1. Introduction

People diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have significant difficulties with social interaction skills, such as eye contact, responding to their name, and difficulty understanding social stimuli (e.g., facial expressions, body language, changes in the inflection of language). According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD, 2010), about 25% of people with ASD are unable to use language naturally to communicate. These deficits tend to persist throughout life [

1]; however, improvements are possible when early and intensive behavioral interventions (EIBI) are implemented [

2] and the treatment is customized to suit individual’s needs [

3].

Alternative Augmentative Communication (AAC) tools offer communication forms that may make it easier for children with ASD to communicate than traditional forms such as spoken language. Three forms of AAC used with children with ASD include unaided approaches (e.g., signs and gestures), low-tech image-based systems (e.g., PECS), and "hi-tech" speech-generating device (SGDs) systems [

4].

AAC tools must be individualized to the needs of the users. For this reason, Blackstone et al., (2007) [

5] suggested that prerequisite skills required for any AAC form take into account and matched to the child’s strengths. The effectiveness of an AAC method also depends on the ability to customize the tool with which the child will interact. Furthermore, they recommend that the communicative context, as well as the communicative goals, should be considered when selecting an AAC device. Thus, the choice of an appropriate AAC system may be considered one of the most important aspects of language intervention. Several studies indicate that for children with

ASD, the most effective AAC tools are PECS and SGD [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], some recent studies underlined the preference for technological tools such as tablet device as more engaging for children [

11].

During the PECS training, the student is instructed to deliver an image to a communication partner that corresponds to the item he wishes to obtain [

7]. With SGD, instead of exchanging an image, the student learns to touch or drag an icon, depicting the desired object, on the screen of an electronic device, which produces a recorded message structured in the following form: "I want " [

12].

The PECS system was originally designed to increase spontaneous requests. However, several studies have shown additional positive effects. As many studies showed that treatment focused on communicative skills are the strategies of choice for reducing problem behavior [

13], also Charlop et al. (2002) [

14] reported a decrease, and in some cases complete elimination of the problem behaviors, after the implementation of the PECS. In the same study, the beneficial effects of PECS on different communicative and social behaviors (e.g., eye contact, joint attention, and shared play) were demonstrated. Other studies have also shown positive effects of the PECS system on spontaneous linguistic production [

14,

15]. Some authors [

16,

17,

18] concluded that PECS is the best method for increasing a mand repertoire, as well as other communication skills.

On the other hand, SGDs are devices designed to produce recorded or synthesized vocal outputs. They are designed to accommodate a variety of configurations that allow for customization and individualization, which is particularly helpful for students with severely limited language skills [

19].

Many SGD studies demonstrated an increase in manding skills [

12,

20,

21,

22,

23], while a few studies demonstrated a more general increase in vocal production [

24,

25] or other communicative and social interaction skills [

26]. Data from Schlosser and Wendt (2008) [

18] revealed that SGDs can contribute to an increase in the voice production of students. While the increase in language skills is well documented with SGDs, there is little on the effects of SGDs on social interaction skills.

The SGS we used for this study, the Language Interface for AAC Rehabilitation (LI-AR), is a new type of SGD [

27,

28]. Its software creates innovations for teaching social interaction skills. During the training with LI-AR, the vocal output is fully managed by a communication partner/therapist. Through a Bluetooth device, the therapist decides to activate the vocal output only if the student has successfully completed the communication task, approaching the therapist and delivering him the tablet. The external management of vocal output ensures that the training is focused on the prerequisites of communication, in this case the communicative exchange.

Only a few studies have compared the acquisition of manding skills using the PECS and SGD systems and there are only minimal differences between the two systems in terms of ease of use and speed of skill acquisition. For example, Sigafoos et al. (2009) [

26] investigated manding skill acquisition time and preferences for the two types of communication systems. The results showed slight differences in terms of speed of acquisition of the skill, with PECS being slightly more efficient. Two participants showed a preference for the SGD during the first sessions of assessment, but this preference shifted to PECS towards the final stages of the intervention.

Son et al. (2006) [

29] compared the effectiveness, preference and, speed of skill acquisition between SGD and PECS, noting a slight preference for two of the participants who used the PECS system, this preference, however, was not correlated with better performance or faster skill acquisition. Other studies have yielded opposite results, for example, Lorah et al. (2013) [

30] compared the use of the iPad with SGD and the PECS system in 5 preschool students with autism. All study participants acquired communication skills using both tools, but the students produced more independent requests via SGD, and 4 of the 5 participants showed that they preferred it to the PECS system.

According to what has emerged from the data reported so far, most of the studies that have compared the effectiveness of PECS and SGD have focused mainly on the ability to request what is desired, neglecting all the aspects simultaneously involved in verbal behavior as communication prerequisites. An important aspect is the social interaction that underlies each truly communicative act. Communication consists, in fact, in a behavior, defined topographically by the community, directed towards another person who then provides the consequence, verbal behavior can be defined effective only if it includes the mediation of another person [

31].

Social interaction can be defined as the ability to actively initiate and maintain communication with a partner and refraining from other socially inappropriate behaviors [

32,

33]. Effective social interaction requires the integration of different social and communication skills. For example, when a communication exchange begins to obtain a preferred item, it would be socially appropriate for those who use an AAC system to look and orient towards the communication partner, rather than facing the opposite direction. Sigafoos et al., (2009) [

26] observed that there were no significant differences between the effects on the social interaction of training with PECS and SGD, although training with the PECS method required slightly more direct interaction with a communicative partner. This result, however, cannot be considered exhaustive and the aspect should therefore be investigated more thoroughly. This study aims to compare the use of SGD and PECS for teaching manding skills to children with ASD, using a specific AAC software LI-AR for the training procedure with the SGD. Of primary interest in this study is the relative (i) effectiveness; (ii) preference for and, (iii) acquisition time associated with each system. A secondary interest of the study was to evaluate the effect on two additional dependent variables, specifically: (i) increase of communicative ability (e.g., understandable vocalization, word production, sign, pointing, request with SGD or PECS), and (ii) decrease in minor problem behaviors.

2. Method

2.1. Participants.

The study was attended by 3 children aged between 3 and 10 years with an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities of the University of Naples Federico II.

The 3 children had no communicative skills acquired through PECS, nor SGD systems. Participants had communication skills equal to a value of ≤ 2.0 years and fine-motor motor skills equal to a value of 1.0 years, measured though the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS-II) [

34]. Their QI scores ranged between 60 and 85. Laura was a 10-year-old girl. Before the study, she had non-communicative skills, due to verbal dyspraxia that made articulation difficult; however, when the objects were present, she neither tried to reach for or grasp them. Dario was a 4-year-old boy. He did not use language in a functional way, he presented some echolalia of portions of words and generally monosyllabic vocalizations; he had no communication skills through PECS or SGD. Previously, a sign language training had been introduced, but was unsuccessful due to Dario’s propensity for scrolling, and was subsequently discontinued. Marco was a 3-year-old boy. He did not use language in a functional way, but we observed only some echolalia episodes. He did not produce verbal requests and took what he wanted, indicated it or echoed the request that was made to him. Before this study, he had never had experience with any AAC system, nor with any visual- graphic tools including PECS or SGD. In addition, he presented escape and avoidance behaviors, or complaints as a consequence of frustration.

2.2. Experimental Design.

In order to compare the results and verify the onset of a change in the communicative behavior of the participants, a multiple baseline design (MBD) across participants [

35] was used for this study combined with an Adapted Alternating Treatment Design (AATD) [

36]. The MBD allowed the introduction of the treatment at different times, for each of the participants, to assess whether the onset of behavior change coincided with the treatment itself. The AATD has allowed therapists to simultaneously teach the request through the use of both systems, without any interruption.

2.3. Materials and Settings.

The study was conducted in room 5 m by 3 m, in the presence of a therapist and an assistant as a prompter. The room contained a table, and two chairs positioned one in front of the other. The SGD and the PECS book were always present on the table during the sessions, except for the training sessions where only the system trained was present. After the preferred items were defined, they were placed in a transparent container, visible to the child but out of reach.

The SGD training used LI-AR., software for the AAC, installed on an Android Tablet 6.0. The PECS training used a standard PECS book. Each symbol depicted a preferred item. For each participant, we identified a minimum of 5 favorite items, selected by a preference assessment. The Multiple Stimuli Without Replacement procedure was used (MSWO) [

37] to identify the most preferred items. Three equivalent but independent sets of reinforcers were selected and randomly assigned to the condition (SGD/PECS). Communicative behaviors were recorded using a verbal behavior observation form.

2.4. Response Definition and Measurements.

In accordance with the main objective of the study, to evaluate the change in communicative behaviors we recorded the percentage of occurrence of (i) requests, defined as the verbal response to a non-verbal discriminative stimulus, in the absence of a verbal discriminative stimulus [

38]. Furthermore, we considered communicative behavior to be any: (ii) understandable vocalizations, (iii) word production, (iv) pointing, and the (vi) use of an AAC system. The request with an AAC system occurs whenever a participant independently exchanges an image from the PECS notebook or when they use the tablet to obtain the preferred item. These dependent variables were monitored and recorded before, during, and after the training, during the probe sessions. The verbal behavior observation form we used allowed us to record any behavior used to obtain socially mediated reinforcement. Defining topographically any behaviors we could label it as social- communicative behavior or simple motor act. Motor acts are any instrumental use of others’ body, such as grabbing the arm of another person to reach for an object.

In addition to the communicative behaviors, several secondary measures were recorded: (a) the percentage of correct responses to the training (i.e., acquisition speed); (b) the preference of AAC method; (c) changes in minor problem behaviors; (d) change in vocal production. These behaviors were recorded during 10 min sessions divided into 20 intervals of 30 sec. In order to analyze the change in vocal production, we calculated an index of “quality of speech” for each request occasion: 0 points were attributed if no vocalization occurred; 0.5 points for non- functional and not understandable vocalization; 1 point for each vocalization that was functional and understandable, but not completely pronounced (e.g., at least half of the syllables with which the original word is composed); 2 points for understandable and functional vocalization. These scores were attributed to the five request occasions proposed during the probe sessions and an average score for the session was obtained (

Figure 8). A partial interval recording was applied to measure the occurrence of all the measures described above. The observation for the study occurred twice a week during the baseline, during the training phase after every 4 days of training, for the follow-up, as for the baseline twice a week, after 2-month from the end of the training.

2.5. Procedure

At the beginning of the study, a preference assessment was conducted according to the multiple stimulus-without-replacement assessment procedure [

37,

39].

Baseline: During baseline sessions, both systems (PECS and SGD) were placed on the table. The students had the opportunity to requests whenever they wanted, but 5 request opportunities were arranged by the therapist according to a specific procedure. The therapist showed the preferred items to increase the student's motivation operation (MO) and provided a brief period of free access to suspected reinforcers and subsequently blocked access to those items [

40,

41]. The baseline lasted 10 min during which the therapist kept the student engaged in work or play activities and created 5 opportunities to request preferred items, showing the child the most motivating objects, arranged on a tray, positioned to be visible but not reachable by the child. The therapist potentiated the child's MO allowing access for a short period of time and then withholding access. During the 10 seconds following the withholding of reinforcement, then any of the behaviors used to regain access to the reinforcers were recorded. At the end of the 10 seconds, the reinforcers were delivered regardless of the student’s responses.

Training: During the training, the two systems were introduced alternately. Each training phase consisted of three sessions, each with three trials. The decision to start with one of the two conditions was determined randomly for the three participants [

43]. Specifically, as soon as one of the three participants finished the baseline sessions, it was established with which system to start and, consequently, the other participant started, at the end of his baseline, with the opposite system. The training procedure for each tool is explained in detail below.

AAC Preference Assessments/Probe Session: After every 4 days of training (i.e., 2 for PECS, 2 for LI-AR), to prevent sequence effects, the participant was offered the opportunity to choose which communication device with which to work. The session was set-up just as the baseline sessions during which we created 5 request opportunities by the imposition of an EO. The participant had the opportunity to choose to communicate as they preferred. During this session, both AAC tools were available on the table. The therapist asked the child “What do you want?” and then observed which of the two tools they choose. At the end of the session, the therapist started a training session with the most chosen tool and then trained the least tool during the next session.

Follow-up: Two months after the last observation, three probe sessions were proposed to observe the maintenance of the acquisitions. These sessions were arranged as for the baseline.

2.6. Training Procedure

For the PECS training, all the participants experienced the first 3 training phases according to the original PECS protocol [

7], and a fourth phase added for the purposes of this study in which the children were taught to use the PECS book to select a single picture. This was done to make the two procedures comparable. Pictures in this phase were categorically divided within the book on different sheets. We did not teach how to construct more complex sentences. A student’s participation in the training portion of the study ended when they learned to functionally request a single item at a time.

The LI-AR training phase was organized to be comparable to that used for PECS. The prerequisite for training with LI-AR required only the ability to drag an object on a touchscreen. With this device, it is possible to manage pictures and vocal output to encourage the exchange.

The tool provides five distinct phases, in this study, participants attended three of these phases and a fourth phase adapted for the study in which the children were taught to select one picture and the pictures were categorically divided into different pages attainable by swiping from right to left and vice versa on the tablet screen.

Phase I The child is in presence of his major reinforcement. When his motivational operation (MO) is revealed, the therapist prompted the student to drag the image corresponding to the desired item towards the box positioned at the top of the screen, as shown in

Figure 1. This action will produce the vocal output and the student obtains his reinforcer.

Phase II The conditions were the same as in the previous phase, but in this phase, the student learned to “exchange”. The vocal output was produced by an external action of the therapist, only after the child has given the tablet to the therapist. After the student has dragged the image in the right way (

Figure 1), the prompter, positioned behind the student, should prompt to take the tablet and give it to the therapist. After the exchange, the therapist can manage the vocal output through the Bluetooth device, and subsequently, reinforce the student with the chosen item. During this phase, the student learns that the exchange is necessary to obtain the reinforcement.

This phase is divided into two different parts as for phase II of the PECS training. The therapist works on distance and persistence, gradually moving himself and the tablet away from the child.

Phase III The teaching procedure and conditions were the same as in the previous phases.

In this phase pictures showed on the screen were managed by the therapist. Some distractors were randomly presented on the screen (

Figure 2) to teach the discrimination skill, using the corresponding control, as for the PECS procedure.

Phase IV Conditions were the same as in the previous phases. In this phase pictures on the screen were categorically divided into different sheets (

Figure 3). The students were completely free to choose any of the reinforcers following their MO. Each complete exchange was considered functional communication behavior.

3. Results

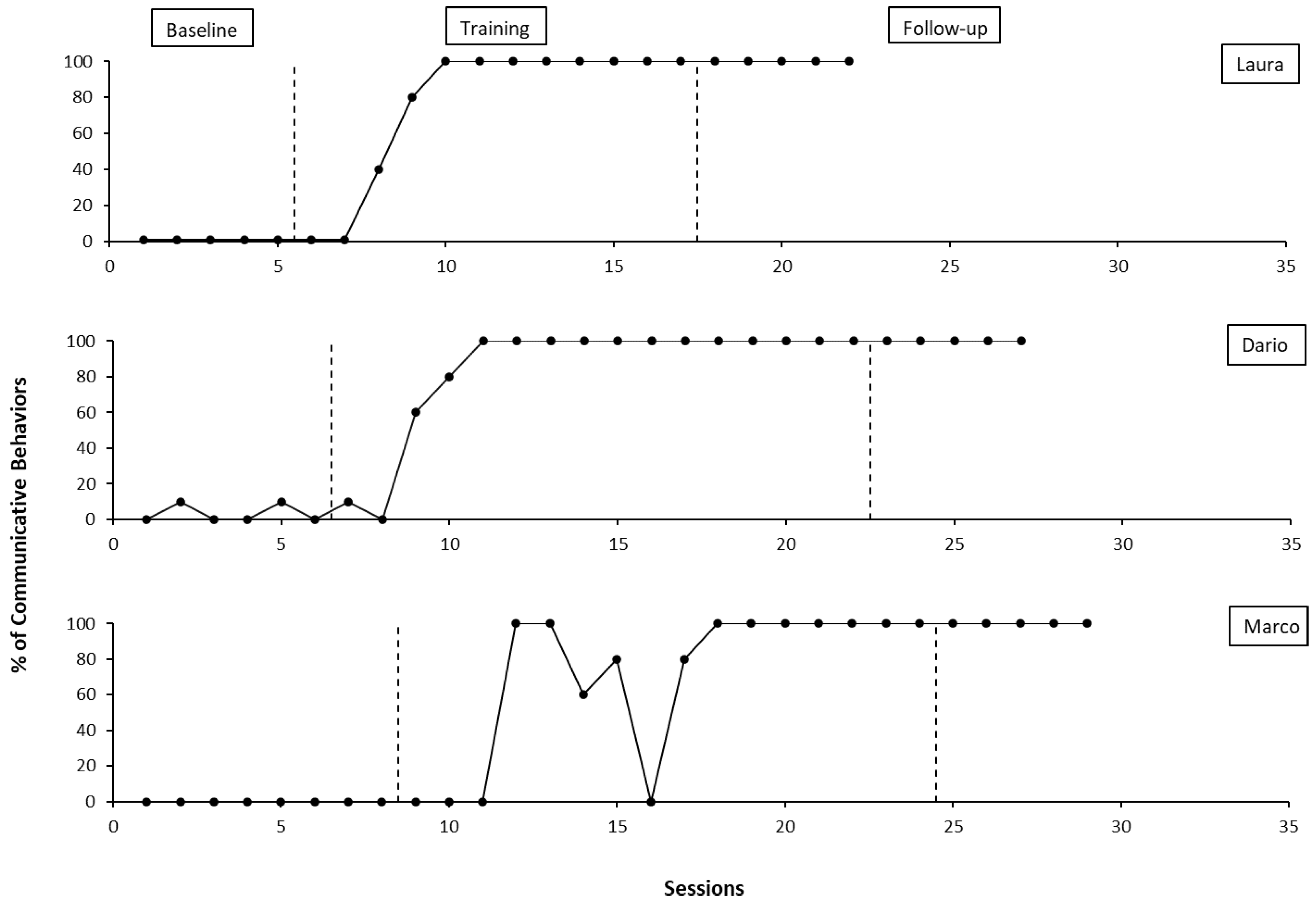

During the baseline (

Figure 4), none of the participants showed functional communicative behaviors. Laura mostly emitted some indistinct complains maybe as request, Marco presented some not understandable vocalizations and few approximations of words. Dario showed disorganized behaviors to get what he wanted by himself. As shown in

Table 1, all the participants showed some attempt to communicate with one of the two systems since the first probe session was presented after the first 4 training sessions. The training gave its effect with a very short latency (

Figure 4).

Laura showed a rapid increase in communicative behavior, she reached 100% of communicative behavior in the middle of the training phase. This percentage was high and stable along with the study. After the training was introduced, she chose to communicate with LI-AR with an average percentage of 95% during the probe session (

Table 1).

Dario also showed a rapid increase in communicative behaviors. He reached 100% of communicative behavior after 4 probe sessions during the training. He showed a preference for LI-AR with a percentage of 88% (

Table 1).

Marco had a more fluctuating and deviant trend compared to the others. At the beginning of the treatment, he did not show any communicative behaviors. After 3 probe sessions during the training period, there was an increase followed by a sharp drop. After this episode the behavior increased, remaining high throughout the study. Marco showed a preference for PECS with a percentage of 53% (

Table 1).

Statistical analysis confirmed the results of the visual inspection. For all the participants it was possible to observe a statistically significant change in the trend of communicative behavior, with a p-value <.001.

These data were analyzed by a second independent observer for 50% of the sessions. An Interval by Interval IOA method showed a accordance of 95%.

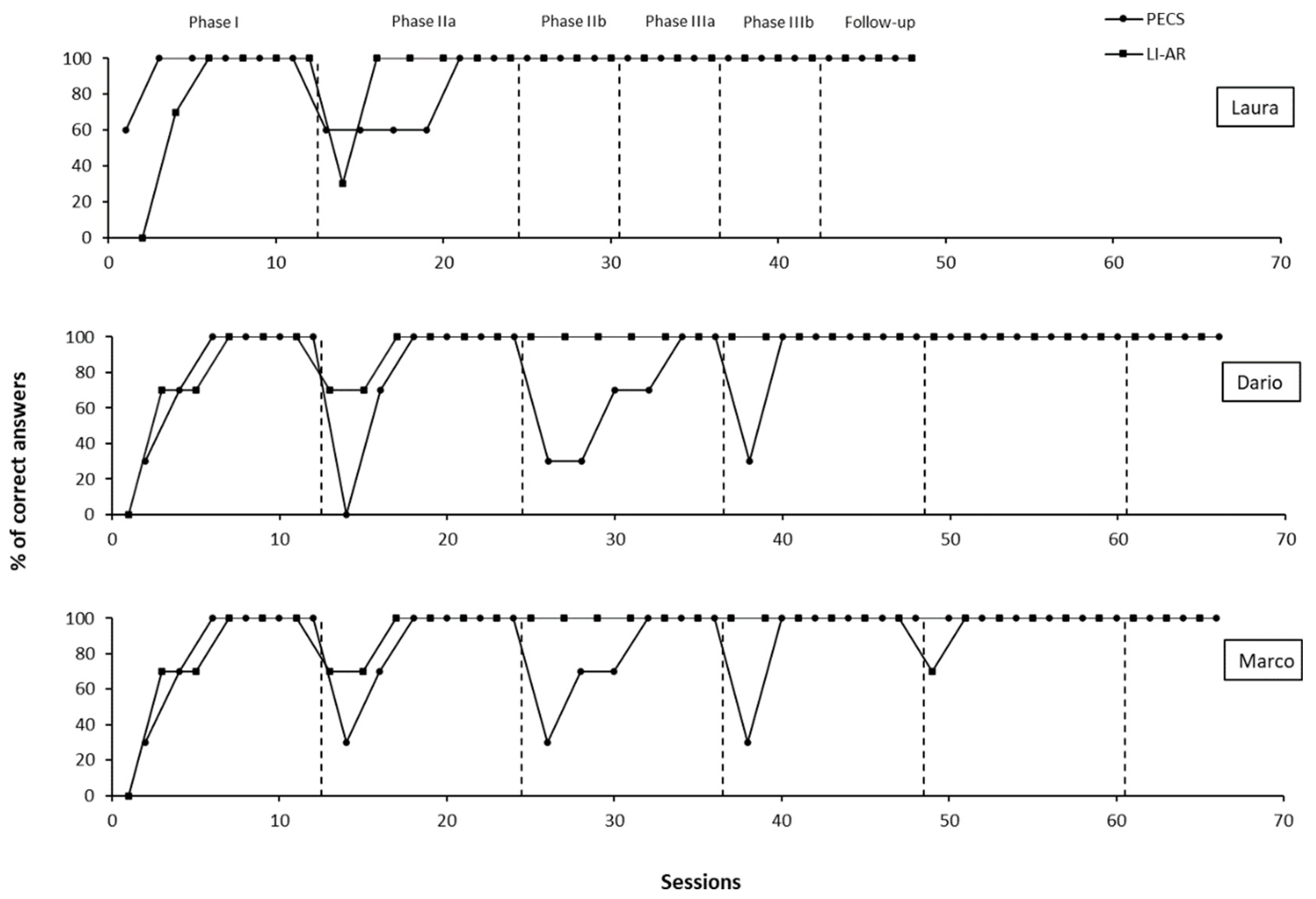

The visual inspection showed that the acquisition criteria for the SGD condition were achieved earlier than the PECS condition (

Figure 5). A consistent downward peak emerged every time the children changed phase with PECS. For the SGD training, a downward peak emerged only for Phase I. The acquisition times are consistent within the students but not between them. In fact, Laura reached the acquisition criteria very quickly (18 LI-AR sessions, 24 PECS sessions). Dario needed 24 training sessions with LI-AR and 30 training sessions of PECS to reach the acquisition criteria. Marco spent 23 training sessions with LI-AR and 27 sessions of PECS training. For all the participants the acquisition criteria for the SGD training was reached faster than the PECS one.

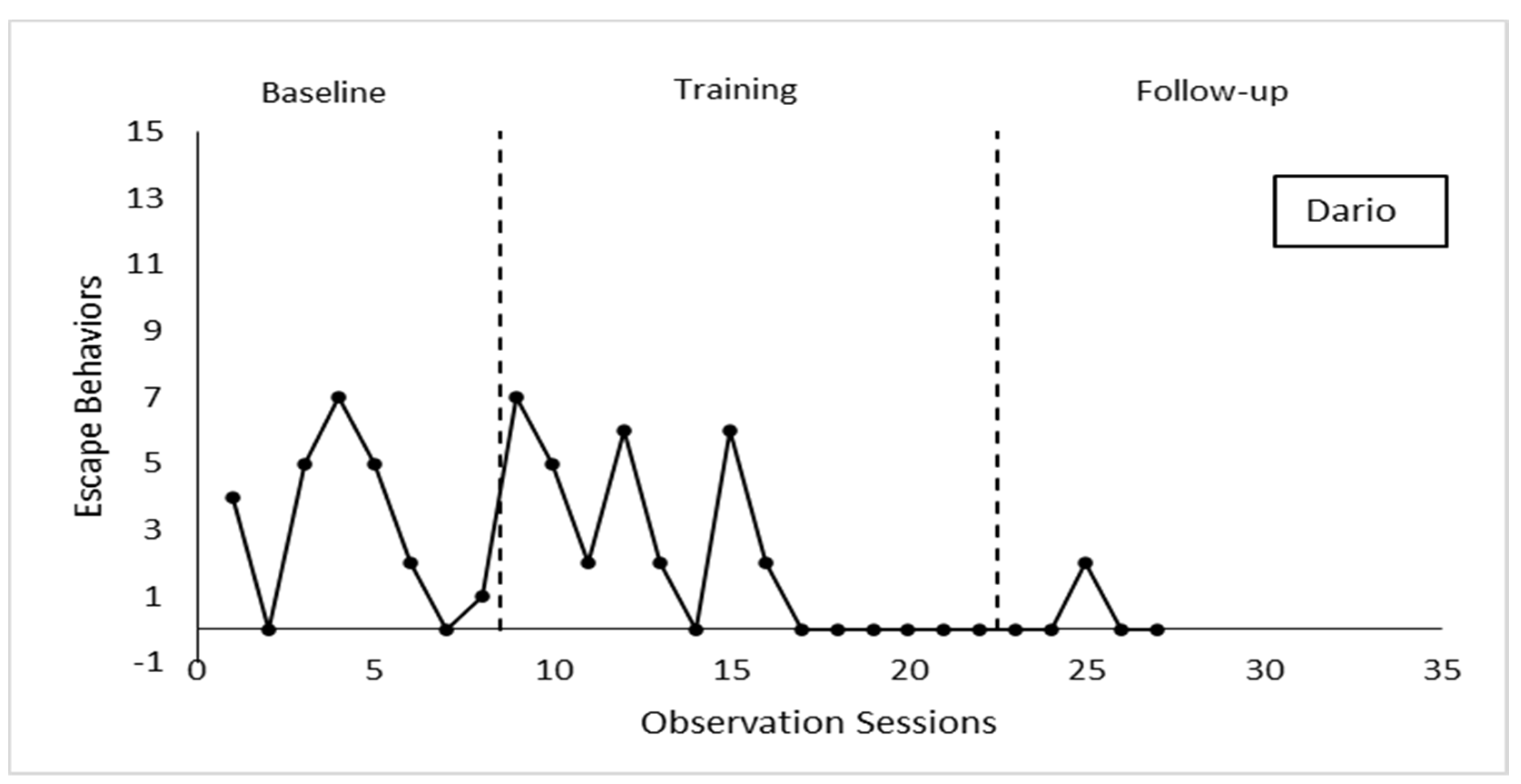

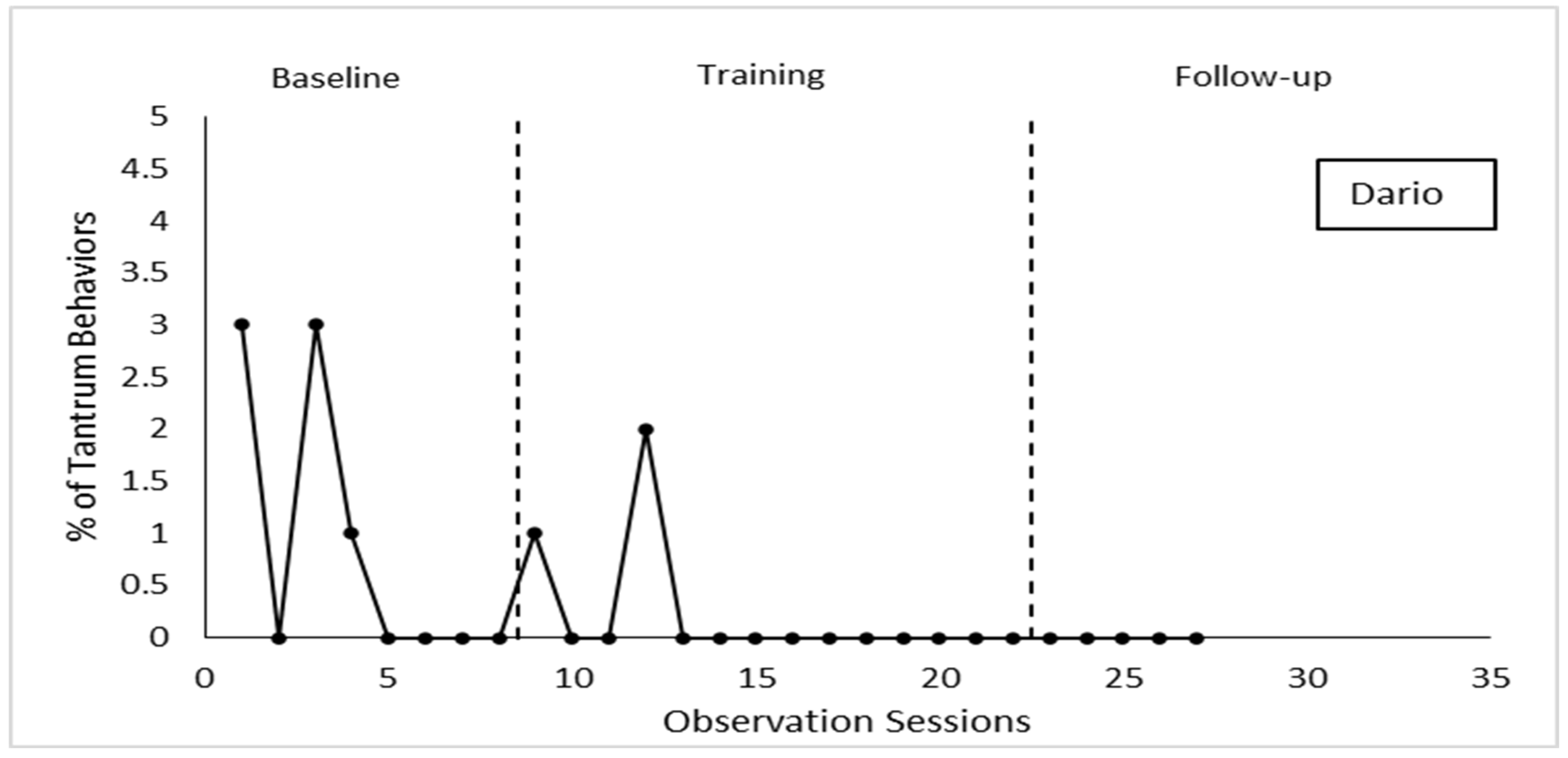

Problem behavior and vocal production were observed for Dario, who was the only one to show hints of understandable vocalization and problem behaviors (e.g., escape and complain) before the study. Escape and complain behaviors were observed separately. The graphs in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 respectively showed the percentage of intervals in which these behaviors occurred.

As shown in

Figure 6 escape behaviors occurred with an average of 3 for session during the baseline, a descendent trend is evident during the treatment with an average of 2.3 per session. During the follow up the occurrence of this behavior reached an average of 0.4.

Tantrum behavior (

Figure 7) occurred with an average per session of 0.87 during the baseline. The trend was descendent, once the treatment was presented, with an average of 0.23 per session during the treatment phase and an average of 0 for the follow-up.

These data were analyzed by a second independent observer for 50% of the sessions. An Interval-by-Interval IOA method shown a accordance of 90%. Statistical analysis showed a significant descendent trend with a p-value of 0.003 for the escape behaviors and <.001 respectively for the tantrum.

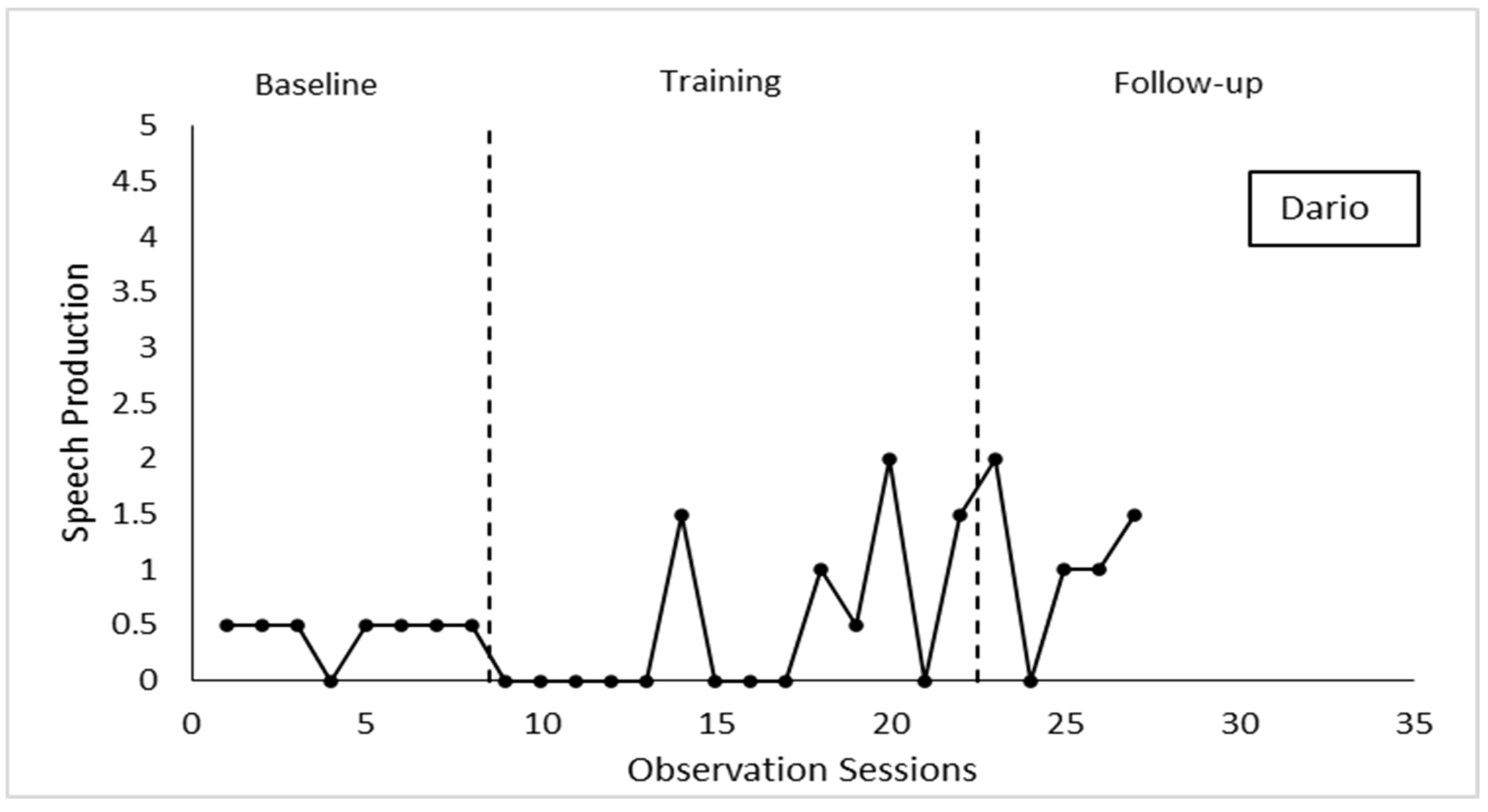

The graph in

Figure 8 shows the trend of Dario's speech productions. The visual inspection revealed that the vocal production increased in terms of quality, from an average of 0.4 during the baseline to 1 point during the follow-up, confirming an improvement in the “quality of speech”. The number of attempts was stable with a slight decrease at the beginning of treatment. In the middle of the treatment, Dario showed, for the first time, understandable and functional vocalization.

These data were analyzed by a second independent observer for 50% of the sessions. An Interval-by-Interval IOA method shown a accordance of 95%.

A t-Student test revealed a p-value of 0.069. in the pre-intervention the maximum score that the child could obtain on the total possibility was equal to 0.66, according to the values established to evaluate its correctness as described above, after training the average of the vocalizations reaches a maximum score of 2, indicating that the child tended to emit more often words that were correct both from a grammatical and functional point of view. In particular, we can observe that at the end of the training phase and in the follow-up, Dario reached an average score of 2 points, which means that speech production was improved in terms of quality.

4. Discussion

The first aim of the study was to determine if children with a diagnosis of ASD could be taught to use PECS and/or an SGD for requesting purposes. The data indicated that both AAC options were acquired for requesting, consistent with the results of previous studies (e.g., [

43]). The second aim concerned the speed of acquisition of requesting skills. All three participants were able to achieve the mastery criterion within a comparable period of time, suggesting that the two AAC options were equally effective to teach communication skills. Two of the three participants showed a higher speed of acquisition with LI-AR system. All the participants reached the acquisition criteria for each LI-AR phase faster than PECS ones and they showed fewer errors at the beginning of a new phase with the SGD (Fig. 5).

The third objective of the study was to assess modality preferences using a variety of techniques. Van der Meer et al. (2012) [

22] noted that a communication system can be considered preferred when it is chosen more often than another option. Preference assessment probes indicated an overall preference for the LI-AR for two of the three participants (

Table 1). Laura and Dario showed a preference for LI-AR and they continued to use this system to communicate after the treatment. Marco’s preference assessment revealed a preference for PECS and he continued to use this tool to communicate after the treatment. The follow-up data indicated that children who continued to use LI-AR as preferred system showed a 100% preference for this tool also during the follow-up. Marco, who preferred PECS during the treatment, decided to use also LI-AR (50%) to communicate during the follow-up, as shown in

Table 1. This can be due to a not real preference of PECS as communication mode. As reported by his therapist, Marco used to stimulate himself with the Velcro behind the PECS, every time he took one, and probably this was the reason why he mostly decided to use PECS previously.

These results clearly contrast with the literature (e.g., [

44]) that showed a faster acquisition and a greater preference for PECS.

The fourth aim of the study concerned whether children with communication problems could improve their vocal production during an AAC training. This study has shown that one of the three participants (Dario) has obtained an improvement in vocal production (

Figure 8). Dario was the only one to show vocalization at the beginning of the study. During the treatment, he acquired the ability to produce whole words, completely understandable. These results revealed that AAC training did not interfere with the development of vocal communication and that instead, it can be extremely useful to improve the quality of speech production. Further studies are needed to confirm these results.

This study indicated also a descendent trend of problem behavior during and after the introduction of the AAC training, confirming the literature (e.g., [

14]) that reported the correlation between the acquisition of communicative skills and the decrease of problem behaviors. Results showed a significant decrease in the frequency of problem behaviors in the second half of the training phase and an almost complete absence in the subsequent follow-up sessions.

However, the data suggested that both PECS and SGD can be considered useful for initial intervention to teach requesting to children with ASD with limited verbal abilities, but further studies are required to confirm these results. Nonetheless, this study extends the existing literature in three ways: it demonstrates that an adapted communication protocol can be successfully used to teach communication through an SGD; children with ASD and few vocal repertoires can improve in speech production through the use of an AAC tool; acquisition of a new modality to communicate may have an effect on the frequency of problem behavior.