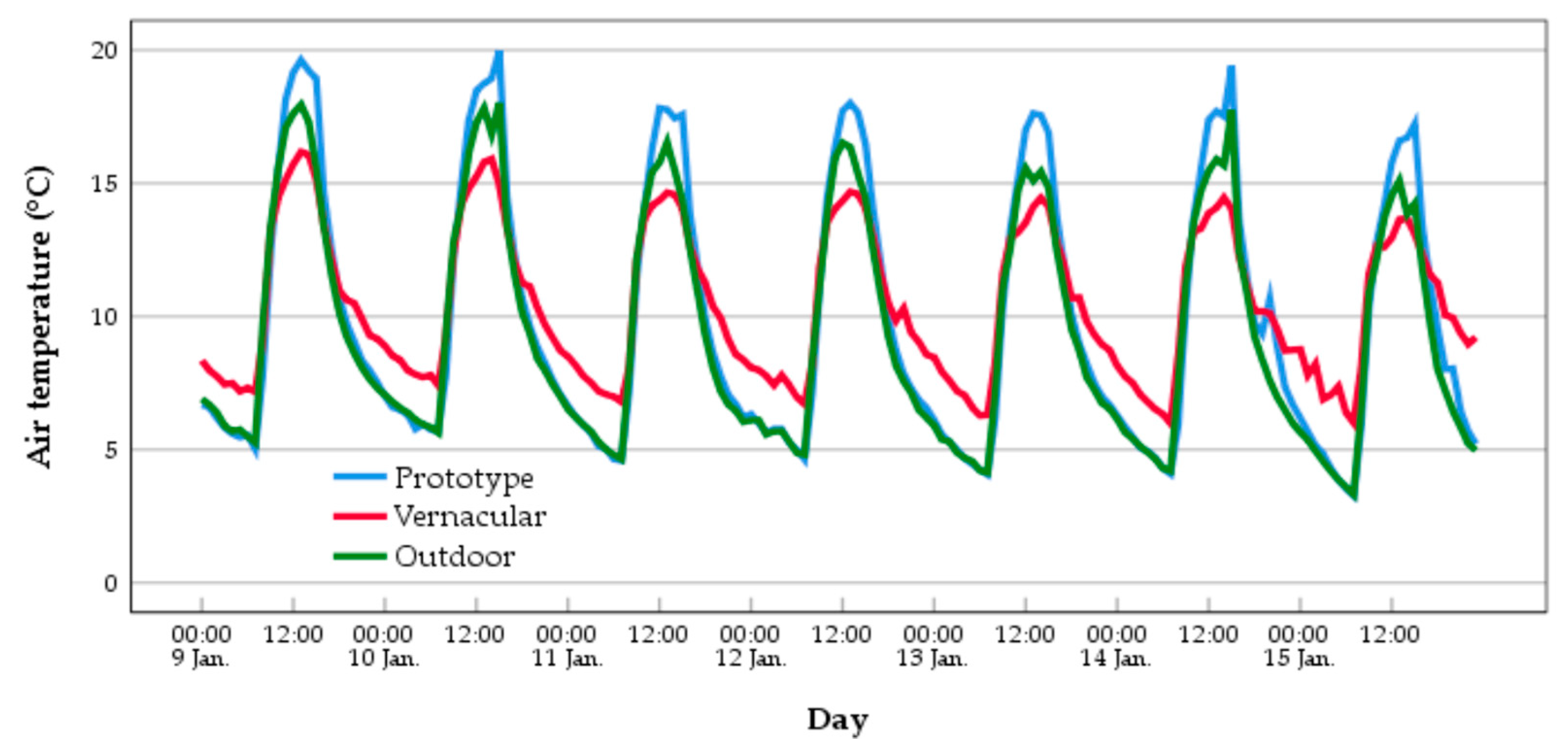

3.3.6. Thermal Comfort

3.1.7. Level of Completeness of the House

“The grant of 2310 USD was not sufficient for housing construction, so we were forced to take a loan for the construction. In the lack of financial capacity and lack of collateral to take a loan, many households could not complete the construction in time.”

3.3.8. Provision of a Traditional Hearth

3.3.9. Ritual Spaces

“The hearth is very important to conduct our birth and death ritual. We don’t have it in our house. In the absence of it, we have to perform our rituals differently, and we may lose our culture.”

“I might someday use the central column for performing the rituals we carried out in our king post and ‘bampa’ that had a cultural and religious significance in our life. For that, I will have to remove some walls to make space for circumambulation around the central column.”

3.3.10. Spaces for Social and Cultural Events

“We are happy with the community center…I gave the party of my son’s wedding in the hall, where I invited all my relatives from this village and also neighboring places….. As the guests were not required to be invited to the house, so the rooms were also not messed up by the event.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The geo hazard assessment by NRA categorized land into CAT 1, 2 and 3. CAT 3 refers to land category which were assessed as unsafe for settlement and thus the households required to be relocated to safer areas.. |

References

- IDMC. Grid 2022; Geneva, 2022.

- Gaillard, J. C. Post-Disaster Resettlement. In People’s response to disasters in the Philippines; 2015.

- Sridarran, P.; Keraminiyage, K.; Amaratunga, D. Enablers and barriers of adapting post-disaster resettlements. In Procedia Engineering; 2018; Vol. 212. [CrossRef]

- Manatunge, J. M. A.; Abeysinghe, U. Factors Affecting the Satisfaction of Post-Disaster Resettlers in the Long Term: A Case Study on the Resettlement Sites of Tsunami-Affected Communities in Sri Lanka. Journal of Asian Development 2017, 3(1), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, N.; Elias-Ozkan, S. T. Housing after disaster: A post occupancy evaluation of a reconstruction project. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2016, 19, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettige, S.; Haigh, R.; Amaratunga, D. Community level indicators of long term disaster recovery. Procedia Engineering 2018, 212, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sey, Y.; Tapan, M. Report on Shelter and Temporary Housing Problem after Disaster; 1987.

- Oo, B. L.; Sunindijo, R.; Lestari, F. Users’ Long-Term Satisfaction with Post-Disaster Permanent Housing Programs: A Conceptual Model. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology 2018, 9(1), 28–32. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Home Affairs; Disaster Preparedness Network-Nepal. Nepal Disaster Report 2015; 2015. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/1293600-World-Disasters-Report-2015_en.pdf.

- NRA. Post Disaster Needs Assessment; 2015.

- National Planning Commission. Post Disaster Needs Assessment Vol A: Key Findings; Kathmandu, 2015. 2015. [CrossRef]

- NRA. Geological Survey Report/ Data Base; Kathmandu, 2020.

- Mohit, M. A.; Raja, A. M. M. A. K. Residential satisfaction-Concept, theories and empirical studies. Planning Malaysia 2014, 12(September), 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, N.; Cosgun, N.; Tas, M. A qualitative evaluation of the after earthquake permanent housings in Turkey in terms of user satisfaction-Kocaeli, Gundogdu Permanent Housing model. Building and Environment 2007, 42(9), 3418–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N. T.; Keraminiyage, K.; DeSilva, K. K. Long-term satisfaction of post disaster resettled communities: The case of post tsunami – Sri Lanka. Disaster Prevention and Management 2016, 25(5), 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. da. Lessons from Aceh: Key Considerations in Post-Disaster Reconstruction. Practical Action Publishing 2010, No. January, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Tafti, M. T.; Tomlinson, R. Best practice post-disaster housing and livelihood recovery interventions: Winners and losers. International Development Planning Review 2015, 37(2), 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijegunarathna, E. E.; Wedawatta, G.; Prasanna, L. J.; Ingirige, B. Long-term satisfaction of resettled communities: An assessment of physical performance of post-disaster housing. Procedia Engineering 2018, 212(2017), 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The human right to adequate housing. https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-housing/human-right-adequate-housing#:~:text=Adequate housing must provide more,supply and availability of housing.

- United Nations Development Programme. What are teh Sustainable Development Goals? https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals#:~:text=The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)%2C also known as the,people enjoy peace and prosperity.

- Ophiyandri, T.; Amaratunga, D.; Pathirage, C.; Keraminiyage, K. Critical success factors for community-based post-disaster housing reconstruction projects in the pre-construction stage in Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 2013, 4(2), 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigyasu, R.; Upadhyay, N. Continuity, adaptation, and change following the 1993 earthquake in Marathwada, India. Rebuilding Asia Following Natural Disasters: Approaches to Reconstruction in the Asia-Pacific Region 2016, 81–107. [CrossRef]

- Sphere Association. The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response; 2018; Vol. 1.

- Miyata, S.; Manatunge, J. Knowledge sharing and other decision factors influencing adoption of aquaculture in Indonesia. International Journal of Water Resources Development 2004, 20(4), 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anilkumar, S.; Banerji, H. An Inquiry into Success Factors for Post-disaster Housing Reconstruction Projects: A Case of Kerala, South India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2021, 12(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurum Varolgunes, F. Success Factors for Post-Disaster Permanent Housing: Example of Turkish Earthquakes. Turkish Online Journal of Design Art and Communication 2021, 11(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, F. Housing reconstruction and rehabilitation in Aceh and Nias, Indonesia-Rebuilding lives. Habitat International 2007, 31(1), 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, J.; Attippoe, A. J.; Ankrah, J. Assessment of Residential Satisfaction in the Resettlement Towns of the Keta Basin in Ghana. International Journal Civil Engineering. Construction and Estate Management 2014, 2(3), 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Day, L. L. Choosing a house: The relationship between dwelling type, perception of privacy, and residential satisfaction. Journal of Planning Education and Research 2000, 19(3), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, A. T. Evaluation and Comparison of Post-Disaster Housing in Turkey: Lessons From Ikitelli and Senirkent. The Second Scottish Conference for Postgraduate Researchers of the Built and Natural Environment 2005, 561–571. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, T.; Weerasoori, I.; Karunarathne, H. An Evaluation of Success and Failures in Hambantota, Siribopura Resettlement Housing Program : Lessons Learned. Sri Lankan Journal of Real Estate 2011, No. 06, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith, A. Successes and Failures in Post-Disaster Resettlement. Disasters 1991, 15(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, J. Disaster, Deceptions, Dislocations: Reflections from an Integrated Settlement Project in Nepal; 2021; pp 111–132.

- Aysan, Y.; Oliver, P. Housing and Culture After Earthquakes A Guide for Future Policy Making on Housing in Seismic Areas; Oxford Polytechnic, 1987.

- Coburn, A. W.; Leslie, J. D. L.; Tabban, A. Reconstruction and Resettlement 11 Years Later: A Case Study of Bingo1 Province, Eastern Turkey. Earthquake Relief in Less Industrialized Areas 1984, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberger, J. The German Red Cross in the earthquake zone of Turkey: regions of Van and Erzurum. In Earthquake relief in less industrialized areas. International symposium; 1984; pp 29–42.

- He, L. Identifying local needs for post-disaster recovery in Nepal. World Development 2019, 118, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, K. Multi-hazards, displaced people’s vulnerability and resettlement: Post-earthquake experiences from Rasuwa district in Nepal and their connections to policy loopholes and reconstruction practices. Progress in Disaster Science 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoon, J.; Gerkey, D.; Chhetri, R. B.; Rai, A.; Basnet, U. Navigating multidimensional household recoveries following the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. World Development 2020, 135, 105041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, D. E.; Koseoglu, E.; Bilen, O.; Der, V. The effect of user participation in satisfaction: Beyciler after-earthquake houses in Düzce. A|Z ITU Journal of Faculty of Architecture 2010, 7(1), 18–37.

- Barenstein, J. E. D. Continuity and change in housing and settlement patterns in post-earthquake Gujarat, India. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 2015, 6(2), 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, S.; Ochiai, C.; Okazaki, K. Residential satisfaction and housing modifications: A study in disaster-induced resettlement sites in Cagayan de Oro, Philippines. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 2017, 8(2), 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, N.; Elias-ozkan, S. T. Post-Disaster Housing in Rural Areas of Turkey Based on. Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences 2005, No. September.

- Enginoz, E. A Model For Post-Disaster Reconstruction: The Case Study in Dinar-Turkey. International Conference and Student Competition on post-disaster reconstruction 2006, No. January.

- Wagner, W. E. Using IBM SPSS Statistics for Research Methods and Social Science Statistics; SAGE Publications, Inc., 2015.

- Ibem, E. O.; Aduwo, E. B. Assessment of residential satisfaction in public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria. Habitat International 2013, 40, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizenga, C.; Zagreus, L.; Arens, E.; Lehrer, D. UC Berkeley Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) Title Measuring indoor environmental quality: a web-based occupant satisfaction survey Publication Date Measuring Indoor Environmental Quality: A Web-based Occupant Satisfaction Survey. 2003.

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival. 2001, p 295.

- DLPIU-Dolakha. Reconstruction Progress Report of Dolakha Distrct Upto April 2022; Dolakha, 2022. 20 April.

- Shneiderman, S.; Turin, M. Revisiting Ethnography, Recognizing a Forgotten People: The Thangmi of Nepal and India. Studies in Nepali History and Society 2006, 11(1), 97–181. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, S. B. Rituals of ethnicity: Migration, mixture, and the making of Thangmi identity across Himalayan borders. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 2009, 123(10), 2114. 2114.

- Bukvic, A.; Smith, A.; Zhang, A. Evaluating drivers of coastal relocation in Hurricane Sandy affected communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2015, 13, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatunge, J.; Takesada, N. Long-term perceptions of project-affected persons: A case study of the Kotmale Dam in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Water Resources Development 2013, 29(1), 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, S.; Turin, M. Thangmi, Thami, Thani? Remembering A Forgotten People. Niko Bacinte Smarika 1993, No. January 2004, 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Boen, T.; Jigyasu, R. Cultural Considerations for Post Disaster Reconstruction Post-Tsunami Challenges. UNDP Conferences 2005 2005, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bouraoui, D.; Lizarralde, G. Centralized decision making, users’ participation and satisfaction in post-disaster reconstruction: The cas of Tunisia. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 2013, 4(2), 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capell, T.; Ahmed, I. Improving post-disaster housing reconstruction outcomes in the global south: A framework for achieving greater beneficiary satisfaction through effective community consultation. Buildings 2021, 11(4). [CrossRef]

- KamacI-Karahan, E.; Kemeç, S. Residents’ satisfaction in post-disaster permanent housing: Beneficiaries vs. non-beneficiaries. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 73(August 2021), 102901. 20 August. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, X. Influence of housing resettlement on the subjective well-being of disaster-forced migrants: An empirical study in yancheng city. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13(15). [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Shen, L.; Tan, C.; Tan, D.; Wang, H. Critical determinant factors (CDFs) for developing concentrated rural settlement in post-disaster reconstruction: A China study. Natural Hazards 2013, 66(2), 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Determinants of villagers’ satisfaction with post-disaster reconstruction: Evidence from surveys ten years after the Wenchuan earthquake. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10(September), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, J.; Wijegunarathne, E.; Wedawatta, G. Study on key performance indicators to investigate long-term performance of post-disaster housing. 2016, 226–234.

- Setiadi, A.; Andriessen, A.; Anisa, R. Post-occupancy evaluation of Pagerjurang permanent housing after the Merapi volcanic eruption. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 2020, 44(2), 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sararit, T.; Tamiyo, K.; Maly, E. Resident’s satisfaction to relocated Houses after 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, Thailand. Procedia Engineering 2018, 212(2017), 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H. N.; Few, R. Social risks and challenges in post-disaster resettlement: The case of Lake Nyos, Cameroon. Journal of Risk Research 2012, 15(9). [CrossRef]

- Badri, S. A.; Asgary, A.; Eftekhari, A. R.; Levy, J. Post-disaster resettlement, development and change: A case study of the 1990 Manjil earthquake in Iran. Disasters 2006, 30(4), 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snarr, D. N.; Brown, E. L. User Satisfaction With Permanent Post-Disaster Housing: Two Years After Hurricane Fifi in Honduras. Disasters 1980, 4(1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, R. S. Designing culturally responsive built environments in post disaster contexts: Tsunami affected fishing settlements in Tamilnadu, India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2013, 6, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, B.; Egbu, C. POST-DISASTER RECONSTRUCTION PROJECTS. 2011, No. September, 889–898.

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A. Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. What does the future hold for relocated communities post-disaster? Factors affecting livelihood resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 34, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoon, J.; Hunter, C. E.; Gerkey, D.; Chhetri, R. B.; Rai, A.; Basnet, U.; et al. Anatomy of disaster recoveries: Tangible and intangible short-term recovery dynamics following the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, 51, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, R. S. Understanding the role of culture in the post disaster reconstruction process The Case of Tsunami Reconstruction in Tamilnadu, Southern India, University of Leading the Way Westminster, 2011.

| Personal Factor | Number | Proportion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 33 | 71.7% |

| Female | 13 | 28.3% | |

| Age | 15-29 years | 3 | 6.5% |

| 30-44 years | 15 | 32.6% | |

| 45-59 years | 13 | 28.3% | |

| Above 59 years | 15 | 32.6% | |

| Marital status | Married | 44 | 95.7% |

| Unmarried | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Widowed | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Family size | 4.07 | ||

| Education level | Illiterate | 20 | 43.5% |

| Basic (I-VIII) | 21 | 45.6% | |

| Secondary (IX-XII) | 5 | 10.9% | |

| Occupation | Agriculture/ Livestock | 24 | 52.2% |

| Labor | 6 | 13.0% | |

| Business | 5 | 10.9% | |

| Service | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Masons/ carpenter | 1 | 2.2% | |

| Remittance | 2 | 4.3% | |

| Others | 7 | 15.2% | |

| Household expenditure per month (NPR) | 15000 | ||

| Household income per month (NPR) | 20000 | ||

| Single women | Yes | 6 | 13.0% |

| Person with disability | Yes | 9 | 19.6% |

| Number of school-going children | 44 | 95.7% | |

| Foreign employment | Yes | 6 | 13.0% |

| Cattle | Yes | 31 | 67.4% |

| The original place of settlement | Bosimpa | 30 | 65.2% |

| Buma | 15 | 32.6% | |

| Others | 1 | 2.2% |

| Factors | Mean | N | RII | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent/earthquake-resistant house | 4.30 | 46 | 0.86 | 1 |

| Modern house style | 3.85 | 46 | 0.77 | 2 |

| Quality of construction material | 3.50 | 46 | 0.70 | 3 |

| New construction material | 3.37 | 46 | 0.67 | 4 |

| Provision of sanitation facilities | 3.26 | 46 | 0.65 | 5 |

| Feeling of privacy | 3.22 | 46 | 0.64 | 6 |

| Daylight inside room | 3.20 | 46 | 0.64 | 7 |

| Ventilation | 3.09 | 46 | 0.62 | 8 |

| Spaces for social and cultural events | 2.57 | 46 | 0.51 | 9 |

| Spaces for performing religious practices and festivals | 2.52 | 46 | 0.50 | 10 |

| Spaces for everyday activities | 2.37 | 46 | 0.47 | 11 |

| Number of sleeping rooms | 2.26 | 46 | 0.45 | 13 |

| Spaces for birth and death rituals | 2.24 | 46 | 0.45 | 14 |

| Size of bedroom and kitchen | 2.22 | 46 | 0.44 | 15 |

| Typical design as per need | 2.11 | 46 | 0.42 | 16 |

| Layout of house | 2.09 | 46 | 0.42 | 17 |

| Provision of drinking water | 2.00 | 46 | 0.40 | 18 |

| Provision of cattle shed | 1.96 | 46 | 0.39 | 19 |

| Level of completeness of the house | 1.91 | 46 | 0.38 | 20 |

| Thermal comfort | 1.87 | 46 | 0.37 | 21 |

| Provision of space for a traditional hearth | 1.83 | 46 | 0.37 | 22 |

| Space for addition/ modification of house | 1.78 | 46 | 0.36 | 23 |

| Plot size | 1.76 | 46 | 0.35 | 24 |

| Provision of the kitchen garden | 1.46 | 46 | 0.29 | 25 |

| Factors | Housing Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Correlation Coefficient | Sig. | |

| Plot size | 46 | .538** | 0.000 |

| Typical design as per need | 46 | .708** | 0.000 |

| Modern house style | 46 | -0.036 | 0.812 |

| Permanent/earthquake-resistant houses | 46 | -0.089 | 0.557 |

| Size of bedroom and kitchen | 46 | .474** | 0.001 |

| Number of sleeping rooms | 46 | .442** | 0.002 |

| Layout of house | 46 | .748** | 0.000 |

| Spaces for everyday activities | 46 | .594** | 0.000 |

| Addition/ modification of house | 46 | .709** | 0.000 |

| Provision of the kitchen garden | 46 | .674** | 0.000 |

| Provision of cattle shed | 46 | .671** | 0.000 |

| New construction material | 46 | 0.280 | 0.060 |

| Quality of construction material | 46 | .323* | 0.029 |

| Level of completeness of the house | 46 | .803** | 0.000 |

| Thermal comfort | 46 | .632** | 0.000 |

| Ventilation | 46 | 0.108 | 0.474 |

| Daylight inside room | 46 | -0.228 | 0.128 |

| Feeling of privacy | 46 | .379** | 0.009 |

| Provision of a traditional hearth | 46 | .729** | 0.000 |

| Spaces for birth and death rituals | 46 | .775** | 0.000 |

| Spaces for performing religious practices and festivals | 46 | .605** | 0.000 |

| Spaces for social and cultural events | 46 | .651** | 0.000 |

| Provision of drinking water | 46 | .434** | 0.003 |

| Provision of sanitation | 46 | 0.208 | 0.166 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).