1. Introduction: tulou (the Rammed Earth Dwelling) of Chaozhou, Guangdong(Canton)Province, China

A recent United Nations study revealed that approximately one-third of global structures are constructed using earth, highlighting the widespread and enduring use of this material in building practices worldwide [

1]. Tulou, a type of rammed earth dwelling identified in China, represent a significant aspect of global architectural heritage, as they are crafted from raw earth and serve as a valuable component of human cultural heritage. Due to their distinct and unparalleled form, they are often referred to as “China’s most extraordinary folk dwellings [

2].

Tulou, distinctive residential structures predominantly found in the neighboring regions of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi provinces in China, were constructed between the 14th and 20th centuries. Derived from the Chinese characters (tǔ “土” «earth» and lóu “楼” «multi-storey house»), the term "tulou" signifies multi-storey dwellings built with earth materials such as rammed earth or adobe. These structures are celebrated as the culmination of centuries of wisdom, reflecting the historical and social context of their time. They were designed to harmonize with the natural environment, adapt to local geographical conditions and climate, and efficiently utilize available resources to fulfill both physical and spiritual needs.

Tulou are often regarded as prime examples of sustainable architecture, boasting features such as the use of local materials like rammed earth, earth blocks, stone, and wood; the employment of traditional construction techniques; low energy consumption during construction; and the ability for discarded materials to seamlessly integrate with the natural environment. These unique structures have garnered significant international attention, with 46 tulou in Fujian Province being designated as World Cultural Heritage sites. Additionally, numerous studies have been conducted to explore various aspects of tulou, including their typology, spatial organization, materials, construction technique, structural characteristics, and geographic distribution [

3].

Nonetheless, the research primarily consists of case studies, with the majority of subjects focused in Fujian Province. Additionally, a small portion is situated in the Hakka region of Jiangxi Province, while only a few involve the Guangdong Tulou. In fact, most studies tend to equate "tulou" solely with earthen Hakka structures in Fujian [

4].

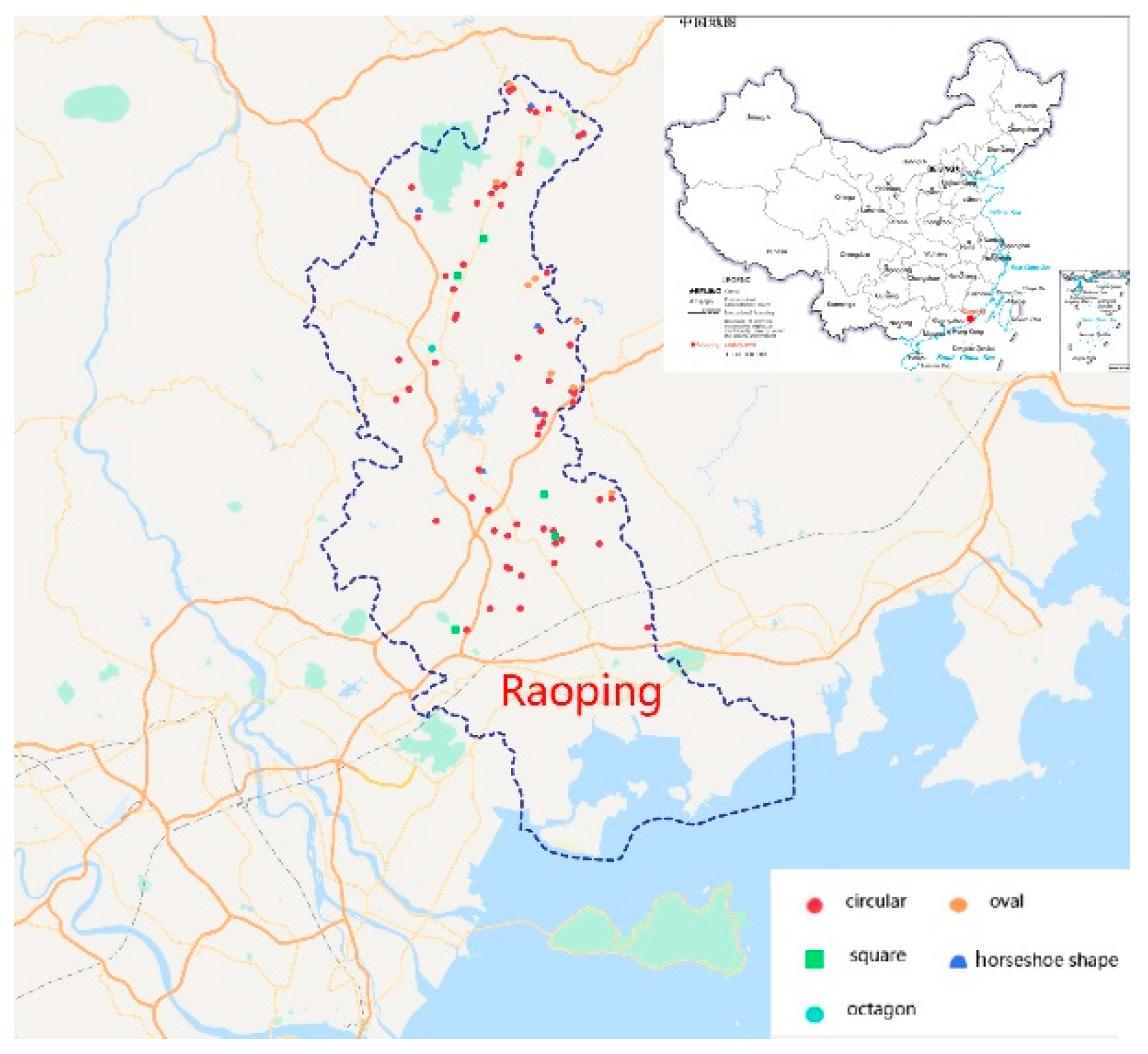

Tulou in Guangdong are predominantly found in Raoping County, Chaozhou City, which shares a border with Fujian Province. As per the

Raoping Xianzhi (Records of Raoping County), traditional dwellings in the Raoping mountainous area were mainly tulou. Prior to the Reform and Opening-up, 781 tulou were documented, dispersed across 16 towns. Between 2007 and 2011, during the third national survey of immovable cultural relics, 217 tulou were registered in Raoping County. This included one national key cultural relic protection unit (“道韵楼”, Daoyun Lou), nine provincial cultural relic protection units, 10 county-level cultural relic protection units, and 63 immovable cultural relics (

Figure 1,

Figure 2).

Situated within a cultural transition zone, Raoping County borders the core region of Hakka culture (Meizhou City) to the north and the heartland of Fulao

1[

5] culture (Chaozhou City) to the south [

6]. The Raoping tulou are not only abundant in quantity but also boast unique regional characteristics in shape, form, structure and spatial pattern, by taking Minnan unit Tulou

2 as the basic prototype, while being noticeably influenced by the Hakka “Wei Long House”

3 (“围龙屋”, round dragon house). Raoping Tulou offer a glimpse into the rich diversity of “standard” tulou dwellings, shaped by the interplay between Hakka and Fulao ethnic cultures. This insight allows us to appreciate the remarkable adaptability and broad applicability of tulou residential structures, highlighting their significant cultural and architectural value, which merits systematic study.

As economic prosperity drives young and middle-aged individuals to seek employment in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, rural communities face severe depopulation, leading to the irreversible decline and abandonment of Raoping Tulou. This shift also results in the loss of associated knowledge and collective memory [

7]. Inappropriate technical reinforcements, along with incongruous modifications and additions for various purposes and adaptations to modern living conditions, are prevalent even among those tulou officially designated as protected cultural relics [

4,

8].

Hence, an in-depth investigation into the morphological and spatial attributes of Raoping tulou is of utmost importance. Lessons from the past have shown that only through scientific and genuine research can we develop effective conservation and development strategies, thereby preventing further societal and human-induced harm to this architectural legacy [

4].

By conducting thorough field surveys and employing a blend of qualitative and quantitative statistical analyses, this study offers a comprehensive overview of Raoping Tulou's features, including their geospatial distribution, spatial organization, and the scale of their buildings and residential units, as well as the external enclosure structures and communal spaces and amenities. The insights gained from this research can contribute to the academic understanding of tulou and global earthen architectural heritage. Moreover, it delves into the uniformity and adaptable variations of tulou dwellings and residential units in relation to differing economic investments, site dimensions, and user group sizes. This accurately showcases the practicality and adaptability of ancient residential architecture. The versatile spatial planning and design methodology of tulou, as unveiled in this study, holds substantial relevance for contemporary architectural design.

Figure 1.

Tulou in Raoping County, Chaozhou City, Guangdong Province, China.

Figure 1.

Tulou in Raoping County, Chaozhou City, Guangdong Province, China.

Figure 2.

Donghua Lou, Nanyang Lou, Fuhai Lou in Shangrao Town.

Figure 2.

Donghua Lou, Nanyang Lou, Fuhai Lou in Shangrao Town.

2. Methodology

In general, the absence of direct written records for folk architectural heritage necessitates that associated research primarily depends on fieldwork, which constitutes both the challenge and the allure of this investigation. In this study, 83 tulou cases were chosen, encompassing all cultural relic protection units and immovable cultural relic tulou in Raoping County. Comprehensive field surveys, high-definition satellite image analysis, architectural mapping, photography, and semi-structured interviews with villagers were conducted to acquire first-hand architectural and oral historical data for subsequent qualitative and quantitative assessments.

This paper initially reconstructs the historical and social contexts of tulou construction in the Chaozhou area by examining historical documents and local chronicles, and it uncovers the objectives and tactics employed in building tulou. Subsequently, the geospatial distribution of the 83 tulou is assessed on a map, and the form and scale (covering area, number of residential units/rooms) of tulou are quantitatively examined. Additionally, the spatial arrangement, external enclosed space, and distribution of ancestral halls/public halls are qualitatively scrutinized. Lastly, the layout of residential units and their variants under different scales (width and depth) are qualitatively analyzed and summarized.

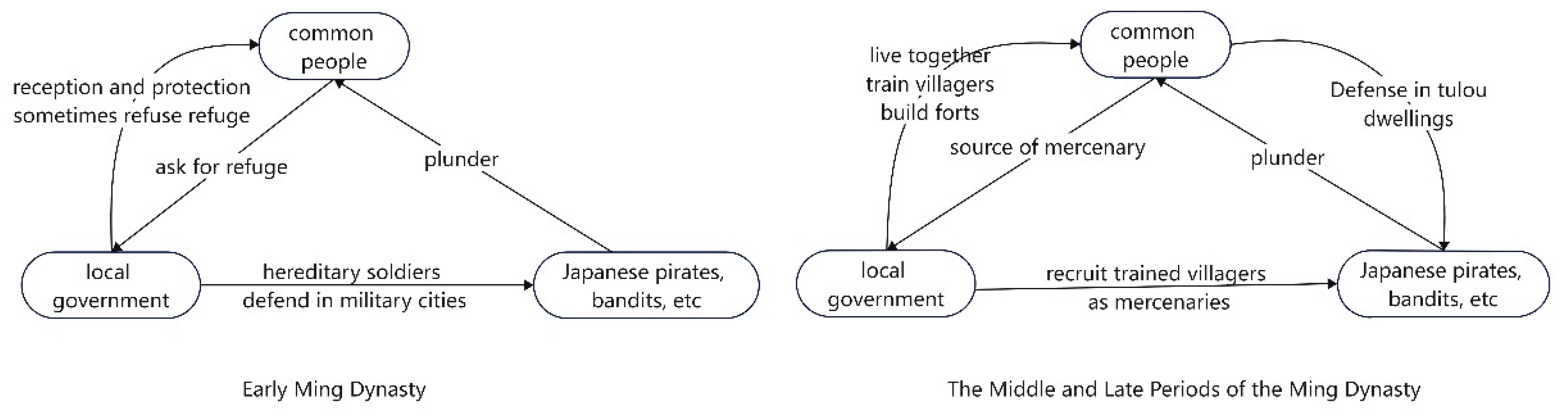

3. The construction of folk collective defense dwellings in Chaozhou

In ancient times, conflicts among nations, tribes, and clans arose globally due to scarce resources. Persistent conflicts led to the development of various defensive structures. For instance, during the medieval period in Germany, over 10,000 military castles were built. In southern China, civilians constructed Tulou and Weizhai (“围寨”, walled villages), which served as both dwellings and defensive structures amid widespread turmoil. Typically, Weizhai were built in coastal plains, while Tulou were constructed in inland mountainous and hilly regions [

9].

The ethnic groups responsible for these fortified buildings were forced to migrate from the Central Plains to southern China between the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty. The Hakka people primarily settled in the border regions of Guangdong, Fujian, and Jiangxi provinces, while the Fulao people mainly resided in southern Fujian and eastern Guangdong provinces. However, these migrants did not find the peace and prosperity they sought. Instead, they faced challenging agricultural conditions due to the mountainous terrain and limited land, as well as a chaotic social environment.

The defensive architecture during this period was mainly represented by the Wufeng Lou (“五凤楼”), which was a residence built and inhabited by a single wealthy family. However, during the Ming Dynasty, tulou - collective dwellings funded and shared by multiple families (usually belonging to the same clan) - quickly emerged as a popular and dominant residential building type. Tulou dwellings reflect the instinctive demands for security of common people during turbulent periods instead of the rich and powerful people as many tourism campaigns suggested [

10].

In the mid-to-late 14

th century, China’s Ming Dynasty had just been established. Japan was then in a state of war between the Southern and Northern Dynasties, and while the Northern regime was expected to engage in friendly intercourse with the Ming, the Southern regime continued to encroach on the Chinese coast. After the defeat of the Southern regime, large numbers of Japanese samurai fled to the sea and became well-organized pirates. From Liaodong to Guangdong, China’s coastal regions suffered a prolonged period of depredations and massacres, particularly in the provinces of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong [

3].

Zhu Yuanzhang, the Ming Dynasty emperor, on the one hand imposed maritime prohibition to block contact between the inland and sea, "Forbid coastal dwellers going to sea without permission", "Forbid coastal dwellers communicating with foreigners", "No fishing around the sea" [

11]. On the other hand, he ordered the construction of a coastal defense system including pearl-chain form military cities (“卫所”,Wei Cheng and its jurisdictional Suo Cheng), island fortresses, and watchtowers along the overall coast from Liaodong to Guangxi provinces, as well as setting up guards at all inland estuary, transport hubs, important towns, and small islands.

The maritime prohibition led to the impoverishment of coastal communities reliant on salt and fishing for their livelihoods, forcing them to engage in risky dealings with pirates. Concurrently, the wealthy coastal gentry, who had previously profited from maritime trade and salt production, accumulated wealth through collaboration with pirates [

12]. This collusion between internal and external forces, underground trading, and unresolved commercial disputes all contributed to armed conflicts, resulting in the infestation of Japanese pirates, sea thieves, and mountain bandits in southeastern coastal regions. This event is historically referred to as the “Jiajing Rebellion” (嘉靖倭乱), which denotes a series of brutal massacres during the Jiajing period (1522-1566).

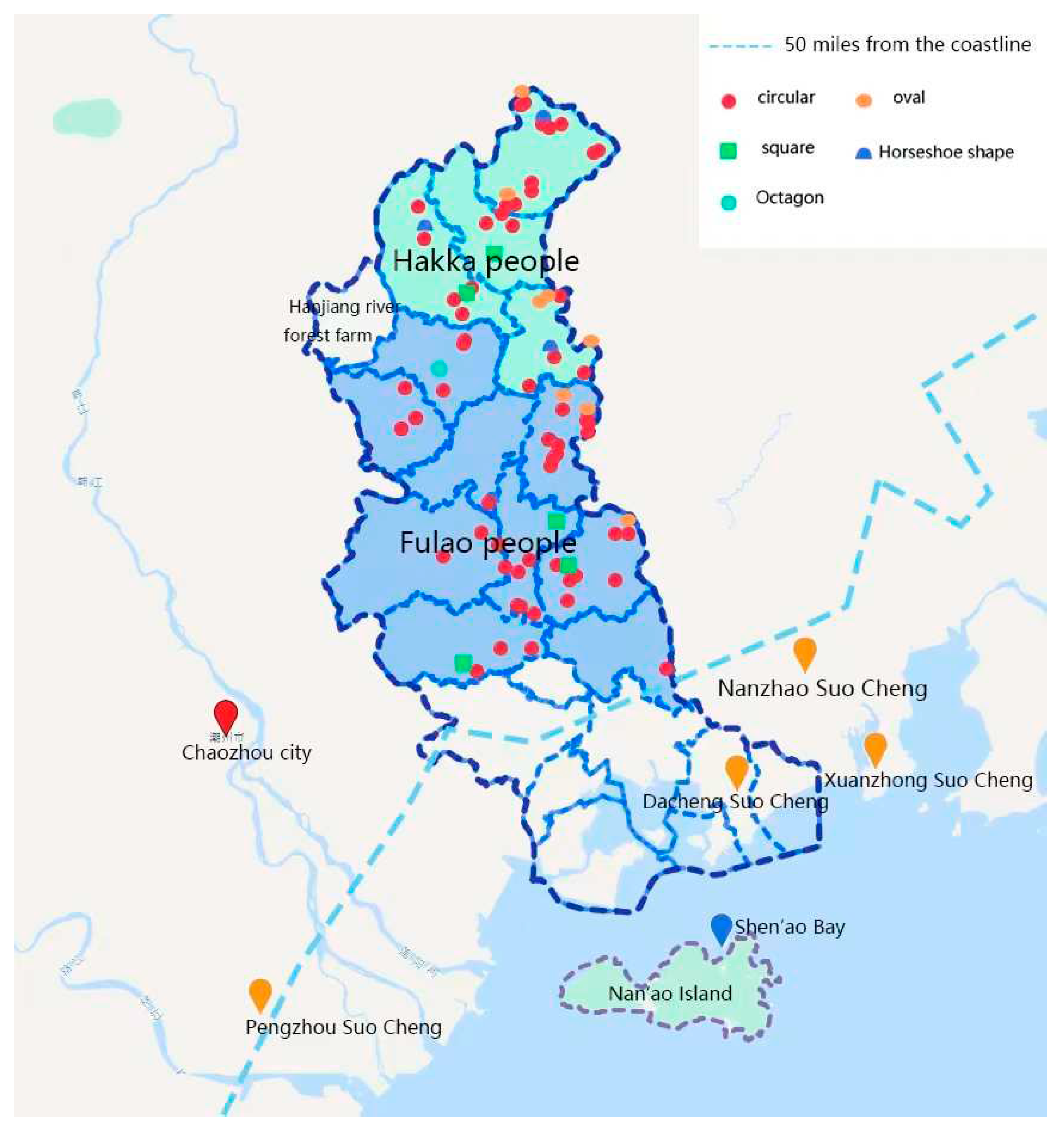

Raoping County, part of Chaozhou city, is nestled between mountains and sea. It safeguards the Huanggang River estuary and is home to fertile inland towns and villages. The bay north of Nan-ao Island functions as a natural deep-water harbor, offering the sole navigable passage from Guangdong to Fujian - an advantage exploited by Japanese pirates. As a result, Chaozhou became the region most severely impacted by Japanese piracy, with historical records detailing an alarming number of attacks and casualties. The extended occupation of Nan-ao Island by Japanese pirates posed a significant threat to inland areas [

13](

Figure 3).

Regrettably, civilians could not always seek refuge in officially constructed, military-fortified cities during pirate invasions. According to the Dongli Annals (东里志), in Ming Hongwu’s thirty-first year (1398), Japanese pirates assaulted the Dongli Peninsula in Raoping, Chaozhou. On the peninsula stood a military Suo city, “Da Cheng Suo Cheng” (大城所城), which was officially built to defend against Japanese pirates. Local residents fled to “Da Cheng Suo Cheng” seeking refuge. The east gate military officer, Gu Shi (顾实), opened the gate to admit refugees. However, three other officers guarding the west, south, and north gates refused entry, resulting in the brutal deaths of numerous civilians[

14].

In the early Ming period, the coastal defense system played a significant role in combating piracy and maintaining regional stability to a certain extent. However, by the middle of the Ming dynasty, increasing political corruption led to a dramatic decline in the military’s combat capabilities. Many soldiers deserted as rations were cut and their designated farmland (“Tuntian”, 屯田) intended for supporting their livelihoods was heavily seized by higher officials. According to Guangdong Tongzhi (广东通志), military cities such as Lianzhou (廉州), Leizhou (雷州), Shendian (神电), Guanghai (广海), Nanhai (南海), Jieshi (碣石), and Chaozhou (潮州) had a total of 8,281 soldiers during the Jiajing period (1507-1567), with a shortage of 69.8%. In this social context, the common people had no choice but to organize themselves into ethnic groups for collective defense.

China’s coastal military system transitioned from the Weisuo Zhi (卫所制, hereditary soldiers defending coastal military cities) to the Mubing Zhi (募兵制, paid volunteers recruited to join the army for an agreed period). Coastal officials proposed training villagers as soldiers for self-protection, and these trained rural soldiers became an essential part of the Mubing group [

15].

Local officials actively implemented the policy of “building civil forts and training civilian soldiers” to ensure local security, providing authoritative support for the construction of defensive dwellings. The local government also encouraged smaller villages to merge and defend collectively [

16]. For instance, scholar-official Huo Tao suggested that local people in Fujian and Guangdong should organize and build forts for self-defense [

17]. Consequently, local clans became more closely connected based on kinship and geography, and the militarization of grassroots society rapidly increased [

18].

The “training villagers” and “building forts” policy led to significant transformations in residential styles and rural landscapes in Guangdong and Fujian since the Jiajing period. In the mountainous and hilly regions bordering Fujian and Guangdong, large tulou dwellings with both defensive and communal living functions flourished (

Figure 4).

By the end of the Ming Dynasty, a power struggle between the remnants of the Ming Dynasty and the Qing regime resulted in social unrest and frequent uprisings in Fujian and Chaozhou areas. Large-scale riots, banditry, and conflicts among clan groups competing for limited resources and honor contributed to the enduring prominence of defense-dwellings until modern times [

19]. Consequently, a clan-based collective defense system and corresponding tulou collective residential buildings were established, sustained by group forces and playing a long-term role.

Figure 3.

Tulou in Raoping County.

Figure 3.

Tulou in Raoping County.

Figure 4.

The social context behind the prevalent of tulou.

Figure 4.

The social context behind the prevalent of tulou.

4. Geospatial distribution of Chaozhou tulou

4.1. Distributed along rivers

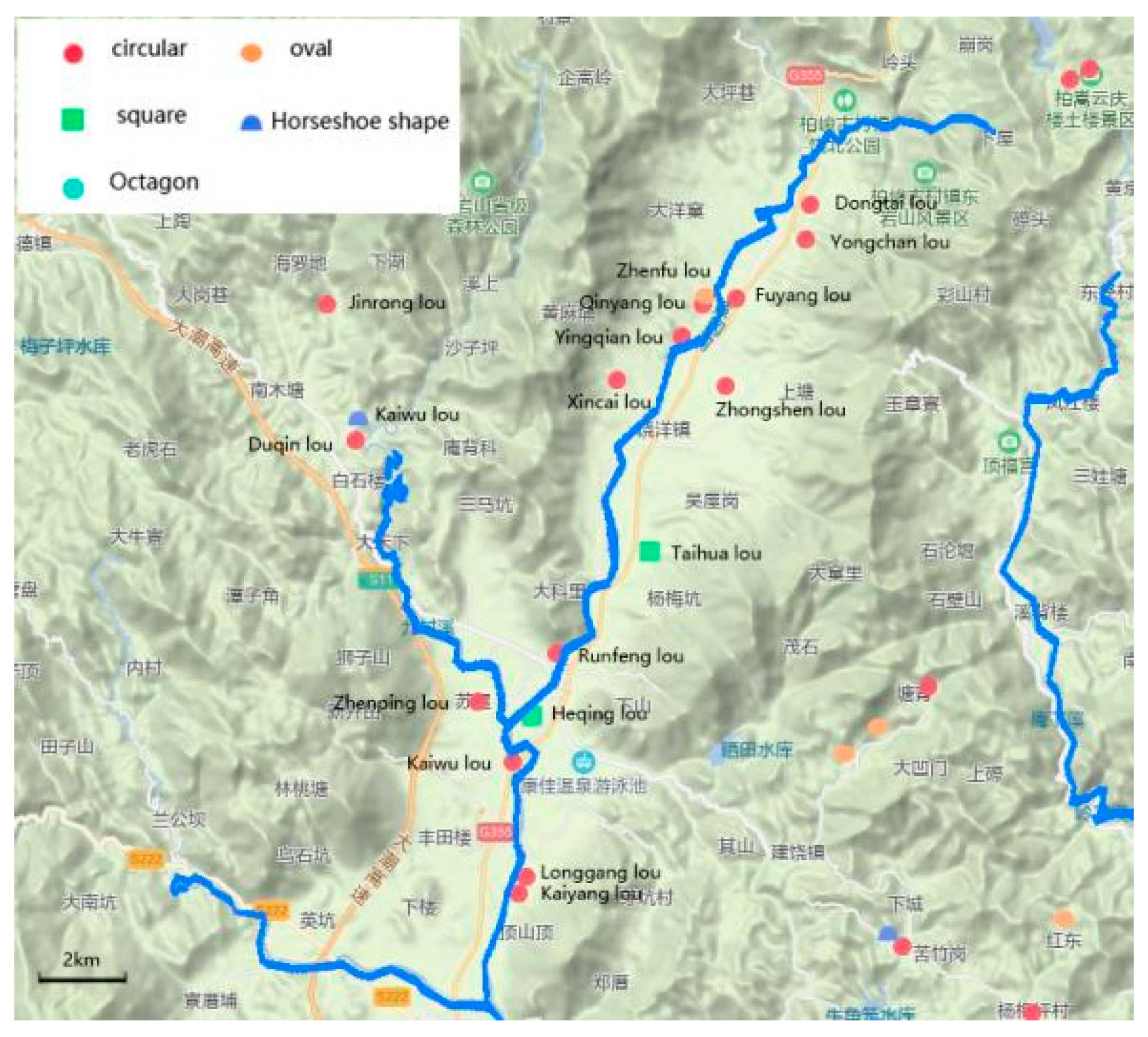

In the mountainous region of northern Raoping, tulou are typically found in fertile valleys along rivers or streams, accompanied by carefully terraced cultivated land. In the hills and plains of central Raoping, tulou continue to be distributed along rivers, which serve as communication and trade routes and provide essential water resources for agricultural fields (

Figure 5). Generally, Raoping tulou are primarily dispersed along both sides of the Huanggang River and its tributaries: Songnanshui, Jiucun Creek, Chering Creek, Xintang Creek, Dongshan Creek, Fubin Creek, Xinwei Creek, Zhangxi River, and Lianraao Creek. The building site, orientation, shape, and other aspects of tulou are typically determined according to traditional Chinese architectural planning theory, which is grounded in Feng-shui principles.

4.2. Distributed 25km off the coast

According to the map, Raoping tulou are uniformly distributed throughout the county, with the exception of a 50 “li” (里, equivalent to 0.5 kilometers) area from the coastline. In 1636, the newly established Qing government sought to eliminate Zheng Chenggong’s forces, who had been defeated in the regime war and retreated to Taiwan Island. To achieve this, they issued a strict “Maritime Trade Ban”, prohibiting all forms of private maritime trade in an effort to cut off Zheng’s supplies. However, when this ban failed to produce the desired outcome, the government implemented a “Coastal Evacuation Decree” in 1661, forcing coastal residents to relocate 30-50 “li” inland. The Qing government employed aggressive tactics to drive out coastal inhabitants, often resorting to the destruction of homes, crops, and other essential resources. Historians have verified that the “Coastal Evacuation Decree” inflicted significant damage on residential structures within dozens of kilometers of the coast, resulting in the complete demolition of coastal tulou buildings [

20].

Following the “Return to the Coast” decree in 1689, the Fulao clan resettled in their original coastal locations, sparking a new wave of construction. However, during this period, the Qing dynasty was stable and society was peaceful. Consequently, people opted to construct courtyard dwellings that offered greater comfort and privacy, rather than rebuilding tulou. This explains the current absence of tulou near the coast, despite the frequent conflicts that occurred during the Ming Dynasty (

Figure 3).

5. Space layout of tulou

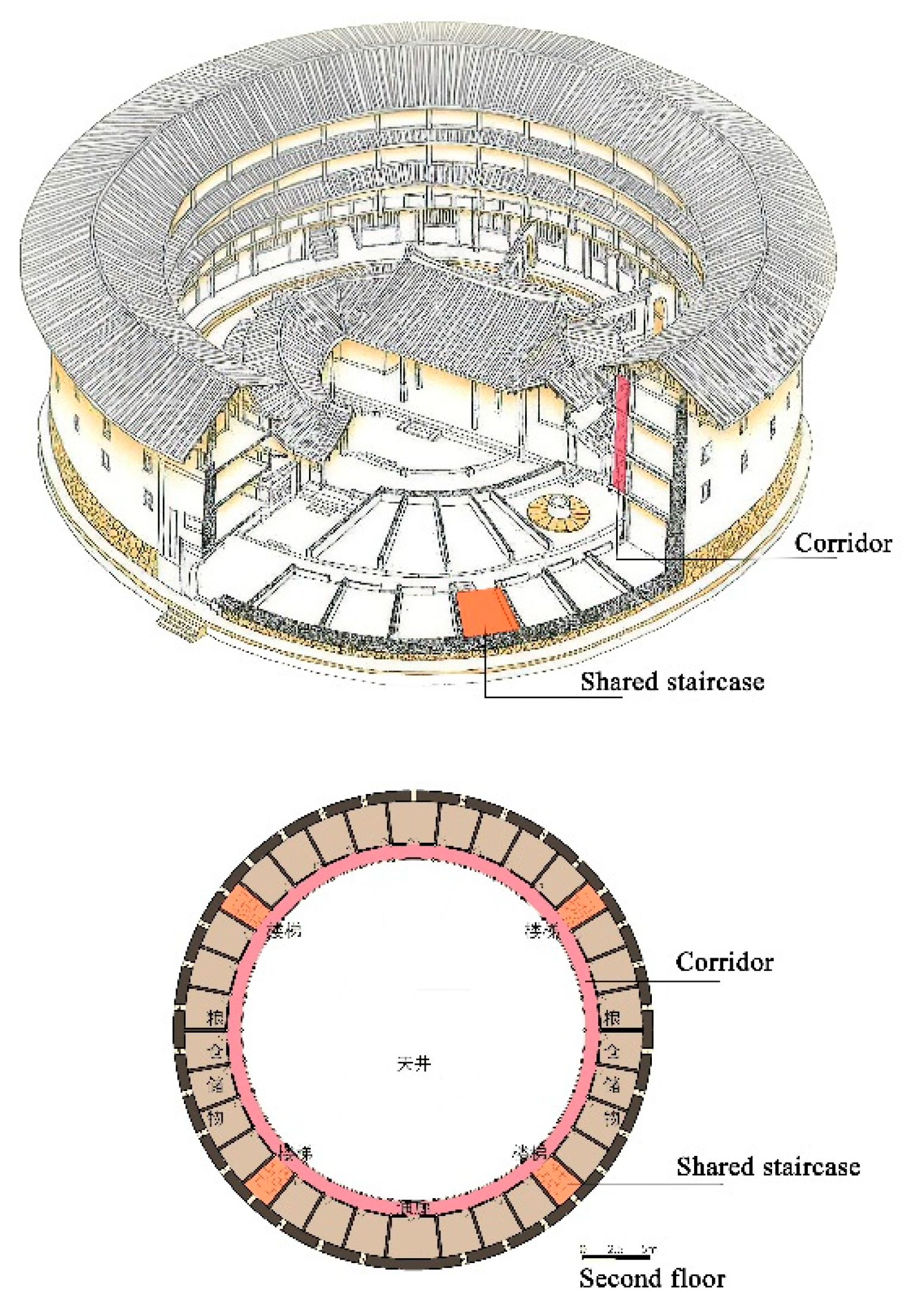

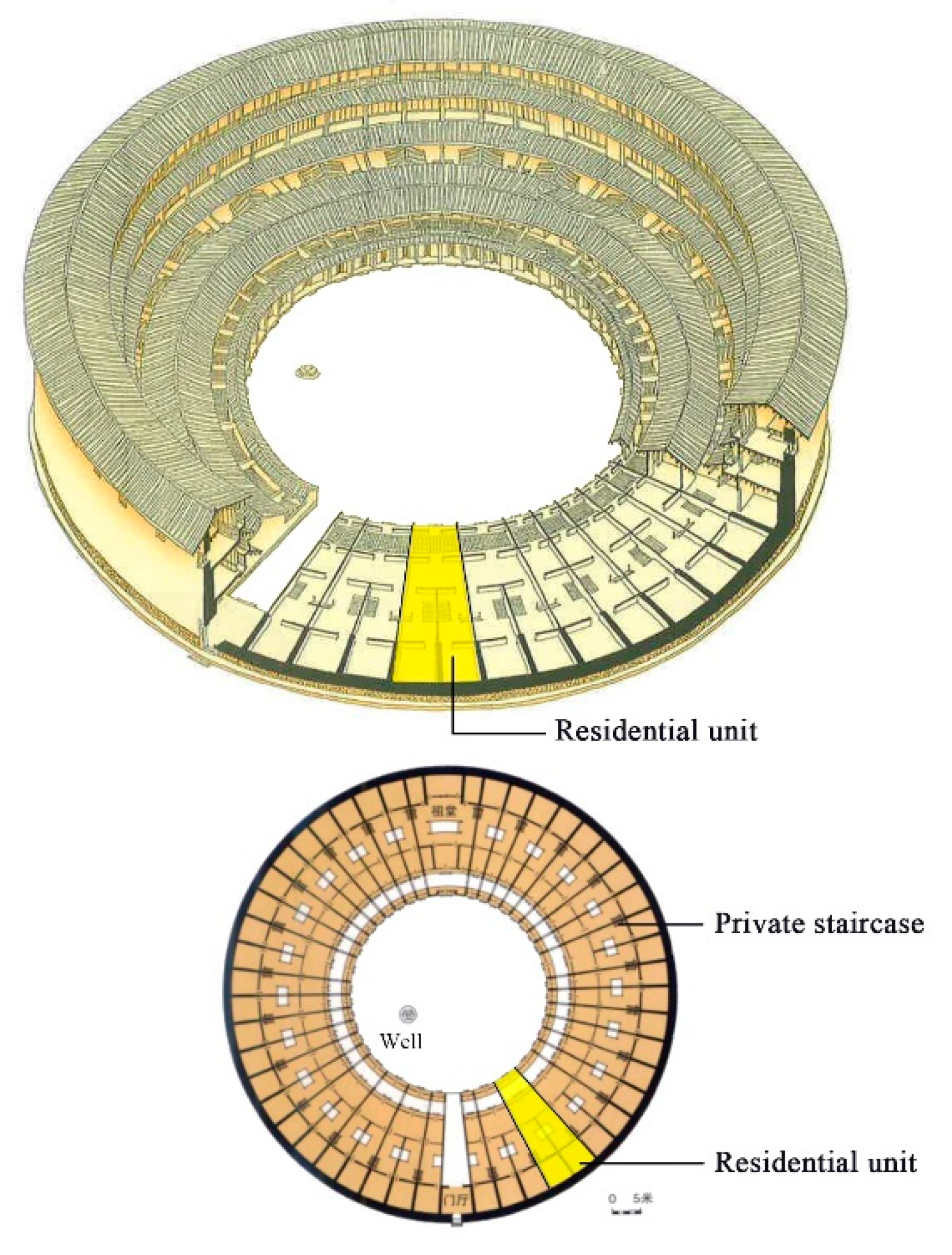

5.1. Overall spatial layout

Although tulou display a variety of external appearances, such as circular, oval, square, octagonal, and half-moon shapes, their internal spatial layouts exhibit a remarkable consistency. These layouts can be categorized into two distinct types in China: Hakka Tulou and Minnan Tulou. Hakka Tulou is characterized by an inner corridor layout, where space is organized around circular corridors with multiple communal staircases (

Figure 6). In contrast, Minnan Tulou features a unit layout composed of identical, sequential residential units, each with its own separate entrance and private staircase that extends across all floors [

21](

Figure 7).

In both types, an equal amount of private space is allocated to each small family to maintain a harmonious collective life and demonstrate equality among family members. However, the two distribution methods have their respective pros and cons. In Hakka tulou, the rooms designated for each family are closely interwoven, fostering unity within the larger family. This arrangement encourages close family cooperation in overall maintenance and prevents arbitrary room sales among family members, reflecting a preference for sacrificing small-scale privacy for the benefit of larger families. In contrast, the Fulao tulou offers greater independence and privacy, creating more comfortable living conditions. Additionally, individuals can make independent decisions regarding the timing and selection of building materials for their housing construction based on their own family’s economic situation. However, this can make it challenging to collaborate on maintaining public affairs and prevent residents from converting, selling, or abandoning their units, which may not promote long-term family unity.

According to the field survey results, all tulou in Chaozhou use a unit layout. The residential units are separated by radial load-bearing walls constructed using pisè or adobe techniques, with floor purlins inserted into the middle and roof purlins placed on top of the walls. In Hakka tulou, rooms are distinguished by wooden frames and non-load-bearing adobe partitions. Thanks to the load-bearing walls in the longitudinal direction, each residential unit can be extended without restriction and accommodate more functions. For example, the residential unit may have a separate entrance hall, living room, semi-open yard and patio, and sometimes a private ancestor worship space - all shared by the big family in tulou with an inner corridor layout.

It is worth noting that the two types of tulou employ distinct external and internal scaling systems. Upon approach, one is confronted with towering walls and a colossal structure in stark contrast to the human body, evoking feelings of self-insignificance. This external manifestation reflects tulou’s defensive nature, inspiring awe and conveying an unyielding invincibility that can create a sense of oppression - an effect of super-size. This measure is external, against an external enemy. However, once inside the tulou, it becomes a completely different world where the scale system is centered around people: with unit widths of 2-4 meters, delicate wooden doors and windows, appropriate heights, pleasant small scales, and friendly building materials all creating an ideal living environment for tulou residents. The extensive treatment of the exterior space contrasts with the intricate treatment of the interior space, which is a prominent feature and charm of tulou architectural spaces [

22].

Figure 6.

Hakka Tulou - inner corridor layout (Huaiyuan Lou, Nanjing County, Fujian province)22,page45.

Figure 6.

Hakka Tulou - inner corridor layout (Huaiyuan Lou, Nanjing County, Fujian province)22,page45.

Figure 7.

Minnan Tulou - unit layout (Longjian Lou, Pinghe County, Fujian province)22,page50.

Figure 7.

Minnan Tulou - unit layout (Longjian Lou, Pinghe County, Fujian province)22,page50.

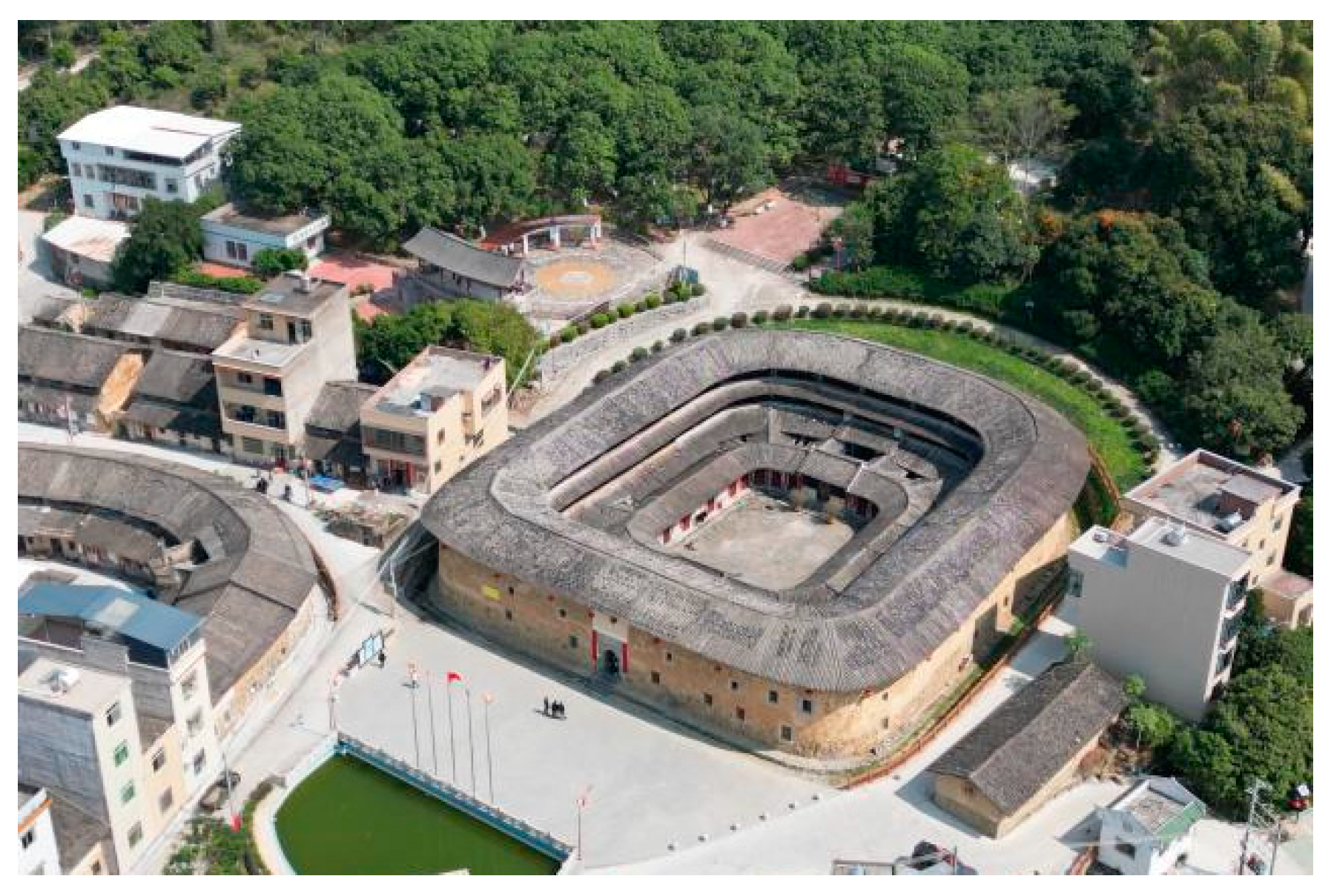

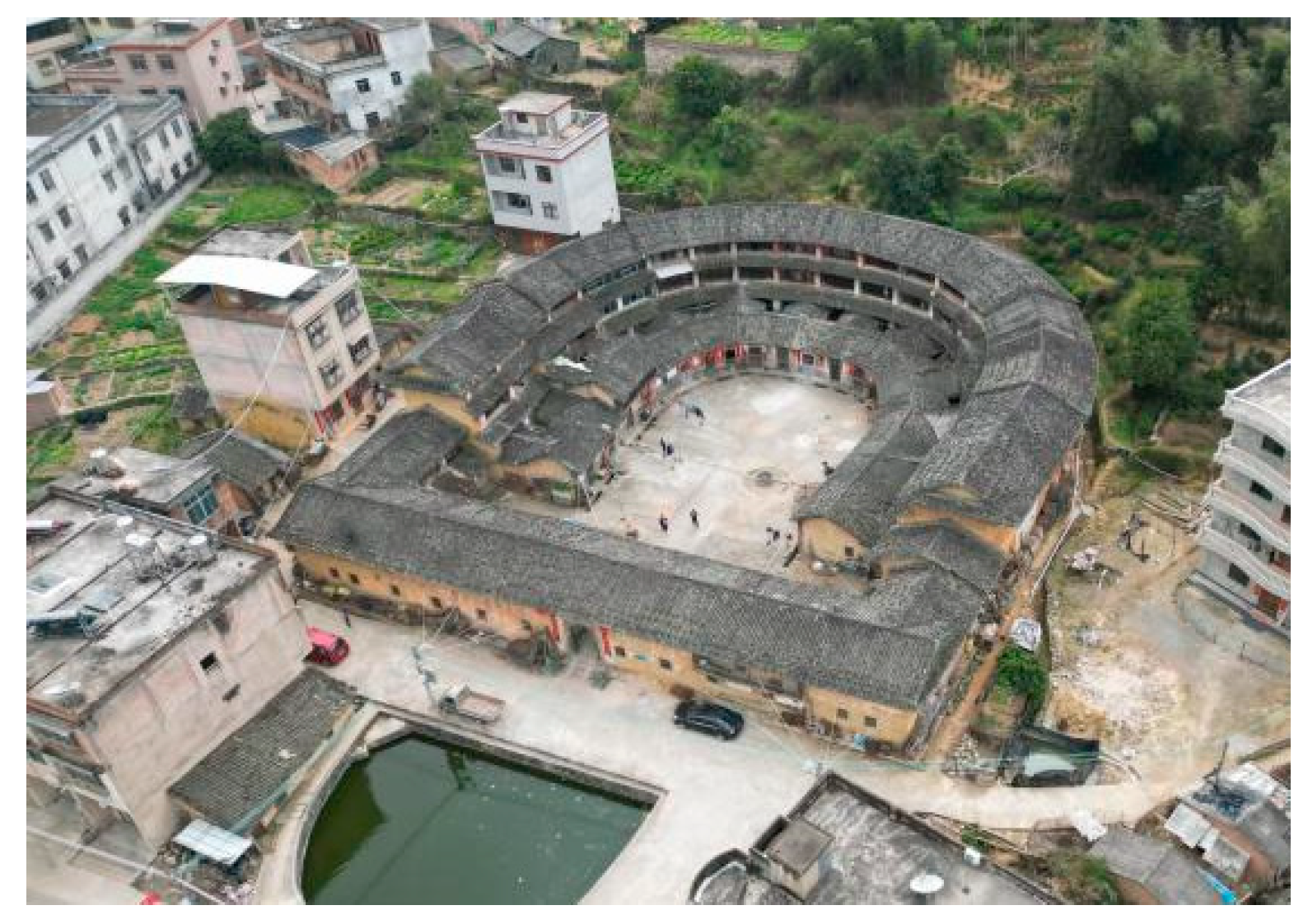

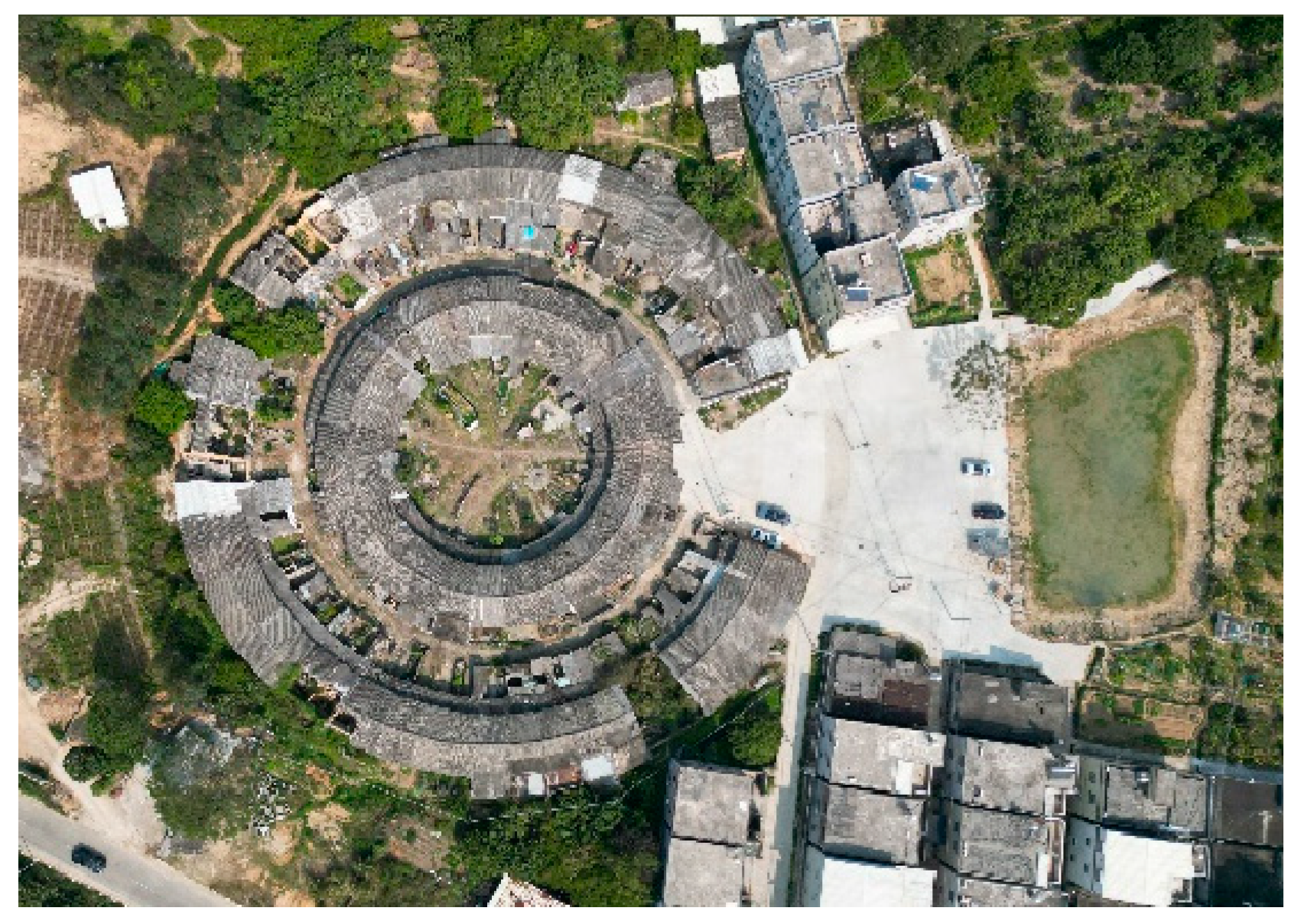

5.2. Shape and Scale

The sizes of Raoping tulou exhibit significant variation, with the smallest ones covering an area of approximately 400 square meters, while the larger ones can span up to 7,000 square meters. These tulou come in a variety of shapes, including round, oval, square, and horseshoe. Typically, they stand two or three stories tall and house communities of around 150 to 400 individuals [

23] (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11).

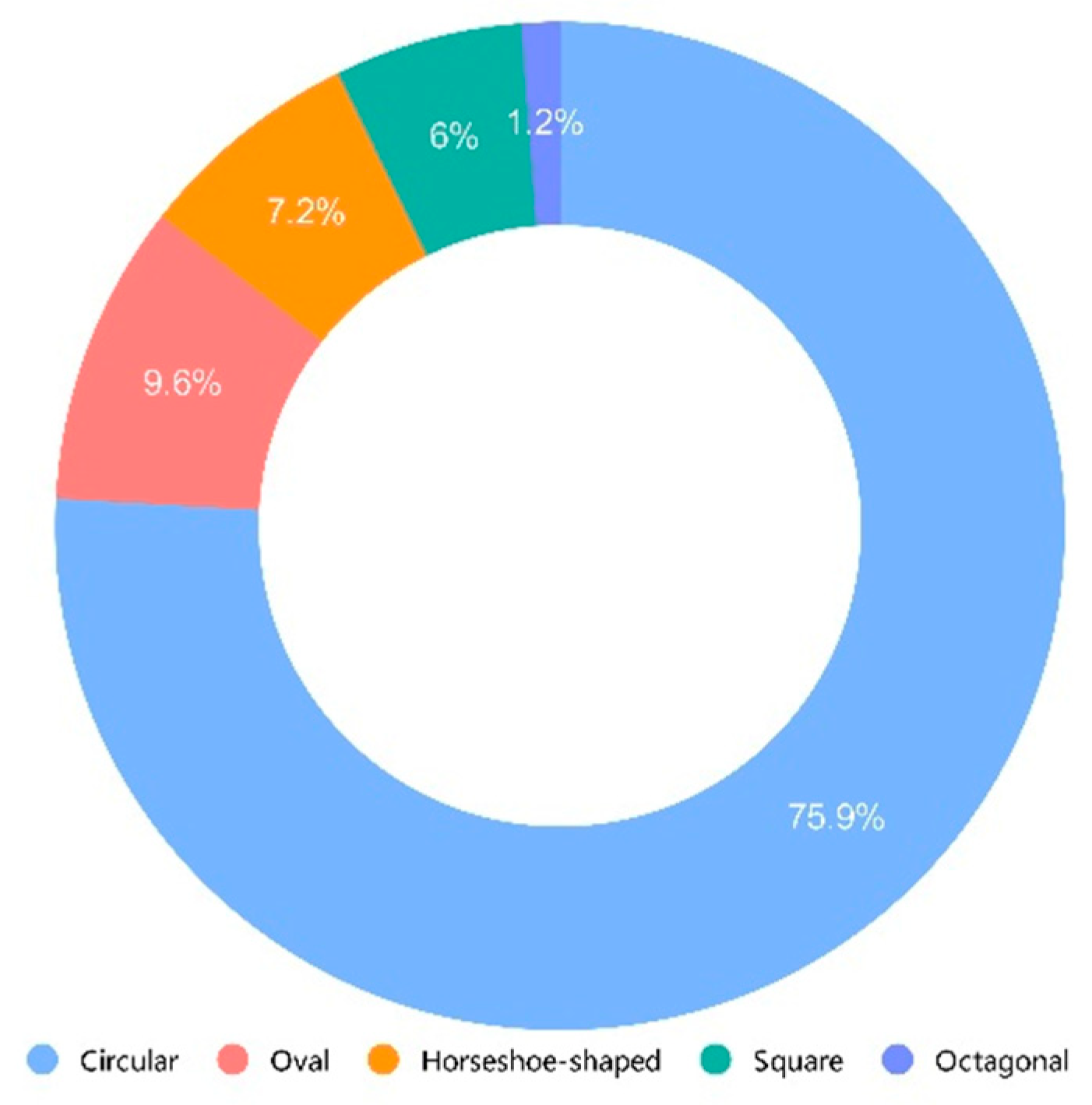

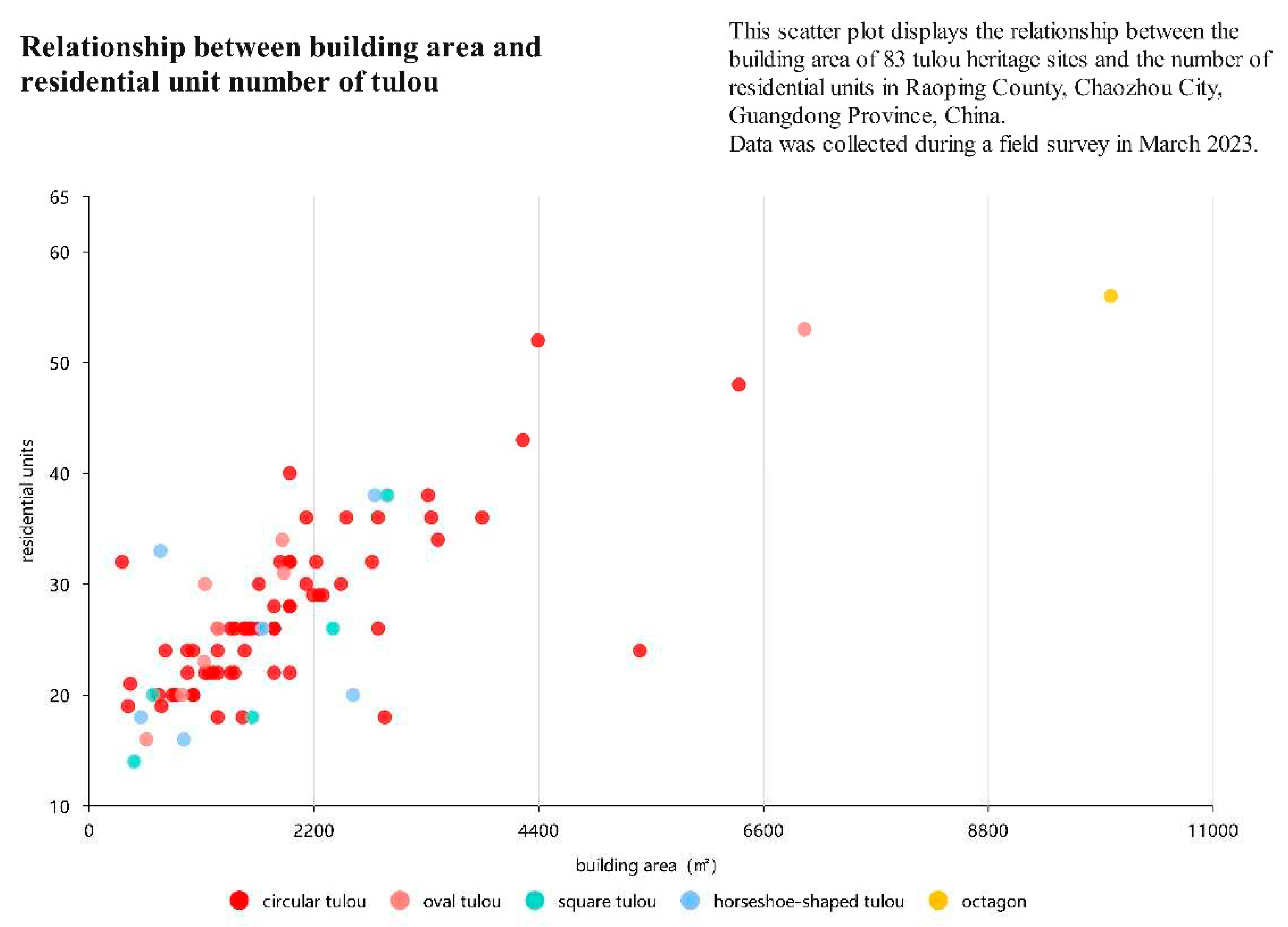

As illustrated in

Figure 12, an analysis of 83 cases revealed that circular tulou were the most common, with 63 instances accounting for 75.90% of the total. Oval tulou were the second most prevalent, with eight instances (9.64%), followed by six horseshoe-shaped tulou (7.23%), five square tulou (6.02%), and one octagonal tulou.

Circular tulou exhibit a wide range of diameters, from ten meters to several hundred meters. In terms of building area, 33 of them fall within the 1,000 to 2,000 square meter range, representing 52.3% of the total. Additionally, 12 tulou have an area between 2,000 and 3,000 square meters (19%), ten cover less than 1,000 square meters (15.9%), and eight span more than 3,000 square meters (12.7%).

The majority of circular tulou consist of 20 to 30 units, with 38 instances accounting for 60.3% of the total. There are also 16 tulou with 30 to 40 units (25.4%), five with 10 to 20 units (7.94%), and four with over 40 units (7.94%).

A comprehensive analysis of 83 Raoping tulou demonstrated that, regardless of their shape, the building area of these structures typically falls between 500 and 3,000 square meters. Furthermore, each residential unit within a tulou has an average building area of approximately 70 square meters (

Figure 13).

Figure 8.

Zilai Lou in Zhangxi town.

Figure 8.

Zilai Lou in Zhangxi town.

Figure 9.

Fuhai Lou in Shangrao town.

Figure 9.

Fuhai Lou in Shangrao town.

Figure 10.

Taihua Lou in Raoyang town.

Figure 10.

Taihua Lou in Raoyang town.

Figure 11.

Hantian Lou in Dongshan town.

Figure 11.

Hantian Lou in Dongshan town.

Figure 12.

The distribution of tulou shapes.

Figure 12.

The distribution of tulou shapes.

Figure 13.

The relationship between building area and residential unit number of tulou.

Figure 13.

The relationship between building area and residential unit number of tulou.

The circular shape of tulou has been a topic of discussion among scholars. Several theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. Some suggest that the circular shape is associated with wealth, as ancient copper coins were circular. Others argue that it represents the Chinese cultural belief in an “orbicular sky and square earth”, which is symbolized by circular tulou structures. There is also the view that the rounded shape avoids sharp angles that may create hostility towards neighbors or disrupt the surrounding environment.

The debate regarding whether tulou evolved from square to round or from round to square remains unresolved. Nevertheless, it is well-established that the primary objective of tulou was to bolster the defensive capabilities of residential buildings. As shown in

Table 1, the circular tulou, in particular, presents several advantages for defense, including a wider field of view and the absence of blind corners or areas susceptible to fire. Worth noting is that the fan-shaped design of each room within a circular tulou is in contrast to the “be horizontal and vertical” principles guiding traditional Chinese architecture. From a functional perspective, the fan-shaped design was found to have limitations in terms of its furnishing potential. After thoroughly considering the pros and cons, it was decided that the circular building design would be more suitable.

Table 1 illustrates several advantages of this design, including enhanced defense capability, structural stability, earthquake resistance, and cost-effectiveness for construction and maintenance. These critical factors ultimately contributed to the selection of the circular building design [

24].

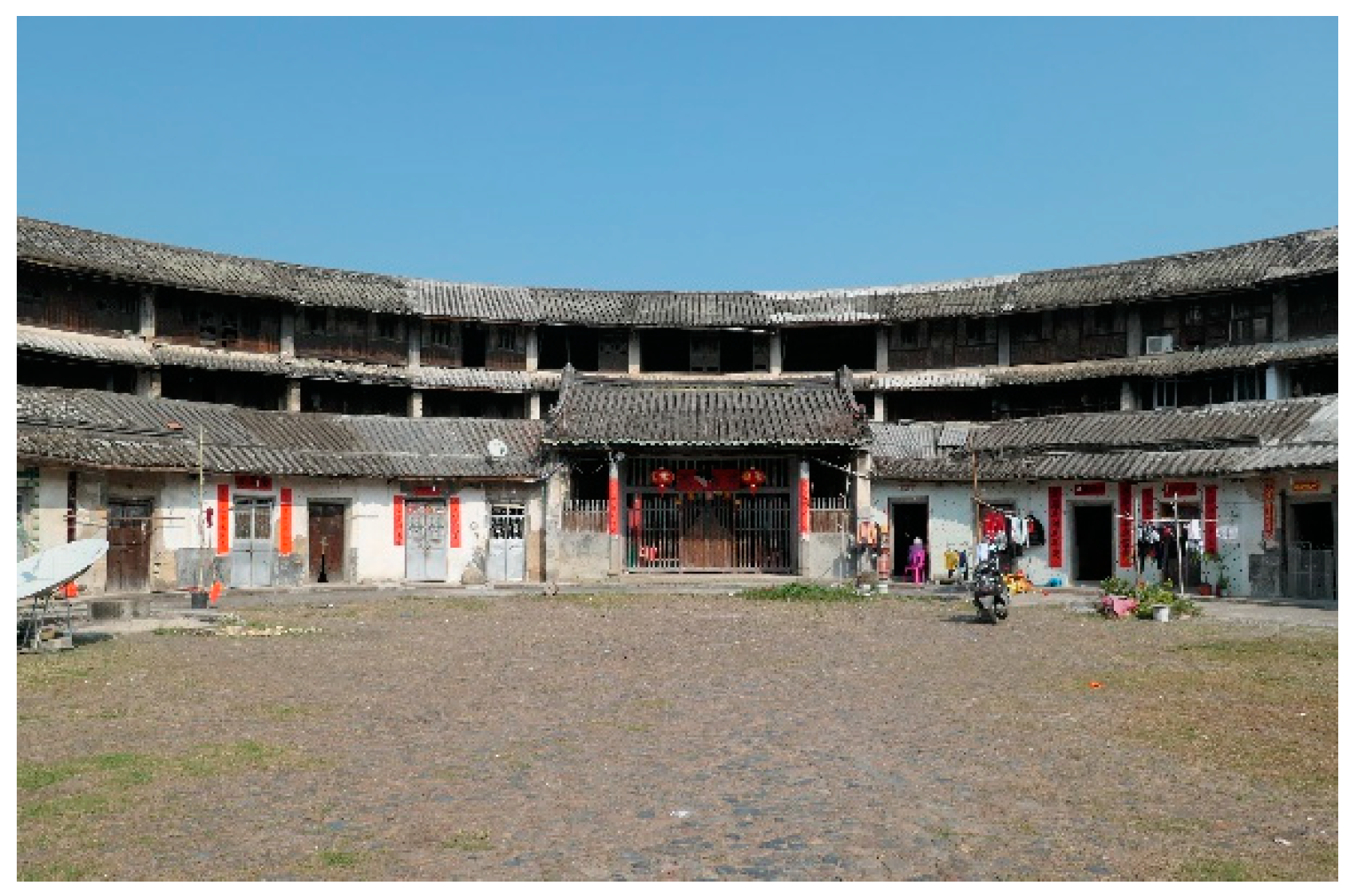

5.3. Lou Bao: outer ring building of tulou

Many Raoping tulou are accompanied by one or more outer ring of earthen buildings, known locally as “Lou Bao” (楼包), which were built mostly after the primary tulou. Loubao, like the principal tulou, feature a unit-based layout and rise 2-3 stories high (

Figure 14). Encircling the central tulou, the Loubao breaks at its primary entrance, creating an entrance square referred to as “Wai Cheng” (外埕).

The interior space of the primary tulou is highly compact, and after a few generations, it becomes too congested to support an entire family or clan. Constructing additional outer rings around the principal building has become a convenient and cost-effective strategy. Since small families may face varying circumstances when raising funds for another tulou, building units for the outer enclosure building one by one is a practical and adaptable solution. This is an essential benefit of the unit-based layout of the tulou, as it demonstrates excellent adaptability in accommodating a growing household population with high derivative performance. Lou Bao units are typically preferred by residents since they are wider than those in the main building. This creates more spacious and comfortable living spaces, even though shared amenities such as a well and large interior courtyard are available in the central building (

Figure 15).

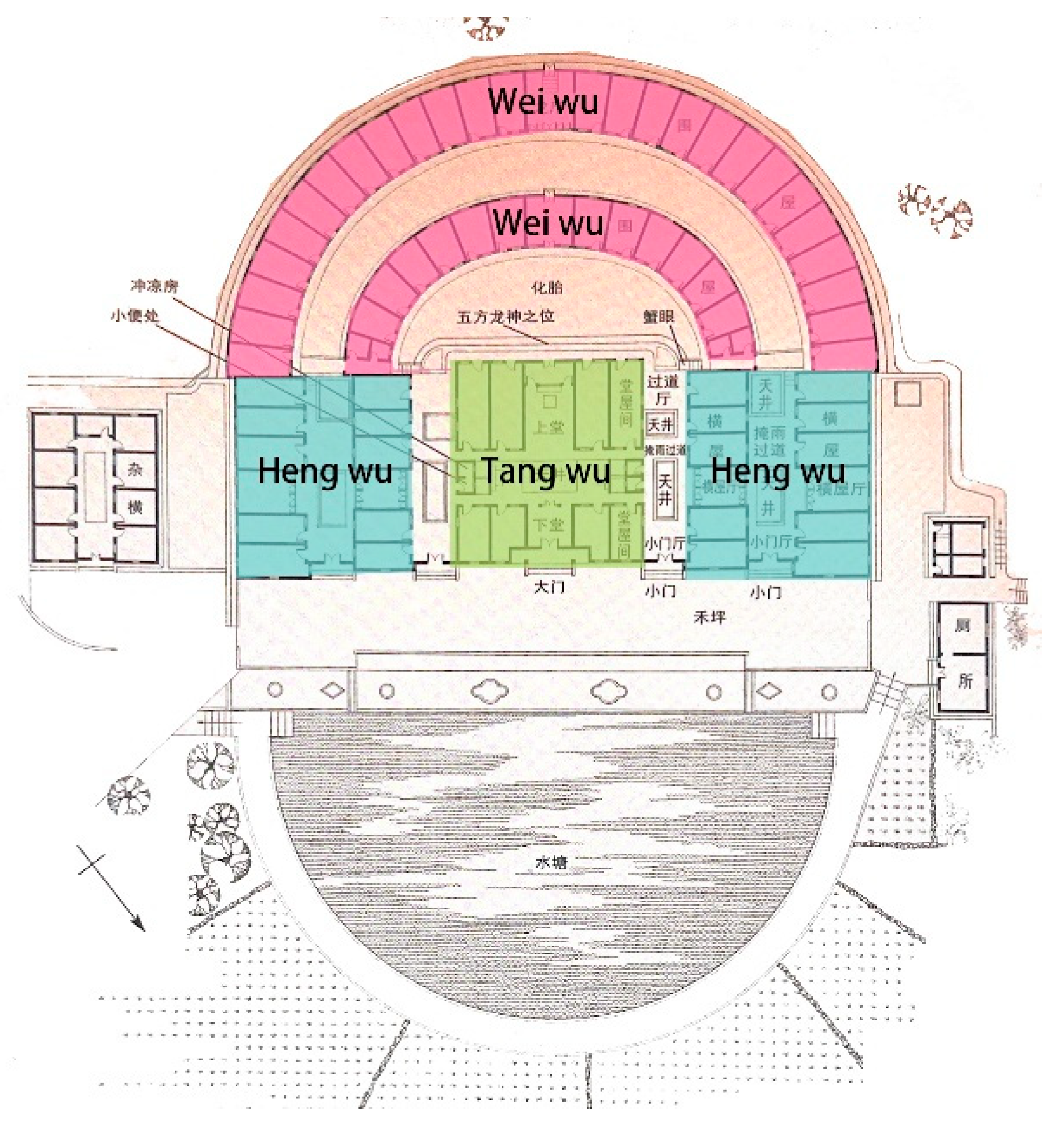

Adjacent to Raoping County, Guangdong Hakka Cultural District features a prevalent residential architecture style known as “Wei Long House”. This architectural style is characterized by a central sequence of two or three halls, flanked by row houses named “Heng Wu” on the right and left side and half-ring enclosure houses known as “Wei Wu” at the rear. The Dragon Hall, located at the center of Wei Wu, is where according to the Feng Shui theory, the mountain’s vital energy condenses. The Lou Bao buildings in Raoping tulou may have developed from “Wei Wu” and “Heng Wu” in the Hakka Wei Long House, as Lou Bao is rarely found in Fujian Hakka and Fulao tulou dwellings. (

Figure 16).

Tulou was once widely known as a fortified settlement with strong defensive capabilities. However, as Raoping Tulou developed after the mid-Qing Dynasty and political and social stability prevailed, the defensive nature of tulou began to weaken, and living conditions improved. This is demonstrated by the construction of Lou Bao buildings with added balconies, although the overall form of tulou remained largely unchanged. Some defensive features common in Ming-era tulou were viewed as unnecessary and wasteful at the time, including a continuous gallery accessible from all residential units for effective defense organization and sighting balconies. Some tulou even lacked gates, being entirely open and facing the entrance square and half-moon pond (

Figure 17).

Due to practical constraints imposed by rammed earth and adobe masonry construction materials, the placement of windows on the outer walls of tulou is still limited to the top floor. Thus, openings cannot be too numerous or large. Also, traditional Chinese residential houses follow a “closed outside, open inside” tradition. For example, the famous “Beijing Si He Yuan” (四合院, courtyard house) does not have windows on the exterior walls. The villagers noted that the windows on the top floors of the tulou were scaled to meet their needs for transporting items (such as food and firewood) upstairs on pulleys, without mentioning their suitability for shooting.

Tulou dwellings evolved from a fortress for collective defense to an intensive settlement type adapted to the challenging terrain of mountainous regions with limited arable land. Consequently, tulou gradually shifted towards enhancing openness and comfort.

Figure 14.

Yangdong Lou in Dongshan Town.

Figure 14.

Yangdong Lou in Dongshan Town.

Figure 15.

Qingyang Lou in Shangrao Town.

Figure 15.

Qingyang Lou in Shangrao Town.

Figure 16.

Hakka Weiwu (Dexin Tang of Meizhou city) [

26].

Figure 16.

Hakka Weiwu (Dexin Tang of Meizhou city) [

26].

Figure 17.

An un-gated open tulou(Bei Lou in Dongshan Town).

Figure 17.

An un-gated open tulou(Bei Lou in Dongshan Town).

5.4. Public space and facilities

The public spaces of Raoping tulou primarily consist of the entrance square, commonly known as “Waicheng” (outer square), the spacious inner courtyard referred to as “Neicheng” (inner square), and two significant units: the gate unit and the central axis unit opposite of it. The gate unit is typically used for communal storage, while the central axis unit was traditionally utilized as a family ancestral hall for clan ancestor worship or a public hall for discussing family affairs. In cases where central axis units were used as ancestral halls, specific ones were widened to indicate a higher level of ritual importance than other residential units. A few ancestral temples are independently constructed within the inner courtyard of the tulou, frequently adopting the architectural style of standard ancestral temples rather than those found within tulou. (

Figure 18,

Figure 19)

Public facilities primarily include ponds outside the gates and wells in the Neicheng. The pond serves as a firewater reserve and for fish farming. Villagers recall their past struggles with poverty when meat was rare except during Spring Festival, when families would fish from the pond and cook together, filling the tulou with delicious food and deep affection.

The central area of tulou is a communal square typically paved with pebbles or gravel. This valuable open space serves as a hub for residents to carry out daily activities such as laundering and drying clothes, processing crops, and raising poultry and livestock such as chickens, ducks, and pigs. Additionally, it serves as an ideal location for hosting ceremonies and clan feasts during festivals or ancestral worship.

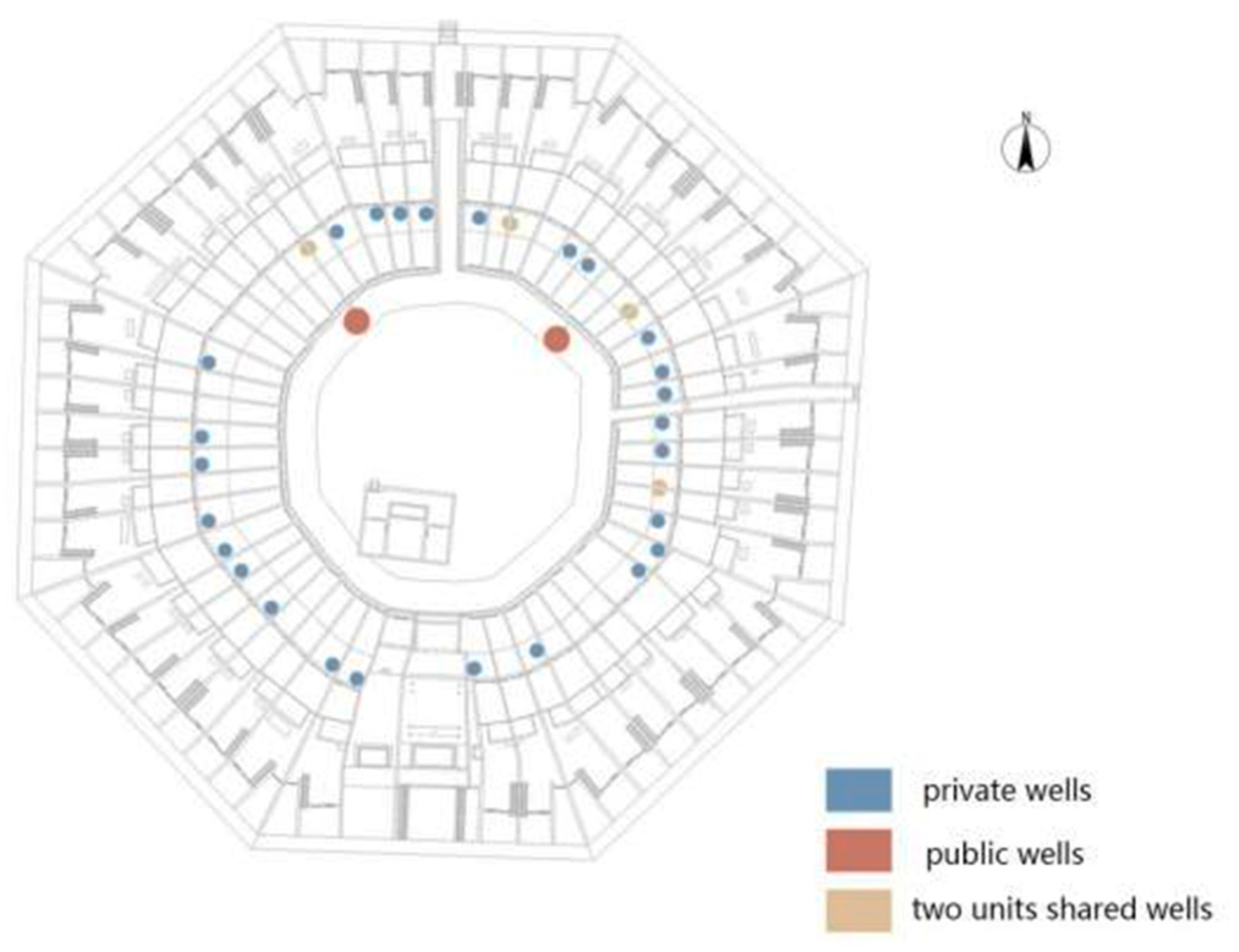

In Neicheng, shared wells are a common sight, with one or two typically found in the area. Some residences also possess private wells, such as Daoyun Lou, which houses a total of 32 wells. These wells have an average inner diameter of approximately 51 cm and an outer diameter of around 95 cm. Among the 32 wells in Daoyun Lou, two are public, while the remaining 30 are privately owned. Of these private wells, 26 are located in the front courtyards between the foyer and mid-hall of each residential unit, while four can be found under the boundary walls of two units. Constructed in 1477 during the Chenghua period of the Ming Dynasty, Daoyun Lou was built amidst widespread Japanese pirate activity and public security turmoil. The abundance of wells in Daoyun Lou ensured a plentiful water supply for both domestic use and firefighting, even during times of attack or extended closure. (

Figure 20)

Figure 18.

The ancestral hall unit located on the central axis (Wuquan Lou of Xinfeng Town).

Figure 18.

The ancestral hall unit located on the central axis (Wuquan Lou of Xinfeng Town).

Figure 19.

The ancestral hall alone in the certer of Neicheng ( in Double Luo village, Dongshan Town).

Figure 19.

The ancestral hall alone in the certer of Neicheng ( in Double Luo village, Dongshan Town).

Figure 20.

Distribution of water wells in Daoyun Lou (in Sanyao Town).

Figure 20.

Distribution of water wells in Daoyun Lou (in Sanyao Town).

6. Space layout of residential unit

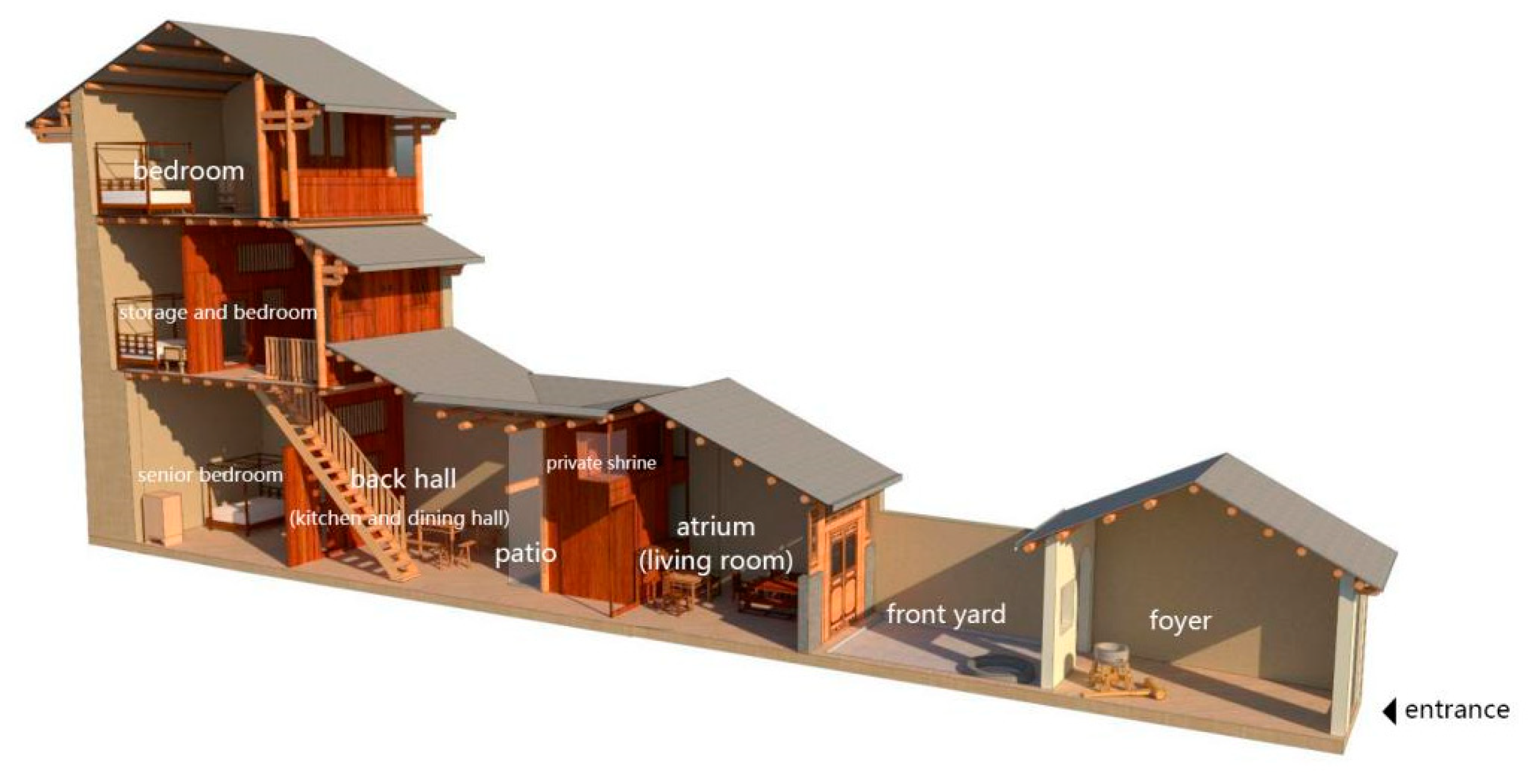

The residential units of Raoping tulou are divided by load-bearing walls made of pisé or adobe. Circumferential beams provide sufficient freedom in the depth direction by distributing the floor load from one load-bearing wall to another. Consequently, a residential unit typically encompasses a variety of domestic functions, including a foyer, living room, kitchen, dining room, storage, sleeping area, and occasionally, elevated shrines for sacrificial purposes. (

Figure 21)

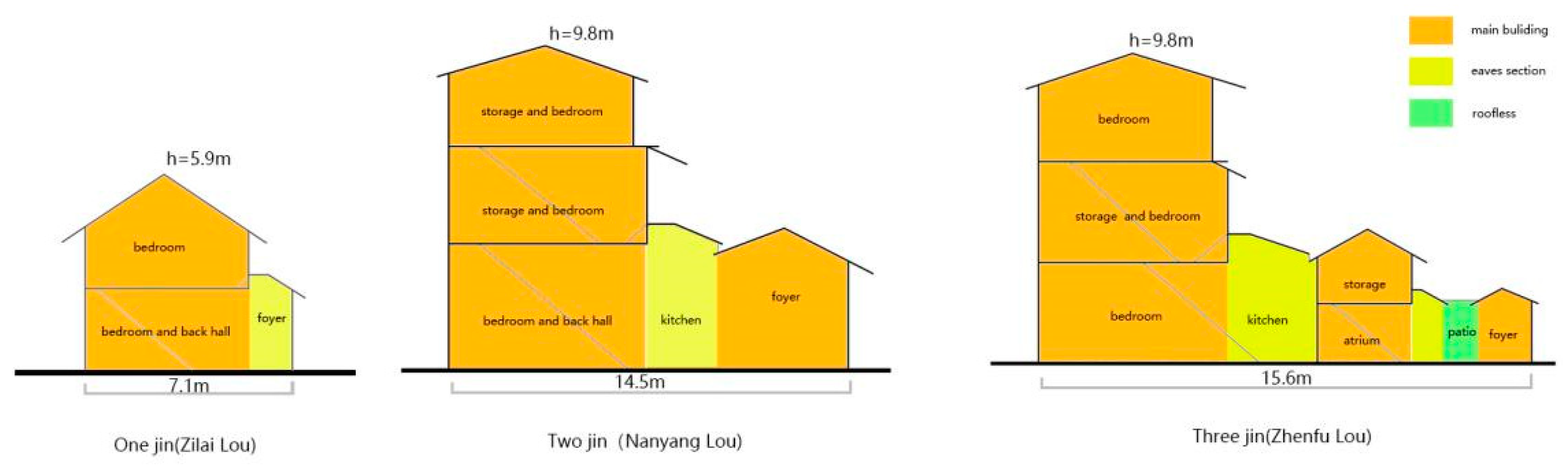

Tulou residential units can be classified into three types based on their spatial composition: one, two, and three “Jin”. “Jin” refers to a roofed space in the longitudinal direction of ancient Chinese architecture, separated from other “Jin” spaces by open areas, courtyards, or patios. The primary factor influencing the type of residential unit is the unit depth, which is determined by the size of the housing site and the available construction funds.

As the depth of living spaces increases, they become more spacious and comfortable. The most basic residential unit is the one-Jin type, consisting of a single room with a sloping eave. By extending the depth by three or four meters, a vestibule can be added, not only expanding the living area but also creating a skylight between its roof and the hall’s eaves for improved lighting. As the depth continues to increase, a small patio and sidewalk can be incorporated, with the front and rear halls opening up to the patio for enhanced ventilation and lighting. The latter two configurations belong to the two-Jin type. When the depth exceeds 12 meters, a three-Jin residential unit can be formed, containing three interior spaces separated by a private courtyard and a patio. (

Figure 22)

The primary structures of Zilai Lou, Longgang Lou, and Huanan Lou are one-Jin tulou buildings with depths ranging from 7.0 to 7.5 meters. The first floor is an open space without an inner courtyard or patio. These buildings vary in height. For example, Longgang Lou features a loft on the relatively higher ground floor, giving it a two-story exterior facade while having three stories inside, including an attic storage. As residential dwellings, individuals may also undergo spatial transformations based on their evolving living needs and household economic conditions. The sloping entrance roof of the Huanan Lou residential unit was replaced with a concrete flat roof, creating a spacious terrace and enhancing daily convenience.

Two-Jin residential units are the most common type, differentiated from one-Jin units by the addition of a single-slope eave between the front and rear halls. Some incorporate narrow patios or courtyards where depth allows, and their height ranges from two to four stories.

As living spaces expand in depth, they can accommodate a three-Jin residential unit, which features a courtyard and patio or two patios. The average depth of a three-Jin unit is nearly 15 meters, with “Daoyun Lou” having the maximum depth of 25 meters and an impressive spatial sequence: foyer - front yard - mid-hall - patio (side walk) - back hall. The front yard is so spacious that it even contains a private well. The generous depth and open spaces, including courtyards and patios, allow for ample natural light and ventilation, significantly improving the quality of life.

Generally, the interior of a residential unit consists of a foyer, kitchen, living room, and elderly bedroom on the ground floor, with storage and bedrooms on the upper floors. Residents often use the second floor for grain storage, as the first floor is damp and unsuitable for food storage. Since meals are cooked over an open fire on the first floor, the second floor is elevated and relatively dry, making it less prone to insects and mildew.

Bedrooms on the second floor and above feature a wooden “door with side lights” window, facing the spacious Neicheng. Outside this window is a small platform or corridor for drying crops. The layout of Raoping Tulou adheres to the Chinese residential tradition of a “closed exterior, open interior” concept. The only small window is located on the uppermost floors, providing ventilation and serving as a lookout and shooting hole for defense purposes. Additionally, fixed pulleys are installed to transport goods upstairs for storage. (

Figure 23)

Figure 21.

Space layout of a residential unit of Daoyun Lou in Sanrao Town.

Figure 21.

Space layout of a residential unit of Daoyun Lou in Sanrao Town.

Figure 22.

Space layout of residential units at varying depths.

Figure 22.

Space layout of residential units at varying depths.

Figure 23.

The wooden “door with side lights” window on the second floor and above (Chaoyuan Lou of Shangrao Town).

Figure 23.

The wooden “door with side lights” window on the second floor and above (Chaoyuan Lou of Shangrao Town).

7. Conclusion

Raoping tulou showcase a distinct local character, addressing both the physical and spiritual needs of its communities. It holds significant heritage value as an exemplary piece of residential architecture in South China and a remarkable example of earth architecture worldwide [

27]. Initially, the unique shape of the building attracted attention, but in recent years, its design ingenuity as a vernacular dwelling constructed and inhabited collectively, along with its ecological construction technology utilizing local resources such as earth, cobblestone, and timber with minimal energy expenditure while harmonizing with the surrounding landscape, has gained increasing recognition. However, with the advancement of the economy and industrialization, tulou have experienced a significant decline due to abandonment, improper reinforcement, spatial transformation, material replacement, and other factors. The local government has actively implemented various strategies for the sustainable development of tulou, aiming to safeguard the architectural heritage and its associated value cognition while simultaneously meeting the living needs of individuals to the greatest extent possible.

Commissioned by the Raoping County government of Chaozhou City, the team conducted a comprehensive investigation on Raoping Tulou. Firstly, this paper carries out a comprehensive analysis of historical documents and local chronicles to reconstruct the historical scenes. It systematically reveals the emergence, popularity, and consolidation process of tulou dwellings as integrated defensive and residential buildings for ordinary people, under the combined pressures of Japanese pirates and bandits, as well as the local government's call for “small village merge into big ones”, “build fortresses”, and “train villagers”.

Secondly, through analyzing geographic information, this paper summarizes the distribution features of Chaozhou tulou along the Huanggang River and its tributaries. Additionally, it reveals the underlying reasons for the absence of tulou dwellings within 50 miles of the coast by examining both the “Maritime Trade Ban” and “Coastal Evacuation Decree” issued during the Qing Dynasty.

Thirdly, Raoping County is home to both Hakka and Fulao people, with the former residing in the north and the latter in the south. However, a comprehensive analysis of Raoping Tulou and its residential units reveals no fundamental differences between these two ethnic groups in terms of dwelling types and spatial layouts. Ethnic cultural characteristics are primarily reflected in architectural decorations and non-load-bearing wooden components, such as doors, windows, and railings. In fact, variations in scale, spatial layout, materials, and construction techniques of tulou are often determined by economic factors (building funds, land areas, and geographical locations, etc.). This highlights the adaptability and flexibility of traditional residential structures.

Furthermore, the Loubao building in Raoping Tulou is a rare example within Fujian Tulou, likely influenced by the “Wei Long Wu”, the predominant Hakka residence style found to the north of Raoping, and evolved from part of its “Wei Wu” and “Heng Wu”. This emphasizes the inclusive nature of traditional dwellings.

Fourthly, it is important to note that tulou residential buildings are not static, although few studies have mentioned this. Tulou constructed during the Ming Dynasty placed a greater emphasis on defense, featuring higher and thicker rammed earth walls, high-quality hardwood, and iron-clad doors measuring 10-15 cm in thickness, as well as corridors built on the top floor to connect living units for coordinated defense.

By the mid-Qing Dynasty, with the recovery of Taiwan and improved domestic security, the defensive nature of tulou gradually diminished. Instead, people focused on enhancing their living conditions through various creative means, such as constructing wider and more convenient residential units on the outer circle of the original tulou rather than building new ones. Some tulou were built without gates, allowing the entrance square to connect with the inner square. Today, field investigations reveal that it is common for residential units to install separate doors and windows on the rammed earth exterior walls of tulou to improve lighting and ventilation. This demonstrates the potential for development and residents’ initiative in traditional residential architecture. People will always actively modify their homes to meet their growing spiritual and material needs, in accordance with their financial capabilities. This not only presents an intriguing aspect of residential architecture but also poses an inevitable challenge in preserving the heritage of residential architecture.

In the future, on the one and, we plan to systematically analyze the architectural characteristics and construction technologies of Raoping Tulou. Our goal is to inherit the wisdom passed down from generation to generation and explore its potential in realizing ecological harmony and sustainable development of architecture. We also aim to rethink the modern application of this ancient construction technique for future development.

On the other hand, we aim to thoroughly examine and summarize the preservation status and damage mechanism of Raoping Tulou. This will enable us to fully tap into their potential for multiple functions for the original function currently cannot comprehensively support people’s higher quality of life and lead to an increase in rebuilding and renovation [

28]. In the current social context, actively exploring the protection and inheritance mechanisms of tulou is an extremely critical and urgent task. Simultaneously, we must endeavor to re-establish a strong connection between the tulou heritage and contemporary communities in order to transform it from being solely a relic of the elderly into a collective memory for all.

Notes on contributors: Dan Chen is a lecturer in the Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Urban planning at Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, and a visiting scholar at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, TU Delft, the Netherlands. Her research focuses on the evaluation of value, restoration, revitalization, and conservation planning of architectural heritage. Jian-ping Ye is a lecturer in Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Urban planning at Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China. His research interests include vernacular culture, open-form architectural theory, revitalization and conservation planning of built heritage in South China.

CRediT authorship contribution statement: Dan Chen: Fieldwork, Methodology, Research and analysis, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review& editing. Jia-ying Su: Fieldwork, Research and analysis. Jian-ping Ye: Fieldwork, Research and analysis, Project administration.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52108007); Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. GD21YYS04); Basic Research Planning Project of Guangzhou City (No. 2023A04J0981).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the editors of this journal for a rigorous process and significant contribution of the anonymous reviewers which have produced a better article.

Declaration of interest statement: No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bernardo, G., Guida, A., Pacente, G. (2022). The sustainability of raw earth: an ancient technology to be rediscovered. Journal of Architectural Conservation. Vol(28), 89-101. [CrossRef]

- Needham, J. Science and Civilisation in China.Volume I, Introduction, Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990.

- Qin, Q., Xiao, D., Ma, J., Tao, J. (2021). Using graphic comparison to explore the dynamic relationship between social conflicts and Fujian Defense-Dwellings in China. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering. Vol(21), 2285-2305. [CrossRef]

- Porretta, P., Pallottino, E., Colafranceschi, E. (2022). Minnan and Hakka Tulou. Functional, Typological and Construction Features of the Rammed Earth Dwellings of Fujian (China). International Journal of Architectural Heritage. Vol(16), 899-922. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R. G. 2000. China’s old dwellings. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press:223.

- Zhou, H., and S. Dong. 2015. Impact of ethnic migration on the form of settlement: A case study of Tulou of South Fujian and the Hakkas. Journal of Landscape Research 7:75–78.

- Xu,W.; Yang, C.; Li, J. The Regeneration Path of Historical Buildings and Environment under the Concept of Community Building: Taking Fujian Qingpu TulouCultural Center as an Example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 74–79.

- Fernando Vegas, Camilla Mileto, Alicia Hueto Escobar & María Lidón de Miguel (2022) Sustainability, Risks and Resilience of Vernacular Architecture, International Journal of Architectural Heritage, 16:6, 817-819. [CrossRef]

- Pan Ying, Ed. Chaoshan Folk Houses(潮州民居) [M]. Guangzhou: South China University of Technology Press.2013:157.

- Zheng Jing, an associate professor in the Department of Architecture at Wuhan University, public lecture. Check out the details here: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Px493kFcVjFOCEDdCx913Q.

- Taizu Records of Ming, Vol 70, 139, 159, Taiwan, School of History and Language, Taipei Academy of Central Studies, 1962.

- Taizu Records of Ming Dynasty, Taiwan, School of History and Language, Taipei Academy of Central Studies, 1962:205.

- More details see: (Ming)·edited by Chen Tianzi. DongLi Zhi ( Annals of Dongli Peninsula). [M] Chaozhou: Xiangqiao Wenxing Printing Factory. 2001.

- (Ming)·edited by Chen Tianzi. DongLi Zhi ( Annals of Dongli Peninsula). [M] Chaozhou: Xiangqiao Wenxing Printing Factory. 2001: 53.

- 陈贤波[Chen Xianbo], 重门之御——明代广东海防体制的转变[The Emperor of the Heavy Gate - The Transformation of the Guangdong Coastal Defense System in Ming Dynasty], Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2017.123.

- 塘湖刘公御倭保障碑记 [Tanghu Liu Gongyu Wobao Stele Inscription], edited by Chen Liming [陈历明]. History of Chaoshan Cultural Relics (Part 1)(潮汕文物志 上). 1985. Shantou Cultural Relics Administration Committee Office, 335. Vol. I.

- (Ming) 张萱[Zhang Xuan]. 2018. 西园闻见录[Xi Yuan Wen Jian Lu], 3129. Vol. 98. printed by Harvard Yanjing Xueshe.

- 郑振满[Zheng Zhenman]. 2009. 乡族与国家—多元视野中的闽台传统社会[The village and the country: The traditional society of Fujian and Taiwan in a multi perspective]. Beijing: Sanlian bookstore.

- Freedman, M. 1958. Lineage Organization in Southeastern China. London: Athlone Press.

- 陈春声[Chen Chunsheng]. 2001. “从“倭乱”到“迁海”——明末清初潮州地方动乱与乡村社会变迁[From “Japanese pirates rebellion” to “moving off the sea” – Local unrest and rural social changes in Chaozhou at the end of Ming and early Qing]”. 明清论丛[Treatises of Ming and Qing Dynasty]. (Vol. 2, 96). Beijing: Forbidden City Press.

- Huang, H. 2009. Fujian Tulou, treasures of traditional Chinese dwellings. Trans. Y. Yang. Bejiing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. in part chap. 4.

- 黄汉民 [Huang Hanmin].福建土楼:中国传统民居的瑰宝(修订版) [Fujian Tulou: A Treasure of China’s Traditional Dwellings (Revised Edition)].Life-Reading-New Knowledge Sanlian Bookstore.2017:261.

- Zheng, G., J. He, D. Hu, Y. Lin, W. Jian, and H. Chang. 2008. Fujian Tulou. Paris: Print. Rep. no. 1113:4.

- 李雄飞 [Li Xiongfei].国之瑰宝——二宜楼和华安大地土楼群 [National Treasure: Eryi Lou and Hua’an Earth Building Group][J] Huazhong Architecture.2007(9):141-150.

- Shen, Y.L.; Yan, X.C.; Yu, P.Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.F.; He, W. Seismic resistance of timber frames with mud and stone infill walls in a chinese traditional village dwelling. Buildings 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- 陈志华[Chen Zhihua], 李秋香[Li Qiuxiang].梅县三村.[Mei Xian San Cun]. Tsinghua University Press.2007:114.

- Frangedaki, E., Gao, X., Lagaros, N. D., Briseghella, B., Marano, G. C., Sargentis, G. F., Meimaroglou, N. (2020). Fujian Tulou Rammed Earth Structures: Optimizing Restoration Techniques Through Participatory Design and Collective Practices. Procedia Manufacturing. Vol(44), 92-99. [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.W.M.; Zhang, F.; Ho, J.K.C. Effectiveness and advancements of heritage revitalizations on community planning: Case studies in hong kong. Buildings 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The Fulao, a sub-group of the Han ethnic group, originated from the central plains of the Yellow River in northern China and mainly reside in Minnan (southern Fujian) and Chaozhou (eastern Guangdong) areas. The Fulao and Hakka ethnic sub-groups, to whom Tulou dwellings are attributed, migrated to this region via two distinct routes: the Minnan arrived from the southern coast and settled at the estuary of major waterways; whereas, the Hakka crossed over Wuyi Mountains and established themselves along river valleys. (for further information regarding the migration history of these two ethnic sub-groups, please refer to: Knapp 2000, 223; Zhou and Dong 2015) |

| 2 |

Despite their generic uniformity, Chinese tulou can be roughly divided into two groups: Minnan and Hakka tulou. These were built by the Minnan and Hakka populations respectively, reflecting their different ways of life and ideas about living, corresponding to the unit layout and the circular corridor layout. |

| 3 |

Hakka residential buildings in different historical periods and different regions have different changes, including Tulou, Weilou, Diaolou, etc., while the most representative one is the Weilongwu in Meizhou, Guangdong Province. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).