Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

05 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

2.4. Notification Data

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Health-Related Description of the Study Population

3.2. Seroprevalence of Viral Hepatitis

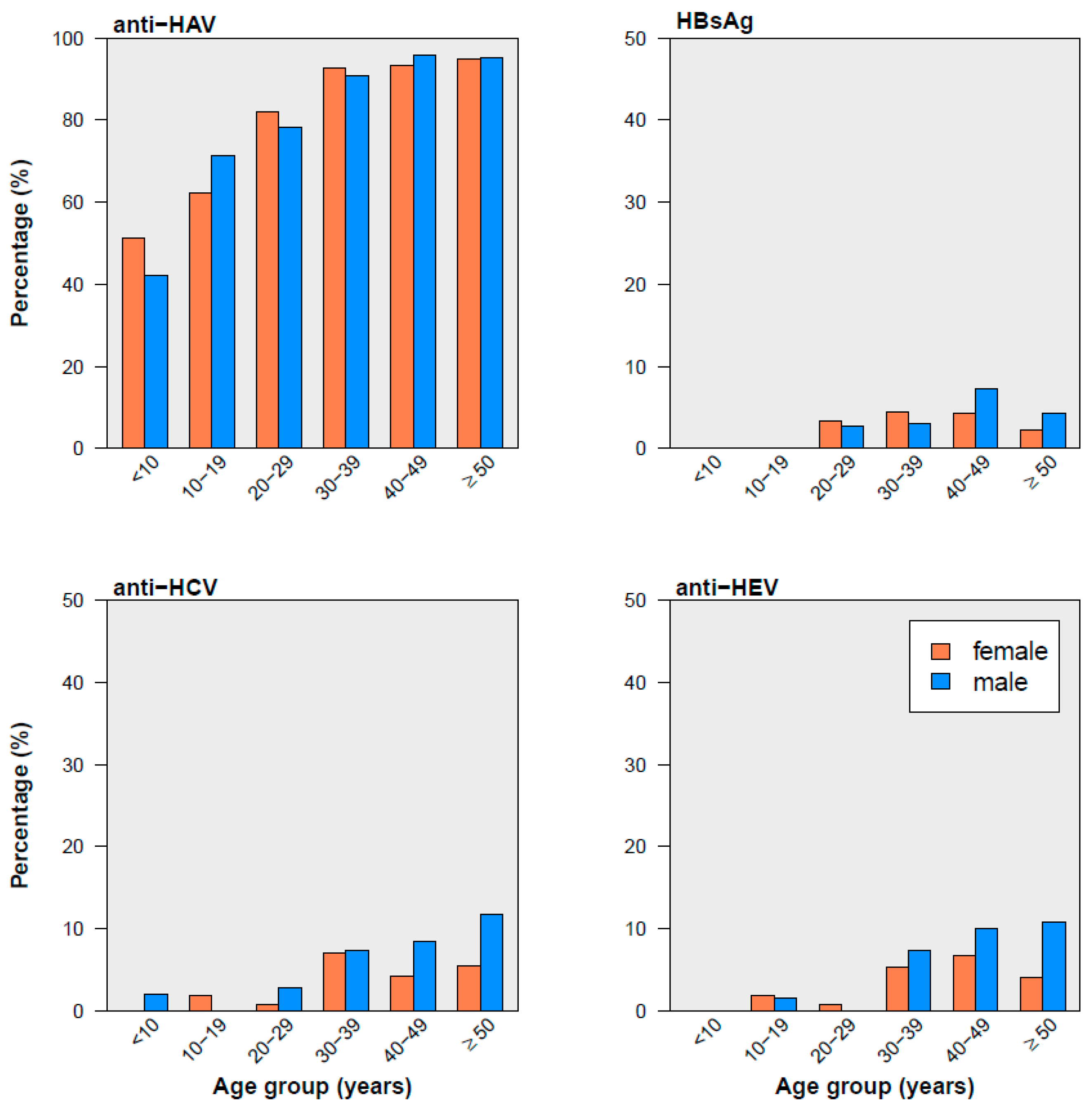

3.3. Seroprevalence by Sex, Age and Ethnicity

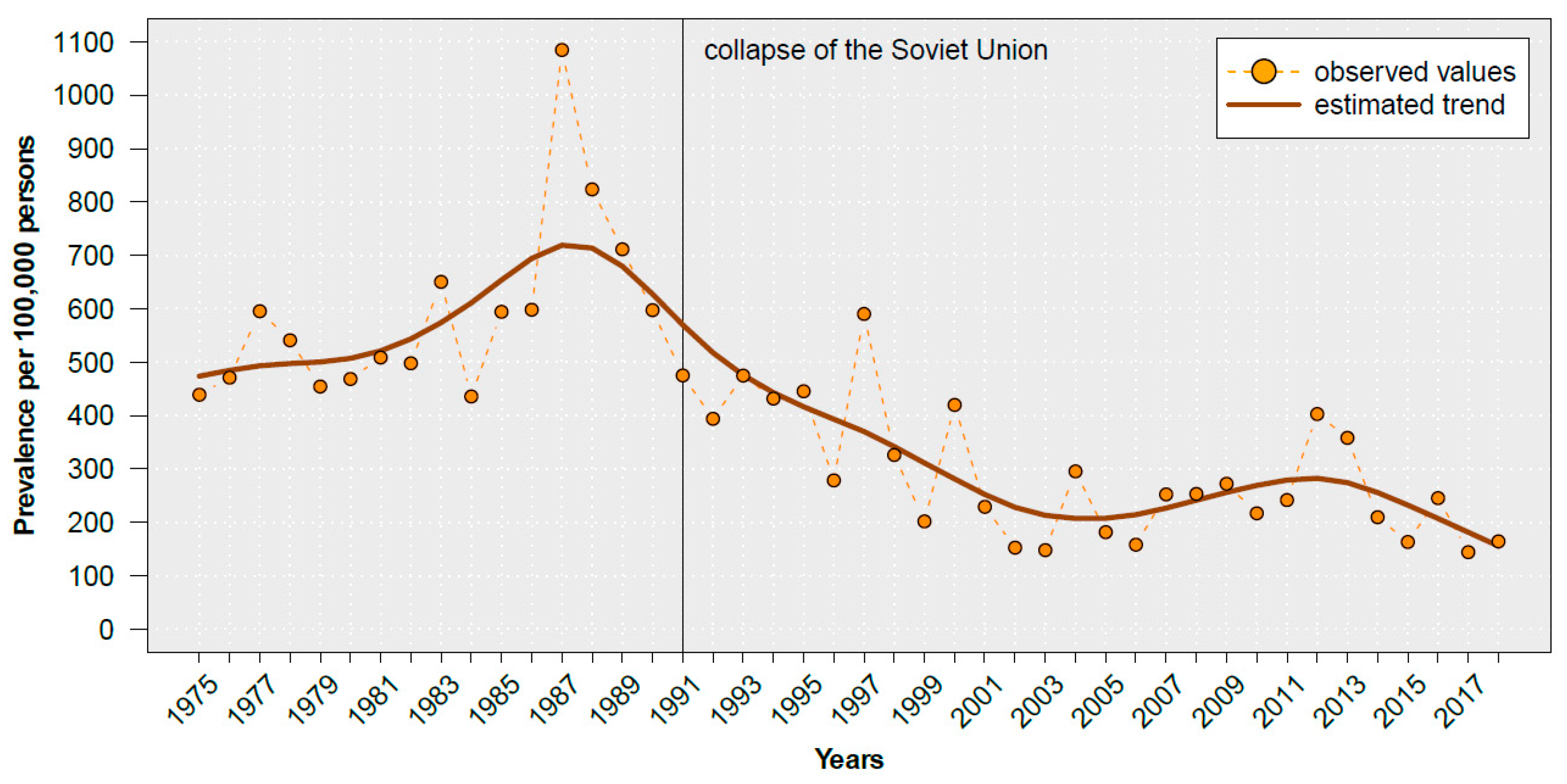

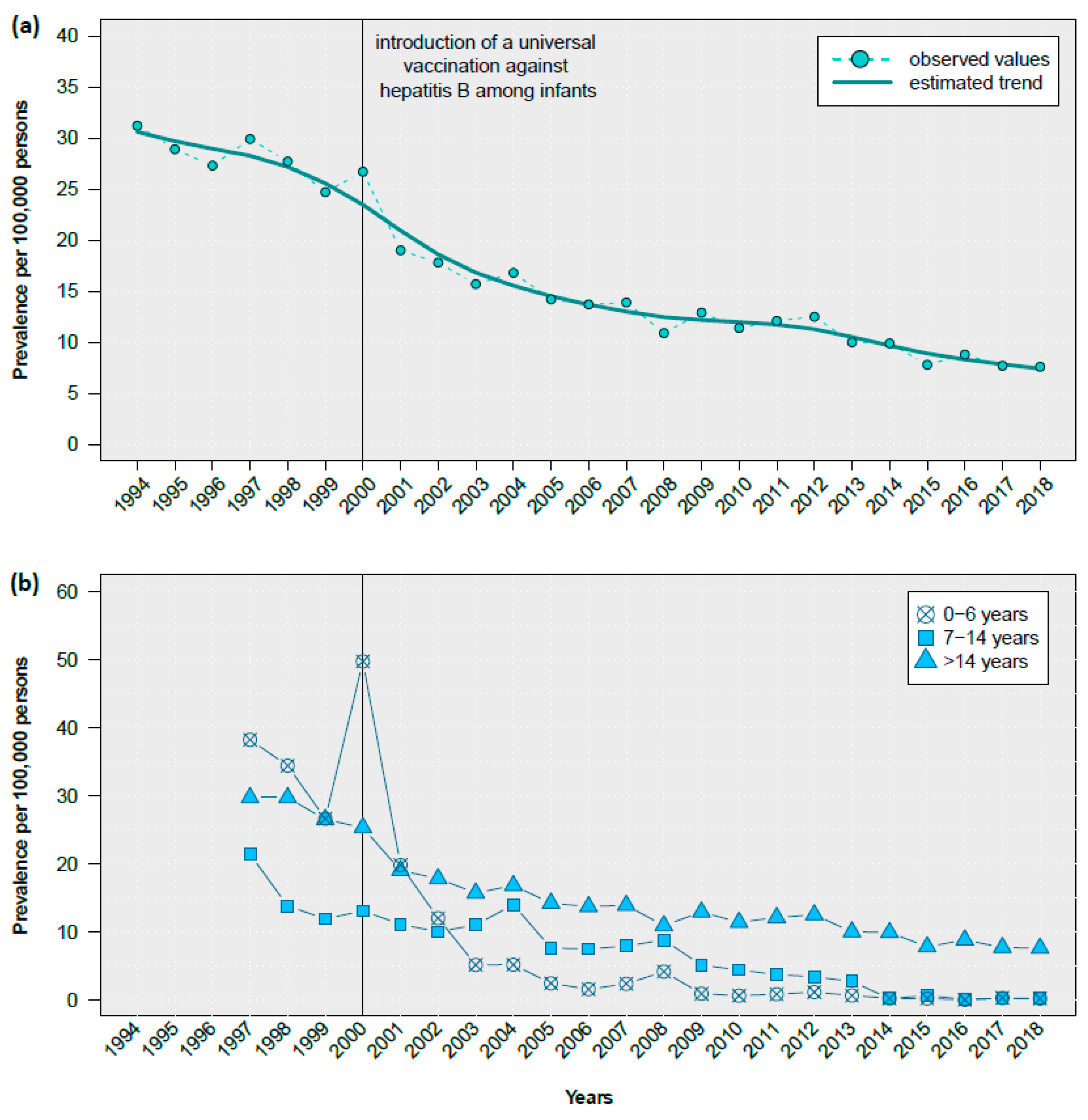

3.4. Notification Data

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jefferies, M.; Rauff, B.; Rashid, H.; Lam, T.; Rafiq, S. Update on global epidemiology of viral hepatitis and preventive strategies. World J Clin Cases 2018, 6, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozalevskis, A., Harmanci, H., and Bobrik, A. Assessment of the viral hepatitis response in Kyrgyzstan: 11-15 July 2016: mission report. Copenhagen: World Health Organization 2016.

- Toichuev, R.; Leybman, E.; Omorbekova, C.; Rakhimova, G.; Zhumabek Kyzy, B.; Nikolaeva, L. Childhood Hepatitis in Osh Province of Southern Kyrgyzstan. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol 2014, 4, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, K.H. Globalization and the Changing Epidemiology of Hepatitis A Virus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8, a031716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, A.; Horn, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Krause, G.; Ott, J.J. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iashina, T.L.; Favorov, M.O.; Shakhgil’dian, I.V.; Firsova, S.N.; Eraliev, A.E.; Zhukova, L.D.; Reznichenko, R.G. [The prevalence of the markers of viral hepatitis B and delta among the population in regions differing in the level of morbidity]. Vopr Virusol 1992, 37, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karabaev, B.B.; Beisheeva, N.J.; Satybaldieva, A.B.; Ismailova, A.D.; Pessler, F.; Akmatov, M.K. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus, Treponema pallidum, and co-infections among blood donors in Kyrgyzstan: a retrospective analysis (2013-2015). Infect Dis Poverty 2017, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Hanafiah, K.; Groeger, J.; Flaxman, A.D.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botheju, W.S.P.; Zghyer, F.; Mahmud, S.; Terlikbayeva, A.; El-Bassel, N.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Central Asia: Systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regression analyses. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karetnyi Iu, V.; Dzhumalieva, D.I.; Usmanov, R.K.; Titova, I.P.; Litvak Ia, I.; Balaian, M.S. [The possible involvement of rodents in the spread of viral hepatitis E]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol 1993, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Onishchenko, G.G.; Favorov, M.O.; L'vov, D.K. , L. [The prevalence and etiological structure of viral hepatitis in a climatic-geographic area at high risk for infection] in Russian. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol 1992, 11-12, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R; Gandhi, S. The global prevalence of hepatitis E virus infection and susceptibility: a systematic review. World Health Organization 2019.

- Sievers, C.; Akmatov, M.K.; Kreienbrock, L.; Hille, K.; Ahrens, W.; Gunther, K.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Obi, N.; Michels, K.B.; Fricke, J.; et al. Evaluation of a questionnaire to assess selected infectious diseases and their risk factors: findings of a multicenter study. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2014, 57, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castell, S.; Akmatov, M.K.; Obi, N.; Flesh-Janys, D.; Nieters, A.; Kemmling, Y.; Pessler, F.; Krause, G. Test-retest reliability of an infectious disease questionnaire and evaluation of self-assessed vulnerability to infections: findings of Pretest 2 of the German National Cohort. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2014, 57, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgyz Ministry of Health. Monthly bulletin for infectious and parasitis diseases. Department of Disease Prevention and Infectiosu Disease Surveillance. Available online: https://dgsen.kg/category/deyatelnost/upravluenie-profilaktiki-infekcionnY/ezhemesYachnYj-bjuleten-sjesizn. [accessed 5 Feb 2023].

- Schweitzer, A.; Akmatov, M.K.; Krause, G. Hepatitis B vaccination timing: results from demographic health surveys in 47 countries. Bull World Health Organ 2017, 95, 199–209G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maistat, L.; Kravchenko, N.; Reddy, A. Hepatitis C in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: a survey of epidemiology, treatment access and civil society activity in eleven countries. Hepatol Med Policy 2017, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedemeyer, H.; Manns, M.P. Epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of hepatitis D: update and challenges ahead. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010, 7, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, R.; Krawczynski, K. Hepatitis E: an overview and recent advances in clinical and laboratory research. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000, 15, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhverchyk, L.N.; Alatortseva, G.I.; Nesterenko, L.N.; Nurmatov, Z.Sh.; Baiyzbekova, Zh.A.; Kasymov, O.T.; Mikhailov, M.I.; Zverev, V.V. Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence among different age groups of the healthy population in Kyrgyzstan. Epidemiol Vacc Prevent 2016, 15, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. The World by Income and Region. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html. [accessed 5 Feb 2023].

| Characteristics | Study Population N=1,075 |

General Kyrgyz Populationa N=6,256,730 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) |

Percent (%) |

Number (n) |

Percent (%) |

|

| Sex | ||||

| male | 495 | 46.0 | 3,101,817 | 49.6 |

| female | 580 | 54.0 | 3,154,913 | 50.4 |

| Age groups | ||||

| <10 years | 92 | 8.6 | 1,464,911 | 23.4 |

| 10-19 years | 123 | 11.4 | 1,051,453 | 16.8 |

| 20–29 years | 230 | 21.4 | 1,129,040 | 18.0 |

| 30-39 years | 209 | 19.4 | 915,167 | 14.6 |

| 40-49 years | 199 | 18.5 | 663,643 | 10.6 |

| ≥50 years | 222 | 20.7 | 1,032,516 | 16.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Kyrgyz | 850 | 79.1 | 4,587,430 | 73.3 |

| Russian | 128 | 11.9 | 352,960 | 5.6 |

| Uzbek | 16 | 1.5 | 918,262 | 14.7 |

| Kazakh | 14 | 1.3 | 35,541 | 0.6 |

| Ujgur | 11 | 1.0 | 57,002 | 0.9 |

| other | 7 | 0.7 | 305,535 | 4.9 |

| Diabetes mellitusb | ||||

| yes | 14 | 1.3 | NA | NA |

| no | 1045 | 97.2 | NA | NA |

| don’t know | 16 | 1.5 | NA | NA |

| Myocardial infarctionb | ||||

| yes | 9 | 0.8 | NA | NA |

| no | 1057 | 98.3 | NA | NA |

| don’t know | 9 | 0.8 | NA | NA |

| Asthmab | ||||

| yes | 8 | 0.7 | NA | NA |

| no | 1057 | 98.3 | NA | NA |

| don’t know | 10 | 0.9 | NA | NA |

| Cancerb | ||||

| yes | 9 | 0.8 | NA | NA |

| no | 1055 | 98.1 | NA | NA |

| don’t know | 11 | 1.0 | NA | NA |

| Rheumatoid arthritisb | ||||

| yes | 34 | 3.2 | NA | NA |

| no | 1026 | 95.4 | NA | NA |

| don’t know | 15 | 1.4 | NA | NA |

| Self-perceived health statusb | ||||

| poor | 51 | 4.7 | NA | NA |

| fair | 122 | 11.3 | NA | NA |

| good | 45 | 4.2 | NA | NA |

| very good | 674 | 62.7 | NA | NA |

| excellent | 183 | 17.0 | NA | NA |

| Hepatitis | Unweighted Total Number of Study Participantsa | Number of Study Participants with Seropositive Resultsa | Crude Proportion of Study Participants with Seropositive Results a | Weighted Total Number of Study Participantsb | Weighted Proportion of Study Participants with Seropositive Results b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N) | (n) | (% (95% CI)) | (N) | (% (95% CI)) | |

| HAV | 986 | 824 | 83.6 (81.1–85.8) | 996 | 75.3 (72.5–77.9) |

| HBV | 1074 | 33 | 3.1 (2.2–4.3) | 1073 | 2.2 (1.5–3.3) |

| HCV | 1074 | 51 | 4.7 (3.6–6.2) | 1073 | 3.8 (2.8–5.1) |

| HDV | 1004 | 6 | 0.60 (0.27–1.30) | 1017 | 0.40 (0.15–1.01) |

| HEV | 1065 | 47 | 4.4 (3.3–5.8) | 1062 | 3.3 (2.4–4.5) |

| Variables | HAV AOR (95% CI) |

HBV AOR (95% CI) |

HCV AOR (95% CI) |

HEV AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| male | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| female | 1.08 (0.74–1.58) | 0.88 (0.44–1.77) | 0.51 (0.29–0.93) | 0.66 (0.36–1.20) |

| Age (change per one year increase) | ||||

| 1.08 (1.06–1.09) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Kyrgyz | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Russian | 0.21 (0.12–0.35) | 0.43 (0.10–1.84) | 2.39 (1.19–4.80) | 0.22 (0.05–0.96) |

| other | 0.37 (0.21–0.65) | 1.46 (0.50–4.29) | 0.91 (0.27–3.05) | 0.48 (0.11–2.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).