Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

05 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Approach

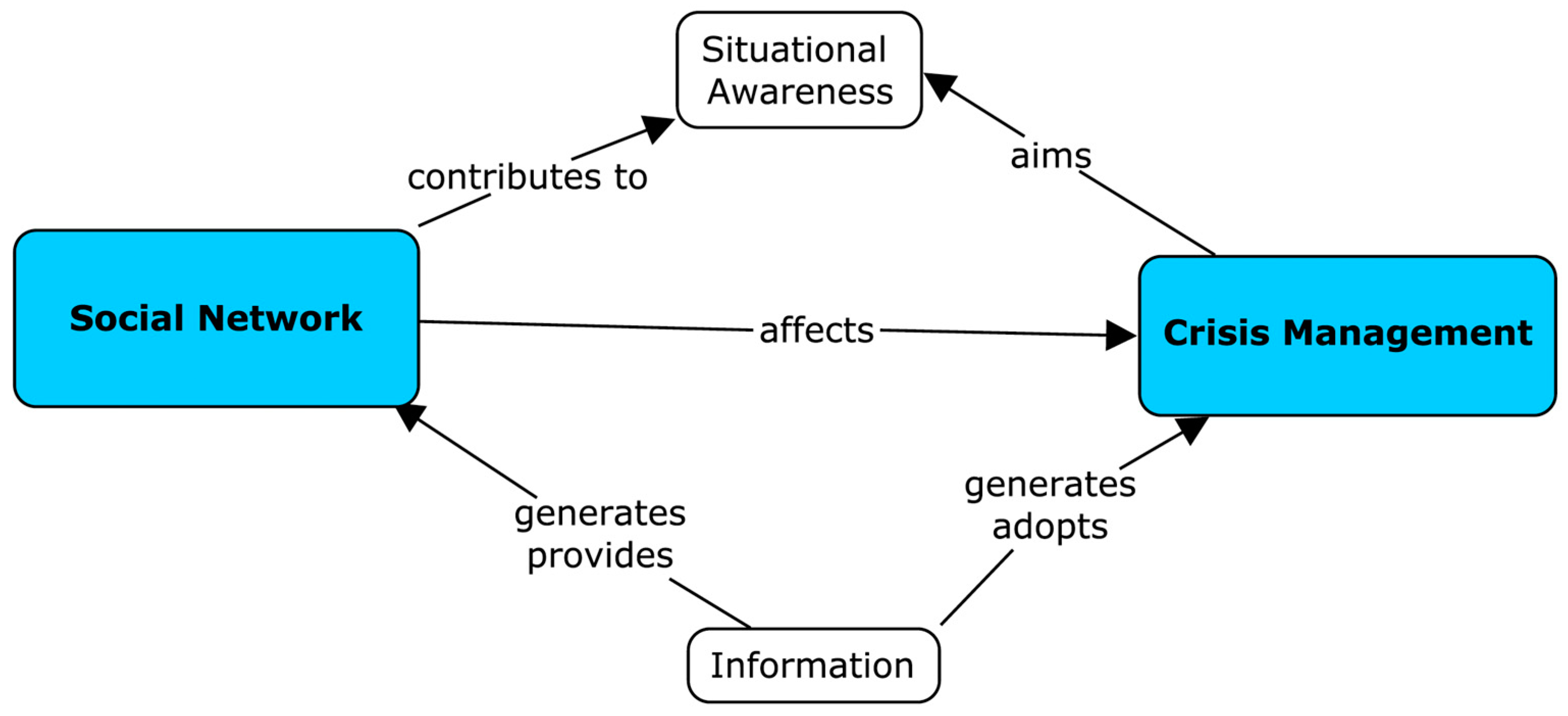

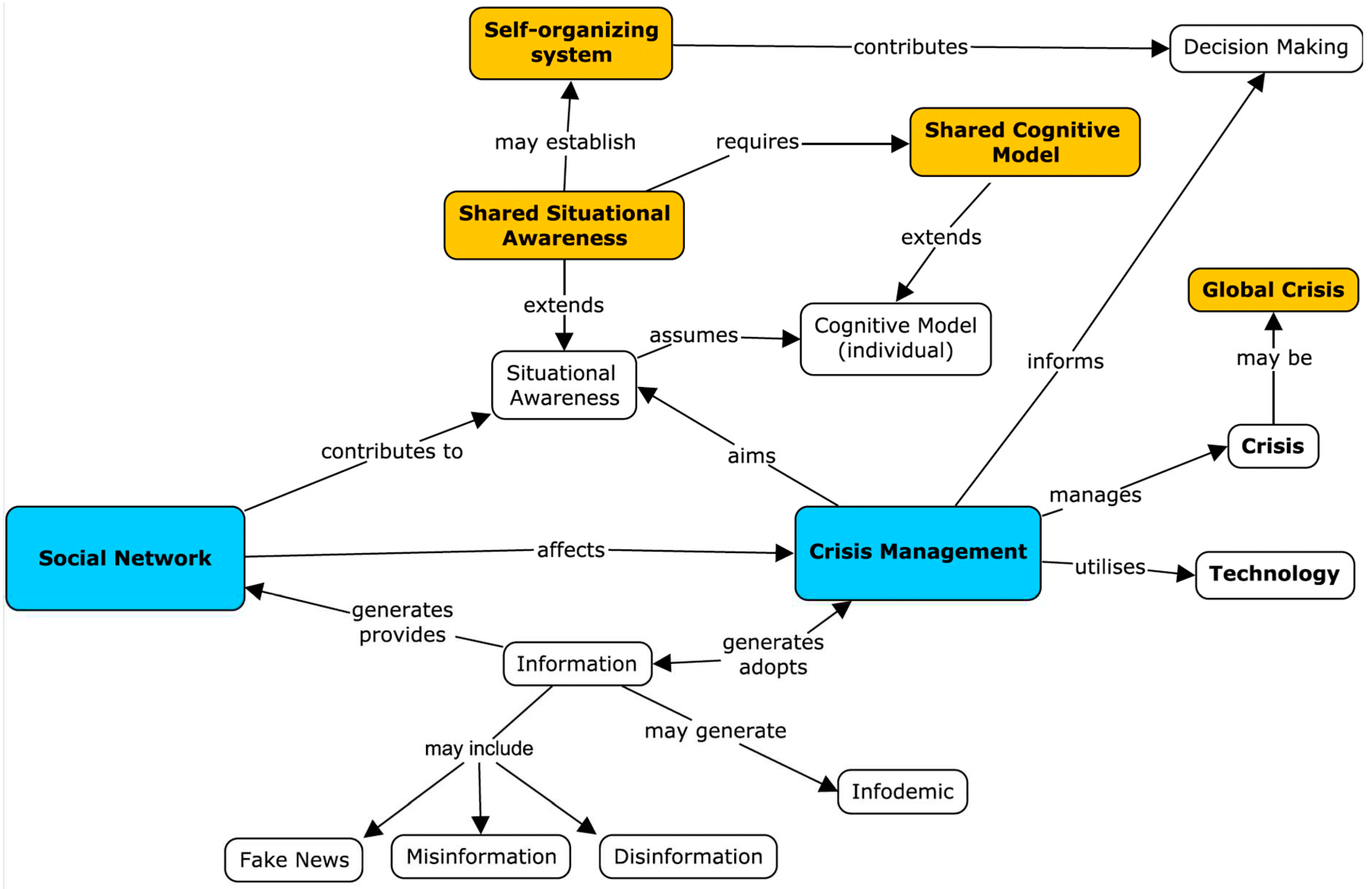

3. Crisis Management & Social Network

3.1. Information, Misinformation/Dis-Information and Fake News

3.2. Managing Information from Social Media

3.3. Situational Awareness

3.4. Crisis Management, Decision Making and Technology

3.5. Datasets

- Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS), containing real-time information about natural disasters, including earthquakes, hurricanes, and floods.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on severe weather events, such as tornadoes, thunderstorms, and hailstorms.

- Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) on mass disasters.

- US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) on federal disaster declarations in the United States.

- Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) on historical weather data , which can be used to study trends in temperature, precipitation, and other climate variables.

- Sentinel-1 Radar Imagery, which provides radar imagery of the Earth’s surface.

- Global Forest Watch Fires on wildfires worldwide.

- In addition, the following datasets are tailored for Social Media related to natural disasters:

- CrisisLex (https://crisislex.org/data-collections.html) includes social media data related to natural disasters, such as tweets, images, and videos, as well as annotations related to the type of crisis and the type of information shared.

- CrisisNLP (https://crisisnlp.qcri.org/) includes social media data related to natural disasters, enriched by annotations and metadata.

- Twitter Crisis Response Data (https://crisislex.org/data-collections.html) includes tweets related to natural disasters, enriched by annotations and metadata.

- Social Media and Emergency Management Data Toolkit (https://tools.emergencymanagement.columbia.edu/) includes multiple datasets that contain data from Social Media related to natural disasters, including tweets and Facebook posts, as well as annotations and metadata.

4. Results

4.1. Conceptualisation of the Literature Review

4.3. Gap Identification and Challenges

- large volume of information exchanged via Social Media [76]

- uncertainty caused by the lack of reliable and trustworthy information [76]

- user-generated contents that don’t meet the trust standards of the emergency agencies [15]

- lack of credibility and trustworthiness in the citizen-generated contents [89]

- lack of competence and knowledge expertise [89]

- lack of sufficient policies and guidelines to use social media [89]

- information overload [92]

- lack of ability to provide timely and accurate information [105]

- lack of expertise to build self-organising systems using social media [89]

| Research Questions | |

|---|---|

| RQ1 | How can a better shared situational awareness be achieved in a crisis management context? |

| RQ1/a | How can the use of social media and AI-based technology change cognitive models to develop a shared situational awareness during crisis? |

| RQ1/b | How can we establish alignment of individual cognitive models and shared situational awareness to support effective crisis management? |

| RQ1/c | What is the expected role of cutting-edge technology in the next generation of systems? |

| RQ2/ | How can effective cognitive models be established during global crisis? |

| RQ2/a | What are the negative aspects of using social networks in a context of infodemic? |

| RQ2/b | How the public interact during the global crisis in term of information seeking and self-organizing? |

| RQ2/c | How can shared mental models be established in a global crisis? |

| Research Gap | Concept | |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | The capability to systematically retrieve information real-time as well as to generate effective analytics and predictive models is still a challenge [18]. | Information Retrieval/Analysis, Analytics, Predictive Models |

| G2 | There is no exhaustive and well-defined analysis of potential impact of cutting-edge technology, especially AI to define the next generation of systems [119]. | Cutting-edge technology, AI, next generation systems |

| G3 | Advanced Analytics and AI based technology are expected to provide a key contribution to establish and safely enable in practice an effective and efficient communication [18,119]. | Advanced Analytics, AI |

| G4 | The well-known effect of Social Networks on dis-information, misinformation and fake news has an evident potentially higher impact on mental and cognitive models in exceptional situations such as crisis. Such aspects are currently object of study [84,130]. | Mental model, cognitive model, mis-leading information, fake news |

| G5 | Dissonant mental models are often fostered by social networks at different levels (e.g. algorithms, influencers) which together undermine social cohesion and form barriers to shared situational awareness. To support effective crisis management there is a need to establish alignment of mental models and shared situational awareness, which is evidently a challenge [130,131]. | Dissonant mental model, influencer, shared situational awareness |

| G6 | In general terms, there is an intrinsic need to early detect and properly deal with rumors and fake news. It becomes more and more critical and relevant in crisis management [79,81,82]. | Rumours |

| G7 | There is a general lack of trust and effectiveness across mechanisms that strongly rely on social networks and the recent Covid-19 ‘infodemic’ is a clear example [130]. | Trust, Infodemic, Global Crisis |

| G8 | The COVID 19 pandemic has unfortunately provided a kind of stress-test for our system. Lessons and, more in general, the experience and knowledge we are developing from the global crisis has not yet been fully translated into tangible general frameworks [130]. | Knowledge Management, Global Crisis |

| G9 | Managing a global crisis (e.g. a pandemic) is a complex process that involves many stakeholders to be effective. Shared situation awareness through some mental models alignment may play a critical role [130]. | Global Crisis, Shared Situation Awareness |

| G10 | There is a relatively limited knowledge about the public-to-public interaction during the crisis and on the impact of this self-organizing system [21,76,132]. | Self-organizing system |

4.4. Research Questions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hiltz, S.R.; Van de Walle, B.; Turoff, M. The domain of emergency management information. In Information systems for emergency management; Routledge: 2014; pp. 15–32.

- Kreps, G.A. Sociological inquiry and disaster research. Annual review of sociology 1984, 10, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, K.; Larson, R.C. Disasters: lessons from the past 105 years. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2008, 17, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petak, W.J. Emergency management: A challenge for public administration. Public Administration Review 1985, 45, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettieri, E.; Masella, C.; Radaelli, G. Disaster management: findings from a systematic review. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, D. A framework for integrated emergency management. Public administration review 1985, 45, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, A.; Muraki, Y. Twitter for crisis communication: lessons learned from Japan’s tsunami disaster. International journal of web based communities 2011, 7, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudy, C.; Ruini, F.; Zanasi, A.; Przybyszewski, M.; Stachowicz, A. Using social media in crisis management: SOTERIA fusion center for managing information gaps. In Proceedings of the 2017 20th International Conference on Information Fusion (Fusion); 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Raue, S.; Johnson, C.W.; Storer, T. (SMA)2—a Social Media Audience Sharing Model for Authorities to support effective crisis communication. In Proceedings of the 7th IET International Conference on System Safety, incorporating the Cyber Security Conference 2012, 15-18 Oct. 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Rosson, M.B. How and Why People Twitter: The Role that Micro-blogging Plays in Informal Communication at Work; 2009.

- Fischer, D.; Posegga, O.; Fischbach, K. Communication Barriers in Crisis Management: a literature Review. In Proceedings of the ECIS; 2016; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi, M.; Ehnis, C.; Shahbazi, M.; Bunker, D. Tweeting from the shadows: Social media convergence behaviour during the 2017 Iran-Iraq earthquake. In Proceedings of the ISCRAM Asia Pacific; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A. Use of Social Media in Disaster Management; 2011; Volume 5.

- Fraustino, J.D.; Liu, B.; Jin, Y. Social media use during disasters: a review of the knowledge base and gaps. 2012.

- Stieglitz, S.; Mirbabaie, M.; Schwenner, L.; Marx, J.; Lehr, J.; Brünker, F. Sensemaking and communication roles in social media crisis communication. 2017.

- Mirbabaie, M.; Youn, S. Exploring sense-making activities in crisis situations. Proceedings of the 10th Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik (MKWI) 2018, 1656–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Procopio, C.H.; Procopio, S.T. Do you know what it means to miss New Orleans? Internet communication, geographic community, and social capital in crisis. Journal of applied communication research 2007, 35, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Castillo, C.; Diaz, F.; Vieweg, S. Processing social media messages in mass emergency: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2015, 47, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, D.; Ehnis, C.; Seltsikas, P.; Levine, L. Crisis management and social media: Assuring effective information governance for long term social sustainability. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST); 2013; pp. 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, C.; Heger, O.; Pipek, V. Combining real and virtual volunteers through social media. In Proceedings of the Iscram; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mirbabaie, M.; Ehnis, C.; Stieglitz, S.; Bunker, D.; Rose, T. Digital nudging in social media disaster communication. Information Systems Frontiers 2021, 23, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A.; Burgess, J. # qldfloods and@ QPSMedia: Crisis communication on Twitter in the 2011 south east Queensland floods. 2012.

- Plotnick, L.; Hiltz, S.R. Barriers to use of social media by emergency managers. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 2016, 13, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Designing for situation awareness: An approach to user-centered design; CRC press: 2016.

- Congress, U.S. “Homeland Security Act 2002” 107th Congress. Section 515 (6 U.S.C321d(b)(1)) 2002.

- Bower, G.H.; Morrow, D.G. Mental models in narrative comprehension. Science 1990, 247, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, D.; Gentner, D.; Stevens, A. Mental models. Human-computer Interaction, chap. Some Observations on Mental Models 1983, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. Mental models. Planning Review 1992, 20, 4–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G. The psychology of personal constructs: Volume two: Clinical diagnosis and psychotherapy; Routledge: 2003.

- Biggs, D.; Abel, N.; Knight, A.T.; Leitch, A.; Langston, A.; Ban, N.C. The implementation crisis in conservation planning: could “mental models” help? Conservation Letters 2011, 4, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance, R. A preliminary exploration of two approaches for documenting ‘mental models’ held by stakeholders in the Crocodile Catchment, South Africa. 2008.

- Reuter, C.; Schröter, J. Microblogging during the European floods 2013: What Twitter may contribute in German emergencies. International Journal of Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (IJISCRAM) 2015, 7, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.W.; Avery, E.J.; Park, S. The role of social media in local government crisis communications. Public Relations Review 2015, 41, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Security, H. Using Social Media for Enhanced Situation Awareness and Decision Support 2014.

- Veil, S.R.; Buehner, T.; Palenchar, M.J. A work-in-process literature review: Incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. Journal of contingencies and crisis management 2011, 19, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M. On-line strategic crisis communication: In search of a descriptive model approach. International Journal of Strategic Communication 2012, 6, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floreddu, P.B.; Cabiddu, F.; Evaristo, R. Inside your social media ring: How to optimize online corporate reputation. Business Horizons 2014, 57, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, B.F.; Austin, L.L. Examining the role of social media in effective crisis management: The effects of crisis origin, information form, and source on publics’ crisis responses. Communication research 2014, 41, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, E.-J.; Nekmat, E. Situational crisis communication and interactivity: Usage and effectiveness of Facebook for crisis management by Fortune 500 companies. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 35, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. 2007, 2.

- Cañas, A.J.; Hill, G.; Carff, R.; Suri, N.; Lott, J.; Gómez, G.; Eskridge, T.C.; Arroyo, M.; Carvajal, R. CmapTools: A knowledge modeling and sharing environment. 2004.

- Cañas, A.J.; Carff, R.; Hill, G.; Carvalho, M.; Arguedas, M.; Eskridge, T.C.; Lott, J.; Carvajal, R. Concept maps: Integrating knowledge and information visualization. Knowledge and information visualization: Searching for synergies 2005, 205-219.

- Novak, J.D.; Cañas, A.J. The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct them. Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition 2006, 1, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Son, J.; Aziz, Z.; Peña-Mora, F. Supporting disaster response and recovery through improved situation awareness. Structural survey 2008, 26, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieweg, S.; Hughes, A.L.; Starbird, K.; Palen, L. Microblogging during two natural hazards events: what twitter may contribute to situational awareness. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; 2010; pp. 1079–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Endsley, M.R. Situation Models: An Avenue to the Modeling of Mental Models. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting; 2000; Volume 44, pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, C.; Yahja, A.; Mostafavi, A. Disaster City Digital Twin: A vision for integrating artificial and human intelligence for disaster management. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 56, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation 2011, 55, 37–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, K.; Mohammad, K.; Ebadi, S. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development: Instructional Implications and Teachers’ Professional Development. English Language Teaching 2010, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L.F.; Kleiser, S.B.; Grau, S.L. Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Computers in Human Behavior 2015, 44, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Islam, M.N.; Whelan, E. What drives unverified information sharing and cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic? European journal of information systems 2020, 29, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, J.; Ehnis, C.; Clarke, R.J.; Bunker, D. Sydney siege, December 2014: A visualisation of a semantic social media sentiment analysis. 2018.

- Mirbabaie, M.; Ehnis, C.; Stieglitz, S.; Bunker, D. Communication roles in public events: A case study on Twitter communication. In Proceedings of the Information Systems and Global Assemblages.(Re) Configuring Actors, Artefacts, Organizations: IFIP WG 8.2 Working Conference on Information Systems and Organizations, IS&O 2014, Auckland, New Zealand, December 11-12, 2014; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnis, C.; Bunker, D. Social media in disaster response: Queensland police service-public engagement during the 2011 floods. 2012.

- Potter, E. Balancing conflicting operational and communications priorities: Social media use in an emergency management organization. In Proceedings of the ISCRAM 2016 Conference Proceedings-13th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management; 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Lazreg, M.; Chakraborty, N.R.; Stieglitz, S.; Potthoff, T.; Ross, B.; Majchrzak, T.A. Social media analysis in crisis situations: can social media be a reliable information source for emergency management services? 2018.

- Reuter, C.; Kaufhold, M.A. Fifteen years of social media in emergencies: a retrospective review and future directions for crisis informatics. Journal of contingencies and crisis management 2018, 26, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.; Potthoff, T.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Chakraborty, N.R.; Ben Lazreg, M.; Stieglitz, S. The diffusion of crisis-related communication on social media: an empirical analysis of Facebook reactions. 2018.

- Shemberger, M. Nonprofit organizations’ use of social media in crisis communication. In Social media and crisis communication; Routledge: 2017; pp. 227–237. [CrossRef]

- Redmiles, E.M.; Bodford, J.; Blackwell, L. “I just want to feel safe”: A Diary Study of Safety Perceptions on Social Media. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 2019; pp. 405–416.

- Nosouhi, M.R.; Sood, K.; Kumar, N.; Wevill, T.; Thapa, C. Bushfire Risk Detection Using Internet of Things: An Application Scenario. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 5266–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, K.K.T.; Corbitt, B.; Beekhuyzen, J. A knowledge management model to improve the development of bushfire communication products. Australasian Journal of Information Systems 2014, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongkusolkit, J.; Huang, Q. Situational awareness extraction: a comprehensive review of social media data classification during natural hazards. Annals of GIS 2020, 27, 5—28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrebnyakov, N.; Maldonado, E. Didn’t roger that: Social media message complexity and situational awareness of emergency responders. International Journal of Information Management 2018, 40, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, T.; Ratcliff, J.; O’Connor, M.; Oluic, S.; Rose, M.; Freeman, J.; Rainwater-Lovett, K. Technologies enabling situational awareness during disaster response: a systematic review. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2022, 16, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniz-Rodriguez, K.; Ofori, S.K.; Bayliss, L.C.; Schwind, J.S.; Diallo, K.; Liu, M.; Yin, J.; Chowell, G.; Fung, I.C.-H. Social media use in emergency response to natural disasters: a systematic review with a public health perspective. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2020, 14, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Vo, H. Examining the role of social media in California’s drought risk management in 2014. Natural Hazards 2015, 79, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, H.M.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Friedman, D.B.; Gentile, D.; Schrock, C.; Thomas, T.; West, D. Examining the role of Twitter in response and recovery during and after historic flooding in South Carolina. Journal of public health management and practice 2019, 25, E6–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.K.; Errett, N.A. Content, accessibility, and dissemination of disaster information via social media during the 2016 Louisiana floods. Journal of public health management and practice 2018, 24, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Oh, H.J. Normative mechanism of rumor dissemination on Twitter. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2017, 20, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T.W. Social networks and health: Models, methods, and applications; Oxford University Press: 2010.

- Liu, F.; Burton-Jones, A.; Xu, D. Rumors on social media in disasters: Extending transmission to retransmission. 2014.

- Albris, K. The switchboard mechanism: How social media connected citizens during the 2013 floods in Dresden. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 2018, 26, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.; Poblete, B.; Castillo, C. Twitter under crisis: Can we trust what we RT? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first workshop on social media analytics; 2010; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, E.; Vaca, C. Crisis management on Twitter: Detecting emerging leaders. In Proceedings of the 2017 Fourth International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG); 2017; pp. 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mirbabaie, M.; Bunker, D.; Stieglitz, S.; Marx, J.; Ehnis, C. Social media in times of crisis: Learning from Hurricane Harvey for the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic response. Journal of Information Technology 2020, 35, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofeditz, L.; Ehnis, C.; Bunker, D.; Brachten, F.; Stieglitz, S. Meaningful use of social bots? possible applications in crisis communication during Disasters; 2019.

- Stieglitz, S.; Meske, C.; Ross, B.; Mirbabaie, M. Going back in time to predict the future-the complex role of the data collection period in social media analytics. Information Systems Frontiers 2020, 22, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Kumari, M.; Sharma, T. Rumors detection, verification and controlling mechanisms in online social networks: A survey. Online Social Networks and Media 2019, 14, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of economic perspectives 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker, A.; Sliwa, A.; Dalvi, F.; Bontcheva, K. Rumour verification through recurring information and an inner-attention mechanism. Online Social Networks and Media 2019, 13, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrell, G.; Kochkina, E.; Liakata, M.; Aker, A.; Zubiaga, A.; Bontcheva, K.; Derczynski, L. SemEval-2019 Task 7: RumourEval 2019: Determining Rumour Veracity and Support for Rumours. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation: NAACL HLT 2019; 2019; pp. 845–854. [Google Scholar]

- Akhgar, B.; Fortune, D.; Hayes, R.E.; Guerra, B.; Manso, M. Social media in crisis events: Open networks and collaboration supporting disaster response and recovery. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International conference on technologies for Homeland Security (HST); 2013; pp. 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L.; Keller, T.; Neely, S.; DePaula, N.; Robert-Cooperman, C. Crisis communications in the age of social media: A network analysis of Zika-related tweets. Social science computer review 2018, 36, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, O.; Agrawal, M.; Rao, H.R. Community intelligence and social media services: A rumor theoretic analysis of tweets during social crises. MIS quarterly 2013, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntire, D.A. Coordinating multi-organisational responses to disaster: lessons from the March 28, 2000, Fort Worth tornado. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2002, 11, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, B.S.; Baker, A.H. Communication challenges in emergency response. Communications of the ACM 2007, 50, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Cho, S.; Sankaran, S.; Sovereign, M. A framework for designing a global information network for multinational humanitarian assistance/disaster relief. Information Systems Frontiers 2000, 1, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haataja, M.; Laajalahti, A.; Hyvärinen, J. Expert views on current and future use of social media among crisis and emergency management organizations: Incentives and barriers. Human Technology 2016, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surowiecki, J. The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies, and nations; Doubleday & Co: New York, NY, US, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, T.B.; Ferrell, W.R. Man-machine systems; Information, control, and decision models of human performance; the MIT press: 1974.

- Verma, S.; Vieweg, S.; Corvey, W.; Palen, L.; Martin, J.; Palmer, M.; Schram, A.; Anderson, K. Natural language processing to the rescue? extracting” situational awareness” tweets during mass emergency. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media; 2011; pp. 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velev, D.; Zlateva, P. An analysis of the relation between natural disasters and Big Data. International Journal of Data Science 2016, 1, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofeditz, L.; Ehnis, C.; Bunker, D.; Brachten, F.; Stieglitz, S. Meaningful Use of Social Bots? Possible Applications in Crisis Communication during Disasters. In Proceedings of the ECIS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chermack, T.J.; Song, J.H.; Nimon, K.; Choi, M.; Korte, R.F. The development and assessment of an instrument for measuring mental model styles in Korea. Learning and Performance Quarterly 2012, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, D.N.; Sterman, J.D. Expert knowledge elicitation to improve formal and mental models. System Dynamics Review: The Journal of the System Dynamics Society 1998, 14, 309–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, M.; Warren, M.; Carr, R. Understanding the use of social media by organisations for crisis communication. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 63, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M. Cognitive styles and the effects of stress from cognitive load and time pressures on judgemental decision making with learning simulations: Implications for HRD. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management 2016, 16, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppänen, H.; Mäkelä, J.; Luokkala, P.; Virrantaus, K. Developing shared situational awareness for emergency management. Safety science 2013, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palen, L.; Liu, S.B. Citizen communications in crisis: anticipating a future of ICT-supported public participation. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 2007; pp. 727–736.

- Hughes, A.L.; Palen, L. The evolving role of the public information officer: An examination of social media in emergency management. Journal of homeland security and emergency management 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, R.M.; Elmer, S.; Lurie, N. Integrating social media into emergency-preparedness efforts. New England journal of medicine 2011, 365, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, I.C.-H.; Tse, Z.T.H.; Cheung, C.-N.; Miu, A.S.; Fu, K.-W. Ebola and the social media. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Nalluru, G.; Pandey, R.; Purohit, H. Relevancy classification of multimodal social media streams for emergency services. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP); 2019; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, C.; Spielhofer, T. Towards social resilience: A quantitative and qualitative survey on citizens’ perception of social media in emergencies in Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2017, 121, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.C.; Wilson, B.G. The dynamic role of social media during Hurricane# Sandy: An introduction of the STREMII model to weather the storm of the crisis lifecycle. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 54, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskin, E.H., P. Hurricane Sandy and Twitter. 2012.

- Chatfield, A.T.; Scholl, H.J.; Brajawidagda, U. # Sandy tweets: citizens’ co-production of time-critical information during an unfolding catastrophe. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2014; pp. 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim, Y.; Yang, L.; Pan, S.L.; Kaewkitipong, L.; Ractham, P. The emergence of social media as boundary objects in crisis response: a collective action perspective. 2013.

- Kaewkitipong, L.; Chen, C.; Ractham, P. Lessons learned from the use of social media in combating a crisis: A case study of 2011 Thailand flooding disaster. 2012.

- Koob, P. Australian emergency management glossary; manual 3. Commonwealth of Australia. First Published 1998.

- Conrado, S.P.; Neville, K.; Woodworth, S.; O’Riordan, S. Managing social media uncertainty to support the decision making process during emergencies. Journal of Decision Systems 2016, 25, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Santen, W.; Jonker, C.; Wijngaards, N. Crisis decision making through a shared integrative negotiation mental model. International Journal of Emergency Management 2009, 6, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management communication quarterly 2002, 16, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, L.; Theunissen, P. Reputations at risk: Engagement during social media crises. Public Relations Review 2015, 41, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Bowman, T.D.; Holmberg, K.; Tsou, A.; Sugimoto, C.R.; Larivière, V. Tweets as impact indicators: Examining the implications of automated “bot” accounts on T witter. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2016, 67, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachten, F.; Stieglitz, S.; Hofeditz, L.; Kloppenborg, K.; Reimann, A.-L.F. Strategies and Influence of Social Bots in a 2017 German state election—A case study on Twitter. In Proceedings of the ACIS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brachten, F.; Mirbabaie, M.; Stieglitz, S.; Berger, O.; Bludau, S.; Schrickel, K. Threat or Opportunity?—Examining Social Bots in Social Media Crisis Communication. In Proceedings of the ACIS; 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi, A.; Shirazi, F.; Hajli, N.; Tajvidi, M. Using artificial intelligence to detect crisis related to events: Decision making in B2B by artificial intelligence. Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 91, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, J.A.; Zehe, E.; Redick, C.; Bah, A.; Cowger, K.; Camara, M.; Diallo, A.; Gigo, A.N.I.; Dhillon, R.S.; Liu, A. Introduction of mobile health tools to support Ebola surveillance and contact tracing in Guinea. Global Health: Science and Practice 2015, 3, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, U.A.; Sidi, F.; Jabar, M.A.; Nor, R.N.H.; Abdullah, S.; Ishak, I.; Alabadla, M.; Alkhalifah, A. How Advanced Technological Approaches Are Reshaping Sustainable Social Media Crisis Management and Communication: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.L.; Nichols, E.; McKechnie, M.; McCarthy, S. Combining crisis management and evidence-based management: The Queensland floods as a teachable moment. Journal of Management Education 2013, 37, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagar, C. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. asis&t 2010.

- Planella Conrado, S.; Neville, K.; Woodworth, S.; O’Riordan, S. Managing social media uncertainty to support the decision making process during Emergencies. Journal of Decision System 2016, 25, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kelly, G.; Janssen, M.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Clement, M. Social media: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Information Systems Frontiers 2018, 20, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, T.; Pramanik, P.; Bhattacharya, I.; Boral, N.; Ghosh, S. Analysis and early detection of rumors in a post disaster scenario. Information Systems Frontiers 2018, 20, 961–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Castillo, C.; Lucas, J.; Meier, P.; Vieweg, S. AIDR: Artificial intelligence for disaster response. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on world wide web, 2014; pp. 159–162.

- WHO. Infodemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic#tab=tab_1.

- Chu, S.K. COVID-19 Infodemic: Empowering Australia against infodemic. 2021.

- Bunker, D. Who do you trust? The digital destruction of shared situational awareness and the COVID-19 infodemic. International Journal of Information Management 2020, 55, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzing, M. “Strongly recommended” revisiting decisional privacy to judge hypernudging in self-tracking technologies. Philosophy & Technology 2019, 32, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, D.; Sleigh, T.; Levine, L.; Ehnis, C. Disaster Management: Building Resilient Systems to Aid Recovery. In Proceedings of the Research proceedings from the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC & AFAC conference; 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pileggi, S.F. Walking Together Indicator (WTI): Understanding and Measuring World Inequality. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).