Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

06 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting And Study Design

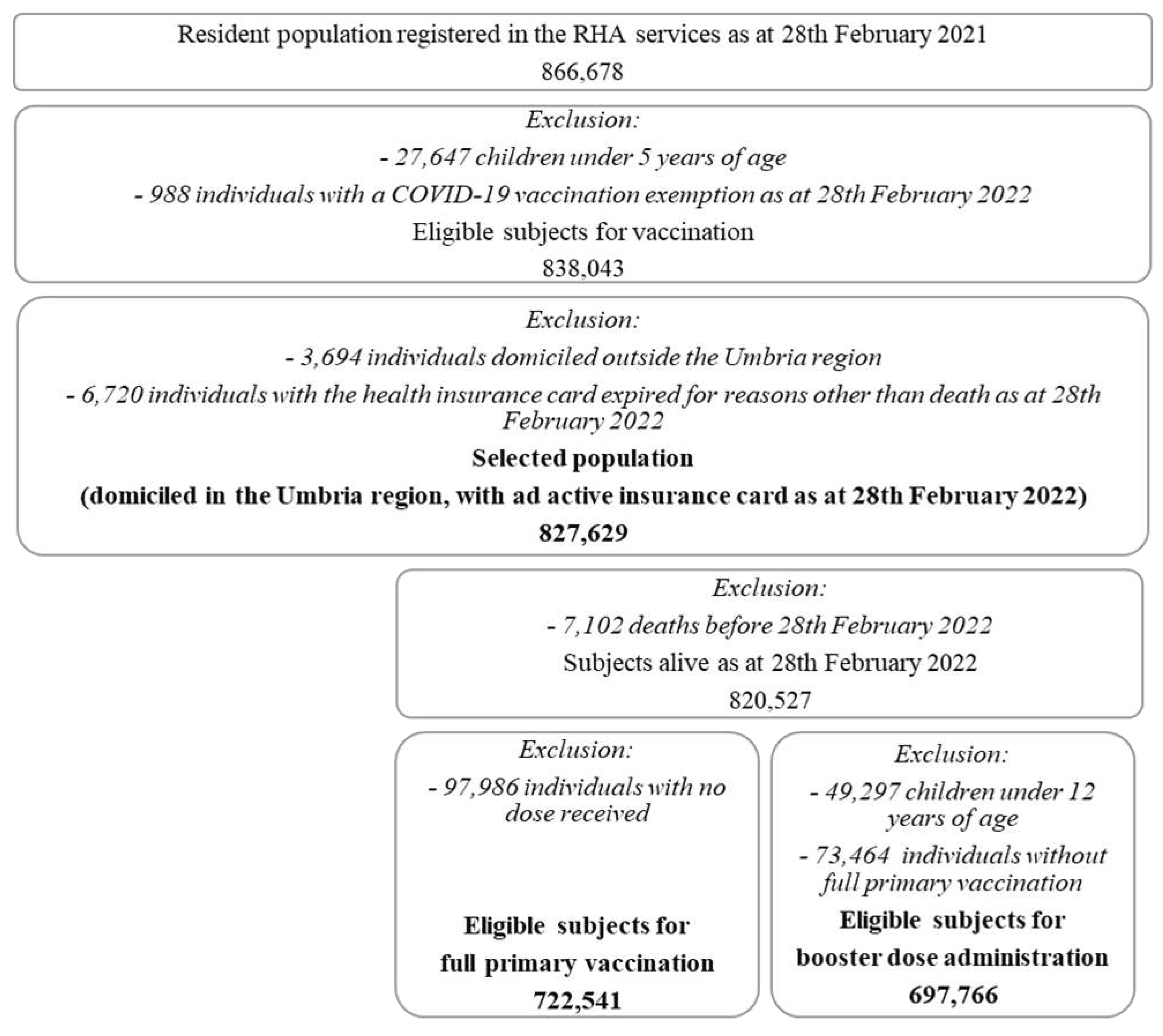

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Study Endpoints And Variables

- -

- sex (male or female),

- -

- age (5-11, 12-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, 80-89, 90+),

- -

- citizenship (Italian or non-Italian),

- -

- holding of an officially recognized exemption due to a chronic/rare pathology or a disability, used as a proxy for frailty (present or absent),

- -

- holding of a General Practitioner (GP) or a Family Pediatrician (FP) that is commonly chosen by each resident to get most of the primary care (present or absent);

- -

- the Italian National Deprivation Index at the Umbria regional level, a composite indicator associated to the municipality of residence and categorized in quintiles - from most (group 5) to least (group 1) deprived - weighted by the regional 2011 census population, according to Rosano 2020 [30].

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitehead, M. The Concepts and Principles of Equity and Health. Int. J. Heal. Serv. 1992, 22, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J. COVID-19: exposing and amplifying inequalities. J. Epidemiology Community Heal. 2020, 74, 681–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.M.; Friedrichs, M.; Wagstaff, S.; Sage, K.; LaCross, N.; Bui, D.; McCaffrey, K.; Barbeau, B.; George, A.; Rose, C.; et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Incidence, Hospitalizations, and Testing, by Area-Level Deprivation — Utah, March 3–July 9, 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, N.M.; Friedrichs, M.; Wagstaff, S.; Sage, K.; LaCross, N.; Bui, D.; McCaffrey, K.; Barbeau, B.; George, A.; Rose, C.; et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Incidence, Hospitalizations, and Testing, by Area-Level Deprivation — Utah, March 3–July 9, 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheiham, A. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. A report of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) 2008. Community Dent Heal. 2009, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Bell, R.; Bloomer, E.; Goldblatt, P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, A.; Ventura, M.; Spadea, T.; Rossi, P.G.; Bartolini, L.; Battisti, L.; Cacciani, L.; Caranci, N.; Cernigliaro, A.; De Giorgi, M.; et al. Barriers to Accessing Primary Care and Appropriateness of Healthcare Among Immigrants in Italy. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 817696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavarini, M.; Lanari, D.; Minelli, L.; Pieroni, L.; Salmasi, L. Immigrant mothers and access to prenatal care: evidence from a regional population study in Italy. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e008802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncello, C.; Ferro, A.; Fonzo, M.; Zanovello, S.; Napoletano, G.; Russo, F.; Baldo, V.; Cocchio, S. Socioeconomic Determinants in Vaccine Hesitancy and Vaccine Refusal in Italy. Vaccines 2020, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleringer, S.; Abdelwahab, J.; Vandenent, M. Polio Supplementary Immunization Activities and Equity in Access to Vaccination: Evidence From the Demographic and Health Surveys. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, S531–S539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.A.; Hartner, A.-M.; Echeverria-Londono, S.; Roth, J.; Li, X.; Abbas, K.; Portnoy, A.; Vynnycky, E.; Woodruff, K.; Ferguson, N.M.; et al. Vaccine equity in low and middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2022, 21, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Venegas, M.; Cano-Ibáñez, N.; Khan, K. Vaccination coverage among migrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. de Fam. SEMERGEN 2022, 48, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J.C.; Calo, W.A.; Brewer, N.T. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2019, 123, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; van Hoek, A.; Boccia, D.; Thomas, S.L. Lower vaccine uptake amongst older individuals living alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis of social determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2315–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, C.S.; Mujeeb, A.A.; Mirza, M.S.; Chaudhry, B.; Khan, S.J. Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Systematic Review of Associated Social and Behavioral Factors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, T.; Moghtaderi, A.; Lueck, J.A.; Hotez, P.; Strych, U.; Dor, A.; Fowler, E.F.; Motta, M. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113638–113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Schneider, S.; Margraf, J. To vaccinate or not to vaccinate!? Predictors of willingness to receive Covid-19 vaccination in Europe, the U.S., and China. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0260230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.S.; Abdullah, R.; Vered, S.; Nitzan, D. A study of ethnic, gender and educational differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Israel – implications for vaccination implementation policies. Isr. J. Heal. Policy Res. 2021, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primieri, C.; Bietta, C.; Giacchetta, I.; Chiavarini, M.; de Waure, C. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance or hesitancy in Italy: an overview of the current evidence. . 2023, 59, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, V.; Lorini, C.; Stacchini, L.; Stancanelli, E.; Guida, A.; Radi, A.; Morittu, C.; Zimmitti, S.; Alderotti, G.; Del Riccio, M.; et al. Determinants of Actual COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in a Cohort of Essential Workers: An Area-Based Longitudinal Study in the Province of Prato, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, I.; Mandalari, M.; Cesari, E.; Borriello, C.R.; Ercolanoni, M.; Preziosi, G. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Uptake during Pregnancy in Regione Lombardia, Italy: A Population-Based Study of 122,942 Pregnant Women. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesaroni, G.; Calandrini, E.; Balducci, M.; Cappai, G.; Di Martino, M.; Sorge, C.; Nicastri, E.; Agabiti, N.; Davoli, M. Educational Inequalities in COVID-19 Vaccination: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Adult Population in the Lazio Region, Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.G.; Tunesi, S.; Consolazio, D.; Decarli, A.; Bergamaschi, W. Evaluation of the anti-COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the Metropolitan Area of Milan (Lombardy Region, Northern Italy). Valutazione della campagna vaccinale anti-COVID-19 nella ATS di Milano. Epidemiol. Prev. 2021, 45, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noia, V.; Renna, D.; Barberi, V.; Di Civita, M.; Riva, F.; Costantini, G.; Aquila, E.D.; Russillo, M.; Bracco, D.; La Malfa, A.M.; et al. The first report on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine refusal by patients with solid cancer in Italy: Early data from a single-institute survey. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 153, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, G.; Pelullo, C.P.; Lanzano, R.; Lombardi, C.; Nese, G.; Pavia, M. COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake and Related Determinants in Detained Subjects in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, F.; Malvaso, A.; Chiesi, F.; Laganà, V.; Servidio, R.; Isella, V.; Ferrarese, C.; Gottardi, F.; Stella, E.; Agosta, F.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among family caregivers of people with dementia: The role of attitudes toward vaccination, perceived social support and personality traits. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 923316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROPORTION of PLWH NOT VACCINATED for COVID-19 in ITALY and PREDICTORS. Tavelli, A.; Cicalini, S.; Barbanotti, D.; Antinori, S.; Segala, D.; Guaraldi, G.; Guastavigna, M.; Lazzaretti, C.; Puoti, M.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F.; Castagna, A.; Girardi, E.; Monforte, A. D.; Antinori, A.. Topics in Antiviral Medicine ; 30(1 SUPPL):348, 2022. EMBASE |ID: covidwho-1880938. Tavelli, A.

- Umbria in Cifre. Available online: https://webstat.regione.umbria.it/popres_010122/#:~:text=Al%201%20gennaio%202022%20risultano,218.330%20in%20provincia%20di%20Terni.

- Decreto del Ministero della Salute 12 marzo 2021 (GU Serie Generale n.72 del 24-03-2021).

- Rosano A, Pacelli B, Zengarini N, Costa G, Cislaghi C, Caranci N. Aggiornamento e revisione dell’indice di deprivazione italiano 2011 a livello di sezione di censimento. EpidemiolPrev. 2020. Available online: https://epiprev.it/4849.

- Report Vaccini Anti COVID-19. Available online: https://www.governo.it/it/cscovid19/report-vaccini.

- Ferrara, M.; Bertozzi, G.; Volonnino, G.; Di Fazio, A.; Di Fazio, N.; Arcangeli, M.; La Russa, R.; Frati, P. Learning from the Past to Improve the Future—Vaccine Hesitancy Determinants in the Italian Population: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, E.; Cartledge, S.; Damery, S.; Greenfield, S. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic; a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafadar, A.H.; Tekeli, G.G.; Jones, K.A.; Stephan, B.; Dening, T. Determinants for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the general population: a systematic review of reviews. J. Public Heal. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European House Ambrosetti, Gli italiani e le vaccinazioni nello scenario post-covid-19, fiducia o scetticismo? Centro Interdipartimentale per l’Etica e l’Integrità della Ricerca. Available online: https://eventi.ambrosetti.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/221/2021/11/20220614-Paper-Vaccine-Confidence.pdf.

- Vukovic, V.; Lillini, R.; Lupi, S.; Fortunato, F.; Cicconi, M.; Matteo, G.; Arata, L.; Amicizia, D.; Boccalini, S.; Bechini, A.; et al. Identifying people at risk for influenza with low vaccine uptake based on deprivation status: a systematic review. Eur. J. Public Heal. 2020, 30, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayorinde, A.; Ghosh, I.; Ali, I.; Zahair, I.; Olarewaju, O.; Singh, M.; Meehan, E.; Anjorin, S.S.; Rotheram, S.; Barr, B.; et al. Health inequalities in infectious diseases: a systematic overview of reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucyibaruta, G.; Blangiardo, M.; Konstantinoudis, G. Community-level characteristics of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in England: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2022, 37, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendolia, S.; Walker, I. COVID-19 vaccination intentions and subsequent uptake: An analysis of the role of marginalisation in society using British longitudinal data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 321, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiden, A.L.; Barratt, J.; Nyaku, M.K. Drivers of and barriers to routine adult vaccination: A systematic literature review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2127290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, I.; Mandalari, M.; Cesari, E.; Borriello, C.R.; Ercolanoni, M.; Preziosi, G. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Uptake during Pregnancy in Regione Lombardia, Italy: A Population-Based Study of 122,942 Pregnant Women. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Vaccinable | Not adherent to vaccination campaign (any dose) (N=827,629) |

Failed to complete the full primary vaccination (N=722,541) |

Failed to get the booster dose (N=697,766) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | % | % | % | |

| Total | 827,629 | 100.0 | 11.8 | 1.2 | 21.5 |

| Sex | |||||

| Males | 397,820 | 48.1 | 11.7 | 1.21 | 22.3 |

| Females | 429,809 | 51.9 | 12.0 | 1.18 | 20.8 |

| Age | |||||

| Average (SD) | 49.3 (22.9) | 33.7 (24.2) | 32.7 (24.2) | 40.0 (19.4) | |

| 5-11 | 49,297 | 6.0 | 62.3 | 13.4 | - |

| 12-19 | 62,983 | 7.6 | 14.0 | 2.3 | 51.8 |

| 20-29 | 77,340 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 1.3 | 37.1 |

| 30-39 | 89,244 | 10.8 | 11.9 | 1.0 | 31.3 |

| 40-49 | 119,335 | 14.4 | 10.6 | 0.7 | 24.6 |

| 50-59 | 135,107 | 16.3 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 18.2 |

| 60-69 | 113,374 | 13.7 | 7.0 | 0.6 | 11.0 |

| 70-79 | 96,886 | 11.7 | 4.7 | 0.4 | 8.3 |

| 80-89 | 65,991 | 8.0 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 6.6 |

| 90+ | 18,072 | 2.2 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 9.2 |

| Citizenship | |||||

| Italian | 747,528 | 90.3 | 10.3 | 1.1 | 19.8 |

| Non-Italian | 80,101 | 9.7 | 26.1 | 2.8 | 41.4 |

| Comorbidity/Disability* | |||||

| Yes | 242,108 | 29.3 | 5.7 | 0.6 | 12.5 |

| No | 585,521 | 70.7 | 14.4 | 1.5 | 25.8 |

| GP/FP | |||||

| Yes | 818,101 | 98.8 | 11.4 | 1.2 | 21.4 |

| No | 9,528 | 1.2 | 47.0 | 4.3 | 30.6 |

| Deprivation | |||||

| 1 quintile | 167,221 | 20.2 | 12.1 | 1.3 | 21.2 |

| 2 quintile | 160,686 | 19.4 | 11.4 | 1.1 | 20.5 |

| 3 quintile | 185,307 | 22.4 | 12.1 | 1.2 | 22.0 |

| 4 quintile | 155,285 | 18.8 | 10.9 | 1.1 | 21.2 |

| 5 quintile | 159,130 | 19.2 | 12.7 | 1.2 | 22.6 |

| Not adherent to the vaccine campaign (any dose) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=827,629) | Males (N=397,820) | Females (N=429,809) | ||||

| Characteristics | fully-adj. OR | 95% C.I. | fully-adj. OR | 95% C.I. | fully-adj. OR | 95% C.I. |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | (Reference) | |||||

| Females | 1.042 | 1.030-1.054 | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| 5-11 | 29.571 | 27.015-32.369 | 39.681 | 35.990-43.752 | 24.910 | 22.542-27.527 |

| 12-19 | 2.740 | 2.534-2.962 | 3.757 | 3.420-4.127 | 2.258 | 2.079-2.453 |

| 20-29 | 1.689 | 1.573-1.814 | 2.279 | 2.109-2.463 | 1.416 | 1.294-1.549 |

| 30-39 | 2.034 | 1.926-2.148 | 2.794 | 2.593-3.010 | 1.670 | 1.575-1.771 |

| 40-49 | 1.916 | 1.801-2.038 | 2.736 | 2.527-2.963 | 1.513 | 1.407-1.626 |

| 50-59 | 1.655 | 1.569-1.745 | 2.216 | 2.057-2.388 | 1.390 | 1.310-1.475 |

| 60-69 | 1.510 | 1.436-1.589 | 1.872 | 1.749-2.002 | 1.353 | 1.274-1.437 |

| 70-79 | 1.096 | 1.038-1.158 | 1.247 | 1.156-1.345 | 1.045 | 0.977-1.118 |

| 80-89 | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | |||

| 90+ | 1.662 | 1.543-1.790 | 1.588 | 1.375-1.834 | 1.585 | 1.465-1.714 |

| Citizenship | ||||||

| Italian | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | |||

| Non-Italian | 2.878 | 2.678-3.093 | 2.642 | 2.478-2.816 | 3.092 | 2.839-3.368 |

| Comorbidity/Disability* | ||||||

| Yes | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||||

| No | 1.432 | 1.378-1.490 | 1.457 | 1.396-1.520 | 1.406 | 1.349-1.465 |

| GP/FP | ||||||

| Yes | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||||

| No | 8.919 | 7.731-10.289 | 8.565 | 7.324-10.017 | 9.391 | 8.036-10.975 |

| Deprivation | ||||||

| 1 quintile | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | |||

| 2 quintile | 0.902 | 0.773-1.053 | 0.913 | 0.780-1.067 | 0.893 | 0.764-1.043 |

| 3 quintile | 0.938 | 0.816-1.079 | 0.941 | 0.819-1081 | 0.935 | 0.810-1.079 |

| 4 quintile | 0.791 | 0.719-0.870 | 0.799 | 0.732-0.873 | 0.781 | 0.704-0.867 |

| 5 quintile | 1.021 | 0.873-1.194 | 1.034 | 0.880-2.215 | 1.009 | 0.865-1.177 |

| Failure to complete the primary vaccination cycle (N=722,541) |

Failure to get the booster dose (N=697,766) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | fully-adj. OR | 95% C.I | fully-adj. OR | 95% C.I |

| Sex | ||||

| Males | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| Females | 1.030 | 0.987-1.075 | 0.968 | 0.957-0.980 |

| Age | ||||

| 5-11 | 29.414 | 25.239-34.279 | - | - |

| 12-19 | 4.123 | 3.563-4.772 | 12.769 | 12.175-13.392 |

| 20-29 | 2.238 | 1.941-2.581 | 6.883 | 6.367-7.441 |

| 30-39 | 1.597 | 1.334-1.912 | 5.160 | 4.859-5.479 |

| 40-49 | 1.225 | 1.028-1.460 | 3.805 | 3.621-3.998 |

| 50-59 | 1.595 | 1.351-1.882 | 2.733 | 2.600-2.873 |

| 60-69 | 1.145 | 0.964-1.360 | 1.618 | 1.547-1.694 |

| 70-79 | 0.931 | 0.788-1.101 | 1.248 | 1.196-1.302 |

| 80-89 | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| 90+ | 1.834 | 1.469-2.290 | 1.474 | 1.384-1.569 |

| Citizenship | ||||

| Italian | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| Non Italian | 2.732 | 2.588-2.884 | 2.201 | 2.039-2.375 |

| Comorbidity/Disability* | ||||

| Yes | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| No | 1.139 | 1.071-1.211 | 1.227 | 1.208-1.246 |

| GP/FP | ||||

| Yes | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| No | 4.771 | 3.968-5.738 | 1.487 | 1.352-1.635 |

| Deprivation | ||||

| 1 quintile | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| 2 quintile | 0.840 | 0.747-0.943 | 0.943 | 0.873-1.018 |

| 3 quintile | 0.933 | 0.841-1.035 | 1.016 | 0.940-1.098 |

| 4 quintile | 0.758 | 0.696-0.825 | 0.916 | 0.873-0.961 |

| 5 quintile | 0.912 | 0.825-1.007 | 1.052 | 0.994-1.114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).