Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

06 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The sustainable development goals report. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Menperin: Kontribusi industri batik signifikan bagi perekonomian nasional (Industry Minister: Batik industry contribution is significant to national economy). Available online: https://www.alinea.id/bisnis/menperin-kontribusi-industri-batik-signifikan-bagi-perekonomian-nasional-b2cBY97i0 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- EKONID. Clean Batik Initiative: Second year achievement report. EKONID, Indonesia, 2012.

- Budiono, G.; Vincent, A. Batik Industry of Indonesia: The Rise, Fall and Prospects. Studies in Business & Economics. 2010, 5, 156–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kemenperin dorong pertumbuhan start-up kerajinan dan batik (The Ministry of Industry encourages the growth of handicraft and batik start-ups). Available online: https://investor.id/business/kemenperin-dorong-pertumbuhan-startup-kerajinan-dan-batik (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- EKONID. Clean batik initiative: Third year achievement report. EKONID, Indonesia, 2013.

- Handayani, W.; Kristijanto, A. I.; Hunga, A. I. R. Behind the eco-friendliness of “batik warna alam”: Discovering the motives behind the production of batik in Jarum village, Klaten. Wacana. 2018, 19, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apriyani, N. Industri batik: Kandungan limbah cair dan metode pengolahannya (Batik industry: Liquid waste content and processing methods). Media Ilmiah Teknik Linkungan (MITL). 2018, 3, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romadhon, Y. Kebijakan pengelolaan air limbah dalam penanganan limbah batik di Kota Pekalongan (Wastewater management policy in handling batik waste in Pekalongan City). Journal of International Relations. 2017, 4, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- The Minister of Industry, Decree No. 39 Year 2019 concerning Green Industry Standards (GIS) for batik industry. Available online: http://jdih.kemenperin.go.id/site/template3/2575 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Pastakia, A. Grassroots ecopreneurs: Change agents for a sustainable society. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 1998, 11, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaper, M. The essence of ecopreneurship. Greener Management International. 2002, 38, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuyler, G. Merging Economic and Environmental Concerns through Ecopreneurship. Digest. 1998, 8, 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Indrayani, L. Upaya strategis pengelolaan limbah industri batik dalam mewujudkan batik ramah lingkungan (Strategic efforts of batik industry waste management in realizing environmentally friendly batik). Proceedings of Seminar Nasional Industri Kerajinan Dan Batik 2019, Jogjakarta, Indonesia, 8 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Félonneau, M.L.; Becker, M. Pro-environmental attitudes and behavior: Revealing perceived social desirability. Revue internationale de psychologie sociale. 2008, 21, 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Revell, A.; Stokes, D.; Chen, H. Small businesses and the environment: turning over a new leaf? Business Strategy and the Environment. 2010, 19, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Sussman, R. Environmental attitudes. In The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology; Clayton, S.D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, J.; Walton, S. What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. 2010, 16, 204–228. [Google Scholar]

- Linnanen, L. An Insider’s Experiences with Environmental Entrepreneurship. Greener Management International. 2002, 2002, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastakia, A. Assessing ecopreneurship in the context of a developing country: the case of India. Greener Management International. 2002, 38, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Bouman, N.; Vijfvinkel, S. Environmental sustainability and financial performance of SMEs. EIM Business and Policy Research. 2011, Scales Research Reports H201101.

- Williams, S.; Schaefer, A. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Sustainability: Managers’ Values and Engagement with Environmental and Climate Change Issues. Business Strategy and the Environment. 2013, 22, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A. A.; Essers, C.; van Riel, A. C. R. The adoption of ecopreneurship practices in Indonesian craft SMEs: value-based motivations and intersections of identities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. 2021, 27, 730–752. [Google Scholar]

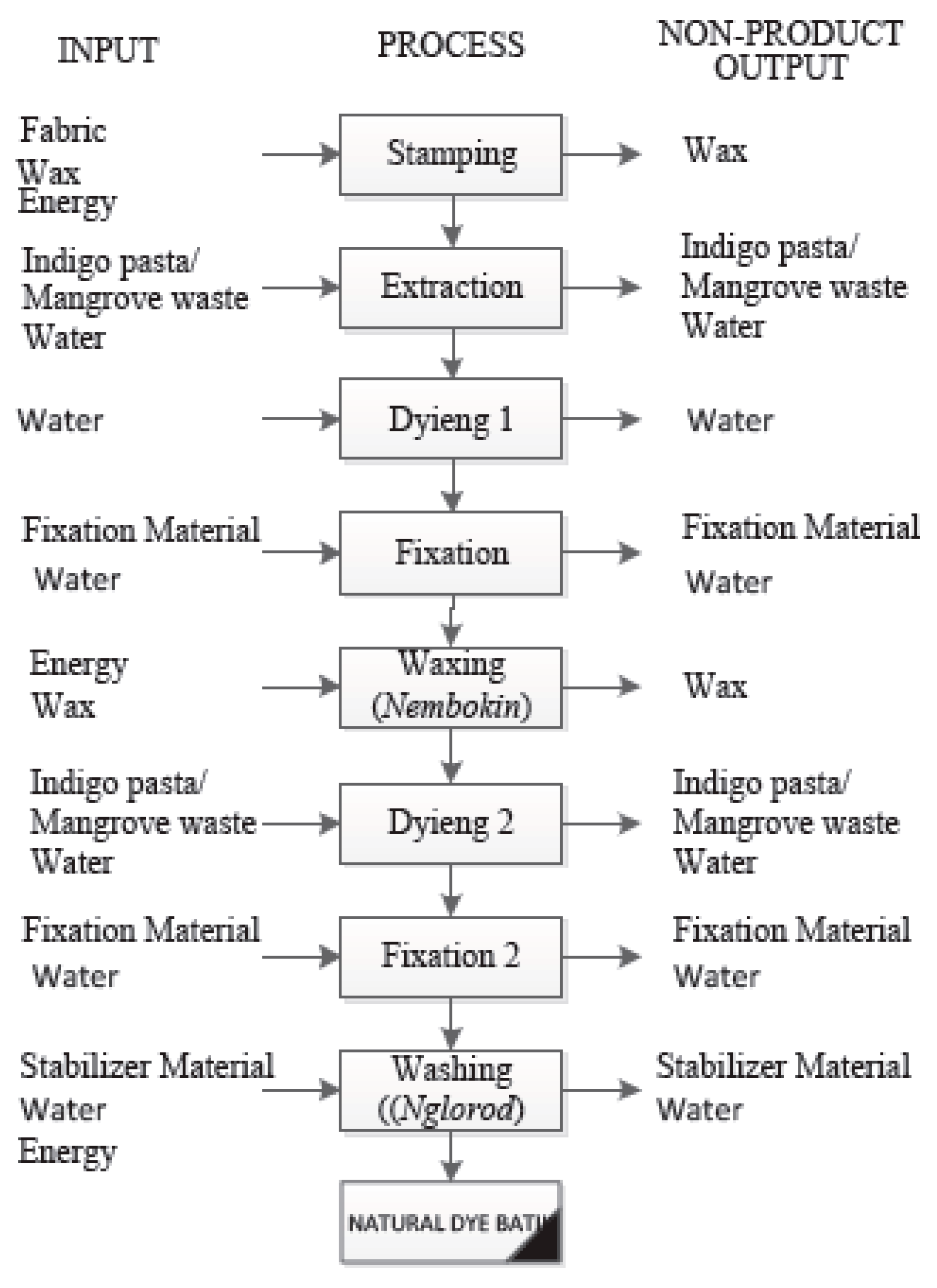

- Hartini, S.; Manurung, J.; Rumita, R. Sustainable-value stream mapping to improve manufacturing sustainability performance: Case study in a natural dye batik SME’s. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2021, 1072, 12066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V. K.; Sangwan, K. S. Modeling drivers for successful adoption of environmentally conscious manufacturing. Journal of Modelling in Management. 2014, 9, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Industry of Republic of Indonesia: Green Industry Concept and Implementation. Available online: https://kemenperin.go.id/download/6297/Efisiensi-dan-Efektivitas-dalam-Implementasi-Industri-Hijau (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Booth, A.; Sutton, A.; Papaioannou, D. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2016.

- Indarti, I. A. T.R.; Peng, L. H. 2020. Sustainable Batik Production: Review and Research Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research and Academic Community Services (ICRACOS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 7 September 2019. Surabaya, Indonesia, 7 September 2019.

- Empower researchers to take on today’s global challenges. Available online: https://about.proquest.com/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Karsam, K.; Widiana, M. E.; Widyastuty, A. A. S. A.; & Hidayati, K.; & Hidayati, K. Preservation, Standardization and Information Technology 4.0 of Traditional Gedog Tuban Batik to be Competitive in Marketing During Covid-19. Theoretical and Practical Research in the Economic Fields. 2022, 13, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiroen, V. J. Creating Batik Lasem through a comparative study of Batik Lasem and Champa in the 15th to 19th century”. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2021, 729, 12064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, E. D.; Susilowati, I. Sustainable Competitive Advantage of SMEs through Resource and Institutional-Based Management: An Empirical Study of Batik SMEs in Central Java, Indonesia. Tržište/Market. 2019, 31, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunikawati, N. A.; Istiqomah, N.; Jabbar, M. A.; Sidi, F. Model of Development Rural Tourism Batik in Banyuwangi: A sustainable Development Approach. E3S Web of Conferences, 2020, 208, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, A.; Pandanwangi, A. Eco-friendly batik painting wax made from tamarind seed powder (Tamarindus indica L). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, W.; Widianarko, B.; Pratiwi, A. R. The water use for batik production by batik SMEs in Jarum Village, Klaten Regency, Indonesia: What are the key factors? IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, S. R.; Affanti, T. B.; Josef, A. I.; Nurcahyanti, D. Batik stamp canting made of wastepaper material as a frugal innovation in batik. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 905, 12125. [Google Scholar]

- Lias, H.; Ismail, A. R.; Abd Hamid, H. Malaysia textile craft industry: Innovation inspired by bamboo for batik block contemporary design. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2020, 549, 12087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartono, F. A.; Fitriani, F. Batik Grajen: Eco-friendly batik utilizing wood waste for batik dye. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2021, 905, 12146. [Google Scholar]

- Failisnur, F.; Sofyan, S.; Silfia, S. Colorimetric properties of batik fabrics colored using gambier liquid waste. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2021, 1940, 12092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, N. S. M.; Ismail, A. R.; Hasbullah, S. W.; Kadir, N. A. A review on sustainable development and heritage preservation and its conceal detrimental in batik dyeing. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 549, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, N. S. M.; Ismail, A. R.; Kadir, N. A.; Hasbullah, S. W.; Hassan, H.; Jusoh, N. Resurgence the Local Knowledge: Environmental Catalysis Practiced in Local Textile Dyeing. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 12043–616. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumawati, N.; Muslim, S. Exploration and Standarization of Coconut Fiber Waste Utilization in Batik Dyeing Process. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 709, 12034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataram, S. Natural batik dyes from Terminalia bellirica, Ceriop condolleana, Cudrania javanensis and Pelthopherum pterocarpum. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 905, 12019. [Google Scholar]

- Nurcahyanti, D.; Wahyuningsih, N.; Amboro, J. L. Natural clay dye to develop eco-friendly products based on regional potential in Batik Crafts Center of Jarum Village, Bayat Subdistrict, Klaten Regency. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 905, 12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saefudin. (2020). Prospects of biomass wood wastes as natural dye stuffs for batik clothes and other woven fabrics. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 415, 12020. [Google Scholar]

- Arifan, F.; Nugraheni, F. S.; Devara, H. R.; Lianandya, N. E. Wastewater treatment from batik industries using TiO2 nanoparticles. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2018, 116, 12046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiyanto, S.; Purnaweni, H.; Sunoko, H. R. Environmental analysis of the impacts of batik waste water polution on the quality of dug well water in the batik industrial center of Jenggot Pekalongan City. E3S Web of Conferences. 2018, 31, 9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdharini, C.; Setyaningtyas, T.; Riyani, K. Comparative study of Fe2+/H2O2/CuO/Vis and Fe2+/H2O2/CuO for phenol removal in batik wastewater under visible light irradiation. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2021, 1918, 32004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitria, F. L.; Dhokhikah, Y. Removal of chromium from batik wastewater by using kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) with bed evapotranspiration. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2019, 243, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, M.; Wikaningrum, T. The Bacteria Addition Study to Batik Wastewater Industries In pH Performance, and Removal of Ammonia and COD. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2022, 995, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusa, R. F.; Sari, D. N.; Afriani, F.; Sunanda, W.; Tiandho, Y. Effect of electrode numbers in electrocoagulation of Batik Cual wastewater: analysis on water quality and energy used. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2022, 599, 12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.; Tomasowa, R.; Hiemmayani, V. Natural dyes batik gallery with waste management in Kampung Palbatu Tebet. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 794, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M. A. K. M.; Ibrahim, S.; Subberi, N. I. F. M.; Kantasamy, N.; Fatimah, I. Application of Cationic Surfactant Modified Mengkuang Leaves (Pandanus atrocapus) for the Removal of Reactive Orange 16 from Batik Wastewater: A Column Study. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology. 2021, 20, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Khalik, W. F.; Ho, L.-N.; Ong, S.-A.; Voon, C.-H.; Wong, Y.-S.; Yusuf, S. Y.; Yusoff, N. A; Lee, S.-L. Enhancement of simultaneous batik wastewater treatment and electricity generation in photocatalytic fuel cell. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2018, 25, 35164–35175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchtasjar, B.; Hadiyanto, H.; Izzati, M.; Vincēviča–Gaile, Z.; Setyobudi, R. H. The Ability of Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crasipes Mart.) and Water Lettuce (Pistia stratiotes Linn.) for Reducing Pollutants in Batik Wastewater. E3S Web of Conferences. 2021, 226, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R. S.; Airun, N. H. The effect of particle size and dosage on the performance of Papaya seeds (Carica papaya) as biocoagulant on wastewater treatment of batik industry. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2021, 1087, 12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadyanti, E.; Wiyono, A. Constructed Wetland with Rice Husk Substrate as Phytotechnology Treatment for Sustainable Batik Industry in Indonesia. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2020, 1569, 42018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmaniah, G.; Mahdi, C.; Safitri, A. Biosorption of Synthetic Dye from Batik Wastewater Using Trichoderma viride Immobilized on Ca-Alginate. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2019, 1374, 12007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezagama, A.; Sutrisno, E.; Handayani, D. S. Pollution Model of Batik and Domestic Wastewater on River Water Quality. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2020, 448, 12074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulthonuddin, I.; Herdiansyah, H. Sustainability of Batik wastewater quality management strategies: analytical hierarchy process. Applied Water Science. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djunaidi, M.; Setyaningsih, E. Pemilihan Alternatif Penghematan Energi pada Proses Produksi Batik Cap dengan Menggunakan Metode Mcdm-Promethee. Spektrum Industri, 2017, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrayani, L.; riwiswara, M. The implementation of green industry standard batik industry to develop eco-friendly. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 12081–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, F. A.; Roslan, A. N.; Zakaria, Z. A.; Zaini, M. A. A.; Pusppanathan, J.; Talib, C. A. Environmental Awareness in Batik Making Process. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirait, M. Cleaner production options for reducing industrial waste: the case of batik industry in Malang, East Java-Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2018, 106, 12069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trihanondo, D.; Endriawan, D.; Haryotedjo, T; Putra, G. M.; Machfiroh, R. Redefining Cirebon batik into an environmentally friendly icon of West Java. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2021, 1098, 52011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A. A.; Bloemer, J.; van Riel, A. C. R.; Essers, C. Institutional Barriers and Facilitators of Sustainability for Indonesian Batik SMEs: A Policy Agenda. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, B.; Permana, C. T. Sustainability-oriented innovation (SOI) in the cultural village: an actor-network perspective in the case of Laweyan Batik Village. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. 2020, 11, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardani, S. D. A.; Kurnani, T. B. A. Assessment tool to understand the readiness of Batik SMEs for Green Industry. E3S Web of Conferences. 2021, 249, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubiena, G. F.; Ma’ruf, A. Development of an Assessment Model for Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Batik Industry. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2018, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawi, N. C.; Al Mamun, A.; Daud, R. R. R.; Nasir, N. A. M. Strategic orientations and absorptive capacity on economic and environmental sustainability: A study among the batik small and medium enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya, A. B.; Andiani, R.; Siregar, A. P.; Prasada, I. Y.; Indana, F.; Simbolon, T. G. Y.; Kinasih, A. T.; Nugroho, A. D. Challenges, open innovation, and engagement theory at craft SMEs: Evidence from Indonesian batik. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widhiastuti, A.; Muafi, M. The effect of environmental commitment on circular economy implementation: A study on Small Batik Industry in Sleman Regency. International Journal of Business Ecosystem & Strategy. 2022, 4, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sunarjo, W.A.; Manalu, V.G.; Adawiyah, W.R. Nurturing Consumers’ Green Purchase Intention on Natural Dyes Batik During Craft Shopping Tour in The Batik City of Pekalongan Indonesia. Geoj. Tour. Geosites. 2021, 34, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untari, R. How do Batik Natural Dyes Crafter Spread Their Green Value (Case Studies on Batik Gemawang and Batik Warna Alam Si Putri). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021, 940, 12073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

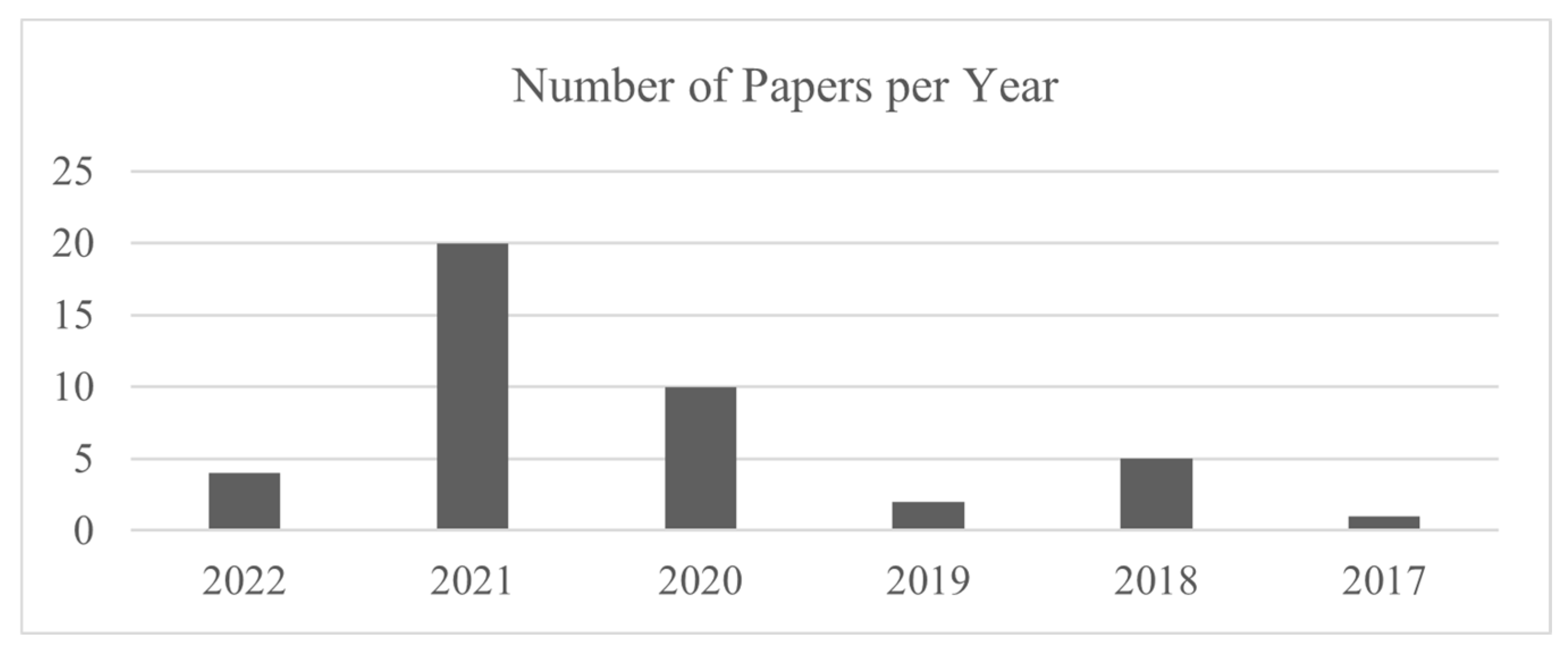

| Year | Conference | Journal |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 1 | 3 |

| 2021 | 14 | 6 |

| 2020 | 7 | 3 |

| 2019 | 1 | 1 |

| 2018 | 4 | 1 |

| 2017 | - | 1 |

| Production: Materials | Production: Dyeing | Production: Waste | Production: Full Process | Organisa-tion | Marketing | Finance |

| 4 | 8 | 15 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Year | Producti-on: Materials | Producti-on: Dyeing | Producti-on: Waste | Producti-on: Full process | Organisa-tion | Marketing |

| 2022 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | - |

| 2021 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2020 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | - |

| 2019 | - | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| 2018 | - | - | 3 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 2017 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Province | Area | Paper |

| DKI Jakarta | 1 | |

| West Java |

Jababeka | 1 |

| Cirebon | 1 | |

| Indramayu | 1 | |

| Central Java |

Pekalongan | 3 |

| Sukoharjo | 2 | |

| Semarang | 1 | |

| Klaten | 2 | |

| Surakarta | 3 | |

| Banyumas | 2 | |

| Yogyakarta |

Sleman | 1 |

| Yogyakarta | 1 | |

| East Java |

Surabaya | 1 |

| Jember | 2 | |

| Malang | 2 | |

| Not specified | 1 | |

| Bangka Belitung | 1 | |

| West Sumatera | 1 | |

| Not specified | 8 | |

| Total | 35 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).